Linking Group Theory to Social Science Game Theory: Interaction Grammars, Group Subcultures and Games for Comparative Analysis

Abstract

:1. Group Theory, Game Theory, and Their Interlinkage: An Overview

1.1. Introduction

1.2. Rule Regimes, Group Properties (Relations/Structures), and Group Differentiation

1.2.1. Rule Regimes and Social Relations/Structures

1.2.2. Universal Interaction Grammars8

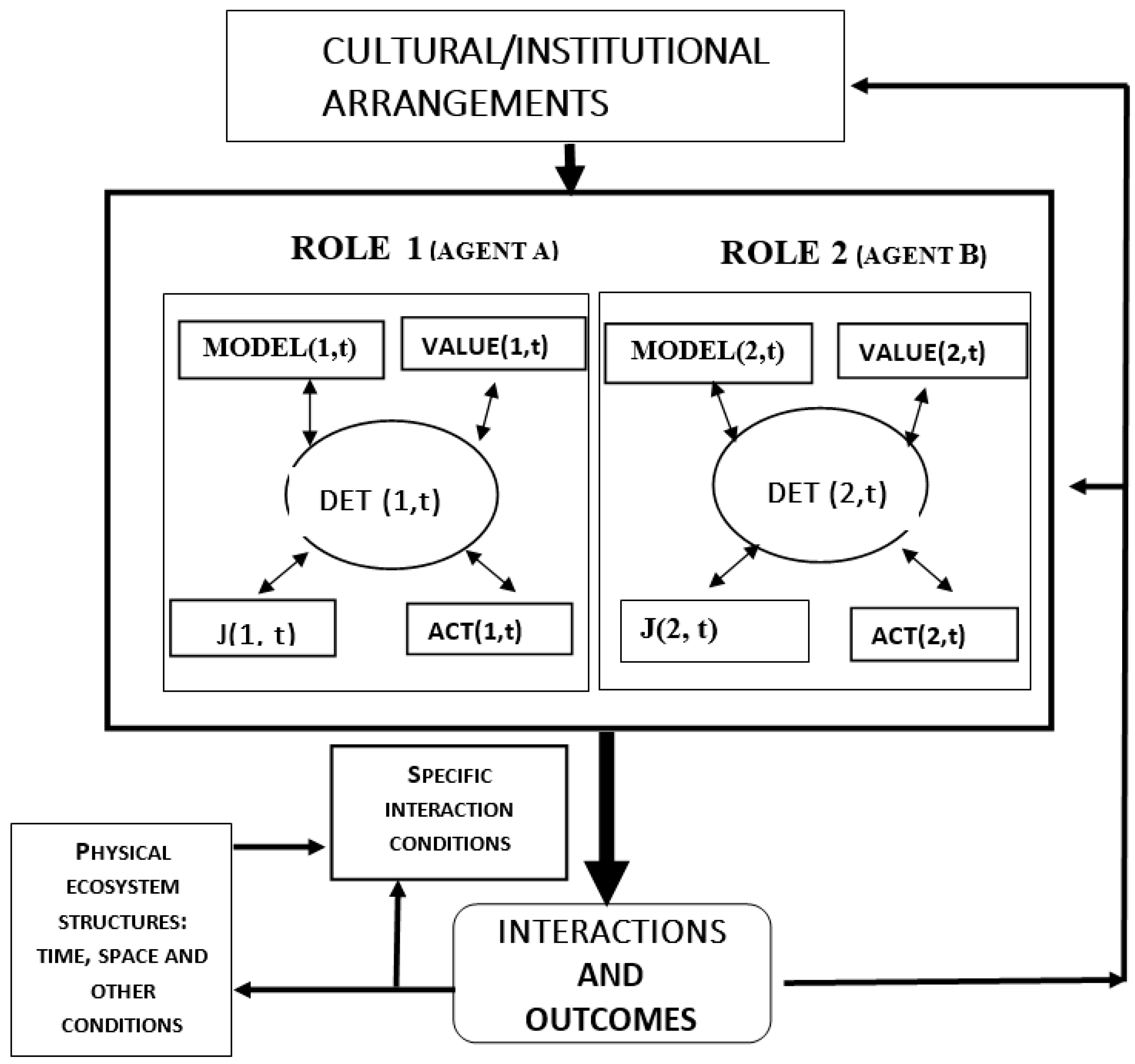

1.3. Social Science Game Theory in a Nutshell (SGT)16

- -

- Established relationships even influence actors’ selection of interaction situations, or their avoidance of certain situations, or their adjusting or transforming certain situations so that they are compatible with—or match—the relationships and normative order. For example, a group of research colleagues often restructure a meeting place to be more like a seminar for peers rather than a lecture hall (unless, of course, a lecture is planned).

- -

- When a negative interaction situation cannot be controlled or restricted by the participants, they try to “act under the circumstances” in ways appropriate to their cooperative relationships. Unless one or more decide to give up on a relationship, and bracket it. In other words, they may play the “situational” game as it should be played and bracket their friendship or kinship while the game—with its rules diverging from friendship or kinship relations—is being played.

- -

- Earlier (Burns and Roszkowska 2005, 2006), we modeled how the norms of asymmetrical relationships, such as status relationships based on gender, education, ethnicity, professional association (including military, hospital and educational systems), indicate appropriate and equilibrium interaction behavior and outcomes, namely asymmetrical ones. Zelizer (2012) speaks in terms of the actors “conducting relational work” in order to select or produce interactions and outcomes that are compatible with the relationship—they try to find and reproduce patterns that confirm their sense of what the relationship is all about and try to maintain these patterns or practices. In general, actors try to match their interactions, for instance, economic transactions, with the “meaning of the particular relation”. “Relational work consists in creating viable matches among those meaningful relations, transactions, and media”. She continues, “In Purchase of Intimacy (2007) I note that relational work becomes especially consequential when relations resemble others that have significantly different consequences for the parties. In such cases, people make extra efforts to distinguish the relations and mark their boundaries: To the extent that two relations are easily confused, weighty in their consequences for participants, and/or significantly different in their implications for third parties, participants and third parties devote exceptional effort to marking what the relationship is and is not; distinctions among birth children, adopted children, foster children, and children taken in for day care, for instance, come to matter greatly for adult-child relations, not to mention relations to the children’s other kin”.

2. Elaboration of Group and Game Theories and Their Interrelationships

2.1. Group Differentiation According to Group Rule Configurations

2.2. Group Rule Configurations and Differentiation among Groups

2.3. The Coherence of Group Rule Configurations

2.4. Compatibility of Multiple Group Regimes

2.5. Group Prioritization with Respect to Coherence: Issues of Identity, Social Order, and Its Impact on Performance and Group Outputs

- Identity and boundary control. If the group is highly concerned about identity issues and, in particular, distinguishing itself from other group(s), then it tries to assure coherence and implementability of recruitment, participation, and performance rules in the rule configuration relating directly (or even indirectly) to group identity. Coherency failure results in ambiguous and confusing identity, status, and performance—for example, instances of group boundary transgression and “pollution”. Performances are required to be compatible with or to realize identity.

- The boundary between “the sacred and the profane”. In areas of sacrality, a group tries to assure coherence of rule configuration(s) relating to distinctions between the sacred and the profane, and securing the appropriate behavior in relation to these distinctive domains of social action. Incoherence or ambiguity of rules leads to risks of dangerous transgressions and pollution of a sacred area. Violation of rules and rituals that play an important part in distinguishing the sacred from the profane is responded to with fury and even violence.

- Demand for highly effective collective performance. In the cases (see Table 3), the military,51 the business unit,52 and the terrorist group try to assure coherence among rules so as to assure effective group coordination and collective performance—as they relate to key concerns or purposes of such groups.53

- Risky technologies and materials. A group (concerned about its own safety) and/or the external legal and institutional environment demands are oriented to high control of, for instance, risky technology (nuclear power plant, commercial aircraft, high speed trains, etc.), dangerous materials such as hazardous chemicals and explosives. Therefore, it tries to assure appropriate and coherent rules relating directly or indirectly to effective deployment and controlled handling of the risky technologies and materials.

3. Linking Group Theory to Social Science Game Theory

3.1. Universal Group Games

- (a)

- Group collective problem-solving. This concerns non-routine problems which calls for judgment and decision-making in dealing with them. Questions such as the following confront the group: what is the problem? How to deal with it? The problem(s) may be internal ones arising in connection with new members, new leadership, new technologies, changes in resource levels, growth in group size or scale. Or, changes in key external conditions or external agents evokes group decision processes. For instance, external agent(s) on whom the group is dependent (“resource dependency”) increase demands in exchange for the resource provided or make additional demands. The group must decide how to react to the demands, for instance, whether or not to accept the demands. Negotiation may ensue, requiring further group decision-making.Radical material change taking place in the environment—flooding, an emerging volcano, or declining food resources (as a result of overhunting or soil salinization) forces the group to abandon the area in order to survive. The group or its leadership makes decisions about departure and where to migrate to.

- (b)

- One universal type of group problem-solving is non-routine conflict-resolution (internal and/or external conflict). Internal conflicts may arise in connection with rivalry among leaders or ongoing hostility between some group members or subgroups. Or, it may involve conflict with external agents. Some sroups establish procedures or mechanisms to resolve non-routine conflicts such as adjudication, negotiation, and democratic vote, which they activate in such situations.

- (c)

- Games about changing rules, policies, paradigms. Functioning or ongoing groups sooner or later engage in games that relate to non-routine changes in group rules and policies as well as entire paradigms. That is, the change is not automatic or algorithmic but involves deliberation and choice. In these situations, there is often a vigorous situational “politics” in the group games to establish, maintain, and change social rules and complexes of rules (in groups as well as organizations and communities). Actors may disagree about, and struggle over, the definition of the situation, and thus over which rule system(s) should apply or how the rule system(s) should be interpreted or applied in the situation. Actors in any group tend to encounter resistance from others when they deviate from or seek to modify established important group rules—or even merely talk about such actions. This sets the stage for games of exercising power either to enforce rules or to resist them, or to introduce new ones. Pressure to change rules and rule complexes may also come from outside the group, for instance external legal requirements or pressures from powerful external agents. Typically, in these cases, the group will try to decide whether to accept the change requirement or oppose it, or accept it “frontstage” but operate clandestinely (“backstage”) in opposition to the external demands.

- (d)

- Games about internal and external governance. All functioning groups have such games. These are particularly observable in the case of non-routine deviance or breakdown in group order. Some groups have stringent governance, multiple internal controls such as in our illustrative military and terror groups concerning internal behavior such as required manifestations of loyalty and explicit adherence to key norms and role patterns.

- (e)

- Games of Secrecy. All groups have secrets and maintain a frontstage public position as distinct from a backstage group or subgroup position. Much concealment and deception is routine, automatic. Foror non-routine situations, however, there are well-recognized games and strategies around frontstages, back-stages, and their interconnections (Goffman 1959, 1974). Some groups emphasize or exaggerate the distinction between frontstage and backstage, especially if their performance, their freedom, their sustainability depends on concealing illegal activities, inappropriate bership, and forbidden resources and technologies This is particularly important for spy groups or groups engaged in illegal activities (e.g., criminal groups).

3.2. Differentiation in Rule Configurations and the Definition and Regulation of Games

4. Concluding Remarks

- (1)

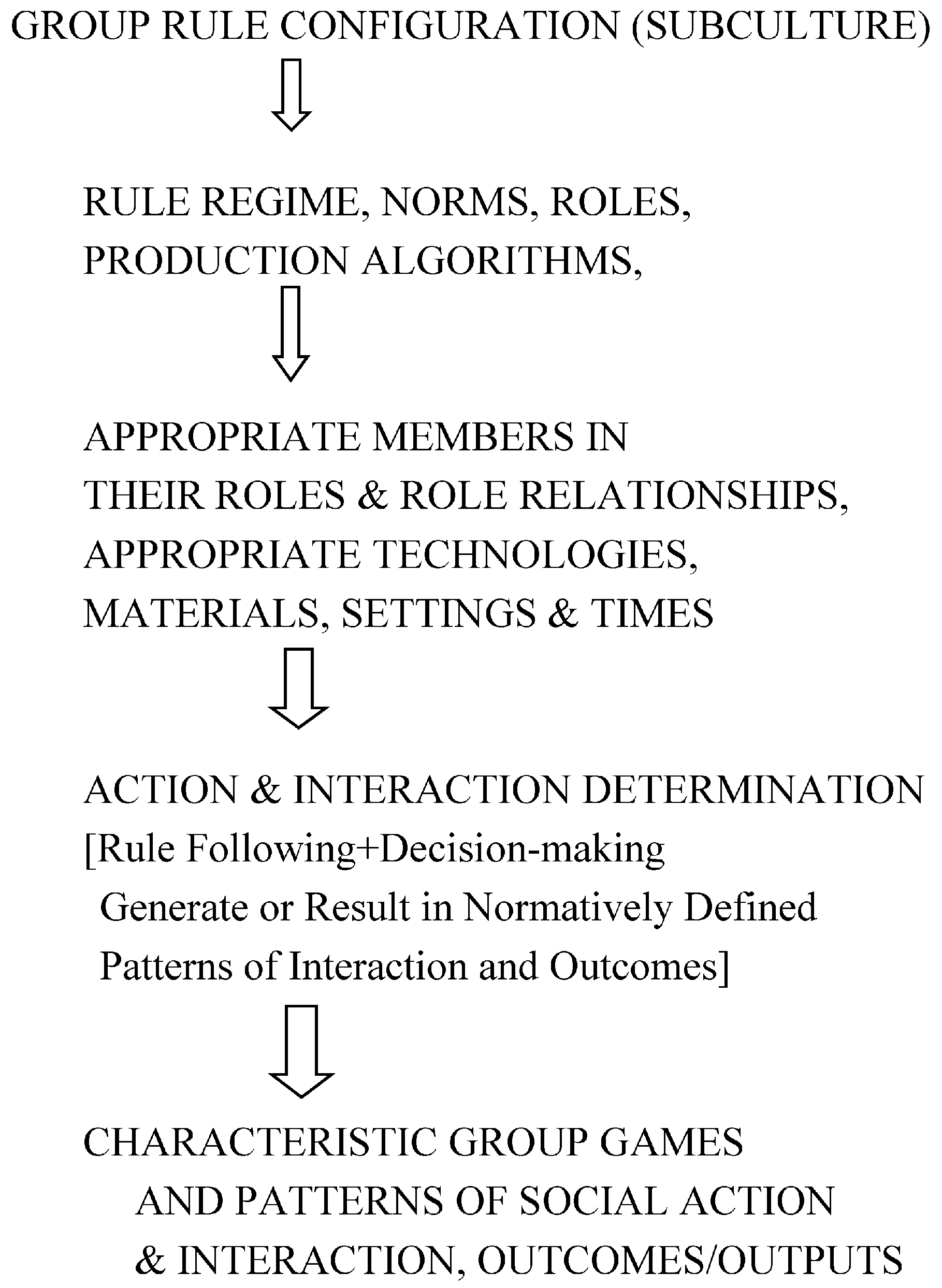

- The universal interaction grammar specifies the finite rule categories for all ongoing groups, communities, and organizations. These make up a meta-system. The specific empirical rule content of each and all categories for each group defines the characteristic rule configuration (a specific group “subculture”). That is, a configuration provides key game “rules and rule complexes” for each group. This is the linkage based on social rule system theory between group theory and social science game theory, as we have suggested here.

- (2)

- The group configuration is then a complex of norms and other rules providing a major part of the particular socio-cultural character and “rules of games” (game structures) for the group. Norms of purpose, norms for maintaining/reproducing identity, norms of interaction (authority relations, cooperation, rules of fairness, norms of production/performance (for instance, having fun, producing new scientific or policy knowledge, or norms for doing business and making money and also satisfying clients)). There are also norms for accounting as well as for producing group narratives; norms about appropriate places and times for group activities. Game and interaction outputs—production of patterns are often normative equilibria.

- (3)

- A group or organizational rule configuration coordinates actors, contributes to organizing and regulating them; it enables participants to understand what is going on, who does what (or can do what), how, why, etc. It can be used thus to simulate and to predict (as long as the rule regime continues to be applicable and to function properly); also, the regime provides a basis for the asking and giving of group and individual accounts, to criticize and penalize wayward performance and outcomes as well as to praise and reward successful group and individual behavior.

- (4)

- A particular group rule configuration = group subculture = distinct rule regime or norm complex. A configuration has a “cultural logic” or rationality based on the regime organizing and regulating group and individual activities and outputs/outcomes. It contributes to defining a group and differentiating it from other kinds of groups. It contributes to defining types of group interaction situations and their “rules of the game”.

- (5)

- All functioning groups have identity rules—at least for referring to and reflecting on group conditions and behavior. For some groups, identity—especially identity contrasted with other competing or conflicting groups—is a major group dimension. While in some groups identity rules and identity are major factors in group life, in many other groups, identity is only a name or symbol for themselves, with no special value attached to the identity, other than their attachments to the group and/or its members.

- (6)

- Norms of cooperation and integration are found to varying degrees in all of the groups in Table 3 (and are typical of most ongoing groups, until conflict or death and disease undermine groupness). The obvious exception in our sample of groups is the “prison social organization” where there are barriers and norms of limited cooperation; there is often even relatively intense enmity between prison guards and prisoners. Cooperation among most members of terrorist groups tend to be highly constrained since cells are meant to be kept secret from the outside world and from one another (as part of their overall clandestine functions).

- (7)

- All groups have to acquire and maintain their material and agential bases (their place(s), particular technologies for group existence, recruitment of new members for purposes of replacement and/or growth, and some level of financing and resource support) Some groups are high-resource consumers (energy, water, land, or financial resources); others require minimal resources for their purposes and activities. This relates, of course, to issues of group vulnerability and sustainability.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Illustrations of Rules in Rule Categories

Appendix A.1. (I). Group Identity Rules

Appendix A.2. (II). Membership and Participation/Involvement Rules

Appendix A.3. (III). Shared Value Orientations and Ideals

Appendix A.4. (IV). Shared Beliefs and Models of Reality

Appendix A.5. (V). Social Structural and Relational Rules (Internal Governance)

- (a)

- What determines the “strength” of the group’s social structure—and integration—is the rule regime, group commitment to it, and group control over power resources (in part constituted and regulated by the regime) with which a group social order can be maintained, realized, and reproduced.

- (b)

- What is the appropriate basis of group members to orient to, adhere to, and comply with the rule regime? Above, we identified multiple (often over-determined factors in members’ commitment and compliance, although there is variation among members to a greater or lesser extent (Burns 2008)).

- (c)

- Integration of a group may occur because of external threat or challenge which members feel requires cooperation/collaboration to resist or overcome.

- (d)

- When members, particularly key members, lose their orientation and commitment to the group, the group is destabilized and is likely to erode or disintegrate, unless a revitalization is set in motion.

- (e)

- It is not only motivation and adherence which is critical to group order. Group functioning and stability depend on effective coordination, leadership, and conflict resolution as well as maintenance of group agential and resource bases. A group leadership may manage to synthesize or integrate a group as part of its leadership or governance functions.

- (f)

- Any group may, in general, consist of some degree, even extreme degrees, of weak ties. This is apparent in the case of groups built up on the basis of coercion or employment based on low remuneration and exploitation. Some elements of groupedness (compared to ideal type solidary or strong-tie groups) are missing or undefined.

- In general, in many groups, member commitment to the group, its norms, and its leadership are weak. Indeed, there may be no clarity about who is “controllable” and who is not, who is a genuine member and who is not. Weak-tie groups have weak controls over members, and members have relatively weak controls over one another and over the group as a whole. This makes for feeble and uncertain collective action, mobilization of resources, and effective social control.

- When people from a work place get together for a drink after work, they make up a group of sorts, but the ties are typically weak. Their purpose is none other than socializing. There are weak shared norms and possibly vague role differentiation, but not necessarily friendships or close affinities. Similar observations apply to variation in the degree-of-strength in dyads, triads, etc.

Appendix A.6. (VI). Rules for the Interface with the Environment (“External Governance”)

- (a)

- Boundary maintenance, a key group function, is produced through the effective application of recruitment and involvement rules and through particular strategies of procuring materials and technologies and interacting with the environment.

- (b)

- Groups function in networks and larger organizations as nodes in clusters (Fine 2010). Moreover, these are segments of networks in which weak ties (secondary ties) may be replaced with a set of strong (and intimate) ties (primary). Not all functioning small groups can be characterized by primary ties, as indicated elsewhere in this article.

- (c)

- Powerful groups develop rules and strategies for controlling the environment so as to make it compatible and supportive, enabling group sustainability and evolution. Indeed, given sufficient power, the group changes the environment so “it fits,” or “responds to its needs” (Burns and Hall 2012). The possession of such powers, of course, differs greatly among groups.

Appendix A.7. (VII). Production Rules and Procedures

- (a)

- Group members translate rule regimes and their rule categories—whose contents vary greatly among groups—into particular interaction patterns, social control and regulation, including the maintenance of role patterns, leadership, and group performances and outputs.

- (b)

- Social control including socialization is based on group specific agential and group procedural mechanisms: forms of recruitment, expulsion, and regulation of role performances (for instance, males and females, leaders and subordinates).

- (c)

- Patterns of agential powering vary among groups. Traditional (conventional) versus formal-legal patterns (in case of registered and publicly legitimized group, e.g., a condominium’s self-governance).

- (d)

- There are greater or lesser possibilities for any group member to exercise mutual influence depending on group norms and the rule regime generally.

Appendix A.8. (VIII). Rules and Procedures for Changing Rule Regimes and Group Conditions and Mechanisms

- For example, groups form for the purpose of transforming their status (ethnic or other status enhancement)

- Clubs, gangs, cliques, or other voluntary organizations often have the dual function of providing identity as well as status to members. For example, wearing certain clothes, hats, shoes, hajib, tattoos; eating or not eating certain foods and beverages; participating in certain rituals and ceremonies; rejecting association (particularly ritualistic occasions) with members of other groups (again, boundary maintenance)

- (a)

- There are internal value and governance mechanisms: in dynamic groups stressing learning, competition, the value of experimentation and innovation, on the one hand, versus those in static groups stressing stability and reproduction, adherence to routines and rituals, and minimization of internal and external competition and conflict.

- (b)

- External processes may produce in most groups’ pressures, threats, hazardous events, shocks evoking under some conditions efforts at adaptation and innovation among most groups. The pressures may come, for instance, from natural catastrophes or from the actions or growing threats from established powerful agents or new powerful agents emerging in a group’s context.

Appendix A.9. (IX). Technology and Resource Rules.

- Some groups may obtain the resources they require on the basis of property rights or political authority over resources, i.e., rules of access to and use of critical group resources. Other sources of power including normative and coercive capabilities may play a critical role.

- To obtain resources in the environment, groups typically have to deal with agents possessing or controlling access to some of these resources. These activities often entail dealing with external challenges and threats. In general, a group develops external governance strategies and functions for these purposes.

- Collective resources belong to the group—possibly obtained from group members or simply belonging to the group or community (through legal ownership, tradition, exchange, coercion). There are group procedures for deciding how to deploy the resources, for instance, through collective direction (leadership), or collective decision-making, or application of group norms.

- The group itself and its members (or particular members) are themselves key resources—for themselves and their productions including dealing with external agents.

Appendix A.10. (X). Time and place rules

References

- Abell, Peter. 2000. Sociological theory and rational choice theory. The Blackwell Companion to Social Theory 2: 223–44. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, Tom, Tom R. Burns, and Philippe DeVille. 2014. The Shaping of Socio-Economic Systems: The Application of the Theory of Actor-System Dynamics. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, Peter, and William R. Scott. 1962. Formal Organizations: A Comparative Approach. San Francisco: Chandler Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Tom R. 1990. Models of Social and Market Exchange: Toward a Sociological Theory of Games and Human Interaction. In Structures of Power and Constraint: Essays in Honor of Peter M. Blau. Edited by Craig Calhoun, Michael W. Meyer and William R. Scott. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Tom R. 2008. Social Rule System Theory: An Overview. In Rule System Theory: Applications and Explorations. Edited by Helena Flam and Marcus Carson. Frankfurt, Oxford and New York: Peter Lang Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Tom R., and Philippe DeVille. 2007. Dynamic Systems Theory. In The Handbook of the 21st century Sociology. Edited by Clifton D. Bryant and Dennis L. Peck. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Tom R., and Helena Flam. 1987. The Shaping of Social Organizations: Social Rule System Theory and Its Applications. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Tom R., and Anna Gomolinska. 1998. Modelling Social Game Systems by Rule Complexes. In Rough Sets and Current Tends in Computing. Edited by Lech Polkowski and Andrzej Skowron. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Tom R., and Anna Gomolinska. 2000a. The Theory of Socially Embedded Games: The Mathematics of Social Relationships, Rule Complexes, and Action Modalities. Quality and Quantity: International Journal of Methodology 34: 379–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, Tom R., and Anna Gomolinska. 2000b. Socio-cognitive Mechanisms of Belief Change: Applications of Generalized Game Theory to Belief Revision, Social Fabrication, and Self-Fulfilling Prophesy. Cognitive Systems Research 2: 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, Tom R., and Peter Hall, eds. 2012. The Meta-Power Paradigm: Structuring Social Systems, Institutional Powers, and Global Contexts. Frankfurt, New York and Oxford: Peter Lang Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Tom R., and Ewa Roszkowska. 2001. Fuzzy Game Theory: The Perspective of the General Theory of Games on Nash and Normative Equilibria. In Rough-Neuro Approach: A Way to Computing with Words. Edited by Sankar K. Pal, Lech Polkowski and Andrzej Skowron. Berlin and London: Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Tom R., and Ewa Roszkowska. 2004. Fuzzy Games and Equilibria: The Perspective of the General Theory of Games. In Rough-Neural Computing: Techniques for Computing with Words. Edited by Sankar K. Pal, Lech Polkowski and Andrzej Skowron. Berlin and London: Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Tom R., and Ewa Roszkowska. 2005. Generalized Game Theory: Assumptions, Principles, and Elaborations Grounded in Social Theory. Studies in Logic, Grammar, and Rhetoric 8: 7–40. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Tom R., and Ewa Roszkowska. 2006. Economic and Social Equilibria: The Perspective of GGT. Optimum-Studia Ekonomiczne 3: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Tom R., and Ewa Roszkowska. 2007. Multi-Value Decision-Making and Games: The Perspective of Generalized Game Theory on Social and Psychological Complexity, Contradiction, and Equilibrium. In Festskrift for Milan Zeleny. Amsterdam: IOS Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Tom R., and Ewa Roszkowska. 2008. The Social Theory of Choice: From Simon and Kahneman-Tversky to GGT Modelling Of Socially Contextualized Decision Situations. Optimum-Studia Ekonomiczne 3: 3–44. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Tom R., Tom Baumgartner, and Philippe DeVille. 1985. Man, Decisions, Society. London and New York: Gordon and Breach. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Tom R., Anna Gomolinska, and Loren D. Meeker. 2001. The Theory of Socially Embedded Games: Applications and Extensions to Open and Closed Games. Quality and Quantity: International Journal of Methodology 35: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, Tom R., Jose Caldas, and Ewa Roszkowska. 2005. Generalized Game Theory’s Contribution to Multi-agent Modelling: Addressing Problems of Social Regulatiion, Social Order, and Effective Security. In Monitoring, Security and Rescue Techniques in Multiagent Systems. Edited by Barbara Dunin-Keplicz, Andrzej Jankowski, Andrzej Skowron and Marcin Szczuka. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Tom R., Ewa Roszkowska, and Nora Machado. 2014. Distributive Justice. Studies in Logic, Grammar, and Rhetoric 37: 11–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, Tom R., Ewa Roszkowska, Ugo Corte, and Nora Machado. 2017. Sociological Approaches to the Reformulation of Game Theory: Models, Comparisons, and Implications of a Social Science Game Theory. Optimum. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, Marcus, Tom R. Burns, and Dolores Gomez Calvo. 2009. Public Policy Paradgims: Theory and Practice of Paradigm Shifts in the European Union. Frankfurt, New York and Oxford: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Dermott, Terry. 2005. Perfect Soldiers: 9/11 Who They Were, Why They Did It. New York: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, Émile. 1976. The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. London: Allen and Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Edling, Christofer R. 2002. Mathematics in sociology. Annual Review of Sociology 28: 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzioni, Amitai. 1975. Comparative Analysis of Complex Organizations, rev. ed. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, Gary A. 2010. The Sociology of the Local: Action and its Publics. Sociological Theory 28: 355–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, Gary A. 2012. Tiny Publics: A Theory of Group Action and Culture. New York: Russell Sage Foundation Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Flam, Helena, and Marcus Carson. 2008. Rule Systems Theory: Applications and Explorations. Frankfurt, New York and Oxford: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, Anthony. 1984. The Constitution of Society. Oxford: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 1959. In the Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 1961. Encounters. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 1969. Strategic Interaction. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 1974. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gomolinska, Anna. 2002. Derivability of Rules from Rule Complexes. Logic and Logical Philosophy 10: 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomolinska, Anna. 2005. Towards rough applicability of rules. In Monitoring, Security, and Rescue Techniques in Multiagent Systems. Edited by Barbara Dunin-Kęplicz, Andrzej Jankowski, Andrzej Skowron and Marcin Szczuka. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 203–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gomolinska, Anna. 2008. Rough Rule-Following by Social Agents. In Rule Systems Theory: Applications and Explorations. Edited by Helena Flam and Marcus Carson. Frankfurt, New York and Oxford: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Gomolinska, Anna. 2010. Satisfiability judgement under incomplete information. Rough Sets XI: Journal Subline of Lecture Notes in Computer Science 5946: 66–91. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, Mark S. 1973. The Strength of Weak Ties. American Journal of Sociology 78: 1360–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, Mark S. 1985. Economic Action and Social Structure and the Problem of Embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology 91: 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, Neil. 2009. A Pragmatist Theory of Social Mechanisms. American Sociological Review 94: 358–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannerz, Ulf. 1992. Cultural Complexity: Distributive View of Culture. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harre, Rom. 1979. Social Being. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Harre, Rom, and Paul F. Secord. 1972. The Explanation of Social Behavior. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Karpik, Leon. 1981. Organizations, Institutions, and History. In Complex Organizations: Critical Perspectives. Edited by Mary Zey-Ferrel and Michael Aiken. Glenview: Scott, Foresman and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Kean, Thomas. 2014. Report of the U.S. National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the USA; Washington: Government Printing Office.

- Loia, Vicente, Guiseppe D’Aniello, Angelo Gaeta, and Francisco Orciuoli. 2016. Enforcing situation awareness with granular computing: A systematic overview and new perspectives. Granular Computing 1: 127–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotman, Jury. 1975. Theses on the Semiotic Study of Culture. Lisse: Peter de Ridder. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, Nora. 1998. Using the Bodies of the Dead: Legal, Ethical, and Organizations Dimensions of Organ Transplantation. London: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, Nora, and Tom R. Burns. 1998. Complex Social Organization: Multiple Organizing Modes, Structural Incongruence, and Mechanisms of Integration. Public Administration: An International Quarterly 76: 355–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirowski, Philip. 1981. Is There a Mathematical NeoinstitutionalEconomics? Journal of Economic Issues 15: 593–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirowski, Philip. 1986. The Reconstruction of Economic Theory. Boston and Dordrecht: Kluwer-Nijhoff. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, Talcott. 1951. The Social System. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Perrow, Charles. 1967. A Framework for the Comparative Analysis of Organizations. American Sociological Review 32: 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, Trond. 1994. On the Promise of Game Theory in Sociology. Contemporary Sociology 23: 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, Roland. 1989. Toward a Semiotic Explication of Anthropological Concepts. In The Nature of Culture: Proceedings of the International and Interdisciplinary Symposium, Bochum, October 7–ll, 1989. Edited by William A. Koch. Bochum: Studienverlag Dr. Norbert Brockmeyer. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, Woody W., and Paul J. DiMaggio, eds. 1991. The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roszkowska, Ewa, and Tom R. Burns. 2010. Fuzzy Bargaining Games: Conditions of Agreement, Satisfaction, and Equilibrium. Group Decision and Negotiation 19: 421–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmel, Georg. 1898. The Persistence of Social Groups. American Journal of Sociology 3: 662–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowron, Andrzej, Andrzej Jankowski, and Samuel Dutta. 2016. Interactive granular computing. Granular Computing 1: 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowron, Andrzejand, and Andrej Jankowski. 2016. Rough sets and interactive granular computing. Fundamenta Informaticae 147: 371–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedberg, Richard. 2001. Sociology and Game Theory: Contemporary and Historical Perspectives. Theory and Society 30: 301–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittrock, Bjorn. 1986. Social Knowledge and Public Policy: Eight Models of Interaction. In Social Science and Governmental Institutions. Edited by Charles Weiss and Henry Wollrnan. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Zelizer, Viviena. 2012. How I Became a Relational Economic Sociologist and What Does that Mean. Politics & Society 40: 145–74. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The main goal of the article is not, however, presentation of strict mathematical tools “for modeling behaviour of diverse groups” and technical formalization; rather, it provides the conceptual, methodological and descriptive foundations for such modelling. However, we have accomplished some technical formalization. One of our collaborators, Anna Gomolinska has developed “technical machinery” such as soft applicability of rules, as well granular computing (Gomolinska 2008, 2002). Gomolinska (2005) studied soft applicability of rules (including decision rules) within the framework of rough approximation spaces. Such a form of rule applicability, called rough applicability, is based on various kinds of rough satisfiability of sets of rule premises, where granulation of information plays an important role. Gomolinska (2010) has presented the rough granular view on the problem of satisfiability of formulas (defining some conditions) by objects under incomplete information about the objects and the situation. Judgement of formula satisfiability is important, e.g., when making the decision whether or not to apply a rule to an object. Data granulation and granular computing are some of the methods for modelling and processing imprecise and uncertain data. In general, granular computing can be viewed as: (i) a method of structured problem solving; (ii) a paradigm of information processing; and (iii) a way of structured thinking (Skowron and Jankowski 2016; Skowron et al. 2016; Loia et al. 2016). |

| 2 | In the social science literature a standard distinction is made between formal and informal rules. Formal rules are found in sacred books, legal codes, handbooks of rules and regulations, or in the design of organizations or technologies. Informal rules, in contrast, are generated and reproduced in ongoing interactions—they appear more spontaneous, although they may be underwritten by iron conduct codes. The extent to which the formal and informal rule systems diverge or contradict one another varies. Numerous organizational studies have revealed that official, formal rules are seldom those that operate in practice (Burns and Flam 1987). More often than not, the informal unwritten rules not only contradict formal rules but in many instances take precedence over them, governing organizational life. |

| 3 | Social rule systems play a key role on all levels of human interaction (Burns et al. 1985; Burns and Flam 1987; Burns and Hall 2012; Giddens 1984; Goffman 1961, 1974; Harre 1979; Harre and Secord 1972; Lotman 1975; Posner 1989; among others), producing potential constraints on action possibilities but also generating opportunities for social actors to behave in ways that would otherwise be impossible, for instance, to coordinate with others, to mobilize and to gain systematic access to strategic resources, to command and allocate substantial human and physical resources, and to solve complex social problems by organizing collective actions. |

| 4 | |

| 5 | There are not only role grammars but semantics and pragmatics, hence processes of meaning, interpretation, and adaptation associated with rule application and implementation. |

| 6 | Zelizer (2012) points out the importance of account-giving (as part of any established relationship); she refers to how people “repair” relations by justifying or explaining their actions which have caused damage or problems: “someone tells a story to show that the damage was inadvertent or unavoidable—“accidental”—and, therefore, despite appearances, does not reflect badly on the relationship between the actors. “Why” or “what were you thinking”. |

| 7 | The determination of the universal rule categories for groups, diverse social organizations, and institutions was based on: (1) language categories that are reflected in “questions” and definitions/descriptions of socially regulated interaction situations: who, what, for what, how, where, when (Burns et al. 1985; Burns and Flam 1987); (2) interaction descriptions and analysis (of contextualized games, C-games) (Burns and Gomolinska 2000a; Burns and Roszkowska 2005, 2007, 2008); (3) comparative institutional analysis (Burns and Flam 1987). |

| 8 | The focus here is on relational and organizational grammars. There are other types of social grammars such as those of language and money (Burns and DeVille 2007). |

| 9 | Although the focus of the research is on modern social organizations, the theory is applicable to families, clans, communities, etc. The theoretical and empirical research clearly demonstrated that there is no scale problem. |

| 10 | In the sociological game theory work of Burns and Gomolinska (2000a, 2000b), Burns, Gomolinska, and Meeker (Burns et al. 2001), and Burns and Roszkowska (2005, 2007, 2008), games and established interaction settings are characterized and distinguished in terms of their particular grammars—grammars which allow one to predict the interaction patterns and equilibria of interaction settings and games. |

| 11 | Rules and rule regimes need not be explicit buy may be tacit, or partially tacit. At the same time, group members and outsiders may have misconceptions about the rules and their application. Thus, group members may deceive themselves and others about what rules they are applying and what they mean in practice, deception may be institutionalized in the form of ready-made discourses defining or explain a regime as just or efficient or optimal—for example, a market regime—when it is not. Members as well as outsiders may see what they have been led to see and understand. |

| 12 | In Appendix A, we present in more detail these universal rule types/categories (10) that make up a group or organizational rule regime. |

| 13 | This is not some “laundry list”, hence our emphasis on the structure or architecture of rule regimes (Carson et al. 2009). The specification and analysis of rule complexes making up architectures goes back almost 40 years and was the basis of a reconceptualization of the theory of games and human interaction, a sociological theory of games (Burns 1990; Baumgartner et al. 2014; Burns and Gomolinska 2000a; Burns et al. 2001), and Burns and Roszkowska (2005, 2007, 2008; among other articles). |

| 14 | A rule regime does not necessarily consist of formal, explicit rules. It may be an implicit regime, which members of a group do not reflect upon (unless or until there is a crisis or performance failings, a “failed group experience”). The degrees of completeness as well as institutionalization of the regime are variables (see Footnote 4). |

| 15 | Shifts in the rules of public policy paradigms governing areas of policy and regulation are investigated and identified in Carson et al. (2009); the shifts concern values and goals, agents considered responsible, expertise, appropriate means, among other key rule changes. |

| 16 | SGT involves the extension and generalization of classical game theory through the formulation of the mathematical theory of rules and rule systems and a systematic grounding in contemporary social sciences (the classical theory is a special case of the more general SGT) (Burns et al. 2001, 2005, 2017; Burns and Gomolinska 1998, 2000a, 2000b; Burns and Roszkowska 2005, 2006, 2007). Sociological concepts such as norm, value, belief, role, social relationship, and institution as well as classical game theory concepts can be defined in a uniform way in SGT in terms of rules, rule complexes, and rule systems (which in formalized SGT are also defined as mathematically objects). These tools enable one to model social interaction taking into account economic, social psychological, and cultural aspects as well as considering games with incomplete, imprecise or even false information. This approach has been developed by Tom Baumgartner, Walter Buckley, Tom R. Burns, Philippe DeVille, Anna Gomolinska, David Meeker, and Ewa Roszkowska, among others. |

| 17 | SGT, in addition to its empirical grounding, provides the conceptual and mathematical foundations of rules and rule systems (Burns and Gomolinska 2000a; Burns and Roszkowska 2005, 2007)—ironically, classical theory defined games as systems of rules but never developed a conceptualization and mathematics of rules and rule systems. |

| 18 | Open games—with their opportunities for creativity and innovation—are obviously less predictable in their interaction and outcome patterns than closed games with fixed action repertoires and given outcomes. Even in many closed games the actors vary to a greater or lesser extent in their interpretations, adjustments, and enactments of the norms and algorithms associated with their roles, introducing variation in the situation (for instance, in superordinate-subordinate interactions, in peer group interactions, or in gender interactions). |

| 19 | SGT readily incorporates the possibilities of “communication among players” and the making of binding agreements—which are the bases of what are referred to in classical game theory as “cooperative games”. But there is much greater variety and complexity in human interaction—in particular, communication—than the distinction between cooperative and non-cooperative games would suggest. |

| 20 | Emotional judgment algorithms result in particular actions in “emotionally charged situations”. Expressive or communication action entails enacting a script in a defined or appropriate situation. |

| 21 | At the same time, ASD’s theory of social action and interaction rejects the conception of an abstract, super-rational actor underlying rational choice, economics and game theories. Or more precisely, it treats games be-ween “rational egoists” as only a special, limiting case. ASD assumes, instead, that human agency—choice, action and interaction—are socially embedded (Granovetter 1985). The focus is on socially constituted agents, their roles, role relationships, cultural and institutional frames that orient and constrain them in their interactions. The theory identifies the organizing principles, social relationships and rules that actors apply to specified interaction situations and that make for particular action and “interaction logics” (Karpik 1981; Wittrock 1986) or socially conditioned rationalities (Burns and Flam 1987). In other words, rationality is a function of the rules, rather than rules being a simple expression of rationality (see Mirowski 1986; 1981, p. 604). |

| 22 | There are many institutionalized forms of cooperation: from classical game theory ‘minimalist’ forms where the actors can communicate and make binding agreements to cooperative forms entailing sharing group identity, powerful solidarity, and compelling normative framework defining correct (and, of course, incorrect) relations of cooperation. |

| 23 | As in the case of cooperative and collaborative relations, there are multiple forms of “conflict” relations: from classical game theory’s “zero-sum” interaction situation (defined in terms of payoff structure) to relationships with mixed orientation among the actors (positive and negative feelings) as well as to relationships strong emotional hostility, even hatred. |

| 24 | Zelizer (2012) (and also C. Tilly) refer to this type of phenomenon in terms of creating, maintaining, transforming, or terminating (interpersonal) relations. Zelizer identifies four kinds of such relational or meta-power work: (A) creation of new relations; (B) maintaining existing relations (among other things, “affirming” existing relations); (C) negotiating shared definitions of relations (including situational definitions); (D) correcting or regulating immediate deviations; (E) repairing damaged relations; (F) restructuring or transforming relations. |

| 25 | Social rule system theory (Burns 2008; Burns et al. 1985, Burns and Flam 1987; Flam and Carson 2008) was formulated and developed in the 1980s making a modest contribution to the new institutionalism (Powell and DiMaggio 1991). |

| 26 | In contrast, rational choice and game theories provide little or no analytical capability to address such matters, in large part because they lack conceptual tools to deal with such universal matters as social values, norms, social structures, institutional and cultural formations, value dilemmas and conflicts. The utilitarian foundation is simply all too constraining. |

| 27 | Some like Peterson (1994), but also Swedberg (2001), claim that Game Theory has proved only sporadically useful to sociologists, while Abell (2000) argues it ought to have a greater influence in sociology, and Edling (2002) claims that it has mostly affected mathematical sociology, but that its core—yet most basic principle “…that social actors interact, and are affected by game outcomes, albeit in different ways, by that interaction” is basic sociology. While Swedberg (2001) long ago pondered the possibility of developing a distinctively sociological game theory approach without acknowledging earlier initiatives such as IGT and SGT, he mostly saw and partially articulated the idea of game theory in order to theorize “counterfactuals”. But, of course, given its empirical failings, it would be a poor tool for generating ‘counterfactuals’. |

| 28 | Concerning gender, women use makeup, utilize “sexy” or “feminine” clothes (especially, lipstick and other face makeup, bras, high-heel shoes, dresses) to express or to emphasize their identity. At the same time that they are constructing their female identities, men may misinterpret this behavior as an ‘invitation’, a “come-on”, revealing a “readiness for sex”. It is not surprising that young girls may hardly understand the full meaning of what they are doing as they try to become “women”. |

| 29 | Examples of complex games comes from Ugo Corte’s ethnographic work on the social world of surfing and big wave surfing in particular. Surfers’ scarce resources are waves. Surfers compete with one another, and also collaborate, to catch as many of the best waves during a specific day without letting any major waves go by un-ridden and thus wasted. Surfing is a subtle and complex social game—with strategic as well as rule following and ritual behavior—in a natural context of waves to be used in performance, but in some instances entailing danger and risk part of it derived from the activity itself, while the rest having to do with the releant complex of social norms. |

| 30 | The methodological approach linking universal rule categories to the particular rule contents in these categories may have parallel’s with Simmel’s formalism where universal grammars with respect to which actors behave in ways characterized by the particularity of their contexts (Gross 2009). |

| 31 | The linkages may vary in the tightness (or looseness) of their couplings. In a loosely coupled configuration, a disturbance or shift in the rules of one category may not readily spread to the rules of other categories. On the other hand, in a tightly coupled configuration, a disturbance in the rules of one category tend to destabilize others. |

| 32 | The purposes are “legitimate” ones—and ideal types at that. But military as well as police purposes may be transformed (or degenerate) into counter-opposition and political repressive missions instead of “national defense” and ordinary “law enforcement functions”, respectively, substantially poisoning the institutions and impacting negatively on their societies, processes exemplified in many contemporary Latin American and African countries. |

| 33 | Interestingly, Charles Perrow (1967) suggested a similar idea for the comparative analysis of organization, although he claimed to reject “systems theoretic” approaches (personal communication). He framed his model in terms of patterns of variables rather than patterns of rules. Of course, rule patterns are translated or implemented in patterns of performances/outputs and practices, therefore, readily expressable in terms of variables. His intuition was that an ideal type of organization would have particular properties making up a configuration. And he rightfully suggested that this basis for comparative analysis and distinctions among types was more powerful than the typologies proposed by Talcott Parsons (functionalism) (Parsons 1951), Amitai Etzioni (the bases of organizational control) (Etzioni 1975), Peter Blau and Richard Scott (the dimension of who benefits or gains from organizations) (Blau and Scott 1962), etc. |

| 34 | As suggested earlier, any given configuration will have a history and evolutionary dynamic driven and shaped by internal as well as external forces. |

| 35 | In other words, in SGT perspective, the abstract group is an ideal type. Any empirical case can be located in a space between the ideal type and its counterpoints in practice, where distances are measured on multiple dimensions, although the notion of a “group” is a fuzzy concept—any empirical group is an approximation to an ideal type group. It can usually be distinctly differentiated from its negation or opposite, a collection of non-related actors neither oriented nor committed to any social organizational regime regulating members’ behavior and group behavior as a whole. |

| 36 | Another rule configuration property would be the degree of coupling (tight vs. loose coupling) among rules: the extent to which the activation of one rule or rule complex/algorithm leads to the automatic activation of one or more connected rules or rule complexes/algorithms (articulated in the work of Charles Perrow (1967)). Some rules have buffers between them, or agents making judgments whether or not to pass a signal on—such “loose coupling” may or may not occur through the intervention of human agents or may occur through design of the system. Perrow and others have used considerations such as “tight coupling” to assess the degree of vulnerability of financial systems or other socio-technical systems to go out of control and crash. Consideration of degree of tight coupling and degree of coherence leads to an insightful 2 × 2 table (other properties of rule systems may be taken into account and introduced into such analyses). |

| 37 | This conception of coherence can be related to what the neo-institutionalists refer to—mostly metaphorically—as “institutional logic” (or logics). |

| 38 | Notice that the need to coordinate participants and maintain social order is arguably a more decisive factor in general than technology in determining group social organization (cf. Perrow 1967). |

| 39 | The purposes are “legitimate” ones—and ideal types at that. But military as well as police purposes may be transformed (or degenerate) into counter-opposition and political repressive missions instead of “national defense” and ordinary law enforcement functions, respectively, substantially poisoning the institutions and impacting negatively on their societies, processes exemplified in many contemporary Latin American and African countries. |

| 40 | In most group contexts “fit” or “appropriate” are fuzzy concepts rather than precise or “crisp”. |

| 41 | What we are doing here may relate to Merton’s juxtaposition of values and norms (means) in his famous table of deviance. Of course, he overlooked technologies, time, place, social structure, etc. in his highly abstract characterization. |

| 42 | Groups do not establish rule configurations from scratch. They typically make use of “cultural blueprints or algorithms” for setting up a particular group. Of course, the group makes adjustments and adaptations based on the people involved, the context, etc. at the same time there are “family resemblances among the patterns of a certain ideal type of group”. |

| 43 | Of course, there are odd units that do not fit this pattern very neatly, for instance, “military intelligence”, “drone units”, “purely administrative staff”, etc.—and provide some of the humor as well as challenges to “fit them in” appropriately (see below on multiple logics in groups and organizations). |

| 44 | The stress here is on rule configurations that make sense, and in that respect are considered coherent. But group members typically consider it important for themselves and others that their identity is coherent. They use particular discourses for this purpose. They also make distinctions in their accounts between front-stage and back-stage performances and discourses in order to convey a coherent identity, not one that is fragmented, inappropriate, contradictory, etc. The front-stage and back-stage variants are usually incoherent to a greater or lesser extent. |

| 45 | The larger cultural-institutional context may support, for instance, equality, democracy, or secularity, but the group regime is oriented to inequality, extreme authoritarianism, or religious fanaticism, even vicious criminal behavior (or, vice versa, when a democratic group like the Brazilian football team, the Corinthians, after an internal democratization process, decides in the early 1980s to launch a national-wide process that contributed to establishing democracy in Brazil. This became an effective and powerful movement, given the significance of football in Brazil and the national prestige of several of the Corinthians players). Group incoherencies generate the development of front stage-back stage differentiation (see later discussion) but, in some cases, motivates movements to overcome incoherence as in the case of the Corinthians movement in Brazil, striking out at societal tyranny and anti-democratic practices. |

| 46 | Illustrations are numerous and diverse: The U.S. Supreme Courts upheld a criminal ban on the use of peyote in Native American sacramental practices. On the other hand, peyote-using groups may maintain a front stage compliance with the law and a backstage violation of the law under conditions where concealment is possible (see later discussion of frontstage and backstage differentiation). |

| 47 | The purpose of an ethnically oriented group might be similar to the social group in column B of Table 3, namely to get together to enjoy themselves playing ethnic games, ethnic dancing and singing. But its purpose might also be (or become (under conditions of threat)) to protect or advance the ethnic group (a transition would occur between a purely social group for self-enjoyment and a more militant and outwardly aggressive type group). In the latter case, this may require arming itself, possibly obtaining resources of weapons through criminal means. In this way, they become a multi-logic group. In addition to the logic of an inwardly oriented ethnic group, it develops the logic of an armed group to carry out violence against others as well as to engage in the pursuit of income and other resources through criminal means. These pursuits put them, of course, at odds with the larger society—at the same time their militancy may escalate in response to policing and “repression” from the larger society. |

| 48 | There are almost daily revelations about individual and collective agents deviating from legal and normative requirements: In politics, one observes political parties’ “dirty tricks”, “Watergate” rigged elections; in the corporate world: Enron’s bookkeeping fraud, Bernard Madoff’s ponzi scheme, Cendant corporation scandal, Bernard Ebbers’ WorldCom securities fraud, etc.; Health care: the French blood scandal (HIV contaminated blood), illegal buying and selling of organs for transplantation; cases of euthanasia and mass murders in hospitals; scandals of NGOs, universities, and research institutes in the illegal or improper use of their funds; public and private organizations: release of toxic chemicals, dumping of hazardous wastes, including Love Canal Disaster and innumerable other tragedies, etc. |

| 49 | Corruption can be treated in this way if there are legal/administrative requisites concerning proper group behaviour. One can speak then of incoherence. But a group configuration might be designed in such a way that some would consider it “corrupt”, but the group itself considers the configuration fully appropriate and not discrepant with respect to its own norms, laws, etc. Even in the case there are laws and regulations against some forms of corruption, group members may believe and argue that no one is adhering to the laws and regulations, therefore they are defunct, and thus there is no incoherence between the legal requisites and their own practices. Corruption is the norm in this case. |

| 50 | The confidence game entails a ploy confidence people use for obtaining money from one or more persons under false pretences (the exercise of deceit). A “con-person” builds up informal social relationships with roles constructed for the purpose of abusing them; such exploitation is practiced in banks and business organizations by persons who have learned to abuse positions of trust. There are increasing numbers and examples of “conning” through internet presentations of self (Goffman 1959). Goffman (1959, pp. 218–19) points out: we find that confidence men must employ elaborate and meticulous personal fronts and often engineer meticulous social settings, not so much because they lie for a living but because, in order to get away with a lie of that dimension, one must deal with persons who have been and are going to be strangers, and one has to terminate the dealings as quickly as possible. |

| 51 | The distinction is found in the differentiation between “battle-ready units” and “barracks units”. |

| 52 | Of course, the context is important. A business unit in a demanding regulative environment or in a highly competitive environment may be subject to stringency and coherency controls differing significantly from a unit in a far less demanding environment (see later comment on stable and unstable environments). |

| 53 | Although a research unit is highly task-oriented and concerned with performance, there may be no overall coordination and regulation, unless it entails a mega-project like the Manhattan Project. There may be, therefore, multiple purposes, diversity in methods and means. |

| 54 | Notice that the need to coordinate participants and maintain social order is arguably a more decisive factor in general than technology in determining group social organization (Perrow 1967) (see footnote 34). |

| 55 | In times of change, adaptation of some rules or replacement/new selection may be considered necessary, but some changes are typically prioritized over others—in an appropriate or coherent manner. |

| 56 | On the other hand, if the purpose of a given group is to “test” or “find uses for” a particular technology, this would provide the foundation or decisive principle for the group’s institutional logic. Perrow (1967) claims a general, decisive role for technology. In our perspective, the rules of group purpose, leadership, and production function are usually more decisive, indeed often determining the criteria for specifying or selecting the technology and other resources. At the same time, once the latter are specified, they play a role in further rule determinations or selections, for instance, where the selection of the place(s) that group operations may be located and the times they may operate. Thus, contrary to Perrow, technology is not consistently a determining factor, although nevertheless an important structuring factor). Notice that the social activity group (column 3 in Table 2) may have decided to get together to bowl or to play pool. Once this choice (the activity and technology) has been decided, however, other determinations follow: where they would getting together, the times for doing this. Therefore, other constraints and constrictions come into play, although the main purpose of the group is simply to get together for sociability and fun. |

| 57 | Incoherent group functioning. A highly incoherent group where many of the rules of the group configuration do not fit one another readily—or do not fit the conditions/context of the group, result in decline in capabilities and performance failings. We are so accustomed to some minimum level of coherence, that we can hardly imagine the truly incoherent. But writers and performers do so, for instance Dostoevsky (Crime and Punishment), Kafka (The Process, etc.), the Marx Brothers (they could make their thousands of jokes because of our common understandings of coherence or order—even how particular types of groups should function); the director Tarantino played on this in Pulp Fiction. |

| 58 | What can be shown is the problematic nature of incoherence and incompatibilities in rule configurations. Particularly problematic is incompatibility of configurations with respect to group size, technologies, the knowledge and capabilities of group members, group tensions and conflicts, tensions and conflicts with external regimes and/or agents. The result is that members cannot properly or effectively perform norms, roles, production algorithms cannot be properly or effectively performed; there are group and individual performance failures. As a result, pressures and initiatives tend to arise within groups to increase the levels of compatibility—these may or may not lead to improvement. |

| 59 | Size and scale are long-recognized factors in social science and sociology. For instance, as a group grows in size, it often will develop at more or less the same time (or, possibly, with a time-lag) appropriate rules and procedures for production functions, internal governance processes, collective decision procedures, etc. |

| 60 | Some ethnic, religious, professional, and other groups are consistently dressed for public presentation of identity: many Islamic groups, nuns, priests, monks, military, police, etc. |

| Rule Types | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Type I | Identity rules—“Who are we?” “What symbolizes or defines us?” |

| Type II | Membership, Involvement, and Recruitment Rules—“Who belongs, who doesn’t?” “What characterizes members?” “How are they recruited?” |

| Type III | Rules concerning shared value orientations and ideals—“What does the group consider good and bad?” |

| Type IV | Rules concerning shared beliefs and models—“What do we know and believe about ourselves, our group behavior, and our environment”. |

| Type V | Social relational, group structuring, and governance rules. “How do we relate to one another, what is our social structure?” “What are the authority and status differences characterizing the group?” “How do we interact and reciprocate with one another and with the leadership?” “What are the rules of internal governance and regulation?” |

| Type VI | Rules for dealing with environmental factors and agents (“external governance”). “How do we cope with, make gains in the environment, dominate, or avoid environment threats?” |

| Type VII | Group production and activity rules. “What are our characteristic activities, practices, production programs, ceremonies and rituals?” “How do we coordinate activities and make collective decisions?” |

| Type VIII | Rules and procedures for changing the rule regime, or for changing core group conditions and mechanisms. “How do we (or should we) go about changing group structures and processes, our goals, or our practices?” |

| Type IX | Technology and resource rules. “What are appropriate technologies and materials we should use in our activities (and possibly those that are excluded)?” |

| Type X | Time and Place Rules—“What are our appropriate places and times?” |

| Rule Type | Terrorist Group Rule Configuration (For instance, the 9/11 Group; see Dermott 2005; Kean 2014; also Table 3) |

|---|---|

| Defining Identity (I) | Group name, possibly logo. Identity associated with the terrorist goals and possibly with the particular methods or strategies used. “Negative” dress code to conceal identity when operating clandestinely. |

| Recruitment of Membership Participation/Involvement (II) | Recruitment and training of capable and committed members, willing and able to carry out terror acts. Covert participation. Dress code and code of silence to conceal identity. Strict obedience to leaders and group rules. |

| Shared Value(s), Purposes, Goals (III)32 | Orientation to carry out deadly attacks against designated categories of targets; accomplish destabilizing actions, create terror. |

| Shared beliefs/Model of reality rules (IV) | The world is divided between Muslim believers and non-Muslim believers; the latter are enemies, polluters that will undermine and destroy Islam. Even some “quasi” Muslim groups are a threat to a holy Islam. |

| Group Relations of Reciprocity and Leadership (V) | Strict hierarchy, maintenance of strict separation among members (thus, independent cells). |

| Production and Output Functions (group protection and maintenance; hostile and destructive actions) (VI) | Deployment and use of terrorist weapons; actions to conceal identity and operations. Procurement of weapons, safe houses, financing; Appealing to potential recruits. |

| Relations with the Environment (VII) | Identification of enemies and targets; concealment, avoiding detection and monitoring. Identification of potential recruits. |

| Rules and Procedures for Changing the Rule Regime, Particular Rules | Ways the group changes rules, roles, and policies. Typically, part of an authoritative hierarchy. |

| Group Resources (IX) (materials and technologies) | Weapons of destruction; safe houses. Sufficient funding to obtain weapons and establish effective concealment; and to engage in the preparations such as training and travel. |

| Times and Places for Group Activities (X) | 24-7 readiness, available safe group spaces, training camps. |

| Business Unit (A) (Illustration) | R&D Institute (B) (Illustration) | Recreational, e.g., a Club (C) (Illustration) | Professional Army Unit (D) (Illustration) | Terrorist Group (Illustration) (E) | Prison Institution (F) (Illustration) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Defining Identity (I) | Trade name, logo; possibly badges, dress code, even uniforms. Likely a particular location or building(s). Identity also defined by the goal orientation to economic gain (which often trumps other goals) (see category III) | Institute name, possibly logo. Minimal or no dress code. Identity associated with the research goals, typically in a particular research area and possibly with the methods or equipment used. | Group name (e.g., club name), possibly with logo. Minimal or no dress code. Identity associated in part with the particular group activity and its location. | Unit's name, logo or insignia and markings of rank. Particular military uniform as dress code. Possibly a particular location. Identity in part defined by the goal orientation and the means used (military power) (see rule categories (III) and (VI)) | Group name, possibly logo. Identity associated with the terrorist ideology and goals and possibly with the particular methods or strategies used. “Negative” dress code to conceal identity | Prison name. Guards also uniformed. Identity associated with the purposes, means, technologies, characteristics of the prison and its population. Prisoners typically subject to a uniform dress code. Thus, dual social order |

| Recruitment (II) | Skill-based recruitment; Search for persons and groups sufficiently oriented to and acceptant of remuneration levels provided as well as performance demands | Recruitment based on expertise/merit, and/or formal education/training of individuals or groups in the relevant field or domain of the group. | Affinity group of friends, relatives or people with common interest in the recreation (“buffs”) and getting together. | Formal recruitment and training of able and willing unit members to obey and perform violent acts (based on honor, payment (mercenaries), conscription (coerced involvement)) | Recruitment and training of capable and committed members, willing and able to carry out terror acts | Guards are recruited. Strictly speaking, prisoners are not “recruited”. They have been arrested and confined. Thus, again a dual social order. |

| Membership and Participation/Involvement (II) | Contractual engagement. Members are remunerated and with careers and rewards for high performance. Sanctioning for disloyalty and disobedience. | Members are remunerated and with careers. Informal, relatively lax sanctioning for breaking group norms and values. Loyalty to the knowledge production cause and the professional code of ethics—negative sanctioning for deviance from these. | Informal, relatively lax sanctioning for breaking group norms and values. However, there are limits. | Members are typically remunerated and with careers in modern armies. Highly codified, harsh punishment for breaking key group rules, in particular those concerning loyalty and obedience to the leadership, group norms, and its symbols | Covert participation. Dress code and code of silence to conceal identity. Strict obedience and loyalty to leaders, group rules, and symbols. | Dual social order. Guards are remunerated and with careers—and are expected to obey rules and exhibit loyalty to the prison administration. Prisoners are alienated and generally oppositional. |

| Purposes/Values (III)39 | Pursuit of money-making; possibly also values of making quality goods and services, satisfying clients | Produce new knowledge or technology. Innovate/create and experience “flow”, possibly also to achieve symbolic power and scientific prestige as well as “gains in resources”. | Mutual pleasure, getting together, “having fun” | Defense/ Offense (external); also, orientation to possibly exercising control internal to the society (coups) | Orientation to carry out deadly or intimidating attacks against designated categories of targets; create terror, accomplish destabilizing actions. | Maintain law and order. Divided (and divisive purposes) between guards and prisoners. |

| Group Relations of Governance, Leadership and Reciprocity (V) | Hierarchical social order. Supervisor planning and monitoring of production activities; regulating and sanctioning inappropriate deviance | Professional forms of governance and regulation. Likely status differences and symbolic hierarchical order. Exchange, reciprocity, and competition more generally. | Minimal formality and hierarchy but possibly with status differences. Usually amicable negotiations and agreements among members. Someone or some members expected to plan and coordinate meetings | Strict hierarchy and stringent monitoring and sanctioning of behavor. Possibly high reciprocity and support among members | Strict hierarchy, maintenance of sharp separation among units (individuals and subgroups) | Prison leadership and guards make up an administrative system. Prisoners form informal groups for recreation, illegal activity |

| Production Functions and Outputs (VI) | Gaining necessary materials and technologies. Performing production and commercial activities. Achievement of economic gain from production and commercial activities | Gaining necessary materials and technologies. Performing research. Initiate and accomplish potentially innovative or creative projects along with publishing and gaining scientific recognition and status. | Gaining access to activity space, materials, and technologies for group activities. For instance, engagement in particular sport activities (amateur) | Gaining access to territory, technologies, and other materials as well as financing. Deployment and exercise of armed force or its threat, for instance in territorial defense or offensive action. | Procurement of weapons, funding, and access to safe houses. Deployment and use of terrorist weapons; action to conceal identity and operations. | Prison administration has prison routines and technologies (including weapons) to control prisoners. Prisoners typically try to engage in various illegal or forbidden activities |

| Relations with the Environment (VII) | Rules and strategies for dealing with financers, suppliers, competitors, and regulators Oriented dynamically to goods and services markets. | Rules and strategies for dealing with funders, suppliers, competitors, regulators, and the professional community. Strategies vis-à-vis funders, competitors, relevant professional communities | Loose boundaries. But rules and strategies for dealing with suppliers and regulators as well as others in the environment | Strategies for obtaining essential materials, technologies and financing. Dealing with funders, suppliers, and regulators Dealing with external enemies or threats. Maintaining strict boundaries. | Dealing with funders and suppliers as well as with monitors and potential observers. Identification of enemies and targets as well as threats; concealment, avoiding detection and monitoring | Prison administration deals with funders, suppliers, and regulators Prison tries to strictly control prisoner exchanges with the environment. |

| Rules and Procedures for making or Changing Rules (VIII) | Dual system. Group management or higher management engages in meta-powering and rule changing | Flexible, individual choice, or possible collective choice, either through multi-actor negotiation or voting | Flexible, Easygoing | Dual system. Authoritative—either group leaders or higher levels make or change rules. | Dual system. Authoritative—either group leaders or superior levels but highly clandestine | Dual system. Prison administration makes and changes rules (also, from external law and policy-making). Prisoners have their own ways for making and changing rules, but typically clandestine |

| Group Resources (IX) (materials and technologies). | Specified appropriate materials, technologies used in production and commercial activities; Sufficient financial resources (capital) for group sustainability and production. | Appropriate resources and equipment for research and development in the group’s domain (e.g., computers, special equipment, programs, laboratories). Sufficient funding base is a critical component of group knowledge production and sustainability. | Specified equipment for activities; access to activity space | Armaments, military equipment, access to territory to locate in. Sufficient funding to function effectively relative to real or potential military challenges | Weapons of destruction; safe houses. Sufficient funding to obtain weapons and to engage in preparations such as training and maintaining save houses and weaponry. | Prison administration has substantial resources of control and sanctioning. Prisoners have to smuggle in or to produce themselves many of their technologies and other materials |

| Times and Places for Group Activities (X) | Specified times and places (factory, office) for production, bur possibly with “farming out” and Flextime—thus likely fuzziness and variability. | Flexible or loose times and places for research (work). | Free time of members; identity of places accessible to members or the group as a corporate entity (club). | 24-7 readiness, military camps and offensive and defensive positions. Specified territory or territories for bases. | 24-7 readiness. Available safe group spaces, training camps | Administration has 24-7 readiness. Prisoner times and places decided by prison administration and/or courts |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burns, T.R.; Roszkowska, E.; Corte, U.; Machado Des Johansson, N. Linking Group Theory to Social Science Game Theory: Interaction Grammars, Group Subcultures and Games for Comparative Analysis. Soc. Sci. 2017, 6, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6030107

Burns TR, Roszkowska E, Corte U, Machado Des Johansson N. Linking Group Theory to Social Science Game Theory: Interaction Grammars, Group Subcultures and Games for Comparative Analysis. Social Sciences. 2017; 6(3):107. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6030107

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurns, Tom R., Ewa Roszkowska, Ugo Corte, and Nora Machado Des Johansson. 2017. "Linking Group Theory to Social Science Game Theory: Interaction Grammars, Group Subcultures and Games for Comparative Analysis" Social Sciences 6, no. 3: 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6030107

APA StyleBurns, T. R., Roszkowska, E., Corte, U., & Machado Des Johansson, N. (2017). Linking Group Theory to Social Science Game Theory: Interaction Grammars, Group Subcultures and Games for Comparative Analysis. Social Sciences, 6(3), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6030107