Time Heals All (Shallow) Wounds: A Lesson on Forgiveness of Ingroup Transgressors Learned by the Feyenoord Vandal Fans

Abstract

1. Forgiveness of Ingroup Transgressors

2. Study 1

2.1. Method

Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Results and Discussion

3. Study 2

3.1. Method

Participants

3.2. Materials

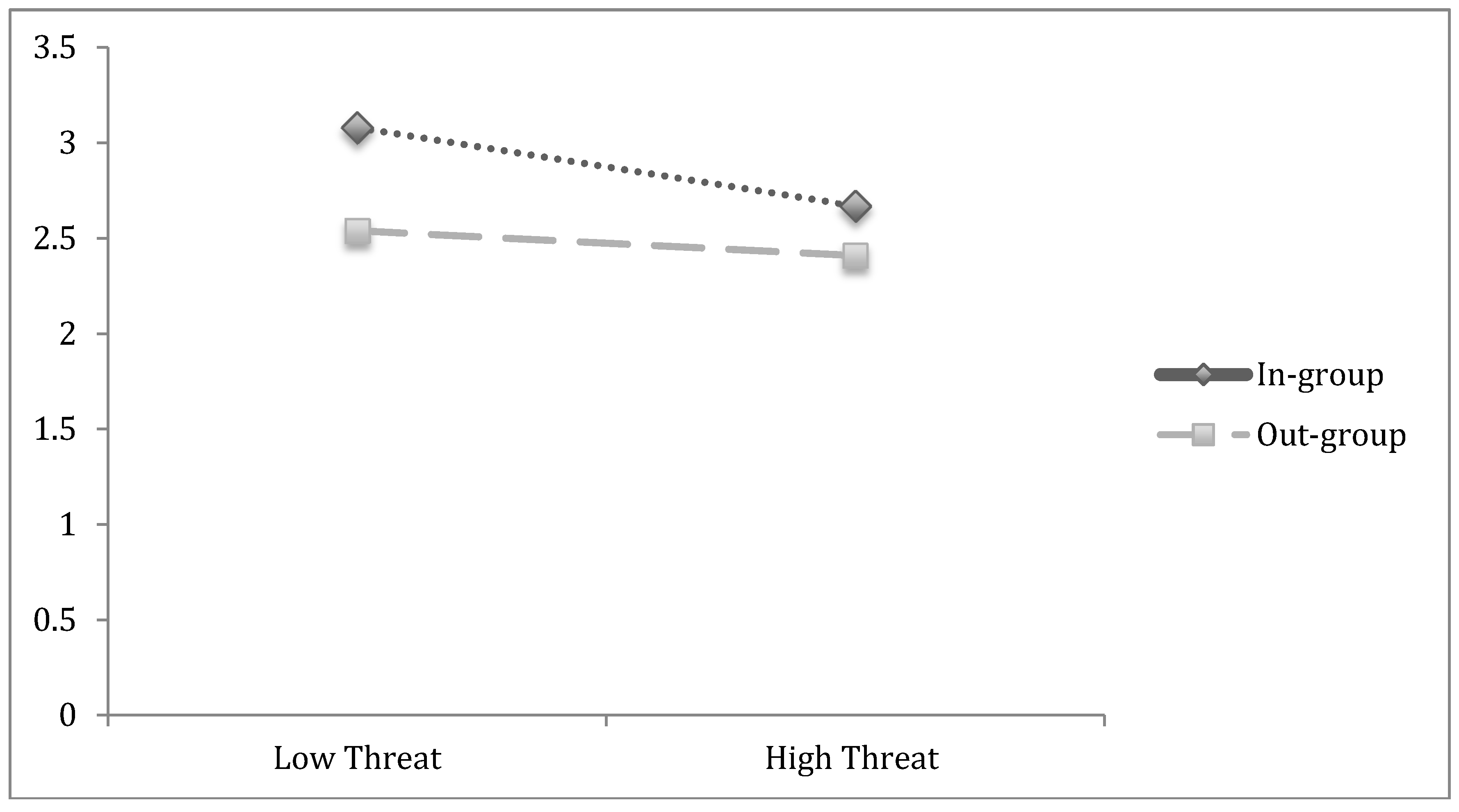

4. Results and Discussion

5. General Discussion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abrams, Dominic, and Michael A. Hogg. 1988. Comments on the motivational status of self-esteem in social identity and intergroup discrimination. European Journal of Social Psychology 18: 317–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, Dominic, and Michael A. Hogg, eds. 1990. Social Identity Theory: Constructive and Critical Advances. New York: Springer-Verlag Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Abrams, Dominic, José M. Marques, Nicola Bown, and Michelle Henson. 2000. Pro-norm and anti-norm deviance within and between groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 78: 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begue, Laurent. 2001. Social judgment of abortion: A black-sheep effect in a Catholic sheepfold. The Journal of Social Psychology 141: 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettencourt, B. Ann, Mark Manning, Lisa Molix, Rebecca Schlegel, Scott Eidelman, and Monica Biernat. 2015. Explaining Extremity in Evaluation of Group Members Meta-Analytic Tests of Three Theories. Personality and Social Psychology Review 20: 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biernat, M., Theresa K. Vescio, and Laura S. Billings. 1999. Black sheep and expectancy violation: Integrating two models of social judgment. European Journal of Social Psychology 29: 523–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branscombe, Nyla R., Daniel L. Wann, Jeffrey G. Noel, and Jason Coleman. 1993. Ingroup or outgroup extemity: Importance of the threatened social identity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 19: 381–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, Marilynn B. 1991. The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 17: 475–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, Marilynn B. 2007. The social psychology of intergroup relations: Social categorization, ingroup bias, and outgroup prejudice. In Social psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles. Edited by Arie W. Kruglanski and E. Tory Higgins. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 695–715. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Ryan P., Michael J. A. Wohl, and Julie Juola Exline. 2008. Taking up offenses: Secondhand forgiveness and group identification. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 34: 1406–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castano, Emanuele, Maria-Paola Paladino, Alastair Coull, and Vincent Y. Yzerbyt. 2002. Protecting the ingroup stereotype: Ingroup identification and the management of deviant ingroup members. British Journal of Social Psychology 41: 365–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, Renita, Natalie Stroud, Gina Chen, Maxwell McCombs, and Dominic Lasorsa. 2016. Us vs. Them: Online Incivility, Black Sheep Effect, and More. Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Enright, Robert D., Suzanne Freedman, and Julio Rique. 1998. The psychology of interpersonal forgiveness. In Exploring Forgiveness. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 46–62. [Google Scholar]

- Giannoli, V. 2015. Roma Devastata dai Tifosi Olandesi [Rome Devastated by Dutch Supporters]. Retrieved 10 November. Available online: http://roma.repubblica.it/cronaca/2015/02/20/news/europa_league_-107752865/ (accessed on 20 February 2015).

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2012. PROCESS: A Versatile Computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modelling. Available online: http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2017).

- Hornsey, Matthew J., and Jolanda Jetten. 2003. Not being what you claim to be: Impostors as sources of group threat. European Journal of Social Psychology 33: 639–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Yueh-Ting, and Victor Ottati. 1995. Perceived ingroup homogeneity as a function of group membership salience and stereotype threat. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 21: 610–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, John M., and José M. Marques. 2016. Norm violators as threats and opportunities: The many faces of deviance in groups. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations 19: 545–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, Jose M., Dominic Abrams, Dario Paez, and Michael A. Hogg. 2001a. Social Categorization, Social Identification, and Rejection of Deviant Group Members. In Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology. Group Processes. Edited by Michael A. Hogg and R. Scott Tindale. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, José, Dominic Abrams, and Rui G. Serôdio. 2001b. Being better by being right: subjective group dynamics and derogation of ingroup deviants when generic norms are undermined. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 81: 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, José M., and Dario Paez. 1994. The ‘black sheep effect’: Social categorization, rejection of ingroup deviates, and perception of group variability. European Review of Social Psychology 5: 37–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, José M., and Vincent Y. Yzerbyt. 1988. The black sheep effect: Judgmental extremity towards ingroup members in inter and intra-group situations. European Journal of Social Psychology 18: 287–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, José M., Vincent Y. Yzerbyt, and Jacques-Philippe Leyens. 1988. The “black sheep effect”: Extremity of judgments towards ingroup members as a function of group identification. European Journal of Social Psychology 18: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, Michael E., Frank D. Fincham, and Jo-Ann Tsang. 2003. Forgiveness, forbearance, and time: The temporal unfolding of transgression-related interpersonal motivations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 84: 540–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, M. E., Jr., Everett L. Worthington, and Chris Rachal. 1997. Interpersonal forgiving in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 73: 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLernon, Frances, Ed Cairns, Miles Hewstone, and Ron Smith. 2004. The development of intergroup forgiveness in Northern Ireland. Journal of Social Issues 60: 587–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, Saaid A., Sean P. Lane, and David M. Amodio. 2014. For members only ingroup punishment of fairness norm violations in the ultimatum game. Social Psychological and Personality Science 5: 662–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, Michael E., Kenneth I. Pargament, and Carl E. Thoresen, eds. 2001. Forgiveness: Theory, Research, and Practice. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miron, Anca M., Nyla R. Branscombe, and Monica Biernat. 2010. Motivated shifting of justice standards. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 36: 768–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutz, Diana C., and Byron Reeves. 2005. The new videomalaise: Effects of televised incivility on political trust. American Political Science Review 99: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, Masi, Nyla R. Branscombe, and Miles Hewstone. 2015. When group members forgive: Antecedents and consequences. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations 18: 577–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otten, Sabine. 2009. Social categorization, intergroup emotions, and aggressive interactions. In Intergroup Relations: The Role of Motivation and Emotion. London: Psychology Press, pp. 162–81. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Michael E. McCullough, and Carl E. Thoresen. 2000. The frontier of forgiveness. In Forgiveness: Theory, Research and Practice. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 299–319. [Google Scholar]

- Pickett, Cynthia L., and Marilynn B. Brewer. 2001. Assimilation and differentiation needs as motivational determinants of perceived in-group and out-group homogeneity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 37: 341–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, Isabel R., José M. Marques, John M. Levine, and Dominic Abrams. 2010. Membership status and subjective group dynamics: Who triggers the black sheep effect? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 99: 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, Isabel R., José M. Marques, and Dario Paez. 2015. National identification as a function of perceived social control: A subjective group dynamics analysis. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations 19: 236–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, Isabel R., José M. Marques, John M. Levine, and Dominic Abrams. 2016. Membership role and subjective group dynamics: Impact on evaluative intragroup differentiation and commitment to prescriptive norms. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations 19: 570–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronk, Tila M., Johan C. Karremans, Geertjan Overbeek, Ad A. Vermulst, and Daniël H. J. Wigboldus. 2010. What it takes to forgive: When and why executive functioning facilitates forgiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 98: 119–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rullo, Marika, Fabio Presaghi, and Stefano Livi. 2015. Reactions to ingroup and outgroup deviants: An experimental group paradigm for black sheep effect. PLoS ONE 10: e0125605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rullo, Marika, Fabio Presaghi, and Stefano Livi. 2016. We Will Forgive but Not Forget: The Ups and Downs of Intergroup Second-hand Forgiveness. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Rullo, Marika, Stefano Livi, Giuseppe Pantaleo, and Rosita Viola. 2017. When the Black Sheep Is Not So «Black»: Social Comparison as a Standard for Ingroup Evaluation in Classrooms. Journal of Educational, Cultural and Psychological Studies (ECPS Journal) 1: 107–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinada, Mizuho, Toshio Yamagishi, and Yu Ohmura. 2004. False friends are worse than bitter enemies: “Altruistic” punishment of in-group members. Evolution and Human Behavior 25: 379–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, Henri, and John C. Turner. 1979. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Monterey: Brooks/Cole Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- Travaglino, Giovanni A., Dominic Abrams, Georgina Randsley de Moura, José M. Marques, and Isabel R. Pinto. 2014. How groups react to disloyalty in the context of intergroup competition: Evaluations of group deserters and defectors. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 54: 178–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, Esther, Marieke van den Bosch, Emanuele Castano, and Petra Hopman. 2010. Dealing with deviants: The effectiveness of rejection, denial, and apologies on protecting the public image of a group. European Journal of Social Psychology 40: 282–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Lei, Jiehui Zheng, Liang Meng, Qiang Lu, and Qingguo Ma. 2016. Ingroup favoritism or the black sheep effect: Perceived intentions modulate subjective responses to aggressive interactions. Neuroscience Research 108: 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wohl, Michael JA, and Nyla R. Branscombe. 2005. Forgiveness and collective guilt assignment to historical perpetrator groups depend on level of social category inclusiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 88: 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, Everett L., Jr., Taro A. Kurusu, Wanda Collins, and Jack W. Berry. 2000. Forgiving usually takes time: A lesson learned by studying interventions to promote forgiveness. Journal of Psychology and Theology 28: 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yzerbyt, V., M. Dumont, D. Wigboldus, and E. Gordijn. 2003. I feel for us: The impact of categorization and identification on emotions and action tendencies. British Journal of Social Psychology 42: 533–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | As we did not have enough time to sample participants following the standard routine, Dutch, and Non-Dutch-non-Italian participants were contacted on personal basis (email and social networks such as Twitter and Facebook) in order to be sure of their nationality. Participants filled the survey on voluntary basis. The link to the survey was made available on a web page known by only those people who accepted to participate. The survey was written in English, it means that only those participants with the requested language skills were involved in the survey. |

| 2 | Eleven participants failed in filling all questions of the survey, thus they were excluded from the analysis. |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rullo, M.; Presaghi, F.; Livi, S.; Mazzuca, S.; Dessi, R. Time Heals All (Shallow) Wounds: A Lesson on Forgiveness of Ingroup Transgressors Learned by the Feyenoord Vandal Fans. Soc. Sci. 2017, 6, 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6030083

Rullo M, Presaghi F, Livi S, Mazzuca S, Dessi R. Time Heals All (Shallow) Wounds: A Lesson on Forgiveness of Ingroup Transgressors Learned by the Feyenoord Vandal Fans. Social Sciences. 2017; 6(3):83. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6030083

Chicago/Turabian StyleRullo, Marika, Fabio Presaghi, Stefano Livi, Silvia Mazzuca, and Roberto Dessi. 2017. "Time Heals All (Shallow) Wounds: A Lesson on Forgiveness of Ingroup Transgressors Learned by the Feyenoord Vandal Fans" Social Sciences 6, no. 3: 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6030083

APA StyleRullo, M., Presaghi, F., Livi, S., Mazzuca, S., & Dessi, R. (2017). Time Heals All (Shallow) Wounds: A Lesson on Forgiveness of Ingroup Transgressors Learned by the Feyenoord Vandal Fans. Social Sciences, 6(3), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6030083