Abstract

The European Union’s ambition on environmental issues proves to be highly uneven. While it has agreed on stringent binding sustainability objectives in its reforms of the Common Fisheries Policy in 2013, it failed to reach such agreement on its 2030 climate change objectives at almost the same time. How can we make sense of this uneven performance of the European Union (EU) in environmental policy? The present article argues that integrating the multiple streams approach (MSA) with a focus on business power allows a better understanding of the divergence in the EU’s sustainability ambitions across policy fields. Based on this framework, it suggests that Commissioners can be highly influential policy entrepreneurs in the European governance process. Employing a content analysis of relevant documents from the two policy processes as well as interviews with representatives from political as well as non-state actors, the article depicts the suggested dynamics and deduces corresponding lessons for science and politics.

1. Introduction: The Janus Face of the EU’s Environmental Performance

The European Union’s (EU’s) climate change objectives for 2030, which it also submitted to the COP1 in Paris in 2015, were nonbinding and set at levels close to what existing polices already were expected to accomplish (Unbehaun 2016). After an intensive process of negotiation in 2013 and 2014, the EU agreed on a 40% cut in greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels, a 27% share for renewable energy and a 27% target for improvements in energy efficiency in October 2014. In particular, the nonbinding nature of these objectives signaled a departure from the EU’s former stance, reflected for instance in its 2020 climate and energy package, which had included a legally binding 20 percent share for renewable energy. Indeed, given that the EU had previously been perceived as intending to “lead by example” in global climate governance (Oberthür and Dupont 2011), environmental observers deemed its new position a major setback to the pursuit of sustainable development in general and the EU’s environmental ambitions in particular.

In the same period (2011–2013)2, however, the EU decided on a major overhaul of its Common Fisheries Policy (CFP), pursuing four major sustainability goals: the introduction of maximum sustainable yield (MSY) objectives, the introduction of a discard ban, increasing emphasis on regionalization, and the introduction of property rights in the form of individual transferable fishing concessions (TFCs) in efforts to overcome the tragedy of the commons (Peñas Lado 2016, p. 305; see also Leite and Pita 2016; Wakefield 2016).3 These reforms, proposed by the Commission in 2011, were adopted in 2013 despite a decades long failure the EU’s CFP to achieve improvements in the sustainability of its fisheries (Baudron et al. 2010; Barkin and DeSombre 2013; Griffin 2013; Payne 2000). They represented a new and, in the eyes of environmental observers, substantial effort to overcome the complexities still involved in regulating fishing including the shifting of practices towards the fishing of previously unregulated species, challenges resulting from technological conditions as well as lacking data availability, fragmentation and specific market characteristics (Leroy et al. 2016; Moura et al. 2016; Peltier et al. 2016).

How can we make sense of this divergence in the EU’s performance in environmental decision-making? Some observers attribute the change in mood on climate change objectives to the presence of more pressing issues relating to the financial and economic crisis on the EU’s political agenda (Čavoški 2015; Unbehaun 2016). However, this competition for political attention and ambition and potential resulting foci on economic interests should have affected the fisheries agenda as well. So what differences can we detect between the two cases?

The present article uses the multiple streams approach (MSA) with an emphasis on the subcomponent of the balance of interests to contribute to a better understanding why EU environmental ambition varied between the two policy developments. Specifically, the article argues that the context of the globalized political economy makes the balance of interests, one of the subcomponents of the politics stream, the crucial factor in creating policy windows. The presence or absence of cohesive business power, in particular, plays a decisive role. In addition, the article posits that in the EU, this effective presence of business power is mediated by institutional processes and especially the activities of (bureaucratic) norm entrepreneurs and their choices in granting access to business vis-à-vis NGO interests. Applied to the cases of the EU’s climate change targets and CFP reform, thus, the article expects windows of opportunity to have opened due to shifts in decision-making procedures exerting an influence on the balance of power between stakeholder interests as well as due to instances of conflict between major business interests. Such windows of opportunity could then be used by policy entrepreneurs, especially commissioners, to influence the respective policy outputs.

The article’s focus on policy entrepreneurs from within the Commission also links it to the literature on political leadership. Overall, the role of the individual in politics, in general, and in highly institutionalized policy settings, in particular, has received insufficient attention in political science. Building on (March and Olsen 1983) seminal article on “organizational factors in political life” (March and Olsen 1983, p. 734), a number of scholars have inquired into the role of expertise, personal skills and networks, and individual power and influence in political arenas ranging from the municipal to the international level of governance, however (Alexander and Lewis 2015; Foley 2013; Haus et al. 2004; Helms 2012; Partzsch and Fuchs 2012; Rhodes and t’Hart 2014). Rather than conceptualizing political decisions as outcomes of rational processes selecting the best solutions, such approaches emphasize the extent to which the capacities and motivations of individual actors allow them to navigate through complex processes and influence policy outcomes in a specific way. With respect to the EU, scholars have addressed the role of formal leadership resulting from positions such as President of the Commission or Council, as Commissioner or as Chairman, for example (Cini 1997; Tallberg 2006). The present article adds insights on informal leadership that individuals, in this case Commissioners, can develop and use given certain strategies, relationships, and motivations to this literature.

The empirical analysis is based on a content analysis (Mayring 2014) of relevant documents and interviews using MAXQDA. The text corpus includes a broad range of policy documents, such as EU official regulations and green papers, transcriptions from debates in the European Parliament, as well as position papers by stakeholders, specifically NGOs, individual business actors and associations. The analysis also draws insights from 15 interviews that were conducted with members and staff of the European Parliament and the Commission (specifically DG ENER and DG MARE)4, representatives of national governments involved in the relevant policy issues, as well as with non-state actors at the national and international levels, in 2014 and 2015. The interviews were subsequently transcribed and coded as well. Following Mayring’s (Mayring 2014) advice, the emphasis was on inductive methods in the content analysis, continuously refining the starting codes in repeated rounds of coding.5

2. Business Power in a MSA Framework

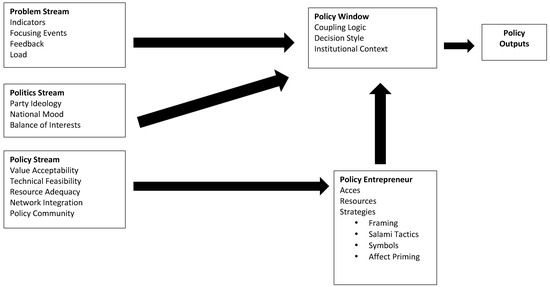

The MSA has been a prominent tool for scholars aiming to understand policy change, ever since its presentation by John Kingdon in Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policy (1984). References to the approach have changed over time from the early description of a “windows of opportunity” approach to today’s shorthand MSA. But the approach has remained popular throughout and indeed is currently experiencing something like a second spring (Cairney and Jones 2016; Herweg 2013; Jones et al. 2016; Rüb 2009). The approach suggests the following: The political process is always characterized by ambivalence in terms of the constant presence of numerous policy options as well as interpretations of problems and solutions (Zahariadis 2008). Against this background of ambivalence, policies will make it unto political agendas or policy decisions will come about when windows of opportunity emerge (Herweg 2015; Kingdon 1984; Zahariadis 1999; 2014; see Figure 1). These windows of opportunity, in turn, exist, when the three “streams”: problem, politics and policy converge. The problem stream captures the need for policy change and can be assessed by indicators of problem pressure as well as influenced by external events such as international negotiations, feedback from other policy fields in term of what works, or load, i.e., the extent to which other problems demand massive attention or not. Changes in the balance of interest, popular opinion, or ideology of the dominant party, in turn, identify relevant factors in the political stream. The policy stream is characterized by questions of normative acceptance, technological feasibility, or resource availability. Policy entrepreneurs, finally, can create and use windows of opportunity to instigate policy change. They can use windows of opportunity for policy change that have come into existence due to new information on a problem being available, a change in (the ideology of the) government or a change in the balance of power among the stakeholders involved in respective policy process, for example. Policy entrepreneurs can also actively create such windows using, for instance, specific framing strategies.

Figure 1.

The multiple streams approach (MSA) (Jones et al. 2016, p. 15).

Over the course of its use as well as in recent survey articles, scholars have also voiced criticism of the approach and its application (Cairney and Jones 2016; Herweg 2015; Jones et al. 2016). While documenting the high number and substantive breadth of studies employing the MSA, they have shown that engagement with the approach often tends to stay at the surface level. Jones et al. (2016) criticizes, in particular, that studies frequently fail to pay sufficient attention to the subcomponents identified as relevant for the three streams. Criticism of the approach also centers on its ambiguity in empirical application and the difficulties of its refutation, which arise from the breadth of its elements, and which exist, especially, if scholars ignore the relevant subcomponents. Last but not least, scholars question the approach’s assumption of the general autonomy of the three streams.

These weaknesses of the approach and its application cannot be eliminated completely. After all, the approach specifies quite a number of subcomponents for each of its five components. Individual studies are not able to address all of them, nor will all of these factors be relevant in individual cases. Moreover, the breadth of the approach is also one of its strengths, enabling the vastness of empirical applications as well as comparisons across cases. Also, Kingdon himself already acknowledges that the three streams may not be completely autonomous. He argues, however, that their dynamics are sufficiently different to treat them as autonomous for analytical purposes (see also Herweg 2015).6 To answer the criticisms, further applications of the approach should ensure improvements in terms of delving below the surface of the five components (Jones et al. 2016). Identifying the most relevant subcomponent(s) and explaining this relevance, furthermore, will help reduce the approach’s criticized ambiguity in empirical analysis. Having said that, the approach will continue to be more inclined towards qualitative rather than quantitative research, even though some attempts at the latter are being made. Thus, it will allow for plausibilizing hypotheses, if empirical analyses take the above aspects into consideration. It will continue to provide challenges for a strict testing and falsification of hypotheses.

In Kingdon’s view, policy change will result especially from the problem or the politics streams. In the politics stream, party ideology and national mood will be particularly relevant for getting issues on the agenda, but the balance of interest subcomponent will be especially influential when it comes to policy decisions. When conceptualizing the subcomponent of the balance of interests, in turn, Kingdon especially refers to access and influence exercised by non-state actors, specifically business and civil society. Thus, when following Zahariadis (2013) recommendation to combine the MSA with other theoretical approaches to gain more explanatory power, it makes sense to look to a power-based governance focus, in particular.

In the current literature on the power of non-state actors in national, regional (including European), and global governance, numerous scholarly and journalistic assessments attribute a domineering role to business (Fuchs 2005, 2013; Klein 2000; Korten 1995; Levy and Newell 2005; Mikler 2017). They document that transnational corporate actors, in particular, wield political power to an unprecedented extent. Corporations lobby and sponsor at the subnational, national, regional, and global levels of governance, shape political agendas there, self-regulate commodity chains, and influence the political process through media campaigns shaping public opinion as well as research funding, thereby strongly affecting the availability of “evidence”. In their expanding role as political actors, they have benefitted from a general climate attributing innovative capacities and efficiency to the market and inefficiency, as well as a lack of expertise, and sluggishness, if not corruption, to governments and bureaucracies. In the era of the globalized political economy, TNCs also have the advantage of their financial and organizational reach, especially when compared to territorially defined and limited state power.

While civil society actors have also expanded their roles, according to the governance literature, it is clear that their political power has not grown on par with that of corporations (Fuchs 2005). Civil society actors’ financial resources pale in comparison, and the asymmetry becomes even more prominent when considering that the largest NGOs tend to attend to numerous policy developments at any one time, while corporations can focus their attention on those issues relevant to their sector (Baumgartner et al. 2009). Furthermore, civil society faces much higher transaction costs, when it comes to organizing. It’s one major source of potential influence, the legitimacy generally attributed to its actors and objectives by the public, can only be effectively exercised in campaigning and shaming exercises if the latter receive sufficient public and accordingly political attention. In a world characterized by the acceleration of all areas of life and information overflow, this situation is increasingly difficult to achieve and possible only for a limited number of issues/actors and time. In addition, one has to be aware that the group of civil society actors also increasingly includes business-sponsored or created NGOs, so called BINGOs, which further weakens civil society’s potential role as a watchdog or defender of broader societal interests against private economic interests (Levy and Newell 2005; Vormedal 2008). However, corporate actors have not only gained in power vis-à-vis civil society and state actors. They also outpower other business actors, specifically small and medium sized businesses, sidestepping traditional business associations and pursuing their political aims in more or less formal or issue-specific clubs and roundtables (Van Apeldoorn 2002; Coen 2007; Greenwood 2011).

Thus, the state of the art of research on the role of business in governance paints a picture of extensive and pervasive corporate power. Berry (1997) describes this situation as a one-sided game, arguing that business is the only remaining enemy of business in the political contest. Indeed, the concept of regulatory capture, once developed to delineate how monopolistic actors’ interests enduringly manage to shape their regulatory environment, specifically the bureaucracies set up to control and regulate the monopolies, probably has to be expanded to the political realm as such, today (Baker 2010; Dal Bo 2006; Laffont and Tirole 1991; Levine and Forence 1990).7

The EU in particular has had to face severe criticisms regarding a disproportionate influence of corporate interests, adding fuel to the rise of Euroscepticism (Fuchs et al. 2017). Studies on business influence in EU governance have documented its predominance in terms of access, staff and financial resources relative to civil society (Adelle and Anderson 2013; Fischer 1997; Fuchs 2005; Grant 2013; Marshall 2010; Rasmussen and Carroll 2014; Ronit and Schneider 2000). They have also linked this predominance to the relative lack of bureaucratic resources vis-à-vis a high complexity of policy issues (in a multinational context), the complex institutional structures of the EU itself, as well as the EU’s traditional focus on economic issues (Cadot and Webber 2002; Chalmers 2013; Knodt et al. 2012; Jordan and Adelle 2013). Scholars even speak of “sponsored pluralism” and “clientilist relationships” to capture the extent of business power in EU governance (Nollert 1997; 2016), and delineate the ineffectiveness of official efforts to reign in lobbying activities by business in Brussels (Greenwood 1998). If Kingdon is right in his claim that shifts in the balance of interests will allow windows of opportunity to open up, one has to ask how such shifts can come about in such a climate of apparently rather stable power asymmetries.

One potential source of interruptions in business’ political influence is captured in Berry’s argument above. Adopting a similar perspective, Falkner’s business conflict approach argues that business will be able to successfully pursue its interests in the political process, when it speaks with a unified voice (Falkner 2008). In cases, in which business actors, especially TNCs, are divided on a policy proposal, however, civil society may prevail. Falkner (2009) uses this business conflict approach to explain the EU’s policy stance on genetically modified organisms. Falkner’s approach thus provides an explanation for a change in the politics stream, allowing for a window of opportunity for reforms to open up, when successfully coupled with the problem and policy streams.

Next to interest constellations among and between relevant actors, institutional settings determine how the balance of interests plays out on the political stage. Except for the case of self-regulation, the mere presence of business power does not determine political outcome. Rather, business power influences political output via politicians and bureaucrats or the public (Fuchs 2005; 2013). In consequence, access to the relevant politicians and bureaucrats and accordingly decisional procedures, which determine which political decision making bodies or bureaucracies are involved in a particular political process, become important.8 In the European Union, this focus on decisional rules is especially relevant, as the involvement of the European Parliament (EP), in particular, in legislative processes has changed in the course of European integration.

It is this question of access, however, which also suggests that the original MSA approach needs to be amended, when it comes to the role of the policy entrepreneur. While Kingdon (1984) originally thought primarily of individuals outside the core decision-making processes in his description of the entrepreneurial role, an individual politician’s or bureaucrat’s room for maneuver with respect to the granting of access to (selected) non-state actors provides them with substantial opportunities to play an entrepreneurial role as well (Beem 2007; Gains and Stoker 2011; Smith 2011). This room for maneuver may exist more in some political systems and processes than in others, but it does exist. In the EU, such a role may be played in particular by Commissioners, especially in the case of divisions within the Commission as well as a lack of clear leadership by the Council (Iusmen 2013; Zahariadis 2013). The potential for a significant role as policy entrepreneur indeed may have been enhanced by institutional developments in the EU intended to grant a stronger voice to the EP, as the directly elected decision-making body. The move to the co-decision procedure, granting the EP decisional rather than just consulting rights in many policy fields has meant that so-called trialogues are often used to negotiate a compromise between the EU’s core institutions. As a member of these trialogues, the Commission, in turn, has been moving closer to achieving decisional power, even if it is formally limited to its agenda-setting role (Thomson 2015). Accordingly, this article argues that the role of Commissioners as policy entrepreneurs in the EU deserves particular attention.

3. Windows of Opportunity in the EU’s Fisheries and Climate Policy

Kingdon suggests focusing on developments in the balance of interest in the politics stream for explanations of political decisions, and, indeed, a change in the balance of interest occurred in the two cases due to a change in the relevant decision making procedures in the European policy process. Following the Lisbon Treaty9, the European Parliament assumed a co-decision making role, as pointed out above. Whereas fisheries reforms, for instance, had been decided by the Council in the past with the EP being granted only an advisory role, the move to the co-decision procedure now meant that the EP actually had (co-)decisional power. The EP, in turn, is traditionally much more accessible to NGOs than the Commission, which has the reputation of granting access predominantly to business interests.10 Herrnson et al. (1998) argue that both leftist and conservative governments (have to) listen to business interests today, with leftist governments also granting access to labor (and environmental) interests, while conservative governments restrict such access severely. Such differences in the granting of access to NGOs are visible at the EP, as well. Given that the EP has been populated by (a sometimes bigger, sometimes smaller share of) members from leftist and green parties, NGOs have been able to gain comparatively more access here. The EP also traditionally sees itself as an environmental voice in European politics (Burns 2013; Rasmussen 2012).

For scholars of European environmental governance, it is thus not surprising, that the EP voted for (more) stringent standards in both cases considered here. In the case of fisheries, the EP shortened timelines and rejected exemptions for the MSY levels and the discard ban, although it did not adopt the proposed TFCs (Engelkamp and Fuchs 2017). In the case of climate change, the EP adopted a non-legislative resolution on the 2030 framework demanding that the policy proposal to be negotiated11 should entail three binding targets: a 40% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels, a 30% share for renewable energy and a 40% energy savings target (European Parliament 2014).

However, the changes in the balance of interest recognizable here was not just a function of a change in institutional procedures. As pointed out above, a strong dominance of business interests in EU governance has been well documented, in general. In the two cases explored here, such dominance tends to exist, as well as, and is further stabilized by historical developments. Fisheries policy used to be part of agricultural policy, and DG AGRI12 has a reputation of especially close ties with the agrarian lobby. Indeed, it is an area notorious for regulatory capture (Wakefield 2016). In consequence, it is not surprising that DG MARE traditionally is heavily influenced if not captured by the fisheries lobby. For the case of climate policy, scholars have documented a similarly strong role that the European industry plays as a stakeholder and lobbyist (Boasson and Wettestad 2013; Fuchs and Feldhoff 2016). This is partly due to the breadth of industrial sectors involved and especially to the role of traditional national champions as well as core motivations behind European integration in the form of the energy, coal, steel and car industries.

Interestingly, however, the dominance of business interests was interrupted or at least moderated, in both cases of interest here. In the case of fisheries, large- and small-scale fisheries as well as the fishing sectors of different member states took different positions on the proposed reforms. The conflict between large and small fisheries is traditional, in so far as they have different technological options and financial resources available (Lloret et al. 2016; Veiga et al. 2016; Villasante et al. 2016). However, in this case, a conflict between the fishing sectors of member countries became apparent. The industrial fishing sectors of Spain or France were highly critical of Commission’s proposal, while the fishing sectors of Denmark and others considered themselves sufficiently competitive and less challenged by it (Engelkamp and Fuchs 2017). This conflict, in turn, translated into a smaller presence of the main fisheries association as a lobbyist in the course of the reform discussions. The discussion will turn to the role of the EP below, but it should be noted at this point that interviewees at the EP noted their surprise at the relatively small lobbying presence of (transnational) economic interests in this case (Engelkamp and Fuchs 2017). Europeche, the association representing the fishermen and the fishing industry in the European Union, also published comparatively fewer political statements on the reforms.

The situation in the context of the climate change negotiations, in turn, was not that different in some ways and yet very different in others. Again, large and small business actors took different positions. Here, the difference is also due to the fact that most of the smaller actors come from the renewable energy sector and new technologies, while the large ones are incumbent to the energy field and include utilities (frequently from the former monopolies), but also car manufacturers and other energy intensive industries such as the steel industry. Still, these conflicts among business interests did not translate into an absence of business in the lobbying process. On the contrary, both individual companies as well as industry associations tried to exercise extensive pressure both at the Commission and the Parliament, as interviewees indicated (see also Fagan-Watson et al. 2015; Fuchs and Feldhoff 2016; Ydersbond 2016).

Indeed, the final outcome of the decision-making process in the two cases differed despite the similar role of the EP, and the analysis shows that this difference can be explained, to a considerable extent, with the different roles the relevant Commissioners played as policy entrepreneurs in terms of granting access to different stakeholders. In the case of fisheries, interviewees stated that Maria Damanaki, the Commissioner of Marine and Fisheries, was very significant in that she opened the process of commenting on the Green Paper of the Commission, which preceded the reform proposal early on, and strongly involved NGOs in the process (Engelkamp and Fuchs 2017). She also pushed for the reform by searching for cooperation with the parliament as well as with the presidency in pursuit of her goals, according to interviewees.

In the case of climate change, Günther Oettinger, the Commissioner for Energy at that time, played the opposite role. He argued for a lower GHG reduction target and especially nonbinding targets for renewables (Bürgin 2015). In this context, Oettinger proved particularly accessible to business interests, as interviewees stated, and NGO and media inquiries have documented close ties between Oettinger and the German car industry as well as large energy utilities, and the oil industry (in particular BP) (Fuchs and Feldhoff 2016; Hall 2012; Neslen 2016). In framing the issue, Oettinger argued that Europe is at a “competitive disadvantage” due to its “reluctance to take risks on offshore oil drilling and tar sands” and its “failure to fully explore its shale gas options” (Neslen 2012). Recent media reports also document that Oettinger is the Commissioner granting most access to business lobbies in the Juncker Commission, according to the records on meetings of Commissioners with lobbyists published by the EU (Becker and Müller 2017).

Clearly, both Commissioners were not acting in isolation or without constraints from their environment. Indeed, both faced opposition in the Commission and Bürgin (2015) has argued that it is particularly in the context of such divisions that individual Commissioners can become particularly strong. In the fisheries case, Commissioner Damanaki was able to overcome opposition to the reforms originating for instance from Michael Barnier, head of (at that time) DG Markt, according to interviewees. In the case of climate change, Commissioner Oettinger was able to gain influence due to divisions within and between the lead DGs, DG ENER and DG CLIMA13, as interviewees stated (see also Bürgin 2015; Fischer 2014). Damanaki was also able to benefit from a very active role of the presidency as well as close collaboration with the EP, specifically Ulrike Rodust, one of the rapporteurs for the proposal (Engelkamp and Fuchs 2017). At the time of the reform negotiations, the Presidency of the Council of the European Union was with Ireland and the Irish Minister for Fisheries, Simon Coveney, strongly involved himself in the process.14 Finally, Damanaki not just collaborated with NGOs, but the NGOs themselves were highly organized grouping together in a campaign called “Ocean 2012”, in which they developed joint lobbying strategies.15 Commissioner Oettinger, in turn, benefited from the lack of leadership on climate issues by the President or the Council in the second Barroso Commission (2009–2014), as interviewees noted (Barnes 2011; Bürgin 2015).

Also, both Commissioners had to negotiate their way through diverging positions of member countries as position papers document and interviewees noted. In the case of fisheries, several member countries with large fishing sectors such as Spain and France were very critical of the proposed reforms, for example, while others such as Denmark and the UK signaled an overall positive reception. In the case of climate change, the Visegrád countries (Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovakia), in particular, tried to prevent ambitious climate targets due to concerns about energy-inefficient economies against the push for stringent binding targets by others (Fischer and Geden 2015).16 In this opposition, they benefitted from the post-Copenhagen skepticism about the future of international climate governance as well as concerns about the consequences of the economic crisis in countries such as Italy and Ireland (Fischer and Geden 2015).

Supporting environmental conditions, thus, can be identified in both cases. Yet, neither the supportive presidency nor the NGOs, by themselves, would likely have been able to achieve the adoption of the desired fisheries reforms without Commissioner Damanaki’s attention to civil society interests and inclination to collaborate with supportive state and non-state actors. Similarly, business interests opposing stringent targets in the case of climate change were able to strengthen opposition to binding targets because of their close contacts with Commissioner Oettinger. The analysis of the two cases thus suggests that Commissioners can use windows of opportunity in terms of an interruption of the balance of interest to improve or restrict access by different stakeholders, thereby strategically influencing policy processes.

In explaining the difference in outcomes, the present analysis has concentrated on developments in the politics stream and the role of policy entrepreneurs. Could differences in the policy stream provide a similarly convincing explanation? Were perhaps new ideas on policies and instruments becoming dominant in the fisheries policy stream, but not in the climate policy stream? It seems unlikely that was the case. Even if climate science is more complex and the overall dynamics and implications are less understood, concrete ideas about the necessary direction of policies as well as policy targets and instruments have existed in both fields for a considerable amount of time. Moreover, a better comprehension of fisheries dynamics would not explain why the EU’s CFP has been a failure for so long. Thus, it seems more plausible that the conditions in the politics stream used and managed by the Commissioners as policy entrepreneurs led to specific ideas and instruments from the policy stream being chosen.

Neither of the Commissioners or the other actors involved in the two policy processes completely achieved their goals, of course. In Commissioner Damanaki’s case, she had to accept the rejection of an implementation of TFCs, while the MSY and discard targets ended up even more stringent and with earlier targets of full implementation than originally proposed, however. In Commissioner Oettinger’s case, he eventually had to accept the 40% GHG target suggested by Barroso as a compromise. However, he was able to prevent the targets from being binding as well as to lower targets on renewable energies and energy efficiency. The analysis thus does not aim to suggest that Commissioners are the new dictators, able to determine policy output single-handedly. However, it indicates that Commissioners as policy entrepreneurs can exercise considerable influence on such output.

4. Conclusions

Summing up, this article investigated policy change in the EU’s fisheries and climate policies. Specifically, it analyzed why EU decisions on the CFP and climate change objectives went in opposite directions from an environmental perspective, in the same period of time. For the CFP, the EU adopted its strongest pro-sustainability oriented policy so far, agreeing on maximum sustainable yield targets, a discard ban and related measures. With respect to climate change, the EU adopted nonbinding emission reduction targets, contrary to its tradition here. The article integrated a focus on business power in the MSA and argued that a change in the balance of interests in combination with Commissioners assuming the role of policy entrepreneurs provides an explanation for this divergence in EU environmental policy output. Conducting a content analysis of policy documents and interview transcripts, finally, the article identified relevant changes in institutional procedures as well as business conflict and linked them to windows of opportunity, which the two relevant Commissioners, Maria Damanaki and Günther Oettinger, then used in opposite environmental directions.

What can we learn from this analysis? In terms of lessons for science, the inquiry documented that the MSA indeed continues to be a useful tool for understanding opportunities for policy change and the dynamics surrounding those. The findings also support the argument that scholars need to study especially the politics stream’s subelement of the balance of interest. As numerous studies have shown, political contests in the era of the globalized political economy are characterized by a presence of enormous political power by business actors. Accordingly, it should be very promising to look for interruptions in power asymmetries between business and civil society when trying to explain policy change. Moreover, for scholars of EU governance, the findings highlight the crucial role that Commissioners can play as policy entrepreneurs; their ties to stakeholders clearly deserve more attention.

These insights also present the core link to lessons for politics. The importance of the individual Commissioners, highlighted by this study, contrasts with the attention their appointment receives in the political process and public debate. The democratic legitimacy of these appointments rests on the election of national governments proposing Commissioners as well as the rights of the EP to reject them (but only as a whole). In the past, the EP has rarely acted decisively on this decision, and tended to shy away from confrontation, given the size of the hurdle. Governments, in turn, have sometimes used Brussels to provide for party members who have lost or are in danger of losing their national political functions. From the perspective of democratic legitimacy and especially in the context of rising Euroscepticism, these practices should be rethought. A related lesson for politics arising from this study is the need to attend to the question of business dominance, if not of the regulatory capture of the political process in general, especially at the EU. Indeed, the Juncker Commission (2014–2019) is probably the primary example for regulatory capture in the EU and thereby also a major contributor to rising Euroscepticism (Fuchs et al. 2017). The priority it attaches to growth and competitiveness, its reduction in the number of Commissioners with environmental portfolios as well as in the influence of DG Environment, which interviewees noted, is clearly detrimental to sustainability objectives (Delreux and Happaerts 2016; Fuchs and Feldhoff 2016; Steinebach and Knill 2016). Thus, reeling in business influence is highly necessary in terms of popular support for the EU as much as in terms of the sustainability challenges facing humankind. In the meantime, it will be important to use windows of opportunity wherein business dominance is interrupted.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful for research support by S. Engelkamp and A. Graf, who also conducted the majority of interviews, as well as grant FU 434/5-1 by the German Research Association (DFG).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Adelle, Camilla, and Jason Anderson. 2013. Lobby groups. In Environmental Policy in the EU. Edited by Andrew Jordan and Camilla Adelle. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, Damon, and Jenny Lewis, eds. 2015. Making Public Policy Decisions: Expertise, Skills and Experience. Milton Park: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Andrew. 2010. Restraining regulatory capture? Anglo-America, crisis politics and trajectories of change in global financial governance. International Affairs 86: 647–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkin, Samuel, and Elisabeth DeSombre. 2013. Saving Global Fisheries. Reducing Fishing Capacity to Promote Sustainability. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, Pamela. 2011. The role of the Commission of the European Union. In The European Union as a Leader in International Climate Change Politics. Edited by Rüdiger Wurzel and James Connelly. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Baudron, Alan, Clara Ulrich, Rasmus Nielsen, and Jesper Boje. 2010. Comparative evaluation of mixed-fisheries effort-management system based on the Faroe Islands example. ICES Journal of Marine Science 67: 1036–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, Frank, Jeffrey Berry, Marie Hojnacki, David Kimball, and Beth Leech. 2009. Lobbying and Policy Change. Who Wins, Who Loses, and Why. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, Markus, and Peter Müller. 2017. Bei Oettinger gehen die Wirtschaftslobbyisten ein und aus. Available online: http://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/soziales/eu-kommission-empfaengt-regelmaessig-lobbyisten-aus-wirtschaft-a-1144911.html (accessed on 28 April 2017).

- Beem, Betsi. 2007. Co-Management from the Top? The Roles of Policy Entrepreneurs and Distributive Conflict in Developing Co-Management Arrangements. Marine Policy 31: 540–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, Jeffrey. 1997. The Interest Group Society. New York: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Boasson, Elin, and Jørgen Wettestad. 2013. EU Climate Policy. Industry, Policy Interaction and External Environment. Farnham: Asghate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bürgin, Alexander. 2015. National binding renewable energy targets. Journal of European Public Policy 22: 690–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, Charlotte. 2013. The European Parliament. In Environmental Policy in the EU. Actors, Institutions and Processes. Edited by Andrew Jordan and Camilla Adele. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cadot, Oliver, and Douglas Webber. 2002. Banana Splits: Policy Process, Particularistic Interests, Political Capture, and Money in Transatlantic Trade Politics. Business and Politics 4: 5–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairney, Paul, and Michael Jones. 2016. Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Approach. What Is the Empirical Impact of this Universal Theory? Policy Studies Journal 44: 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čavoški, Aleksandra. 2015. A post-austerity European Commission. Environmental Politics 24: 501–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, Adam. 2013. Trading Information for Access. Journal of European Public Policy 20: 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cini, Michelle. 1997. The European Commission: Leadership, Organization and Culture in the EU Administration: Leadership, Organisation and Culture in the EU Administration. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coen, David. 2007. Empirical and theoretical studies in EU lobbying. Journal of European Public Policy 14: 333–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Bo, Ernesto. 2006. Regulatory Capture. A Review. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 22: 203–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delreux, Tom, and Sander Happaerts. 2016. Environmental Policy and Politics in the European Union. Basingstoke: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Engelkamp, Stephan, and Doris Fuchs. 2017. Political Contestation and the Reform of European Fisheries Policy. ZIN Discussion Paper 01/2017. Münster: University of Muenster. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. 2014. European Parliament Resolution of 5 February 2014 on a 2030 Framework for Climate and Energy Policies (2013/2135(INI)). Available online: www.europarl.europa. eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//NONSGML+TA+P7-TA-2014-0094+0+DOC+PDF+V0//EN (accessed on 7 July 2016).

- Fagan-Watson, Ben, Bridget Elliott, and Tom Watson. 2015. Lobbying by Trade Associations on EU Climate Policy. London: Policy Studies Institute, Available online: http://miljo-utveckling.se/files/2015/04/PSI-Report_Lobbying-by-Trade-Associations-on-EU-Climate-Policy.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2016).

- Falkner, Robert. 2008. Business Power and Conflict in International Environmental Politics. Basingstoke: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Falkner, Robert. 2009. The Troubled Birth of the Biotech Century. In Corporate Power in Agrifood Governance. Edited by Jennifer Clapp and Doris Fuchs. Cambridge: MIT. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Klemens. 1997. Lobbying und Kommunikation in der Europäischen Union. Berlin: Berlin Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Severin. 2014. The EU’s New Energy and Climate Policy Framework for 2030. Implications for the German Energy Transition. SWP Comments 55. Available online: www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/comments/2014C55_fis.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2016).

- Fischer, Severin, and Oliver Geden. 2015. EU Climate Policy—Time to come down to earth. Energypost. May 21. Available online: http://www.energypost.eu/eu-climate-policy-time-come-earth/ (accessed on 7 July 2016).

- Foley, Michael. 2013. Political Leadership: Themes, Contexts, and Critiques. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, Doris. 2005. Understanding Business Power in Global Governance. Baden-Baden: Nomos. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, Doris. 2013. Theorizing the Power of Global Companies. In Handbook of Global Companies. Edited by John Mikler. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, Doris, and Berenike Feldhoff. 2016. Passing the Scepter, not the Buck. Long Arms in EU Climate Politics. Journal of Sustainable Development 9: 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, Doris, Tobias Gumbert, and Bernd Schlipphak. 2017. Euroscepticism and Big Business. In The Routledge Handbook of Euroscepticism. Edited by Benjamin Leruth, Nicholas Statin and Simon Usherwood. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gains, Francesca, and Gerry Stoker. 2011. Special Advisers and the Transmission of Ideas from the Policy Primeval Soup. Policy & Politics 39: 485–98. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, Stefanie. 2005. Europäische Governance. Marburg: Tectum. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Wyn. 2013. Business. In Environmental Policy in the EU. Edited by Andrew Jordan and Camilla Adelle. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, Justin. 1998. Regulating Lobbying in the European Union. Parliamentary Affairs 51: 587–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, Justin. 2011. Interest Representation in the European Union. Basingstoke: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, Liza. 2013. Good Governance, Scale and Power. A Case Study of North Sea Fisheries. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Marc. 2012. Oettinger tells Volkswagen he relaxed new CO2 targets. EurActiv. October 12. Available online: http://www.euractiv.com/section/transport/news/oettinger-tells-volkswagen-he-relaxed-new-co2-targets/ (accessed on 4 July 2017).

- Haus, Michael, Hubert Heinelt, and Murray Stewart, eds. 2004. Urban Governance and Democracy: Leadership and Community Involvement. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Helms, Ludger, ed. 2012. Comparative Political Leadership. Amsterdam: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Herrnson, Paul, Ronald Shaiko, and Clyde Wilcox. 1998. The Interest Group Connection. Electioneering, Lobbying, and Policymaking in Washington. Chatham: Chatham House Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Herweg, Nicole. 2013. Der Multiple-Streams-Ansatz—Ein Ansatz, dessen Zeit gekommen ist? Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 7: 321–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herweg, Nicole. 2015. Multiple Streams Ansatz. In Handbuch Policy Forschung. Edited by Georg Wenzelburger and Raimund Zolnhöfer. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. [Google Scholar]

- Hüller, Thorsten. 2010. Playground or Democratisation? Swiss Political Science Review 16: 77–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iusmen, Ingi. 2013. Policy entrepreneurship and Eastern enlargement. The case of EU children’s rights policy. Comparative European Politics 11: 511–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Michael, Holly Peterson, Jonathan Pierce, Nicole Herweg, Amiel Bernal, Holly Lamberta Raney, and Nikolaos Zahariadis. 2016. A River Runs Through It. A Multiple Streams Meta-Review. Policy Studies Journal 44: 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, Andrew, and Camilla Adelle, eds. 2013. Environmental Policy in the EU. Actors, Institutions and Processes. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon, John. 1984. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. New York: Harper Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Naomi. 2000. No Logo: Taking Aim at the Brand Bullies. Toronto: Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Knodt, Michèle, Christine Quittkat, and Justin Greenwood, eds. 2012. Functional and Territorial Interest Representation in the EU. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Korten, David. 1995. When Corporations Rule the World. West Hartford: Kumarian Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laffont, Jean-Jacques, and Jean Tirole. 1991. The Politics of Government Decision-Making. A Theory of Regulatory Capture. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 106: 1089–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, Laura, and Cristina Pita. 2016. Review of participatory fisheries management arrangements in the European Union. Marine Policy 74: 268–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, Antonia, Florence Galletti, and Christian Chaboud. 2016. The EU restrictive trade measures against IUU fishing. Marine Policy 64: 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, Michael, and Jennifer Forence. 1990. Regulatory Capture, Public Interest, and the Public Agenda: Toward a Synthesis. Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 6: 167–98. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, David, and Peter Newell, eds. 2005. The Business of Environmental Governance. Cambridge: MIT. [Google Scholar]

- Lloret, Jossep, Ian Cox, Henrique Cabral, Margarida Castro, Toni Font, Jorge Gonçalves, Ana Gordoa, Ellen Hoefnagel, Sanja Matic-Skoko, Eirik Mikkelsen, and et al. 2016. Small-scale coastal fisheries in European Seas are not what they were. Ecological, social and economic changes. Marine Policy. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, James, and Johan Olsen. 1983. The New Institutionalism: Organizational Factors in Political Life. American Political Science Review 78: 734–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, David. 2010. Who to Lobby and When. European Union Politics 11: 553–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, Philip. 2014. Qualitative Content Analysis. Klagenfurt: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Mikler, John. 2017. The Political Power of Corporations. Cambridge: Polity Press, forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, Pedro. 2016. Managing Scarce Resources and Sensitive Ecosystems. Assessing the Role of CFP in the Development of Portuguese Fisheries. Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management 18: 1650022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, Teresa, António Fernandes, Ricardo Alpoim, and Manuela Azevedo. 2016. Unravelling the dynamics of a multi-gear fleet—Inputs for fisheries assessment and management under the Common Fisheries Policy. Marine Policy 72: 219–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neslen, Arthur. 2012. EU energy chief warms to offshore oil and shale gas. EurActiv. July 19. Available online: http://www.euractiv.com/section/climate-environment/news/eu-energy-chief-warms-to-offshore-oil-and-shale-gas/ (accessed on 28 July 2017).

- Neslen, Arthur. 2016. EU dropped climate policies after BP threat of oil industry ‘exodus’. The Guardian. April 20. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/apr/20/eu-dropped-climate-policies-after-bp-threat-oil-industry-exodus (accessed on 28 April 2017).

- Nollert, Michael. 1997. Verbändelobbying in der Europäischen Union. In Verbände in Vergleichender Perspektive. Edited by Ulrich von Alemann and Bernhard Weβels. Berlin: Sigma. [Google Scholar]

- Nollert, Michael. 2016. High-level Lobbying und Agenda Setting. In Wie Eliten Macht Organisieren. Edited by Björn Wendt, Marcus Klöckner, Sascha Pommrenke and Michael Walter. Hamburg: VSA. [Google Scholar]

- Oberthür, Sebastian, and Claire Dupont. 2011. The Council, the European Council and international climate policy. In The European Union as a Leader in International Climate Change Politics. Edited by Rüdiger Wurzel and James Connelly. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Partzsch, Lena, and Doris Fuchs. 2012. Philanthropy: Power with in International Relations. Journal of Political Power 5: 359–76. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, Dexter. 2000. Policy Making in Nested Institutions. Explaining the Conservation Failure of the EU’s Common Fisheries Policy. Journal of Common Market Studies 38: 303–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltier, Hélène, Matthieu Authier, Rob Deaville, Willy Dabin, Paul Jepson, Olivier van Canneyt, Pierre Daniel, and Vincent Ridoux. 2016. Small cetacean bycatch as estimated from stranding schemes. The common dolphin case in the northeast Atlantic. Environmental Science & Policy 63: 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñas Lado, Ernesto. 2016. The Common Fisheries Policy. The Quest for Sustainability. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Potts, Tavis, Cristina Pita, Tim O’Higgins, and Laurence Mee. 2016. Who cares? European attitudes towards marine and coastal environments. Marine Policy 72: 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, Maja. 2012. Is the European Parliament still a policy champion for environmental interests? Interest Groups and Advocacy 1: 239–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, Anne, and Brendan Carroll. 2014. Determinants of Upper-Class Dominance in the Heavenly Chorus. British Journal of Political Science 44: 445–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, Roderick, Arthur William, and Paul t’Hart, eds. 2014. The Oxford Handbook of Political Leadership. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ronit, Karsten, and Volker Schneider, eds. 2000. Private Organizations in Global Politics. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rüb, Friedbert. 2009. Multiple-Streams-Ansatz: Grundlagen, Probleme und Kritik. In Lehrbuch der Politikfeldanalyse 2.0. Edited by Klaus Schubert and Nils Bandelow. München: Oldenbourg Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Salomon, Markus, Till Markus, and Miriam Dross. 2014. Masterstroke or Paper Tiger. The Reform of the EU’s Common Fisheries Policy. Marine Policy 47: 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Martin John. 2011. Tsars, leadership and innovation in the public sector. Policy & Politics 39: 343–59. [Google Scholar]

- Steinebach, Yves, and Christoph Knill. 2016. Still an Entrepreneur? Journal of European Public Policy. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallberg, Jonas. 2006. Leadership and Negotiation in the European Union. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Teffer, Peter. 2014. Leaked papers show EU disagreement on climate goals. EU Observer. October 16. Available online: https://euobserver.com/news/126112 (accessed on 10 July 2016).

- Thomson, Robert. 2015. The distribution of power among the institutions. In European Union. Edited by Jeremy Richardson and Sonia Mazey. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Unbehaun, Sarah. 2016. A Façade of Unity. The EU as a Global Climate Policy Leader. Transatlantic Policy Symposium 2016. Available online: http://tapsgeorgetown.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Sarah-Unbehaun-EU-climate-and-energy-divisions.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2016).

- Van Apeldoorn, Bastian. 2002. The European Round Table of Industrialists: Still a Unique Player? In The Effectiveness of EU Business Associations. Edited by Justin Greenwood. Basingstoke: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Veiga, Pedro, Cristina Pita, Mafalda Rangel, Jorge Gonçalves, Aida Campos, Paul Fernandes, Antonello Sala, Massimo Virgili, Alessandro Lucchetti, and et al. 2016. The EU landing obligation and European small-scale fisheries. What are the odds for success? Marine Policy 64: 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villasante, Sebsatian, Graham Pierce, Cristina Pita, César Guimeráns, João Garcia Rodrigues, Manel Antelo, and José MaríaDa Rochah. 2016. Fishers’ perceptions about the EU discards policy and its economic impact on small-scale fisheries in Galicia (North West Spain). Ecological Economics 130: 130–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vormedal, Irja. 2008. The Influence of Business and industry NGOs in the Negotiation of the Kyoto Mechanisms. Global Environmental Politics 8: 36–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, Jill. 2016. Reforming the Common Fisheries Policy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Ydersbond, Inga. 2016. Where Is Power Really Situated in the EU? Complex Multi-Stakeholder Negotiations and the Climate and Energy 2030 Targets. FNI Report 3/2016. Lysaker: Fridtjof Nansen Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Kevin. 2012. Transnational regulatory capture? An empirical examination of the transnational lobbying of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Review of International Political Economy 19: 663–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahariadis, Nikolaos. 1999. Ambiguity, Time and Multiple Streams. In Theories of the Policy Process. Edited by Paul Sabatier. Boulder: Westview. [Google Scholar]

- Zahariadis, Nikolaos. 2008. Ambiguity and Choice in European Public Policy. Journal of European Public Policy 15: 514–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahariadis, Nikolaos. 2013. Building Better Theoretical Frameworks of the European Union’s Policy Process. Journal of European Public Policy 20: 807–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zahariadis, Nikolaos. 2014. Ambiguity and Multiple Streams. In Theories of the Policy Process. Edited by Paul Sabatier and Christopher Weible. Boulder: Westview. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | In the context of the United Nations Framework on Climate Change, all states that are parties to the convention meet regularly at the Conference of the Parties (COP) to negotiate agreements and targets. |

| 2 | The process had been launched with a Green Paper, opening a period of consultation in 2009. |

| 3 | Of course, the outcome and impact of the reforms are yet to be determined. A range of factors, such as the member states’ continued authority over implementation, may well reduce the potential improvements in the sustainability of the European fisheries intended by the reform (Monteiro 2016; Salomon et al. 2014; Villasante et al. 2016). The present paper concentrates on the output of the policy process, however. Also, similar questions regarding outcome and impact exist with respect to the EU’s climate targets. |

| 4 | The European Commission is the core administrative organ of the European Union. Its tasks include the development of new legislative proposals and the overseeing of implementation processes. The Commission is composed of Directorates General (DGs), which each oversees and works on a specific field of expertise. In the context of the cases studied here, DG Energy (known as DG ENER) and DG Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (known as DG MARE), respectively, were the most active entities in the Commission. |

| 5 | Of course, an analysis of official documents and interviews provides only indirect evidence of certain dynamics, specifically the motivations and influence of actors and thus allows me to plausibilize rather than stringently test hypotheses. In the absence of a comprehensive and reliable documentation of all lobbying efforts (in volume, contents, and structural context), nothing else is possible. The question of interactions between politicians and/or bureaucrats and non-state actors and their implications is too crucial, however, for scholars to ignore. |

| 6 | Thus, the politics stream is characterized by bargaining and the policy stream by persuasion, according to Kingdon. |

| 7 | See, however, (Young 2012) argument that we need a more nuanced analysis of regulatory capture in global finance governance. |

| 8 | This shows that the subcomponents identified by the MSA model are not completely independent of each other as well, but are conceptualized that way for analytical purposes, only. |

| 9 | Officially: “The Treaty of Lisbon amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty establishing the European Community”, signed, December 13, 2007, effective since December 1, 2009. |

| 10 | Scholars have documented the failure of the Commission to adequately consider civil society voices even in cases in which a formal process for gathering those had been established (Geiger 2005; Hüller 2010). |

| 11 | As pointed out above, the Commission has the task of developing proposals, in the EU’s policy process, which Council and, if the Co-Decision procedure applies, the EP then vote upon. |

| 12 | Directorate General for Agriculture and Rural Development. |

| 13 | Directorate General for Climate Action. |

| 14 | Interviewees highlighted that he repeatedly went to Brussels and Strasbourg to chair meetings and push for agreement (Engelkamp and Fuchs 2017). |

| 15 | Note, however, that public awareness of and concern about maritime issues tends to be below those for other environmental issues, across countries (Potts et al. 2016). |

| 16 | See also (Teffer 2014). |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).