When in Rome, Feel as the Romans Feel: An Emotional Model of Organizational Socialization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundation

2.1. Emotions in Organizational Socialization

2.2. Emotional Expressions in Organizations

2.3. Emotional Culture for Newcomers

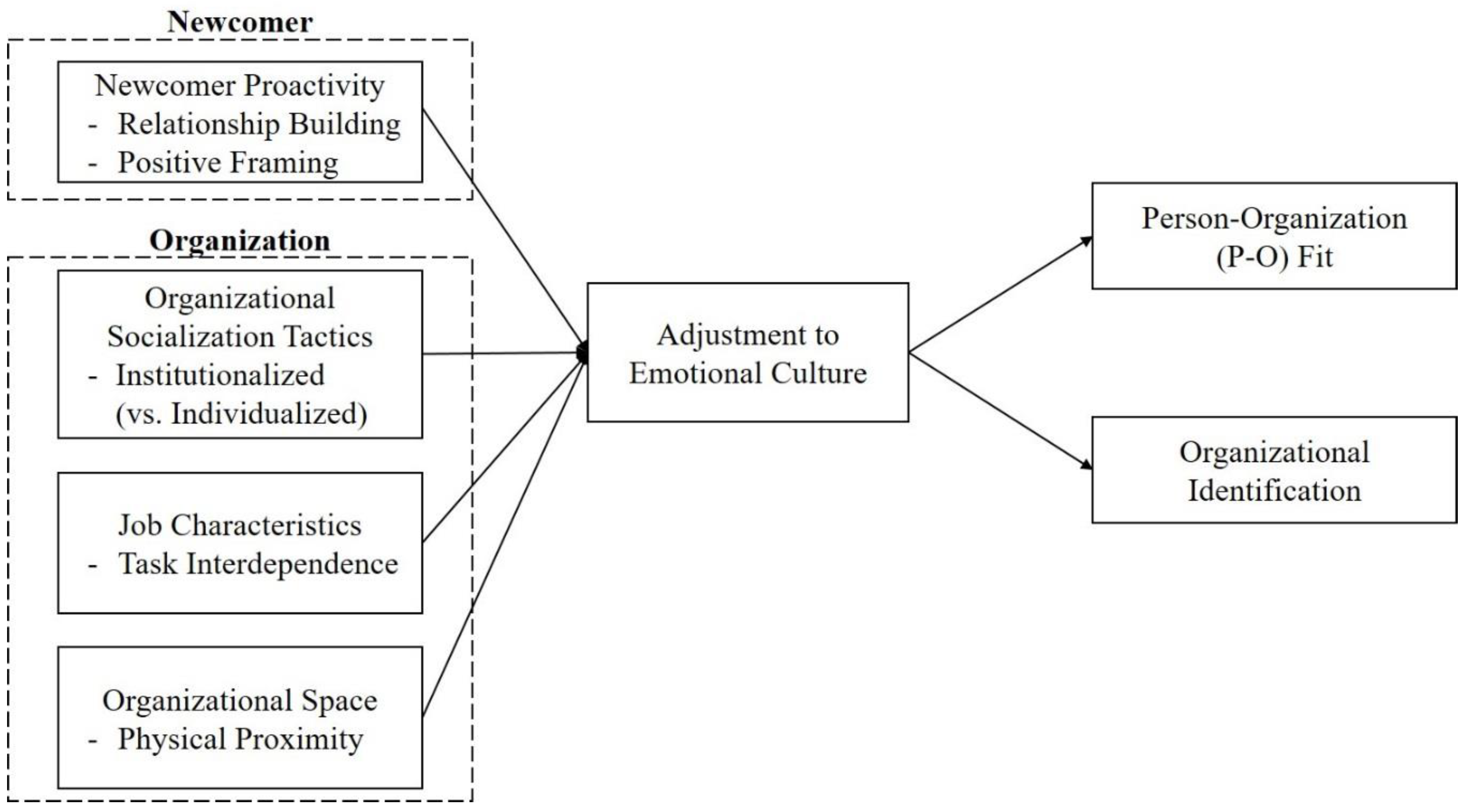

3. Emotional Model of Organizational Socialization

3.1. Newcomers’ Information Acquisition

3.2. Newcomer Proactivity

3.3. Organizational Socialization Tactics

3.4. Task Interdependence

3.5. Physical Proximity

3.6. P–O Fit

3.7. Organizational Identification

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Contribution

4.2. Practical Contribution

4.3. Future Research Direction

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adkins, Cheryl L. 1995. Previous Work Experience and Organizational Socialization: A Longitudinal Examination. Academy of Management Journal 38: 839–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, Francis J. 1967. Scanning the Business Environment. New York: Mac Millan. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Joseph A., S. Douglas Pugh, Alicia A. Grandey, and Markus Groth. 2010. Following Display Rules in Good or Bad Faith? Customer Orientation as a Moderator of the Display Rule-Emotional Labor Relationship. Human Performance 23: 101–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Tammy D., Lillian T. Eby, Georgia T. Chao, and Talya N. Bauer. 2017. Taking Stock of Two Relational Aspects of Organizational Life: Tracing the History and Shaping the Future of Socialization and Mentoring Research. Journal of Applied Psychology 102: 324–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, Tammy D., Stacy E. McManus, and Joyce E.A. Russell. 1999. Newcomer Socialization and Stress: Formal Peer Relationships as a Source of Support. Journal of Vocational Behavior 54: 453–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Thomas J. 1997. Managing the Flow of Technology: Technology Transfer and the Dissemination of Technological Information with the R&D Organization. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262010481. [Google Scholar]

- Ashford, Susan J., and J. Stewart Black. 1996. Proactivity during Organizational Entry: The Role of Desire for Control. Journal of Applied Psychology 81: 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashford, Susan J., and Samir Nurmohamed. 2012. From Past to Present and into the Future: A Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Socialization Literature. In Oxford Handbook of Organizational Socialization. Edited by Connie W. Wanberg. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 8–24. ISBN 9780199763672. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, Blake E., Alan M. Saks, and Raymond T. Lee. 1998. Socialization and Newcomer Adjustment: The Role of Organizational Context. Human Relations 51: 897–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, Blake E., and Alan M. Saks. 2002. Feeling Your Way: Emotion and Organizational Entry. In Emotions in the workplace. Edited by Robert G. Lord, Richard J. Klimoski and Ruth Kanfer. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, pp. 331–369. ISBN 0787957364. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, Blake E., and Ronald H. Humphrey. 1993. Emotional Labor in Service Roles: The Influence of Identity. Academy of Management Review 18: 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, Blake E., David M. Sluss, and Alan M. Saks. 2007. Socialization Tactics, Proactive Behavior, and Newcomer Learning: Integrating Socialization Models. Journal of Vocational Behavior 70: 447–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, Blake K., and Alan M. Saks. 1996. Socialization Tactics: Longitudinal Effects on Newcomer Adjustment. Academy of Management Journal 39: 149–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkanasy, Neal M., Ashlea C. Troth, Sandra A. Lawrence, and Peter J. Jordan. 2017. Emotions and Emotional Regulation in HRM: A Multi-Level Perspective. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources. Edited by M. Ronald Buckley, Anthony R. Wheeler and Jonathon R. B. Halbesleben. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, vol. 35, pp. 1–52. ISBN 9781787147096. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, Albert. 1977. Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Barsade, Sigal G., and Donald E. Gibson. 2007. Why Does Affect Matter in Organizations? Academy of Management Perspectives 21: 36–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsade, Sigal G., and Olivia A. O’Neill. 2014. What’s Love Got to Do with It? A Longitudinal Study of the Culture of Companionate Love and Employee and Client Outcomes in a Long-Term Care Setting. Administrative Science Quarterly 59: 551–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, Bernard M., and Bruce J. Avolio. 1993. Transformational Leadership and Organizational Culture. Public Administration Quarterly 17: 112–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batistič, Saša. 2018. Looking Beyond-Socialization Tactics: The Role of Human Resource Systems in the Socialization Process. Human Resource Management Review 28: 220–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Talya N., and Berrin Erdogan. 2012. Organizational Socialization Outcomes: Now and into the Future. In Oxford Handbook of Organizational Socialization. Edited by Connie W. Wanberg. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 97–112. ISBN 9780199763672. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Talya N., Elizabeth W. Morrison, and Ronda R. Callister. 1998. Organizational Socialization: A Review and Directions for Future Research. In Research in Personnel and Human Resource Management. Edited by Gerald R. Ferris. Greenwich: JAI Press, vol. 16, pp. 149–214. ISBN 9780762303687. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Talya N., Todd Bodner, Berrin Erdogan, Donald M. Truxillo, and Jennifer S. Tucker. 2007. Newcomer Adjustment during Organizational Socialization: A Meta-Analytic Review of Antecedents, Outcomes, and Methods. Journal of Applied Psychology 92: 707–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzinger, Diana. 2016. Organizational Socialization Tactics and Newcomer Information Seeking in the Contingent Workforce. Personnel Review 45: 743–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman Brown, Reva, and Ian Brooks. 2002. Emotion at Work: Identifying the Emotional Climate of Night Nursing. Journal of Management in Medicine 16: 327–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnholtz, Jeremy P., Michael D. Cohen, and Susannah V. Hoch. 2007. Organizational Character: On the Regeneration of Camp Poplar Grove. Organization Science 18: 315–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, Stephen P., and Rob Cross. 2003. A Relational View of Information Seeking and Learning in Social Networks. Management Science 49: 432–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, David E., Gerald E. Ledford, and Barry R. Nathan. 1991. Hiring for the Organization, Not the Job. Academy of Management Perspectives 5: 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, Daniel M., and Charles K. Parsons. 2001. Socialization Tactics and Person-Organization Fit. Personnel Psychology 54: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, Jamie L., and Eric E. McCollum. 2002. Conceptualizations of Emotion Research in Organizational Contexts. Advances in Developing Human Resources 4: 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Georgia T. 2007. Mentoring and Organizational Socialization. In The Handbook of Mentoring at Work: Theory, Research, and Practice. Edited by Belle R. Ragins and Kathy E. Kram. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 179–196. ISBN 9781412916691. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, Georgia T., Anne M. O’Leary-Kelly, Samantha Wolf, Howard J. Klein, and Philip D. Gardner. 1994. Organizational Socialization: Its Content and Consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology 79: 730–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoforou, Paraskevi S., and Blake E. Ashforth. 2015. Revisiting the Debate on the Relationship between Display Rules and Performance: Considering the Explicitness of Display Rules. Journal of Applied Psychology 100: 249–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colarelli, Stephen M., Roger A. Dean, and Constantine Konstans. 1987. Comparative Effects of Personal and Situational Influences on Job Outcomes of New Professionals. Journal of Applied Psychology 72: 558–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper-Thomas, Helena D., Annelies Van Vianen, and Neil Anderson. 2004. Changes in Person–Organization Fit: The Impact of Socialization Tactics on Perceived and Actual P–O Fit. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 13: 52–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper-Thomas, Helena, and Neil Anderson. 2002. Newcomer Adjustment: The Relationship between Organizational Socialization Tactics, Information Acquisition and Attitudes. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 75: 423–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crant, J. Michael. 2000. Proactive Behavior in Organizations. Journal of Management 26: 435–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cooman, Rein, Sara De Gieter, Roland Pepermans, Sabrina Hermans, Cindy Du Bois, Ralf Caers, and Marc Jegers. 2009. Person–Organization Fit: Testing Socialization and Attraction–Selection–Attrition Hypotheses. Journal of Vocational Behavior 74: 102–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denham, Susanne A., Hideko H. Bassett, and Todd M. Wyatt. 2010. Gender Differences in the Socialization of Preschoolers’ Emotional Competence. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 128: 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diefendorff, James M., and Erin M. Richard. 2003. Antecedents and Consequences of Emotional Display Rule Perceptions. Journal of Applied Psychology 88: 284–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diefendorff, James M., and Gary J. Greguras. 2009. Contextualizing Emotional Display Rules: Examining the Roles of Targets and Discrete Emotions in Shaping Display Rule Perceptions. Journal of Management 35: 880–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefendorff, James M., Erin M. Richard, and Meredith H. Croyle. 2006. Are Emotional Display Rules Formal Job Requirements? Examination of Employee and Supervisor Perceptions. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 79: 273–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Ruolian, Michelle K. Duffy, and Jason D. Shaw. 2011. The Organizational Socialization Process: Review and Development of a Social Capital Model. Journal of Management 37: 127–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, Daniel C., and Barton A. Weitz. 1990. Summer Interns: Factors Contributing to Positive Developmental Experiences. Journal of Vocational Behavior 37: 267–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fineman, Stephen. 1993. Organizations as Emotional Arenas. In Emotion in Organizations. Edited by Stephen Fineman. London: Sage, pp. 9–35. ISBN 9780761966258. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Cynthia D. 1986. Organizational Socialization: An Integrative Review. In Research in Personnel and Human Resource Management. Edited by Kendrith M. Rowland and Gerald R. Ferris. Greenwich: JAI Press, vol. 4, pp. 101–45. ISBN 9780892326068. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, Steven L. 1990. Social Structural Effects on Emotion. In Research agendas in the sociology of emotions. Edited by Theodore D. Albany Kemper. New York: State University of New York Press, pp. 145–79. ISBN 9780791402696. [Google Scholar]

- Grandey, Alicia A. 2003. When ‘The Show Must Go On’: Surface Acting and Deep Acting as Determinants of Emotional Exhaustion and Peer-Rated Service Delivery. Academy of Management Journal 46: 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, Alicia A., Anita P. Tam, and Analea L. Brauburger. 2002. Affective States and Traits in the Workplace: Diary and Survey Data from Young Workers. Motivation and Emotion 26: 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, Alicia A., Glenda M. Fisk, and Dirk D. Steiner. 2005a. Must Service with a Smile Be Stressful? The Moderating Role of Personal Control for American and French Employees. Journal of Applied Psychology 90: 893–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandey, Alicia A., Glenda M. Fisk, Anna S. Mattila, Karen J. Jansen, and Lori A. Sideman. 2005b. Is ‘Service with a Smile’ Enough? Authenticity of Positive Displays during Service Encounters. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 96: 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruman, Jamie A., Alan M. Saks, and David I. Zweig. 2006. Organizational Socialization Tactics and Newcomer Proactive Behaviors: An Integrative Study. Journal of Vocational Behavior 69: 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Seongwook. 2018. Surface Acting and Job-Related Affective Wellbeing: Preventing Resource Loss Spiral and Resource Loss Cycle for Sustainable Workplaces. Sustainability 10: 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J. Richard, and Greg R. Oldham. 1975. Development of the Job Diagnostic Survey. Journal of Applied Psychology 60: 159–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Härtel, Charmine E. J. 2008. How to Build a Healthy Emotional Culture and Avoid a Toxic Culture. In Research Companion to Emotion in Organization. Edited by Sir C. Cooper and Neal M. Ashkanasy. Cheltenham: Edwin Elgar Publishing, pp. 1260–91. ISBN 9781845426378. [Google Scholar]

- Härtel, Charmine E. J., Helen Gough, and Günter F. Härtel. 2008. Work-Group Emotional Climate, Emotion Management Skills, and Service Attitudes and Performance. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 46: 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haski-Leventhal, Debbie, and David Bargal. 2008. The Volunteer Stages and Transitions Model: Organizational Socialization of Volunteers. Human Relations 61: 67–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Hongwei, and Andrew D. Brown. 2013. Organizational Identity and Organizational Identification: A Review of the Literature and Suggestions for Future Research. Group & Organization Management 38: 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, Ursula, and Agneta Fischer. 2014. Emotional Mimicry: Why and When We Mimic Emotions. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 8: 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 1979. Emotion Work, Feeling Rules, and Social Structure. American Journal of Sociology 85: 551–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, Brian J., and David J. Woehr. 2006. A Quantitative Review of the Relationship between Person–Organization Fit and Behavioral Outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior 68: 389–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, C., John Kammeyer-Mueller, and B. Livingston. 2012. The Odd One Out: How Newcomers Who Are Different Become Adjusted. In Oxford Handbook of Organizational Socialization. Edited by Connie W. Wanberg. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 115–38. ISBN 9780199763672. [Google Scholar]

- Jablin, Fredric M. 2001. Organizational Entry, Assimilation, and Disengagement/Exit. In The New Handbook of Organizational Communication: Advances in Theory, Research, and Method. Edited by Fredric M. Jablin and Linda L. Putnam. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 732–818. ISBN 9781412915250. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Gareth R. 1986. Socialization Tactics, Self-Efficacy, and Newcomers’ Adjustments to Organizations. Academy of Management Journal 29: 262–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammeyer-Mueller, John D., and Connie R. Wanberg. 2003. Unwrapping the Organizational Entry Process: Disentangling Multiple Antecedents and Their Pathways to Adjustment. Journal of Applied Psychology 88: 779–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kammeyer-Mueller, John, Connie R. Wanberg, Alex Rubenstein, and Zhaoli Song. 2013. Support, Undermining, and Newcomer Socialization: Fitting in during the First 90 Days. Academy of Management Journal 56: 1104–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, Ralph. 1985. Organizational Stress and Early Socialization Experiences. In Human Stress and Cognition in Organizations: An Integrative Perspective. Edited by Terry A. Beehr and Rabi S. Bhagat. New York: Wiley, pp. 117–39. ISBN 9780471869542. [Google Scholar]

- Kelman, Herbert C. 1961. Three Processes of Social Influence. Public Opinion Quarterly 25: 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiggundu, Moses N. 1981. Task Interdependence and the Theory of Job Design. Academy of Management Review 6: 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Tae-Yeol, Daniel M. Cable, and Sang-Pyo Kim. 2005. Socialization Tactics, Employee Proactivity, and Person-Organization Fit. Journal of Applied Psychology 90: 232–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, Howard J., and Aden E. Heuser. 2008. The Learning of Socialization Content: A Framework for Researching Orientating Practices. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management. Edited by Joseph J. Martocchio. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, vol. 27, pp. 279–336. ISBN 9781848550049. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Howard J., Jinyan Fan, and Kristopher J. Preacher. 2006. The Effects of Early Socialization Experiences on Content Mastery and Outcomes: A Mediational Approach. Journal of Vocational Behavior 68: 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopelman, Richard E., Arthur E. Brief, and Richard A. Guzzo. 1990. The Role of Climate and Culture in Productivity. In Organizational Climate and Culture. Edited by Benjamin Schneider. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, pp. 282–318. ISBN 9781555422875. [Google Scholar]

- Korte, Russell F. 2009. How Newcomers Learn the Social Norms of an Organization: A Case Study of the Socialization of Newly Hired Engineers. Human Resource Development Quarterly 20: 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krackhardt, David. 1994. Constraints on the Interactive Organization as an Ideal Type. In The Post-Bureaucratic Organization: New Perspective on Organizational Change. Edited by Charles Heckscher and Anne Donnellon. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 211–22. ISBN 9780803957183. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, Michael W. 2010. Organizational Socialization: Joining and Leaving Organizations. Cambridge: Polity Press. ISBN 9780745646343. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, Michael W., and Jon A. Hess. 2002. Communication Rules for the Display of Emotions in Organizational Settings. Management Communication Quarterly 16: 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof, Amy L. 1996. Person-Organization Fit: An Integrative Review of Its Conceptualizations, Measurement, and Implications. Personnel Psychology 49: 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapointe, Émilie, Christian Vandenberghe, and Jean-Sébastien Boudrias. 2014. Organizational Socialization Tactics and Newcomer Adjustment: The Mediating Role of Role Clarity and Affect-Based Trust Relationships. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 87: 599–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, Harry. 1965. Reciprocation: The Relationship between Man and Organization. Administrative Science Quarterly 9: 370–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, Meryl R. 1990. Acculturation in the Workplace: Newcomers as Lay Ethnographers. In Organizational Climate and Culture. Edited by Benjamin Schneider. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, pp. 85–129. ISBN 9781555422875. [Google Scholar]

- Loury, Linda D. 2006. Some Contacts Are More Equal than Others: Informal Networks, Job Tenure, and Wages. Journal of Labor Economics 24: 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, Günter W., and Joachim C. Brunstein. 2001. The Role of Personal Work Goals in Newcomers’ Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment: A Longitudinal Analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 86: 1034–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Major, Debra A., and Steve W. J. Kozlowski. 1997. Newcomer Information Seeking: Individual and Contextual Influences. International Journal of Selection and Assessment 5: 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manz, Charles C., and Henry P. Sims, Jr. 1981. Vicarious Learning: The Influence of Modeling on Organizational Behavior. Academy of Management Review 6: 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignerey, James T., Rebecca B. Rubin, and William I. Gorden. 1995. Organizational Entry: An Investigation of Newcomer Communication Behavior and Uncertainty. Communication Research 22: 54–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Vernon D. 1996. An Experimental Study of Newcomers’ Information Seeking Behaviors during Organizational Entry. Communication Studies 47: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Vernon D., and Fredric M. Jablin. 1991. Information Seeking during Organizational Entry: Influences, Tactics, and a Model of the Process. Academy of Management Review 16: 92–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, Andrew M., Theresa M. Glomb, and Charles Hulin. 2005. Experience Sampling Mood and Its Correlates at Work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 78: 171–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzberg, Henry. 1975. The Manager’s Job. Harvard Business Review 53: 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Moreland, Richard L., and John M. Levine. 2002. Socialization and Trust in Work Groups. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 5: 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, Frederick P., and Stephen E. Humphrey. 2006. The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and Validating a Comprehensive Measure for Assessing Job Design and the Nature of Work. Journal of Applied Psychology 91: 1321–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, J. Andrew, and Daniel C. Feldman. 1996. The Dimensions, Antecedents, and Consequences of Emotional Labor. Academy of Management Review 21: 986–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, Elizabeth W. 1993a. Longitudinal Study of the Effects of Information Seeking on Newcomer Socialization. Journal of Applied Psychology 78: 173–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, Elizabeth W. 1993b. Newcomer Information Seeking: Exploring Types, Modes, Sources, and Outcomes. Academy of Management Journal 36: 557–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, Elizabeth W. 2002. Newcomers’ Relationships: The Role of Social Network Ties during Socialization. Academy of Management Journal 45: 1149–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Debra L., and James Campbell Quick. 1991. Social Support and Newcomer Adjustment in Organizations: Attachment Theory at Work? Journal of Organizational Behavior 12: 543–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nifadkar, Sushil, Anne S. Tsui, and Blake E. Ashforth. 2012. The Way You Make Me Feel and Behave: Supervisor-Triggered Newcomer Affect and Approach-Avoidance Behavior. Academy of Management Journal 55: 1146–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, Ikujiro. 1994. A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation. Organization Science 5: 14–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, Olivia Amanda, and Nancy P. Rothbard. 2017. Is Love All You Need? The Effects of Emotional Culture, Suppression, and Work–Family Conflict on Firefighter Risk-Taking and Health. Academy of Management Journal 60: 78–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, Charles A., III, Jennifer Chatman, and David F. Caldwell. 1991. People and Organizational Culture: A Profile Comparison Approach to Assessing Person-Organization Fit. Academy of Management Journal 34: 487–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, Charles A., and Jennifer Chatman. 1986. Organizational Commitment and Psychological Attachment: The Effects of Compliance, Identification, and Internalization on Prosocial Behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology 71: 492–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroff, Cheri, and Steve WJ Kozlowski. 1992. Organizational Socialization as a Learning Process: The Role of Information Acquisition. Personnel Psychology 45: 849–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, Brian, Agneta H. Fischer, and Antony S. R. Manstead. 2005. Emotion in Social Relations: Cultural, Group, and Interpersonal Processes. New York: Psychology Press. ISBN 9781841690452. [Google Scholar]

- Perrot, Serge, Talya N. Bauer, David Abonneau, Eric Campoy, Berrin Erdogan, and Robert C. Liden. 2014. Organizational Socialization Tactics and Newcomer Adjustment: The Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support. Group & Organization Management 39: 247–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinelli, Thomas E. 1991. The Information-Seeking Habits and Practices of Engineers. Science & Technology Libraries 11: 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plas, Jeanne M., and Kathleen V. Hoover-Dempsey. 1988. Working up a Storm Anger, Anxiety, Joy, and Tears on the Job. New York: Norton. ISBN 9780393336801. [Google Scholar]

- Price, Sheri L. 2009. Becoming a Nurse: A Meta-Study of Early Professional Socialization and Career Choice in Nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing 65: 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafaeli, Anat, and Robert I. Sutton. 1987. Expression of Emotion as Part of the Work Role. Academy of Management Review 12: 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafaeli, Anat. 1989. When Clerks Meet Customers: A Test of Variables Related to Emotional Expressions on the Job. Journal of Applied Psychology 74: 385–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravid, Shy, Anat Rafaeli, and Alicia Grandey. 2010. Expressions of Anger in Israeli Workplaces: The Special Place of Customer Interactions. Human Resource Management Review 20: 224–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichers, Arnon E. 1987. An Interactionist Perspective on Newcomer Socialization Rates. Academy of Management Review 12: 278–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, Harry T., and W. Andrew Collins. 2004. Relationships, Human Behavior, and Psychological Science. Current Directions in Psychological Science 13: 233–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, Linda, and Robert Eisenberger. 2002. Perceived Organizational Support: A Review of the Literature. Journal of Applied Psychology 87: 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, Ronald E., and Carolyn Aydin. 1991. Attitudes toward New Organizational Technology: Network Proximity as a Mechanism for Social Information Processing. Administrative Science Quarterly 36: 219–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riforgiate, Sarah E., and Maria Komarova. 2017. Emotion at Work. In International Encyclopedia of Organizational Communication. Edited by Craig R. Scott and Laurie K. Lewis. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riketta, Michael. 2005. Organizational Identification: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior 66: 358–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross Wooldridge, Barbara, and Barbara D. Minsky. 2002. The Role of Climate and Socialization in Developing Interfunctional Coordination. The Learning Organization 9: 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, Alan M., and Blake E. Ashforth. 1997. Organizational Socialization: Making Sense of the Past and Present as a Prologue for the Future. Journal of Vocational Behavior 51: 234–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, Alan M., and Jamie A. Gruman. 2012. Getting Newcomers on Board: A Review of Socialization Practices and Introduction to Socialization Resources Theory. In Oxford Handbook of Organizational Socialization. Edited by Connie W. Wanberg. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 27–55. ISBN 9780199763672. [Google Scholar]

- Saks, Alan M., Krista L. Uggerslev, and Neil E. Fassina. 2007. Socialization Tactics and Newcomer Adjustment: A Meta-Analytic Review and Test of a Model. Journal of Vocational Behavior 70: 413–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Benjamin. 1987. The People Make the Place. Personnel Psychology 40: 437–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, Clifton, and Karen Kroman Myers. 2005. The Socialization of Emotion: Learning Emotion Management at the Fire Station. Journal of Applied Communication Research 33: 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, Scott E., Maria L. Kraimer, and J. Michael Crant. 2001. What Do Proactive People Do? A Longitudinal Model Linking Proactive Personality and Career Success. Personnel Psychology 54: 845–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sias, Pahtricia M., and Tammie D. Wyers. 2001. Employee Uncertainty and Information-Seeking in Newly Formed Expansion Organizations. Management Communication Quarterly 14: 549–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, Patricia A., and Linda K. Stroh. 2004. Gender Differences: Emotional Expression and Feelings of Personal Inauthenticity. Journal of Applied Psychology 89: 715–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, Laura G. E., Catherine E. Amiot, Victor J. Callan, Deborah J. Terry, and Joanne R. Smith. 2012. Getting New Staff to Stay: The Mediating Role of Organizational Identification. British Journal of Management 23: 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, Robert I. 1991. Maintaining Norms about Expressed Emotions: The Case of Bill Collectors. Administrative Science Quarterly 36: 245–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, Henri. 1978. Differentiation between Social Groups: Studies in the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. London: Academic Press. ISBN 9780126825503. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Leigh, and Janice Nadler. 2002. Negotiating via Information Technology: Theory and Application. Journal of Social Issues 58: 109–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidwell, Michael, and Patricia Sias. 2005. Personality and Information Seeking: Understanding How Traits Influence Information-Seeking Behaviors. The Journal of Business Communication 42: 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totterdell, Peter, and David Holman. 2003. Emotion Regulation in Customer Service Roles: Testing a Model of Emotional Labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 8: 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tschan, Franziska, Sylvie Rochat, and Dieter Zapf. 2005. It’s Not Only Clients: Studying Emotion Work with Clients and Co-Workers with an Event-Sampling Approach. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 78: 195–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kleef, Gerben A. 2009. How Emotions Regulate Social Life: The Emotions as Social Information (EASI) Model. Current Directions in Psychological Science 18: 184–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Maanen, John, and Edgar H. Schein. 1979. Toward a Theory of Organizational Socialization. In Research in Organizational Behavior: An Annual Series of Analytical Essays and Critical Reviews. Edited by Barry M. Staw and Larry L. Cummings. Greenwich: JAI Press, vol. 1, pp. 209–64. ISBN 9780892320455. [Google Scholar]

- Van Maanen, John. 1978. People Processing: Strategies of Organizational Socialization. Organizational Dynamics 7: 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vianen, Annelies E. M., and Irene E. De Pater. 2012. Content and Development of Newcomer Person–Organization Fit: An Agenda for Future Research. In Oxford Handbook of Organizational Socialization. Edited by Connie W. Wanberg. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 139–57. ISBN 9780199763672. [Google Scholar]

- Wanberg, Connie R., and John D. Kammeyer-Mueller. 2000. Predictors and Outcomes of Proactivity in the Socialization Process. Journal of Applied Psychology 85: 373–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanberg, Connie R., and Yongjun Choi. 2012. Moving Forward: Next Steps for Advancing the Research and Practice of Employee Socialization. In Oxford Handbook of Organizational Socialization. Edited by Connie W. Wanberg. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 339–46. ISBN 9780199763672. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Mo, Yujie Zhan, Elizabeth McCune, and Donald Truxillo. 2011. Understanding Newcomers’ Adaptability and Work-Related Outcomes: Testing the Mediating Roles of Perceived P-E Fit Variables. Personnel Psychology 64: 163–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Mo, John Kammeyer-Mueller, Yihao Liu, and Yixuan Li. 2015. Context, Socialization, and Newcomer Learning. Organizational Psychology Review 5: 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, Howard M. 1977. Subordinate Imitation of Supervisor Behavior: The Role of Modeling in Organizational Socialization. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 19: 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesson, Michael J., and Celile Itir Gogus. 2005. Shaking Hands with a Computer: An Examination of Two Methods of Organizational Newcomer Orientation. Journal of Applied Psychology 90: 1018–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wingfield, Adia Harvey. 2010. Are Some Emotions Marked ‘Whites Only’? Racialized Feeling Rules in Professional Workplaces. Social Problems 57: 251–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, Y. When in Rome, Feel as the Romans Feel: An Emotional Model of Organizational Socialization. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100197

Choi Y. When in Rome, Feel as the Romans Feel: An Emotional Model of Organizational Socialization. Social Sciences. 2018; 7(10):197. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100197

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Yongjun. 2018. "When in Rome, Feel as the Romans Feel: An Emotional Model of Organizational Socialization" Social Sciences 7, no. 10: 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100197

APA StyleChoi, Y. (2018). When in Rome, Feel as the Romans Feel: An Emotional Model of Organizational Socialization. Social Sciences, 7(10), 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100197