1. Introduction

Tax imposition and collection is a subject which will always resonate across the citizens of the Slovak Republic from the point of view of fulfilling social security and ensuring social protection. The awareness that the citizens will be secure in terms of social justice in the country, which through its bodies, institutions, policy, and its instruments, plays a part in the creation of the social environment focused on the satisfaction of social rights guaranteed by the Constitution of the Slovak Republic, should be the attendant symptom of tax collection. Even in a democratic society with comprehensive legal guarantees and security, we cannot safely say that the application and promotion of certain ideas, principles, and intentions is always correct throughout the society. It is relevant to add the opinion of the authors

Terell and Gilbert (

2012), who declare that ‘the model itself as well as the mechanisms of the country’s policy objectives depend mainly on a political regime’. The distribution of income lies at the intersection of states and markets, both influencing and responding to government policy (

Kogan 2017).

The aim of this paper is to emphasize the causal nexus and the dependency of tax policy and the tax system on the social status of economically active subjects, to stress the necessity of the consideration of social function when imposing and collecting taxes from the point of view of the regulation of legal adjustment of the Slovak Republic. We focus on the institution of the minimum wage, which represents the basic guaranteed wage right of the employee and has to provide him/her with a minimal standard of life at a certain, socially acceptable level. The minimum wage has to provide him/her with this living standard even after tax deduction. If we consider the minimum wage as an economically successful social tool, which has the function to maintain the living standard of low-paid employees, then we have to distinguish it from the subsistence minimum, which is not considered to be an economic success from the point of view of the state.

The tax system in the Slovak Republic, like in any member state of the European Union, was shaped by the action of many influences, especially political, economic, and social ones. In this context, it is necessary to perceive the level, dynamics, and especially the internal construction of the tax system in continuity with the priorities set out by the ‘actual’ government, since almost all political parties deal with the problems of the ‘tax system’, but each of them interprets the tax system in a different way from the perspective of the party’s values, and they promote the solutions in a different way in their programs and within a different time horizon. It should not be in accordance with the position of the state as a social state to perceive the tax law without regard to the social status of the country’s inhabitants.

Beblavý (

2009) declares that ‘the sociological view on the tax imposition and collection is the opposite of the economic one, since it says that people are influenced especially by their family and the closest persons and therefore they do not consider a motivation to be the main aspect’. We point out this social aspect of tax policy in our paper. The constitutional and political system of the Slovak Republic is based on the principles of the rule of law (

Horváth 2017). In this context, any decisions, measures, and legislative changes being adopted in the sphere of taxes must be in accordance with the social security and social safety of the inhabitants. The legal environment depends on the legislation, which establishes the rules for competition in the market. The public policy is generally more responsive to the preferences of the rich (

Oh 2017). Legislative processes that are not suitably set could be counterproductive for the society. It should also not be an administrative burden (

Jovanović and Klun 2017).

2. Literature Review

One of the fundamental social rights applied in a work process is undoubtedly the right to work, which according to

Tomandl (

1994), we can perceive as the right (a) to a paid job, (b) to sufficient employment policy from the part of the state, (c) to social security in the case of unemployment.

When trying to define selected social policy instruments in relation to tax policy, it is necessary to deal with the results of relevant studies addressing, for example, the motivating function of the minimal wage, as is pointed out by

Pavelka et al. (

2014), and also with the conditions of minimum wage indexation defined by

Pernica (

2016), the total impact of the minimum wage (

Fabo and Belli 2017;

Lenhart 2017;

Ondruš et al. 2017;

Uhrová and Skalka 2016;

Macková 2008), and the effect of the minimum wage on employment (

Dolado et al. 1996;

Bruun et al. 2017) and on reducing poverty (

Jurčíková 2008;

Kogan 2017). It is necessary to define the significance of taxes, as

Molitoris (

2008) states; the social function of taxes are pointed out by

Králik et al. (

2001); the employee bonus, with its social but also stimulatory function, is defined by

Králik and Jakubovič (

2004); it is also important to understand the aspect of minimum living standards (

Fabo and Belli 2017) and its relationship to the subsistence minimum (

Rievajová 2006).

Batrancea and Nichita (

2012) define tax compliance models as a means for ensuring the fulfilment of the state’s functions and sufficient sources for activities in the public sector.

However, first and foremost, for this study, it is essential to define the social policy and the social status of individuals, as

Muller (

1991),

Krebs (

2005),

Barinková (

2007),

Beblavý (

2009),

Žofčinová (

2010),

Terell and Gilbert (

2012),

Mihalik (

2015), and

Horváthová (

2016) have done.

The knowledge of the legal quality of these rights also considerably influences their actual utilization in social practice, being fully aware of their conditionality according to the material and living conditions of the society. Today, in the context of globalization, the economic and political power of a modern state increases and its social functions are considerably widening. The increasing state intervention in all the spheres of public life is supplemented by an active intervention into social relations, as well as the regulation of connections between working activities and the capital itself for the given enterprise and subject (

Horváthová 2016). The economic determination is clearly evident in Act 35 of the Constitution of the Slovak Republic, where the right to work is declared. However, it does not include the duty of the state to employ every citizen, but within the economic policy of the state, the state is to make efforts to create the environment for employment opportunities. The right to work is stated in Art. 35 par. 3 of the Constitution of the Slovak Republic, according to which, ‘the state shall materially and to an appropriate extent provide for citizens who are unable to exercise this right through no fault of their own’. Opinions regarding the determination of the right to work differ in the scientific community (

Bruun et al. 2017). Two theoretical extreme positions border the relatively wide spectrum of opinions on the definition of the right to work. The first one is based on the understanding of the right to work as a legal entitlement of a citizen to the creation of a job position by the state. The understanding of the right to work as a political and legal program principle or the expression of the state’s duty in relation to the active policy of employment is its counterpart (

Žofčinová 2010).

The right to work can be seen just as a subsidiary right, which the state is obliged to ensure only on the conditions that a citizen is unemployed, he/she is searching for a job, and at the same time, is able to work. This legal concept is also the basis of the legal construction of the right to be employed in the Slovak Act on Employment Services.

1The right to work places an obligation on the state to apply an active employment policy within which it creates the elementary prerequisites of the economic security of their citizens. Therefore, the right to work remains one of the most important rights in the complex of social rights, even after change in political and economic conditions (

Katz 2018).

Barancová (

2012) considers ‘the right to payment for work that has been done to be a property/reward aspect of the labor–law relation at the level of a scientific abstraction, which should reflect the rate of work consumption and, at the same time, the appraisal rate of an individual’s work results’.

The real implementation of the right to work is significant on two levels:

The employees within the European legal space are granted the right to an appropriate remuneration for the work that has been done, so that even the lowest value of that remuneration is sufficient to ensure them and their families a dignified standard of living. Most of the European Union’s Member States, including the Slovak Republic, implements the right to the minimum wage (

Barancová 2012).

3. Minimum Wage

A minimum wage has its adversaries as well as faithful supporters in the Slovak Republic, as well as in the European Union. It has often been argued that the minimum wage has a negative impact on employment rate, because when the minimum wage is too high, it may result in the layoff of employees with low skills. However, its supporters highlight its social function and improvement of the working positions and securities of employees, since as

Macková (

2008) says, ‘the significant difference between the amount of minimum wage and social benefits is undoubtedly the important motivating factor at reducing unemployment’. The motivating function of the minimum wage is pointed out in the work of

Pavelka et al. (

2014).

Approximately 4% of people in Slovakia are working for minimum wages. The minimum wage for 2018 is 480 EUR, meaning that the hourly rate is 2.759 EUR. The minimum wage relates to the employees obtaining a monthly wage (

Pernica 2016). In 2017, the minimum wage was at the level of 435 EUR and the minimum hourly rate was 2.50 EUR. There is the obligation to pay tax and other deductions from this wage, and the amount of minimum wage less the tax and deductions is approximately 403 EUR. The minimum wage is subjected to taxation, and therefore it affects the living standards of those economically actively employed people who work for minimum wage. The lowest possible monthly wage is different in various countries. The highest minimum wage in the European Union is in Luxembourg, and the lowest one is in Bulgaria. Some countries do not implement the minimum wage. We can see in

Table 1 that the Slovak Republic is lagging behind the minimum wages paid in advanced countries. The minimum wage is also regularly increased in Slovakia. For example, in 2017, it amounted to 435 EUR; in 2018, 480 EUR; and in 2019, it is expected to be 520 EUR.

The minimum wage amount has also been a much-debated topic across the whole political spectrum in the past. The minimum wage is considered a form of social protection of employees as well as an economic motivation to enter the labor market and be employed instead of being dependent on social benefits (

Uhrová and Skalka 2016). From the point of view of employees, the minimum wage presents the basic guaranteed wage right of an employee, which has to provide him/her with a minimal standard of life at a certain, socially acceptable level and maintain his/her living standards. A high minimum wage is believed to lead to an increase in unemployment.

If, on the contrary, the lowest possible wage is set too low, there is a risk of a decrease in the standard of living of the population. This can mean that economically active people who work only for the minimum wage, which is subjected to taxation, cannot be provided with an adequate regeneration of the workforce, health care, and so forth. The minimum wage can also affect health.

Lenhart (

2017) studied the relationship between minimum wages and several measures of population health by analyzing data from 24 OECD countries for a time period of 31 years. He emphasized that the minimum wage can also affect health, and apart from this, a higher minimum wage can even decrease the mortality rate of economically active people. The minimum wage can, to a certain level, provide stability, strengthen the relationship of employees towards their work, support the growth of productivity, and help to reduce poverty (

Jurčíková 2008). The effect of the minimum wage on employment in Europe is analyzed in the work of

Dolado et al. (

1996); this study indicates the positive influence of the minimum wage on the reduction of poverty, as well in combination with tax tools that increase net income, and destroys the myth that these tools could efficiently replace the fight against poverty with the minimum wage. Another study points toward an important positive influence of wage increase (that fuels the increase of the minimum wage as well) on economic growth (

Ondruš et al. 2017).

In this setting, it is necessary and important to find an appropriate compromise. It is a gesture of responsibility for the social status of people who satisfy their living needs by working. The minimum wage is one of the measures of economic policy which raises contradictory reactions (

Pavelka et al. 2014). Within the regulations of the Slovak Republic, discussions occur about the actual valid mechanism of the establishment of a minimum wage. These discussions lead to a cancellation of this category or to amendments of an actual mechanism that establishes the minimum wage. The minimum wage increases almost every year. In the past, there have also been years of stagnation, when the minimum wage remained at the same level.

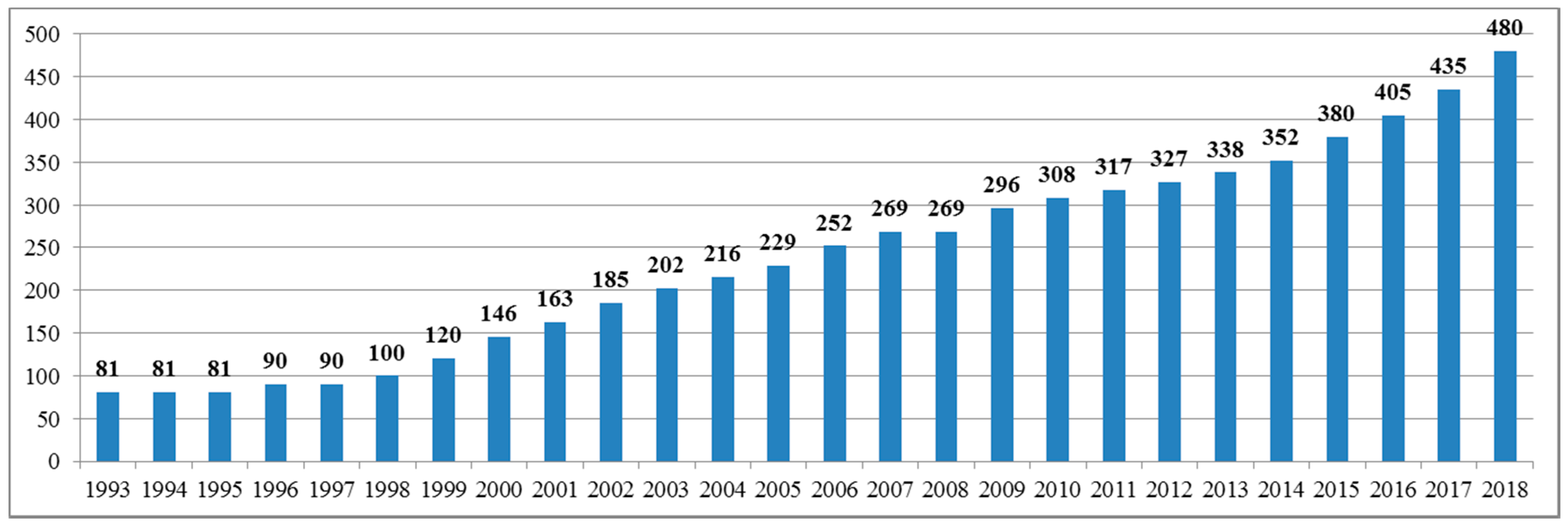

Figure 1 shows the historical overview of the minimum wage in Slovakia. The amounts given in

Figure 1 present the gross income.

Table 2 presents an overview of the European Union countries with the minimum wage implemented.

Bílý and Horváthová (

2016) consider that ‘the collection of international statistical and other relevant empirical information is a special methodological concern’. The minimum wage is not implemented in Finland, Austria, Denmark, Italy, Malta, Cyprus, or Switzerland. The most advanced countries, with the highest minimum wage in 2017, include Luxembourg, Ireland, Holland, Belgium, Germany, and France. The Slovak Republic belongs to the countries which are lagging behind more.

As shown in

Table 2, the Slovak Republic belongs to the group in which the national monthly minimum wages in January 2017 were lower than 500 EUR. This group also includes the following Member States of the European Union: Bulgaria, Romania, Latvia, Lithuania, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Croatia, Slovakia, Poland, and Estonia. Their national minimum wages range between 235 EUR in Bulgaria to 470 EUR in Estonia. It is obvious that the Slovak Republic, in the context of the minimum wage amount, is not able to compete with the advanced countries of the European Union.

4. Social Aspects of the Imposition of Tax

Under the conditions of modern European countries, a new crystallization of tax functions emerges, some of the taxes lose their actual significance to a greater or lesser extent, or they may even become extinct; and other functions of taxes are obtaining a new context and their significance is considerably increasing, as

Molitoris (

2008) states.

The social function of tax belongs to the functions being discussed. Is the “social aspect” of the imposition of tax obsolete, or does it still resonate with the public? The experts in the tax law sphere tend towards the statement that the social function of tax was until recently a typical function, but it is necessary to consider it to be obsolete nowadays, since it is not necessary to handle the social issues solely with taxes, and the influence of taxes, as a tool of social policy, should not be intense within the market economics. As a result of this, they question the existence of a social function of taxes and consider its influence to be disputable. They state that it was applied in tax construction in the past, and as a result, it was possible to transfer the tax burden of the subjects of the tax law relations according to the social position of an individual in the society and family (e.g., according to a family background) (

Králik et al. 2001).

We cannot unequivocally agree with this statement, considering the connections between the social and legal positions of individuals and the setting of the tax system. The regulation of taxes, either in the period up until the tax reform in the Slovak Republic or in the present day, provides examples regarding the social aspects on the part of a taxpayer. The reform of the tax system in Slovakia is part of a complex reform of taxes and levies in the Slovak Republic. The tax reform was supposed to contribute to public finance improvement, but its progress is accompanied by many problems and opposition from the professional public (

Jakubek et al. 2016).

Babčák (

2008), as a critic of the social function of tax, admits in his work that ‘the defined income that creates the income tax subject is tax-free, by, among other things, social reasons’. The example of a correlational relation between the tax system and social security of citizens, as a demonstration of the social function of tax, is documented by the provision of Article 9 par. 2, letter aof Act No. 595/2003 Coll. on Income Tax, as amended by later regulations (hereinafter referred to as the “Act on Income Tax”). It stipulates that the benefits and contributions for ensuring basic living conditions and for handling material needs, social services, cash contributions for the compensation of social consequences of severe disability, cash contributions for care, and so forth. The state budget is the source of the benefits to provide for material needs and support for families with dependent children.

Another argument that supports the statement that taxes perform a social function is the fact that various measures taken by a lawmaker in the sphere of taxation for the benefit of a citizen are important for the determination of social behavior and present the effort made for the improvement of certain aspects of their life. For example, when the nontaxable part of a natural person’s income tax base, which is generally used in the construction of this tax, is based on a subsistence minimum reflecting its real value, it fulfils this social function along with other deductible items from the tax base. In general, it is recognized in economic theory that the deductible items are the alternative to the direct provision of governmental allowances, that is, these are clearly the items with a social nature.

Another actual tool of the tax policy in the Slovak Republic with a social aspect is the introduction of tax credit, which means a tax advantage is granted for each dependent child living with the taxpayer in a household. It means the acceptance of the social aspects of a taxpayer, which according to the provision of Article 33 of the Act on Income Tax, is entitled to deduct (apply) the amount determined for each dependent child living with him/her in a household from the tax calculated. The total annual amount of the tax credit for 2017 was 256.92 EUR (12 months × 21.41 EUR).

The employee bonus is also non-negligible, and unlike the tax credit, it is connected only with a tax-paying person, or employee. It has no connection to dependent persons, but requires that the employee received income from an employment for a minimum period (six months) of a minimum amount (at least equivalent to six payments of the minimum wage), did not receive other defined income, and was not a recipient of pensions. The legal conditions for giving rise to the employee bonus undoubtedly fulfil not only a social, but also a stimulatory function, which according to

Králik and Jakubovič (

2004), ‘stimulates the subjects to certain behavior in the social and economic relations’. We believe that, in this case, there is a fusing of the two functions. The possibility of obtaining an employee bonus encourages the individual to accept low-paid work. It documents his/her effort to be active, to be employed, and not to be dependent on welfare benefits (e.g., the benefits providing for material need).

Both tools in the tax system mentioned above—the tax credit and employee bonus—motivate the taxpayer to make every effort to obtain their income from paid employment or from other activities, the taxation of which is set according to his/her personal and family relations. Based on the examples given above, we may state that the construction of some taxes within the tax system and their collection is clearly also affected by the social aspects, since they significantly contribute to the shaping of the social position of the subjects of social policy (individuals or social groups). However, the social aspects, even despite the disputable opinions regarding their implementation in the legal regulation of the natural person’s income taxation under the conditions of the market economy, are not only of a material and legal nature. We can see their several impacts in tax procedural law provisions. The issue is more about the social aspects of tax policy (

Žofčinová 2010).

5. The Subsistence Minimum and Tax Policy in the Slovak Legal System

We deal with the institution of the minimum wage, which is one of the most debated issues in the policy area. The debate on the minimum wage is highly polarized. In this regard, we not only focus on the legal steps of the legislator in the field of tax policy, but also in the field of the subsistence minimum. The subsistence minimum, at the same time, is the tool of social policy of the state. With regard to the undergoing discussions on the Social Pillar of the European integration, we aim to extend the debate to include the aspect of minimum living standards (

Fabo and Belli 2017). The level of the subsistence minimum determines the degree of tax burden of economically active taxpayers, and it can put the Slovak tax system into a dumping position against tax systems in other European countries.

Pursuant to Act No. 601/2003 Coll. on the subsistence minimum, the subsistence minimum is defined as a socially recognized minimum income of a natural person, below which a status of material need occurs. Historically, this term was developed within the Czechoslovak Federal Act No. 463/1991 and expressed as the “socially recognized minimum income of a citizen, below which the status of his/her material need occurs”. This meant that for the first time in Czechoslovakia, a citizen was given a guarantee that his/her social situation is an object of interest of the state’s social policy. The adoption of the Act on the subsistence minimum was preceded by the adoption of the constitutional Act No. 23/1991 Coll., which introduced the Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms, Article 30 of which stipulates the right of citizens who suffer from material need to such assistance as is necessary to ensure their basic living standard. According to

Rievajová (

2006), ‘the subsistence minimum means, in the broadest sense, a summary of goods and services, which makes the basic consumption unit to be able to satisfy the needs on a scale recognized by the society in the given period of time as minimum necessary for maintaining of the average consumption level and inclusion into the common society life’.

Thus, the subsistence minimum is to be understood as a certain boundary of income, below which a citizen is considered to be experiencing material need, according to Act No. 599/2003 Coll. About Assistance in Material Need, the purpose of which is to ensure the basic living conditions for a citizen (i.e., one hot meal daily, the necessary clothing, and shelter). Based on this, we may perceive the connection with the concept of poverty, which is often mistaken for the subsistence minimum concept. Since the poverty threshold is not explicitly defined in Slovakia, we believe that the threshold of the subsistence minimum may serve as its expression. It is necessary to emphasize that the concept of poverty itself is not anchored by legislation, and also that the official statistic reports do not show the number of poor people in the way that the European Union does through Eurostat.

Act No. 601/2003 Coll. on the subsistence minimum reflects the subsistence and minimum social income in this way. The amount of the subsistence minimum and its changes may influence economic categories. Undoubtedly, the subsistence minimum, as a tool of social policy of the state, can be viewed as having a causative relation to tax policy. Change in the amount of the subsistence minimum influences the application of several provisions of Act No. 595/2003 Coll. on Income Tax as amended by later regulations (hereinafter referred to as “AIT”). In connection with the natural person’s income tax, the subsistence living amount influences the determination of the amount of tax bonuses, the nontaxable part of the tax base related to a taxpayer and dependent spouse, some occasional tax-free income, the income threshold for the purposes of determining the obligation to submit an income tax return, a minimum pension, early retirement pensions, and so forth.

Table 3 presents an overview of the development of the subsistence minimum in the Slovak Republic. We only see a slight increase in the level of the subsistence minimum in the time period examined.

The Act of the subsistence minimum itself does not give rise to the entitlement to welfare. It is the basic regulation for the application of other legal regulations, which either give rise to the entitlement to a certain welfare or to a discount from a certain payment (

Rievajová 2006), for example, the application of a tax credit.

The social status of a citizen in the state has the principal significance; it influences the development of its personality quality and, last but not least, reflects the obtained degree of democracy in the specific state. The Slovak Republic belongs undoubtedly to the democratic states and makes every effort to follow the “welfare state” foundations laid in the middle years of the 20th century. It admits the need for interventions into the state economy and is aware of its responsibility for the social situation of its population.

The social policy of the state, enforced by its instruments, being legal or economic ones, ensures the social protection of citizens and fulfils their social securities. What implementation of the right to dignity would it be like without the conditions for education, exercise of paid activity, for material things under the situations given by the objective law (illness, old age, unemployment, etc.), or for bringing up children?

In the fulfilment of these aims, the social policy of the state, in its various forms, has an irreplaceable role. Most citizens refer to the problems of social security of citizens and the satisfaction of their material and spiritual needs when talking about social policy. They think that it includes the state’s social support benefits, social insurance, and social assistance. The tax policy—a kind of policy with the nature of the economic instrument—undoubtedly shapes the form of the social policy in a state. The opinions of some theorists make us certain that the tax system and tax assessment in the framework of the tax system present the results of specific political forces, as well as various ideological and interest groups. The tax assessment should be based on certain principles, which should be determined at the creation of fiscal rules (

Bujňáková 2006).

The measures adopted in the tax policy are to be directed towards the creation of sufficient financial means for ensuring the fulfilment of the state’s functions. This is the reason why economic and behavioral models of tax compliance should receive increased attention and consideration from governments (

Batrancea and Nichita 2012).

The amount of tax collected should ensure the sufficient resources for activities in the public sector and for governmental expenditures in accordance with the Finance Act. The structure of tax assessment and the tax amount influences the willingness of foreign investors to do business in the territory of the Slovak Republic, the behavior of domestic entrepreneurs, and last but not least, the behavior of all consumers of goods and services. The influence of the tax policy on the living standard of citizens is obvious.

The significance of the “national” tax policy did not decrease even after the accession of the states to the European Union, despite the fact that particular states implement the directives and regulations of the European Union into their tax assessments (

Krunková 2007). The tax policy of the Member States does not fall under the common competences of the Union and its Members, nor under the exclusive competence of the Union bodies.

The social policy can also be understood as the effort to improve a certain way of life. According to

Krebs (

2005), ‘the social policy is the policy which is primarily oriented towards humans, to the development and cultivation of their living conditions and dispositions, towards the development of their personality and quality of their life’.

Policy, including tax policy, should act in the direction of objective and scientifically based trends. It means that, as the activity, it assumes expertise and professionalism, including the ability to correctly assess the conditions, time, means, ways, forms, and aims. Therefore, its practical implementation should be the result of a consensus of political forces, which promote certain theoretical concepts as well as partial interests, and of course, it should be the result of economic possibilities, national specifications, traditions, and so on. Some authors consider policy to be a pleonasm, since ‘every policy, in its way, is, in general, social, thus it is the social activity oriented towards “societas”’ (

Muller 1991).

The principle of the legal guarantees of the economic and social rights in the sources of law is accompanied with the economic guarantees. The economic guarantees act at the level of necessity to dispose with the economically viable systems, which financially support the social policy measures. The available financial resources mostly come from collected taxes and social security and health insurance contributions. In this context, the tax (as well as deduction) policy considerably influences the social status of individuals. It directly influences the living standard of citizens, since taxes and deductions are the most important tools for drawing off a portion of natural and legal entities’ income into the public budgets. The result of this is that the citizenry do not participate in the decision-making processes, and thus have limited responsibility (

Mihalik 2015). The importance of the tax policy is partly in the creation of social safety in the country, and its implementation (especially the tax imposition and collection) is also important in guaranteeing the social needs of citizens in the context of the state providing financial or social support to the most poor and dependent persons.

6. A Reflection on Tax Justice

The science of the social security law considers the allocation of the social means to be one of several aspects of the social justice principle. The definition of the principle of social justice is a continuous dynamic process, since it is a combination of particular appropriate principles regarding the satisfaction of citizens’ needs. However, in this context, it is necessary to state, as according to

Barinková (

2007), that ‘the principle of the all-society solidarity depends on the state budget economic possibilities’.

Taxation presents the economic and legal institution through which a part of the financial means of legal and natural persons is taken away with power in order to ensure state and other public needs. The function of the instrument of power that ensures these needs is still an inherent characteristic of taxes. Taxes are always imposed without the consent of the subject towards which the tax obligation is oriented. Therefore, along with the imposition and collection of taxes, the economic, social, and especially ethical reasons for their imposition and collection have always been a subject of discussion (

Babčák 2015).

The abovementioned is accompanied by the problems relating to society’s adaptation to their existence. The subject of the tax obligation has had no opportunity—considering the historical view—to express their opinion of its implementation, and has been forced to respect the legal acts that have constituted the specific tax obligations. On that basis, we can state that the social status of a citizen has been forming, from the point of view of the tax imposition and collection, independently of his/her will. In general, taxes present considerable economic and social consequences for taxpayers. The taxes’ imposition and their subsequent collection mostly produce an adverse public reaction. It is difficult to imagine a situation in which the tax implementation could be accepted positively, excluding the case when the most of public admits the need for tax implementation as “a kind of a disciplinary action” in relation to the performance of some activities or sale of some products (e.g., duties on tobacco and cigarette products).

Therefore, can we speak about tax justice? The public perceives the idea of tax justice very sensitively, as a component of the justice and law relationship. The principle of tax justice presents not only moral and ethical aspects of perception, but is also a legal phenomenon. It is the attribute of tax and legal relations which can, positively as well as negatively, influence the approaches of citizens to changes in the tax system.

The tax system takes its shape in the society on the basis of long-term as well as short-term factors. We consider the efficiency and justice of the tax system to be features of the same intensity on the scale. The course of tax policy considerably depends on the tax principles applied by the state, through which the government influences the tax policy and the business environment as well as the population’s living standard.

The principle of tax justice is inherent for tax policy, and similarly, at the implementation of social policy, the principle of social justice is applied. There is a question left open in the sphere of justice of a generally unidentifiable idea about its content. There are a number of subjects implementing social policy, among which the state plays a dominant role due to its capability to dispose of public authority and ability to adopt the legal regulations binding the population. The public authority can organize the functioning of social policy on the widest basis, as well as its funding and redistribution.

In this connection, it is indisputable that tax policy, as a component of the economic policy of the state, influences the macroeconomic aggregates (especially the GDP volume, the rate of inflation, unemployment, etc.). The wording of Article 55 of the Constitution of the Slovak Republic, ‘The economy of the Slovak Republic is based on the principles of a socially and ecologically oriented market economy’, documents the connection between the economic and social development of the society while respecting the ecological aspects of the economy. The concept of ‘social’ commits the state to providing for citizens in the case of certain risks to living conditions, for example, during illness, in old age, due to an industrial accident, unemployment, disability, and so forth. The optimum setting of the tax system is included in the activities in the economic sphere and thus interacts against poverty and social exclusion.

From the point of view of social function and tax justice, the efficient tax system that is unjust is certainly a worse alternative to a less efficient, yet just tax system. Any legislative tax regulation, and especially tax reform, is perceived very sensitively by the tax subjects. The group of legal standards that creates tax law as a subsector of financial law has an indisputable impact on the social position of a natural person. There are several standards of tax law, with the primary goal to mitigate the impact of the implementation of tax obligations on the social status of natural persons.

7. Conclusions

The main goal of social justice in every social and democratic society is to create the social conditions allowing the dignified living of all inhabitants and the obligation to provide at least a subsistence for everybody. In the paper, we have pointed out the fact that the authority of the state to partake in the economic success of an economically active person is not limited to the presence of the minimum wage. We concluded that if we consider the minimum wage to be an economic success, even though it is a reflection of a certain minimum, its guaranteed level by the state has to be different from the subsistence minimum. The subsistence minimum is not considered to be a success by a modern democratic state. The level of the subsistence minimum determines the degree of the tax burden of economically active taxpayers, and it can put the Slovak tax system into a dumping position against tax systems in other European countries. Regarding the level of the tax burden, we emphasized the fact that the tax burden is the reflection of the social status of taxpayers, as a group of economically active subjects. The tools of social policy are able to offer a full picture with self-explanatory values about the state of the social situation of the Slovak society, and therefore can better contribute to the understanding of tax policy in the Slovak republic. We have equally emphasized the fact that the amount of the minimum wage has been the subject of many political discussions in the past, with different opinions, such as that a high minimum wage increases the level of unemployment, or on the other hand, the lowest possible minimum wage can cause a decrease in the living standard of the society. Therefore, it is crucial to find the appropriate compromise and to derive the amount of the minimum wage from upfront, specified socioeconomical indicators, for example, the relation to imposing tax on the minimum wage.

The optimal adjustment of the tax system and any legislative tax regulation is viewed by tax subjects very sensitively and can be viewed as ‘tax injustice’. Taxes are always imposed without the consent of the subject they are aimed at. Therefore, the state should consider the social function of collecting and imposing taxes against the subjects, especially against those that are vulnerable in the labor market.

Income taxation has been seen as a key tool for redistribution, and the state was the arena for discussions of justice (

Dagan 2017).

The answers to the questions previously asked, which we tried to provide, are up to all of us. Only this kind of approach is the basic sign of a ‘democratic society’ which is open to people and based on respecting human dignity and people with varied opinions. In the society which is perceived in this way (we believe that the Slovak Republic could also be perceived in this way in the future), the government, state, and social institutions, which are to be neutral, have the task of guaranteeing social order in tax imposition.

8. Regulations

Act No. 5/2004 Coll. on Employment Services.

Act No. 595/2003 Coll. on Income Tax, as amended by later regulations.

Act No. 601/2003 Coll. on the Subsistence Minimum, as amended by later regulations.

Act No. 599/2003 Coll. About Assistance in Material Need, as amended by later regulations.

III. ÚS 64/2000. Decision from 31 January 2001.