Discursive Struggle and Agency—Updating the Finnish Peatland Conservation Network

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (a)

- What was the role of different policy discourses and agency in the process of drafting the Supplemental Mire Conservation Programme in Finland?

- (b)

- Which powerful discourses did the agents rely on in order to gain discursive agency and persuade others to support their preferred policy solutions?

- (c)

- How did this influence the outcome of the process?

2. Discursive Agency

3. Case Study, Materials and Methods

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. The Discourses of Mire Conservation

“The biodiversity indicators of Finnish nature, […] conditions that can not be reduced to endangered nature types and endangered single species, […] these indicators are alarmingly red,which meansmire biodiversity is declining. So this is basically the scientific fact that many stakeholders have systematically emphasized”.(Interview 4 Natur och Miljö—Swedish speaking nature conservation association of Finland)

“It is crystal clear for us that there isa need for this type of nature conservation planning,the so-called conventional nature conservation which is approved by the Council of State”.(Interview 4 Natur och Miljö—Swedish speaking nature conservation association of Finland)

“That type of symmetryor equilibrium and action that allows the development ofthe bioeconomy asa leading economic activity in Finland, which is based on sustainable natural resources and sustainable use of them,and which isa state-of-the-art activityin Finland compared to many other nations. And in this regard we should reconsider the nature conservation issue, not only as an ideology, but in practice and being realistic”.(Interview 8 Finnish Forest Industries)

“I think that talk is increasing that there has to be local support to these[…] nature values and biodiversity”.(Interview 1)

“A model that could be applied, would be to find out what arethe most important mires for conservation and then to market voluntary conservation for landownersin those areas, that there would be compensation. We can negotiate higher compensation and then, if the area is under conservation, the recreational uses should not be restricted unnecessarily. And another important thing is to reserve enough resources for peatland restoration”.(Interview 3 Finnish Wildlife Agency)

4.2. The Outcome

“This change of assignment wasclearly brought in by politicaldirection and where those politics camefrom, there has to have beena group of political forces that wanted topush towards voluntary conservation instead of the nature conservation program according to theNatureConservationAct”.(Interview 12)

4.3. The Feedback

“the value of peatland is connected to which point of view is used and who is thinking about the issue”.(Interview 12)

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Background Organization of the Interview Respondents

References

- Åkerman, Maria, and Taru Peltola. 2002. Temporal scales and environmental knowledge production. Landscape and Urban Planning 61: 147–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanen, Aulikki, and Kaisu Aapala. 2015. Proposal of the Mire Conservation Group for Supplemental Mire Conservation. Reports of the Ministry of the Environment 26/2015. Helsinki: Ympäristöministeriö. 175p. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, Eerika, and Outi Ratamäki. 2016. Effective arguments for ecosystem services in biodiversity conservation—A case study on Finnish peatland conservation. Ecosystem Services 22: 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostopolou, Evangelia, Dimitrios Bormpoudakis, Riikka Paloniemi, Joanna Cent, Malgorzata Grodzińska-Jurczak, Agata Pietrzyk-Kaszyńska, and John Pantis. 2014. Governance rescaling and the neoliberatization of nature: The case of biodiversity conservation in four EU countries. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 21: 1745–2627. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, Riikka, and Riikka Paloniemi. 2012. Deliberation in cooperative networks for forest conservation. Journal of Integrative Environmental Sciences 9: 151–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busca, Didier, and Nathalie Lewis. 2015. The territorialization of environmental governance. Governing the environment based on just inequalities? Environmental Sociology 1: 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, Martin B., and Vivien A. Schmidt. 2016. Power through, over and in ideas: conceptualizing ideational power in discursive institutionalism. Journal of European Public Policy 23: 1466–4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Kai M. A., Satterfield Terre, and Joshua Goldstein. 2012. Rethinking ecosystem services to better address and navigate cultural values. Ecological Economics 74: 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryzek, John S. 1990. Discursive Democracy. Politics, Policy and Political Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 254p. [Google Scholar]

- Dryzek, John S. 2013. The Politics of the Earth. Environmental Discourses, 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 270p. [Google Scholar]

- Dryzek, John S., and Carolyn M. Hendriks. 2012. Fostering deliberation in the forum and beyond. The argumentative turn revisited. In Public Policy as a Communicative Practice. Edited by Frank Fischer and Herbert Gottweis. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 31–57. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, Norman. 1993. Critical discourse analysis and the marketization of public discourse: The universities. Discourse & Society 4: 133–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, Norman. 2010. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language, 2nd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited. 608p. [Google Scholar]

- Finnish Council of State. 2012. The Records of the Preparatory Project in the Finnish Council of State Project Register: YM027:00/2012. Available online: http://valtioneuvosto.fi/hanke?selectedProjectId=3160 (accessed on 18 May 2016).

- Fischer, Frank. 2000. Citizens, Experts and the Environment: The Politics of Local Knowlegde. Durham: Duke University Press. 351p. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Frank, and John Forester. 1993. The Argumentative Turn in Policy Analysis and Planning. Durham: Duke University Press. 327p. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Frank, and Herbert Gottweis. 2012. Introduction: The argumentative turn revisited. In The Argumentative Turn Revisited. Public Policy as a Communicative Practice. Edited by Frank Fischer and Herbert Gottweis. Durham and London: Duke University Press, pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Baggethun, Erik, and Roldan Muradian. 2015. In markets we trust? Setting the boundaries of market-based instruments in ecosystem services governance. Ecological Economics 117: 217–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajer, Maarten A. 1995. The Politics of Environmental Discourse: Ecological Modernizations and the Policy Process. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 345p. [Google Scholar]

- Hajer, Maarten A. 2005. Rebuilding Ground Zero. The politics of performance. Planning Theory & Practice 6: 445–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hajer, Maarten, and Wytske Versteeg. 2005. A Decade of Discourse Analysis of Environmental Politics: Achievements, Challenges, Perspectives. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning 7: 175–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, Jean. 2004. Case study research. In Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research. Edited by C. Cassell and G. Symon. London: Sage Publications, pp. 323–33. [Google Scholar]

- Helsingin Sanomat. 2014. Grahn-Laasonen: We Will Soon Get Back to the Measures of Mire Conservation. Contestations Resurfaced in the Mire Day of the Minister of the Environment. Available online: http://www.hs.fi/politiikka (accessed on 8 January 2015).

- Hendriks, Carolyn M. 2005. Participatory storylines and their influence on deliberative forums. Policy Sciences 38: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiedanpää, Juha. 2002. European wide conservation versus local well-being: The reception of the Natura 2000 reserve network in Karvia, SW-Finland. Landscape and Urban Planning 61: 113–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiedanpää, Juha. 2005. The edges of conflict and consensus: A case for creativity in regional forest policy in southwest Finland. Ecological Economics 55: 485–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, David. 2010. Power, discourse, and policy: Articulating a hegemony approach to critical policy studies. Critical Policy Studies 3: 318–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joosten, Hans, Marja-Liisa Tapio-Biström, and Susanna Tol, eds. 2012. Peatlands—Guidance for Climate Change Mitigation through Conservation, Rehabilitation and Sustainable Use. Rome: FAO and Wetlands International. 100p. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, Andrew, Wurzel Rüdiger, and Anthony Zito, eds. 2003. ‘New’ Instruments of Environmental Governance: National Experiences and Prospects. London: Frank Cass. [Google Scholar]

- Kaakinen, Eero, and Pekka Salminen. 2006. Mire conservation and its short history in finland. In Finland-Land of Mires. The Finnish Environment 23/2006. Edited by Tapio Lindholm and Raimo Heikkilä. Vammala: Vammalan Kirjapaino, pp. 229–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kallis, Giorgos, Erik Gómez-Baggethun, and Christos Zografos. 2013. To value or not to value? That is not the question. Ecological Economics 94: 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareksela, Santtu, Atte Moilanen, Seppo Tuominen, and Janne Kotiaho. 2013. Use of inverse spatial conservation prioritization to avoid biological diversity loss outside protected areas. Conservation Biology 27: 1294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laclau, Ernesto, and Chantal Mouffe. 1985. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Leipold, Sina, and Georg Winkel. 2016a. Discursive agency: (Re-)conceptualizing actors and practices in the analysis of discursive policymaking. The Policy Studies Journal 45: 510–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leipold, Sina, and Georg Winkel. 2016b. Divide and conquer—Discursive agency in the politics of illegal logging in the United States. Global Environmental Change 36: 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukkarinen, Jani, and Teijo Rytteri. 2016. The Carbon Sinks of Finnish Forests and the Politics of Scale. [Suomen metsien hiilinielut ja skaalojen politiikka]. Alue ja Ympäristö 1: 80–94. [Google Scholar]

- Maaseudun Tulevaisuus. 2014. The Landowner Must Be Able to Play Lotto Before the Winning Ticket. [Maanomistajan pitää pystyä lottoamaan ennen voittoa]. Available online: http://www.maaseuduntulevaisuus.fi/politiikka-ja-talous/maanomista (accessed on 8 January 2015).

- Matulis, Brett S., and Jessica R. Moyer. 2016. Beyond inclusive conservation: The value of pluralism, the need for agonism, and the case for social instrumentalism. Conservation Letters 10: 279–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of the Environment. 2014. The Possibilities for Voluntary Conservation Will Be Investigated. [Mahdollisuudet vapaaehtoiseen suojeluun selvitetään]. (Press release). Available online: http://www.ym.fi/fi-FI/Ajankohtaista/Tiedotteet/Mahdollisuudet_va (accessed on 8 January 2015).

- Mol, Arthur P. J. 2014. The lost innocence of transparency in environmental politics. In Transparency in Global Environmental Governance: Critical Perspectives. Edited by A. Gupta and M. Mason. Cambridge: The MIT Press, pp. 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- MTK. 2014. Significant Conservation act by the Environmental Minister Grahn-Laasonen. [Merkittävä suojeluteko ympäristöministeri Grahn-Laasoselta]. (Press release). Available online: http://www.mtk.fi/ajankohtaista/tiedotteet/tiedotteet_2014/lokakuu/fi (accessed on 8 January 2015).

- O’Riordan, Margaret, Marie Mahon, and John Mc Donagh. 2015. Power, discourse and participation in nature conflicts: The case of turf cutters in the governance of Ireland’s raised bog designations. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning 17: 127–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, Markku, and Anne Kumpula. 2008. Voluntariness and forcedness in nature conservation. Legal and ethical considerations. Tiede & Edistys 33: 273–92. [Google Scholar]

- Paloniemi, Riikka, and Vilja Vilja. 2009. Changing ecological and cultural states and preferences of nature conservation: The case study of nature values trade in South-Western Finland. Journal of Rural Studies 25: 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primmer, Eeva, Riikka Paloniemi, Jukka Similä, and David N. Barton. 2013. Evolution in Finland’s Forest Biodiversity Conservation Payments and the Institutional Constraints on Establishing New Policy. Society & Natural Resources 26: 1137–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rydin, Yvonne. 2003. Conflict, Consensus and Rationality in Environmental Planning: An Institutional Discourse Approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 200p. [Google Scholar]

- Rytteri, Teijo, and Jarmo Kortelainen. 2015. Path dependence of forest sector and limits of energy use of forests. Politiikka 57: 18–32. [Google Scholar]

- Saarikoski, Heli, Maria Åkerman, and Eeva Primmer. 2012. The Challenge of Governance in Regional Forest Planning: An Analysis of Participatory Forest Program Processes in Finland. Society and Natural Resources 25: 667–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomaa, Anna, Riikka Paloniemi, Teppo Hujala, Salla Rantala, Anni Arponen, and Jari Niemelä. 2016. The use of knowlegde in evidence-informed voluntary conservation of Finnish forests. Forest Policy and Economics 73: 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppä, Heikki. 2002. Mires of Finland: Regional and local controls of vegetation, landforms, and long-term dynamics. Fennia 180: 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, Eva, and Jacob Torfing. 2016. Introduction. Governance Network Research. Towards a Second Generation. In Theories of Democratic Network Governance. Edited by Eva Sørensen and Jacob Torfing. Basingstoke Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, Deborah. 2002. Policy Paradox: The Art of Political Decision Making, 2nd ed. New York: W. W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Takala, Tuomo, Teppo Hujala, Minna Tanskanen, and Jukka Tikkanen. 2017. The order of forest owners’ discourses: Hegemonic and marginalized truths about the forest and forest ownership. Journal of Rural Studies 55: 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallis, Heather, and Jane Lubchenco. 2014. Working together: A call for inclusive conservation. Nature 515: 27–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teräväinen, Tuula. 2010. Political opportunities and storylines in Finnish climate policy negotiations. Environmental Politics 19: 196–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnhout, Esther, Jelle Behagel, Francesca Ferranti, and Raoul Beunen. 2015. The construction of legitimacy in European nature policy: Expertise and participation in the service of cost-effectiveness. Environmental Politics 24: 461–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainio, Annukka, and Riikka Paloniemi. 2013. Adapting to the gender order: Voluntary conservation by forest owners in Finland. Land Use Policy 35: 247–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Robert K. 2003. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. London: Sage Publications. 181p. [Google Scholar]

- Yle. 2014. Sanni Grahn-Laasonen Steps in as a New Minister of the Environment. [Sanni Grahn-Laasonen nousee uudeksi ympäristöministeriksi]. Available online: http://yle.fi/uutiset/sanni_grahn-laasonen (accessed on 4 April 2016).

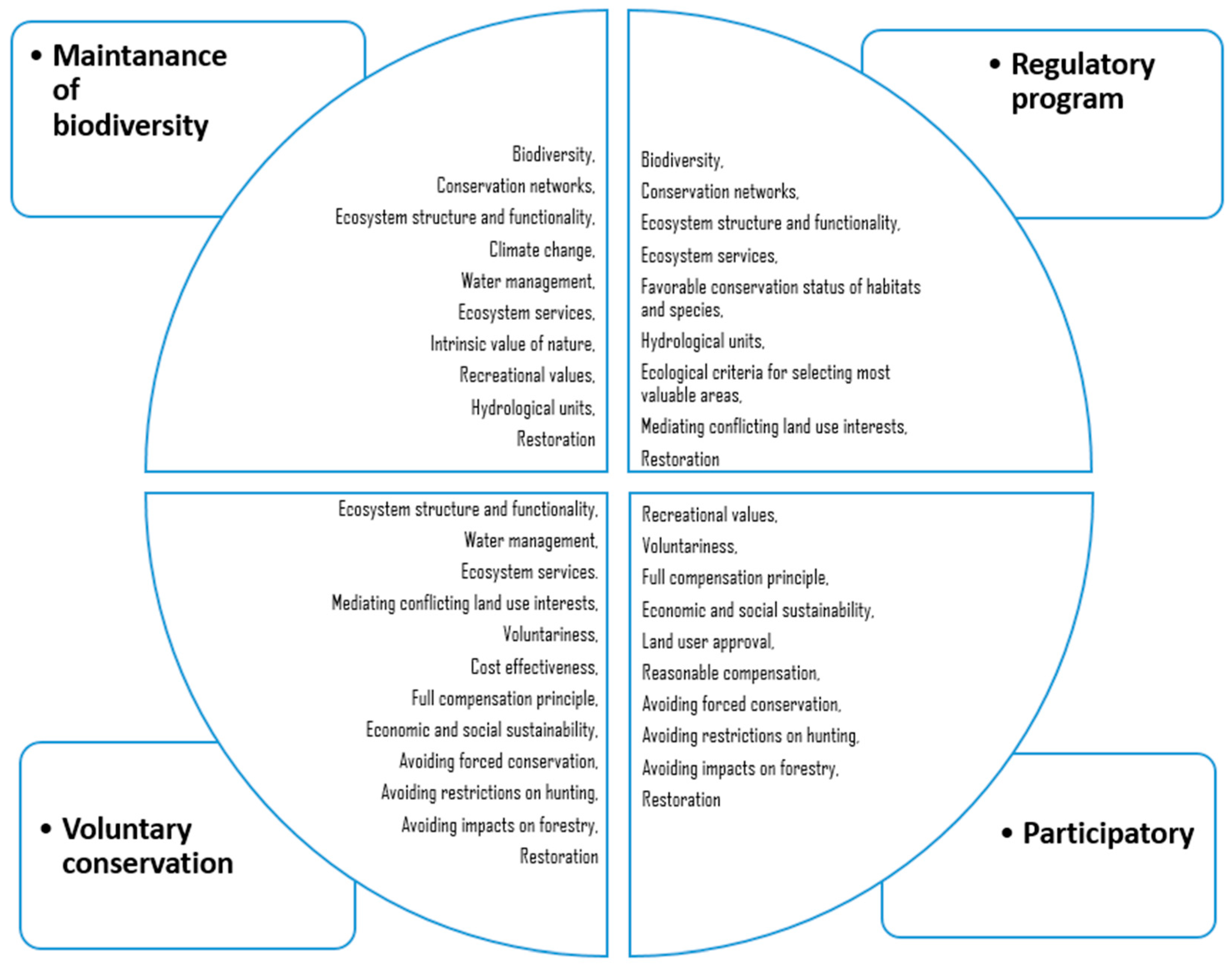

| Comments on the Proposal | Maintanance of Biodiversity | Regulatory Program | Voluntary Conservation | Participatory |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfied/dissatisfied with the proposal | Dissatisfied: leads to (un)favorable status of mire conservation | Dissatisfied: Suggested measures do not guarantee favorable conservation status | Satisfied: Interest of tourism and forestry have to be taken into account | Satisfied: No legal effect on land use |

| Openness | The working group was well organized and open | The working group was well organized and open | Co-operation with interest groups | Acceptance of the land owners and forest owners |

| Resources | Sufficient funding has to be guaranteed | Sufficient funding has to be guaranteed | Sufficient resources needed; Cost-effectiveness | Full compensation principle; Direct compensation to landowners |

| Selection of areas | Should be based on nature conservation science, too much reliance on the 100,000 ha guiding the selection of areas | Ecological foundation for the selection criteria of areas; The connectivity of mire areas; hydrology | The bordering areas have to be purchased by the state | - |

| Favored policy measures | Mires have to be protected as hydrological units; METSO not suitable for the conservation of open bogs | Temporary conservation insufficient; METSO not suitable for the conservation of open bogs; Conflicting land use interests have to be consolidated | Voluntary action on private land; Land use planning part of the policy means; Most important areas with forestry use have to be prioritized; No restriction on hunting | Voluntary action; Increasing the knowledge of the importance of conservation through information campaigns; No restriction on hunting |

| Other | Decision on principle of sustainable use and conservation needs to be taken into account | Risks of voluntary conservation not assessed; Few resources for informing landowners and the public | Reduction of bureaucracy | Voluntary land owners can take part in restoration projects |

| Pilot projects | - | Deleloping new measures | Pilot projects | Pilot projects |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Albrecht, E. Discursive Struggle and Agency—Updating the Finnish Peatland Conservation Network. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100177

Albrecht E. Discursive Struggle and Agency—Updating the Finnish Peatland Conservation Network. Social Sciences. 2018; 7(10):177. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100177

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlbrecht, Eerika. 2018. "Discursive Struggle and Agency—Updating the Finnish Peatland Conservation Network" Social Sciences 7, no. 10: 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100177

APA StyleAlbrecht, E. (2018). Discursive Struggle and Agency—Updating the Finnish Peatland Conservation Network. Social Sciences, 7(10), 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100177