Advancing a Distributive-Bargaining and Integrative-Negotiation Integral System: A Values-Based Negotiation Model (VBM)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

“A mature person is one who does not think only in absolutes, who is able to be objective even when deeply stirred emotionally, who has learned that there is both good and bad in all people and in all things, and who walks humbly and deals charitably with the circumstances of life, knowing that in this world no one is all knowing and therefore all of us need both love and charity.”—Eleanor Roosevelt

2. Buber: VBM’s Inspiration

2.1. Why Do Negotiators’ Feelings Matter to VBM?

2.2. Why Should Negotiators Care about Interpersonal Relationships?

2.3. Why Theorize an Integral Values-Based Negotiation System?

2.4. Why Create a Negotiations Model Fused with Religious Tenets?

3. Rationale and Assumptions: The Connection between Interpersonal Communication and the Psychology of Religion (as One of Many Possible Sources of Personal Values)

4. Rationale and Assumptions: The Connection between Interpersonal Communication and Cognition

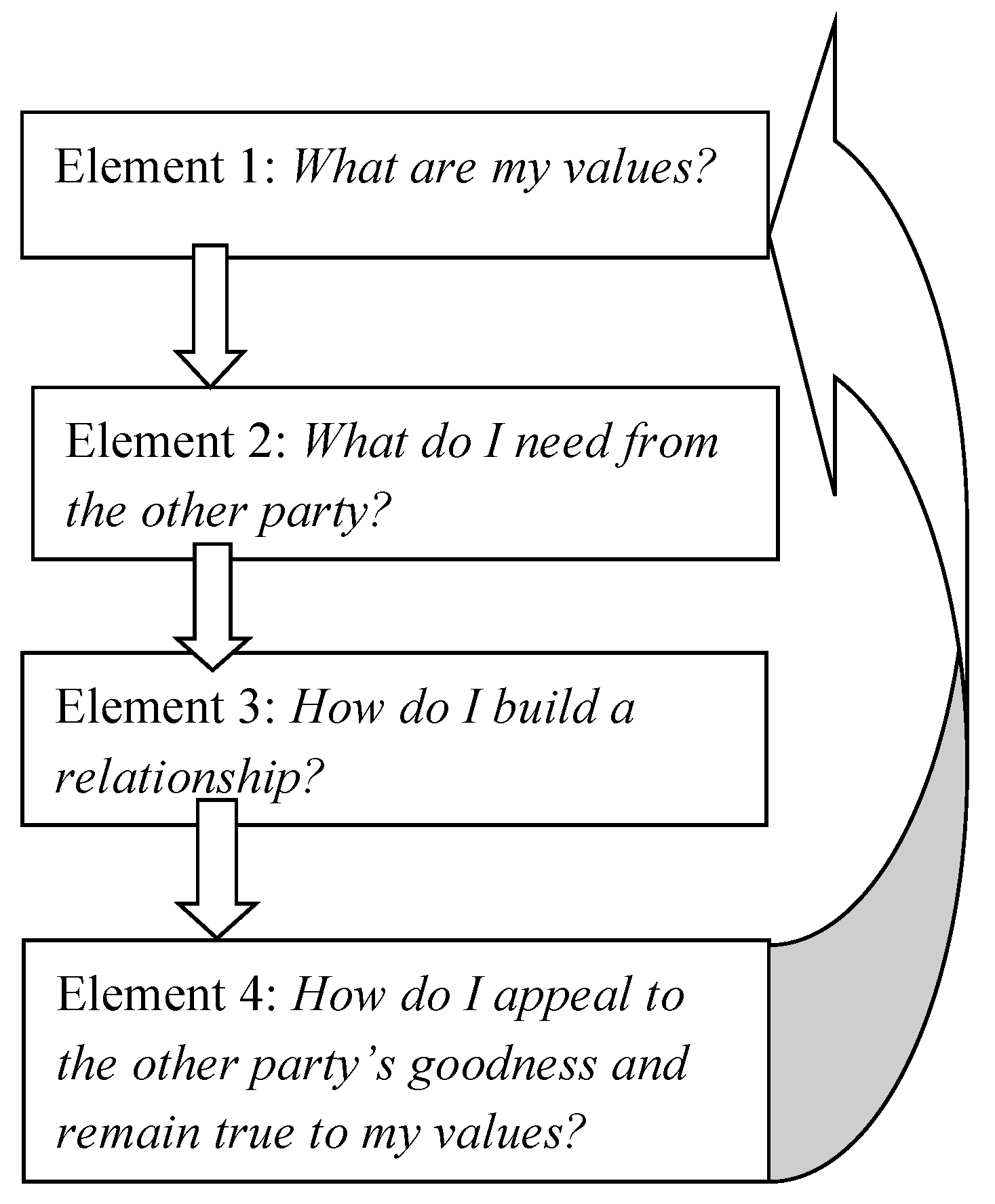

5. The Model

- (1)

- What are my values?

- (2)

- What do I need from the other party?

- (3)

- How do I build a relationship?

- (4)

- How do I appeal to the other party’s goodness and remain true to my values?

- (1)

- Cycle through my values, need/s, desired relationship, and appeal; and

- (2)

- Can I arrive at a negotiated agreement within the mutually agreed deadline or timeframe?

5.1. First Element (Pre-Negotiation): What Are My Values?

5.2. Second Element (the Goals): What Do I Need from the Other Party?

5.3. Third Element (the Plan/s): How Do I Build a Relationship?

5.4. Fourth Element (the Action): How Do I Appeal to the Other Party’s Goodness and Remain True to My Values?

6. Limitations of and Future Directions for VBM

7. Practical Considerations, Implications, and Applications of VBM

8. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adler, Robert S., Benson Rosen, and Elliot M. Silverstein. 1998. Emotions in Negotiation: How to Manage Fear and Anger. Negotiation Journal 14: 161–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Ali M., and Osvaldo Salas. 2011. Implicit Influences of Christian Religious Representations on Dictator and Prisoner’s Dilemma Game Decisions. The Journal of Socio-Economics 40: 242–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almakias, Shaul, and Avi Weiss. 2012. Ultimatum Game Behavior in Light of Attachment Theory. Journal of Economic Psychology 33: 515–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariely, Dan. 2008. Predictably Irrational. New York: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Ashwell, Douglas. 2003. The Bargain Exercise. Business Communication Quarterly 66: 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, Konika, and Paul Bloom. 2013. Would Tarzan Believe in God? Conditions for the Emergence of Religious Belief. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 17: 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, Bruce, and Ingrid Smithey Fulmer. 2004. Methodological Challenges in the Study of Negotiator Affect. International Negotiation 9: 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, Bernard. M., and Ruth Bass. 2008. The Bass Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, and Managerial Applications, 4th ed. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bear, Julia B., and Dikla Segel-Karpas. 2015. Effects of Attachment Anxiety and Avoidance on Negotiation Propensity and Performance. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research 8: 153–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechara, Antoine. 2004. The Role of Emotion in Decision-Making: Evidence from Neurological Patients with Orbitofrontal Damage. Brain and Cognition 55: 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, Robert. D. 1998. Negotiation and Evil: The Sources of Religious and Moral Resistance to the Settlement of Conflicts. Mediation Quarterly 15: 245–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonab, Bagher Ghobari, and Ali Akbar Haddadi Koohsar. 2011. Reliance on God as a Core Construct of Islamic Psychology. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Science 30: 216–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretfeld, Sven. 2012. Resonant Paradigms in the Study of Religions and the Emergence of Theravāda Buddhism. Religion 42: 273–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brion-Meisels, Linda, and Steven Brion-Meisels. 2012. Peace Education across Cultures: Applications of the Peaceable Schools Framework in the West Bank. Peace & Change 37: 572–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buber, Martin. 1952. Eclipse of God: Studies in the Relation between Religion and Philosophy. Atlantic Highlands: Humanities Press International. [Google Scholar]

- Buber, Martin. 1958. I and Thou, 2nd ed. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, Robert A. Baruch, and Joseph P. Folger. 2005. The Promise of Mediation: The Transformative Approach to Conflict. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, C. Daryl, B. Keith Payne, and John M. Doris. 2013. Morality in High Definition: Emotion Differentiation Calibrates the Influence of Incidental Disgust on Moral Judgments. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 49: 719–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, John R., and Carsten K. W. De Dreu. 2014. Egocentrism Drives Misunderstanding in Conflict and Negotiation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 51: 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugh, Dolly, Mary C. Kern, Zhu Zhu, and Sujin Lee. 2014. Withstanding Moral Disengagement: Attachment Security as an Ethical Intervention. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 51: 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchland, Patricia Smith. 2008. The Impact of Neuroscience on Philosophy. Neuron 60: 409–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clobert, Magali, and Vassilis Saroglou. 2013. Intercultural Non-Conscious Influences: Prosocial Effects of Buddhist Priming on Westerners of Christian Tradition. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 37: 459–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffelt, Tina A., and Jon A. Hess. 2015. Sexual Goals-Plans-Actions: Toward a Sexual Script in Marriage. Communication Quarterly 63: 221–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colzato, Lorenza S., Ilja van Beest, Wery P. M. van den Wildenberg, Claudia Scorolli, Shirley Dorchin, Nachshon Meiran, Anna M. Borghi, and Bernhard Hommel. 2010. God: Do I Have Your Attention? Cognition 117: 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crilly, Donal, Na Ni, and Yuwei Jiang. 2016. Do-No-Harm versus Do-Good Social Responsibility: Attributional Thinking and the Liability of Foreignness. Strategic Management Journal 37: 1316–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curhan, Jared R., Hillary Anger Elfenbein, and Heng Xu. 2006. What Do People Value When They Negotiate? Mapping the Domain of Subjective Value in Negotiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 91: 493–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damasio, Antonio, and Gil B. Carvalho. 2013. The Nature of Feelings: Evolutionary and Neurobiological Origins. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 14: 143–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Der Foo, Maw, Hillary Anger Elfenbein, Hwee Hoon Tan, and Voon Chuan Aik. 2004. Emotional Intelligence and Negotiation: The Tension between Creating and Claiming Value. International Journal of Conflict Management 15: 411–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, James Price, and David C. Schrader. 1998. Reply: On the Utility of the Goals-Plans-Action Sequence. Communication Studies 49: 300–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennis, Leslie Sturdivant. 2008. The Inevitability of Conflict and the Importance of its Resolution in Christian Higher Education. Christian Higher Education 7: 339–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, Miguel, Anna-Kaisa Newheiser, Guy Kahane, and Zoe de Toledo. 2013. Scientific Faith: Belief in Science Increases in the Face of Stress and Existential Anxiety. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 49: 1210–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, Roger, and William Ury. 1981. Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement without Giving in. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Flannelly, Kevin. J., and Kathleen Galek. 2010. Religion, Evolution, and Mental Health: Attachment Theory and ETAS Theory. Journal of Religion and Health 49: 337–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, Ivan. 2014. Teaching Goals-Plans-Action Theory through a Negotiation Exercise. Communication Teacher 28: 246–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervais, Will M., and Ara Norenzayan. 2012. Like a Camera in the Sky? Thinking about God Increases Public Self-Awareness and Socially Desirable Responding. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 48: 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, Geoffrey P., and John M. Darley. 2008. The Psychology of Meta-Ethics: Exploring Objectivism. Cognition 106: 1339–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, Geoffrey P., and John M. Darley. 2012. Why are Some Moral Beliefs Perceived to be More Objective Than Others? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 48: 250–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, Marco, Antonio Maurizio Branca, and Gianfranco Morena. 2011. An Experimental Study of the Reputation Mechanism in a Business Game. Simulation & Gaming 42: 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harinck, Fieke, and Gerben A. Van Kleef. 2012. Be Hard on the Interests and Soft on the Values: Conflict Issue Moderates the Effects of Anger in Negotiations. British Journal of Social Psychology 51: 741–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henningsen, Mary Lynn Miller, Kathleen S. Valde, Gregory A. Russell, and Gregory R. Russell. 2011. Student–Faculty Interactions about Disappointing Grades: Application of the Goals–Plans–Actions Model and the Theory of Planned Behavior. Communication Education 60: 174–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henningsen, Mary Lynn Miller, Kathleen S. Valde, and Jessica Denbow. 2013. Academic Misconduct: A Goals–Plans–Action Approach to Peer Confrontation and Whistle-Blowing. Communication Education 62: 148–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, Marsha A. 2008. Attachment Theory, Religious Beliefs, and the Limits of Reason. Pastoral Psychology 57: 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, Joshua A., and Laura A. King. 2008. Religious Commitment and Positive Mood as Information about Meaning in Life. Journal of Research in Personality 42: 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillebrandt, Annika, and Laurie J. Barclay. 2017. Comparing Integral and Incidental Emotions: Testing Insights from Emotions as Social Information Theory and Attribution Theory. Journal of Applied Psychology 102: 732–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, Camille S., and Joris Lammers. 2012. The Powerful Disregard Social Comparison Information. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 48: 329–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, Jonathan, Jamin Halberstadt, and Matthias Bluemke. 2012. Foxhole Atheism, Revisited: The Effects of Mortality Salience on Explicit and Implicit Religious Belief. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 48: 983–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaveney, Susan M. 2008. The Blame Game: An Attribution Theory Approach to Marketer–Engineer Conflict in High-Technology Companies. Industrial Marketing Management 37: 653–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilmann, Ralph H., and Kenneth W. Thomas. 1977. Developing a Forced-Choice Measure of Conflict-Handling Behavior: The “Mode” Instrument. Educational and Psychological Measurement 37: 309–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, Lee A. 2012. Attachment Theory and the Evolutionary Psychology of Religion. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 22: 231–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuttner, Ran. 2012. Cultivating Dialogue: From Fragmentation to Relationality in Conflict Interaction. Negotiation Journal 28: 315–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurin, Kristin, Aaron C. Kay, and David Moscovitch. 2008. On the Belief in God: Towards an Understanding of the Emotional Substrates of Compensatory Control. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 44: 1559–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Daniel B. 2009. Communicating Minds: Subjectivity, Objectivity, and Understanding. Studies in Communication Sciences 9: 17–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Sujin, and Leigh Thompson. 2011. Do Agents Negotiate for the Best (or Worst) Interest of Principals? Secure, Anxious and Avoidant Principal–Agent Attachment. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 47: 681–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon-Perez, Jose M., Francisco J. Medina, and Lourdes Munduate. 2010. Effects of Self-Efficacy on Objective and Subjective Outcomes in Transactions and Disputes. International Journal of Conflict Management 22: 170–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicki, Roy J., David M. Saunders, and Bruce Barry. 2015. Negotiation, 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Luyten, Patrick, and Jozef Corveleyn. 2008. Attachment and Religion: The Need to Leave Our Secure Base: A Comment on the Discussion between Granqvist, Rizzuto, and Wulff. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 17: 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallery, Paul, Suzanne Mallery, and Richard Gorsuch. 2000. A Preliminary Taxonomy of Attributions to God. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 10: 135–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinko, Mark J., Scott C. Douglas, and Paul Harvey. 2006. Attribution Theory in Industrial and Organizational Psychology: A Review. International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology 21: 127–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, Cornelia, Elisa Ciaramelli, Flavia De Luca, and Eleanor A. Maguire. 2017. Comparing and Contrasting the Cognitive Effects of Hippocampal and Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex Damage: A Review of Human Lesion Studies. Neuroscience. in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miner, Maureen H. 2008. Healthy Questing and Mature Religious Reflection: Critique, Antecedents, and Relevance of Attachment Theory? Journal of Psychology of Theology 36: 222–33. [Google Scholar]

- Northouse, Peter Guy. 2015. Introduction to Leadership, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, Jo K., and Crystal I. C. Farh. 2017. An Emotional Process Theory of How Subordinates Appraise, Experience, and Respond to Abusive Supervision Over Time. Academy of Management Review 42: 207–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olekalns, Mara, and Philip Leigh Smith. 2013. Dyadic Power Profiles: Power-Contingent Strategies for Value Creation in Negotiation. Human Communication Research 39: 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ome, Blessing N. 2013. Personality and Gender Differences in Preference for Conflict Resolution Styles. Gender and Behavior 11: 5512–24. [Google Scholar]

- Promta, Somparn. 2010. The View of Buddhism on Other Religions. The Muslim World 100: 302–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proudfoot, Wayne, and Phillip Shaver. 1975. Attribution Theory and the Psychology of Religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 14: 317–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purzycki, Benjamin Grant. 2013. The Minds of Gods: A Comparative Study of Supernatural Agency. Cognition 129: 163–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reb, Jochen. 2010. The Influence of Past Negotiations on Negotiation Counterpart Preferences. Group Decision and Negotiation 19: 457–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinert, Duane F., Carla E. Edwards, and Rebecca R. Hendrix. 2009. Attachment Theory and Religiosity: A Summary of Empirical Research with Implications for Counseling Christian Clients. Counseling and Values 53: 112–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Jennifer, Marta Sinclair, Jutta Tobias, and Ellen Choi. 2017. More Dynamic Than You Think: Hidden Aspects of Decision-Making. Administrative Sciences 7: 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, Jeffrey. Z., and Walter C. Swap. 1994. Small Group Theory: Forming Consensus through Group Processes. In International Multilateral Negotiation. Edited by I. William Zareman. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, pp. 132–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sabee, Christina M., Carma L. Bylund, Jennifer Gueguen Weber, and Ellen Sonet. 2012. The Association of Patients’ Primary Interaction Goals with Attributions for Their Doctors’ Responses in Conversations about Online Health Research. Journal of Applied Communication Research 40: 271–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagioglou, Christina, and Matthias Forstmann. 2013. Activating Christian Religious Concepts Increases Intolerance of Ambiguity and Judgment Certainty. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 49: 933–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samp, Jennifer A., and Denise Haunani Solomon. 2005. Toward a Theoretical Account of Goal Characteristics in Micro-Level Message Features. Communication Monographs 72: 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakun, Melvin F. 2006. Spiritual Rationality: Integrating Faith-Based and Secular-Based Problem Solving and Negotiation as Systems Design for Right Action. Group Decision and Negotiation 15: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariff, Azim F., and Ara Norenzayan. 2007. God is Watching You: Priming God Concepts Increases Prosocial Behavior in an Anonymous Economic Game. Psychological Science 18: 803–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spilka, Bernard, and Greg Schmidt. 1983. General Attribution Theory for the Psychology of Religion: The Influence of Event-Character on Attributions to God. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 22: 326–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilka, Bernard, Phillip Shaver, and Lee A. Kirkpatrick. 1985. A General Attribution Theory for the Psychology of Religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 24: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, John, Karen E. Zediker, and Laura Black. 2004. Relationships among Philosophies of Dialogue. In Dialogue: Theorizing Difference in Communication Studies. Edited by Rob Anderson, Leslie A. Baxter and Kenneth N. Cissna. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Stroope, Samuel, Scott Draper, and Andrew L. Whitehead. 2013. Images of a Loving God and Sense of Meaning in Life. Social Indicators Research 111: 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taves, Ann. 2008. Ascription, Attribution, and Cognition in the Study of Experiences Deemed Religious. Religion 38: 126–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzafrir, Shay S., Rudolph Joseph Sanchez, and Keren Tirosh-Unger. 2012. Social Motives and Trust: Implications for Joint Gains in Negotiations. Group Decision and Negotiation 21: 839–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kleef, Gerben A., Carsten K. W. De Dreu, Davide Pietroni, and Antony S. R. Manstead. 2006. Power and Emotion in Negotiation: Power Moderates the Interpersonal Effects of Anger and Happiness on Concession Making. European Journal of Social Psychology 36: 557–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, Bernard. 1985. An Attributional Theory of Achievement Motivation and Emotion. Psychological Review 92: 548–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willard, Aiyana K., and Ara Norenzayan. 2013. Cognitive Biases Explain Religious Belief, Paranormal Belief, and Belief in Life’s Purpose. Cognition 129: 379–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Tian, and Jing Zhou. 2012. Feelings and Comparisons in Negotiation: One Subjective Outcome, Two Different Mechanisms. Public Personnel Management 41: 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Liane, and A. J. Durwin. 2013. Moral Realism as Moral Motivation: The Impact of Meta-Ethics on Everyday Decision-Making. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 49: 302–06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gan, I. Advancing a Distributive-Bargaining and Integrative-Negotiation Integral System: A Values-Based Negotiation Model (VBM). Soc. Sci. 2017, 6, 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6040115

Gan I. Advancing a Distributive-Bargaining and Integrative-Negotiation Integral System: A Values-Based Negotiation Model (VBM). Social Sciences. 2017; 6(4):115. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6040115

Chicago/Turabian StyleGan, Ivan. 2017. "Advancing a Distributive-Bargaining and Integrative-Negotiation Integral System: A Values-Based Negotiation Model (VBM)" Social Sciences 6, no. 4: 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6040115

APA StyleGan, I. (2017). Advancing a Distributive-Bargaining and Integrative-Negotiation Integral System: A Values-Based Negotiation Model (VBM). Social Sciences, 6(4), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6040115