Student Choice in Higher Education—Reducing or Reproducing Social Inequalities?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Emergence of The Rationale for Greater Student Choice And Marketization of HE

2.1. The 1997 Dearing Report

“recommendations on how the purposes, shape, structure, size and funding of higher education, including support for students, should develop to meet the needs of the United Kingdom over the next 20 years”.

“increasing participation in higher education is a necessary and desirable objective of national policy over the next 20 years. This must be accompanied by the objective of reducing the disparities in participation in higher education between groups and ensuring that higher education is responsive to the aspirations and distinctive abilities of individuals”.

“There have been important changes since Robbins in the nature of the relationship between government and those who receive public funds. There have been moves towards the stronger interplay of market forces, in order to increase competition between providers and thereby encourage efficiency, and an emphasis on standards and accountability. These general trends have been reflected in higher education through the introduction of new funding methodologies, new approaches to quality assurance and an emerging focus on the ‘consumer’ rather than the ‘provider’. Although the emphasis and the mechanisms may change over time, we expect there to be a continuing concern to promote efficiency, informed choice, quality and accountability over the next twenty years.”

2.2. The 1998 Labour Government Reforms

“The Act puts in place new funding arrangements for higher education designed to address the funding crisis we inherited. It modernises student support in higher education in a way that is fair to individual students and their families. Savings from the new arrangements will be used to improve quality, standards and opportunities for all in further and higher education”.

“The new system of student support balances the contributions made by individuals and the community as a whole. It is more progressive than in the past, and it directs resources to those who need them most. Critically, it secures an income stream for higher education of fee contributions and loan repayments, which underpins expansion and the widening of opportunities”.

2.3. The 2003 White Paper and the 2004 Higher Education Act

“….in an era when students are being asked to contribute more to the costs of their tuition, to reflect the benefits it brings them, their expectations of teaching quality will rise. The Government believes that student choice will be an increasingly important driver of teaching quality, as students choose the good-quality courses that will bring them respected and valuable qualifications and give them the higher-level skills that they will need during their working life.”

“Our system is not good enough at offering students real choice about how they learn. Higher education should be a choice open to everyone with the potential to benefit—including older people in the workforce who want to update their skills. There are not enough choices for flexible study—including part-time courses, sandwich courses, distance learning, and e-learning—and there must be an increasingly rich variety of subjects to study, which keep pace with changes in society and the economy.”

2.4. The 2010 Browne Report

“What we recommend is a radical departure from the existing way in which HEIs are financed. Rather than the Government providing a block grant for teaching to HEIs, their finance now follows the student who has chosen and been admitted to study. Choice is in the hands of the student”.

“Students will control a much larger proportion of the investment in higher education. They will decide where the funding should go; and institutions will compete to get it. As students will be paying more than in the current system, they will demand more in return”.

“the same upfront support for the costs of learning is extended to part time students as well. Higher education will be free at the point of entry for all students, regardless of the mode of study, giving them more choice about how they choose to study—and where”.

“Part time students should be treated the same as full time students for the costs of learning. The current system requires part time students to pay upfront. This puts people off from studying part time and it stops innovation in courses that combine work and study. In our proposal the upfront costs for part time students will be eliminated, so that a wider range of people can access higher education in a way that is convenient for them.”

2.5. The 2011 White Paper and the 2012-2013 Reforms

“Our reforms are designed to deliver a more responsive higher education sector in which funding follows the decisions of learners and successful institutions are freed to thrive; in which there is a new focus on the student experience and the quality of teaching and in which [there is]… a diverse range of higher education provision. The overall goal is higher education that is more responsive to student choice, that provides a better student experience and that helps improve social mobility…. we want to ensure that the new student finance regime supports student choice, and that in turn student choice drives competition, including on price”.

“The public money that supports higher education courses should come predominantly in the form of loans to first-time undergraduate students, to take to the institution of their choice, rather than as grants distributed by a central funding council”.

“For the first time, students starting part-time undergraduate courses in 2012/13, many of whom are from non-traditional backgrounds, will be entitled to an up-front loan to meet their tuition costs…This is a major step in terms of opening up access to higher education, and remedies a long-standing injustice in support for adult learners.”

2.6. The 2016 White Paper and the 2017 Higher Education and Research Act

“For competition in the HE sector to deliver the best possible outcomes, students must be able to make informed choices … information, particularly on price and quality, is critical if the higher education market is to perform properly. Without it, providers cannot fully and accurately advertise their offerings, and students cannot make informed decisions… With better information, students will be able to make informed choices about their higher education options and their future careers.”

“By introducing more competition and informed choice into higher education, we will deliver better outcomes and value for students, employers and the taxpayers who underwrite the system. Competition between providers in any market incentivizes them to raise their game, offering consumers a greater choice of more innovative and better quality products and services at lower cost. Higher education is no exception.”

“ensure that the education system for those aged 18 years and over is accessible to all, is supported by a funding system that provides value for money and works for students and taxpayers, incentivizes choice and competition across the sector, and encourages the development of the skills that we need”.

3. Assessment of Proponents’ Claims About The Benefits of Student Choice

3.1. Increasing and Widening Higher Education Participation

3.2. Enhanced Institutional Quality

3.3. Improved Labour Market Responsiveness

3.4. Greater Variety of Provision

4. A Critique of The Student-Choice Concept as Elaborated by Policy Makers

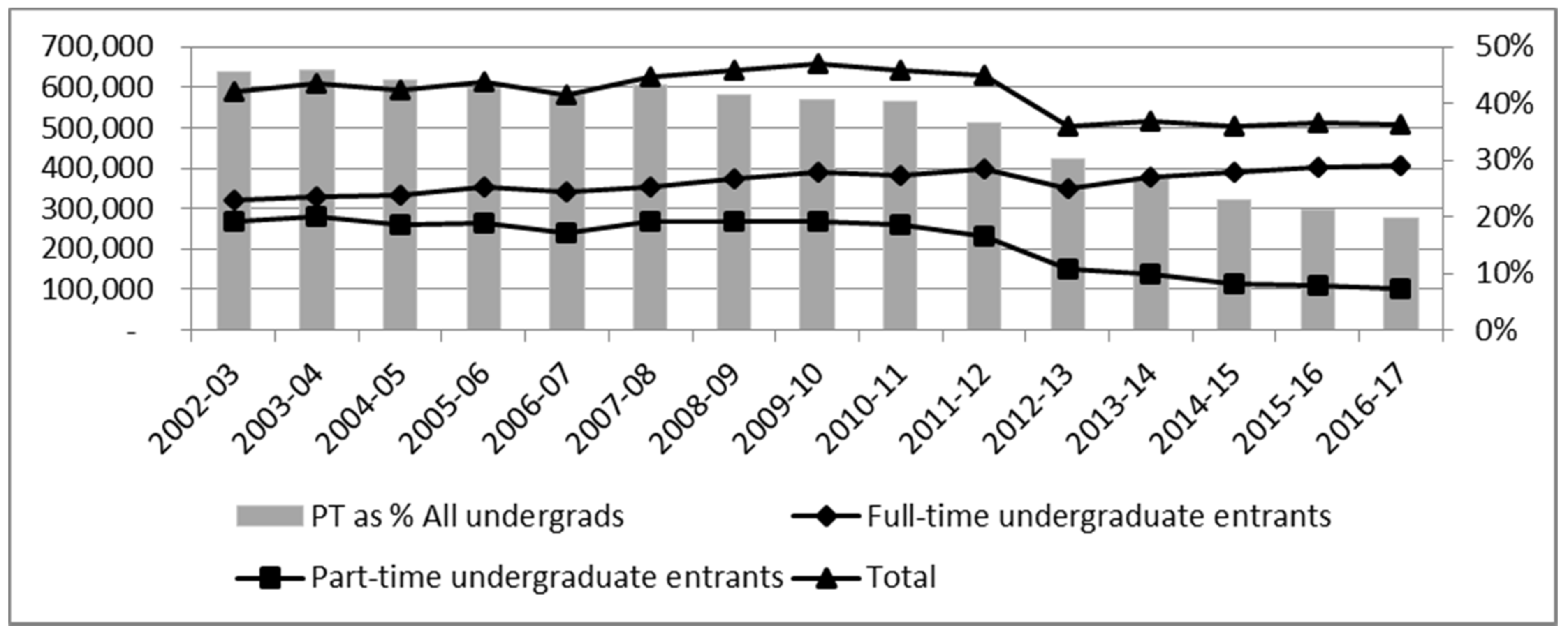

4.1. Explaining the Decline in Enrolments, Especially Among Part-Time Students

4.1.1. The Sharp Rise in Tuition Fees

4.1.2. Difficulty of Part-Timers in Getting Loans

4.2. Explaining the Lack of Reduction in Class Inequality in Access

4.2.1. Insufficient Acknowledgement of Students’ Varying Attitudes toward Debt

4.2.2. A Narrow Conceptualization of Student Choice Making

4.3. Explaining the Lack of Evidence of Better Quality and Greater Labour-Market Responsiveness

4.4. Incorrectly Equating Greater Choice With Greater Equality

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Altbach, Philip. 1999. The logic of mass higher education. Tertiary Education and Management 5: 107–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, Louise, Carole Leathwood, and Merryn Hutchings. 2002. Higher education: A risky business. In Access, Participation, and Higher Education: Policy and Practice. Edited by Annette Hayton and Anna Paczuska. London: Kogan Page. [Google Scholar]

- Arum, Richard, Adam Gamoran, and Yossi Shavit. 2007. More inclusion than diversion: Expansion, differentiation and market structures in higher education. In Stratification in Higher Education: A Comparative Study. Edited by Yossi Shavit, Richard Arum and Adam Gamoran. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ashwin, Paul, Andrea Abbas, and Monica McLean. 2013. Representations of a high-quality system of undergraduate education in English higher education policy documents. Studies in Higher Education 40: 610–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, Thomas R., Shanna Smith Jaggars, and Davis Jenkins. 2015. Redesigning America’s Community Colleges: A Clearer Path to Student Success. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, Ronald. 2013. The end of mystery and the perils of explicitness. In Browne and Beyond: Modernizing English Higher Education. Edited by Claire Callender and Peter Scott. London: Institute of Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bathmaker, Ann-Marie, Nicola Ingram, and Richard Waller. 2013. Higher education, social class, and the mobilization of capitals: Recognising and playing the game. British Journal of Sociology of Education 34: 723–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Ulrich. 1992. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. Los Angeles: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- BIS (Department for Business, Innovation and Skills). 2011. Higher Education: Students at the Heart of the System; Cm. 8122; London: Stationery Office.

- BIS (Department for Business, Innovation and Skills). 2016. Success as a Knowledge Economy: Teaching Excellence, Social Mobility and Student Choice; Cm 9258; London: Stationery Office.

- Blackmore, Paul, Richard Blackwell, and Martin Edmondson. 2016. Tackling Wicked Issues: Prestige and Employment Outcomes in the Teaching Excellence Framework. Oxford: Higher Education Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Blunkett, David. 2000. Modernising Higher Education: Facing the Global Challenge. Speech. Paper presented at the University of Greenwich, London, UK, February 15. [Google Scholar]

- Boliver, Vikki. 2011. Expansion, differentiation, and the persistence of social class inequalities in British higher education. Higher Education 61: 229–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boliver, Vikki. 2013. How fair is access to more prestigious UK universities? British Journal of Sociology 64: 344–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boliver, Vikki. 2015. Lies, damned lies and statistics on widening access to Russell Group universities. Radical Statistics 113: 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, Paul. 2018. Student Loan Statistics. Briefing Paper No. 1079. London: House of Commons Library. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Britton, Jack, Lorraine Dearden, Neil Shephard, and Anna Vignoles. 2016. How English Domiciled Graduate Earnings Vary with Gender, Institution Attended, Subject and Socio-Economic Background. IFS Working Paper W16/06. London, UK: Institute for Fiscal Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Phillip. 2013. Education, opportunity and the prospects for social mobility. British Journal of Sociology of Education 34: 5–6, 678–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Roger. 2012. The myth of student choice. Vistas: Education, Economy, and Community 2: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Roger. 2013. Everything for Sale? The Marketization of UK Higher Education. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Roger. 2015. The marketization of higher education: Issues and ironies. New Vistas 1: 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Roger. 2018. Neoliberalism, Marketisation and Higher Education: How Neoliberalism is Reshaping the Provision of English Higher Education. Professorial lecture at the University of West London, London, UK, February 27; Available online: https://www.uwl.ac.uk/visit-us/public-lectures/lecture-series/neoliberalism-marketisation-and-higher-education (accessed on 30 July 2018).

- Burgess, Simon. 2016. Human Capital and Education: The State of the Art in the Economics of Education. IZA Discussion Paper No. 9885. Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA). [Google Scholar]

- Callender, Claire. 2013. Part-time undergraduate student funding and financial support. In Browne and Beyond: Modernizing English Higher Education. Edited by C. Callender and P. Scott. London: Bedford Papers, pp. 130–58. [Google Scholar]

- Callender, Claire, and Jonathan Jackson. 2005. Does fear of debt deter students from HE? Journal of Social Policy 34: 509–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callender, Claire, and Geoff Mason. 2017. Does student loan debt deter participation in higher education? New evidence from England. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences 671: 20–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callender, Claire, and John Thompson. 2018. The Lost Part-Timers: The Decline of Part-Time Undergraduate Higher Education in England. London: Sutton Trust. Available online: https://www.suttontrust.com/research-paper/lost-part-timers-mature-students/ (accessed on 30 July 2018).

- Cappelen, Alexander. W., Sebastian Fest, Erik O. Sorensen, and Bertil Tungodden. 2013. Choice and over-attribution of individual responsibility. Paper presented at the CESifo Area Conference on Behavioural Economics, Munich, Germany, October 25–26. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Randall. 1979. The Credential Society. New York: Seminar Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Peter. 2012. Can governments improve higher education through “informing choice”? British Journal of Educational Studies 60: 261–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearden, Lorraine, Emla Fitzsimons, and Gill Wyness. 2010. The Impact of Higher Education Finance on University Participation in the UK; BIS Research Paper 11; London: Department for Business Innovation and Skills.

- Dearden, Lorraine, Alissa Goodman, and Gill Wyness. 2012. Higher education finance in the UK. Fiscal Studies 33: 73–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearden, Lorraine, Emla Fitzsimons, and Gill Wyness. 2014. Money for nothing: Estimating the impact of student aid on participation in higher education. Economics of Education Review 43: 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deem, Rosemary. 2001. Globalisation, new managerialism, academic capitalism and entrepreurialism in universities: is the local dimension still important? Comparative Education 37: 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Trade and Industry. 1998. Our Competitive Future: Building the Knowledge Driven Economy; London: Department of Trade and Industry. Available online: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http://www.dti.gov.uk/comp/competitive/wh_int1.htm (accessed on 30 July 2018).

- Deutschlander, D. 2017. Academic undermatch: How general and specific cultural capital structure inequality. Sociological Forum 32: 162–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, Fiona. 1998. Class analysis and the stability of class relations. Sociology 32: 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, Fiona. 2004. Class Practices: How Parents Help Their Children Get Good Jobs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- DfE. 2018a. Review of Post-18 Education and Funding: Terms of Reference; London: Department for Education. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/682348/Post_18_review_-_ToR.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2018).

- DfE. 2018b. Graduate outcomes (LEO): Employment and Earnings Outcomes of Higher Education Graduates by Subject Studied and Graduate Characteristics; SFR 15/2018; London: Department for Education. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/.../SFR15_2018_Main_text.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2018).

- DFEE. 1998. Blunkett Welcomes Teaching and Higher Education Act; Press Release. London: Department for Education and Employment, July 17.

- DfES (Department for Education and Skills). 2003. The Future of Higher Education. Cm. 5735. London: Stationery Office. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, Abigail, Tim Vorley, Jennifer Roberts, and Stephen Jones. 2012. Behavioural Approaches to Understanding Student Choice. Leicester: CFE Research. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, Abigail, Jennifer Roberts, Tim Vorley, Guy Birkin, James Evans, Jonathan Sheen, and Tej Nathwani. 2014. UK Review of the Provision of Information about Higher Education: Advisory Study and Literature Review. Leicester: CFE Research. Available online: http://www.hefce.ac.uk/media/hefce/content/pubs/indirreports/2014/Provision,of,information,advisory,study,and,literature,review/2014_infoadvisory.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2018).

- Dill, David D. 2007. Will market competition assure academic quality? An analysis of the UK and US experience. In Quality Assurance in Higher Education: Trends in Regulation, Translation and Transformation. Edited by Don Westerheijden. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Dorsett, Richard, Silvia Lui, and Martin Weale. 2010. Economic Benefits of Lifelong Learning. Discussion Paper No 352. London: National Institute of Economic and Social Research. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty, Kevin J. 2018. Higher Education Choice-Making in the United States: Freedom, Inequality, Legitimation. Working Paper No 35. London, UK: Centre for Global Higher Education, UCL Institute of Education. Available online: http://www.researchcghe.org/publications/higher-education-choice-making-in-the-united-states-freedom-inequality-legitimation (accessed on 24 July 2018).

- Dougherty, Kevin J., and Claire Callender. 2017. English and American Higher Education Access and Completion Policy Regimes: Similarities, Differences, and Possible Lessons. Working Paper #24. London, UK: Centre for Global Higher Education, UCL Institute of Education, University of London. Available online: http://www.researchcghe.org/publications/english-and-american-higher-education-access-and-completion-policy-regimes-similarities-differences-and-possible-lessons (accessed on 24 July 2018).

- Dougherty, Kevin J., Hana Lahr, and Vanessa S. Morest. 2017. Reforming the American Community College: Promising Changes and Their Challenges. New York: Community College Research Center, Teachers College, Columbia University. Available online: https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/media/k2/attachments/reforming-american-community-college-promising-changes-challenges.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2018).

- Dynarski, Susan. 2003. Does aid matter? Measuring the effect of student aid on college attendance and completion. American Economic Review 93: 279–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dynarski, Susan, and Judith Scott-Clayton. 2013. Financial aid policy: Lessons from research. Future of Children 23: 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, Peter, and Kate Purcell. 2013. Classifying Graduate Occupations for the Knowledge Society. Futuretrack Working Paper 5. Coventry, UK: Institute for Employment Research, University of Warwick. [Google Scholar]

- Feigenbaum, Harvey, Jeffrey Henig, and Chris Hamnett. 1998. Shrinking the State: The Political Underpinnings of Privatization. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth, Alasdair, and Andy Furlong. 2003. Socio-Economic Disadvantage and Access to Higher Education. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, Graham. 2012. Implications of ‘Dimensions of Quality’ in a Market Environment. York: Higher Education Academy. [Google Scholar]

- Goldthorpe, John M. 1996. Class analysis and the reorientation of class theory: The case of persisting differentials in educational attainment. British Journal of Sociology 47: 481–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Francis, and Golo Henseke. 2016. The changing graduate labour market: Analysis using a new indicator of graduate jobs. IZA Journal of Labor Policy 5: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Francis, and Yu Zhu. 2010. Overqualification, job dissatisfaction, and increasing dispersion in the returns to graduate education. Oxford Economic Papers 62: 740–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, Vicky, and Anna Fisk. 2013. Considering Teaching Excellence in Higher Education: 2007–2013. York: Higher Education Academy. [Google Scholar]

- Gyimah, Sam. 2018. Delivering value for money in the age of the student. Speech. Paper presented at the HEPI Annual Conference, London, UK, June 7; Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/delivering-value-for-money-in-the-age-of-the-student (accessed on 31 July 2018).

- Harvey, David. 2005. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher, Richard. 1998. Class differentiation in education: Rational choices? British Journal of Sociology of Education 19: 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazelkorn, Ellen, Hamish Coates, and Alexander C. McCormick. 2018. Research Handbook on Quality, Performance, and Accountability in Higher Education. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- HEFCE. 2014a. UK Review of the Provision of Information about Higher Education. Data for National Student Survey Results and Trends Analysis 2005–2013. Available online: http://www.hefce.ac.uk/data/year/2014/nsstrends/ (accessed on 23 July 2018).

- HEFCE. 2014b. Pressure from All Sides: Economic and Policy Influences on Part-Time Higher Education. HEFCE Report 2014/8d. Bristol: Higher Education Funding Council for England. [Google Scholar]

- HEFCE. 2015. Higher Education in England 2015 Key Facts. Available online: www.hefce.ac.uk/.../Analysis/HE,in,England/HE_in_England_2015.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2018).

- HEFCE. 2016. Student Characteristics. Available online: http://www.hefce.ac.uk/analysis/HEinEngland/students/social/ (accessed on 19 July 2018).

- HEFCE. 2018. Higher Education in England: Undergraduate Education. Available online: http://www.hefce.ac.uk/analysis/HEinEngland/undergraduate/ (accessed on 19 July 2018).

- HESA. 2011a. UK Performance Indicators 2010/11 Widening Participation. Available online: https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/performance-indicators/releases/2010-11-widening-participation (accessed on 19 July 2018).

- HESA. 2011b. Destinations of Leavers From Higher Education in the United Kingdom for the Academic Year 2009/10, statistical First Release SFR162. Available online: https://www.hesa.ac.uk/news/30-06-2011/sfr162-destinations-of-leavers (accessed on 19 July 2018).

- HESA. 2017. Destinations of Leavers from Gigher Education in the United Kingdom for the Academic Year 2009/10, statistical First Release, SFR 245. Available online: https://www.hesa.ac.uk/news/29-06-2017/sfr245-destinations-of-leavers (accessed on 19 July 2018).

- HESA. 2018a. Summary—UK Performance Indicators 2015/16. Available online: https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/performance-indicators/summary/2015-16 (accessed on 19 July 2018).

- HESA. 2018b. Non-Continuation Summary: UK Performance Indicators 2016/17. Available online: https://www.hesa.ac.uk/news/08-03-2018/non-continuation-summary (accessed on 31 July 2018).

- House of Commons. 2010. Hansard 3 Nov 2010: Column 924. Available online: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201011/cmhansrd/cm101103/debtext/101103-0001.htm#10110358000003 (accessed on 31 July 2018).

- House of Commons, Committee of Public Accounts. 2018. The Higher Education Market; London: Author.

- Hutchings, Merryn. 2003. Information, advice, and cultural discourses of higher education. In Higher Education and Social Class. Edited by Louise Archer, Merryn Hutchings and Alistair Ross. London: Routledge Falmer. [Google Scholar]

- IRHEFSF (Independent Review of Higher Education Funding and Student Finance). 2010. Securing a Sustainable Future for Higher Education: An Independent Review of Higher Education Funding and Student Finance. Available online: http://www.independent.gov.uk/browne-report (accessed on 12 October 2010).

- Jerrim, John, Anna K. Chmielewskib, and Phil Parker. 2015. Socioeconomic inequality in access to high-status colleges: A cross-country comparison. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 42: 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Steven. 2016. Expressions of student debt aversion and tolerance among academically able young people in low-participation English schools. British Educational Research Journal 42: 277–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labaree, D. 2012. Someone Has to Fail. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Land, Ray, and George Gordon. 2013. Enhancing Quality in Higher Education: International Perspectives. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 259–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lareau, A., and A. Cox. 2011. Social class and the transition to adulthood. In Social Class and Changing Families in an Unequal America. Edited by M. Carlson and P. England. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 134–64. [Google Scholar]

- Le Grand, Julian. 2007. The Other Invisible Hand: Delivering Public Services Through Choice and Competition. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leathwood, Carolyn, and Merryn Hutchings. 2003. Entry routes to higher education: Pathways, qualifications, and social class. In Higher Education and Social Class. Edited by Louise Archer, Merryn Hutchings and Alistair Ross. London: Routledge Falmer, pp. 137–54. [Google Scholar]

- LFS (Labour Force Survey). 2017. Graduates in the UK Labour Market: 2017; London: Office for National Statistics. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/articles/graduatesintheuklabourmarket/2017#graduates-and-non-graduates-in-work (accessed on 23 July 2018).

- Mangan, Jean, Amanda Hughes, Peter Davies, and Kim Slack. 2010. Fair access, achievement, and geography: Explaining the association between social class and students’ choice of university. Studies in Higher Education 35: 335–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marginson, Simon. 2009. The Limits of Market Reform in Higher Education. Hiroshima: Research Institute for Higher Education, Hiroshima University. Melbourne: University of Melbourne. Available online: http://www.cshe.unimelb.edu.au/people/marginson_docs/RIHE_17Aug09_paper.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2018).

- Marginson, Simon. 2016a. High participation systems of higher education. The Journal of Higher Education 87: 243–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marginson, Simon. 2016b. The worldwide trend to high participation higher education: Dynamics of social stratification in inclusive systems. Higher Education 72: 413–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, Hazel R., and Barry Schwarz. 2010. Does choice mean freedom and well-being? Journal of Consumer Research 37: 344–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, Katherine, and David Karen. 2009. Reproduction, redemption, and respect: Analysis. In Ain’t No Making It, 3rd ed. Edited by Jay MacLeod. Boulder: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mullen, Ann. 2010. Degrees of Inequality. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, Richard, Judith Scott-Clayton, and Gillian Wyness. 2017. The End of Free College in England: Implications for Quality, Enrolments, and Equity. Working Paper No. 30. London, UK: Centre for Global Higher Education, UCL Institute of Education. Available online: http://www.researchcghe.org/publications/the-end-of-free-college-in-england-implications-for-quality-enrolments-and-equity/ (accessed on 30 July 2018).

- Naidoo, R. 2016. Choice in the learning market: Tokenistic ritual or democratic education? In Dimensions of Marketisation in Gigher Education. Edited by Peter John and Joelle Fanghanel. London: Routledge, pp. 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Naidoo, Rajani, Avi Shankar, and Ekant Veer. 2011. The consumerist turn in higher education policy: Policy aspirations and outcomes. Journal of Marketing Management 27: 1142–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Audit Office. 2017. The Higher Education Market. London: Author. Available online: https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/The-higher-education-market.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2018).

- NCIHE—National Committee of Inquiry into Higher Education. 1997. Higher Education in the Learning Society. London: HMSO. [Google Scholar]

- OfS. 2018a. What is the TEF? Available online: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/teaching/what-is-the-tef/ (accessed on 19 July 2018).

- OfS. 2018b. National Student Survey Results 2018. Available online: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/student-information-and-data/national-student-survey-nss/get-the-nss-data/ (accessed on 30 July 2018).

- Olssen, Mark, and Michael A. Peters. 2005. Neoliberalism, higher education and the knowledge economy: From the free market to knowledge capitalism. Journal of Education Policy 20: 313–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perna, Laura. 2006. Studying college choice: A proposed conceptual model. In Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research. Edited by John C. Smart. Dordrecht: Springer, vol. 21, pp. 99–157. [Google Scholar]

- Perna, Laura. 2008. Understanding high school students’ willingness to borrow to pay college prices. Research in Higher Education 49: 589–606. [Google Scholar]

- Plikuhn, Mari, and Matthew Knoester. 2016. A foot in two worlds. In The 2orking Classes and Higher Education: Inequality of Access, Opportunity and Outcome. Edited by Amy E. Stich and Carrie Freie. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, Emma, Will Hunt, Jim Hillage, Emma Drever, Jenny Chanfreau, Steven Coutinho, and Eloise Poole. 2013. Student Income and Expenditure Survey 2011/12; BIS Research Paper No. 115; London: Department for Business, Innovation and Skills.

- Ramsden, Paul, and Claire Callender. 2014. Review of the National Student Survey: Literature Review. Bristol: HEFCE. Available online: http://www.hefce.ac.uk/pubs/rereports/year/2014/nssreview/ (accessed on 22 July 2018).

- Read, Barbara, Louise Archer, and Carole Leathwood. 2003. Challenging cultures? Student conceptions of “belonging” and “isolation” at a post-1992 university. Studies in Higher Education 28: 261–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay, Diane. 2001. Finding or losing yourself? Working-class relationships to education. Journal of Education Policy 16: 333–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay, Diane. 2005. Beyond consciousness? The psychic landscape of social class. Sociology 39: 911–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay, Diane, Miriam E. David, and Stephen Ball. 2005. Degrees of Choice: Class, Race, Gender and Higher Education. Stoke on Trent: Trentham. [Google Scholar]

- Reay, Diane, Gill Crozier, and John Clayton. 2010. ‘Fitting in’ or ‘standing out’: Working class students in UK higher education. British Educational Research Journal 36: 107–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, James, Regina Deil-Amen, and Ann E. Person. 2006. After Admission: From College Access to College Success. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Savani, Krishna, and Aneeta Rattan. 2012. A choice mind-set increases the acceptance and maintenance of wealth inequality. Psychological Science 23: 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savani, Krishna, Nicole M. Stephens, and Hazel R. Markus. 2011. The unanticipated interpersonal and societal consequences of choice: Victim blaming and reduced support for the public good. Psychological Science 22: 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savitsky, Kenneth, Victoria H. Medvec, and Thomas Gilovich. 1997. Remembering and regretting: The Zeigarnik effect and the cognitive availability of regrettable actions and inactions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 23: 248–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott-Clayton, Judith. 2016. Early Labor Market and Debt Outcomes for Bachelor’s Degree Recipients: Heterogeneity by Institution Type and Major, and Trends Over time. New York: Columbia University, Teachers College, Community College Research Center, Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment. Available online: https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/early-labor-market-debt-outcomes-bachelors-recipients.html (accessed on 30 July 2018).

- Slack, Kim, Jean Mangan, Amanda Hughes, and Peter Davies. 2014. “Hot,” “cold,” and “warm” information and higher education decision making. British Journal of Sociology of Education 35: 214–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaughter, Sheila, and Gary Rhoades. 2004. Academic Capitalism and the New Economy: Markets, States, and Higher Education. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter, Sheila, and Gary Rhoades. 2016. State and markets in higher education. In American Higher Education in the 21st Century. Edited by M. Bastedo, P. M. Altbach and P. Gumport. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 503–40. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Jonathan, Matea Pender, and Jessica Howell. 2013. The full extent of student-college academic undermatch. Economic of Education Review 32: 247–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, Nicole M., and Cynthia S. Levine. 2011. Opting out or denying discrimination: How the framework of free choice in American society influences perceptions of gender inequality. Psychological Science 22: 1231–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stich, Amy E., and Carrie Freie. 2016. The Working Classes and Gigher Education: Inequality of Access, Opportunity and Outcome. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Student Loans Company. 2017. Student Support for Higher Education in England 2017: 2016/17 Payments, 2017/18 Awards. Statistical First Release 05/2017. Glasgow: Student Loans Company. Available online: https://www.slc.co.uk/media/9579/slcsfr052017.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2018).

- Thaler, Richard H., Cass Sunstein, and John P. Balz. 2013. Choice architecture. In Behavioral Foundations of Public Policy. Edited by Eldar Shafir. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, John, and Bahram Bekhradnia. 2013. The Impact on Demand of the Government’s Reforms of Higher Education: The First Evidence on Part-Time Demand and an Update on Fulltime. HEPI Report 62. Oxford: Higher Education Policy Institute. Available online: http://www.hepi.ac.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2014/02/HEPI-Report-62-Demand-Report-2013-Full-Report.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2017).

- UCAS. 2017. End of Cycle Report 2017. London: UCAS. Available online: https://www.ucas.com/data-and-analysis/ucas-undergraduate-releases/ucas-undergraduate-analysis-reports/2017-end-cycle-report (accessed on 19 July 2018).

- Vignoles, Anna, and Claire Crawford. 2010. The importance of prior educational experiences. In Improving Learning by Widening Participation in Higher Education. Edited by Miriam David. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Wrosch, Carsten, and Jutta Heckhausen. 2002. Perceived control of life regrets: Good for young and bad for old adults. Psychology and Aging 17: 340–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | The Labour government’s concerns about meeting the demands of a knowledge economy were discussed in detail in a 1998 white paper, Our Competitive Future: Building the Knowledge Driven Economy (Department of Trade and Industry 1998). This white paper was much influenced by publications coming out of the World Bank on the nature of the knowledge economy, the importance of investment in higher education, and the need to substantially privatize it (Olssen and Peters 2005). |

| 2 | When TEF was first introduced, it was anticipated that successful TEF performance would be linked to the level of tuition fees higher education institutions could charge. But this idea been deferred until 2020, in the hope that the evaluative procedures will command greater confidence by then. |

| 3 | This data source is severely limited. First, it only collects data on applications and acceptances to higher education which is different from the actual number of entrants (but it does calculate entry rates). Secondly, it excludes potential part-time students because they do not apply to higher education institutions through UCAS but directly to institutions. Finally, the measures of social disadvantage used primarily apply to young people and consequently the analysis focuses just on young students, especially 18 year olds rather than all full-time students. |

| 4 | These might include staff teaching qualifications, staff research expertise or industrial and business experience, research-informed teaching, and activities and resources to support learning such as investment in specialist equipment, technology and facilities. |

| 5 | These might include curriculum design, development and review, student assessment and feedback, optimisation of retention and progression, industrial engagement and volunteering opportunities, and student partnerships. |

| 6 | However, many criticise the NSS for measuring satisfaction rather than quality. See Ramsden and Callender (2014) for a review of the literature. |

| 7 | Part-time students were only included in the survey later. |

| 8 | There are other limitations to the DLHE and many of these are being addressed in the new Graduate Outcomes survey which will replace the DLHE. |

| 9 | Defined as having left full time education within five years of the survey date. |

| 10 | Because the classifier is fixed for the whole period, it may miss within-occupation upskilling and thus overstate the rise of underemployment. See Green and Henseke (2016). |

| 11 | It provides no data on graduates’ occupation, giving only a partial picture of graduate outcomes. |

| 12 | Non-degree qualifications include: Foundation Degrees (FD), HND and HNC: Other higher education qualifications, for example Certificate of Higher Education; and Institutional Credits—credits that can be aggregated to qualify for a higher education award but which do not constitute an award in their own right. |

| 13 | While noting this, it is important to keep in mind that the main determinant of social-class differences in access to higher education is differentials in academic preparation (Vignoles and Crawford 2010). |

| 14 | In 2015/16, an estimated 89.5 per cent of English undergraduate students took out maintenance loans and 94 per cent of students took out tuition loans (Student Loans Company 2017). |

| 15 | The concept of risk—because it is both a category of individual rational analysis and also a socially constructed and socially variable perception—may provide a very fruitful location for the rapprochement between Goldthorpe’s (1996) rational action theory and Bourdieu’s (1977) concept of habitus that Devine (1998, 2004) and Hatcher (1998) have called for. For more on risk, see the work of Ulrich Beck (1992) on the rise of a “risk society” and its impact on individuals’ self-conceptions. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Callender, C.; Dougherty, K.J. Student Choice in Higher Education—Reducing or Reproducing Social Inequalities? Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100189

Callender C, Dougherty KJ. Student Choice in Higher Education—Reducing or Reproducing Social Inequalities? Social Sciences. 2018; 7(10):189. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100189

Chicago/Turabian StyleCallender, Claire, and Kevin J. Dougherty. 2018. "Student Choice in Higher Education—Reducing or Reproducing Social Inequalities?" Social Sciences 7, no. 10: 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100189

APA StyleCallender, C., & Dougherty, K. J. (2018). Student Choice in Higher Education—Reducing or Reproducing Social Inequalities? Social Sciences, 7(10), 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100189