1. Introduction

The main goal of this research is to understand whether the legislative context of the country of residence could influence the psychological well-being of lesbian and gay individuals (LG); our hypothesis was investigated by comparing two groups of LG individuals living in two different European countries.

Earlier studies observed a higher incidence of mental health disorders and alcohol abuse among LG people compared to heterosexuals, in particular when considering individuals who lived in countries where legislation does not guarantee and defend their civil rights [

1,

2]. Being aware of the socially repressive and hetero-sexist environment in which LG people live seems to have an impact on their decision to fight against it, for example defending the traditional family, composed of a mother, father and their biological child, or even to mask their own sexual identity. While this may allow LG individuals to avoid direct homophobic experiences, it increases, as a consequence, the risk of developing physical, and/or psychological problems, such as drug abuse or eating disorders and sexually-transmitted diseases such as HIV or Syphilis due to unsafe sexual behaviors [

3].

This field of investigation has identified two principal and distinct risk factors which include those group-specific minority stressors and general psychological processes that are common across minority sexual orientations. Meyer [

4] postulated that members of sexual minority groups are exposed to stigma, namely, risk and stress factors connected with personal and social conditions which originate from belonging to a marginalized and stigmatized group.

According to Hatzenbuehler [

5], this stigma-related stress generates higher levels of general emotion dysregulation, social/interpersonal problems, and cognitive processes, increasing the risk for the onset of some kind of psychopathology. The cognitive processes affected by exposure to stigma-related stress are conceptualized as thought processes (both the content of thoughts, as well as the process of thinking) that exacerbate, maintain or prolong symptoms of depression and anxiety [

1]. One aspect of psychological health that impacts sexual minorities is the concept of internalized homophobia [

6]. This refers to a self-perception—whether conscious or not—specifically used to denote the set of feelings and negative attitudes oriented toward one’s own or others’ sexual minority status [

3].

A wide variability on internalized homophobia intensity exists among lesbian, gay men, bisexual, transsexual (LGBT) individuals. In part, differences in level of internalized homophobia seem to depend on social variables, such as the geographical location of residence, for example, the urban or rural context, social class, family convictions, namely, the family beliefs about someone being a sexual minority, and personal psychological variables, such as low self-esteem, vulnerability to environmental conditioning and adopted coping strategies [

7,

8,

9].

In general, the degree of internalized homophobia present seems to have a central role in gay men and lesbian individuals’ development and adaptation, referring particularly to the process of formation of sexual identity and the level of visibility and disclosure of one’s sexual minority status (coming out). According to Montano (2007), between the discovery of same-sex attraction and the acceptance of a LGB (lesbian-gay men-bisexual) identity as an integral part of one’s overall identity, there is a temporal time-lag.

Generally, the first steps of the LGB identity formation process are characterized by confusion and desperation, low self-esteem and poor self-acceptance. Over time LGB people tend to develop positive attitudes toward their identity, to increase their personal and social contacts with other LGB persons and thus, have an increased desire to continue coming-out [

10]. Indeed, a correlation between high levels of internalized homophobia and poor sexual identity development, low levels of self-disclosure and problematic aspects of the coming-out process has been demonstrated [

6,

10,

11]. Rowen and Malcom (2002) found higher levels of internalized homophobia were correlated with lower stages of LGB identity formation. Additionally, internalized homophobia was significantly related to lower levels of self-concept related to physical appearance, to lower level of self-esteem and emotional stability, as well as being related to higher levels of sex guilt [

11].

In this line, the connecting link between internalized homophobia and mental and physical well-being has been supported by results obtained from various studies. These have also highlighted relevant associations with the onset of mental disorders, such as substance abuse and eating disorders, with risky behavioral patterns, such as involvement in high risk sexual behavior [

4,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. A meta-analysis performed by Newcomb and Mustanski [

19] on 31 studies, which analyzed 5831 homosexual and bisexual individuals in total, also confirmed this relationship. A strong correlation between internalized homophobia and psychopathological manifestations, such as depression and anxiety, was observed.

Similar to findings involving other minority groups, in LGBT individuals, the perception of social support was found to be an important protective factor, protecting LGBT persons from stressful experiences and preventing the development of psychological diseases [

5]. The role of family support has remained undisputed, even though it may vary according to age: in fact, since adolescence, the peer group increasingly influences the identity of individual, considering in particular the amount of time that it is spent together by people of this developmental stage [

20].

A study by Mustanski, Newcomb and Garofalo [

21] underscored the extent to which peer support plays a role in promoting people’s well-being across the life course, and highlighted that the impact of social support provided by friends is even greater than the level of support given by family [

22].

Furthermore, LGBT groups and associations seem to constitute an important source of social support; the involvement in these groups has been shown to enhance positive coping strategies and to offer important skills inside of a supportive community and environmental framework allow these people to become more capable of dealing with difficulties [

23].

2. Goals of the Study

In accordance with the literature presented above, our research aimed to explore the levels of internalized homophobia, anxiety and depression among two groups of gay men and lesbian individuals living in two different European countries with different legislations and civil rights extended to LGBT individuals: Italy and Belgium. The choice to recruit subjects in Italy and Belgium is motivated by the legal differences that exist in terms of civil rights of homosexual population.

Presently, Belgium represents one of the leading countries in recognizing and protecting civil rights among LGBT people. According to the “Europe Annual Review of the Human Rights Situation of LGBTI People in Europe” (2014) [

24], published by the ILGA (International Lesbian and Gay Association), Belgium is second over 49 European countries taken into consideration by the LGBTI (Lesbians, Gays, Bisexuals, Transsexuals, Intersexuals), whereas Italy ranks 32nd when legislation on civil rights is considered. Since 2003, Belgium has legally recognized civil marriage for same-sex couples, and since 2006, LGBTI persons living in Belgium have had access to legal adoption and medically-assisted procreation procedures. Moreover, strict and rigorous laws regarding hate crime were ratified by the Belgian government, which led to a decrease in aggression and harassment targeting LGBT people. On the contrary, LGBT people in Italy do not enjoy the same legal protections. In fact, no legislation relative to same-sex civil unions exists, and the status of being legally married is not even legally recognized yet. In terms of hate crimes based on sexual orientation and gender identity, the Italian legislature, after a long period of inactivity, recently started to make the first steps forward. In 2013, it was suggested that the “Reale-Mancino” law be extended to include homophobia and transphobia crimes with the aim of sanctioning and condemning actions, behaviors and slogans, inciting violence and discrimination toward minorities.

Furthermore, another purpose of our study is to investigate the perception of social support and the possible connections between internalized homophobia and mental health. It is hypothesized that the two samples will show different levels of internalized homophobia, highlighting the role that the sociocultural environment may have. As Italy a hetero-sexist country in comparison to Belgium, we presume that this sociocultural environment will influence the dimension of internalized homophobia. For this reason we assume that the Italians participants will show higher level of internalized homophobia than Belgian ones [

6].

We also hypothesize: (a) the presence of a significant association between internalized homophobia and psychopathological diseases, such as anxiety and depression, among both samples, in line with previous research data which have underlined a tight link in this sense [

4]; and (b) an inverse relation between presence and level of internalized homophobia with the degree of perceived social support, interpreting the latter as a significant mediation factor in the relation between internalized homophobia and psychological well-being [

21,

25].

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

This study involved two groups of LG people recruited in Italy and Belgium. The number of participants totaled 194 where 86 are Italians and 108 are Belgians (range of age 18–63 years).

The strategy adopted for recruitment could be divided in two steps. Firstly, we presented our research idea to the presidents of all LGBT associations located in the cities of Liege, Belgium, and Padova, Italy. We provided interested associations with our contact information (telephone number and e-mail) and some advertising flyers that described the study. We sent to those who wanted to participate at the study a link by e-mail to complete the questionnaires online or we took an appointment to compile a paper version of the test. The paper version was been completed, only in the presence of the researcher, in an adequate room provided by a LGBT association. Secondly, in an effort to increase the number of study participants, we promoted our research through word of mouth and at the 2013 Gay Pride in Brussels, Belgium where we distributed informational flyers with our contact information. Data was collected over a four-month period (December 2012 to March 2013). Participation in the study was voluntary. Questionnaires in Italian language were provided to Italian participants; in French language to Belgian participants. The questionnaire took approximately 30 min to complete.

Bisexual and under-age participants were excluded from the final sample. Bisexuals were excluded due to a low number of participants.

3.2. Measuring Instrument

A set of self-report instruments were provided to each participant. In addition to obtaining socio-demographic information, the following constructs were measured: anxiety, depression, internalized homophobia, and social support.

Socio-demographic questionnaire. This instrument was created specifically for this research in order to collect socio-demographic information of participants, such as ages, information concerning their coming-out, and relationship status. These factors have been found to be connected with the dimension of the internalized homophobia in literature [

7,

8,

9] and also provide us the information regarding the description of the two samples.

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, y form (STAI-Y) [

26,

27,

28]. The STAI-Y is an instrument used to investigate the Anxiety dimension. The scale is composed of 40 items (20 to investigate state Anxiety, 20 to investigate trait Anxiety), and it is assessed using a 4-point Likert-type scale. For the current study, participants completed only the items concerning the trait Anxiety dimension. Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was α = 0.94 for men and 0.90 for women.

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) [

29,

30,

31]. The BDI-II is a self-report instrument consisting of 21 items evaluated by a 4-point Likert-type scale (item range 0–3, total range 0–63). The scale investigates the intensity of depressive symptoms in adults and adolescents, as well as depression risk in normal population. Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92 for men and 0.89 for women.

Measure of Internalized Sexual Stigma for Lesbians and Gay Men (MISS-LG) [

32]. The MISS-LG is a self-report questionnaire that investigates negative attitudes that gay men, lesbians manifest with respect to both homosexuality and one’s self. This scale is composed of 17 items measured by a 5-point Likert-type scale (scale range 17–85), and it includes three subscales: identity, social disease, and sexuality. The identity subscale denotes an inclination to express a negative self-attitude as gay or lesbian individual, and to consider sexual stigma as a part of identity.

The social disease represents the fear coming from a public identification as homosexual in the social environment and those negative internalized convictions regarding acceptability of homosexuality. The sexuality subscale examines the negative evaluation in terms of quality and duration of intimate same-sex relationships, and the negative view of gay or lesbian sexual behaviors.

Some examples of items related to gay men are: “When I have sex with a man, I feel awkward”; “When I realize that I am demonstrating feminine behaviour, I feel embarrassed”. Some examples of items for lesbians are: “The thought of being lesbian makes me feel depressed”; “Lesbians can only have flings/one- night stands”; “At university (and/or at work), I pretend to be interested in the typical arguments of women”. Cronbach’s alphas for the whole scale were 0.89 for men and 0.87 for women.

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) [

20,

33]. The MSPSS is a 12-item self-report questionnaire which utilizes a 7-point Likert-type scale (scale range 12–84) that assesses one’s personal perception of social support. The scale is subdivided into three subscales (Family, Friends, and Significant Other). Examples items are: “I get the emotional help and support I need from my family”; “My friends really try to help me” Cronbach’s alphas for the total scale were 0.92 for men and 0.85 for women.

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analysis

In the first two tables, we present preliminary analysis of the samples. Firstly, this analysis provides us the information about the demographic variables that are necessary for the discussion of the results. In fact, age, relationship status, and information concerning coming-out could have an impact on the degree of internalized homophobia.

In the women’s groups (

Table 1), the average age of the Italian women is significantly higher from Belgians (

t (85) =4.830,

p < 0.001), while women of the Belgian group disclosed their homosexuality earlier than the Italian group (

t (82) = 3.956,

p < 0.001). Considering that the strategy for the recruitment is the same one for both countries, this difference of age in the two groups could suggest that the way for the Italian lesbian women toward the definition of their own sexual orientation is much longer than Belgian ones. Besides, as reported in

Table 2, the study shows that 77% of the Belgians declared their own sexual orientation to their mother, while among the Italian group, only 51% did (χ

2 [1,

N = 87] = 6.46,

p < 0.05); 71% of the Belgian lesbians also made coming-out with their father, whereas only 44% of Italians did (χ

2 [1,

N = 87] = 6.140,

p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviation of age and age at the time of Coming-Out of each group.

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviation of age and age at the time of Coming-Out of each group.

| Gay men (N = 107) | Lesbians (N = 87) |

|---|

| Italians | Belgians | T test | p value | Italians | Belgians | T test | p value |

|---|

| | M | SD | M | SD | t value | p | M | SD | M | SD | t value | p |

| Age | 29.6 | 8.64 | 27.3 | 9.30 | 1.325 | 0.188 | 35.5 | 8.77 | 26.2 | 7.21 | 4.83 | 0.000 |

| C.O | 20.2 | 5.10 | 20.1 | 4.52 | 0.098 | 0.922 | 24.5 | 7.26 | 19.1 | 5.13 | 3.95 | 0.000 |

Table 2.

Percent frequencies and significances regarding demographic variables.

Table 2.

Percent frequencies and significances regarding demographic variables.

| | Gay men | Lesbians |

|---|

| Demographical variables | Italians | Belgians | p value | Italians | Belgians | p value |

| % | % | p | % | % | p |

| Coming-out to mother | 62.8 | 78.1 | 0.08 | 51.2 | 77.3 | 0.01 * |

| Coming-out to father | 60.5 | 68.8 | 0.38 | 44.2 | 70.5 | 0.01 * |

| Coming out other family member | 51.28 | 71.9 | 0.03 * | 48.8 | 63.6 | 0.16 |

| Relationship status | | | 0.20 | | | 0.00 ** |

| Single | 34.9 | 50 | | 11.6 | 47.7 | |

| Couple | 34.9 | 34.4 | | 20.9 | 36.4 | |

| Cohabitation | 18.6 | 7.8 | | 62.8 | 9.1 | |

| Married | 4.7 | 6.3 | | 0 | 4.5 | |

| Other | 7 | 1.6 | | 2.3 | 0 | |

| Divorced | 0 | 0 | | 2.3 | 2.3 | |

Finally, considering the relationship status, 48% of the Belgian women were single, while 63% of the Italian lived together with their partner (χ

2 [5,

N = 86] = 31.86,

p < 0.001), Chi-square analysis have shown that, for what concerns gay men (

Table 2): disclosure of sexual orientation to other family members (χ

2 [1,

N = 107] = 4.76,

p < 0.05), 72% of Belgians disclosed their homosexuality to some relatives, whereas 51% of Italians did so.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Differences between Italian and Belgian

For what concerns the first goal of this study, due to socio-political differences between the countries, we have hypothesized to observe higher levels of internalized homophobia, anxiety and depression in Italians participants.

In t test analysis (

Table 3), some significant results have emerged by comparing the two groups of Italians and Belgians gay men, regarding the degree of internalized homophobia: significant results were obtained in the total internalized homophobia variable,

t (105) = −2.63,

p < 0.05, in the social disease,

t (105) = −2.87,

p < 0.01, and sexuality,

t (105) = −2.07,

p < 0.05, dimensions of the questionnaire.

Table 3.

Mean, standard deviation, t value and p value comparing Italian and Belgian gay men’s samples.

Table 3.

Mean, standard deviation, t value and p value comparing Italian and Belgian gay men’s samples.

| Measuring Instrument | Italians (N = 43) | Belgians (N = 64) | | |

|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t value | p |

|---|

| STAI-Y | 42.35 | 12.89 | 43.52 | 10.80 | −0.51 | 0.614 |

| BDI | 10.95 | 11.37 | 9.40 | 7.68 | 0.85 | 0.400 |

| HIT | 1.59 | 0.57 | 1.92 | 0.69 | −2.63 | 0.010 * |

| HIS | 1.71 | 0.69 | 2.19 | 0.91 | 2.87 | 0.005 ** |

| HISE | 1.46 | 0.44 | 1.67 | 0.54 | −2.07 | 0.41 * |

| HII | 1.53 | 0.80 | 1.81 | 0.96 | −1.54 | 0.126 |

| MSPSS | 64.98 | 13.89 | 65.36 | 13.17 | 0.87 | 0.886 |

We hypothesized an effect of the participant’s age on the dimensions of internalized homophobia, for these reasons, we have checked the effects on the “Age” and “Country” variables by the ANCOVA statistical analysis. The significant result, regarding sexuality dimension, was falsified, F (1,104) = 3.467, 0.05. Contrary results haven’t shown significant differences regarding anxiety, depression and perceived social support.

For Lesbian groups, as it can be seen in

Table 4, the analysis shows no significant differences among the two groups in all studied dimensions, contrary to the subscale regarding “Sexuality” in the MISS-L questionnaire. This significant difference has been falsified by the ANCOVA analysis that demonstrated the effect of the variable “Age” on the “Nationality” cancelled the significance bond to the scores (F (1,84) = 0.978,

p = 0.326).

Table 4.

Mean, standard deviation, t value and p value comparing Italian and Belgian lesbian’s groups.

Table 4.

Mean, standard deviation, t value and p value comparing Italian and Belgian lesbian’s groups.

| Measuring Instruments | Italians (N = 43) | Belgians (N = 44) | | |

|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t value | p |

|---|

| STAI-Y | 39.79 | 8.69 | 43.23 | 9.20 | −1.79 | 0.077 |

| BDI | 8.35 | 7.81 | 10.98 | 8.40 | −1.51 | 0.134 |

| HIT | 1.41 | 0.42 | 1.51 | 0.57 | −0.99 | 0.327 |

| HIS | 1.57 | 0.64 | 1.56 | 0.70 | 0.09 | 0.928 |

| HISE | 1.15 | 0.25 | 1.29 | 0.36 | −2.12 | 0.037 * |

| HII | 1.44 | 0.58 | 1.68 | 1.01 | −1.33 | 0.187 |

| MSPSS | 68.74 | 9.26 | 67.77 | 11.87 | 0.43 | 0.672 |

4.3. Correlations and Path Analysis

As regards the second goal, we hypothesized significant correlation between internalized homophobia and psychological diseases (anxiety and depression).

Table 5 and

Table 6 show the results of the correlation analysis. We use these analyses in order to study the relationship between the variables. In both samples, the anxiety and the depression are significantly correlated with internalized homophobia, whereas in the gay men the social support has a negative correlation with Internalized Homophobia. In lesbians, the internalized homophobia is not significantly correlated with social support. The anxiety shows also a positive correlation with depression, furthermore, both anxiety and depression, are significantly negatively correlated with social support.

Table 5.

Bivariate Pearson correlations among the instruments, in the two lesbian populations: the superior triangle refers to the Italian participants (N = 43), the inferior triangle to the Belgian participants (N = 44).

Table 5.

Bivariate Pearson correlations among the instruments, in the two lesbian populations: the superior triangle refers to the Italian participants (N = 43), the inferior triangle to the Belgian participants (N = 44).

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|

| Instruments | | | | |

| 1 STAI-Y | - | 0.726 ** | −0.646 ** | 0.332 * |

| 2 BDI | 0.720 ** | - | −0.332 * | 0.346 * |

| 3 MSPSS | −0.552 ** | –0.371 * | - | −0.292 |

| 4 MISS-L | 0.286 | 0.166 | −0.050 | - |

Table 6.

Bivariate Pearson correlations among the instruments, in the two masculine populations: the superior triangle refers to the Italian participants (N = 43), the inferior triangle to the Belgian participants (N = 64).

Table 6.

Bivariate Pearson correlations among the instruments, in the two masculine populations: the superior triangle refers to the Italian participants (N = 43), the inferior triangle to the Belgian participants (N = 64).

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|

| Instruments | | | | |

| STAI-Y | - | 0.784 ** | −0.642 ** | 0.765 ** |

| BDI | 0.704 ** | - | −0.332 * | 0.709 ** |

| MSPSS | −0.497 ** | −0.502 ** | - | −0.577 ** |

| MISS-L | 0.547 ** | 0.558 ** | −0.050 ** | - |

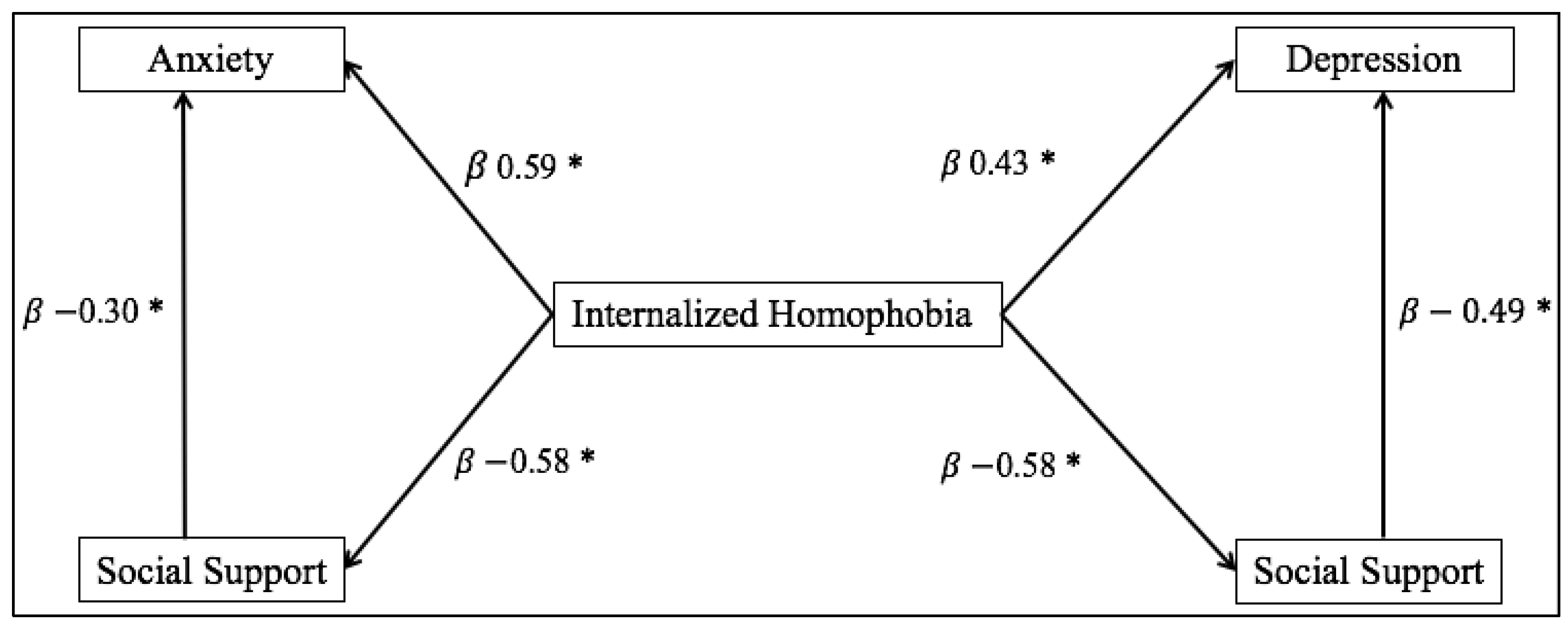

The third goal was to verify the role of social support in influencing the development of internalized homophobia, anxiety and depression disorders. The correlation analysis shows that the perceived social support can diminish the symptomatology of anxiety and depression. For that reason, we have hypothesized that the social support is a significant mediator between internalized homophobia and Mental Health. To this purpose we performed Path Analysis using LISREL 8.70 with the ML estimation method, where internalized homophobia is the independent variable, social support the mediator, anxiety and depression the dependents variables. We have performed Path Analysis only for the Gay men group as we did not find statistical differences between the two lesbian group regarding the observed dimensions. The direct effects are shown in the following figures. As regard the indirect effects, the two models show that the social support is a significant mediator between internalized homophobia and psychological heath (depression and anxiety) for both samples: Italian and Belgian. Nevertheless, the indirect effect is higher in the Italian group than in the Belgian one.

Figure 1 reports standardized path coefficients for the Italian group; two significant direct effects emerged: the first one regards the degree of internalized homophobia, which had an effect on the levels of anxiety, depression and social support; the second one regards the degree of perceived social support, which influenced the levels of anxiety reported and symptoms of depression. Furthermore, the indirect effect of internalized homophobia on anxiety, mediated by social support, is significant β = 0.17,

p < 0.05; the indirect effect of internalized homophobia on depression is also significant β = 0.28,

p < 0.05.

Figure 1.

Path Analysis Model of relation between Internalized Homophobia variables, Anxiety, Depression, and Social Support among the male Italian sample, * p < 0.05.

Figure 1.

Path Analysis Model of relation between Internalized Homophobia variables, Anxiety, Depression, and Social Support among the male Italian sample, * p < 0.05.

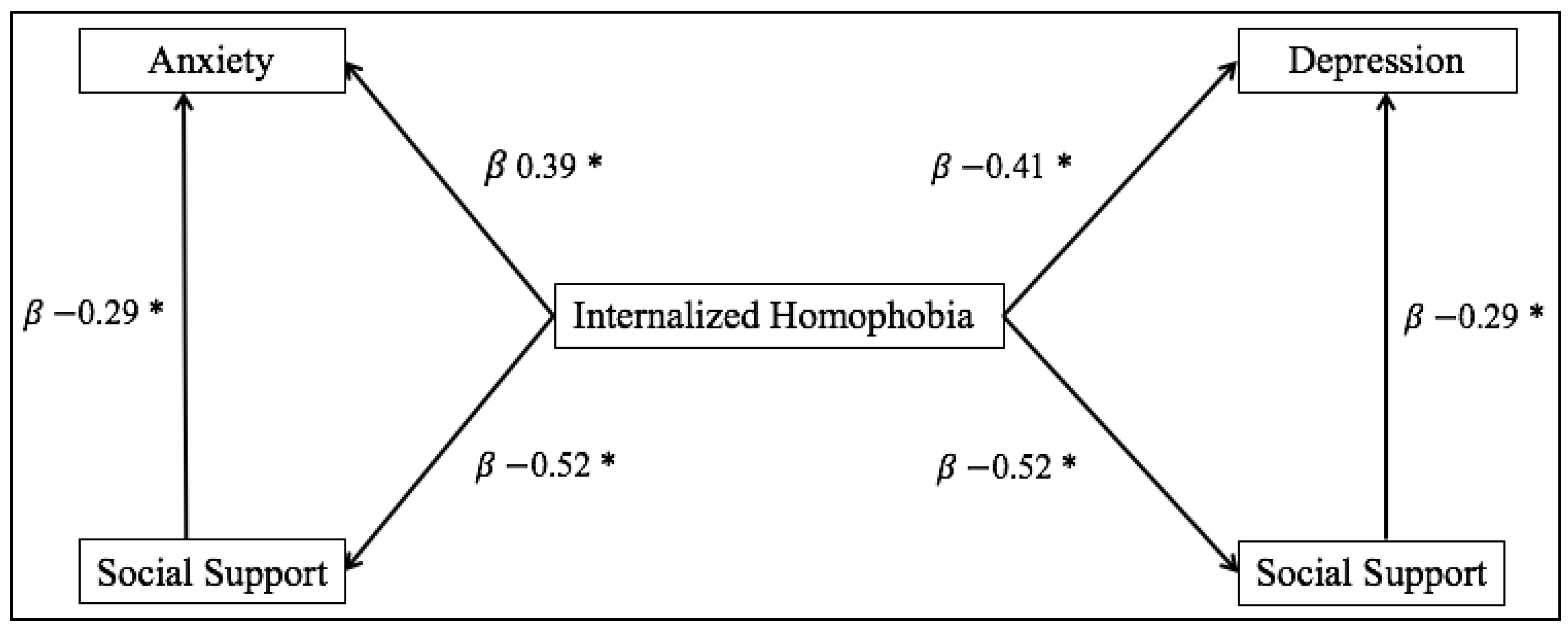

Figure 2 reports standardized path coefficients for the Belgian group; two significant direct effects need to be underlined in this sample, as well as in the Italian group: the first one concerns the degree of internalized homophobia which had a role in influencing the levels of anxiety, depression and social support; the second one regards the degree of perceived social support which is related to the levels of anxiety and symptoms of depression. Considering this sample, the indirect effect of internalized homophobia on anxiety is significant β = 0.15,

p < 0.05; as well as the indirect effect of internalized homophobia on depression β = 0.15,

p < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Path Analysis Model of relation between interiorized homophobia variables, anxiety, depression and Social Support among the male Belgian sample, * p < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Path Analysis Model of relation between interiorized homophobia variables, anxiety, depression and Social Support among the male Belgian sample, * p < 0.05.

5. Discussion

In light of the analyses conducted in this study, our first hypothesis has not been confirmed. Belgian gay men have obtained mean scores of internalized homophobia significantly higher than the Italian gay men sample. This contradiction in the results could suggest that the internalized homophobia could be associated to intrapersonal and interpersonal dimensions such as significant relationships that should be investigated in future studies. In support of this hypothesis, the Belgian group is composed of 50% singles while the Italian group is composed of 58% individuals who are in couples or live together. Moreover, we hypothesized that responses from the Italian gay men in relation to the internalized homophobia dimension might have been influenced, consciously or not, by their strong desire to offer a healthy complete and positive own “homosexual” group image.

In the last few years, the debate about LGBT civil rights in Italy has increased considerably. In this context LGBT associations promote a culture of respect for differences in order to improve the quality of life of LGBT people and to obtain civil rights protections. However, it is necessary to affirm that results cannot be generalized due to our convenient samples.

The second hypothesis, regarding possible correlations between internalized homophobia and mental health disorders, such as anxiety and depression, was supported. The correlation confirmed previous works presented in literature, in both lesbian and gay men groups [

4,

21]. A strict relation between internalized homophobia, mental health problems and social support has been observed in both the lesbian’s and gay men’s groups. Results that emerged from the current study, in fact, emphasize how high levels of internalized homophobia are associated to high levels of psychological diseases [

4,

21].

Concerning the third hypothesis, differences between levels of perceived social support of the two groups were observed. According to our expectations, social support resulted in being negatively correlated to internalized homophobia; at the same time, high levels of social support are correlated to low levels of psychopathological diseases (anxiety and depression ) [

5,

21,

25]. Path analyses allowed to observe the effective role of mediation of the perceived social support variable in relation to the levels of internalized homophobia and mental health (considering anxiety and depression) among both groups. The relevant direct effect of homophobia influencing mental health was also underlined: this kind of influence seems stronger than an indirect influence.

Generally the results have emphasized that, in both groups, the perceived social support indirectly influence the mental health of the LG people, increasing the sense of psychological well-being. These aspects are in line with current literature; in fact, the social support represents an important factor of protection for the psychological health of the gay people. This is happening regardless of the country in which they live, and recognition of the civil rights for the people LG.

The manifestations of homophobia, especially in the most advanced countries with regard to social rights, have the tendency to be revealed in a subtle and veiled way. These results offer some valuable indications to the experts who operate in this field, regarding the implications of internalized homophobia in the process of construction one’s identity; for this reason early interventions, for example in the school environment, could be increased.