1. Introduction

“People of color get to have spaces. We get to have our fashion shows. We get to not need to cater to whiteness all the goddamn time.”

—Fat People of Color moderator

Fat People of Color is a Tumblr page that invites followers to submit images of themselves that are usually accompanied by thick descriptions of the photos that act as counter-narratives about fat bodies. Women of color negotiate what it means to occupy a fat body. In this paper, I will explore the discourse used by women of color to resist normative standards of beauty on social media.

As many feminist scholars have argued previously, “fat is a feminist issue” because fat and fatness challenge the unrealistic expectations of women that are presented by mainstream culture [

1,

2,

3]. However the concept of fatness, the stigmatization of fat, and resulting fat phobia are complicated. The very idea of fatness and the use of the term “fat” are contested by members of the fat activist community. Fat acceptance, body positivity, body politics, fat activism, and fat studies encompass various cultural and identity projects. Though different individuals or groups may have various ideologies and may be working toward the same goals, the methods for achieving those goals are diverse. These corporeal projects have no singular identity or theoretical basis from which they operate ([

4], p. 20). Further, the presence of multiple, interlocking, yet separate, discourses causes many scholars to question the validity of some aspects of the “movement” including the framing of the discourse as a movement. Throughout this paper I will refer to the process of achieving fat acceptance as fat activism and fat acceptance. I use these terms interchangeably, however, the terms body positivity and body politics are disputed ideas amongst scholars and the communities to which the terms are often applied. Therefore, body positive narratives are specific to the philosophy of body positivity (which encompasses health, beauty and moralist claims about fat) and are not interchangeable with fat acceptance ideologies.

As multifaceted as these issues seem, research on the topic thus far has been surprisingly monochromatic. Most of the research that focuses on the questions and inner dialogues within the fat activist framework focus on the relationships and ideas of white women [

2]. The research that comes close to understanding the position of women of color within the ongoing fat acceptance discourse comes from nursing and health journals that explore the performativity of body and preferred body type [

5,

6,

7].

Fat People of Color occupies a contested space and represents a common struggle over ideology of the fat activist movement; often, women who employ a fat-positive narrative feel conflicted about how their ideas of selfhood work against, or help achieve, the goals of fat activism. I find that Fat People of Color takes an intersectional approach, building fat acceptance and body positive discourse that is inclusive and representative of the pantheon of fat body experiences to construct counter-narratives of fatness; taking back the power to define one’s self and existence in a fat body.

This research contributes to an understudied area of sociological inquiry by presenting an analysis of the experiences of fat women of color within a feminist framework. Some feminist theories of fatness and body size are underpinned with racial and class binaries that reinforce existing hegemonic representations of lower income women and women of color ([

8], p. 95). Ignoring the variation of these experiences further upholds the types of privilege that fat activism and feminism are trying to dismantle. These differences also influence and regulate the relevance of feminism and fat activist discourse to all women, not just white women. Further, fat acceptance lifestyles are diverse and experiences vary according to race. I argue that the distinction in the way that women of color engage with fat activist frameworks suggests that women of color may view their bodies differently and abide by a different set of normative beauty ideas than do white women.

3. Methods

Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) is used to study resistance to dominant narratives in society—particularly text- and conversation-based discourse. Having roots in Frankfurt School ideology and “critical linguistics”, CDA emerged as a response to uncritical research paradigms [

23]. CDA explicitly seeks to understand how discourse mediates social inequalities and attempts to explain the underlying roots. CDA “focuses on the ways discourse structures enact, confirm, legitimate, reproduce, or challenge relations of power and dominance in society ([

23], p. 353). Adding a layer of complexity, Brock [

24] argues that Critical Technocultural Discourse Analysis (CTDA) “draws from technology studies, communication studies, and critical race theory to understand how culture shapes technologies” ([

24], p. 531) and how technologies shape culture. CTDA, as a methodology or technique, highlights the relationship and power negotiations that occur on, and through, technology. It also specifically looks at how a particular aspect of technology facilitates certain discourse. Thus, in this paper, I use CTDA to examine the fat activist framework and accompanying discourse in the fatosphere. As a network of blogs and online spaces, the fatosphere supplements mainstream body-positive discourse in media [

20]. However, for fat people of color, the fatosphere facilitates a discourse that is made possible by technology online. Without the webspace Fat People of Color (and others like it), people who are not white would be largely excluded from the fat acceptance movement. Following some of the foundational tenets of CDA and sequentially CTDA, I argue that fat activist resistance online “does ideological work” and acts as a “form of social action” ([

23], p. 353).

Fat People of Color is a Tumblr page that was founded in April of 2011. Since that time, users have created 639 individual posts about life as a fat person of color. The site invites followers to submit images of themselves that are usually accompanied by thick descriptions of photos either provided by the person featured in the image or by the moderator of the site. The posts vary by content as some are of a singular image with a description, while others are devoid of images but full of descriptive text. Both images and text serve as data for discourse analysis precisely because they provide explicit counter-narratives by combining images submitted by members of the community with descriptions of their own bodies that directly and explicitly challenge normative beauty ideals.

Using the archive function of the website, each post was individually counted, yielding a result of 639 individual posts. Though not every post is original (i.e., it may have been reblogged from another tumblr), most posts are accompanied by an original contribution that is specific to this site (via the caption or other contextual elements). Additionally, “notes”, the term Tumblr uses to connote “reposts”,”reblogs”, “comments”, and “likes”, was used to source the most influential posts. On the low end, some posts have only one note. Alternatively, the most popular image post was tagged with 87,677 notes, while the most popular text-based post was tagged with 137,462 notes. Despite the variation in activity surrounding posts, I include every post in my reading of the site because I choose to focus on the community as a whole—in that context, the numbers play a less significant role.

Each of the 639 posts were read and annotated (e.g., notes were made about specific hashtags used, style of writing, clothing choices, and references to body size and ethnic and racial identity markers)—taking care to note posts that are in conversation with each other. Discourse themes were generated using the constant comparative method. This method, based in the broadly-interpreted grounded theory approach, is concerned with suggesting themes with explanatory potential not testing specific hypotheses. Thus, each image was “read” with an eye toward author descriptions of images, as well as the positioning of the body and clothing in images. From this initial reading, major discourse themes were quite apparent. In the next step, I compared notes, as well as portions of author descriptions, to each other. As topics repeated, they confirmed existing themes. Similar images were compared to each other within categories to ensure continuity and authenticity. This iterative process resulted in the creation of three main themes and various subthemes that I discuss in

Section 4:

4.1. Everyday Resistance

4.1.1. Explicit Discourse on Exclusion

4.1.2. Fashion as Resistance to Normative Beauty Standards

4.2. Intersectional Examinations of Fat Politics

4.3. I Own My Body—Not a Fetish

To interpret these themes, I situate them socio-politically while exploring the discursive limitations and affordances associated with identity politics on Tumblr. The images that are presented here were chosen because they represented a particular theme well and, perhaps more importantly, because the people in the image gave permission for their images to be used in the context of this paper. Full written permission was granted by each of the participants to reproduce their photos. Further, all comments were collected with IRB approval. Names have also been changed to protect participants unless they explicitly asked to have their names or screen names included. To provide additional transparency and added validity to claims made here, participants were invited to read this article before publication. In the following sections I examine how participants use their images to contribute to new body identities and form an active community of support online for a generally marginalized community—fat people of color.

4. Results and Discussion: Intersectional Body Positivity

4.1. Everyday Resistance

4.1.1. Explicit Discourse on Exclusion

Fat People of Color is a technocultural tool that facilitates discourse on dominant beauty narratives for people of color that is “dedicated to encouraging and showcasing media of fat (and non-’straight sized’) people of color. [It is] anti-racist, anti-ableist, anti-classist, anti-queer hatred, anti-transphobic, and generally an all-inclusive space”. This description from a moderator is representative of the type of discourse that is facilitated by the webspace Fat People of Color. In addition to creating a space for people of color to celebrate fat identity, moderators also draw attention to white privilege that is inherent in white feminism. White women have historically excluded women of color in feminist discourse [

25]. The following posts highlight the privilege with which fat white women operate. Instead of reaffirming whiteness as the default, Fat People of Color works to unite people of color across the sexual identity, body identity, and gender identity spectrum. Moderators and community members engage in intersectional discourse to actively negotiate mass circulated rhetoric on black, brown, queer, and fat bodies.

I think my least favorite thing about the fat acceptance movement is when white people act like it is more difficult to be a white fat person than a fat person of color.

There was this post in the fatshion tag a while back about this women complaining about how the nearest store that had clothes in her size was in the ‘getto’ and she wanted acknowledgement that white women could be fat too. She didn’t want to go shop next to the scary brown women to get her bras.

And this one time there was an article about this plus size fashion show [where] most, or all of the models were people of color. And someone left a comment like, “That’s nice, but what about positive body image for white women?” I shit you not. Someone said that.

What white people have to understand is that society’s beauty standards are in favor of whiteness. Being fat does not erase you[r] white privilege by any means. Being fat does not mean you experience anything similar to racism.

People of color get to have spaces. We get to have our fashion shows. We get to not need to cater to whiteness all the goddamn time.

Nearly every body positive space I have seen is run by white people and most of the contributors are white people. White people, you have your space. Don’t complain when we won’t let you into ours.

—Beatriz

The phrase “That’s nice, but what about positive body image for white women?” highlights the need to assert whiteness into the conversation. Even in the societal margins, people of color’s ideas about their bodies are still expected to conform to standards of whiteness. Moderators play an integral role in facilitating the discursive nature of Fat People of Color. The moderators of the site work to fill the gap that Beatriz speaks about by creating a space that is inviting to all people of color, regardless of other signifiers of identity, such as class, sexuality, and gender identity. They repeatedly make mention of the space as a communal resource and a safe haven; a separate entity from the mainstream fat activist circle. Beatriz’ post also addresses another layer of meaning, the absence of intersectional approaches to fat acceptance. White women do not address other identities because they have fat white privilege that fat people of color do not. They are othered on the basis of their size but not their race. Addressing fatness as a person of color necessitates resistance of ideologies and stereotypes at meeting points of identities. In the following, FPOC moderators reposted a widely shared letter to white fat activists that explicitly addresses the need for intersectional resistance and counter-narratives about fat bodies of color.

This letter is written to our fat community to express great concern over what appears to be a growing divide among us. We continue to see fat activism growing and our community expanding, and while this brings great joy, it also becomes more and more apparent that we are not doing the work to prevent our community from being divided along race and socio-economic lines. We are not having the hard conversation needed to build the truly solid foundation of inclusivity and diversity that we rest much of our argument of anti-oppression upon. This is particularly important since both government programs and the diet industry have been specifically singling out and targeting people of color in recent campaigns…

While fat activism in the United States continues to be predominantly white, there is an emerging wave of fat People of Color (POC) activists moving out into all aspects of our communities. Joining with fat POC activists who have been working for years to create space for the unique challenges faced by POC within our mainstream diet culture, this has the potential to be a time of enormous shift in the perception and face of fat activism in the U.S. We are excited to be a part of this paradigm shift, and to see more of our experience reflected in the work of fat activism…

When open and authentic conversations about race and class fail to happen, we see these attitudes in the ways that people are left out of conversations. We see people who live with great privilege speaking as authorities on the impact of racism and classism, without basing their approach in the ally model. We see large size acceptance campaigns launched without coalition among diverse groups, thoughtful discussion around inclusivity, or well-versed allies on hand to help answer questions and facilitate community conversation. We see white allies depending heavily on POC and poor people to discern, direct, and implement the work of addressing these concerns within our communities only after or in response to work being presented that does not include their voices. We see white allies responding defensively and closing down conversations when presented with clear questions about taking steps to do their own work of finding ally mentors, addressing the ways their own acknowledged and unacknowledged privilege directly affects members of their community, and engaging in thoughtful dialogue about the interconnectedness of oppressions and the diverse ways those oppressions affect different members of our communities.

In turn, thousands have responded with letters of encouragement, affirming the idea that fat spaces for people of color are limited. The fatosphere is white and mainstream fat activism is experienced by people of color as exclusionary. Thus, the need for the Tumblr Fat People of Color is deeply recognized.

“You folks are doing a great job! I would really like to see this space remain exclusively for Fat identified people of color, because this might be the ONLY SPACE on tumblr to do both of those things. I also appreciate that this blog isn’t all about the haters, you know? I know we all catch shit from the world, but it’s not our job to educate the ignorant, and when we respond to every mean anon, the blog becomes about them and not about us.”

—Shantal

Shantal’s post not only speaks to the void of representation in fat activism, but also references anonymous posts from those who disagree with the fat acceptance agenda. In her observation, the moderators’ refusal to post and respond to dissenters contributes to the value of the space. This affordance is specific to Tumblr. The “Ask” function allows users to post questions anonymously or with their handles. Moderators of blogs can then choose to respond publicly or privately—giving the community some degree of control over who can participate in their community. In addition to protecting the community, the “Ask” function also serves as a wading pool for newcomers. If people are uncertain about the appropriateness of content, then can ask anonymously without consequence. For example, anonymous asked: “Is it okay for biracial people to submit their photos?” The moderator publicly responded in hopes of encouraging the original questioner and future inquiries.

4.1.2. Fashion as Resistance to Normative Beauty Standards

As moderators work to protect and encourage the continued growth of a much needed space for discussion and connection, users respond by submitting images of themselves that capture a variety of experiences and presentations of self. Those who post submit commentary about their images that range from everyday life, fashion, where to purchase clothing, and explicit counter-narratives that challenge existing paradigms. However, even when users are not explicit about their defiance, I argue that pride in the fat body of color resists the framework of shame that we have become accustomed to. Further, the discursive power of selfies and other actions online has already been demonstrated [

24,

26]. Posting a picture or selfie communicates information to other users who are familiar with that cultural conversation. Even when users do not explicitly caption images, they express gender, racial, and ethnic counter-frames [

26,

27]. Here, users create captions that specifically address the identity being employed. Thus, images posted on FPOC communicate layers of meaning through the image itself and the words that accompany it.

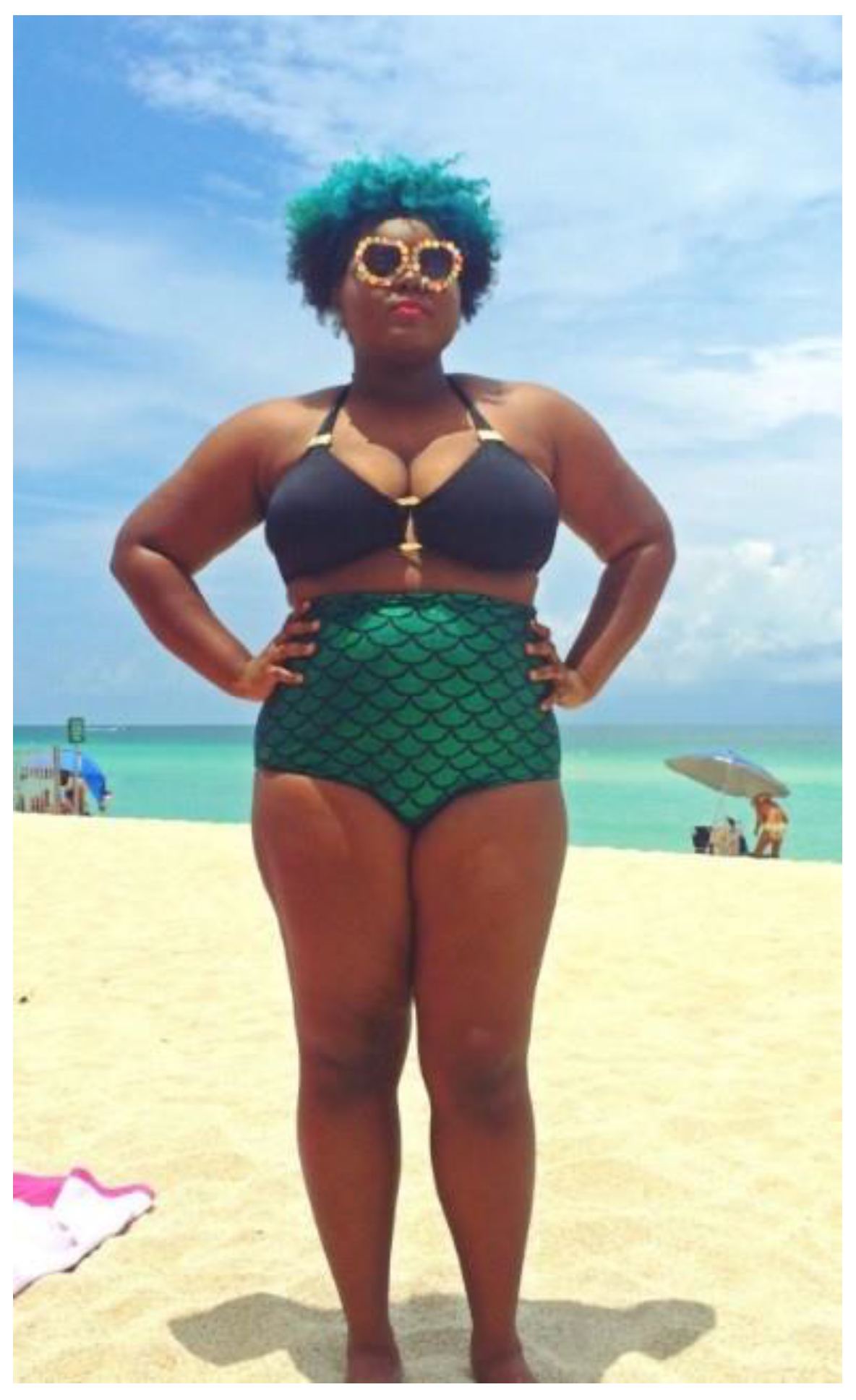

Figure 1, and the accompanying description, explicitly reference a multiethnic perspective while conveying aspects of their life story—drawing attention to the type of intersectional, radical act that is presented by fat bodies doing everyday things like getting dressed and celebrating fat bodies. As argued previously, posted images can be used to affirm one’s sense of self and to provide a buffer against commonly circulated racialized stereotypes [

26]. Unique to FPOC, however, is the nature of the space. Unlike public conversations on Twitter, public discussion and communities are moderated. Tumblr blogs, such as FPOC, represent a mediated public sphere. Users are expected to engage in an intersectional manner, as per the description of the site. Anyone who participates is expected to adhere to anti-ableist, anti-racist, and anti-sizeist discourse. Alternatively, in spaces where users coalesce around a cause via the use of a hashtag, users participate with a greater risk of encountering opposing views that may be potentially triggering.

As a result, users are free to engage in identity negotiation among users that share the goal of fat acceptance. Their identity negotiation is powerful because the people in the images are outside of what is considered normative even when they are engaging in everyday activities such as discussing fashion. Instead of being the passive recipient of other’s ideas, those who post pictures sometimes do so to reconstruct their own narratives [

26]. When FPOC community members post of a selfie or a picture of an outfit’s composition or where an outfit came from, it becomes an act of defiance for several reasons. Most obviously, positioning larger bodies as attractive and desirable defies beauty standards of thinness. The choice of clothing also communicates visual meaning to other viewers. Fat bodies have a harder time finding clothing in stores because retailers refuse to make them in sizes outside of the “normal” range. Companies that do make extended sizes usually charge women more for larger sizes while comparable sizing in men’s lines does not change in price. When clothing fits well and is enjoyable, sharing the outfit not only helps others to find clothes, wearing the item encourages retailers to continue expanding clothing sizes. Tumblr’s user interface is also useful in this regard. Users can easily repost or reblog an image and the details about where to purchase clothing to their personal blogs.

Sharing where clothing can be posted also helps build community in that people communicate about which brands honor their bodies instead of trying to hide them. Note that Guadalupe, in a crop top in

Figure 2, talks about feeling freedom. An inner freedom that has rejected other’s ideas about what a body is “supposed” to look like.

4.2. An Intersectional Examination of Fat Politics

Intersectional approaches to discourse on fatness emerged as a distinct theme and represents a large portion of the conversation that occurs on FPOC. Community members often acknowledge the intersections of their identities and harness them to further celebrate the diversity of fat bodies.

Marisole’s post (

Figure 3) discusses the additional issues that contribute to the construction of fat bodies in American media. As earlier literature has shown, fat people are viewed as lazy or morally reprehensible [

4,

10,

11]. In the minds of most, fat people are fat by choice. They choose to overeat or not to work out. Fat by choice is often not the case, as many struggle with inadequate food choices because of income constraints. Still, many are fat by choice or by some other contributing health factor and yet they are still healthy. Discourse on this webspace offers people of color a space to negotiate their own personal definition of health and size while being mindful of all of the various social roles that they occupy. Elements of Marisole’s photo and accompanying description specifically allow for a discourse on poverty

and size. Marisole’s stance is one that is resistant to the idea that women should take up less space, with legs firmly planted and hands on hips. The setting of the image, a mobile home park, also directly engages the poverty narrative that dictates that one should be ashamed of their social standing or income, and clearly she is not. The words placed over the image remove any doubt about the discursive nature of the photo: “I will never apologize for being fat brown & poor”. Instead of succumbing to the expected societal norms, Marisole has decided to resist. The 3317 reposts of this image on various blogs across Tumblr are indicative of literal and figuratively shared resistance.

4.3. Resistance to Fetishization

In addition to creating counter-narratives about fat bodies, discourse on FPOC also actively resists the fetishizing of fat bodies of color with elective disclaimers that accompany the images:

“Being positive about my body is so hard some days because truly, I’ve been told my whole life that my body is wrong and takes up too much space. But I’ve definitely come a long way. Last month, I would never have posted pictures that showed this much of my arms, stomach, thighs, etc. Last year, I would never have tied this shirt up, worn it without a tank top, and I SURE AS HELL would not have taken or posted pictures in it.

So these pictures are a giant FUCK YOU to everyone who has ever tried to make me feel bad about my body. It’s a fuck you to all of the people who wanted to like me in private because they couldn’t handle my body. It’s a fuck you to everyone who has ever offered me dieting or exercise tips that I never fucking asked for. And most of all it’s a fuck you to everyone who fetishes the fat body.

I don’t want your fucking help. I am not your fucking fetish. I will not hate my body to fit your standards.

***DONT REBLOG THIS TO YOUR FETISH/PORN BLOGS that’s not what these are for”.

—Adriana

Disclaimers like the one above are common throughout the site and are a direct commentary on the exploitative male gaze. The warning “not for porn, bbw (big beautiful women), fetish or whatever blogs” is likely posted as a result of previous images appearing in those very locations. The necessity for such disclaimers affirms previous work [

15] that theorized that fat bodies are fetishized in private. Adriana’s post also speaks to Colls’ [

4] observations—that men who fetishize fat bodies are reluctant to express interest in fat women in public: “It’s a fuck you to all of the people who wanted to like me in private because they couldn’t handle my body”.

As Adriana’s post demonstrates, fat people that participate in the fat acceptance lifestyles constantly negotiate for themselves what it means to be healthy, attractive, and fat. She alludes to the emotional labor associated with balancing these ideas and resisting dominant beauty frameworks. In addition to fatigue associated with racial macroaggressions, fat people of color also expend unnecessary energy dealing with “dieting or exercise tips that [were] never fucking asked for” or being made to feel ashamed of their body size. Another FPOC community member, Nicole (

Figure 4) uses her images to provide commentary on the fetishizing of the fat body:

Adding a layer of resistance beyond “not for porn, BBW, Fetish or whatever blogs”, Nicole also creates counter-ideology with her statement “eff your beauty standards”. Her hashtags “pinup”, “fatshion”, and “honormycurves” demonstrate that she views her black fat body as not only beautiful according to her own standards but worthy of being emulated.

This image presents an additional opportunity to explore the discursive meaning-making process that occurs on FPOC via the affordances associated with Tumblr. Hashtags become particularly important as they allow additional layers of meaning and conversation. The hashtags in the post above speak volumes about the discursive power of the webspace Fat People of Color. First, hashtags yield insight about the motivations behind posting the image. The hashtags touch on size, natural ethnic hair, beauty standards, and race. In addition to telling users outside of the community not to use their pictures for unintended purposes, Nicole also makes identity claims about natural hair, gender, and size. Next, hashtags provide a record of similar claims. Specifically, users can click on a hashtag and see what other users have said about the same subject. Thus discourse is not constrained by time. No matter how old a post is, if a user is willing, they can find similar posts from as far back as the websites origin. Users can then recall previous dialogue about similar topics, enabling discourse to transcend time. Due to the multiplicative ability of hashtags, users can communicate several different ideas at a time. Nicole communicates with other users about her body and hair both in the present, past, and future. Sequentially, visitors to the site will construct discourse with the possibility of engaging with Nicole’s hashtags. In this case, the post has been shared, reposted, or referenced nearly 25,000 times since it first appeared on Fat People of Color.

5. Conclusions

Though it is disheartening that fat activism and fat acceptance frameworks do not readily include a space for women of color, the network of fat accepting spaces of color is rapidly growing, and with it, the discourse on the intersections of race, gender, class, and body size. Fat women of color are committed to dismantling heteronormative, male-centered fat phobic imagery and ideologies by creating counter-narratives about their own bodies.

As the network of fat blogs and websites expand, it becomes easier to observe the discursive nature of sites like Fat People of Color. Cross-postings and reposts indicate just how commonplace narratives like the few I have shared are. With posts like Nicole’s having well over 24,000 reposts across various Tumblr pages, it is apparent that spaces for fat people of color are valued and cherished. Beyond being appreciated, the interconnectedness of the posts across the platform empowers people who submit their images and commentaries while also making space for a conversation about race within a predominantly white discourse.

5.1. Tumblr—Affordances and Hindrances

Technocultural discourse analysis requires an interpretation of the influence of the technology on the discourse. Thus, in using CTDA for my exploration of FPOC, I chose to conduct this study as a participant. The affordances I observe here are a result of my personal experience as a user, as well as that of the other community members in FPOC. I do not intend to claim that the affordances I have discussed here represent an exhaustive list of affordances associated with Tumblr or even this particular page. Moreover, there are several particularities of Tumblr that do not best facilitate critical discourse. As touched on above, platforms such as Twitter and Instagram offer an opportunity to dialogue with people that hold opposing views. If the goal of critical discourse is to advance a political cause, this is hard to do when political lines are not being crossed. Is there space for safety and mental wellness when working toward the advancement of a political goal? There must be. In fact, a social movement that is so focused on body politics would be remiss to compromise the mental health of participants. Still, the tension of mitigated vs. somewhat unmitigated discourse on Twitter and Instagram is tangible. In light of this tension, I theorize spaces like FPOC as a necessary safe haven where like-minded individuals can recharge for the more public battles that occur mainly online.

5.2. Limitations

In the spirit of Fat People of Color’s inclusivity, I acknowledge that the space is dedicated to more than just the liberation of fat female, cis-gender bodies. Men and gender nonconforming individuals also contribute to the wealth of this space by sharing their fat body experiences. Since this paper critiques dominant feminist frameworks, I decided to focus this initial study on women who post. Additionally, given the overabundance of women who post to the site, it seemed unfair to make generalized sentiments from such a small number of representatives. In the future, I hope to devote greater attention to the experiences of fat, queer, gender-ncf, and men of color as this area of research is gravely understudied.

5.3. Implications—Toward a New Understanding

Tumblr pages like Fat People of Color represent a framework that is divergent from normative body positivity. Moralistic discourse about health is noticeably absent, suggesting that, for women of color, ideas about fatness and size fall more closely in line with a liberationist approach that “celebrates fatness and tries to secure for the fat a positively valued experience of difference from the norm” ([

4], p. 22). Even though members use body positive language which often falls in line with assimilationist approaches, the discourse that occurs on FPOC leans heavily towards liberationist ideologies. Moreover, the intersectional approach of this space that the moderators work so diligently to cultivate, helps shape FPOC as a communal space. We have learned from earlier studies that communal or group identity may impact body image and self-esteem [

28]. Thus, communal fat spaces contribute to overall health because mental health plays an essential role.

This study also revealed some departures from previous literature on fat Latina women. According to previous literature (e.g., [

22,

29]), fat Latina women are more likely to be ashamed of fat bodies and prefer an assimilationist approach. However, I was surprised and encouraged to find that fat Latina women also participate in discourse on fat bodies of color. Whether this shift in participation is in response to less communal support offline or an indication of more familial and communal support offline cannot be concretely determined from analysis of images and text alone, but my findings suggest that fat Latina women are “fat brown & down: down for the fat poc revolution” (Vanessa, participant).

Finally, I want to draw attention to the absence of fat accepting discourse offline. This discourse is almost entirely occurring online in the “fatosphere”. The absence of these discussions in mainstream media is a form of symbolic annihilation of a great deal of fat Americans and fat Americans of color. Misrepresentation and the absence of representation of fat bodies harms all of us in the long run by presenting outlandish standards for body size and distorted, culturally-insensitive narratives about health. To conclude, I would like to acknowledge the ever-shifting nature of this research. Due to the subject matter of these platforms, the women featured here are particularly likely to shift their ideas and goals for fat acceptance as they participate in fat-accepting communities. It is not my intent to say that any one of these comments wholly represents women portrayed, nor can I fully represent the character of the platform, Fat People of Color in its entirety. The sentiments are representative of ongoing negotiation of self and others—a constant examination of several identities at once.