Abstract

Gender and sexuality norms, conscribed under cis/heteropatriarchy, have established violent and unstable social and educational climates for the millennial generation of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, agender/asexual, gender creative, and questioning youth. While strides have been made to make schools more supportive and queer inclusive, schools still struggle to include lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender*+, intersex, agender/asexual, gender creative, queer and questioning (LGBT*+IAGCQQ)-positive curricula. While extensive studies must be done on behalf of all queer youth, this work specifically focuses on how to support classroom teachers to uptake and apply a pedagogy of refusal that attends to the most vulnerabilized population of queer youth to date, those that are trans*+. A pedagogy of refusal will be explored through an evolving theory of trans*+ness, then demonstrated through a framework for classroom application, followed by recommendations for change.

Any refusal to recognize reality, for any reason whatever, has disastrous consequences. There are no evil thoughts except one: the refusal to think. Don’t ignore your own desires...Don’t sacrifice them. Examine their cause. There is a limit to how much you should have to bear.—Ayn Rand [1]

And she refused to go to that miserable place he had dragged her to so many times, to hope for a thing that was unchangeable.—Jhumpa Lahiri [2]

1. Introduction

Refusal can be a tricky word. Depending on who is using it and the intention behind its use, it can have a positive or negative impact. If we consider that its common definition is to say or show that a person is not willing to do, accept, or allow something, on one hand, some may not be pleased with the decision to be refused, while on the other, it might signal that it is brave to refuse. For instance to say, “I refuse to help you”, might signal an unwillingness and yet it might indicate an act of self-preservation or protection if the request for help is connected to something unhealthy for the individual. Bearing to light the use of the word refusal, its use in the classroom can act as a mediator for learning and be a source of ushering in a strategy to trans*+ classrooms, schools, and communities of learning.

So what does it mean to refuse? How do we refuse something? What happens when we refuse? Can refusal be taught? And, how is refusal an act of self-preservation?

Typically students who refuse to do something in, and for, school are positioned as wrong, insolent, indolent and even, sometimes, troublemakers. However, what if we were to look at that term from a different angle altogether? What if we were to look at it as pedagogical strategy that can disrupt the essentialization and reification of all binaries but specifically, gender? What if refusal were taught as a strategy that supports students to be agentive in the classroom, school, and even society, where it was understood as an expansion across literacy instruction and throughout daily interactions? What if refusal were just commonplace and did not incur negative consequences when used by students in schools? What if the phrase, “I refuse to accept that” is as viable as “I agree with that?” This is where the notion of trans*+ is critical.

Trans*+

The word trans*+ infers to cut across or go between, to go over or beyond or away from, and/or to return to spaces and/or identities. It is about a constant integration of new ideas and concepts and new knowledges. Trans*+ is comprised of multitudes, a moving away or a refusal to accept essentialized constructions of spaces, binaries, ideas, genders, bodies, or identities, etc.

I conceive that trans*+ as a noun, prefix, verb or adjective, is part of the family of the ever-expanding vernacular to identify a non-cisgender person. As transgender is derived from the Greek word meaning “across from” or “on the other side of”, many consider trans*+ with the asterisk and with the plus sign to reference a continuum of evolving self-identifications and a useful umbrella term that pushes or signifies identity categories. It has also been argued that trans*+ is a reification of gender identity categories [3,4] yet other studies show that it about a life that is ever-changing, moving forward, refuting to be caught in any binary [5,6,7]. While some activists draw on the use of trans (without the asterisk and/or the plus sign), which is most often applied to trans men/women, the asterisk with the plus sign more broadly references ever-evolving non-cisgender gender identities, which are identified as, but certainly not limited to, (a)gender, cross-dresser, bigender, genderfluid, gender**k, genderless, genderqueer, non-binary, non-gender, third gender, trans man, trans woman, transgender, transsexual, and two-spirit. How the term trans*+ continues to take form will evolve as identities and theories morph in indeterminate ways.

The path to learning how refusal can be spatialized as an expansive tool for learning requires situating it within reasons it matters. Refusal emerges out of harrowing statistics incurred by trans*+ and gender-creative youth, is a remedy to stop gender-based violence, and a way to preserve the dignity of students who do not fall into reified gender identities.

2. Results

To refuse has so many more consequences than submitting.—Gillian Flynn [8]

Why Refusal Matters

Gender and sexuality norms, conscribed under cisnormativity and heteropatriarchy, have established violent and unstable social and educational climates for the millennial generation of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender*+, intersex, agender/asexual, gender creative, queer, and questioning youth (LGBT*+IAGCQQ) [9,10,11]. While strides have been made to make schools more supportive and queer inclusive [12,13], schools still struggle with inclusion of LGBT*+IAGCQQ-positive curricula. While extensive studies must be done on behalf of all queer youth, this work specifically focuses on the most vulnerabilized (i.e., made vulnerable by the educational system when not honored or attended to) population of queer youth to date, those that are trans*+.

Trans*+ and gender-creative youth are vulnerabilzed by school climates that fail to integrate curriculum, discussions, or draw upon inclusive pedagogical strategies which speak to these identities. When school climates support and privilege the normalization of heterosexist, cisgender, Eurocentric, unidimensional (i.e., non-intersectional), or gender-normative beliefs—even unconsciously—it forces students who fall outside of those dominant identifiers to focus on simple survival rather than on success and fulfillment in school [10,11]. As they strive and yearn to be positively recognized by peers, teachers, and family members, they experience macroaggressions—the systemic reinforcement of microaggressions—and are forced to placate others by representing themselves in incomplete or false ways that they believe will be seen as socially acceptable in order to survive a school day. Such false fronts or defensive strategies are emotionally and cognitively exhausting and difficult [11], otherwise known as emotional labor [14,15,16]; trans*+ and gender creative youth are thereby positioned by the school system to sustain a learned or detached tolerance to buffer the self against the countless microaggressions experienced throughout a typical school day.

When schools do not include texts, films, histories, images, events or speakers, media, music, art, policy (e.g., Common Core standards, anti-bullying, codes of conduct, athletic inclusion), or openly enumerate identities in discourse, the classroom or the school writ-large, or honor body-self care with “all gender” or “gender-inclusive bathrooms”, locker rooms, etc., that speak to their identities, or misrecognizes them altogether, such students experience a constructed or produced identity erasure [17], and can struggle with a positive self image or sense of worth. Such a recognition gap [17] condones an anxiety that produces gender-based ignorance that can lead to gender-based violence. In fact, all students suffer in this wake because missed opportunities prevent understanding, growth, and humanization to recognize their trans*+ and gender-creative peers.

As a result of such erasure, or lack of recognition, and a failure to identify expanding nuances of gender or (a)gender, trans*+ and gender-creative youth incur the highest rates amongst their peers of bullying, harassment, truancy, dropping out, substance abuse, mental health issues [11,13] and suicidal ideation [18]. School systems that do not affirm differential bodied realities become co-conspirators in limiting and narrowing current understandings of gender. Such deleterious realities beget a deeper and more systemic issue that unearths how underprepared teachers, schools, and districts are to mediate learning that affirms and creates and then sustains classrooms of recognition and school spaces for all [17,19,20].

People are in search of positive recognition because it validates their humanity [17]. When one is misrecognized it subverts the possibility to be made credible, legible, or to be read and/or truly understood [21]. To that aim, and because many tropes about trans*+ and gender creative youth focus on their suffering and misrecognition, this project hopes to advance a different narrative that calls for positive recognition. Schools can be disrupter and mediator to support trans*+ and gender creative youth in their recognition and instill a positive sense of self worth. Such an affirmed sense of self can then spatialize throughout the school and their lives. Refusal as a pedagogical strategy can disrupt these processes whereby spatialization has potential to change mindsets and, thereby, be sustained across contexts.

3. Discussion

You are already that which you want to be, and your refusal to believe it is the only reason you do not see it.—Neville Goddard [22]

3.1. Conceptualizing and Situating Trans*+ Spaces

3.1.1. Spaces

In recent research the term fourthspace [23] was coined to represent an agentive-concept based upon the groundbreaking work of the critical geographer Edward Soja who translated Henri LeFebvre’s work on thirdspace. Unlike Soja’s [24], first (real and concrete space), second (imagined space), and even thirdspace (lived space where the real and imagined come together), fourthspace is an interzone, or a socially-produced vertical space of interconnectivity between student and teacher and teacher and world. This space is located within the human psyche, a space of dormant agency, and can be enacted or triggered by experiences in classroom settings. Fourthspace is a space for agency (e.g., Zen and homeostasis) that rises above a whole society in which a deficient educational system and corporatized politics render teachers devoid of agency [25], and opens up for a teacher a hybridization of infinite terrain, of past, present, and future renderings. Through a fourthspace enactment, a teacher is imaginatively transported “into” a spacetime structuration—consider a double helix—that is only maintained and sustained by the teacher alone—sort of an attic or private/privatized dwelling, if you will, where in that space a teacher can eschew and traverse conventional models of expectations and consider possibilities for radicalization and even transformation for self and student alike before responding in the few seconds that is commonly known as “wait time” or “critical check-in out/times” [23]. It might otherwise be considered as a critical pause wherein an emotional, corporeal, and cognitive shift can occur and unifies for teachers, what Spinoza [26] called the body/mind dualism, that is often forcibly separated by and in first space. Produced spaces therefore co-exist in simultaneity, are unpredictable, non-static and in constant motion, flexible, sociospatial (i.e., embedded and can cut across and unite/connect contexts/society/ies), and temporal.

3.1.2. Body/Identity in a Trans*+ Space

When we consider a body in a trans*+ space, the body is a confluence or mash-up where a self can be made and remade, always in perpetual construction and deconstruction. Such shapeshifting demonstrates an agency to (re)create/invent/draw/write the self into identity(ies) that the individual can recognize, and be recognized by and within. When affirmed/recognized the embodiment becomes empowered as agentive. Agentive bodies, thereby, with an affirmed and recognizable sense of self, can disrupt and rupture oppressive narratives, opinions, beliefs, and environments [27,28]. Such a recast body as it moves into new spaces, whether cis or trans*+, can shift histories and pose challenges that informs new knowledge, awareness, and understanding.

3.1.3. (A)gender Self-Determination

As a body becomes agentive, it takes on (a)gender self-determination [29]. The lower case (a) in front of gender infers that gender does not have to exist (can be refused); it can exist, can shift over time and space, and in multitudes. What this means is that the body refuses the imposition to be externally controlled, defined, or regulated, has the right to make choices to self-identify in a way that authenticates one’s self-expression and self-acceptance. This body can unsettle constructed knowledge and generate new possibilities of legibility. In other words, bodies can generate and invent new knowledges or, as Butler suggests, gives, “rise to language and that language carries bodily aims, and performs bodily deeds that are not always understood by those who use language to accomplish certain conscious aims” ([3], p. 199). About a body in a trans*+ space, Foucault [30] might suggest that the self constitutes itself in discourse with the assistance of another’s presence and speech. Therefore, when teachers mediate literacy by drawing on a pedagogy of refusal that supports students to be recognized by self and other, they mediate (a)gender self-determination. When a person is (a)gender self-determined a sociospatialization (a movement of body into and across various spaces) can be realized.

3.2. Theory of Trans*+ness

In building a “space” for a theory of trans*+ness, spatiality and hybridity theories [27,31,32]; geospatial theories [31,33,34,35]; and social positioning theories [3,30,36,37,38] undergird its foundation. Arising from this plan then, trans*+ as a theoretical concept connects these studies and suggests that students have agency in how they invite in, embody, and can be recognized by the self and other as they perform multitudinous identities that can be perpetually reinvented. It also recognizes that histories have spatial dimensions that are normalized with inequities hidden in bodies whereby bodies becomes contested sites that experience social injustice temporally and spatially [33,34,35,39]. Adding to this, refusal as pedagogy for learning, literacy can move back and forth, between, over, beyond, away from, into, returned to, and be fragmented. As students come to understand and recognize these possibilities and practice its uptake encumbered by a pedagogy of refusal concomitant with their teachers, otherwise known as two-way pedagogies [40,41], their bodied communications are made legible and they become legible to others. Thought of this way, their bodies/minds become emerging forms of and for understanding and teaching. Therefore, this theory of trans*+ness suggests that for new knowledges to emerge, classrooms must be thought of and taught rhizomatically, or as a networked space where relationships intersect, are concentric, do not intersect, can be parallel, nonparallel, perpendicular, obtuse, and fragmented [27]. Taken together, a theory of trans*+ness becomes a critical consciousness about how we read and are read by the world [42] and a refusal for essentializations.

A Pedagogy of Refusal

When an individual is protesting society’s refusal to acknowledge his dignity as a human being, his very act of protest confers dignity on him.—Bayard Rustin [43]

“It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity,” declared W.E.B. Du Bois in 1903 [44]. Little did he know the truth those words would still carry today. In The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois called the world’s attention to the struggle for Black recognition and validation in The United States. He describes this as a double-consciousness, that sense of simultaneously holding up two images of the self, the internal and the external—while always trying to compose and reconcile one’s identity. He was indignantly concerned with how the disintegration of the two generates internal strife and confusion about a positive sense of self-worth.

Similar to what Du Bois named as internal strife for Black recognition, for youth who live outside of the gender binary and challenge traditionally entrenched forms of gender expression, they too experience a double-consciousness. As a way to disrupt and remedy the deleterious impact, a pedagogy of refusal acts as an intervention. Refusal can thereby support all students to develop the embedded awareness that they are entitled to (a)gender self-determination, and to be autonomous beings. Teachers who ascribe to a pedagogy of refusal have great potential to usher in indeterminate and critical change.

Refusal as a mediator for learning can be thought of as a strategy to push back on essentializations. It is a strategy that teachers, and through practice vis-à-vis fourthspace, can take up to support their students in developing ever-changing forms of recognition undergirded by the unknown and the unpredictable. Its spatialization seeks to inspire a school climate that advances and graduates self-determined youth whose bodies/minds become spatially agentive [25]. Through embodiment, refusal can shift deeply entrenched binary understandings by deepening human awareness demonstrating the complexities of (a)gender identity.

4. Methods and Materials

True ignorance is not the absence of knowledge, but the refusal to acquire it.—Karl Popper [45]

4.1. How to Refuse

A way into the practice of refusal is mediated by a Queer Literacy Framework (QLF, Table 1). The QLF is comprised of ten principles with ten subsequent commitments for educators to queer literacy practices from pre-K-12th grade classrooms. The framework is underscored by the notion that our lives have been structured through an inheritance of a political, gendered, economic, social, religious, and linguistic system we never made and with indissoluble ties to cis/heteropatriarchy. This is not to suggest that we should do away with (a)gender categories altogether, but that we pivot into an expansive and open-ended paradigm that refuses to close itself or be narrowly defined, and which strives to shift and expand views that can account for a continuum of evolving (a)gender identities and differential bodied realities. In this trans*+ space, and the yet to be defined, a QLF can shift dated norms that operationalize our lives.

Table 1.

A queer literacy framework promoting (a)gender and self-determination and justice. Modified but originally printed [29] (Copyright 2015 by the National Council of Teachers of English. Reprinted with permission).

The framework is intended to be an autonomous, ongoing, non-hierarchical tool within a teaching repertoire; it is not something someone does once and moves away from. Rather, the principles and commitments should work alongside other tools and perspectives within a teacher’s disposition and curriculum. An intention of the framework is that it can be applied and taken up across multiple grades, genres and disciplines within literacy acquisition, and its sociospatialization can expand the spaces we all inhabit. As mediators for learning, students and teachers learn together about self- and otherly-identification. Moving into the framework, axioms underscore the beliefs that guide the principles and commitments (see Box 1). Discussing these axioms and unpacking its language with students, can cultivate a deeper awareness about how some people embody prejudice. Building from these axioms then, teachers can practice this framework and generate assignments based on various principle(s) (see [29,46] for examples).

Box 1. Axioms for a pedagogy of refusal.

- ➢

- We live in a time we never made, gender norms predate our existence;

- ➢

- Non-gender and sexual “differences” have been around forever but norms operate to pathologize and delegitimize them;

- ➢

- Children’s self-determination is taken away early when gender is inscribed onto them. Their bodies/minds become unknowing participants in a roulette of gender norms;

- ➢

- Children have rights to their own (a)gender legibility;

- ➢

- Binary views on gender are potentially damaging;

- ➢

- Gender must be dislodged/unhinged from sexuality;

- ➢

- Humans have agency;

- ➢

- We must move away from pathologizing beliefs that police humanity;

- ➢

- Humans deserve positive recognition and acknowledgment for who they are;

- ➢

- We are all entitled to the same basic human rights; and,

- ➢

- Life should be livable for all.

4.2. Examples of a Pedagogy of Refusal Drawing on the QLF

There are infinite possibilities for taking up a Pedagogy of Refusal drawing on the QLF. In classroom practice, for any subject, teachers can be creative and imaginative about how to integrate various principles into and across their curriculum. As teachers take up this work, they should be mindful about their school policies, mores, and potential obstacles. Sadly, we still live in a time where teachers have to be cautious about what they still integrate especially in states which have No Promo Homo Laws (states that forbid a positive representation of LGBT topics and/or any discussion at all) and in various conservative communities. Below I highlight one example from each major school level though more examples are demonstrated in Teaching, Affirming and Recognizing Trans and Gender Creative Youth: A Queer Literacy Framework [17].

4.2.1. Pre-School

In a pre-school classroom teachers might consider using picture books, art, animals, drafting and writing stories, and using manipulatives to integrate various principles. For instance, using Principle 10, Believes that students who identify on a continuum of gender identities deserve to learn in environments free of bullying and harassment, a teacher can discuss what bullying is, can be, and could be. While some of the ideas, concepts, and vocabulary terms are rather dense, teachers would need to reflect on how to simplify the concepts.

Teachers and students can co-create classroom norms that can help mediate bullying behavior. The class could read a story such as I am Jazz [47], an illustrated autobiography about a gender-creative girl named Jazz. The class can reflect on how Jazz is made fun of, teased, marginalized, and bullied at school. They can look at institutional responses such as who stood up for Jazz and who did not, and what impact that had on her and her family. They might chart her story and look for these examples and talk about how they or others feel who might experience bullying. The unit could conclude with what the class can do for the school that addresses bullying behavior. Other examples that address Principle 10 are below in Box 2.

Box 2. Examples of Principle 10.

Pre-Reading Strategies

- Ask students if they have ever experienced or currently experience microaggressions or bullying because of their actual or perceived (a)gender or (a)sexuality. Ask how did/does the bullying impact them? What were/are the psycho, social, emotional, or physical consequences? Has it stopped? What made it stop?

- Ask students if they have ever bullied or are currently bullying someone because of their actual or perceived (a)gender or (a)sexuality. Ask how do they think it is impacting others? Ask them to consider the psycho, social, emotional, physical or possible long-term consequences? Did they stop? If not, ask them if they want or need support to stop.

- Ask students if they know someone who has ever experienced or currently experiences microaggressions or bullying because of their actual or perceived (a)gender or (a)sexuality. Ask how did/is the bullying impact the person? What were/are psycho, social, emotional, physical or possible long-term consequences? Ask if they intervened. Has it stopped? What made it stop?

- Ask students if there is a GSA, anti-bullying program, anti-bullying curriculum, statements against bullying in the code of conduct (are identities enumerated? Who is included? Excluded in the policy), or a peer-support network in the school. Ask what impact do those elements seem to have on the school environment?

- Ask students if individual classrooms or the school feels safe. What stances have teachers or the school taken to generate a safe and inclusive environment?

- If school feels unsafe what could help make it safe? How might they get involved?

- Ask, what they wish they could tell a teacher, administrator, or other school personnel about themselves or other students who feel unsafe?

- Ask students if their local community has outreach and organizations that affirm gender and sexual minorities (GSM). Are they aware of any local or state policies that support GSM?

- Ask students if they know of any local, state, or national policies that affirm GSM. If so, what are they and what kind of impact do they have on people?

- Ask students to consider which authors have addressed bullying and harassment related to GSM. What have they learned from those texts?

Comprehension Strategies

- Ask students which characters experienced or currently experience microaggressions or bullying because of their actual or perceived (a)gender or (a)sexuality. Ask how did/is the bullying impact them? What were/are the psycho, social, emotional, physical or possible long-term consequences? Has it stopped? What made it stop?

- Ask students which characters ever bullied or are currently bullying someone because of actual or perceived (a)gender or (a)sexuality. Ask, how does the character think it is impacting others or even themselves? Ask them to consider the psycho, social, emotional, physical or possible long-term consequences of the bullying behavior? Has it stopped? How did it stop?

- Ask students what role the character plays in relation to someone who has ever experienced or currently experiences microaggressions or bullying because of actual or perceived (a)gender or (a)sexuality. Ask how did/does the bullying impact the character or the victim? What were/are the psycho, social, emotional, physical or possible long-term consequences on each? Ask, if they intervened. Has it stopped? What made it stop?

- Ask students if the school setting in the text has a GSA, anti-bullying program, anti-bullying curriculum, statements against bullying in the code of conduct (Are identities enumerated? Who is included? Excluded?), or a peer-support network in the school. Ask, what impact do those elements seem to have on the school environment?

- Ask students if characters in the text think school or individual classroom feels safe. What textual evidence supports their point of view? What stances have teachers or the school taken to generate a safe and inclusive environment?

- If school feels unsafe for characters, ask students what could help make it safe? What kind of support could your students offer or say to characters in text?

- Ask, do characters express an inward or outward desire to tell a teacher, administrator, or other school personnel about students or themselves who feel unsafe?

- Ask students if the text describes local community resources or organizations that affirm GSM. Are characters aware of any local or state policies that support GSM?

- Ask students if the author describes any local, state, or national policies that affirm GSM. If so, what are they and how are they woven into the plot?

- Ask students in what ways these characters acted as change agents in their lived worlds. Who, what, and/or how were they impacted?

Cultural Connections

- Ask students to make connections and draw inferences between characters and artists, musicians, athletes, media personalities, religious figures, politicians, friends, or family, etc., who have experienced bullying or bullied others. What are their stories? What have they experienced? How were/are they treated? How did they treat others? How are their lives today? Were amends made? If so, how? What have you learned about the ways they perform their identities? What can you now teach others about anti-bullying?

4.2.2. Elementary

In an elementary school classroom, and depending on which grade level, if someone were teaching a third or fourth grade class, and drawing on Principle 1, Understands gender as a construct which has and continues to be impacted by intersecting factors (e.g., social, historical, material, cultural, economic, religious), a teacher can invite dialogue about the importance of self and wanting others to see and recognize them while developing empathy and appreciation for others (see Box 3). To do this work, teachers can apply these questions to texts, TV, cartoons, posters, music, art, social networking, etc. As for any grade level, terms and ideas should be broken down and unpacked significantly. Below is a list of strategies that provide multiple pathways to engage with Principle 1. Again, some of these questions may not be appropriate for certain schools so teachers may have to avoid certain topics.

Box 3. Examples of pathways for Principle 1.

Pre-Reading Strategies: Explore characteristics of gender markers

- Ask students where notions of gender arise. Ask them how such notions are reinforced. Ask, do people have to “be” or “have a gender”.

- Ask students what ideas, concepts, behaviors, mannerisms, activities, dress, feelings, occupations, seem to be identified with gender. Ask them for examples in society where gender seems fluid and non-descript. Ask for examples where people seem (a)gender or gender flexible.

- Ask students what makes gender matter?

- Ask, what happens to people who are gender flexible or who seem to behave in a gender that is different than their assigned sex.

- Ask students how gender and sex are different.

- Ask students to consider why and which authors try to reinforce binary gender behaviors and performances. If so, which authors have they observed enacting this? What have they learned from those texts?

Comprehension Strategies

- Ask, how are characters in the text treated because of gender?

- Ask, are there any characters who seem to transcend gender markers?

- Ask, for the characters in the text, are there any personal, social, familial, cultural, economic, linguistic, political, or religious consequences for transcending gender markers?

- What sort of support (if any) is given to elements or characters who question the gender binary? What happens to those elements/characters?

- Ask, how does the author resolve any conflict incurred by characters that transcend gender orientation markers?

- Ask, for any characters, how does the author treat healing? Remorse? Redemption? The future?

- Ask students in what ways these self-identified characters acted as change agents in their lived worlds. Who, what, and/or how were they impacted?

Cultural Connections

- Ask students to make connections between characters and artists, musicians, athletes, media personalities, religious figures, politicians, friends, or family, etc., who do not ascribe to expected gender markers. What are their stories? How were/are they treated? What have they experienced? How are their lives today? What have you learned about gender markers from those individuals? What can you now teach others about those who do not ascribe to expected gender markers?

4.2.3. Middle School

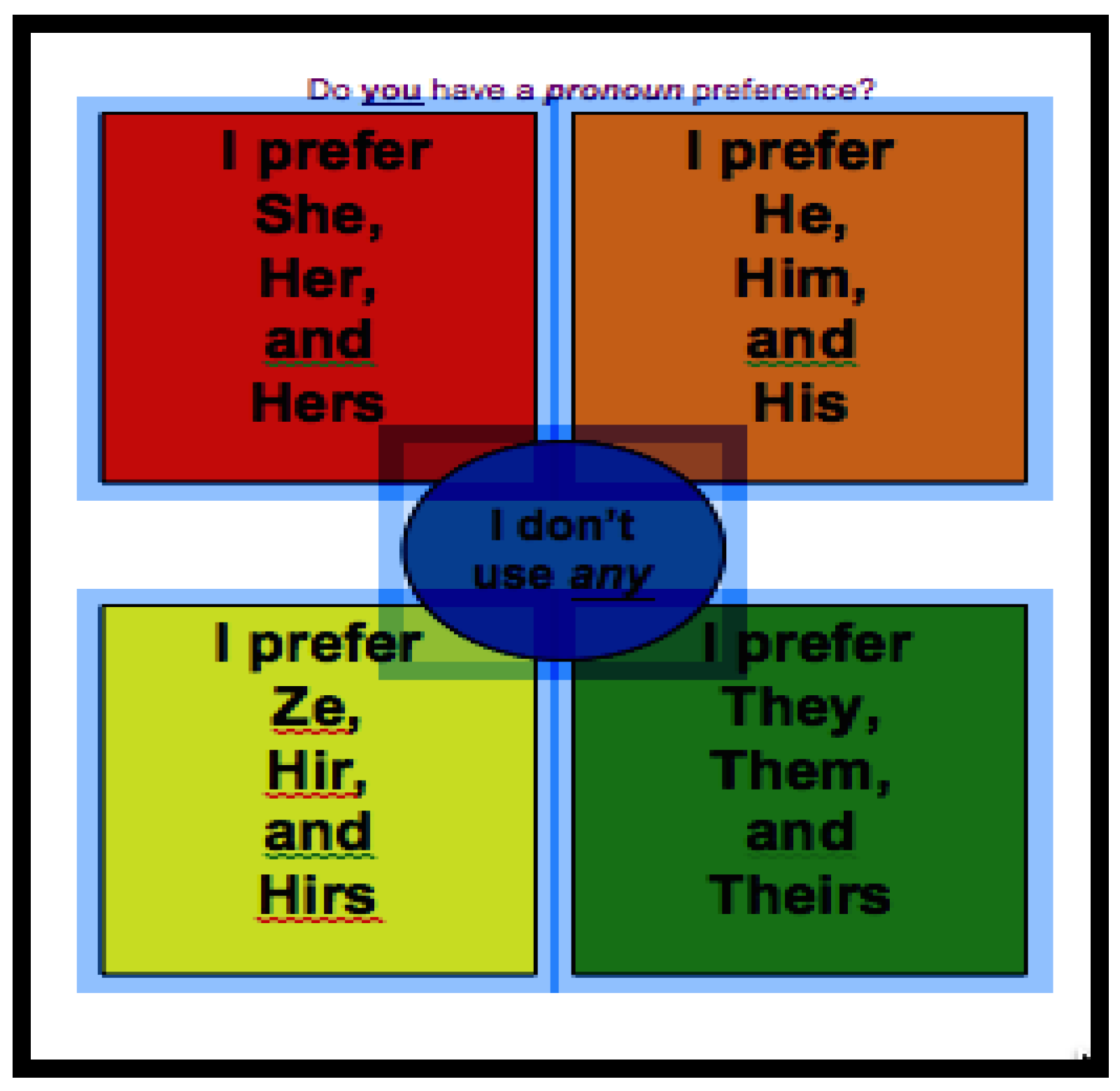

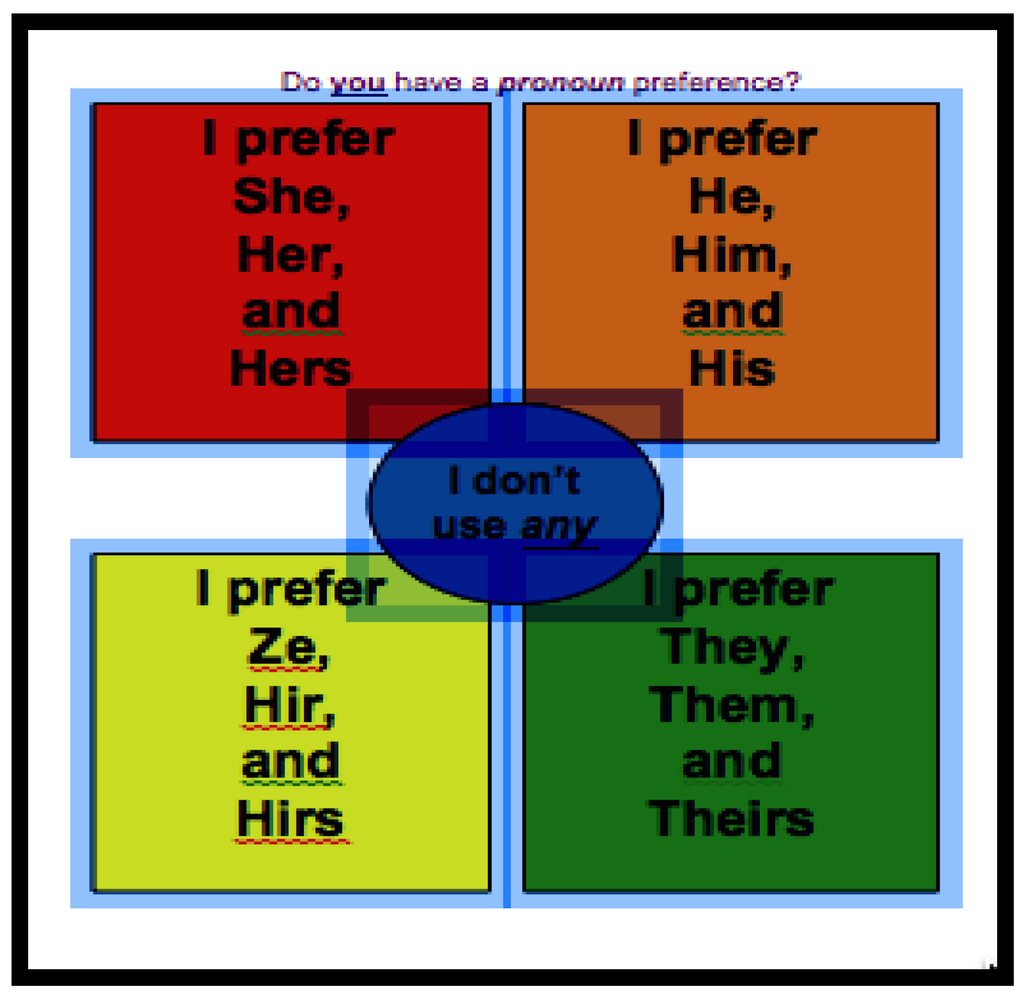

If someone were teaching in a middle school classroom they might choose to draw on Principle 5, Opens up spaces for students to self-define with chosen (a)genders, (a)pronouns, or names. At the beginning of the school year, teachers could hand out a slip of paper, that I call “Get to Know Me”, which allows students to privately reveal their chosen and/or preferred name, (a)pronouns (i.e., pronouns or absence of), and (a)gender, and, with an option to note if they want of these categories publically acknowledged (see Box 4). For the student who does not want others to know about particular identities, but is comfortable sharing that part of the self with the teacher, the teacher can respond on assignments with comments that recognize the student’s true (a)gender, preferred name, and (a)pronoun. With the initial slip of paper, the teacher sends a clear message to the class about the importance of affirmation and legibility and, thereby, recognition. In addition, to this strategy, the teacher can post placards in the classroom that affirm gender identity, and inclusivity (see Figure 1 and Figure 2) and make (a)gender recognition part of the classroom norms. The following list (see Box 5) provides additional pathways to engage with Principle 5. Teachers might consider using media, TV, art, music, graffiti, billboards, magazines, books, plays, equations, observations, sports, formulas, or any other medium that motivates learning and engagement.

Figure 1.

(A)pronoun poster.

Figure 2.

Inclusive Space poster.

Box 4. Get to Know Me.

Names—(please fill in the gaps in the sentences below—using the following prompts)

My assigned name is ___________________ and my chosen or preferred name (leave blank if they are the same) is__________________________. My assigned gender is __________ but my CURRENT, chosen or preferred (a)gender (leave blank if they are the same) is _________________. The pronouns people use when referring to me include ________________ but my CURRENT, chosen or preferred (a)pronoun is/are _______________. In class I prefer you to use (circle one) assigned or chosen/preferred (a)pronouns when referring to me, but on my assignments you can use (circle one) assigned or chosen/preferred (a)pronouns.

Box 5. Examples of pathways for Principle 5.

Pre-Reading Strategies

- Ask students if they like their names. Why or why not? Ask them if they have a right to change their name or prefer to be called by a different name.

- Ask students which pronouns the English language has for gender. Ask them if they like those. If not, what other suggestions do they have. Ask, have they ever considered that some people don’t feel certain pronouns fit their identities.

- Ask students if people have a right to refuse to be pronouned. Are there any “real” rules that keep a person from selecting pronouns that fit more appropriately. Are there any “real” rules that keep a person from refuting to be identified by a pronoun?

- Ask students what it feels like to have something private about themselves revealed.

- Ask students why respecting privacy is important.

- Ask students why some people might be uncomfortable sharing aspects of their (a)gender or with others.

- Ask students in what ways teachers can demonstrate respect for students’ privacy related to (a)gender and (a)pronoun choice (refusal to be pronouned).

- Ask students in what ways schools, doctors, dentists, coaches, etc., can demonstrate respect for students’ privacy related to (a)gender and (a)pronoun choice.

- Ask students to consider which authors explore issues of chosen (a)gender (a)pronouns and naming. What have they learned from those texts?

Comprehension Strategies

- Ask students if textual characters revealed private information to anyone about (a)gender, chosen names or (a) pronouns.

- Ask students if any of the textual characters had private information related to (a)gender publically revealed.

- Ask students how the textual characters responded to the breach of information.

- Ask students if there were any consequences or redress about the breach.

- Ask students why the textual characters were uncomfortable sharing aspects of their (a)gender with others.

- Ask students in what ways teachers, parents, peers, family, social circles, others demonstrated respect for textual characters characters’ privacy related to (a)gender and (a)pronoun choice (refusal to be pronouned).

- Ask students in what ways the textual characters who revealed their (a)gender, and chosen name or (a)pronoun choice felt normalized in school, home, with family, peers, etc.

- Ask students in what ways these self-defined characters acted as change agents in their lived worlds. Who, what, and/or how were they impacted?

Cultural Connections

- Ask students to make connections and draw inferences between textual characters and artists, musicians, athletes, media personalities, religious figures, politicians, friends, or family, etc., who have had private aspects of their (a)gender revealed publically. What are their stories? What have they experienced? How were/are they treated? Was there an apology? How did they respond? How are their lives today? What have you learned about the ways they perform their identities? What can you now teach others about respecting one’s right to self disclose?

4.2.4. High School

In a high school classroom, teachers are likely to have more flexibility about integrating various principles into their curriculum. Below are numerous examples, drawing on multiple curricular media for possible pathways about creating lessons that tap into Principle 6, Engages in ongoing critique of how gender norms are reinforced in literature, media, technology, art, history, science, math, and so on (see Box 6).

Box 6. Examples of Principle 6.

Pre-Reading Strategies

- Ask students to log how gender norms are reinforced in a chosen movie, talk show, TV show. How is gender policed?

- Ask students to log how gender norms are reinforced in school (other classes, school policies, messages, posters, sports, etc.,). How are gender norms socially policed?

- Ask students to log how gender norms are reinforced in different disciplines and genres/sub genres within technology, art, history, radio, music, literature, science, math, sports, policy, etc. How are gender norms socially policed?

- Ask students to provide examples about where in these disciplines there is push back against gender norms. Ask what have they learned from the push back?

- Ask students to consider which authors explore social policing and reinforcement of (a)gender

- What have they learned from those texts?

Comprehension Strategies

- Ask students to log how gender norms are reinforced in texts across different aspects of characters’ lives. How are gender norms socially policed in the text?

- What messages do the characters receive? How are they interrupted and disrupted?

- Ask students to provide examples about who pushes back against these gender norms. Ask what have they learned from the push back?

- Ask how was gender interrupted? What impact does this have on the characters or social environment. How do people come to read each other differently?

- Ask students in what ways these characters acted as change agents in their lived worlds. Who, what, and/or how were they impacted?

Cultural Connections

- Ask students to make connections and draw inferences between textual characters and artists, musicians, athletes, media personalities, religious figures, politicians, friends, or family, and in any academic discipline, etc., who have pushed back against gender norms and embrace (a)gender presentation. What are their stories? What have they experienced? How were/are they treated? How are their lives today? What have you learned about the ways they perform their identities? What can you now teach others about challenging gender norms and embracing (a)gender presentations?

4.2.5. Post Secondary

In a university classroom of pre-service teacher education students for example, students can participate in a number of gender, cisgender, and heteronormative audits in order to determine how these identities are reinforced in any given twenty-four hours. The purpose of these activities are to draw attention to the aggregate, and often unconscious reinforcement, of beliefs about identities across a week, a month, a year, a lifetime, etc., and how such messages reinforce dominant perceptions of identities. During this time, students can be asked to chart their observations from when they wake up until the next day, what they see, what was said, and who was reinforcing the identity. They can bring in their findings and fill in data on butcher paper. They can do a gallery walk and observe all of the comments from those twenty-four hours. Such a panorama will reveal how people have been constructed to take on gender roles, norms, and stereotypes in direct and indirect ways.

In this order, students can do the audits over two weeks: gender, cisgender, heteronormativity (see Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 below). During each audit, the QLF can be used to unpack the essentialized constructions. Students can look across which principles surface for each of them. They can then create lesson plans to teach each other and the students they work with in their placements—if so permitted—about how to push back and refuse to accept socially- or materially-produced identity constructions.

Table 2.

Audit of Gender Awareness.

Table 3.

Audit of Cisgender Awareness.

Table 4.

Audit of Heteronormative Awareness.

5. Conclusions: Refusal as a Means to Self-Preservation

One of the truest tests of integrity is its blunt refusal to be compromised.—Chinua Achebe [48]

5.1. Recommendations for Change

Change is possible: spaces and mindsets can become trans*+ed. As elements shift, the trans*+ gender creative body becomes validated, legible, and recognized by the spaces they inhabit. The double-consciousness then, or psychic split that many trans*+ and gender-creative youth experience, can be alleviated as schools intervene, disrupt, and affirm the trans*+ body by trans*+ing spaces. As teachers have opportunities to more readily understand trans*, the inhabitation of fourthspace becomes part and parcel to the teaching practice. A challenge we face together in the teaching profession then, is the sustainability of such change.

Future research must—not could or should, but must—take up how to trans*+ schooling experiences for all youth across all identities and intersectionalities. Districts and schools must commit to such efforts in order for change to become sustainable across pre-K-12th grade curriculum. To these aims, it is recommended that,

- ✓

- Researchers must address ongoing gaps in teacher education and work closely to continue to deepen and develop the efficacy of a pedagogy of refusal practiced through strategies that affirm and recognize the intersectional realities facing trans*+and gender creative youth;

- ✓

- Preservice teacher education must introduce (a)gender identity topics in early childhood education and throughout elementary, middle, and secondary coursework, and across disciplinary programs. Programs should decide in which courses such uptake would fit best;

- ✓

- Teacher educators must work closely with school districts to develop professional development models that can support curriculum specialists and teachers in their ongoing awareness about how to meet the needs of trans*+ and gender-creative youth and how to trans*+ classrooms and schools;

- ✓

- Since no district faces identical issues nor has identical student bodies, district curriculum specialists must work alongside classroom teachers and educate each other about the classroom and schooling experiences of their trans*+ and gender-creative youth. Collectively they can develop curriculum that develops (internal and external) safety, is inclusive, and affirming, and generates both recognizability and visibility to self and other;

- ✓

- Districts and schools must work closely with community organizations that address (a)gender and gender violence (e.g., rape crisis centers, LGBT or gender identity non-profits, doctors, mental health and health care practitioners), to develop a deeper understanding of the issues facing trans*+ and gender-creative youth;

- ✓

- Districts and schools must work alongside families so as to learn from, and with, their experiences and to develop support groups;

- ✓

- Districts and schools must work to change and update district and school policy, codes of conduct, to enumerate bullying policies, to create safe bathrooms and locker rooms, to consider issues about participation in sports and physical education classes—typical spaces for extreme harassment, and to reflect on how to create a schooling environment that can help to foster external safety; and,

- ✓

- Teacher educators, districts, schools, community organizations, and families must caucus with legislatures to change state policy about trans*+ rights to be more inclusive of health care needs, identification changes, and bullying policies.

5.2. Post Trans*+Schooling

For a very long time everybody refuses and then almost without a pause almost everybody accepts.—Gertrude Stein [49]

The Future Is Now—The Post Trans*+

So, what might a trans*+/post-trans*+ schooling system look like, and how might that potentially change humanity? Postulating that as trans*+ becomes part of the fabric of the schooling system and woven into the mainstream of society, we enter into a post trans*+ space. A post trans*+ space, though indeterminate, would demonstrate how contexts have become sustainable to hold and care for the commonplace expansion of the trans*+ and gender-creative body. In these myriad spaces (e.g., schools, jobs, families, etc.) trans*+ and gender creativity would no longer incur microaggressions nor marginalization, but for those who embody these identities they would experience the same dignities entitled to any other human. In this post trans*+ space, the possibility for the unknown and for new knowledges to continue to emerge would become integrated. In post-trans*+ contexts therefore, while people will always see difference, the prior systemic misrecognition dysphoria of trans*+ and gender creativity, collapses.

If, indeed, this post-trans*+ space were realized, a space where trans*+ness blends but does not blend in, and as trans*+ and gender-creative youth, and all people for that matter, experience these expanding contexts, humanity might not only see more trans*+ gentleness, they might see and experience more trans*+ and gender-creative justice. In the wake of such justice then, for schools, curriculum would include trans*+ and gender-creative narratives, books of all genres and story lines, histories, political victories, trailblazers, photos and pictures, and media icons. Students would have ample options for names, (a)pronouns, and (a)gender. There would be no fear of bullying or harassment related to bathrooms, locker rooms, and physical education classes and, most important, school would no longer be about survival, it would be about success, thriving, and fulfillment. The noise and emotional labor once tolerated finally fades away into the distance. No longer would they experience a double-consciousness or have to validated through another’s gaze. When, not if, the post trans*+ happens, mindsets will spatialize across contexts and our trans*+ and gender-creative youth coming into the world would not need nearly half a lifetime to discover their true selves—they would just be free to be themselves in a world better prepared to embrace, accept, love, and recognize them from birth.

When, and as, a pedagogy of refusal has uptake as a mediator for learning, and where once pathologizing those who refuse are now celebrated, trans*+ness has an unchartered permanence and as theory/pedagogy and curriculum alters minds, such an embodied praxis can and will trans*+form spaces. With refusal constitutive of literacy learning and literacy learning constitutive of refusal, identities become constitutive of refusal; thereby, refusal is an act of self-preservation. As compassion and mindsets are expanded and deepened, and with the development of even more resources to teach, affirm and recognize our trans*+ and gender-creative youth, (a)gender self-determination is no longer just a possibility or probability, but, a reality.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Ayn Rand. “Forber Quotes.” Available online: http://www.forbes.com/quotes/814/ (accessed on 22 July 2016).

- Jhumpa Lahiri. “Quotes About Refusal.” Available online: http://www.goodreads.com/quotes/tag/refusal (accessed on 22 July 2016).

- Judith Butler. Undoing Gender. New York: Routledge, 2004, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kristen Schilt, and Laurel Westbrook. “Doing Gender, Doing Heteronormativity Gender Normals: Transgender People, and the Social Maintenance of Heterosexuality.” Gender and Society 23 (2009): 440–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David Valentine. Imagining Transgender: An Ethnography of a Category. Durham: Duke University Press, 2007, pp. 38–39. [Google Scholar]

- Julie L. Nagoshi, and Stephan/ie Brzuzy. “Transgender Theory: Embodying Research and Practice.” Affilia 25 (2010): 431–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susan Stryker. Transgender History. Berkeley: Publishers Group West, 2008, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Gillian Flynn. “Quotes About Refuse.” Available online: http://www.goodreads.com/quotes/tag/refuse (accessed on 22 July 2016).

- Renee DePalma, and Dennis Francis. “The gendered nature of South African teachers’ discourse on sex education.” Health Education Resources 13 (2014): 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- sj Miller. “Moving an anti-bullying stance into schools: Supporting the identities of transgender and gender variant youth.” In Critical Youth Studies Reader. Edited by Shirley Steinberg and Awad Ibrahim. New York: Peter Lang, 2014, pp. 161–71. [Google Scholar]

- sj Miller, Leslie Burns, and Tara Star Johnson. Generation BULLIED 2.0: Prevention and Intervention Strategies for Our Most Vulnerable Students. New York: Peter Lang, 2013, pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- GLSEN. “States with Safe School Laws.” Available online: http://www.glsen.org/article/state-maps (accessed on 1 December 2013).

- Joe Kosciw, Emily Greytak, Elizaneth Diaz, and Mark Bartkiewicz. The 2009 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth in our Nation’s Schools. New York: GLSEN, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Arlie Hochschild. The Managed Heart: The Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983, pp. 337–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kevin Nadal, David Rivera, and Melissa Corpus. “Sexual orientation, and transgender microaggressions: Implications for mental health and counseling.” In Microaggressions and Marginality: Manifestation, Dynamics, and Impact. Edited by Derald Wng Sue. Hoboken: Wiley, 2010, pp. 217–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sonny Nordmarken. “Everyday Transgender Emotional Inequality: Microaggressions, Micropolitics, and Minority Emotional Work.” In Paper Presented at The American Sociological Association Annual Meeting, Denver, CO, USA, 17–20 August 2012.

- sj Miller. Teaching, Affirming and Recognizing Trans and Gender Creative Youth: A Queer Literacy Framework. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Michele Ybarra, Kimberly Mitchell, and Joe Kosciw. “The relation between suicidal ideation and bullying victimization in a national sample of transgender and non-transgender adolescents.” In Youth Suicide and Bullying: Challenges and Strategies for Prevention and Intervention. Edited by Peter Goldblum, Dorothy Espelage, Joyce Chu and Bruce Bognar. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014, pp. 134–47. [Google Scholar]

- Todd Jennings. “Is the mere mention enough? Representation across five different venues of educator preparation.” In Handbook of Gender and Sexualities in Education: A Reader. Edited by Elizabeth Meyer and Dennis Carlson. New York: Peter Lang, 2014, pp. 400–12. [Google Scholar]

- Teresa Quinn, and Erica Meiners. “Teacher education, struggles for social justice, and the historical erasure of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer lives.” In Studying Diversity in Teacher Education. Edited by Arnetha Ball and Cynthia Tyson. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2011, pp. 135–51. [Google Scholar]

- Melissa V. Harris-Perry. Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Neville Goddard. “Quotes About Refusal.” Available online: http://www.goodreads.com/quotes/tag/refusal (accessed on 22 July 2016).

- sj Miller. “Fourthspace—Revisiting social justice in teacher education.” In Narratives of Social Justice Teaching: How English Teachers Negotiate Theory and Practice Between Preservice and Inservice Spaces. Edited by sj Miller, Laura Beliveau, Todd DeStigter, David Kirkland and Pamela Rice. New York: Peter Lang, 2008, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Edward W. Soja. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places. Malden: Blackwell, 1996, p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Brad Baumgartner. “Towards an Ethics of Selfhood: An Essay on Fourthspace, Ontology and Critical Pedagogy.” Unpublished work. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Harold Bloom. “Review of Deciphering Spinoza, the Great Original—Book review of Betraying Spinoza. The Renegade Jew Who Gave Us Modernity.” The New York Times, 6 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- sj Miller. “English is ‘Not just about teaching semi-colons and Steinbeck’: Instantiating dispositions for socio-spatial justice in English Education.” Scholar-Practitioner Quarterly 3 (2014): 212–40. [Google Scholar]

- Doreen Massey. For Space. London: Sage Publications, 2005, pp. 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- sj Miller. “A Queer Literacy Framework Promoting (A)gender and (A)sexuality Self-Determination and Justice.” English Journal 5 (2015): 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Michel Foucault. The History of Sexuality. New York: Vintage, 1990, p. 163. [Google Scholar]

- Edward Soja. Seeking Spatial Justice. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010, pp. 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Giles Deleuze, and Felix Guittari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Jan Nespor. Tangled Up in School: Politics, Space, Bodies and Signs in the Educational Process. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick P. Slattery. Curriculum Development in the Postmodern Era. New York: Garland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick P. Slattery. “Toward an eschatological curriculum theory.” JCT: A Interdisciplinary Journal of Curriculum Studies 3 (1982): 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno Latour. “‘On Interobjectivity’ (Translated by Geoffrey Bowker).” Mind, Culture, and Activity: An International Journal 3 (1996): 228–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevin Leander, and Margaret Sheehy. Spatializing Literacy Research and Practice. New York: Peter Lang, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sarah McCarthey, and Elizabeth Moje. “Identity Matters.” Reading Research Quarterly 2 (2002): 228–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- sj Miller, and Linda Norris. Unpacking the Loaded Teacher Matrix: Negotiating Space and Time between University and Secondary English Classrooms. New York: Peter Lang, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gloria Ladson-Billings. The Dreamkeepers: Successful Teaching for African-American Students. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Carol Lee. Culture, Literacy, and Learning: Taking Bloom in the Midst of the Whirlwind. New York: Teachers College Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Paulo Freire. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Herder and Herder, 1970, p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Bayard Rustin. “Author (Bayard Rustin) Quotes.” Available online: https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/472455.Bayard_Rustin (accessed on 22 July 2016).

- William Edward Burghardt Du Bois. Souls of Black Folks. Chicago: A.C. McClurg & CO, 1903. [Google Scholar]

- Karl Popper. “Karl Popper > Quotes > Quotable Quote.” Available online: http://www.goodreads.com/quotes/624261-true-ignorance-is-not-the-absence-of-knowledge-but-the (accessed on 22 July 2016).

- sj Miller. “Reading YAL queerly: A queer literacy framework for inviting (a)gender and (a)sexuality self-determination and Justice.” In Beyond Borders: Queer Eros and Ethos (Ethics) in LGBTQ Young Adult Literature. Edited by David Carlson and Darla Linville. New York: Peter Lang, 2015, pp. 153–80. [Google Scholar]

- Jessica Herthel, and Jazz Jennings. I Am Jazz. New York: Dial Books, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chinua Achebe. “Brainy Quote.” Available online: http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/c/chinuaache381166.html (accessed on 22 July 2016).

- Getrude Stein. “Getrude Stein Quotes.” Available online: https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/9325.Gertrude_Stein (accessed on 22 July 2016).

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).