Abstract

Since 2009, more Mexicans have been leaving rather than coming to the USA; likewise, illegal immigration from Mexico has declined. Yet, immigration remains a hotly contested issue in the 2016 presidential election, with a seemingly marked increase in anti-immigrant policy and rhetoric, much of which is directed at immigrants from Mexico. In this paper, we seek to explain how individual ethnocultural and civic-based conceptions of what it means to be an American influence attitudes towards immigration. Past theoretical research on national identity has framed the effects of these dimensions as interactive but past empirical work has yet to demonstrate an important interaction between race and ethnocultural identity. Failure to account for these interaction effects has led to inaccurate assumptions about the levels of hostility towards immigrants and how widespread anti-immigrant sentiment really is. We demonstrate a clear interactive effect between identification as white and ethnocultural dimensions of identity and show that this effect has masked the root of the most ardent anti-immigrant sentiment. We also show that while there is a sizeable minority of the population that identifies as both white and have high levels of ethnocultural identity, a majority of Americans prefer to keep immigration levels at the status quo and have an identity that is balanced between ethnoculturalism and civic-based conceptions of identity.

1. Introduction

1.1. Controversy and Immigration

One of the most controversial topics of debate in contemporary America is immigration. This controversy has resurfaced in the context of the 2016 presidential election, with several GOP candidates promising to curtail levels of immigration, in particular Donald Trump, who has infamously introduced his candidacy with a speech labeling Mexicans as “rapists” and “drug dealers.” Trump (along with other failed GOP presidential hopefuls such as Ted Cruz) promises to build a wall to stop the flow of immigrants coming from Mexico, despite net immigration being at zero and marked declines in illegal immigration at the Sothern border [1,2,3]. With the passage of tough anti-illegal immigration in states such as Arizona, Georgia, and Alabama, “nativist extremist” groups have also been in decline after reaching their peak in 2010 [4]. Yet, arguably, the anti-immigrant fervor in America still exists and is being driven by everyday citizens largely through grassroots activism including demonstrations, protests, and pressuring state and local legislatures to pass policies that will curtail immigration [4].

Strong feelings on all sides of the issue are driven by core debates about what it means to be an American. While most people in contemporary America hold to the idea that this country is a nation that was built by immigrants in the past, there is substantial disagreement over whether this historical model applies to today’s immigrants. Debates rage over whether or not today’s immigrants can be “truly American,” within the context of a public discourse where Trump asserts that Mexico is not sending the USA its best people and calls for a ban on Muslim immigrants to the USA. The underlying assertion of this rhetoric is that these groups are unable to fit in and become Americans as previous groups of immigrants have done in the past. At the core of this debate is a question of just what we mean by “American” in this context. For example, is the concept of whiteness still important to individuals when determining their national identity, given that the demographics of the country are markedly changing from a majority white nation to a minority plurality? In the absence of agreement on these issues, the debate continues, often involving heated arguments over key policy questions.

Policy debates focus on whether or not immigrants can integrate into society, contribute to the economy, and fully participate in public life. These debates touch the basic elements of what it means to be an American: Will increased immigration from the “wrong” places erode the core values of American society? If immigrants cannot assimilate the core values of the polity, are they deserving of its full legal protection? Previous research has shown that how one understands what it means to be “truly American” has a powerful impact on policy preference. Some concepts of American identity are associated with more favorable policies towards immigration, while others are associated with less favorable policies [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

1.2. Study Objective

An extensive theoretical literature regarding attitudes towards immigrants has developed models based on dimensions of identity [5,7,8,9,10,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. In the multidimensional framework that has emerged from this literature there is a clear argument that the dimensions of identity are interactive, even though much of the empirical work has focused on models that test only independent effects of national identity and of race. This literature has focused on a normative distinction between the “good” dimensions such as civic/political and civic/republican identity, where solidarity is rooted in institutions, symbols, and ideology, and “bad” dimensions such as ethnoculturalism, a more exclusionary that defines American identity more narrowly in terms of race, ethnicity, and fixed cultural traits. Likewise, race is viewed as having an independent effect on immigration policy preferences, with being white shown to have a negative impact on support for increasing levels of immigrants and non-white often having the reverse effect. This paper extends past research by articulating a theory of the interactive effects of dimensions of identity grounded in the existing theoretical literature and explicitly testing these complex interactive effects.

Our results suggest that individuals that are white and score high on the ethnocultural dimension of national identity are more likely to want to decrease levels of immigration. In contrast to popular immigration rhetoric, both in the political campaign and in the media, most Americans support keeping immigration at its current levels and have an identity that is balanced between ethnocultural and civic-based dimensions of nationalism. Practically speaking, this means that much of the rhetoric to impose further restrictions on immigration is largely driven by a very vocal, mostly white, minority that has overwhelmingly ethnocultural views of American identity. It is also important to note that non-Hispanic whites are very mixed in their views regarding immigration, and are not as strongly negative on this issue as has been depicted in the media.

2. Research

2.1. National Identity and Attitudes Regarding Immigration

Americans have strong feelings about immigration policy. These feelings are often deeply rooted in personal identity. The strong foundation in individual identity has made it more difficult to achieve compromise, or even sensible debate, on immigration issues. Past research has demonstrated that identity plays a powerful role in influencing attitudes towards immigrants and immigration policy, both in the United States and Europe [5,6,7,10,12,14,17,21,22,23,24,25,26,27].

While a consensus exists that ideas of Americanism influence attitudes toward immigrants, a considerable body of literature has been devoted to empirically testing the normative determinants of identity. Inquiries into the component elements of American national identity have generally argued that no single scale can capture the complexity of American national identity. Most research has come to focus on the multiple traditions concept of identity [13]. An individual’s concept of identity is the result of a complex normative framework in which they may show simultaneous affinity for multiple dimensions of identity. Policy preferences are the result of the impact of this complex framework on thinking about policy choices. Policy preference is further influenced by other factors such as race, which has not yet been modeled interactively with identity. Previous research has shown that varying scores on different dimensions of identity are associated with variations in attitude toward immigrants and a host of immigration-related policies [5,7,10,12,14,17].

2.2. Three Dimensions of American Identity

To understand the complex relationship between identity and attitudes, it is important to briefly examine the nature of the dimensions of identity that have emerged in the literature. Contemporary literature conceptualizes national identity in terms of separate aspects of how members of the polity understand the characteristics of other members. Broadly, national identity has typically been conceptualized in terms of a framework that divides the basis of American unity among ascriptive traits and ideological values.1 A mix of ethnic and cultural markers such as race, ethnicity, birthplace, language and religious beliefs characterize the ascriptive dimension of identity, leading scholars to refer to it as an “ethnocultural” dimension. Civic-based dimensions emphasize more fluid concepts of identity such as state-centered, voluntaristic notions of political rights, duties, and values [7,12,20,24,26,27].

Ethnocultural identity is primarily based on aspects of citizenship that are involuntary or difficult to change setting very rigid boundaries for group membership, making it hard for individuals from out-groups to become members of the polity. For example, Smithrefers to ethnoculturalism as “ascriptive Americanism” because the important characteristics that Americans share are disproportionately “ascribed from birth” in this dimension [28]. At its core, ethnoculturalism defines the United States in explicitly racial terms, linking American identity with being White, Anglo-Saxon Protestants, while racial and ethnic differences should theoretically be absent from purely creedal conceptions of American identity [28]. Ethnic identity has been commonly associated with a xenophobic nationalism, and has been characterized as an identity that is protectionist and hostile to minority groups. Numerous studies have documented the role that ethnocultural conceptions of identity have played in shaping negative attitudes towards immigrants [28,29]. Much of the support for anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim sentiment, and current policies that restrict the rights of people based on ethnicity and religion has also been linked to strong ethnocultural identification [11,14,17,30,31].

While the ascriptive aspect of national identity is simple and straightforward, the ideological aspect is decidedly more complex, given that ideological beliefs are more fluid. These conceptions of identity base group membership on “figurative kinship” through shared acceptance of political institutions and ideological ancestors, rather than literal, kindred bloodlines. Ideological conceptions of identity are thus normally referred to as “civic” in the literature, reflecting the commitment to a shared acceptance of the norms of the polity. These bonds are derived from shared loyalty to the polity as manifested in a commitment to its core values and institutions ([32], p. 254). The civic framework thus combines elements of ideology as well as affective elements such as patriotism. In the American context these unifying ideological beliefs include a commitment to liberal ideals, broadly defined to include a commitment to a shared set of institutions [33]. A significant affective part of the civic dimension of identity is a close identification with American values: a sense of oneself as being American. For an immigrant this is comparable to a religious conversion in that it requires open and demonstrable acceptance of the norms and values of the new community [34]. As the civic dimension is associated with a shared political culture and a sense of belonging to the polity, the criteria for membership are more open and readily acquired by outsiders willing to accept the political values of American society. This has generally been taken to mean that immigrants can assimilate by adopting the shared political culture of their new homeland and, as a result, the civic dimension has theoretically been associated with positive attitudes towards immigrants [7,12,14,24,28,29].

Empirical examinations of the civic dimension, however, have demonstrated mixed results. Contrary to theoretical expectations, at times the civic dimension has been associated with negative attitudes towards immigrants [7,12,14]. This bi-dimensional framework has also been controversial in the literature as there is no consensus on the degree to which these categories are mutually exclusive. Miller [35] views these concepts as entirely exclusive and argues that they cannot be combined; consequently, if an individual emphasizes ethnic notions of national identity, civic conceptions of identity are automatically rendered less important. Conversely, Brubaker [36] contends that there are several, interrelated ways to conceptualize national identity based on ethnic and civic considerations, and that these elements are used simultaneously to attribute or deny group membership in the nation. The empirical literature has modeled these effects independently, implicitly assuming that the effect of each dimension is independent from the effects of the others. In general this approach does not fit the theoretical foundations that underpin the logic of these dimensions. Recent work by Byrne and Dixon confirms that the mixed empirical results of the impact of the civic-political dimension in past work are the result of the complex nature of the interactions between the civic-political and ethnocultural dimensions [15]. This theoretical model has the most explanatory power when interaction effects are explicitly included in empirical models of attitudes towards immigrants and there is interpretation of the conditional effects across the range of these dimensions, which is the methodological approach that we use here.

Roshwald [32] argues that there can be no clear separation between dimensions even at the theoretical level. He recognizes “blurry theoretical distinctions” between these two seemingly competitive notions of identity. While using this framework is parsimonious, nuanced insight in the analysis may be lost if nation-states or individuals are categorized as having simply one or the other type of identity formation. In practice there are conceptions of nationalism that are closer to the ethnocultural model and conceptions that more closely approximate the civic model. He further notes that:

“The notions of civic and ethnic nationalism can be used productively if understood as conceptions that both vie with one another and interact synergistically in the shaping and evolution of national identities. These interactions contribute to the production of a variety of ever-shifting nationalist syntheses that range from the xenophobic and intolerant to the accommodating and inclusive ends of the political spectrum.”([32], p. 258)

Roshwald thus makes the case for an interactive effect based on the degree to which the ideological and ascriptive aspects of identity are mutually influential, and recent research has found this to be empirically visible [15]. Theoretically, the underpinnings of an interaction between civic and ethnic nationalism has been documented. It is difficult to justify a purely civic or ethnic nationalism, for example, given that citizenship and naturalization processes are attributes of a state; even the most ethnocentric nation will have some elements of civic identity. Civic identity alone is also unlikely to hold individuals together without any personal or emotional connections to each other. As Roshwald remarks, “people have died for God and country; no one to my knowledge has ever flung himself into a hail of bullets on behalf of the American Dental Association.” [32].While the ethnocultural dimension focuses on literal blood to forge these personal bonds, the civic dimension uses “figurative blood” to build emotional connections between members of the state. For example, James Madison suggested that those soldiers who fought for independence, while not literally brothers, had become kin to one another by their service and sacrifice to the new nation. This metaphorical kinship supported a civic-based national identity for the new state, and distinguished Britons who had fought for independence and those that remained loyal to England. The idea of the USA as a “nation of immigrants” is also a form of metaphorical kinship as people from different ethnic backgrounds are linked through a commitment to mutually shared ideological principles. However, numerous examples in history show how civic conceptions of identity easily morph into ethnic conceptions, including the segregation that persisted in the U.S. Army until after 1965, the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II even those with family members serving in the armed forces, immigration quotas based on nationality. Arguably, even at the theoretical level, there is some overlap between the two typologies of national identity. Given that many national “myths” that give rise to metaphorical kinship also are rooted in ethnic and cultural values, the two identities may collapse into one another. In the United States, for instance, individuals had to be considered to be “white” in order to be eligible for citizenship. Moreover, although the civic dimension has been more associated with liberal societies that are tolerant towards cultural minorities, political theorist Will Kymlicka has documented attempts by civic nationalists to force assimilation of ethnic minorities to the dominant culture in ethnic conflicts.

The debate over the role of dimensions of identity has been further complicated in recent work by the adoption of an expanded set of dimensions. The civic dimension discussed previously focuses on the adoption of the shared political myths of the state, and defines national membership in terms of belonging to political community, rather than an ethnic group. Recent work has refined the notion of shared political myths to incorporate a division between institutional and communitarian myths of the policy. This work divides the original civic dimension into two dimensions, a civic/political dimension that focuses on loyalty to the laws and institutions of the state and a civic/republican dimension that focuses on participation in a shared community. Schildkraut [12,13] characterizes civic/republicanism as a commitment to involvement in political and social life. This means that for a person to be considered American, they must see the community as an integral part of their identity, and serve the public good. This implies that citizenship includes an obligation to participate in the activities of the community, not simply to affirm a commitment to shared institutions of the state. Civic/republican identity is more focused on civic engagement; involvement in the community provides the “glue” that links members together. Thus civic/republican ideas about citizenship are distinct enough from civic/political notions of identity to warrant their consideration as a separate dimension in a multi-dimensional framework of American national identity [13].

Most contemporary analyses of dimensions of national identity use a multi-dimensional model. This model consists of the ethnocultural dimension, a civic/political dimension, and a civic/republican dimension. These dimensions each track different aspects of what it means to be an American, with the attitude of each individual towards immigrants and immigration policy being strongly influenced by all three dimensions. Roshwald [32] argues that national identity is the product of the constant interaction and mutual influence of a range of factors, including dimensions of identity. He argues for an interactive effect between the ethnocultural and civic/political dimensions in which the perception of out-groups as unable to accept the institutions of the state reduces the impact of the institutional elements when the ethnocultural elements are strong [32]. In contrast, civic republican conceptions of national identity are expected have an independent, not an interactive, effect on national identity, and this effect is positive. Thus, the higher the level of civic republicanism in an individual’s conception of Americanism, the more likely the more likely s/he is to have more favorable views of immigrants and less restrictive views of immigration policy.

2.3. Interaction Effects between Ethnocultural and Civic/Political Identity

In this section, we further lay out the case for modeling interactive effects between the ethnocultural and civic/political dimensions of American national identity and discuss our expectations of how individual score’s on these dimensions of identity impact their attitudes towards immigration. Given the complexities of identity formation, it is understandable that there would be a significant debate over the potential for interaction effects. In principle, some or all dimensions may interact in various ways to translate affinity for various dimensions into policy preferences. We argue that an empirical test of the impact of national identity on policy preference must account for the interactive effects across dimensions. The approach in the extant literature on national identity is to assume that all dimensions are independent, thus offering no insights into the interactive effects posited in the theoretical literature. This ignores the debate over the degree of exclusivity among the dimensions found in the literature. It also ignores the arguments of qualitative studies that have suggested that the dimensions should have a conditional effect [20,32]. The issues are further confused the by the inclusion of a normative dimension to the literature that labels civic dimensions as “good” and the ethnocultural dimension as “bad” (or being exclusively responsible for the presence of negative attitudes).

The multidimensional view of national identity implies that there is a complex matrix of identity that contributes to the attitudes of citizens on specific issues. Individuals will have varying affinities for the dimensions of identity. It is possible for individuals to have widely divergent dimensional affinities. Individuals may score high on one dimension and low on another. In rare cases a person may show strong affinity for all three dimensions. The degree of interaction between these dimensions in the formation of policy preference has not previously been discussed in specific terms, with careful attention to conditional effects. We argue that such a discussion is necessary and that it has significant implications for our understanding of the impact the dimensions have on policy preference.

The interactive effect of these dimensions on policy preference derives from two elements. The first is the nature of the dimensions themselves. The second is the nature of the policy questions related to immigration. The nature of the dimensions has a strong impact on how they influence policy preference. Dimensions that share a framework of influence are likely to have an interactive effect. Those that do not are unlikely to do so. The nature of the question asked is also important. A standard question in the literature is whether immigration should increase, stay the same, or decrease. This posits a choice between the status quo (stay the same), more open immigration (increased), and more closed immigration (decreased.) The nature of this question forces a choice between current policy and alternative policies that will be seen as either favorable or unfavorable towards immigration.

Both ethnocultural and civic/political dimensions are associated with more negative policies towards immigrants in the theoretical literature regarding the role of American identity and immigration-related policy preferences and attitudes. In addition, Kunovich [10] finds in a comparative empirical analysis that, “A commitment to both forms of national identity is associated with restrictive sentiments concerning immigrants (even after controlling for perceived threat of immigrants, preferences of assimilation, and following national interests in politics) ([10], p. 588). There is some reason to believe that commitment to the polity is related to a sense of ethnocultural distinctiveness. The process of obtaining citizenship in the USA is not culturally neutral; immigrants must learn English and agree to live by the Protestant Ethic—requirements that are distinctly cultural in nature [20]. The civic/political model, thus, includes cultural elements such as language, which imply some linkages between the ethnocultural and civic/political models. Although citizenship is more open and easily acquired in the civic/political model, there tends to be a denial of cultural differences in public life, which may lead to discriminatory attitudes. Wilcox [20] cautions that a strong civic national identity readily collapses to a restrictive sense of national exclusiveness, and is thus linked to illiberal policy preferences ([20], p. 575). While there are a wide range of interactions possible given the multiple dimensions, the ethnocultural and civic/political dimensions offer the most likely areas for an interactive effect to exist. The two are mutually compatible in that one can hold the full range of ideas on both simultaneously. One can accept that people will see a greater loyalty to the polity in those who are in the community that most reflects the dominant group within that polity. Whether rationalized through culture, religion, or some other mechanism, it is not a stretch to see how a person could score high levels of ethnocultural and civic/political elements. While they might be able to hold these ideas, their attitudes towards immigration are likely to reflect a complex thought process.

Civic/political traits can thus be considered to be exclusionary, making them more clearly closed to outside groups. This implies that strong civic/political affinity would be associated with more negative attitudes towards immigrants. We concur with Wilcox’s [20] argument about the influence of the civic/political dimension on preference for restrictive policies. This suggests strong support for the argument that civic/political affinity will be associated with negative attitudes towards immigrants and that an interactive effect should exist between the civic/political and ethnocultural dimensions.

An interactive relationship between civic/political and ethnocultural dimensions should thus show that the effect of each dimension on the likelihood of passing each threshold point weakens as the other dimension score rises. The two dimensions will each have the effect of increasing preference for restrictive policies. The effect of each will be conditioned on the level of affinity on the other dimension as the joint likelihood of a restrictive response rises. Higher levels of affinity on the conditioning dimension will reduce the impact of a unit change on the other dimension. If you are already predisposed to prefer restrictions on immigration due to a strong ethnocultural affinity, your strong civic/political affinity will have less impact and vice-versa.

2.4. An Interactive Effect: Ethnocultural Identity and Race

One of the most prominent indicators of attitudes regarding immigrants is race, and its impact has been examined in many contexts including the impact of the race of the respondent on attitudes, the impact of the racial composition of the respondent’s neighborhood or state, and even how exposure to specific racial cues can impact. For example, one experimental study demonstrated that the identification of immigrants as members of a racial or ethnic out-group contributed to negative attitudes regarding immigration because it caused anxiety among individuals [37]. Another study concluded that one is more susceptible to immigration rhetoric based on one’s identification with a specific racial or ethnic group [38]. Being in proximity to a racial group may lead to increased positive attitudes and views supportive of a more open immigration policy as is the case for Anglos who live near large Asian populations [39]. More straightforward narratives indicate a causal relationship between racial identity and attitudes towards immigration; white individuals may be motivated to evaluate immigrants more negatively, and consequently favor more restrictive immigration policies, may be motivated by perceived loss of status or by outright prejudice [40]. In whatever context racial and ethnic identity variables appear, they are presented as having a linear impact on attitudes towards immigration policy. However, we contend that race should interact with national identity, particularly ethnocultural identity, rather than having completely independent effects on attitudes. According to Fussell [41]:

“McDaniel argues that the true cause of anti-immigrant sentiment among non-Hispanic white Christians is not their religious denomination per se, but rather adherence to ‘Christian nationalism’, or the belief that America has a divinely inspired mission and its success depends on finding God’s favor. Indeed, those who hold values such as individualism, pride in being American, and ethnocentrism—all associated with political conservatism—tend to express more anti-immigrant sentiment and preferences for restrictive immigration policies.”([41], p. 489)

In fact, the results of the empirical research are often mixed and inconsistent, presenting a complex relationship with considerable variation. For example, Fussell [41] argues that there is “accumulated evidence” in the literature suggesting that non-Hispanic whites’ attitudes towards Latino and Asian immigrants is akin to prejudice against African-Americans, but not nearly as pervasive. Berg [42] cites that the attitudes of white Americans regarding immigration are particularly mixed with some supporting increased levels of immigration, some supporting decreased levels of immigration, and many supporting the status quo. White Americans are also mixed in their evaluation of the characteristic of immigrants including whether they are hard-working, commit crimes and impact the economy negatively or positively. We posit that non-Hispanic whites with a higher score on the ethnocultural dimension of national identity are likely to have more restrictive views regarding immigration policy, but that whites with lower scores on the ethnocultural dimension will be more likely to support the status quo, rather than reducing the number of immigrants admitted each year.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Dependent Variable

The dependent variable in our analysis is the response to a question asking whether immigration should be increased, left the same, or decreased.2 This variable is a three-point categorical scale with the low value (0) reflecting the response “increased”, the middle value (1) reflecting the response “left the same”, and the highest value (2) reflecting the response “decreased”. Higher scores on this scale reflect a greater desire to restrict immigration on the part of the respondent. A higher score thus reflects more hostile attitudes towards immigration.

3.2. Data

The data set used for this study is based on the 21st Century Americanism Survey (CAS) [43]. This survey was a national random sample telephone survey of 2800 respondents conducted in 2004. The survey included an oversample of minority respondents from the following groups: African-Americans (300), Latinos (441), and Asian-Americans (299).3 The large number of minority respondents included in the survey and the inclusion of more indicators to tap the content of American national identity represent significant demographic improvements upon earlier surveys [13]. The 21st CAS tapped the politically engaged and informed tenets of civic republicanism more directly through four new indicators specifically intended to capture this dimension [13,44,45]. Improved question wording also allowed the capture of more precise data on the ethnocultural and civic/political dimensions. This survey represents a significant improvement over past survey such as the GSS in the empirical analysis of American national identity.

The data and relevant STATA code for this paper are provided for the purpose of replication. The details can be found at the end of the paper text under “Supplemental Materials.”

3.3. Measures

To construct the standardized dimension scores that serve as the main independent variables a battery of questions was used based on the following question:

“I’m going to read a list of things that people say are important in making someone an American. Would you say that it should be very important, somewhat important, somewhat unimportant, or very unimportant in making someone a true American?”

Overall, we identify 14 indicators relating to the dimensions of interest. Following the conventions of the previous literature these were combined in a factor analysis to determine whether the indicators that cohere together in theory will cohere together in practice.4 The results of the factor analysis are presented below in Table 1:

Table 1.

Factor analysis results.

The results from the factor analysis support three dimensions of American national identity: ethnoculturalism, civic/political, and civic/republican.5 The responses to the questions corresponding to each dimension were aggregated to form a standardized scale for each dimension of identity with a score on each of the three dimensions of identity that ranges from zero to one.6 The variables have been scaled such that higher numerical values represent higher support for the dimension captured be each of the three scales. To test our hypotheses we generated multiplicative interaction terms for the combinations of the dimensions as well as the combination of the ethnocultural and white race dummy variables.7 Past results [15] had indicated that there was a potential interaction between ethnoculturalism and race. A range of control variables have been included in the models to account for a range of alternate theoretical explanations for the respondents’ preferences. The first set of control variables consists of demographic indicators including whether or not the respondent was born in the USA, the respondent’s race, gender, age, education, and ideology. The second set of control variables taps the role that economic threat plays in shaping attitudes towards immigration policy. The respondent’s income has been included to account for the economic circumstances of the respondent, and is accompanied by the subjects’ response to a question designed to capture the view of the overall state of the economy [8,44,47].8 Finally, it has been acknowledged in the literature that resentment and contextual effects are predictors of attitudes towards immigration policy [14,39,44,48,49,50]. To tap notions of anti-minority affect, respondents are asked whether they agree with the statement that an America where most people are not white is bothersome. Responses were recorded using a four-point scale with higher scores reflecting stronger agreement that a non-white America was bothersome. Finally, a dummy variable is included to capture whether or not the respondent lives in an all-white neighborhood. Table 2 contains the summary statistics for the included variables.

Table 2.

Summary statistics.

Given the nature of our dependent variable, we use a form of ordinal logit model to test our hypotheses. Traditional regression models are not appropriate with ordinal data as they make a number of assumptions that can produce biased results, most notably the linear prediction and the assumption that a move from zero to one reflects the same change in state as a move from one to two. As the threshold effects in an ordinal variable matter for our hypotheses, this weakness is of particular concern. Standard ordinal logit models account for this to some degree, but make the problematic assumption that the slopes of the coefficients are identical across all values of the dependent variable. This parallel regressions assumption is often incorrect in real-world data and can lead to biased results [51,52,53]. To account for the possibility of non-proportional odds, we estimate our models using the unconstrained partial proportions (UPP) ordinal logit model.9 From our past research, we expect to find a significant interaction effect between the ethnocultural and civic/political dimensions. In addition, we expect to find a significant interactive effect between the ethnocultural dimension and being a member of the white racial category. We estimated a series of models for all possible interaction effect combinations among the dimensions of identity to test for the possibility of complex interaction effects in the model. In the interest of parsimony, we present only the four main models in our results.10

3.4. Results

The conditional effects captured by the interaction terms are difficult to interpret from the coefficients in the standard tables presented in most research. The use of only the coefficients can lead to misinterpretation of the data as this does not show the conditional relationships at various levels of the component variables. This is especially true when the zero value on one or both of the variables of interest does not represent an observed value of the variable as is the case in our measures. In our model, there is no observed zero value for the dimensional scores meaning that the coefficients as normally presented cannot be meaningfully interpreted beyond simply stating that the interaction effect is significant [54]. To appropriately explain the conditional effects observed in the model a series of figures were generated to provide additional clarification of the interactive effects.

Table 3 contains the detailed results of the four main models. Model 4 is the primary model of interest as it contains the full results. Models 1, 2, and 3 are included to show how the inclusion of the interaction terms impacts the results. Model 1 is the base model without interactions. Model 2 contains only the interaction term for the dimensions of identity which were determined to be significant.11 Model 3 contains only the interaction term between the white race dummy variable and the ethnocultural dimension. Model 4 contains both interaction terms.12

Table 3.

The relationship of citizenship dimensions on attitudes towards immigration: a partial proportions ordinal logit model.

The included control variables show consistent results across the models with the exception of education, which just barely crosses the threshold of statistical significance in Model 3. The variables of interest show consistent results given the complexities of interpretation of the coefficients in the interactive models. In Model 3, the ethnocultural dimension is not statistically significant, but the coefficient and standard error in this model reflect the impact when the interacted variable is at zero. In this case, this means that the ethnocultural dimension coefficient applies only to non-whites. While this is interesting, the effect is more accurately modeled in Model 4 where the interaction term incorporates both the independent and interactive effects in the context of the multiple interactions.

Our models are consistent with our past findings of an interactive relationship between the civic political and the ethnocultural dimensions. In addition, we find that the ethnocultural and white racial dummy variables also share a conditional relationship.13 The results of our models provide general support for the relationship between the ethnocultural dimension and whiteness.

Results are logistic regression coefficients with the standard errors in parentheses. Coefficients and standard errors correspond to the response “immigration should be increased.” Unless otherwise noted, the proportional odds assumption holds for the variable in question. Where proportionality does not hold, the “Stay the same” response is included to show the comparison between this response and the final category “immigration should be decreased.” This model was estimated in Stata v11 using the command gologit2 [51].

The results of the model confirm the findings of past research. They also confirm that the interaction effect between the ethnocultural index and the variable for white race is statistically significant and positive. This indicates that the impact of each variable rises as the other rises. The coefficients for the component dimension scores of the interaction term reflect the effect of the variable when the other component is at zero and thus cannot be meaningfully interpreted by simply using the coefficient displayed in the table. The conditional coefficients and z-ratios are necessary for proper interpretation of the impact of the interacted variables [54]. In addition, a table of predicted probabilities is more useful when presenting the practical impact of the models.

What Table 3 can tell us is that the interaction term for the ethnocultural/civic political interaction is statistically significant and negative, and that the ethnocultural/whiteness interaction is statistically significant and positive. The significant interaction terms demonstrates that there is an interactive effect in the expected direction in both cases.

Table 3 also demonstrates that a number of competing potential explanations, such as economic threat and income levels are not significant. Variables for anti-minority affect and ideology also influence the probability of choosing the “decrease” response. The dimensions of identity and race have a significant effect on the response to the question about preferred immigration levels. The figures that follow explore the details of that relationship as well as the impact of these factors in practical terms.

When analyzing multiplicative interaction terms it is necessary to evaluate conditional relationships and their effects. The impact of one variable depends on the value of the other variable. While this is often framed in terms of the substantive impact, it also includes the possibility that statistical significance varies across values of the conditioning variable. In short, it is possible for a variable to be statistically significant at one value of another variable and statistically insignificant at a different value of that variable. To explore these conditional effects, the conditional z-ratio of an interaction’s terms needs to be examined. The simplest way to show these relationships is through graphing the conditional z-ratios and visually representing the effect as it varies across the levels of the conditioning variable. Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the conditional z-ratios for our variables of interest.

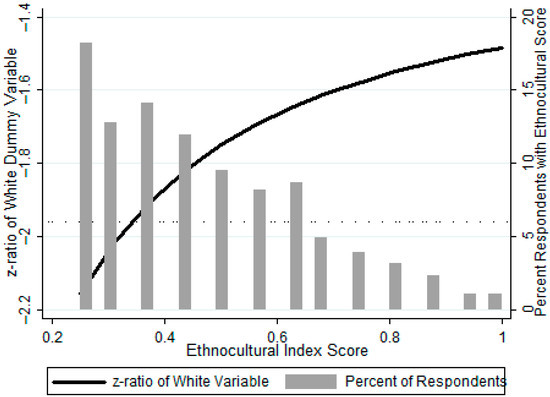

Figure 1.

Conditional z-ratio for the white dummy variable.

Figure 2.

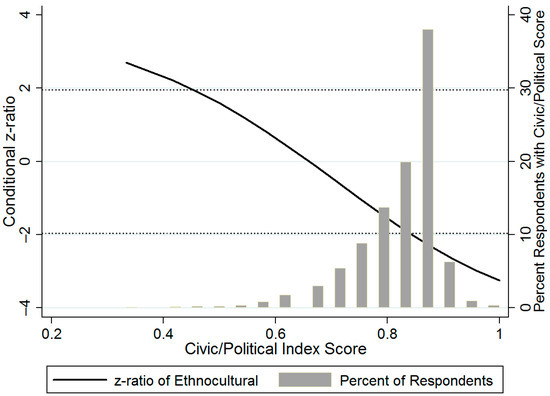

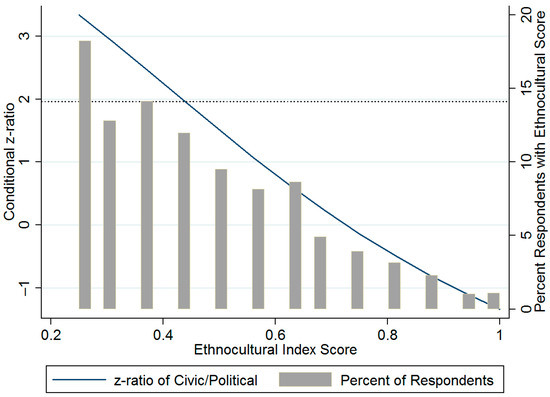

Conditional z-ratio for the ethnocultural dimension score.

Figure 3.

Conditional z-ratio for the civic/political dimension score.

To properly interpret the interactive effect requires us to look at the conditional z-ratios of the value of one variable at various levels of the other [54]. The conditional z-ratio values for the dummy variable for white racial identity are displayed in Figure 1.14 The x-axis on the figure represents the score on the ethnocultural index scale. The left hand y axis indicates the value of the z-ratio for the dummy variable. To show the frequency distribution of actual responses, a histogram showing the percent of respondents at the given level of the ethnocultural index is also included as the right hand y-axis. Figure 1 shows that the z-ratio of the white race variable is statistically significant only at low levels on the ethnocultural index. The dotted line represents the point at which the z-ratio crosses into statistical significance. While this represents a narrow range of potential values, the range includes roughly a third of the population of observations.

In these cases, identifying as white increased the (limited) effect of ethnocultural identity on the preference for restrictions on immigration.

Figure 2 and Figure 3 represent the conditional z-ratios for the ethnocultural and civic/political index scores based on the interaction between these dimensions. These results are consistent with our prior work and are included for illustrative purposes. As in Figure 1, these include histograms to show the frequency distributions of the observations.

Statistical significance of the ethnocultural dimension varies across the range of the civic/political index scores. It is important to note that the distribution of scores on the civic/political index is relatively narrow compared to that of the ethnocultural dimension. Americans tend to have a strong commitment to our political institutions, leading to a clustering of scores at the top end of the index. In this case, the vast majority of observations in which the ethnocultural dimension is statistically significant occur at the higher end of the civic/political scale.

The conditional effect of the civic/political index score is only significant at the low levels of ethnoculturalism, but the wider distribution of scores means that the lower scores include a large minority of the observations as a whole.

Figure 1 and Figure 2 show that the conditional impact of the two scales is very different. When controlling for the conditional effects of the other index, the range of scores for which the scales are significant are narrow, but in both cases, this includes a substantial number of actual observations. The civic/political dimension only impacts the preference for immigration policy at low levels of ethnoculturalism. The impact of ethnoculturalism is significant at both very low and very high levels of the civic/political dimension, but only at the high end do we see meaningful numbers of respondents. The different distributions of the scaled scores mean that the practical impact of this distribution is different for the two indices. In practice, ethnoculturalism is significant in about half of the cases, and only where the civic/political scores are high. The civic political dimension is significant in only about a third of cases, all at the low end of the ethnocultural index distribution.

The conditional coefficients in these models can be difficult to interpret in practical terms. Log odds ratios do not have a readily interpretable meaning for most people and can be confusing. To present the substantive results in a parsimonious and easier to interpret manner, we include Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 to show the predicted responses that emerge from the model under various conditions. These figures refer to the three potential outcome categories of our dependent variable: “Immigration should be increased,” “Immigration should stay the same,” and “Immigration should be decreased.”

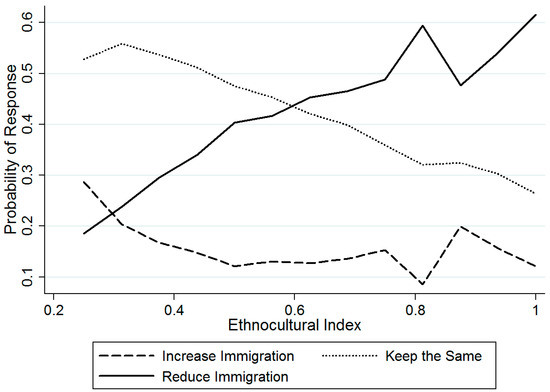

Figure 4.

Predicted probability of response based on ethnocultural index score.

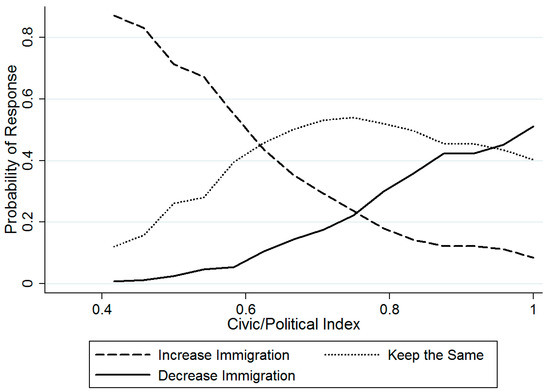

Figure 5.

Predicted probability of response based on civic/political index score.

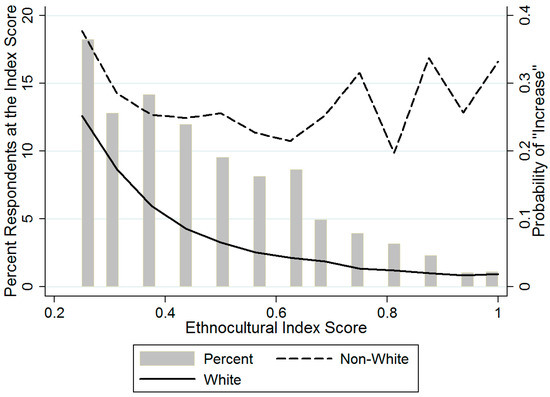

Figure 6.

Predicted probability of “increase” response by race and ethnocultural index score.

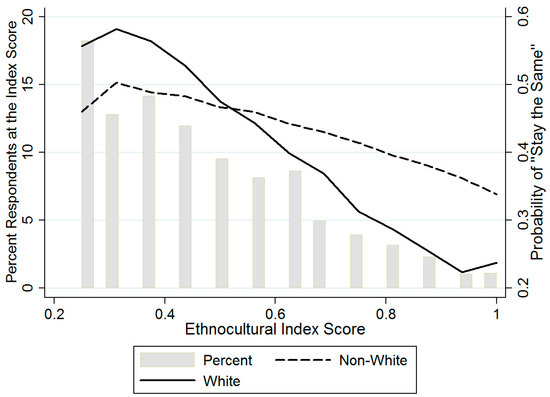

Figure 7.

Predicted probability of “stay the same” response by race and ethnocultural index score.

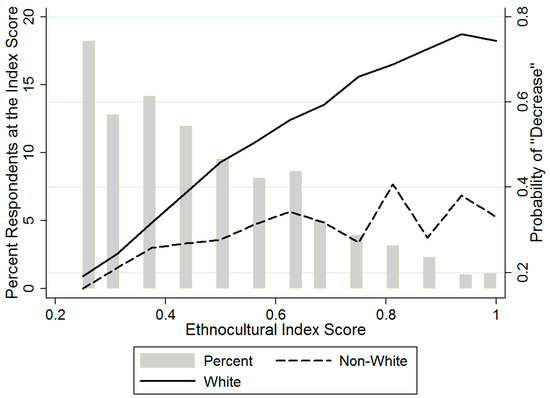

Figure 8.

Predicted probability of “decrease” response by race and ethnocultural index score.

Figure 4 displays the predicted probability of a response in each of the three outcome categories based on changes in the score on the ethnocultural index. This figure shows that the likelihood of both the increase and stay the same responses categories decreases as ethnocultural index scores rise, all else being equal. The likelihood of responding that immigration should be decreased rises significantly as the ethnocultural index score rises. The probability of advocating reduced immigration nearly triples across the range of observed values. This shows the practical impact of growing ethnocultural identity on preferences regarding immigration.

While the probability of selecting the responses does show significant change across the range of ethnocultural index scores, it is important to recall that the ethnocultural index is widely distributed, but with more scores at the low end of the scale and only a few scores at the high end. This suggests that for most of the population, the preference for the status quo is stronger than for restrictions on immigration.

Figure 5 displays the predicted probabilities of the three responses at varying levels of the civic/political dimension. These values show that there is a strong tendency to select the status quo across the range of most commonly observed values of the civic/political dimension. The tighter clustering of the civic/political dimension scores means that the vast majority of observations appear in the zone in which the highest probability response is the status quo, although the difference between the status quo and reduced immigration is relatively narrow. Only in those with the highest civic/political scores do we see the restrictive category becoming the most commonly selected response. This group represents only a tiny fraction of the respondents. While there is a general shift towards more restrictive responses as the civic/political dimension score increases, the status quo remains the most probable outcome in the vast majority of observations.

Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 are of the most interest in this project. These show the impact of white racial identity on the predicted outcome category. These three figures each show the predicted outcome for whites and non-whites at various levels of the ethnocultural index score. They also include the histogram to show the frequency distributions.

Figure 6 shows a fairly strong gap between Whites and members of other races when it comes to preference for increased immigration. While there is no range in which the predicted probability of the “increase” response is a majority of the observations, the probability does hold between 20% and 30% for non-Whites across the range of index scores. For Whites, the score falls across the range of scores, with the probability reaching under the percent in about two-thirds of cases.

Figure 7 shows the impact of race on the preference for the status quo. Interestingly, the probability of preferring the status quo is above fifty percent for nearly half of Whites. The status quo bias among whites is quite strong for a significant portion of the population. For non-whites status quo bias is less strong, but it also declines at a lower rate at the ethnocultural index score rises.

Figure 8 shows the results for the impact of ethnoculturalism on the probability of preferring reduced immigration. Here we observe that the probability of preferring reduced immigration increases at a relatively rapid rate as ethnoculturalism rises, but only rises above fifty percent in about a third of observations at the highest level of the index. In practice, most whites prefer the status quo to reductions in immigration. For non-Whites, the probability of preferring reduced immigration never comes close to fifty percent.

All three figures show a similar trend. Whites are more likely to favor restrictive immigration policies than are non-whites. As the ethnocultural index score increases, the probability of whites holding favorable views declines more rapidly than that for non-whites. Similarly, the support for reduced immigration among whites grows more rapidly as ethnocultural index scores increase than it does for non-whites. In all three figures, whites show less favorable views than non-whites and this relationship holds across all levels of ethnoculturalism. These results show the independent effect of white identity remains an important factor even when controlling for the relationship between white identity and strong ethnocultural identity. While there is a strong status quo bias in the “stay the same” response among low-ethnocultural index scoring whites, the slope of the change in the probability of the response is much steeper than that seen in the non-white population.

These results show strong support for both an independent impact of white identity on the support for immigration policies and an effect conditioned by ethnocultural identity. At first glance this appears to support the general narrative of white anger towards immigration as well as the impact of strong ethnocultural identity. Appeals to this kind of identity often present the position as one that is widely held.

While supporting the impact of ethnoculturalism and race on preferences for restrictive immigration policies, our results suggest that the story is not as simple as strongly ethnocultural whites driving restrictive immigration policy. In practice, white identity increases the likelihood that a given individual will favor more restrictive policies, but the most likely choice predicted by the model is the “stay the same” response for most of the observations actually recorded. While the high-ethnocultural index scoring respondents were significantly more hostile towards immigration, they also represent a relatively small proportion of the population.

4. Conclusions

This paper makes two substantial contributions to the literature on dimensions of identity. The first is to empirically confirm the presence of an interaction effect between the ethnocultural and civic/political dimensions and only between those dimensions. The second is to demonstrate the complexity of the interaction effect and its potential impact on policy preferences by providing details of the conditional effects. While the first element builds on previous work, the second has been unexplored in the literature. This has been a potentially important omission as our results show that a failure to account for conditional effects may lead to significant variations in outcomes. Our work suggests that simple solutions aimed at shifting attitudes about what it means to be an American may face serious challenges in practice.

Our findings also suggest that the strongest impact of ethnocultural identity is limited in practice to a relatively small portion of the population. While strongly ethnocultural whites are predicted to be strongly in favor of immigration, there are not very many of them. The most preferred category for all groups is the status quo. Not exactly surprising given the general status quo bias in policy discussions, but definitely counter to a great deal of recent rhetoric. If the majority of Americans will choose the status quo when given the chance, it is not necessary to make major changes to how people feel to prevent restrictive policies. It is only necessary to engage people in the political process.

Our findings are limited in that we only examine a single policy question and use only one survey, but we demonstrate that the qualitative critique of relatively simple empirical models appears to have merit. Our findings also suggest that those who hope to find ways of reducing anti-immigration preferences in the public will need to consider the complexities of national identity carefully. The hope that building strong affinity for political institutions would erode the impact of ethnocultural affinity appears, in light of our findings, to be overly simplistic in most cases. Shaping attitudes will require careful consideration of how various forms of national identity interact with each other. To further explore the effects of an interactive, multidimensional American national identity and its impact on immigration, there is a need for is more and better surveys, ideally surveys conducted over time and designed to capture the interconnection of dimensions. While the 21st CAS is a significant improvement over the data available for use in past research, it remains a snapshot of America at the time of the survey. Comparison with previous work using other surveys places limits on how far our findings can take us.

This paper demonstrates that policy preferences emerge from a complex set of related factors. Policy preferences are shaped by multiple factors, and these factors are not independent of each other. Empirical studies have to focus on the complex conditional effects of these dimensions if they are to serve as guides to policy. This must also include a more systematic examination of the way that policy preferences emerge from identity.

While this paper includes a great deal of methodological jargon, the basic idea is simple: to understand how a person’s beliefs about who they are and who is allowed into their group impact the policies they support, one must look at how the components of self-definition and group definition work in combination. In this study, we put this into quantitative terms and we show how race combines with more complex ideas about group identity to inform immigration policy preferences. Our findings show both the expected—that whites with a strong sense of ethnocultural identity are likely to favor restrictions on immigration—and the unexpected: the influence of ethnocultural identity is limited to a relatively small portion of the population. While our results look only at one survey, the insights can aid in the design of future survey instruments and (at least in the hopes of the authors) help to design policies that will more effectively address concerns about immigration.

Supplementary Materials

The raw data is included for replication. This file is named “byrne.dixon.ss.2016.dta” and was created in STATA 11. The STATA code to replicate the findings is included as plain text in the file “byrne.dixon.ss.2016.txt”.

Author Contributions

Jennifer Byrne and Gregory C. Dixon conceptualized and designed this study. Jennifer Byrne wrote the introduction, the literature review and selected the data source. Gregory C. Dixon ran the models, reported the data and conclusions, and prepared the graphs and figures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ana Gonzalez-Barrera. “More Mexicans Leaving Than Coming to the U.S.” Pew Research Center. 19 November 2015. Available online: http://www.pewhispanic.org/2015/11/19/more-mexicans-leaving-than-coming-to-the-u-s/ (accessed on 14 September 2016).

- Ana Gonzalez-Barrera, and Jens Manuel Krogstad. “What We Know About Illegal Immigration From Mexico.” Pew Research Center. 20 November 2015. Available online: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/11/20/what-we-know-about-illegal-immigration-from-mexico/ (accessed on 14 September 2016).

- Daniel Strauss. “Trump Fumes as Cruz Steals Wall Mojo.” Politico. 6 January 2016. Available online: http://www.politico.com/story/2016/01/ted-cruz-donald-trump-border-wall-mexico-217372 (accessed on 14 September 2016).

- Lauren Fox. “Anti-Immigrant Hate Coming From Everyday Americans.” US World Report and News. 24 July 2014. Available online: http://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2014/07/24/anti-immigrant-hate-coming-from-everyday-americans (accessed on 14 September 2016).

- Jennifer Byrne. “National Identity and Attitudes toward Immigrants in a ‘Multicreedal’ America.” Politics & Policy 39 (2011): 485–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack Citrin, Beth Reginold, and Donald P. Green. “American Identity and the Politics of Ethnic Change.” Journal of Politics 52 (1990): 1124–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack Citrin, Cara Wong, and Brian Duff. “The Meaning of American National Identity: Patterns of Ethic Conflict and Consensus.” In Social Identity, Inter-Group Conflict, and Conflict Resolution. Edited by Richard D. Ashmore, Lee Jussim and David Wilder. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas Epenshade, and Katherine Hempstead. “Contemporary American Attitudes towards Immigration.” International Migration Review 30 (1996): 535–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John Freindreis, and Raymond Tatalovich. “Who Supports English-Only Laws? Evidence from the 1992 National Election Study.” Social Science Quarterly 78 (1997): 416–40. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Kunovich. “The Sources of Consequences of National Identification.” American Sociological Review 74 (2009): 573–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deborah J. Schildkraut. “The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same: American Identity and Mass and Elite Responses to 9/11.” Political Psychology 23 (2002): 511–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deborah J. Schildkraut. Press One for English: Language Policy, Public Opinion and American Identity. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Deborah J. Schildkraut. “Defining American Identity in the 21st Century: How Much There Is There? ” Journal of Politics 69 (2007): 597–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deborah J. Schildkraut. Americanism in the 21st Century: Public Opinion in the Age of Immigration. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jennifer Byrne, and Gregory C. Dixon. “Reevaluating American Attitudes toward Immigrants in the Twenty-First Century: The Role of a Multicreedal National Identity.” Politics & Policy 41 (2013): 83–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack Citrin, Donald P. Green, Christopher Muste, and Cara Wong. “Public Opinion toward Immigration Reform: The Role of Economic Motivations.” Journal of Politics 59 (1994): 858–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deborah J. Schildkraut. “The Dynamics of Public Opinion on Ethnic Profiling After 9/11: ‘Results from a Survey Experiment.” American Behavioral Scientist 53 (2009): 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonie Huddy, and Nadia Khatib. “American Patriotism, National Identity, and Political Involvement.” American Journal of Political Science 51 (2007): 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizabeth Theiss-Morse. Who Counts as an American? The Boundaries of National Identity. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shelley Wilcox. “Culture, National Identity, and Admission to Citizenship.” Social Theory and Practice 30 (2004): 559–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victoria M. Esses, Ulrich Wagner, Carina Wolf, Mattias Preiser, and Christopher J. Wilbur. “Perceptions of National Identity and Attitudes toward Immigrants and Immigration in Canada and Germany.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 30 (2006): 653–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jens Hainmuller, and Michael J. Hiscox. “Educated Preferences: Explaining Attitudes toward Immigration in Europe.” International Organization 61 (2007): 399–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony F. Heath, and James R. Tilley. “British National Identity and Attitudes towards Immigration.” International Journal on Multicultural Societies 7 (2005): 119–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mikael Hjern. “National Identities, National Pride and Xenophobia: A Comparison of Four Western Countries.” Acta Sociologica 41 (1998): 335–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel Huntington. Who Are We? The Challenges to America’s National Identity. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Frank Jones, and Phillip Smith. “Diversity and Community in National Identities: An Explanatory Analysis of a Cross-National Patterns.” Journal of Sociology 37 (2001): 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank Jones, and Phillip Smith. “Individual and Societal Bases of National Identity: A Comparative Multi-Level Analysis.” European Sociological Review 17 (2001): 103–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers M. Smith. Civic Ideals: Conflicting Versions of Citizenship in U.S. History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers M. Smith. “The Limits of Liberal Citizenship.” The Western Political Quarterly 41 (1988): 225–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darren W. Davis, and Brian D. Silver. “Civil Liberties versus Security: Public Opinion in the Context of the Terrorist Attacks on America.” American Journal of Political Science 48 (2004): 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelle Malkin. “Racial Profiling: A Matter of Survival.” USA Today. 17 August 2004. Available online: http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/opinion/editorials/2004-08-16-racial-profiling_x.htm (accessed on 14 September 2016).

- Aviel Roshwald. The Endurance of Nationalism: Ancient Roots and Modern Dilemmas. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Noah M. J. Pickus. “To Make Natural: Creating Citizens for the 21st Century.” In Immigration and Citizenship in the 21st Century. Edited by Noah M. J. Pickus. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Peter Salins. Assimilation: American Style. New York: Basic Books, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- David I. Miller. Citizenship and National Identity. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers Brubaker. Ethnicities without Groups. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ted Brader, Nicholas Valentino, and Elizabeth Suhay. “Is it Immigration or Immigrants? The Emotional Influence of Groups and Public Opinion and Political Action.” The American Journal of Political Science 52 (2008): 959–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethany Albertson, and Shana K. Gadarian. “Anxiety, Immigration and the Search for Information.” Political Psychology 35 (2013): 133–64. [Google Scholar]

- M. V. Hood III, Irwin L. Morris, and Kurt A. Shirkey. “Quedate O Vente!: Uncovering the Determinants of Hispanic Public Opinion Toward Immigration.” Political Research Quarterly 50 (1997): 627–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel J. Hopkins. “National Debates: Local Responses: The Origins of Local Concern about Immigration in Britain and the United States.” British Journal of Political Science 41 (2011): 499–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizabeth Fussell. “Warmth of the Welcome: Attitudes towards Immigrants and Immigration Policy.” Annual Review of Sociology, 2014, 479–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justin Berg. “Explaining Attitudes towards Immigrants and Immigration Policy: A Review of the Literature.” Sociology Compass 9 (2015): 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deborah Schildkraut, and Ashley Grosse. “21st Century Americanism: Nationally Representative Survey of the United States Population.” ICPSR 27601. Medford, MA, USA: Social and Economic Sciences Research Center, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pamela Conover, Ivor Crewe, and Donald Searing. “The Nature of Citizenship in the United States and Great Britain: Empirical Comments on Theoretical Themes.” The Journal of Politics 53 (1991): 800–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter Burns, and James G. Gimpel. “Economic Insecurity, Prejudicial Stereotypes, and Public Opinion on Immigration.” Political Science Quarterly 115 (2000): 201–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tim Reeskens, and Marc Hooghe. “Beyond the civic–ethnic dichotomy: Investigating the structure of citizenship concepts across thirty-three countries.” Nations and Nationalism 16 (2010): 579–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin Morris. “African American Voting on Proposition 187: Rethinking the Prevalence of Inter-Minority Conflict.” Political Research Quarterly 53 (2000): 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas J. Espenshade, and Charles A. Calhoun. “An Analysis of Public Opinion toward Undocumented Immigration.” Population Research and Policy Review 13 (1993): 189–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David O. Sears, and Patrick J. Henry. “Ethnic Identity and Group Threat in American Politics.” The Political Psychologist 4 (1999): 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sharmaine Vindange, and David O. Sears. “The Foundations of Public Opinion toward Immigration Policy: Group Conflict or Symbolic Politics.” In Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Midwestern Political Science Association, Chicago, IL, USA, 5–8 April 1995.

- Richard Williams. “Generalized Ordered Logit/Partial Proportional Odds Models for Models with Ordinal Dependent Variables.” The Stata Journal 6 (2007): 58–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford S. Jones, and Chad Westerland. “Order Matters?: Alternatives to Conventional Practices for Ordinal Response Categorical Variables.” In Paper presented at the Meetings of the Midwestern Political Science Association, Chicago, IL, USA, 6 April 2006.

- Daniel A. Powers, and Yu Xie. Statistical Methods for Categorical Data Analysis, 2nd ed. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bear F. Braumoeller. “Hypothesis Testing and Multiplicative Interaction Terms.” International Organization 58 (2004): 807–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1Kunovich uses a confirmatory factor analysis to test this dichotomy across a large number of countries and finds it a useful theoretical tool for constructing identity [10].

- 2We use attitudes about policy as our dependent variable, as this is the variable that has been used in the body of literature that we are building upon (Citrin et al.; Schildkraut [7,12,13]). This is only one indicator of attitudes towards immigrants, but one of the most common in the literature.

- 3The dataset used in this paper is available upon request from the authors and will be posted on the authors’ web pages upon publication.

- 4Principle component analysis using varimax rotation. A factor loading cut-off of 0.4 was used in keeping with the previous literature (see Shildkraut [12]).

- 5The full set of supporting information is available upon request including the full text of the questions used in the analysis. The results support the dichotomy between ethnic conceptions and civic conceptions of national identity, as has been rigorously empirically tested by Reeskens and Hooghe [46]. We have set aside the indicators designed to tap incorporationism, or the notion of America as a nation of immigrants as the variables used to capture this dimension of identity in the survey are conceptually, too closely linked to the dependent variables of explaining attitudes towards immigrants. Also, previous research Schildkraut [13] has shown that these indicators do not cohere into a fourth dimension of national identity, a result confirmed in our analysis.

- 6For purposes of parsimony we do not fully explain the details here. In short, we use the score of each individual divided by the maximum possible score on that dimension. We are happy to provide additional details upon request.

- 7We generated pairwise interaction terms for all pairs of dimensions as well as a triple interaction term using all three dimensions. The results presented in this paper omit the models including most statistically insignificant interactions for purposes of parsimony and to avoid the complexities related to the interpretation of models with multiple interaction terms with shared components.

- 8Respondents are asked whether, in their opinion, the overall economy has become better, worse, or stayed the same in the past year.

- 9The UPP models in this paper were estimated using Stata v.11. The gologit2 command is used to estimate the models and produce the results appearing in our tables [51].

- 10We tested models that included all possible pairwise interactions between dimensions as well as models that incorporated a triple interaction term and found that only the ethnocultural-civic/political interaction was significant. We also tested the relationship between race and the other dimensions and found that only the white-ethnocultural interaction was significant. Complete results are available upon request.

- 11See note 12 above.

- 12The coefficients for interaction term components are not interpretable in these tables in the normal way in tables such as these. This is because the coefficient describes the impact of the variable when the other variable in the interaction term is at zero. In the case of Model 2 and 4, where a large increase in the size of the coefficient is observed, it is due to the fact that there is no zero value for the other index score. The coefficients for the Ethnocultural and Civic/Political dimensions increase because they describe a non-existent world in which the respondent has absolutely no commitment to the other index score in the interaction. The coefficients look strange because they describe an outcome that does not actually occur. Note that the index scores in Model 3, where the interaction term between the indexes is omitted, does not jump. In Model 3, the coefficient is describing the impact of the ethnocultural dimension when the value of the dummy variable for white is at zero. This describes the impact of the ethnocultural dimension on non-whites, a circumstance that does appear in the dataset.

- 13As mentioned previously, the interaction effects for other combinations of variables were not statistically significant and most results for these models are not included. See note 12.

- 14The UPP model indicated that ethnoculturalism violated proportional odds and that the impact was different shifting from 0 to 1 than from 1 to 2. This makes the display of the conditional effects more complicated in these graphs. For parsimony and readability, this graph only displays the conditional effects for the shift from 0 to 1, not from 1 to 2. While the two lines are slightly different, they do not impact the substantive relationship. The line representing the change from 1 to 2 is thus omitted. Complete results are available on request.

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).