Abstract

Individual, micro-level attitudes towards nonprofit organizations (NPOs) can have many potential determinants. In this study, we explore the impact of three categories of potential determinants of attitudes towards NPOs: Political cleavages (the cultural integration vs. demarcation cleavage and the economic integration vs. demarcation cleavage); religiosity and spirituality; and values (the survival vs. self-expression value dimension). Based on a representative survey in Switzerland, we estimate the impact of those factors for five different attitudinal dimensions and six different NPO types. The Bayesian model estimates show that all three categories of determinants have small to moderate impact. The effects of religiosity, spirituality, the self-expression value dimension, and of economic integration are generally positive. The effects of the survival value dimension and of cultural demarcation are generally negative, with the exception of the NPO type of professional associations.

1. Introduction: Where Do Attitudes towards NPOs Come From?

Not all people in a given society care about nonprofit-organizations (NPOs) to the same degree and in the same manner. Trivial though this observation may be, it is not easy to explain: The reasons why people care or do not care about NPOs are not all that obvious. From a general meta-theoretical point of view, one could attempt to embed the question of attitudes towards NPOs in one of three conceptual frameworks.

In a macro-level framework, the relationship between the general population and NPOs can be thought of, for example, as a relationship of demand and supply (Ben-Ner and Gui 2003; Gui 1991). From this perspective, attitudes towards NPOs reflect differential preferences within the population. The closer an NPO matches a person’s utility function, the more positive the attitudes of that person towards that NPO is going to be. Both NPOs and the general population are rational actors within this perspective, meaning that NPOs have their own utility functions that they are trying to realize the best they can, given the preference within the population. From this market-based understanding of NPOs, the genesis of preferences within the population is random noise; what matters is not where preferences come from, but rather how rational actors make decisions based on their preferences. Macro-level theoretical perspectives are not limited to market-based approaches. For example, with a quasi-evolutionary ecological approach (Hannan and Freeman 1977), different kinds of NPOs can be thought of as different populations of NPOs that have different fitness properties with regard to their environment. The environment, in this case, consists of the attitudes of the general population towards NPOs. Again, however, the attitudes towards NPOs within the general population are thought of as, essentially, random noise.

In a meso-level framework, the locus of interest are the specific actions of NPOs as organizations. More specifically: The actions and strategies implemented by NPOs in order to reach and affect the general population or target population(s) within the general population. From this perspective, marketing efforts by NPOs play an important role in reaching stakeholders and in shaping their attitudes (Helmig et al. 2004; Morris et al. 2001; Wymer et al. 2006). There is evidence that marketing efforts, in a broad sense, have an observable impact on how NPOs are perceived within their target population(s) and thus on their performance (Balabanis et al. 1997; Camarero and Garrido 2012; Mainardes et al. 2017; Ranganathan and Henley 2008; White and Simas 2008). Furthermore, given a plethora of evidence from cognitive psychology and behavioral economics (John et al. 2013), we can be reasonably confident that being exposed to information can affect preferences and thus have an impact on attitudes. However, in such a meso-level framework, the actions of NPOs are of central interest and human preferences are essentially conceptualized as a blank canvas that is painted by external stimuli.

Attitudes within the general population are neither just random noise nor are they simply a blank canvas. That is why a micro-level framework of individual traits and motivations as drivers of attitudes towards NPOs provides additional explanatory power. In this study, we adopt just such a perspective.

Micro-Level Traits and Motivations That Shape Attitudes towards NPOs

Micro-level research about attitudes towards NPOs is mostly focused on factors that influence people’s willingness to donate money to and their willingness to volunteer for nonprofit organizations and causes. There is evidence that a number of factors play a role in shaping donation and volunteering willingness. These factors can roughly be grouped into four categories: Socio-demographics, social contexts, personality traits, and attitudinal factors.

The common socio-demographic factors that have been found to have an impact are gender, ethnicity, age, income, and educational background (Schlegelmilch et al. 1997; Wilson 2012; Sargeant 1999; Einolf 2011; Gittell and Tebaldi 2006; Wiepking and Bekkers 2012). Social contexts are social factors that have an impact on attitudes towards NPOs, such as the feeling of belonging to a community (Reed and Selbee 2001; Wilson 2012), prior engagement in and social ties to NPO activities (Sokolowski 1996) or, more generally, greater levels of social capital (Brown and Ferris 2007; Wang and Graddy 2008), as well as social incentives such as social conformity and social exchange (Bekkers 2010; Green and Webb 1997). Personality traits refer to the impact of the “Big Five” personality traits (Goldberg 1990). There is some evidence that greater levels of agreeableness, openness and extraversion have a generally positive impact on volunteerism and on donation willingness (Wilson 2012; Bekkers 2010, 2007). The group of attitudinal factors consist of general attitudinal dimensions that are not directly related to attitudes towards NPOs. For example, a rather strong and consistent finding is the positive effect of religiosity on attitudes towards NPOs (Becker and Dhingra 2001; Bekkers and Wiepking 2011; Helms and Thornton 2012). Another attitudinal factor that has an impact on attitudes towards NPOs are political attitudes: People who identify as conservative are prone to greater levels of charitable giving and volunteering than liberals (Margolis and Sances 2016; Brooks and Wilson 2007). A third relevant attitudinal dimension are values. There is some evidence that pro-social values have a positive impact on the formation of positive attitudes towards NPOs (Bekkers and Wiepking 2011; Wymer et al. 2006).

The goal of the present study is to contribute to the understanding of the impact of micro-level attitudinal factors. More specifically, we are measuring the impact of political cleavages, of religiosity as well as spirituality, and of values. In the following subsections, we briefly explain the rationale behind those attitudinal dimensions and the research questions we aim to address.

2. Research Questions

2.1. Impact of Political Cleavages

Existing research indicates that political attitudes have an impact on attitudes towards NPOs. Unfortunately, however, political attitudes can refer to any number of things: party preference, ideological self-identification, preferences on legislative matters, philosophical principles, and so forth. Depending on one’s specific understanding and operationalization of political attitudes, political attitudes can refer to very different concepts. One problem of this conceptual vagueness of political attitudes is that the resulting measurements can be very context-specific and not very insightful from a comparative perspective. For example, party affiliation in a dual-party system such as the United States is not comparable to party affiliation in a European-style multi-party system.

Instead of looking at political attitudes in a broad and vague manner, we are interested in the impact of a more narrow concept: Political cleavages (Lipset and Rokkan 1967). Political cleavages are policy dimensions that have strong saliency within a population. The cleavage structure within Western democracies has been changing for the past several decades. Traditional cleavages have gradually been superseded by the globalization-induced cleavages of cultural integration vs. demarcation and economic integration vs. demarcation (Dancygier and Walter 2015; Kriesi et al. 2006; Bornschier 2010). The attitudes towards the policy dimensions of culture and economy are at least somewhat generalizable, because those cleavages are present in different Western countries.

The research question related to political cleavages we aim to answer in this study is the following:

- What is the impact of political attitudes, understood in terms of the culture and economy cleavages, on attitudes towards NPOs?

2.2. Impact of Religiosity and Spirituality

Religiosity has been found, as mentioned above, to have a consistent positive effect on volunteering and donating activities. In our study, we include the dimension of religiosity as a predictor of attitudes towards NPOs. Religiosity, however, is not the only category of transcendental belief-system—significant portions of the populations in Western countries consider themselves “spiritual” to some degree (Heelas and Woodhead 2005). Spirituality is an inherently imprecise, fuzzy concept (Zinnbauer et al. 1997) that only partially correlates with religiosity. However, the fact that considerable proportions of Western populations consider themselves to be spiritual means that the concept of spirituality has, at the very least, some identity-building, performative power.

The fuzzy nature of spirituality makes it difficult to predict its impact on attitudes towards NPOs. Including both spirituality and religiosity in our analysis allows us to directly compare the effects of these two dimensions. If, for example, religiosity and spirituality showed similar effects, then the underlying causal mechanisms might be similar. If the effects are not similar, that could indicate that religiosity and spirituality represent distinct causal mechanisms.

The research question related to religiosity and spirituality we aim to answer is the following:

- What is the impact of religiosity and spirituality on attitudes towards NPOs?

2.3. Impact of Values

Values are a higher-order, generalized conceptualization of desirability of states in the world and of the morality of actions. Values are the foundation upon which specific preferences are generated (Hitlin and Piliavin 2004). Values act as a kind of “moral compass”: The specific attitudes we adopt towards some objects or propositions are based on our values. The value dimension we explore in this study is based on a Maslowian understanding of needs (Maslow 1943). From such a perspective, people form values on a survival vs. self-expression dimension, contingent on the degree of fulfillment of needs during their socialization. This mechanism of value formation is supported by observations of intergenerational value change (Inglehart 2008, 2015; Inglehart and Welzel 2010; Welzel and Inglehart 2010).

The relation of the survival vs. self-expression value dimension to attitudes towards NPOs has, so far, not been thoroughly explored and we do not yet know what effect, if any, there is. For example, it could be expected that a tendency towards survival has a negative impact on attitudes towards NPOs, since one is preoccupied with their own material needs and can spare no time or other resources on altruism. On the other hand, it could also be plausibly expected that a tendency for self-expression means a tendency for an egocentric, non-communitarian outlook on life, resulting in a negative effect on attitudes towards NPOs.

The research question related to values we aim to answer is the following:

- What is the impact of the survival vs. self-expression value dimension on attitudes towards NPOs?

3. Design, Data and Methods

To answer our research questions, we have conducted a representative survey among the Swiss population. Before delving into the data collection process, we first need to clarify how we have operationalized the response (dependent) and predictor (independent) variables.

3.1. Typology of NPOs

The survey participants of this study were not asked about their attitudes towards NPOs in general. Instead, they were asked about their attitudes towards six different types of NPOs. These six types are: Professional associations, charities, religious organizations, political organizations, cultural organizations, and sports organizations.

The typology we use is a simplified version of the typology proposed in the International Classification of Non-profit Organizations (ICNPO) (Salamon and Anheier 1997, 1996). We have opted for a simplified typology for two reasons. First, the full ICNPO typology is too complex to be meaningfully applied in a survey. Second, our simplification aims to employ a most different systems logic (Teune and Przeworski 1970): We have included NPO types that are so distinct from one another that no confusion should arise.

3.2. Operationalizing Attitudes towards NPOs

Our operationalization of attitudes towards NPOs consists of five dimensions in total. The survey items that correspond to these five dimensions are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Operationalization of attitudes towards NPOs.

The first dimension of attitudes towards NPOs is general interest. General interest in and of itself is not very informative, but it is a simple approximation of salience. With the next three items, we measure how likely the participants are to engage in specific actions pertinent to NPOs: Joining an NPO as a member, donating money to an NPO, and volunteering for an NPO. With the final item, we measure how interested the study participants are to work professionally for an NPO. Volunteering, donating, and becoming a member are traditional activities associated with the fnonprofit sector (Freeman 1997; García-Mainar and Marcuello 2007; Lee and Chang 2007; Tchirhart 2006). Professional paid work might not be as prevalent an activity as donating or volunteering, but it is a relevant part of the NPO ecosystem nonetheless (Leete 2006; Onyx and Maclean 1996), which is why we include it as an attitudinal dimension.

3.3. Operationalizing Political Cleavages, Religiosity and Spirituality, and Values

We have operationalized political cleavages of cultural integration vs. demarcation and of economic integration vs. demarcation with two items, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Operationalization of political cleavages.

The culture item is about immigration, and the economy item is about deregulation. We have phrased the deregulation question the way we did in order to minimize “contamination” with the cultural cleavage. For example, economic integration could also be measured by asking how the participants feel about the free movement of workers across borders for the sake of companies. Such an item, however, would possibly tap into the cultural cleavage dimension. The two items in Table 2 barely correlate (the correlation coefficient is 0.08), so they it is unlikely that they are measuring the same dimension.

The operationalization of religiosity and spirituality is done with two simple items, as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Operationalization of religiosity and spirituality.

The items for religiosity and spirituality correlate moderately (the correlation coefficient is 0.50). This is in line with the fuzzy nature of spirituality: Not all religious people are spiritual, and not all spiritual people are religious, but some people are both religious and spiritual.

The operationalization of the survival vs. self-expression value dimension consists of two items as well, as summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Operationalization of the survival vs. self-expression value dimension.

These two items have some degree of correlation (the correlation coefficient is 0.39), possibly indicating that they do not measure the opposite ends of one dimension. For that reason, we have not combined both items into a single scale but kept them separate in the data analysis. We suspect that the phrasing of both items was somewhat loaded and elicited an acquiescence effect.

3.4. Additional Variables

In addition to the variables described in the previous subsections, we have included a number of additional control variables in our analysis. They are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Control variables for the analysis.

Age, (biological) sex and educational level are socio-demographic variables that have been shown, in prior research, to have an impact on attitudes towards NPOs. We did not collect any ethnic data in the survey, but we included the information about the primary language of the participants (either German or French). The Swiss language divide is not an ethnic one, but an important cultural one. Finally, we have also included a measure of political self-assessment on a left to right scale. This political positioning item correlates only weakly with the economic cleavage item (0.14) and moderately with the immigration cleavage item (0.38).

3.5. Data Collection

To explore our research question, we have conducted an online survey among residents of the German- and French-speaking parts of Switzerland. The survey was fielded in February 2017 through a general population online panel curated by a market research firm1, and 735 participants have participated. Surveys that rely on online panels apply so-called nonprobability sampling (Callegaro et al. 2014), meaning that not every member of the target population has an equal probability of being included in the survey sample. A consequence of nonprobability sampling is that one cannot calculate survey variance (popularly referred to as “margin of error”). However, through a Bayesian approximation, it is possible to estimate so-called Bayesian credible intervals for online panel-based surveys (Roshwalb et al. 2016). The credible interval for the survey used in this study is 3.7%. Seventy-five percent of the survey respondents reside in the German-speaking part of Switzerland, and the other 25% in the French-speaking part; 49.9% of respondents are women; and the mean and median ages of all respondents are 43.8 and 45, respectively. The survey sample resembles the Swiss population closely, and we have decided against post hoc adjustments such as post-stratification or raking (Zhang 2000). Descriptive summaries of the data on attitudes towards NPOs as well as of the predictor variables is provided in the appendix.

3.6. Data Analysis and Researcher Degrees of Freedom

There are five outcome variables of interest, i.e., the five dimensions of attitudes towards NPOs. We have estimated the impact of the predictor variables on the five response variables, and we did so for each of the six NPO types separately. Overall, this results in 30 separate models.

We have estimated these models in the form of Bayesian regression models (Gelman et al. 2013). The specific form of our models is the following:

The above model is fairly simple: We use a normal distribution as the sampling distribution (noise distribution), and very broad, noncommittal priors both for the intercept and the coefficients . The prior for the standard deviation is also vague, a half-Cauchy distribution trunkated at zero (Polson and Scott 2012). Overall, this model puts great emphasis on the data and hardly any on the priors.

We have performed the model estimation with the package rstanarm (Gabry and Goodrich 2017) within the computational environment R (R Core Team 2015). The rstnarm package is based on the probabilistic programming language Stan (Carpenter et al. 2017). We have estimated all 30 models with 1000 warmup and 1000 sampling iterations for four separate sampling chains. The sampling chains for all models converged successfully, as indicated by the potential scale reduction factor (Gelman and Rubin 1992) of 1.0 for all estimates of all models.

In any data analysis context, so-called researcher degrees of freedom (Simmons et al. 2011) pose a challenge and a problem: Choices made prior to, during, and after the data analysis have a strong impact on the outcomes of the data analysis as well as the interpretation of the outcomes. In our data analytic approach, we have not engaged in any form of data dredging (Smith and Ebrahim 2002) at any point of the data analysis. Furthermore, we have avoided so-called p-hacking (Head et al. 2015) both in a direct (our Bayesian approach does not produce frequentist p-values) and an indirect way (we estimated the model as presented above in all 30 estimation instances, without any post hoc modifications to the data or the model). The main researcher degrees of freedom in our analysis pertain to the model specification. We posit a model that is as sparse as possible, and the priors we have chosen are very broad, non-specific priors that lie in the range of the plausible.

4. Results

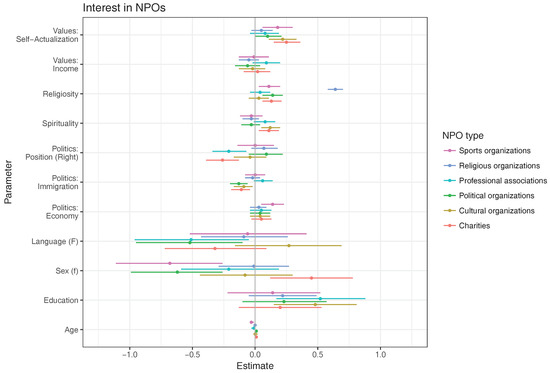

We present the results of the model estimations in graphical form. In each of the following subsections, the chart of interest contains the model estimates for one of the five dimensions of attitudes towards NPOs. The model estimates for the six different NPO types per response variable are all contained within a single chart; the different NPO types can be discerned by the different colors.

The charts contain two pieces of information. The first are the mean values for the parameter estimates, represented as dots. The second are the so-called 95% credible intervals, represented as lines. Credible intervals are what researches often believe confidence intervals to mean (Morey et al. 2016): The interval in which the true value of the parameter, given the data and the model, lies with some probability, in this case with 95% probability.

4.1. General Interest in NPOs

The estimation results for the six models with general interest in NPOs as the response variable are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Parameter estimates for the six models with interest in NPOs as the response (dependent) variable.

The first two variables, the self-actualization and the income variables, have unequal impact. Self-actualization has a robust, consistent effect for sports organizations, cultural organizations, and charities (in that the 95% credible interval line does not cross zero). The importance of income, on the other hand, has no consistent effect for any of the NPO types.

Religiosity and spirituality are similar in the direction of their impact: They have a positive effect for some NPO types, but not for the same ones. Most notably, religiosity has a very strong effect on the interest in religious organizations, whereas spirituality has no such effect.

The political variables have different kinds of impact. The further one positions themselves to the right, the lower the interest in professional associations and in charities. The stronger someone believes that there is too much immigration, the lower their interest in political and religious organizations as well as in charities. The stronger someone is in favor of deregulation, the more likely they are to be interested in sports organizations.

Among the socio-demographic variables, belonging to the French-speaking part of Switzerland and being female tend to have negative impact on some NPO types. The effect of sex is strongly negative for sports organizations and political organizations, but positive for charities. One additional educational level tends to increase interest in NPOs; the effect is consistent for professional associations and cultural organizations. Age has, overall, small and noisy effects; it is robust only for sports organizations: The younger someone is, the greater their interest in sports organizations.

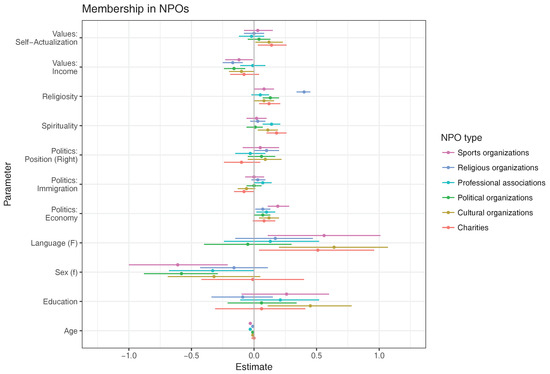

4.2. Becoming a Member

The estimation results for the six models with interest in joining an NPO as the response variable are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Parameter estimates for the six models with interest in becoming a member of an NPO as the response (dependent) variable.

The effects are not dissimilar to the results for general interest. In terms of values, self-actualization once again has some positive effects, albeit weaker ones and for fewer NPOs, only for cultural organizations and charities. The importance of income has a small negative effect for all NPO types except professional associations and charities. This could indicate that people who put greater importance on a stable income are hesitant to join NPOs because membership usually is not free.

The effects of religiosity and spirituality are both positive. However, the effect of religiosity on the interest in joining a religious organization is stronger than the effect of spirituality.

The self-positioning on the lef-right scale as well as the attitude towards immigration have no consistent effect on any NPO type. That is not true, however, for the deregulation variable: People who are in favor of deregulation tend to be more willing to join just about every NPO type except charities.

The socio-demographic variables have effects that are somewhat surprising given their effects on general interest. Most notably, being in the French-speaking part of Switzerland now has a positive effect for several NPO types, whereas it had no effect or negative effects on general interest. The effect of sex is similar as before: Being female has a strong negative impact on the willingness to join sports or political organizations. The previously observable positive effect of the level of education is present only for charities. Finally, age has a more pronounced negative effect: The younger someone is, the more likely they are to join a sports organization or a professional association.

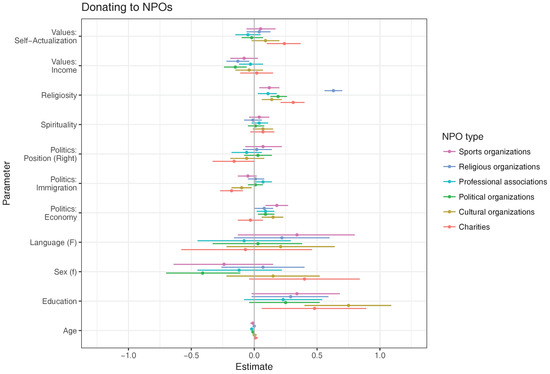

4.3. Donating

The estimation results for the six models with donation intention as the response variable are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Parameter estimates for the six models with donation intention as the response (dependent) variable.

The self-actualization and income variables have similar effects as before. The more someone values self-actualization, the more likely they are to donate—but only to charities. The more one values a stable income, on the other hand, the less likely they are to donate to religious and political organizations.

Religiosity and spirituality are different when it comes to donating. Whereas being more spiritual has no effect at all, being more religious makes one more likely to donate to all NPO types, especially to religious organizations.

The political self-positioning has a somewhat robust negative effect only for charities: The more one locates themselves to the right, the less likely they are to donate to charities. A slight negative effect for charities is also present for the immigration variable, along with a negative effect for cultural variables. For professional organizations, on the other hand, there is a slight positive effect. The deregulation variable, once again, has a small positive effect for most NPO types except for charities.

The socio-demographic variables have fewer consistent effects for donation intention than they did for the other response variables. Language has no consistent effect at all, and being female has a negative effect only for political organizations. Higher educational levels, however, have a positive effect both for charities and, rather strongly, for cultural organization. Age has no consistent effect for any of the NPO types.

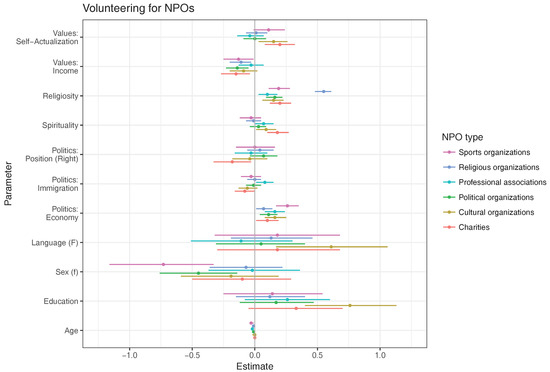

4.4. Volunteering

The estimation results for the six models with volunteering intention as the response variable are summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Parameter estimates for the six models with volunteering for an NPO as the response (dependent) variable.

The estimation results for the volunteering intentions are similar to the results for donation intentions. Self-actualization has a positive effect for cultural organizations and charities, whereas the income variable has a negative effect for all NPO types except professional and cultural organizations.

Religiosity and spirituality differ once again. Religiosity has a positive impact on the volunteering intention for all NPO types, especially religious organizations. Spirituality, in contrast, only has a positive impact on the volunteering intention for cultural organizations and charities.

The effects of the left-right self-assessment and of the immigration variable are similar to the donation intentions. Seeing oneself more to the right has a negative impact on the volunteering intention for charities. Similarly, believing that there is too much immigration has a positive impact on the volunteering intentions for professional associations and a negative impact for charities. The effects of the deregulation variable are, once again, positive, this time for all NPO types.

Among the socio-demographic variables, some common patterns of effects are observable. Being from the French-speaking part of Switzerland has a positive efect for cultural organizations, and being female has a negative effect for sports and for political organizations. A higher education level has, once again, a positive effect, but only for cultural organizations. Age has a slight, but robust negative effect for sports organizations and for professional associations.

4.5. Interest in Professional Work

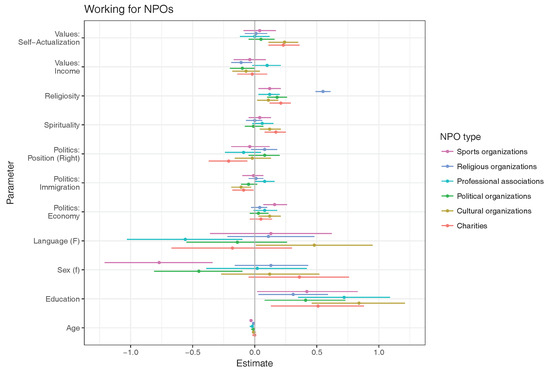

The estimation results for the six models with interest in working professionally for an NPO as the response variable are summarized in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Parameter estimates for the six models with interest in professional work for an NPO as the response (dependent) variable.

The self-actualization variable has, once again, a positive effect for cultural organizations and for charities. The income variable, on the other hand, once again has negative effects, namely for religious and political organizations.

The results for religiosity and spirituality are very similar to the previous ones. Religiosity has a consistently positive effect for all NPO types, especially for religious organizations. Spirituality, on the other hand, has a positive effect only for cultural organizations and for charities.

The general direction of effects for the left-right self-assessment and for the immigration attitude is similar to the previous effects. Seeing oneself as more to the right has a negative impact on the interest in working for charities, and being of the opinion that there is too much immigration has a negative impact for cultural organizations and for charities. Being in favor of deregulation has, once again, positive effects, but this time only for sports and for cultural organizations.

Among the socio-demographic variables, the most noticeable pattern of effects is present for educational level: The higher someone’s educational level, the more interested they are in working for any NPO, especially for cultural organizations and for professional associations. Being from the French-speaking part of Switzerland has a negative effect for religious organizations, but a positive effect for cultural organizations. The effects of sex follow a similar pattern as for the other response variables: Being female has a strong negative effect for sports organizations and a less strong, but still notable effect for political organizations. Age has, once again, a negative effect for sports organizations and for professional associations: The younger someone is, the more likely they are to be interested in working for one of those two NPO types.

5. Discussion

In the previous sections, we have presented the results of the model estimations. Even though the results of the 30 model estimations contain much information, the main insights from the results allow us to answer our research questions.

5.1. The Impact of Political Cleavages

We have operationalized political cleavages with two items, one for the cultural integration vs. demarcation cleavage and one for the economic integration vs. demarcation cleavage. The item for the cultural cleavage, the attitude towards immigration, tends to have a negative impact on attitudes towards some kinds of NPOs. For all five dimensions of attitudes towards NPOs, being of the opinion that there is too much integration has a negative impact for charities and, in most cases, for cultural organizations. Interestingly, the impact is not consistently negative: For professional associations, there is a positive impact. This could mean that the perception of too much immigration pertains to the economic cleavage after all: People might be prone to support and join professional associations precisely because they are worried about the effects of immigration.

The attitude towards deregulation, on the other hand, tends to have a positive impact only. This effect is most consistent and strongest for sports organizations, but it is also present for other NPO types, including professional associations. This pattern of effects might be explained by an underlying anti-regulation and pro civil society attitude of people who tend to be in favor of economic deregulation. People who favor keeping government as small as possible might feel obliged to engage with and contribute to civil society more.

5.2. The Impact of Religiosity and Spirituality

We have estimated effects of self-assessed religiosity and self-assessed spirituality. The pattern of effects is similar for all dimensions of attitudes towards NPOs and for all NPO types: Religiosity has a consistent positive effect (especially for religious organizations), whereas spirituality also exhibits positive effects, but less universally and less strongly so.

These results strongly suggest that the causal mechanisms of the impact of religiosity and spirituality on attitudes towards NPOs are not the same. The large contemporary religions are typically strongly communitarian in nature: The experiences of social belonging and of social obligations are very strong. Spirituality, on the other hand, can be very individualistic and fragmented and thus without a dominant pro-social impetus, both in doctrine and in practice.

5.3. The Impact of Values

We have measured the survival vs. self-expression value dimension with two items, a self-actualization item and an income item. The self-actualization item, the question of how important it is for someone to realize their ideas, ambitions, and dreams, has a pattern of positive effects. However, not for all NPO types: The effects are predominantly present for cultural organizations and for charities. The income item, the question of how important it is for someone to have a stable income, exhibits an opposite pattern: The income variable mostly produced negative effects. Notably, the only NPO type for which the income variable did not produce any negative effects are professional associations. This could indicate that people who value a stable income still see professional associations as beneficial, since they can make sure that their incomes stay stable.

Overall, the two value items resulted in effects that are consistent with one single value dimension of survival vs. self-expression. The more people value self-expression (as measured by self-actualization), the more positive (some of) the attitudes towards NPOs. The more people value survival (as measured by stable income), the more negative (some of) the attitudes towards NPOs.

6. Conclusions

The results of this study add to and expand existing research of micro-level attitudinal factors as potential determinants or antecedents of attitudes towards NPOs.

We have measured political cleavages with two items that correspond to the political cleavages of cultural integration vs. demarcation and economic integration vs. demarcation. The analysis of the impact of political cleavages should be pursued in future research since it could help link attitudes towards NPOs to attitudes on salient policy dimensions that transcend narrow structural contexts. The operationalization of cleavages should be expanded and validated in future research; the operationalization in the present study is only preliminary.

The results for the impact of religiosity are consistent with previous research: Higher levels of religiosity result in more positive attitudes towards NPOs. The inclusion of a spirituality item has shed additional light on this category of potential influence: Religiosity and spirituality are not the same on a conceptual level, and they are different in terms of their impact.

Finally, the items that we have implemented as an operationalization of the survival vs. self-expression value dimension have produced results that suggest that this value dimension plays a role in the formation of attitudes towards NPOs. However, as with our operationalization of political cleavages, future research should explore and validate different approaches towards measuring the survival vs. self-expression value dimension.

6.1. NPO Types Matter

One important insight from this study is the role of different NPO types. The effects of the predictors we analyzed are not uniform over all types of NPOs. Quite the opposite: Attitudes seem to be contingent on NPO type. Of course, the finding that attitudes are not the same towards all types of NPOs is not all that surprising, but rather plausible. In the public as well as the academic discourse on NPOs, however, there is a tendency to treat NPOs as one homogeneous “third sector” (Leete 2006). In the taxonomy of all social organizations, NPOs probably do belong to a family or cluster of organization types with shared traits. However, the fact that all NPOs share some traits does not mean that those traits are the only intrusive traits from the point of view of the general population. In other words: The fact that an NPO is an NPO matters, but additionally, it matters what kind of NPO it is. The taxonomic nature of NPOs is almost certainly more complex than the typology we propose in this study, but adding even such a single additional layer or level offers a more precise and less incomplete picture.

6.2. Implications for NPOs

The results of this study are of practical relevance for NPOs in at least two ways. First, NPOs can utilize the results in order to reduce the uncertainty in their strategic and marketing activities. More specifically, the results of this study can form the basis for deciding which population segments to target for what purpose. For example, targeting people with higher levels of religiosity is potentially an effective strategy. As another example, sports organizations might want to reduce their marketing efforts towards women because women have consistently less positive attitudes than men.

Second, NPOs can potentially develop strategies in order to appeal to certain types of people. For example, charities and cultural organizations are popular with people who value self-expression more. If, for example, professional associations wanted to attract people who value self-expression, then they might try to emulate the communication strategies and values of cultural organizations and charities.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Descriptives for the Attitudes towards NPOs

The descriptive information for general interest in different NPO types is summarized in Table A1.

Table A1.

Descriptives of general interest in NPOs.

Table A1.

Descriptives of general interest in NPOs.

| NPO Type | Mean | Median | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Professional associations | 4.54 | 5 | 2.67 |

| Charities | 5.9 | 6 | 2.59 |

| Religious organizations | 3.18 | 2 | 2.57 |

| Political organizations | 3.88 | 4 | 2.53 |

| Cultural organizations | 5.11 | 5 | 2.56 |

| Sports organizations | 5.19 | 5 | 2.86 |

The descriptive information for interest in joining an NPO type as a member is summarized in Table A2.

Table A2.

Descriptives of interest in joining as a member.

Table A2.

Descriptives of interest in joining as a member.

| NPO Type | Mean | Median | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Professional associations | 2.54 | 1 | 2.39 |

| Charities | 3.42 | 2 | 2.82 |

| Religious organizations | 2.16 | 1 | 2.18 |

| Political organizations | 2.30 | 1 | 2.10 |

| Cultural organizations | 3.28 | 2 | 2.60 |

| Sports organizations | 3.24 | 2 | 2.76 |

The descriptive information for donation willingness is summarized in Table A3.

Table A3.

Descriptives of donation willingness.

Table A3.

Descriptives of donation willingness.

| NPO Type | Mean | Median | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Professional associations | 2.42 | 1 | 2.28 |

| Charities | 5.02 | 5 | 3.25 |

| Religious organizations | 2.81 | 1 | 2.79 |

| Political organizations | 2.21 | 1 | 2.15 |

| Cultural organizations | 3.49 | 3 | 2.67 |

| Sports organizations | 3.40 | 2 | 2.74 |

The descriptive information for volunteering willingness is summarized in Table A4.

Table A4.

Descriptives of volunteering willingness.

Table A4.

Descriptives of volunteering willingness.

| NPO Type | Mean | Median | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Professional associations | 2.60 | 1 | 2.48 |

| Charities | 4.04 | 3 | 2.96 |

| Religious organizations | 2.52 | 1 | 2.47 |

| Political organizations | 2.36 | 1 | 2.21 |

| Cultural organizations | 3.59 | 3 | 2.78 |

| Sports organizations | 3.70 | 3 | 2.99 |

The descriptive information for interest in professional work for NPOs is summarized in Table A5.

Table A5.

Descriptives of interest in professional work.

Table A5.

Descriptives of interest in professional work.

| NPO Type | Mean | Median | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Professional associations | 3.60 | 3 | 2.82 |

| Charities | 4.88 | 5 | 3.04 |

| Religious organizations | 2.70 | 1 | 2.47 |

| Political organizations | 2.86 | 1 | 2.46 |

| Cultural organizations | 4.43 | 4 | 2.90 |

| Sports organizations | 4.36 | 4 | 3.04 |

Appendix B. Descriptives for the Predictor Variables

The descriptive information for the ordinal and metric predictor variables is summarized in Table A6.

Table A6.

Descriptives of metric and original predictor variables.

Table A6.

Descriptives of metric and original predictor variables.

| Variable | Mean | Median | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-actualization | 7.75 | 8 | 1.91 |

| Income | 8.24 | 9 | 1.96 |

| Politics: Economy | 5.1 | 5 | 2.32 |

| Politics: Immigration | 6.00 | 6 | 2.85 |

| Religiosity | 3.75 | 3 | 2.68 |

| Spirituality | 4.67 | 5 | 2.8 |

| Political position (left–right) | 4.05 | 4 | 1.48 |

| Age | 43.79 | 45 | 15.94 |

Absent from Table A6 are the variables sex (50.1% men), language region (75.0% German-speaking part, 25.0% French-speaking part), and educational level (6.1% primary level, 65.2% secondary level, 28.7% tertiary level).

References

- Balabanis, George, Ruth E. Stable, and Hugh C. Phillips. 1997. Market orientation in the top 200 British charity organizations and its impact on their performance. European Journal of Marketing 31: 583–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Penny Edgell, and Pawan H. Dhingra. 2001. Religious Involvement and Volunteering: Implications for Civil Society. Sociology of Religion 62: 315–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, René, and Pamala Wiepking. 2011. A Literature Review of Empirical Studies of Philanthropy: Eight Mechanisms That Drive Charitable Giving. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 40: 924–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, René, and Pamala Wiepking. 2011. Who gives? A literature review of predictors of charitable giving Part One: Religion, education, age and socialisation. Voluntary Sector Review 2: 337–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, René. 2007. Intergenerational Transmission of Volunteering. Acta Sociologica 50: 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, René. 2010. Who gives what and when? A scenario study of intentions to give time and money. Social Science Research 39: 369–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Ner, Avner, and Benedetto Gui. 2003. The Theory of Nonprofit Organizations Revisited. In The Study of the Nonprofit Enterprise. Boston: Nonprofit and Civil Society Studies, Springer, pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bornschier, Simon. 2010. The New Cultural Divide and the Two-Dimensional Political Space in Western Europe. West European Politics 33: 419–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, Arthur C., and James Q. Wilson. 2007. Who Really Cares: The Surprising Truth About Compassionate Conservatism, 1 reprint ed. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Eleanor, and James M. Ferris. 2007. Social Capital and Philanthropy: An Analysis of the Impact of Social Capital on Individual Giving and Volunteering. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 36: 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callegaro, Mario, Reg Baker, Jelke Bethlehem, Anja S. Göritz, Jon A. Krosnick, and Paul J. Lavrakas. 2014. Online panel research. In Online Panel Research. Edited by Mario Callegaro, Reg Baker, Jelke Bethlehem, Anja S. Göritz, Jon A. Krosnick and Paul J. Lavrakas. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Camarero, Carmen, and Ma Jose Garrido. 2012. Fostering Innovation in Cultural Contexts: Market Orientation, Service Orientation, and Innovations in Museums. Journal of Service Research 15: 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, Bob, Andrew Gelman, Matthew Hoffman, Daniel Lee, Ben Goodrich, Michael Betancourt, Marcus Brubaker, Jiqiang Guo, Peter Li, and Allen Riddell. 2017. Stan: A Probabilistic Programming Language. Journal of Statistical Software 76: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancygier, Rafaela M., and Stefanie Walter. 2015. Globalization, Labor Market Risks, and Class Cleavages. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2497406. Rochester: Social Science Research Network. [Google Scholar]

- Einolf, Christopher J. 2011. The Link Between Religion and Helping Others: The Role of Values, Ideas, and Language. Sociology of Religion 72: 435–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, Richard B. 1997. Working for Nothing: The Supply of Volunteer Labor. Journal of Labor Economics 15: S140–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabry, Jonah, and Ben Goodrich. 2017. rstanarm: Bayesian Applied Regression Modeling via Stan. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rstanarm/rstanarm.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2017).

- García-Mainar, Inmaculada, and Carmen Marcuello. 2007. Members, Volunteers, and Donors in Nonprofit Organizations in Spain. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 36: 100–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelman, Andrew, and Donald B. Rubin. 1992. Inference from Iterative Simulation Using Multiple Sequences. Statistical Science 7: 457–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelman, Andrew, John B. Carlin, Hal S. Stern, David B. Dunson, Aki Vehtari, and Donald B. Rubin. 2013. Bayesian Data Analysis, 3 rev. ed. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Gittell, Ross, and Edinaldo Tebaldi. 2006. Charitable Giving: Factors Influencing Giving in U.S. States. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 35: 721–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, Lews R. 1990. An alternative "description of personality": The big-five factor structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 59: 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, Corliss L., and Deborah J. Webb. 1997. Factors Influencing Monetary Donations to Charitable Organizations. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 5: 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gui, Benedetto. 1991. The Economic Rationale for the “third Sector”. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics 62: 551–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, Michael T., and John Freeman. 1977. The Population Ecology of Organizations. American Journal of Sociology 82: 929–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, Megan L., Luke Holman, Rob Lanfear, Andrew T. Kahn, and Michael D. Jennions. 2015. The Extent and Consequences of P-Hacking in Science. PLoS Biology 13: e1002106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heelas, Paul, and Linda Woodhead. 2005. The Spiritual Revolution: Why Religion is Giving Way to Spirituality. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Helmig, Bernd, Marc Jegers, and Irvine Lapsley. 2004. Challenges in Managing Nonprofit Organizations: A Research Overview. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 15: 101–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helms, Sara E., and Jeremy P. Thornton. 2012. The influence of religiosity on charitable behavior: A COPPS investigation. The Journal of Socio-Economics 41: 373–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitlin, Steven, and Jane Allyn Piliavin. 2004. Values: Reviving a Dormant Concept. Annual Review of Sociology 30: 359–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Christian Welzel. 2010. Changing Mass Priorities: The Link between Modernization and Democracy. Perspectives on Politics 8: 551–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, Ronald. 2008. Changing Values among Western Publics from 1970 to 2006. West European Politics 31: 130–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, Ronald. 2015. The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles Among Western Publics. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- John, Peter, Sarah Cotterill, Liz Richardson, Alice Moseley, Graham Smith, Gerry Stoker, and Corinne Wales. 2013. Nudge, Nudge, Think, Think: Experimenting with Ways to Change Civic Behaviour. London: A&C Black. [Google Scholar]

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier, and Timotheos Frey. 2006. Globalization and the transformation of the national political space: Six European countries compared. European Journal of Political Research 45: 921–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Yu-Kang, and Chun-Tuan Chang. 2007. Who gives what to charity? Characteristics affecting donation behavior. Social Behavior and Personality 35: 1173–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leete, Laura. 2006. Work in the nonprofit sector. In The Nonprofit Sector: A Research Handbook, 2nd ed. Edited by Waler W. Powell and Richard Steinberg. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 159–79. [Google Scholar]

- Lipset, Seymour Martin, and Stein Rokkan. 1967. Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. New York: Free Press, vol. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Mainardes, Emerson Wagner, Rozélia Laurett, Nívea Coelho Pereira Degasperi, and Sarah Venturim Lasso. 2017. External motivators for donation of money and/or goods. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 22: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, Michele F., and Michael W. Sances. 2016. Partisan Differences in Nonpartisan Activity: The Case of Charitable Giving. Political Behavior 39: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, Abraham H. 1943. A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review 50: 370–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morey, Richard D., Rink Hoekstra, Jeffrey N. Rouder, Michael D. Lee, and Eric-Jan Wagenmakers. 2016. The fallacy of placing confidence in confidence intervals. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 23: 103–23. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, Michael H., Pierre R. Berthon, Leyland F. Pitt, Marie E. Murgolo-Poore, and Wendy F. Ramshaw. 2001. An Entrepreneurial Perspective on the Marketing of Charities. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 9: 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Onyx, Jenny, and Madi Maclean. 1996. Careers in the third sector. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 6: 331–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polson, Nicholas G., and James G. Scott. 2012. On the Half-Cauchy Prior for a Global Scale Parameter. Bayesian Analysis 7: 887–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. 2015. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan, Sampath Kumar, and Walter H. Henley. 2008. Determinants of charitable donation intentions: A structural equation model. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 13: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, Paul B., and Kevin L. Selbee. 2001. The Civic Core in Canada: Disproportionality in Charitable Giving, Volunteering, and Civic Participation. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 30: 761–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshwalb, Alan, Neale El-Dash, and Clifford Young. 2016. Towards the Use of Bayesian Credibility Intervals in Online Survey Results. Technical report. Washington: Ipsos Public Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- Salamon, Lester M., and Helmut K. Anheier. 1996. The International Classification of Nonprofit Organizations: ICNPO-Revision 1. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Institute for Policy Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Salamon, Lester M., and Helmut K. Anheier. 1997. Defining the Nonprofit Sector: A Cross-National Analysis. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sargeant, Adrian. 1999. Charitable Giving: Towards a Model of Donor Behaviour. Journal of Marketing Management 15: 215–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegelmilch, Bodo B., Alix Love, and Adamantios Diamantopoulos. 1997. Responses to different charity appeals: The impact of donor characteristics on the amount of donations. European Journal of Marketing 31: 548–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, Joseph P., Leif D. Nelson, and Uri Simonsohn. 2011. False-Positive Psychology: Undisclosed Flexibility in Data Collection and Analysis Allows Presenting Anything as Significant. Psychological Science 22: 1359–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, George Davey, and Shah Ebrahim. 2002. Data dredging, bias, or confounding. British Medical Journal 325: 1437–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokolowski, S. Wojciech. 1996. Show me the way to the next worthy deed: Towards a microstructural theory of volunteering and giving. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 7: 259–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchirhart, Mary. 2006. Nonprofit Membership Associations. In The Nonprofit Sector: A Research Handbook, 2nd ed. Edited by Walter W. Powell and Richard Steinberg. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 523–41. [Google Scholar]

- Teune, Henry, and Adam Przeworski. 1970. The Logic of Comparative Social Inquiry. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Lili, and Elizabeth Graddy. 2008. Social Capital, Volunteering, and Charitable Giving. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 19: 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welzel, Christian, and Ronald Inglehart. 2010. Agency, Values, and Well-Being: A Human Development Model. Social Indicators Research 97: 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, Darin W., and Clovis F. Simas. 2008. An empirical investigation of the link between market orientation and church performance. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 13: 153–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiepking, Pamala, and René Bekkers. 2012. Who gives? A literature review of predictors of charitable giving. Part Two: Gender, family composition and income. Voluntary Sector Review 3: 217–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, John. 2012. Volunteerism Research: A Review Essay. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 41: 176–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wymer, Walter, Patricia Knowles, and Roger Gomes. 2006. Nonprofit Marketing: Marketing Management for Charitable and Nongovernmental Organizations. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Li-Chun. 2000. Post-Stratification and Calibration-A Synthesis. The American Statistician 54: 178–84. [Google Scholar]

- Zinnbauer, Brian J., Kenneth I. Pargament, Brenda Cole, Mark S. Rye, Eric M. Butter, Timothy G. Belavich, Kathleen M. Hipp, Allie B. Scott, and Jill L. Kadar. 1997. Religion and Spirituality: Unfuzzying the Fuzzy. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 36: 549–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1. | Innofact AG, http://innofact.ch/. |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).