EU Development Aid towards Sub-Saharan Africa: Exploring the Normative Principle

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theories of Aid

Flows of official financing administered with the promotion of the economic development and welfare of developing countries as the main objective, and which are concessional in character with a grant element of at least 25 percent (using a fixed 10 percent rate of discount). By convention, ODA flows comprise contributions of donor government agencies, at all levels, to developing countries (“bilateral ODA”) and to multilateral institutions. ODA receipts comprise disbursements by bilateral donors and multilateral institutions. Lending by export credit agencies—with the pure purpose of export promotion—is excluded.[14]

2.2. EU Normative Power

In its relations with the wider world, the Union shall uphold and promote its values and interests and contribute to the protection of its citizens. It shall contribute to peace, security, the sustainable development of the Earth, solidarity and mutual respect among peoples, free and fair trade, eradication of poverty and the protection of human rights, in particular the rights of the child, as well as to the strict observance and the development of international law, including respect for the principles of the United Nations Charter.[29]

The Union’s action on the international scene shall be guided by the principles which have inspired its own creation, development and enlargement, and which it seeks to advance in the wider world: democracy, the rule of law, the universality and indivisibility of human rights and fundamental freedoms, respect for human dignity, the principles of equality and solidarity, and respect for the principles of the United Nations Charter and international law.[29]

Combating global poverty is a moral obligation. In such a world, we would not allow 1200 children to die of poverty every hour. Development policy is at the heart of the EU’s relations with all developing countries. The Member States and the Community are equally committed to basic principles, fundamental values and the development objectives agreed at the multilateral level.[31]

The Union shall define and pursue common policies and actions, and shall work for a high degree of cooperation in all fields of international relations, in order to foster the sustainable economic, social and environmental development of developing countries.[29]

The Union shall define and pursue common policies and actions, and shall work for a high degree of cooperation in all fields of international relations, in order to promote an international system based on stronger multilateral cooperation and good global governance.[29]

A collective responsibility to uphold the principles of human dignity, equality and equity at the global level. As leaders we have a duty therefore to all the world’s people, especially the most vulnerable and, in particular, the children of the world, to whom the future belongs.[32]

2.3. Motivations for EU’s Development Aid toward African, Caribbean and Pacific States

2.4. Domestic Factors and EU Aid Policy

3. Methods

3.1. Research Question and Hypotheses

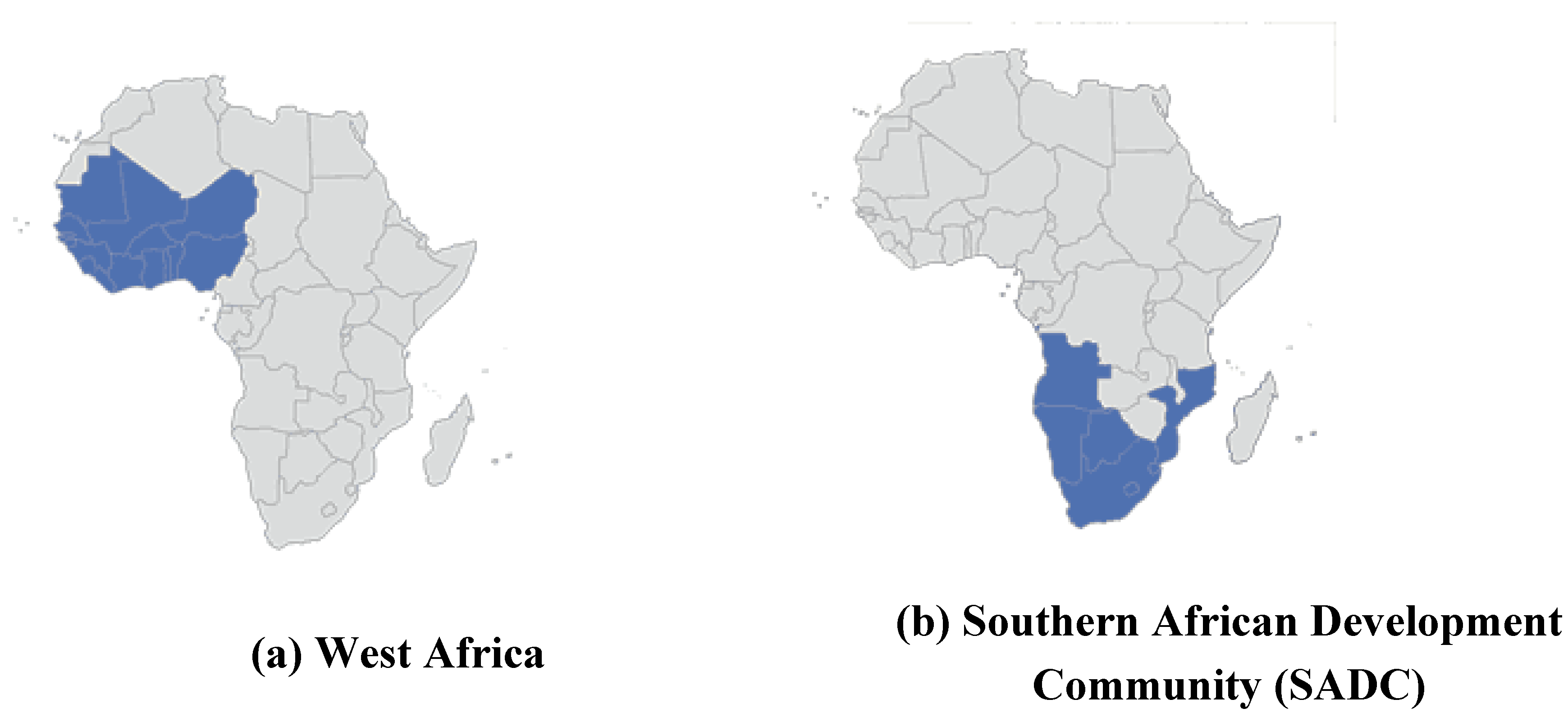

3.2. Population

3.3. Study Design and Analysis

- Political stability (PolStab): This variable is the “Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism” index [88]. It captures perceptions of the likelihood that the government will be destabilized or overthrown by unconstitutional or violent means, including politically-motivated violence and terrorism. The estimate gives the country’s score on the aggregate indicator, in units of a standard normal distribution, i.e., ranging from −2.5 (weak) to 2.5 (strong governance performance).

- Carbon dioxide emissions (CO2em): We use the weighted average of the CO2 emissions (kg per 2000 US$ of GDP) index, which represents the carbon dioxide emissions stemming from the burning of fossil fuels and the manufacturing of cement. They include carbon dioxide produced during consumption of solid, liquid and gas fuels and gas flaring.

- Mortality rate of children under five years old (Mortality): Child mortality is claimed to be one of the most crucial of the EU and UN priorities within the framework of the Millennium Development Goals for improving health and welfare worldwide [78]. We use the weighted average of the mortality rate, under-5 (per 1000) index, which shows the probability per 1000 that a new-born baby will die before reaching age five, if subject to current age-specific mortality rates.

- Foreign direct investment (FDI): FDI entails entrepreneurial issues of ownership and control over enterprises within foreign business environments. The OECD defines FDI as a private investment made for the purposes of acquiring a “lasting interest in an enterprise”. This implies “a long term relationship where the direct investor has a significant influence on the management of the enterprise reflected by ownership of at least 10% of the shares, or equivalent voting power or other means of control”. We selected the net outflows of FDI as a percentage of GDP. FDI is the net inflows of investment to acquire a lasting management interest in an enterprise operating in an economy other than that of the investor. It is the sum of equity capital, reinvestment of earnings, other long-term capital and short-term capital, as shown in the balance of payments.

- Trade export volume (TrExpVol): The trade export volume index shows the volume of total products exported from Sub-Saharan-African states.

- Military expenditure (MilExp): Realists consider military force the most important power capability. Military expenditures as a percentage of GDP include all current and capital expenditures on the armed forces, including peacekeeping forces, defence ministries and other government agencies engaged in defence projects, paramilitary forces, if these are judged to be trained and equipped for military operations, and military space activities. Such expenditures include military and civil personnel, including retirement pensions of military personnel and social services for personnel, operation and maintenance, procurement and military research and development.

- Natural resource rents (NatResRent): The total natural resource rents as a percentage of GDP is the weighted average of the sum of oil rents, natural gas rents, coal rents (hard and soft), mineral rents and forest rents.

4. Results

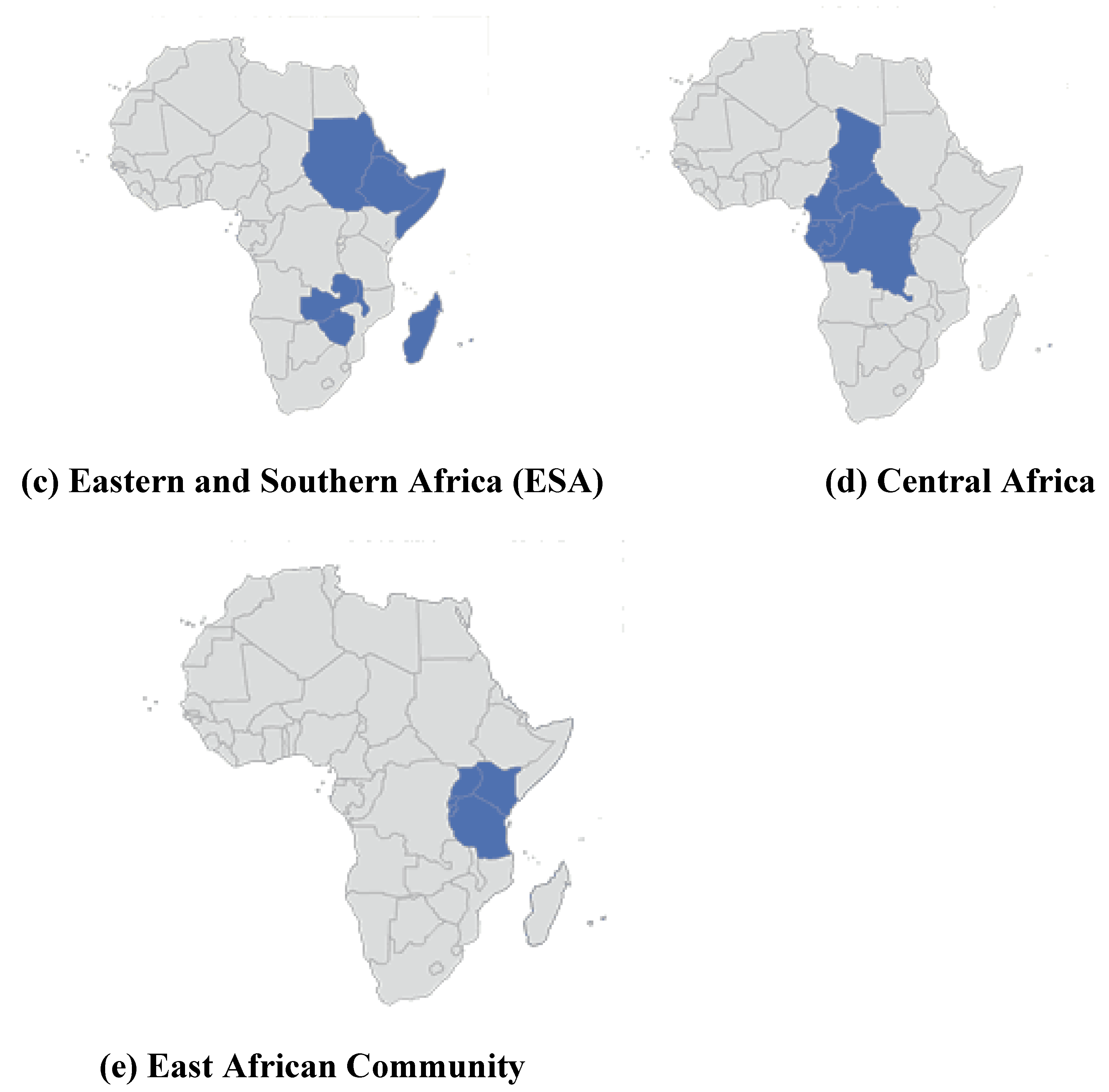

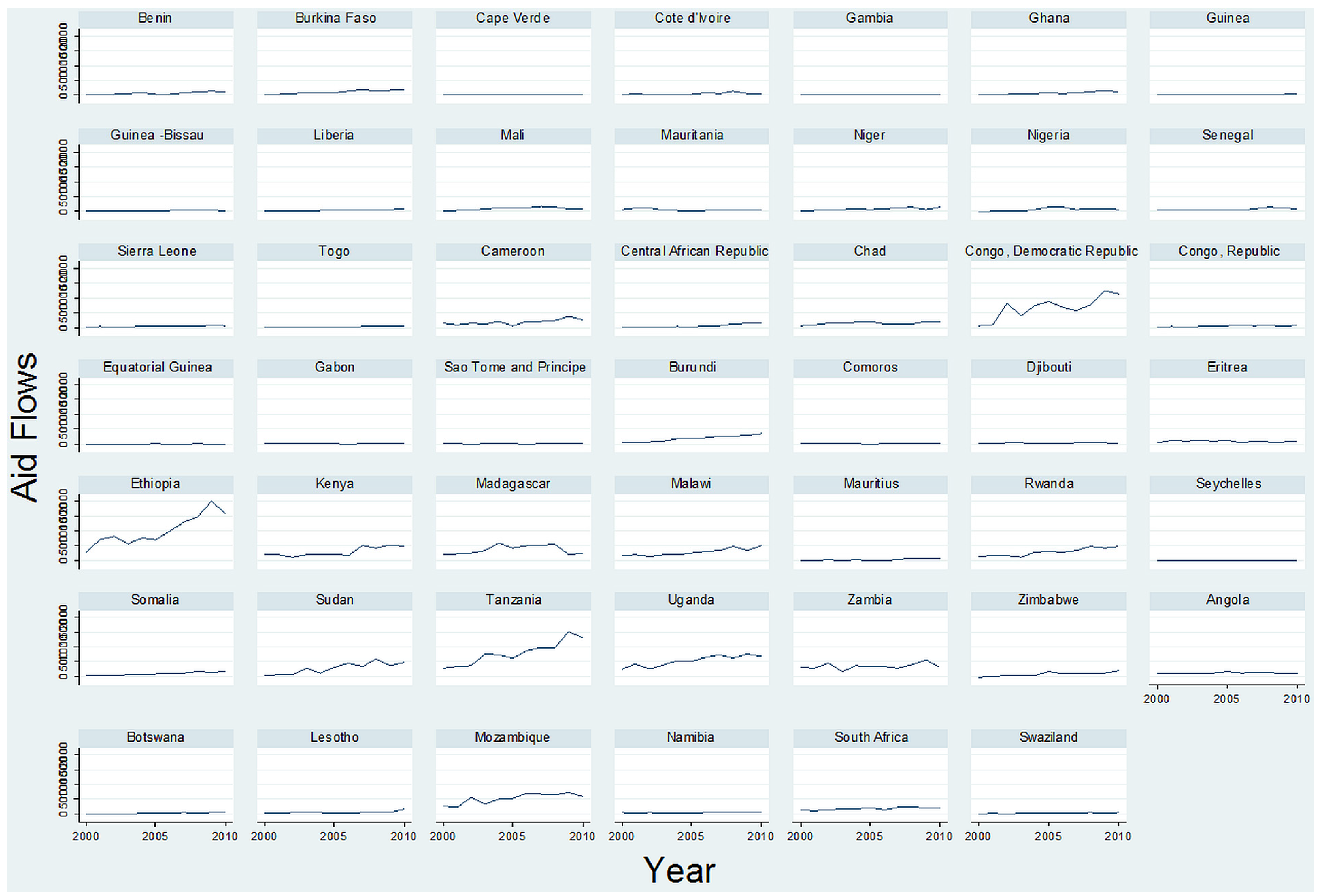

4.1. Descriptive Results

4.2. Correlations

| Correlations | Aid flows | Rule of law | Political stability | Corruption | Participation and human rights | Sustainable economic opportunity | CO2 emissions | Mortality rate | % Primary education completion | FDI | Procedures to start a business | Trade export volume | Military expenditure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rule of law | −0.043 | ||||||||||||

| Political stability | −0.222 ** | 0.803 ** | |||||||||||

| Corruption | −0.093 * | 0.891 ** | 0.693 ** | ||||||||||

| Participation and human rights | −0.021 | 0.830 ** | 0.690 ** | 0.746 ** | |||||||||

| Sustainable economic opportunity | −0.021 | 0.943 ** | 0.795 ** | 0.862 ** | 0.902 ** | ||||||||

| CO2 emissions | −0.036 | 0.016 | 0.025 | 0.097 | −0.016 | 0.074 | |||||||

| Mortality rate | 0.062 | −0.633 ** | −0.510 ** | −0.644 ** | −0.461 ** | −0.674 ** | −0.304 ** | ||||||

| % Primary education completion | −0.121 * | 0.647 ** | 0.531 ** | 0.584 ** | 0.578 ** | 0.718 ** | 0.325 ** | −0.772 ** | |||||

| FDI | 0.098 * | −0.022 | −0.146 ** | −0.021 | −0.004 | 0.022 | 0.257 ** | −0.023 | 0.161 ** | ||||

| Procedures to start a business | −0.007 | −0.305 ** | −0.149 * | −0.330 ** | −0.333 ** | −0.303 ** | −0.025 | 0.156 ** | −0.189 ** | −0.109 | |||

| Trade export volume | 0.076 | −0.088 | −0.015 | −0.114 * | −0.009 | −0.094 * | −0.070 | 0.293 ** | −0.264 ** | −0.043 | 0.167 ** | ||

| Military expenditure | −0.067 | −0.132 * | −0.164 ** | −0.007 | −0.293 ** | −0.229 ** | 0.196 ** | 0.035 | −0.238 ** | −0.086 | 0.234 ** | 0.036 | |

| Total natural resources rents | −0.050 | −0.419 ** | −0.248 ** | −0.484 ** | −0.450 ** | −0.442 ** | 0.092 | 0.233 ** | −0.186 ** | 0.208 ** | 0.237 ** | 0.118 ** | 0.029 |

4.2.1. Correlations with Aid Flows

4.2.2. Other Correlations

4.3. OLS Regression Models

4.3.1. Overall Model

| Variable | Coefficient | 95% CI a | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 544.678 | 378.486–710.870 | <0.0001 | |

| PolStab | −22.872 | −64.050–180.306 | 0.275 | |

| CO2em | 58.274 | −86.773–2030.321 | 0.429 | |

| Mortality | −5.068 | −6.326–(−30.810) | <0.0001 | |

| FDI | 0.000 | 0.000–0.000 | 0.135 | |

| TrExpVol | 0.184 | 0.063–0.305 | 0.003 | |

| MilExp | −9.781 | −20.017–0.456 | 0.061 | |

| NatResRent | −0.852 | −3.227–10.523 | 0.480 | |

| Country | ||||

| Benin | 157.533 | 40.990–2740.075 | 0.008 | |

| Burkina Faso | 472.408 | 311.373–6330.444 | <0.0001 | |

| Cape Verde | −329.923 | −458.229–(−2010.616) | <0.0001 | |

| Cote D’Ivoire | 130.033 | −4.928–2640.994 | 0.059 | |

| Gambia | 19.434 | −105.880–1440.748 | 0.760 | |

| Ghana | −67.213 | −168.658–340.231 | 0.193 | |

| Guinea | 288.772 | 146.129–4310.416 | <0.0001 | |

| Guinea-Bissau | 321.530 | 173.031–4700.029 | <0.0001 | |

| Liberia | 92.939 | −25.156–2110.034 | 0.122 | |

| Mali | 563.242 | 384.324–7420.161 | <0.0001 | |

| Mauritania | 83.635 | −32.236–1990.506 | 0.156 | |

| Niger | 461.499 | 298.004–6240.995 | <0.0001 | |

| Nigeria | 284.198 | 111.721–4560.675 | 0.001 | |

| Senegal | −17.844 | −118.793–830.106 | 0.728 | |

| Sierra Leone | 326.864 | 139.027–5140.701 | 0.001 | |

| Togo | −8.977 | −126.281–1080.327 | 0.880 | |

| Cameroon | 322.132 | 209.996–4340.268 | <0.0001 | |

| Central African Republic | 299.262 | 156.538–4410.987 | <0.0001 | |

| Chad | 442.398 | 272.222–6120.574 | <0.0001 | |

| Democratic Republic of Congo | 787.600 | 630.072–9450.127 | <0.0001 | |

| Republic of Congo | 10.270 | −180.455–2000.995 | 0.916 | |

| Gabon | −79.822 | −234.502–740.857 | 0.310 | |

| Burundi | 384.085 | 246.944–5210.226 | 0.000 | |

| Djibouti | −26.868 | −127.992–740.257 | 0.601 | |

| Eritrea | 147.317 | −144.670–4390.304 | 0.321 | |

| Ethiopia | 815.083 | 709.867–9200.299 | 0.000 | |

| Kenya | 112.051 | 8.549–2150.552 | 0.034 | |

| Madagascar | 242.132 | 146.738–3370.526 | 0.000 | |

| Malawi | 330.789 | 233.348–4280.230 | 0.000 | |

| Mauritius | −485.934 | −626.523–(−3450.345) | 0.000 | |

| Rwanda | 353.653 | 241.378–4650.928) | 0.000 | |

| Seychelles | −523.433 | −687.157–(−3590.708) | 0.000 | |

| Sudan | 149.698 | 21.253–2780.142 | 0.023 | |

| Variable | Coefficient | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Tanzania | 619.622 | 517.498–7210.746 | 0.000 | |

| Uganda | 515.714 | 400.230–6310.198 | 0.000 | |

| Zambia | 453.032 | 333.753–5720.310 | 0.000 | |

| Zimbabwe | −82.626 | −336.710–1710.457 | 0.522 | |

| Angola | 482.932 | 285.706–6800.157 | 0.000 | |

| Botswana | −165.111 | −269.147–(−610.076) | 0.002 | |

| Mozambique | 737.129 | 606.944–8670.313 | 0.000 | |

| Namibia | −192.517 | −301.588–(−830.447) | 0.001 | |

| South Africa | −158.311 | −464.871–1480.248 | 0.310 | |

| Swaziland | 0 b |

4.3.2. OLS Regression by Regions

| Variable | Coefficients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| West Africa | Central Africa | Eastern and Southern Africa | East African Community | Southern Africa | |

| Intercept | 282.482 * | −264.299 | 833.528 * | 423.522 | −157.351 |

| PolStab | 15.7452 | 94.104 | −187.926 * | −102.201 | −14.829 |

| CO2em | 84.1072 | 444.728 | −43.594 | 596.147 * | 38.069 |

| Mortality | −2.8562 * | 1.672 | −7.827 * | −4.825 * | 0.217 |

| FDI | 7.300 × 10−9 | 3.706 × 10−8 | 1.23 × 10−7 * | 1.03 × 10−7 | 1.259 × 10−8 * |

| TrExpVol | 0.081 * | 0.283 | 0.198 | 1.942* | 0.963 * |

| MilExp | 9.2261 | 35.645 | −13.480 * | −104.309 | −7.499 |

| NatResRent | 1.162 | −2.199 | −12.150 | 41.807 * | 3.177 |

| Country | |||||

| Benin | 94.098 * | ||||

| Burkina Faso | 313.285 * | ||||

| Cape Verde | −199.685 * | ||||

| Cote D’Ivoire | 135.865 * | ||||

| Gambia | 15.678 | ||||

| Ghana | −14.598 | ||||

| Guinea | 180.583 | ||||

| Guinea-Bissau | 168.076 | ||||

| Liberia | 73.559 | ||||

| Mali | 340.781 | ||||

| Mauritania | −1.685 | ||||

| Niger | 301.544 | ||||

| Nigeria | 168.366 | ||||

| Senegal | 10.920 | ||||

| Sierra Leone | 211.227 | ||||

| Togo | 0 | ||||

| Cameroon | 18.410 | ||||

| Central African Republic | 0.093 | ||||

| Chad | 17.894 | ||||

| Democratic Republic of Congo | 416.803 | ||||

| Republic of Congo | 135.513 | ||||

| Gabon | 0 | ||||

| Djibouti | −20.937 | ||||

| Eritrea | 186.773 | ||||

| Ethiopia | 758.528 * | ||||

| Madagascar | 259.085 | ||||

| Malawi | 11.744 * | ||||

| Mauritius | −534.668 * | ||||

| Seychelles | −529.142 * | ||||

| Sudan | −87.802 | ||||

| Zambia | 760.631 * | ||||

| Zimbabwe | 0 | ||||

| Burundi | −172.066 | ||||

| Kenya | −448.298 * | ||||

| Rwanda | 55.904 | ||||

| Tanzania | 108.876 | ||||

| Uganda | 0 | ||||

| Angola | −112.580 | ||||

| Botswana | 39.817 | ||||

| Mozambique | 315.081 * | ||||

| Namibia | 76.918 | ||||

| South Africa | 78.592 | ||||

| Swaziland | 0 | ||||

| R-square | 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.95 |

| F | 9.813 | 6.793 | 29.4 | 19.5 | 48.4 |

| p | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Abbreviations

| ACP | African, Caribbean and Pacific; |

| CPA | Cotonou Partnership Agreement; |

| EAC | East African Community; |

| ESA | Eastern and Southern Africa; |

| EU | European Union; |

| FDI | foreign direct investment; |

| GDP | gross domestic product; |

| GNI | gross national income; |

| IMF | International Monetary Fund; |

| MDG | Millennium Development Goal; |

| NGO | non-governmental organization; |

| ODA | official development assistance; |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; |

| QWIDS | Query Wizard for International Development Statistics; |

| SADC | Southern Africa Development Community; |

| SD | standard deviation; |

| UK | United Kingdom; |

| UN | United Nations; |

| U.S. | United States of America; |

| WTO | World Trade Organization. |

Appendix A: Panel Data Analysis

| Variable | Coefficients | Difference | S.E. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fixed | random | |||

| PolStab | −20.609 | −50.146 | 29.537 | 24.184 |

| CO2em | 173.01 | −18.68 | 191.70 | 142.25 |

| fdi | −3.91 × 10−9 | 2.69 × 10−9 | −6.61 × 10−9 | 2.82 × 10−9 |

| TrExpVol | 0.201 | 0.158 | 0.042 | 0.049 |

| MilExp | −22.538 | −23.458 | 0.920 | 7.328 |

| NatResRent | −0.185 | −0.208 | 0.023 | 2.272 |

| Mortality | −6.288 | −0.901 | −5.387 | 1.825 |

| ProcBus | −7.709 | −10.664 | 2.954 | 3.338 |

| b = consistent under H0 and Ha; obtained from Stata command xtreg | ||||

| B = inconsistent under Ha, efficient under H0; obtained from xtreg | ||||

Appendix B

| Variable | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Aid Flows | 163.06 | 248.81 |

| Rule of Law | −0.7361 | 0.6656 |

| Political Stability | −0.5475 | 0.9605 |

| Corruption | −0.6180 | 0.5937 |

| Participation and Human Rights | 47.2345 | 17.1839 |

| Sustainable Economic Opportunity (Overall) | 48.3059 | 14.3669 |

| CO2 Emissions (kg per 2000 US$ of GDP) | 0.5123 | 0.4878 |

| Mortality Rate | 120.4596 | 45.7662 |

| Percentage of Primary Education Completion | 59.7830 | 22.7393 |

| FDI | 4.2539 | 1.09146 |

| No. of Procedures Required to Start a Business | 10.05 | 3.335 |

| Trade Export Volume | 165.7956 | 171.0897 |

| Military Expenditure (% of GDP) | 2.2406 | 2.8261 |

| Total Natural Resource Rents (% of GDP) | 12.0264 | 17.7715 |

| Country | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Benin | 52.987 | 41.925 |

| Burkina Faso | 108.381 | 50.782 |

| Cape Verde | 16.937 | 8.998 |

| Cote d’Ivoire | 56.966 | 51.825 |

| Gambia | 3.958 | 3.082 |

| Ghana | 67.076 | 30.024 |

| Guinea | 35.330 | 13.618 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 18.920 | 2.676 |

| Liberia | 38.426 | 13.913 |

| Mali | 108.902 | 54.077 |

| Mauritania | 51.557 | 32.265 |

| Niger | 71.580 | 48.194 |

| Nigeria | 69.477 | 58.281 |

| Senegal | 58.585 | 39.897 |

| Sierra Leone | 48.563 | 25.916 |

| Togo | 14.250 | 16.586 |

| Cameroon | 170.520 | 51.216 |

| Central African Republic | 36.234 | 19.190 |

| Chad | 151.665 | 45.926 |

| Congo, Democratic Republic | 499.988 | 272.774 |

| Congo, Republic | 59.781 | 28.088 |

| Gabon | 19.412 | 11.666 |

| Burundi | 156.082 | 77.983 |

| Djibouti | 29.621 | 8.608 |

| Eritrea | 94.050 | 38.179 |

| Ethiopia | 771.460 | 312.285 |

| Kenya | 226.902 | 125.859 |

| Madagascar | 395.292 | 148.394 |

| Malawi | 229.925 | 70.881 |

| Mauritius | 14.425 | 8.5865 |

| Rwanda | 232.497 | 87.137 |

| Seychelles | 5.857 | 2.1207 |

| Sudan | 207.773 | 162.73 |

| Tanzania | 663.528 | 257.43 |

| Uganda | 477.457 | 178.84 |

| Zambia | 343.590 | 36.307 |

| Zimbabwe | 60.138 | 68.784 |

| Angola | 131.074 | 19.736 |

| Botswana | 18.848 | 16.410 |

| Mozambique | 515.667 | 155.635 |

| Namibia | 45.268 | 15.927 |

| South Africa | 171.745 | 35.888 |

| Swaziland | 21.978 | 9.872 |

| Total | 154.704 | 206.690 |

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Harry S. Truman. “Inaugural Address of the President.” Department of State Bulletin 20 (1949): 123–26. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph Wright, and Matthew Winters. “The Politics of Effective Foreign Aid.” Annual Review of Political Science 13 (2010): 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter Blunt, and Henrik Lindroth. “Development’s Denial of Social Justice.” International Journal of Public Administration 35 (2012): 471–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter Blunt, Mark Turner, and Jana Hertz. “The meaning of development assistance.” Public Administration and Development 31 (2011): 172–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambisa Moyo. Dead Aid: Why Aid is not Working and How There is a Better Way for Africa. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Adrian Hyde-Price. “‘Normative’ power Europe: A realist critique.” Journal of European Public Policy 13 (2006): 217–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberto Alesina, and David Dollar. “Who Gives Foreign Aid to Whom and Why? ” Journal of Economic Growth 5 (2000): 33–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristos Doucouliagos, and Martin Paldam. “The ineffectiveness of development aid on growth: An update.” European Journal of Political Economy 27 (2011): 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viktor Brech, and Niklas Potrafke. “Donor ideology and types of foreign aid.” Journal of Comparative Economics 42 (2014): 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David Halloran Lumsdaine. Moral Vision in International Politics: The Foreign Aid Regime, 1949–1989. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Alfred Maizels, and Machiko K. Nissanke. “Motivations for Aid to Developing-Countries.” World Development 12 (1984): 879–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David H. Bearce, and Daniel C. Tirone. “Foreign Aid Effectiveness and the Strategic Goals of Donor Governments.” Journal of Politics 72 (2010): 837–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert Cassen, and Associates. Does Aid Work? Report to an Intergovernmental Task Force. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). External Debt Statistics: Guide for Compilers and Users. Washington, DC: IMF, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Maurizio Carbone. The European Union and International Development: The Politics of Foreign Aid. New York: Routledge, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon Cumming. Aid to Africa: French and British Policies from the Cold War to the New Millennium. Burlinghton: Ashgate, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen W. Hook. National Interest and Foreign Aid. Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Olav Stokke. Western Middle Powers and Global Poverty: The Determinants of the Aid Policies of Canada, Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden. Uppsala: Scandinavian Institute of African Studies, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Donald Sassoon. “European Social Democracy and New Labour: Unity in Diversity? ” Political Quarterly 70 (1999): 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaus von Beyme. “Do Parties Matter? The Impact of Parties on the Key Decisions in the Political System.” Government and Opposition 19 (1984): 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibylle Scheipers, and Daniela Sicurelli. “Empowering Africa: Normative Power in EU-Africa Relations.” Journal of European Public Policy 15 (2008): 607–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick Holden. In Search of Structural Power: EU Aid Policy as a Global Political Instrument. Cornwall: Ashgate, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph S. Nye Jr. “Soft Power and American Foreign Policy.” Political Science Quarterly 119 (2004): 255–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan Keukeleire, and Jennifer MacNaughtan. The Foreign Policy of the European Union. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ian Manners. “Normative Power Europe: The international role of the EU.” In Paper presented at the European Union between the International and World Society: Biennial Conference of the European Union Studies Association, Madison, WI, USA, 31 May–2 June 2001.

- Ian Manners. “Normative power Europe: A contradiction in terms? ” Journal of Common Market Studies 40 (2002): 235–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ian Manners. “The normative ethics of the European Union.” International Affairs 84 (2008): 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the European Economic and Social Committee on the EU Strategy for Africa: Towards a Euro-African Pact to Accelerate Africa’s Development. Brussels: European Commission, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- “Treaty of Lisbon amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty establishing the European Community.” Official Journal of the European Union C306 (2007): 1–271.

- Martin Holland. The EU and the Global Development Agenda. London: Routledge, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament, European Council, and European Commission. “The European Consensus on Development.” Official Journal of the European Union C46 (2006): 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Millennium Development Goals Report 2011. New York: United Nations, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Richard Youngs. “Fusing security and development: Just another Euro-platitude? ” Journal of European Integration 30 (2008): 419–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennifer L. Erickson. “Market Imperative Meets Normative Power: Human Rights and European Arms Transfer Policy.” European Journal of International Relations 19 (2013): 209–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin Holland. The European Union and the Third World. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen R. Hurt. “Understanding EU Development Policy: History, Global Context and Self-Interest? ” Third World Quarterly 31 (2010): 159–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John J. Mearsheimer. The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York: Norton, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jan Zielonka. Paradoxes of European Foreign Policy. Boston: Kluwer Law International, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kenneth N. Waltz. Realism and International Politics. New York: Routledge, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kenneth N. Waltz. Theory of International Politics. Reading: Addison-Wesley, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan Stetter. “Cross-pillar politics: Functioning unity and institutional fragmentation of EU foreign policies.” Journal of European Public Policy 11 (2011): 720–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen R. Hurt. “Co-operation and coercion? The Cotonou Agreement between the European Union and EPA states and the end of the Lomé Convention.” Third World Quarterly 24 (2003): 161–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher Hill, and Michael Smith. International Relations and the European Union, 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stefan Cibian. “Book Review: In Search of Structural Power: EU Aid Policy as a Global Political Instrument, by Patrick Holden.” Journal of Common Market Studies 47 (2009): 1145–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelle Pace. “The Construction of EU Normative Power.” Journal of Common Market Studies 45 (2007): 1041–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary Farrell. “A Triumph of Realism over Idealism? Cooperation between the European Union and Africa.” Journal of European Integration 27 (2005): 263–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John Kotsopoulos. “The EU and Africa: Coming together at last? ” European Policy Centre. July 2007. Available online: http://bit.ly/1HYFEKM (accessed on 1 October 2014).

- Charlotte Bretherton, and John Vogler. The European Union as a Global Actor. New York: Routledge, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mirjam van Reisen, and Jaap Dijkstra. 2015-Watch: The EU’s Contribution to the Millennium Development Goals. Hague: Alliance2015, 2004, pp. 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- “Partnership agreement between the members of the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States of the one part, and the European Community and its Member States, of the other part, signed in Cotonou on 23 June 2000 - Protocols - Final Act - Declarations.” Official Journal of the European Communities L317 (2000): 3–286.

- Hein De Haas. “Turning the Tide? Why Development will not Stop Migration.” Development and Change 38 (2007): 819–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandra Lavenex, and Rahel Kunz. “The Migration-Development Nexus in EU External Relations.” Journal of European Integration 30 (2008): 439–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William Brown. “Reconsidering the Aid Relationship: International Relations and Social Development.” Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs 98 (2009): 285–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorm Rye Olsen. “Challenges to traditional policy options, opportunities for new choices: The Africa policy of the EU.” Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs 93 (2004): 425–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon Crawford. “The European Union and Democracy Promotion in Africa: The Case of Ghana.” European Journal of Development Research 17 (2005): 571–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrik Söderbaum, and Luk van Langenhove. The EU as a Global Player: The Politics of Interregionalism. Oxon: Routledge, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- William Easterly. “How the Millennium Development Goals are Unfair to Africa.” World Development 37 (2009): 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew Mold. EU Development Policy in a Changing World. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Adrian Flint. Trade, Poverty and the Environment: The EU, Cotonou and the African-Caribbean-Pacific Bloc. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Alan Matthews. “The European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy and Developing Countries: The Struggle for Coherence.” Journal of European Integration 30 (2008): 381–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrit Faber, and Jan Orbie. “EPAs between the EU and Africa: Beyond free trade? ” In Beyond Market Access for Economic Development: EU-Africa Relations in Transition. Edited by Gerrit Faber and Jan Orbie. London: Routledge, 2009, pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Paul Bowles. “Recipient Needs and Donor Interests in the Allocation of EEC Aid to Developing Countries.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue Canadienne d’études du Développement 10 (1989): 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Paul Dunne, and Nadir A. L. Mohammed. “Military Spending in Sub-Saharan Africa: Some Evidence for 1967–85.” Journal of Peace Research 32 (1995): 331–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukmani Gounder. “Empirical results of aid motivations: Australia’s bilateral aid program.” World Development 22 (1994): 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukasa Takamine. “Domestic Determinants of Japan’s China Aid Policy: The Changing Balance of Foreign Policymaking Power.” Japanese Studies 22 (2002): 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak Arvin, Joshua Rice, and Bruce Cater. “Are there country size and middle-income biases in the provision of EC multilateral foreign aid? ” European Journal of Development Research 13 (2001): 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Mak Arvin, and Torben Drewes. “Biases in the allocation of Canadian official development assistance.” Applied Economics Letters 5 (1998): 773–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarah Blodgett Bermeo, and David Leblang. “Foreign Interests: Immigration and the Political Economy of Foreign Aid.” In Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Political Economy Society, College Station, TX, USA, 13–14 November 2009.

- Christina J. Schneider, and Jennifer L. Tobin. “Interest Coalitions and Multilateral Aid: Is the EU Bad for Africa.” In Paper presented at the 3rd Annual Conference on the Political Economy of International Organizations, Washington, DC, USA, 28–30 January 2010.

- Jean-Claude Berthélemy. “Bilateral Donors’ Interest vs. Recipients’ Development Motives in Aid Allocation: Do All Donors Behave the Same? ” Review of Development Economics 10 (2006): 179–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alain Noël, and Jean-Philippe Thérien. “From domestic to international justice: The welfare state and foreign aid.” International Organization 49 (1995): 523–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joan Lacomba, and Alejandra Boni. “The Role of Emigration in Foreign Aid Policies: The Case of Spain and Morocco.” International Migration 46 (2008): 123–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Towards a More Development Friendly Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Brussels: European Commission, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gorm Rye Olsen. “Europe and Africa in the 1990s: European Policies towards a Poor Continent in an Era of Globalisation.” Global Society 15 (2001): 325–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter Boone. The Impact of Foreign Aid on Savings and Growth. London: London School of Economics and Political Science, Centre for Economic Performance, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Peter Boone. “Politics and the effectiveness of foreign aid.” European Economic Review 40 (1996): 289–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig Burnside, and David Dollar. “Aid, policies, and growth.” American Economic Review 90 (2000): 847–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kath A. Moser, David A. Leon, and Davidson R. Gwatkin. “How does progress towards the child mortality millennium development goal affect inequalities between the poorest and least poor? Analysis of Demographic and Health Survey data.” British Medical Journal 331 (2005): 1180–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federica Bicchi. “‘Our size fits all’: Normative power Europe and the Mediterranean.” Journal of European Public Policy 13 (2006): 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary Farrell. “From EU model to external policy? Promoting regional integration in the rest of the world.” In Making History: European Integration and Institutional Change at Fifty. Edited by Sophie Meunier and Kathleen R. McNamara. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2007, pp. 299–315. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen R. Hurt. “The European Union’s External Relations with Africa after the Cold War.” In Africa in International Politics: External Involvement on the Continent. Edited by Ian Taylor and Paul Williams. London: Routledge, 2004, pp. 155–73. [Google Scholar]

- Frank Schimmelfennig. “Europeanization beyond Europe.” Living Reviews in European Governance 7 (2007): 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro C. Vicente. “Does oil corrupt? Evidence from a natural experiment in West Africa.” Journal of Development Economics 92 (2010): 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David E. McNabb. Research Methods for Political Science: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. New York: M.E. Sharp, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- R. Burke Johnson, and Larry Christensen. Educational Research: Quantitative, Qualitative and Mixed Approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Larry D. Schroeder, David L. Sjoquist, and Paula E. Stephan. Understanding Regression Analysis: An Introductory Guide. London: Sage, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- “All definitions are from the website of the World Bank.” Available online: http://www.worldbank.org (accessed on 1 October 2014).

- Daniel Kaufmann, Aart Kraay, and Massimo Mastruzzi. “Governance Matters III: Governance Indicators for 1996, 1998, 2000, and 2002.” World Bank Economic Review 18 (2004): 253–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrian E. Raftery. “Bayesian model selection in social research.” Sociological Methodology 25 (1995): 111–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In the model excluding DR Congo and Ethiopia, FDI and CO2 emissions are now statistically significant predictors. For FDI the contribution remains minimal with a coefficient of 0 while for CO2 emissions the coefficient is now 115.8 (95% CI 2.45-229.14). For the first and second model Akaike’s Information Criterion is 11.89 and 11.37 respectively.

- Rainer Thiele, Peter Nunnenkamp, and Axel Dreher. “Do Donors Target Aid in Line with the Millennium Development Goals? A Sector Perspective of Aid Allocation.” Review of World Economics Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv 143 (2007): 596–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sophia Rabe-Hesketh, and Anders Skrondal. Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling Using Stata, 3rd ed. College Station: Stata Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich Kohler, and Frauke Kreuter. Data Analysis Using Stata. College Station: Stata Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- William H. Greene. Econometric Analysis. New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher Dougherty. Introduction to Econometrics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bountagkidis, G.K.; Fragkos, K.C.; Frangos, C.C. EU Development Aid towards Sub-Saharan Africa: Exploring the Normative Principle. Soc. Sci. 2015, 4, 85-116. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4010085

Bountagkidis GK, Fragkos KC, Frangos CC. EU Development Aid towards Sub-Saharan Africa: Exploring the Normative Principle. Social Sciences. 2015; 4(1):85-116. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4010085

Chicago/Turabian StyleBountagkidis, Georgios K., Konstantinos C. Fragkos, and Christos C. Frangos. 2015. "EU Development Aid towards Sub-Saharan Africa: Exploring the Normative Principle" Social Sciences 4, no. 1: 85-116. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4010085

APA StyleBountagkidis, G. K., Fragkos, K. C., & Frangos, C. C. (2015). EU Development Aid towards Sub-Saharan Africa: Exploring the Normative Principle. Social Sciences, 4(1), 85-116. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4010085