Practicing from Theory: Thinking and Knowing to “Do” Child Protection Work

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Background

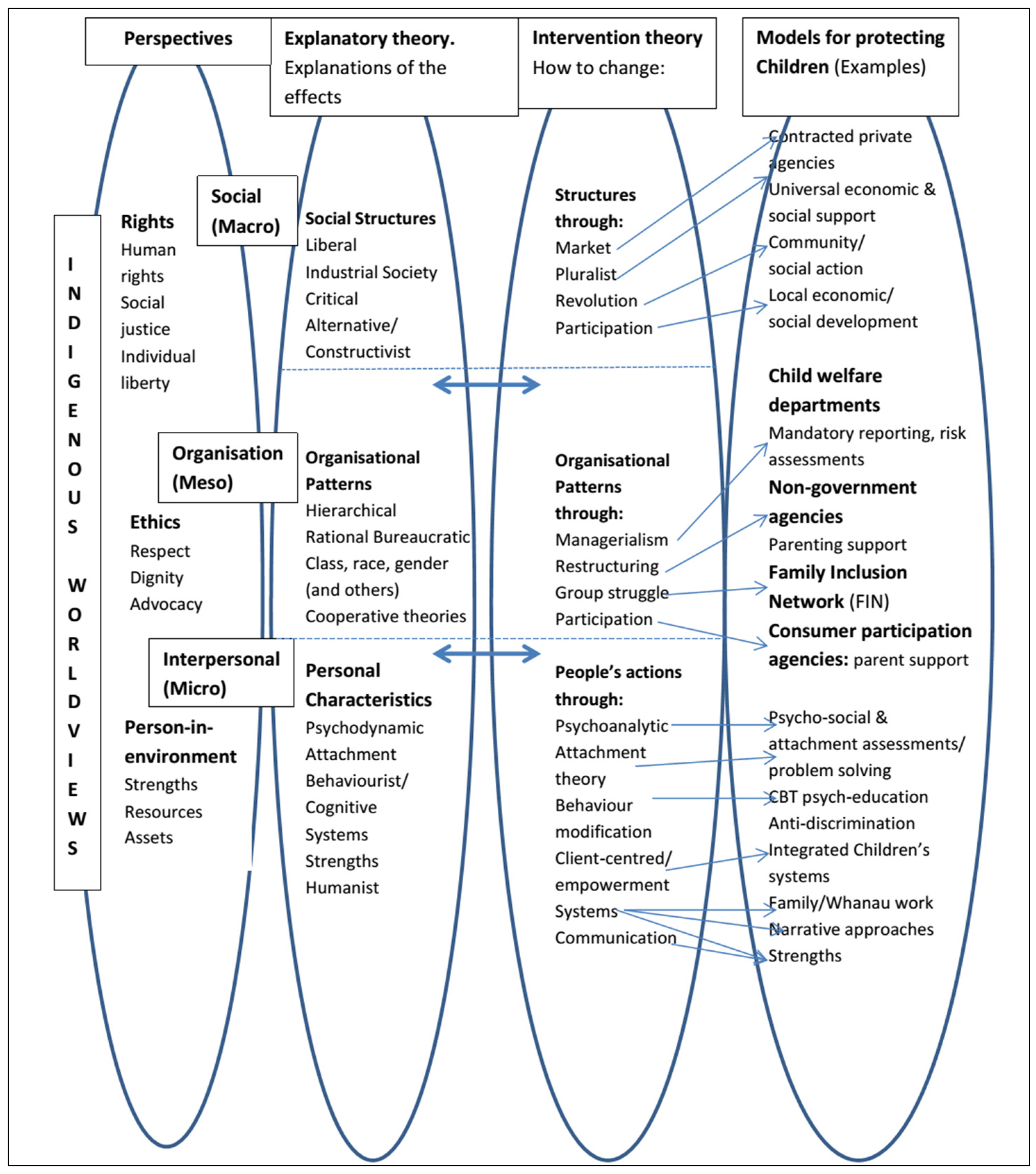

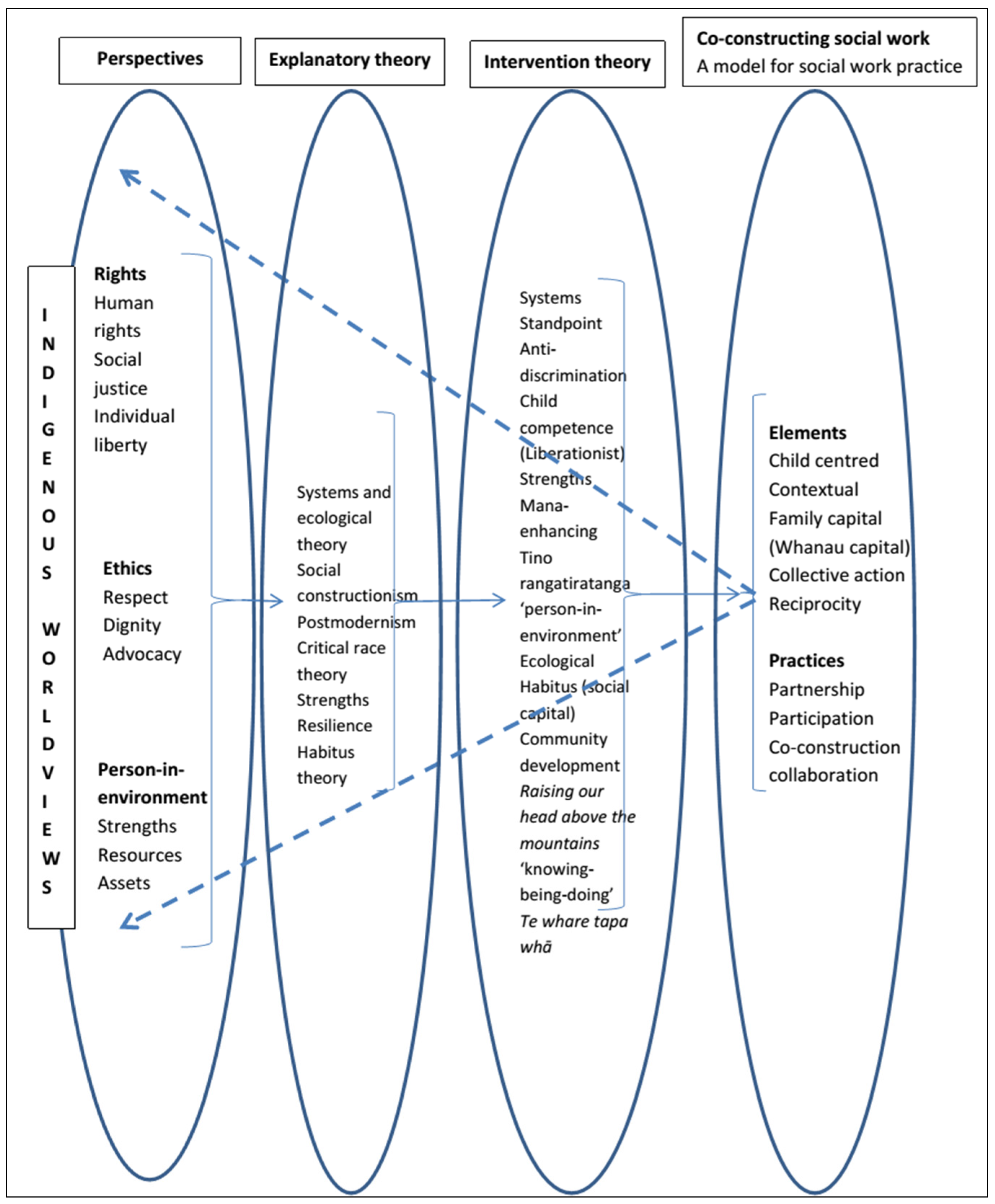

2. A Model for Practice

| Key Elements | Description/Skills and Process | Theoretical Perspective/Knowledge |

|---|---|---|

| Child centred | Seeking, listening to and acting on the child’s definition of his/her daily life | Children as competent agents |

| Resilience | ||

| Human/children’s rights | ||

| Contextual | Situatedness (time, place, history, culture) | Social constructivism |

| Symbolic interaction | ||

| Family capital | Family knowledge, history, capability, contacts | Social capital |

| Social network | ||

| Strengths | ||

| Family definition | ||

| Collective action | The whole is more than the sum of the parts | Power |

| The whole has greater longevity | Community development | |

| Participative democracy | ||

| Distributed leadership | Social justice | |

| Reciprocity | The family as theorist | Learning |

| Shared responsibility | Anti-oppression | |

| Trustworthiness | Cross-cultural |

3. A Theoretical Framework

3.1. Worldviews for Community Based Child Protection Work

3.1.1. Rights

3.1.2. Ethics

Members actively promote the rights of Tangata Whenua to utilise Tangata Whenua social work models of practice and ensure the protection of the integrity of Tangata Whenua in a manner which is culturally appropriate.

3.1.3. Person-in-Environment

3.2. A Rights, Ethics and Person-in-Environment World View for Child Protection Practice

4. Explanatory Theory for Child Protection Practice

5. Intervention Theories, or Theories for Child Protection Practice

6. Model to Theory: Co-Constructing Social Work

- What is your puku (stomach) saying to you? (Physical response).

- What is your ngakau (heart) saying to you? How have you connected with them and what they are saying and doing? (Felt response).

- What is your wairua (spirit) saying to you? (Sensed response).

- What does Te Ao Maori/Pakeha matauranga (mind) theory say to you? (Thought response).

- What are the whanaungatanga (family making) issues that resonate here? (Relational response).

- What kind of fabric is being woven? It includes distinctiveness that comes from a number of variants in this cultural context. (Integration response) ([69], p. 26).

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Charles Waldegrave. “Contrasting national jurisdictional and welfare responses to violence to children.” Social Policy Journal of New Zealand 27 (2006): 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- John Devaney, and Trevor Spratt. “Child abuse as a complex and wicked problem: Reflecting on policy developments in the United Kingdom in working with children and families with multiple problems.” Children and Youth Services Review 31 (2009): 635–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susan Young, Margaret McKenzie, Cecilie Omre, and Liv Schjelderup. “The rights of the child enabling community development to contribute to a valid social work practice with children at risk.” European Journal of Social Work 15 (2012): 169–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susan Young, Margaret McKenzie, Cecilie Omre, Liv Schjelderup, and Shayne Walker. “What can we do to bring the sparkle back into this childs’ eyes? Child Rights/Community Development Principles: Key elements for a strengths based child protection practice.” Child Care in Practice 20 (2014): 135–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susan Young, Joanna Zubrzycki, Dawn Bessarab, Sue Green, Victoria Jones, and Katrina Stratton. “Getting it Right: Creating partnerships for change: Developing a framework for integrating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges in Australian social work education.” Journal of Ethnic And Cultural Diversity in Social Work 22 (2013): 179–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayla J. Russell. Landscape: Perceptions of Kai Tahu 2000. Dunedin: University of Otago, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Anaru Eketone, and Walker Shayne. “Kaupapa Social Work Research.” In Decolonizing Social Work. Edited by Gray Mel, John Coates, Michael Yellowbird and Tiani Hetherington. London: Ashgate Publishing, 2013, pp. 259–70. [Google Scholar]

- Moana Eruera. “He Korari, He kete, He Korero.” Te Komako, Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work 24 (2012): 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Moana Eruera. “An Indigenous Social Work Experience in Aotearoa New Zealand.” In Becoming a Social Worker: Global Narratives, 2nd ed. London & New York: Routledge, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ling How Kee, Jennifer Martin, and Ow Rosaleen. Cross-Cultural Social Work. South Yarra: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tracey Mafile’o. “Pasifikan social work theory.” Social Work Review 13 (2001): 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Taina Whakaatere Pohatu. “Takepu: Principled approaches to health relationships.” In Traditional Knowledge Conference 2008: Te Tatau Pounamu: The Greenstone Door. Hamilton: Te Wananga o Aotearoa, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Leland Ruwhiu. “Home fires burn so brightly with theoretical flames.” Te Komako Social Work Review 7 (1995): 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Leland Ruwhiu. “Bicultural issues in Aotearoa New Zealand social work.” In New Zealand Social Work: Contexts and Practice. Edited by Marie Connolly. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 54–71. [Google Scholar]

- Leland Ruwhiu, Witi Ashby, Heta Erueti, Allan Halliday, Hemi Horne, and Phil Paikea. A Mana Tane Echo of Hope: Dispelling the Illusion of Whānau Violence–Taitokerau Tāne Māori Speak Out. Amokura: Family Violence Prevention Consortium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Leland Ruwhiu, and Moana Eruera. “Ngā karangaranga maha o te ngākau o ngā tūpuna. Tiaki Mokopuna. Ancestral heartfelt echoes of care for children.” In Indigenous Knowledges: Resurgence, Implementation and Collaboration. Winnipeg: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shayne Walker. “The teaching of Maori social work practice and theory to a predominantly Pakeha audience.” Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work 24 (2012): 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Shayne Walker. “Tamariki and Whanau in the Milieu of Child Protection Decision-Making.” In Hui Poutama Maori Research Symposium Ka Haere Whakamua, Ki Titiro Whakamuri. New Zealand: University of Otago, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shayne Walker. “Seeds of illumination in a sometimes dry landscape.” Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work 24 (2012): 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Susan C. R. Diamond. “The State as parent: Metamorphosis from ‘wire-monkey’ parent to benefactor? ” In Social Work and Social Policy. Perth: University of Western Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Uschi Bay. Social Work Practice: A Conceptual Framework. Melbourne: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Association of Social Workers. Code of Ethics. Canberra: Australian Association of Social Workers, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick Butler. “Trainee social workers taught too much theory, says report.” The Guardian, 2014 13 February, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Kurt Lewin, and Dorwin Cartwright. Field Theory in Social Science: Selected Theoretical Papers by Kurt Lewin. London: Tavistock, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Maarten Vansteenkiste, and Kennon M. Sheldon. “There’s nothing more practical than a good theory: Integrating motivational interviewing and self-determination theory.” British Journal of Clinical Psychology 45 (2006): 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert J. Greene, and Mo Yee Lee. Solution-Oriented Social Work Practice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pat Shannon, and Susan Young. Solving Social Problems: Southern Perspectives. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press, 2004, p. 319. [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm Payne. Modern Social Work Theory, 2nd ed. Houndmills: Macmillan, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Karen Healy. Social Work Theories in Context: Creating Frameworks for Practice. Houndsmill: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005, p. 238. [Google Scholar]

- David Howe. An Introduction to Social Work Theory: Making Sense in Practice (Community Care Practice Handbooks). Aldershot: Wildwood House, 1987, vol. 24, p. 182. [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm Payne. Modern Social Work Theory, 3rd ed. Houndsmill: Macmillan, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Social Workers (NASW). Social Justice. Washington, D.C.: NASW Pressroom, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm Payne. “What’s so special about social work and social justice? ” The Guardian, 10 July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- John Rawls. A Theory of Justice. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- John Rawls. Justice as Fairness. A Restatement. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Emmanuel Levinas. Entre Nous: Thinking-of-the-Other. London: The Athlone Press, 1998, p. 256. [Google Scholar]

- Jim Ife. Human Rights and Social Work: Towards Rights-Based Practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 228. [Google Scholar]

- Richard Hugman. New Approaches in Ethics for the Caring Professions. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sarah Banks. Ethics and Values in Social Work. Houndmills: Palgrave, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Annie Pullen-Sansfaçon, and Stephen Cowden. The Ethical Foundations of Social Work. Harrow: Pearson, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Simon Critchley. Infinitely Demanding: Ethics of Commitment, Politics of Resistance. London: Verso, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Aotearoa New Zealand Association of Social Workers (ANZASW). Code of Ethics. Christchurch: ANZASW, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Henare Arekatera Tate. “Towards Some Foundations of a Systematic Maori Theology (He Tirohanga Anganui Ki Etahi Kaupapa Hohono Mo Te Whakapono Maori).” Ph.D. Thesis, Melbourne College of Divinity, Melbourne, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Michael Ungar. “A Deeper, More Social Ecological Social Work Practice.” Social Service Review 76 (2002): 480–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilary Weaver, and Elaine Congress. “Indigenous People in a Landscape of Risk: Teaching Social Work Students About Socially Just Social Work Responses.” Journal of Ethnic And Cultural Diversity in Social Work 18 (2009): 166–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urie Bronfenbrenner, and Stephen J. Ceci. “Nature-Nuture Reconceptualized in Developmental Perspective: A Bioecological Model.” Psychological Review 101 (1994): 568–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorothy Scott. “Embracing what works: Building communities that strengthen families.” Children Australia 25 (2000): 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Elaine P. Congress. “Cultural and Ethical Issues in Working with Culturally Diverse Patients and Their Families.” Social Work in Health Care 39 (2005): 249–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason Durie. Whaiora: Maori Health Development 1998. Auckland: Oxford University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kathleen Kufeldt, and Brad McKenzie. “The policy, practice and research connection: Are we there yet? ” In Child Welfare: Connecting Research, Policy and Practice. Edited by Kathleen Kufeldt and Brad McKenzie. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2011, pp. 569–88. [Google Scholar]

- J. Fraser Mustard. “Experience-based brain development: Scientific underpinnings of the importance of early child development in a global world.” Paediatrics & Child Health 11 (2006): 571–72. [Google Scholar]

- Jatinder Kaur. Cultural Diversity and Child Protection. A Review of the Australian Research on the Needs of Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) and Refugee Children and Families. Queensland: Diversity Consultants, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Claudia Bernard, and Anna Gupta. “Black African Children and the Child Protection System.” British Journal of Social Work 38 (2008): 476–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashok Chand. “The over-representation of Black children in the child protection system: Possible causes, consequences and solutions.” Child & Family Social Work 5 (2000): 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Nancy A. Rodenborg. “Services to African American Children in Poverty: Institutional Discriminiation in Child Welfare? ” Journal of Poverty 8 (2004): 109–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robyn Maree Miller. Best Interests Principles: A Conceptual Overview. Melbourne: Department of Human Services, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ferol E. Mennen, Kihyun Kim, Jina Sang, and Penelope K. Trickett. “Child Neglect: Definition and Identification of Youth’s Experiences in Official Reports of Maltreatment.” Child Abuse & Neglect 34 (2010): 647–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kenneth J. Gergen. Social Construction in Context. London: SAGE, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nigel Parton, and Patrick O’Byrne. Constructive Social Work: Towards A New Practice. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2000, p. 246. [Google Scholar]

- Kenneth J. Gergen. An Invitation to Social Construction. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Liz Davies, and Nora Duckett. Proactive Child Protection in Social Work. Exeter: Learning Matters, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Harry Ferguson. Child Protection Practice. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Marie Connolly, and Kate Morris. Understanding Child and Family Welfare: Statutory Responses to Children at Risk. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- David Howe. Attachment Theory for Social Work Practice. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- David Howe. Child Abuse and Neglect: Attachment, Development, and Intervention. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Violet Bacon. “Yarning and Listening: Yarning and Learning Through Stories.” In Our Voices: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Work. Edited by Bindi Bennett, Sue Green, Stephanie Gilbert and Bessarab Dawn. Melbourne: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013, pp. 136–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Berg Insoo, and Susan Kelly. Building Solutions in Child Protective Services. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Robert L. Lonne, Nigel Parton, Jane Thomson, and Harries Maria. Reforming Child Protection. London: Routledge, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mason Durie. Maori Concepts of Wellbeing. Intervening with Maori Children, Young People & Families. Invercargill: Compass Seminars, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy L. Robinson. “The intersections of dominant discourses across race, gender and other identities.” Journal of Counselling and Development 77 (1999): 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulo Freire. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1972, p. 153. [Google Scholar]

- Susan Young. “Social work theory and practice: The invisibility of whiteness.” In Whitening Race: Essays in Social and Cultural Criticism. Edited by Aileen Moreton-Robinson. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2004, pp. 104–18. [Google Scholar]

- 1While WA is not an autonomous nation, it is the jurisdiction within Australia with responsibility for child protection for that State under the country’s federal system.

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Young, S.; McKenzie, M.; Omre, C.; Schjelderup, L.; Walker, S. Practicing from Theory: Thinking and Knowing to “Do” Child Protection Work. Soc. Sci. 2014, 3, 893-915. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci3040893

Young S, McKenzie M, Omre C, Schjelderup L, Walker S. Practicing from Theory: Thinking and Knowing to “Do” Child Protection Work. Social Sciences. 2014; 3(4):893-915. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci3040893

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoung, Susan, Margaret McKenzie, Cecilie Omre, Liv Schjelderup, and Shayne Walker. 2014. "Practicing from Theory: Thinking and Knowing to “Do” Child Protection Work" Social Sciences 3, no. 4: 893-915. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci3040893

APA StyleYoung, S., McKenzie, M., Omre, C., Schjelderup, L., & Walker, S. (2014). Practicing from Theory: Thinking and Knowing to “Do” Child Protection Work. Social Sciences, 3(4), 893-915. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci3040893