What Are the Main Challenges Impeding Implementation of the Spatial Plans in Egypt Using Ecotourism Development as an Example?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Planning system in Egypt

- The Supreme Council for Planning and Urban Development (SCPUD), headed by the Prime Minister, according to Law No. 119/2008, with membership consisting of ministers and authorities competent in issues regarding spatial development, and includes ten non-government experts specialising in relevant issues (Government 2008).

- The General Organization of Physical Planning (GOPP) is mandated to develop the national policy for preparing the strategic spatial plans at the different levels. GOPP has seven Regional Planning Centres (RPCs) for spatial development. Each centre acts as a decentralised arm of GOPP by preparing, implementing and monitoring strategic plans within the regions. The RPCs cooperate with the Governorates and their local authorities, providing them with the required technical support and assisting in preparing, reviewing and implementing detailed plans (Government 2008). Additionally, in each Governorate, there is an Urban Planning Directorate (UPD) in charge of the implementation of plans and programmes prepared by the GOPP and its RPCs, including taking enforcement action. Each UPD is also responsible for preparing local detailed plans for the area which falls into its Governorate’s boundaries, based on the adopted strategic plans (Government 2008; GOPP 2013).

- The first group is tourism agencies and includes the Supreme Council of Tourism (SCT), and the Ministry of Tourism (MOT) and its units—Egyptian Tourist Authority (ETA) and Tourism Development Authority (TDA). TDA, which is seen as the key actor in this group, is mandated as being responsible for development planning of tourism regions and supervising the execution of development plans.

- The second group is the environmental agencies and encompasses the Ministry of State for Environmental Affairs (MSEA) and its executive arm, the Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA). EEAA is seen as the key actor in this group and is mandated as being responsible for protecting and promoting the environment. Its primary role is the implementation of national environmental plans by coordinating activities with competent administrative authorities.

3. Research Methodology

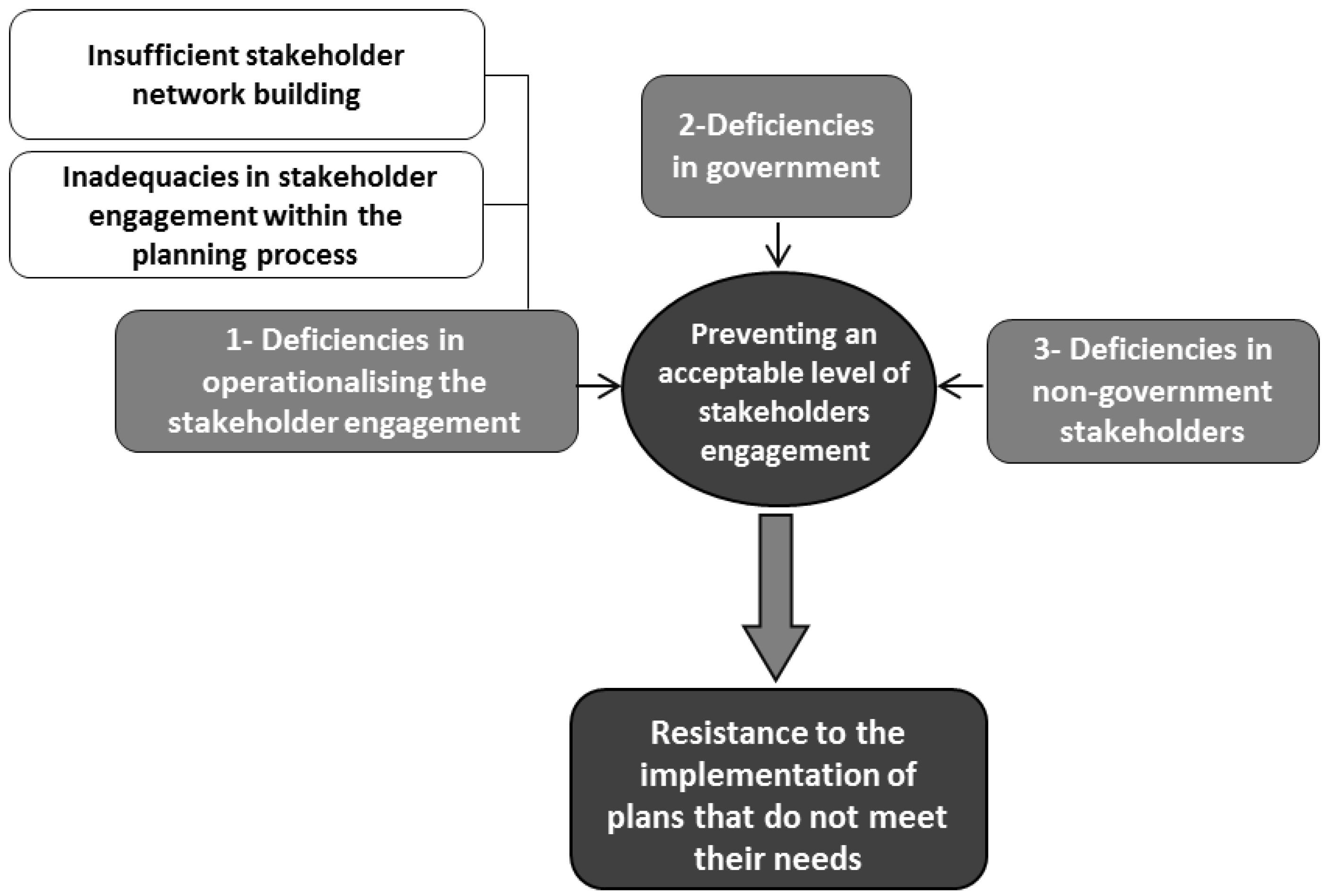

4. Developing a Conceptual Framework

4.1. The Potentials of Collaborative Planning Approach to Address the Challenges in the Traditional Approaches

4.2. Challenges to the Stakeholders Involvement and Collaboration in the Developing Countries

- Insufficient stakeholder network is as a result of:

- Deficiencies in identifying the relevant stakeholders at the outset may lead to marginalisation of key stakeholders who may be important for the planning and implementation process;

- The lack or poor analysis of stakeholders is one of the main reasons for a limited understanding of the diversity of their power and the relationships between them. This can lead to inappropriate roles being defined and levels of participation for each stakeholder group being misunderstood (Schmeer 2001;)

- Inadequacies in stakeholder engagement within the planning process is as a result of:

- Late stakeholder engagement during the planning process is often cited as a critical reason why stakeholders are resistant to the plan and its implementation because they believe that the decisions have already been made (Tseng and Penning-Rowsell 2012;)

- Inappropriate and insufficient methods of stakeholder involvement in each stage of the planning process.

- A lack of coordination and highly fragmented government agencies lead to significant overlap and duplication in their plans and activities for the same resources;

- A lack of resources including information, financial resources, and human capacity leads to an inability to put the development plans into practice (Wafik 2002); and

- The lack of an appropriate legal framework leads to dualism in functions and conflicting roles between the authorities charged with ecotourism development (Choi 2005).

- A lack of trust in the government as a result of previous unmet promises;

- A lack of awareness about participation requirements and process during ecotourism planning; and

- Widespread illiteracy and a low standard of living within the communities means that individuals are more concentrated on meeting daily needs and providing the basic public services, rather than looking forward to an aspiring future (Dogra and Gupta 2012).

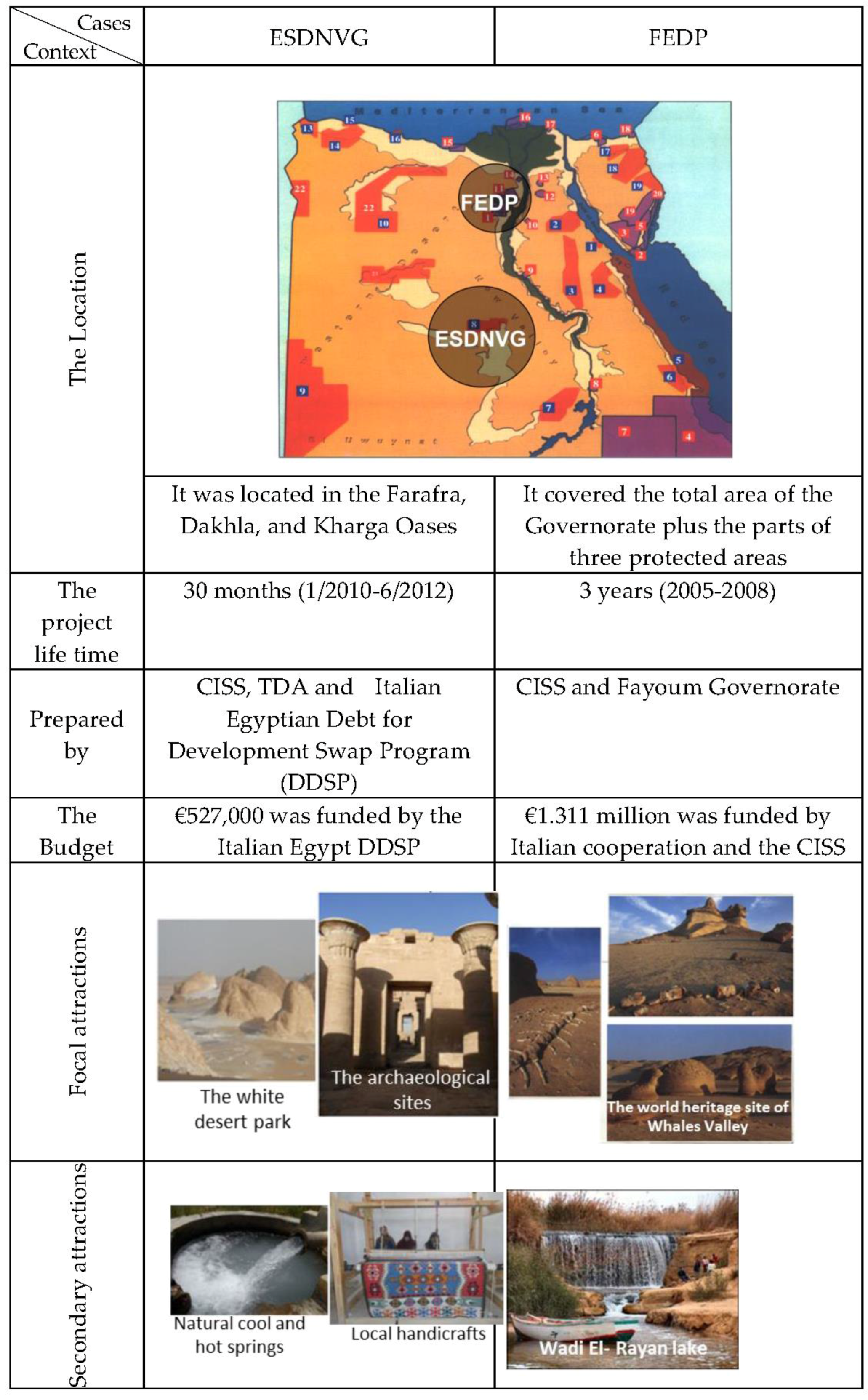

5. The Egyptian Ecotourism Initiatives

- Fayoum Ecotourism Development Plan 2005–2015 (FEDP) covered the total area of the Fayoum Governorate plus the parts of Qarun Lake, Wadi El-Rayan and Wadi E-Hitan protected areas. The total budget of the FEDP was €1.311 million, which was funded by the Italian government and an Italian NGO, CISS, which focuses on sustainable development more generally and ecotourism in particular. Each contributed half of the initiative budget as a grant to the Egyptian government (CISS 2013). The FEDP lasted three years (2005 to 2008). The FEDP outcome was designed to provide the Fayoum Governorate with an overall assessment of the existing condition of resources related to ecotourism development and to put forward an action plan to increase the capacity for ecotourism in the Fayoum Governorate (CISS and EDG 2008).

- Ecotourism for Sustainable Development in the New Valley Governorate (ESDNVG) was initiated to improve the livelihood of communities through ecotourism development and a more effective management of environmental and cultural resources. The main outcome was proposed future ecotourism development projects based on the results of the inventory and analytical phases.

6. Evaluation and Analysis of Egyptian Ecotourism Planning Initiatives

6.1. Deficiencies in Operationalising the Stakeholder Engagement; Two Key Deficiencies in the Way the Planning Process Works Have Been Identified

6.1.1. Insufficient Stakeholder Network Building was as a Result of

6.1.2. Inadequacies in Stakeholder Engagement within the Planning Process

- Normally, the diagnosis phase comprised two main methods. The first was individual or group interviews and surveys. This was inappropriate for large-scale developments with geographically dispersed stakeholders, such as with the FEDP and the ESDNVG. Therefore “the planning team needed to look at complementary techniques such as drop-in centres” (EC-8). A second approach was the public meetings designed to introduce the initiatives to interested stakeholders. These took place, but were largely tokenistic because the meetings were dominated by the governmental representatives, and limited information was disseminated to the stakeholders and many enquiries remained unanswered (EC-20).

- The analysis phase also encompassed two main techniques. ESDNVG provided a good example of using workshops to involve the stakeholders during the analysis phase. One of the interviewees described that: “the convener divided stakeholders into small groups (10–14 people) to prepare the SWOT analysis of ecotourism development in the NVG” (PS-21). In addition, “they used the role-playing techniques to encourage communication between the stakeholders and test their knowledge about the ecotourism development planning” (EC-20). Secondly, a questionnaire has been used by ESDNVG. However, in practice this was not an appropriate technique to gain meaningful input during the analysis phase because the respondents’ answers were very brief and careless (EC-1).

- The workshops in the development phase of both initiatives involved a one-way direction of information (from the convener to the stakeholders). Also, one public meeting (a legal requirement) was insufficient to gain support for a large-scale development with geographically dispersed stakeholders. Feedback was very limited because the majority of participants did not know anything about the initiative beforehand (EC-24).

- Stakeholder involvement events after the plan had been completed were concerned with awareness-raising programmes and campaigns for running ecotourism activities. It was generally felt that they would have been better if they had been concerned with building the stakeholder commitment to the plan implementation (PS-12).

- Agendas were often lacking, and there was no way of enabling stakeholders to shape the agenda to reflect their concerns;

- Often information was not presented in a clearly understandable manner to the audiences;

- The timing of the meetings was inappropriate for many stakeholders as they took place during normal working days, meaning many could not get time off to attend (NG-1);

- The structure of the meetings was organised in such a way that stakeholders did not have enough time to provide their inputs (EC-3); and

- There was a lack of follow-up, meaning that the stakeholders were not kept informed of meeting outcomes (EC-29).

6.2. Deficiencies in the Government

- -

- A lack of coordination: Although ecotourism development requires intensive coordination between concerned authorities, there was and remains considerable overlap and conflict of responsibilities, a lack of communication between authorities, and plans that are incompatible.

- A lack of communication between and amongst the authorities where each one of them cannot ask about the plans of others so that they can be reviewed or considered in any future plans (PS-14).

- The coordinating bodies such as National Centre for Planning State Lands Usage do not have any legal mandate to harmonise conflicts between different agencies (EC-7);

- A lack of transparency in decision-making between government authorities; and

- Each chairperson of these agencies is fighting for his/her personal achievements without thinking clearly about the public interest (EC-13).

- -

- Lack of information: Information is seen as one of the most important resources both for the development process and a means to build consensus between the stakeholders. However, information about ecotourism development in Egypt is limited because the majority of the developments are located in peripheral areas and there are no detailed databases for many resources (EC-8). In the same way, one of the interviewees claimed that “There are several authorities concerned with collecting and analysing data, such as Information and Decision Support Centre and various information centres in each governorate. However, there is no integrated and updated database” (EC-3). Consequently, “Ecotourism initiatives consume more than 20% of their time and budgets to build their own information databases. It would be better if there was an integrated national information system” (EC-12). Further to this, the information was not disseminated comprehensively to allow stakeholders to participate effectively (EC-24).

- -

- Lack of financial resources: Financial resources are probably the most significant ingredient for ecotourism development planning and effective stakeholder participation. Due to the limited financial capabilities of the state, there is a lack of financial resources to initiate and support the development planning process in general and ecotourism in particular (EC-5). This is because the stakeholder participation required high cost over a long time to cover preparing, motivating and then participating activities (EC-11).

- -

- Lack of Capacity of the governmental staff was a significant challenge during the planning process. Although the TDA was the focal actor in ecotourism development, the majority of staff did not have any basic knowledge about ecotourism development because of a rapid turnover of staff leading to a lack of experience. Therefore, the TDA often hired experienced consultants to prepare these kinds of projects (EC-20). However “The staff in the specialist ecotourism department in TDA gained a good experience during the initiatives. As soon as the project ended they left to work in the private sector for better positions and salaries” (PS-4). As a result of this, in any ecotourism development initiatives, there has been a follow-up by the staff lacking relevant experience and knowledge of both ecotourism development specifically and the planning process in general. This adversely affects the final outcomes (EC-28). Similarly, there is a lack of capacity in the staff of the EEAA, which is considered to be the main partner of the TDA in ecotourism development. In this regard, one of the interviewees claimed that “The staff of EEAA believe that protected areas would be destroyed by any ecotourism development within them. They do not have any idea about international cases for appropriate development within the protected areas” (EC-1). Further to this, they do not have any skills concerning how to compromise with, and accommodate, other authorities’ needs with respect to the regulations. Hence, one interviewee claimed that “The main reason for the majority of conflicts between EEAA and TDA is the staff of EEAA insisting on their opinions being right. Several cases could have been resolved through negotiation but they refused. EEAA regulations could not be challenged or compromised” (EC-5).

- -

- Lack of an appropriate legal framework: An appropriate legal framework is necessary to support ecotourism development and define the stakeholder roles during the process. Although there are a huge number of laws and decrees concerned with the tourism facilities and services individually, there is no overarching legislation concerned with sustainable tourism development plans or defining the roles of the stakeholders during the planning and implementation phases (PS-3). In this regard, another interviewee commented that “The tourism facilities have been governed by various legislations such as environmental law (4/1994 and 9/2009), protected areas law (102/1983), local development law (43/1979) and the decree of TDA establishment (374/1991)” (PS-8). Therefore, coherence and consistency between these different legislations are urgent priorities for enhancing the ecotourism development (EC-7). In the same way, another interviewee claimed that “Until now, Egypt has not had legislation that includes a national definition of ecotourism, its types and activities, which areas are appropriate for ecotourism development and what ecotourism development features are acceptable” (PS-10). There is also an urgent need for a legal framework to identify clear responsibilities for the authorities that are charged with tourism development and how any conflicts will be resolved (EC-10). Indeed, Hegazy (2010) has noted that a lack of clarity of responsibilities among the relevant authorities and agencies leads to weak regulatory compliance and enforcement. One interviewee confirmed this view by asserting that “Unfortunately, each one of the relevant authorities assumes that it has [the] upper hand in the tourism areas. It needs to implement the laws from its understanding. Therefore, the legislation should clarify how actors will collaborate during the planning and implementation process to mitigate the conflicts” (EC-15).

6.3. Deficiencies in the Non-Governmental Stakeholders; These Include:

- Negative experiences and previous unmet promises. In this respect, one of the interviewees commented that “How can we trust in the government and participate with them after several failed attempts and many promises often going unmet?” (LC-1). The stakeholders, particularly the local communities, have negativity towards any governmental activities because they believe that the government only involves them to endorse its own decisions and complete donor requirements (NG-1). Hence, “The response of the local communities during the planning process of FEDP was negative because they had previously engaged similar initiatives before them without any real attempt to address their issues” (PS-18).

- A lack of transparency in government information and decision-making process. In this respect, a member of one of the local communities commented that “There is no transparency in the information provided by or decisions made by the government. They did not speak with us once about project budgets and how they are spent. What reasons explain the inability of plan implementation? At least they should involve us in trying to address any deficiencies” (LC-2). Another interviewee claimed that “The government did not respect our views. They always decided what they needed because they believed that we were not aware of all the circumstances of the project” (NG-3).

- Changing the decisions based on political adjustments rather than long-term visions. In this regard, one interviewee remarked that “There are no strategic decisions adopted by the government. Any change in the highest-ranking staff is always followed by total change in decisions. Therefore, we are not confident in any promises of the government” (EC-8).

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albert, Karin, Thomas Gunton, and J.C. Day. 2003. Achieving Effective Implementation: An Evaluation of a Collaborative Land Use Planning Process. Available online: http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Achieving (accessed on 12 August 2013).

- Aref, Fariborz, and Marof B. Redzuan. 2008. Barriers to Community Participation toward Touirsm Development in Shiraz, Iran. Pakistan Journal of Social Sciences 5: 936–40. [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein, Sherry R. 1969. A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planning 35: 216–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayoumy, Rania. 2007. Urban Planning Methods for New Settlements in Egypt. Master Dissertation, Faculty of Urban and Regional, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla, Juan Carlos. 2008. Participatory Planning for Sustainable Cruise Ship Tourism in Mesoamerican Reef Destinations. Paper presented at the Second International Conference on Responsible Tourism in Destinations, Kerala, India, March 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, Jeffrey J., John Neary, and Blessing E. Asuquo. 2007. A Critical Needs Assessment for Collaborative Ecotourism Development Linked to Protected Areas in Cross River State, Nigeria. United States Forest Service International Collaboration with the Cross River State Tourism Bureau, cross River State Forestry Commission, and Cross River National Park; Washington: The United States Forest Service Department of Agriculture International Programs Office.

- Chemonics. 2006. Destination Management Framework- Enhancing the Competitiveness of the South Red Sea of Egypt. Egypt LIFE Red Sea Project. Washington: Chemonics International Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Bokeun. 2005. Barriers to Effective Collaboration between Stakeholders in Sustainable Tourism. Ph.D. Thesis, School of Management Studies for the Service Sector, University of Surrey, Surrey, UK. [Google Scholar]

- CISS. 2013. Ecotourism for a sustainable development: A Sustainable tourism program for the Governorate of Fayoum Italian Cooperation in Egypt: Development Cooperation Projects 2013. Available online: http://www.utlcairo-cooperazione.org/english/progetti/progetti/ciss_en.html (accessed on 1 April 2013).

- CISS, and EDG. 2008. Fayoum Ecotourism Development Plan 2005–2015. Fayoum: Cooperation International South-South & EDG. [Google Scholar]

- CISS, and EDG. 2012. Ecotourism for Sustainable Development in the New Valley Governorate. Fayoum: CISS & Environmental Design Group. [Google Scholar]

- De Araujo, Lindemberg Medeiros. 2000. Stakeholder Participation in Regional Tourism Planning: Brazil’s Costa Dourada Project. Ph.D. Dissertation, Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield, UK; p. 375. [Google Scholar]

- Dogra, Ravinder, and Anil Gupta. 2012. Barriers to Community Participation in Tourism Development: Empirical Evidence from a Rural Destination. SAJTH 5: 131–42. [Google Scholar]

- Dukeshire, Steven, and Jennifer Thurlow. 2002. Challenges and Barriers to Community Participation in Policy Development. Nova Scotia: Rural Communities Impacting Policy Project. [Google Scholar]

- El-Barmelgy, Hesham. 2002. An Appraisal for Sustainable Tourism and Development in Developing Countries (Case Study: Resort Based Development of the Northwest Coast of Egypt). Ph.D. Dissertation, Urban and Regional Planning, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt. [Google Scholar]

- Godwin, Dawn V. 1999. Collaboration as a Tool for Creating Sustainable Natural Resource Based Economies in Rural Areas. Master’s Dissertation, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Government, Egyptian. 2008 Law No. 119 of 2008: The unified building law, GOPP, Egypt.

- GOPP. 2013. GOPP responsibilities. Available online: http://www.gopp.gov.eg/MasterPages/About_Resp.aspx (accessed on 18 March 2013).

- Gray, Barbara. 1989. Collaborating Finding Common Ground for Multiparty Problems, 1st ed.San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Ghada Farouk. 2010. Participatory Planning Experiences in Egyptian Cities: Pragmatic Approach towards Sustainability. Paper presented at the 2nd International Conference on Sustainable Architecture & Urban Development—SAUD, Amman, Jordon, July 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, Patsy. 2006. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies, 2nd ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hegazy, Ibrahim. 2010. Strategic Environmental Assessment and Urban Planning System in Egypt. Ph.D. Thesis, Civic Design, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, Moham. 2011. Protected Areas in Egypt, 2nd ed. Cairo: EEAA. [Google Scholar]

- Imran, Sophia, Khorshed Alam, and Narelle Beaumont. 2011. A holistic conceptual framework for sustainable tourism management in protected areas. Paper presented at the Cambridge Business & Economics Conference, Cambridge, UK, June 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, Richard. 2007. Collaboration as a Strategy for Developing Cross-Cutting Policy Themes: Sustainable Development in the Wales Spatial Plan. Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Civic Design, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Kamarudin, Khairul Hisyam. 2013. Local stakeholders’ participation in developing sustainable community based rural tourism (CBRT): The case of three villages in the East Coast of Malaysia. Paper presented at the International Conference on Tourism Development, University Sains Malaysia Penang, G. Hotel, Penang, Malaysia, February 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kansas. 2013. The Community Tool Box. Available online: http://ctb.ku.edu/en/tablecontents/index.aspx (accessed on 29 July 2013).

- Kenawy, Emad. 2015. Collaborative Approach for Developing a More Effective Regional Planning Framework in Egypt: Ecotourism Development as Case Study. Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Geography and Planning, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Kenawy, Emad, and David Shaw. 2014. Developing a more effective regional planning framework in Egypt: the case of ecotourism. In Sustainable Tourism VI. Edited by Carlos A. Brebbia, Srecko Favro and Francisco Diaz Pineda. Southampton: WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment, pp. 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Joon Sik. 2002. A Collabrative Partnership Approach to Integrated Waterside Revitalisation: the Experience of the Mersey Basin Campaign, North West of England. Ph.D. Dissertation, Civic Design Department, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Loughlin, John, and Mohamed Nada. 2012. Do We Need to Rethink Egypt’s Territorial Governance and Planning for Economic Development? [Google Scholar] The Strategic National Development Support Project, UN-Habitat, Ministry of Housing & Utilities and Urban Development and Ministry of Local Development, Cairo, Egypt.

- Margerum, Richard. 2011. Beyond Consensus: Producing Results from Collaborative Environmental Planning and Management. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mazmanian, Daniel A., and Paul A. Sabatier. 1989. Implementation and Public Policy. Lanham: University Press of America. [Google Scholar]

- MPIC. 2012. Strategic Framework for Economic and Social Development plan until year 2022. In Proposal for Community Dialogue; Cairo: Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation. [Google Scholar]

- Monjardin, Laura. 2004. A Collaborative Approach to Water Allocation in a Coastal Zone of Mexico. Ph.D. Dissertation, Civic Design Department, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Preskill, Hallie, and Nathalie Jones. 2009. A Practical Guide for Engaging Stakeholders in Developing Evaluation Questions. Evaluation Series; Princeton: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Schmeer, Kammi. 2001. Stakeholder Analysis Guidelines. In Section 2 of Policy Toolkit for Strengthening Health Reform. Washington: Partners for Health Reform. [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby, Mohie Edeen. 2012. Realities of the Sustainable Planning Process of Egyptian Industrial Zones: The case of the Industrial Parks. Ph.D. Dissertation, School of City and Regional Planning, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, Cevat. 2000. Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tourism Management 21: 613–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Chin-Pei, and Edmund Penning-Rowsell. 2012. Micro-political and related barriers to stakeholder engagement in flood risk management. The Geographical Journal 178: 253–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wafik, Tarek. 2002. The Discourse and Participation in Egypt. Cairo, Egypt: Ford Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- WEF. 2007. The Travel &Tourism Competitiveness Report. Geneva: World Economic Forum. [Google Scholar]

- WEF. 2011. The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report. Edited by Jennifer Blanke and Thea Chiesa. Geneva: World Economic Forum. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The effects of the recent political turmoil are not captured by the data discussed within this report because it was completed by March 2011. |

| 2 | The legal basis for planning in Egypt stems from two different key laws: the Planning Law No. 70/1973, which regulates the process of developing the national socio-economic plan; and the Building Law No. 119/2008, which regulates the process of strategic spatial planning at different levels. |

| 3 | A snowball technique was the most appropriate approach for this research because not all ecotourism stakeholders were appropriate for interview. It was also necessary to ensure that each interviewee had enough experience to provide high-quality information to build an interpretive understanding about ecotourism planning in Egypt. |

| 4 | (PS-14) A reference to the interviewee/s: the acronyms refer to the interviewee groups: EC= Experts & Consultants in ecotourism development or participatory planning, PS = An employee in the Public Sector, NG = A member of NGO boards, LC = A member of the key persons of the Local Communities; and the number refers to the serial number of the interviewee in each group. |

| 5 | They are governmental and non-governmental organisations that are interested in, affected or influence by ecotourism but are located outside the initiatives’ boundaries |

| Critical Factors for Building a Stakeholder Network | Performance of Initiatives | Comments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEDP | ESDNVG | |||

| Did the stakeholder list include all relevant groups? |  |  | Some relevant stakeholder groups such as GOPP & EMUs were excluded from both initiatives | |

| Was there a clear technique for identifying the representative of each group of the internal stakeholder groups? | The representatives of local communities |  |  | In FEDP, they had been based on the survey and interview. In ESDNV, they had been based on the snowball technique by NVTA |

| The representatives of the public sector |  |  | They had been nominated by the agency bosses without any criteria | |

| The representatives of the private sector |  |  | A few eco-lodge owners were involved in FEDP but representatives of hoteliers, tour operators and local guides were involved in ESDNVG | |

| The representatives of NGOs experienced in ecotourism development |  |  | No NGOs with any experience were nominated although several experienced NGOs had conducted activities in the initiatives’ locations | |

| Clear techniques and criteria of the stakeholder analysis |  |  | Stakeholders had not been analysed. The convener considered them all to be at the same level of influence and interest | |

| External stakeholder |  |  | No global or national NGOs except ETF was involved in FEDP | |

| Dialogue between SRs & their parent bodies | public sector |  |  | The dialogues were not good in the normal situation |

| local communities and NGOs |  |  | There was no dialogue | |

Fully achieved

Fully achieved  Partially achieved

Partially achieved  Not achieved. Source: The authors.

Not achieved. Source: The authors.| Diagnosis | Analysis | Development | After Plan Making | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The involvement methods in each phase | Face-to-face interview | Public meeting | Workshop | Questionnaire | Workshop | Public hearing | Awareness-raising programmes |

| Appropriateness at the phases | √ | √ | √ | × | √ | √ | × |

| Sufficiency | × | × | * | × | × | × | × |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kenawy, E.; Osman, T.; Alshamndy, A. What Are the Main Challenges Impeding Implementation of the Spatial Plans in Egypt Using Ecotourism Development as an Example? Soc. Sci. 2017, 6, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6030075

Kenawy E, Osman T, Alshamndy A. What Are the Main Challenges Impeding Implementation of the Spatial Plans in Egypt Using Ecotourism Development as an Example? Social Sciences. 2017; 6(3):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6030075

Chicago/Turabian StyleKenawy, Emad, Taher Osman, and Aref Alshamndy. 2017. "What Are the Main Challenges Impeding Implementation of the Spatial Plans in Egypt Using Ecotourism Development as an Example?" Social Sciences 6, no. 3: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6030075

APA StyleKenawy, E., Osman, T., & Alshamndy, A. (2017). What Are the Main Challenges Impeding Implementation of the Spatial Plans in Egypt Using Ecotourism Development as an Example? Social Sciences, 6(3), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6030075