2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This study involved 50 frontline professionals. The sample included 44 female and 6 male participants, representing a range of racial and ethnic identities (39 white; 1 African American; 5 Hispanic; 2 multiracial). Inclusion criteria mandated that participants be at least 18 years old, possess a minimum of five years of experience working with CSA victims and/or sexually reactive youth, and demonstrate English language fluency. Of the participants, 46 (92%) were based in the United States, while others were in the United Kingdom, Canada, and New Zealand. Seventy-two percent held master’s degrees or higher. On average, participants were 45 years old (SD = 12.46) and had 7.5 years of experience in their current roles (range: 5–37 years; SD = 7.15). The sample included professionals from diverse backgrounds: forensic interviewers (38%), healthcare professionals (22%), therapists (22%), and law enforcement officers and social workers (18%). One forensic interviewer had also worked with juvenile sex offenders, noting that many of these children had previously been abused. Average religiosity among participants was reported as moderate (M = 4.65, SD = 2.131).

2.2. Recruitment

Potential participants were recruited through email outreach to professionals in the field (counselors, advocates, and forensic interviewers) and to Child Advocacy Centers (CACs). Several hundred outreach emails were sent until the goal of 50 interviewees was achieved, with over 100 individuals completing a screening questionnaire. Eligible participants received follow-up emails containing project details, a consent form, and an interview schedule. Not all participants responded, and some scheduled interviews were missed due to last-minute emergencies, often work-related.

2.3. Individual Interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted via Zoom, lasting between one and two hours (M = 1.5 h), and included one or more researchers. Participants completed a post-interview demographic survey and were asked to suggest additional potential participants. Each participant received a $50 (or equivalent) digital gift card as compensation. Interviews were conducted in the fall of 2021 through the winter of 2022.

2.4. Focus Groups

Following the coding of individual interviews and the development of a conceptual model, participants were re-contacted for virtual focus groups to validate the model. During these sessions, researchers presented findings and the model, allowing for participant feedback. A total of eight focus groups were conducted. Participants were compensated with a $50 (or equivalent) digital gift card. Focus groups were held across the spring of 2022.

2.5. Measures

A semi-structured interview format was used, featuring standardized stem questions and tailored follow-up inquiries. The interviews addressed participants’ backgrounds and experiences in the field, perceived patterns of CSA, views on potential connections between pornography and CSA, and suggestions for prevention and response strategies. Participants’ self-care strategies and personal views on pornography were also discussed but are not analyzed in this paper.

2.6. Analytic Approach

All interviews and focus group responses were recorded and transcribed. To promote intercoder reliability (see

O’Connor and Joffe 2020), a subset of the research team coded the same five interviews and compared codes and results across the team. Broad patterns and agreements were identified and refined, and discrepancies were addressed and resolved to begin building a codebook through open coding (

Charmaz 2006). Researchers collaborated to refine the codebook and coded all interviews using NVivo 13 software, meeting regularly to discuss and revise codes throughout the coding process. Subsequently, axial coding (ibid.) was performed to categorize and refine the original codes through regular full-team meetings, leading to the development of the conceptual model, which was further validated through focus groups with participants to ensure opportunities for feedback and co-construction of the knowledge gleaned from this project.

2.7. Researchers: Positionality and Reflexivity

Members of the research team are mindful that our identities, structural locations, and previous experiences and assumptions can influence our approach(es) to science. The research team consisted of four professors and two graduate students representing a range of disciplines, including media studies (n = 1), sociology (n = 4), and psychology (n = 1). With respect to gender, at the time of the drafting of this paper, four of the authors identified as women, one identified as a man, and one identified as non-binary. Regarding race and ethnicity, four identified as white and non-Hispanic, one identified as white and Hispanic, and one identified as Asian. With respect to nationality, four were citizens of the United States, and two were dual citizens (Argentina and the United States, Taiwan and the United States).

The research received funding support from a non-profit organization that takes a science-based but explicit position that pornography is harmful to young people.

1 Although our research team takes a firm position that child sexual abuse is harmful, and although we have engaged in multiple research projects addressing patterns and associations related to pornography exposure and consumption, our commitment is not to advance the mission of the funding organization, but to do justice to the research process and, notably, to our participants. The funding source provided no direction, oversight, or influence over any part of the research process.

In an effort to “get the story right” (see

Ezzell 2013), we sought to engage a team-based, iterative, reflexive praxis (see

Rankl et al. 2021) from the outset of the project. This included multiple discussions to unpack and interrogate the personal, political, disciplinary, and methodological assumptions and expectations held across the research team; frequent check-ins and debriefs following interviews and throughout the data analysis process (including the creation and application of the codebook, described above); and focus group check-ins with participants, followed by subsequent team debriefs. The analysis presented here is fully the work of the research team members, co-created with our participants.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Patterns in CSA Perpetration and Victimization

This research examined frontline providers’ perceptions of possible links between CSA and pornography. Participants’ accounts largely supported existing literature. For example, victims were mostly (but not always) female, while adult perpetrators were mostly (but not always) male. Participants noted that social norms might discourage boys from seeking help, making it likely that more male victims exist than are reported. They also indicated that perpetrators are often known to the victim, including family members, acquaintances, or community figures, with many referencing variations of “mom’s new romantic partner” or “mom’s new husband.” Abuse involving strangers usually took place online (e.g., video games, social media) and included image-based crimes such as extorting self-produced nude images or videos from victims; however, several participants pointed out that these exploitative situations sometimes escalated to contact abuse.

Regarding race and socioeconomic status, participants observed that both victims and perpetrators largely mirrored the demographics of their communities (participants were majority white-identified but served a range of different communities in different contexts). In instances of over- or under-representation of specific groups, interviewees provided various explanations. Some suggested that overrepresentation, particularly among marginalized racial groups or economically vulnerable families, may stem from systemic prejudices or their involvement with government systems, resulting in heightened monitoring or surveillance of these individuals and families. Conversely, participants noted that wealth or power could shield certain perpetrators from being reported. Additionally, several participants mentioned an increase in reports of abuse involving LGBTQ+ children, though they were uncertain whether this reflected a rise in victimization or an increase in children openly identifying as LGBTQ+. Notably, participants also reported a rise in child perpetrators—often referred to as “initiators”—typically manifesting as children exhibiting problematic sexual behavior by “acting out” on peers of similar age.

3.2. Conceptual Overview of the Model

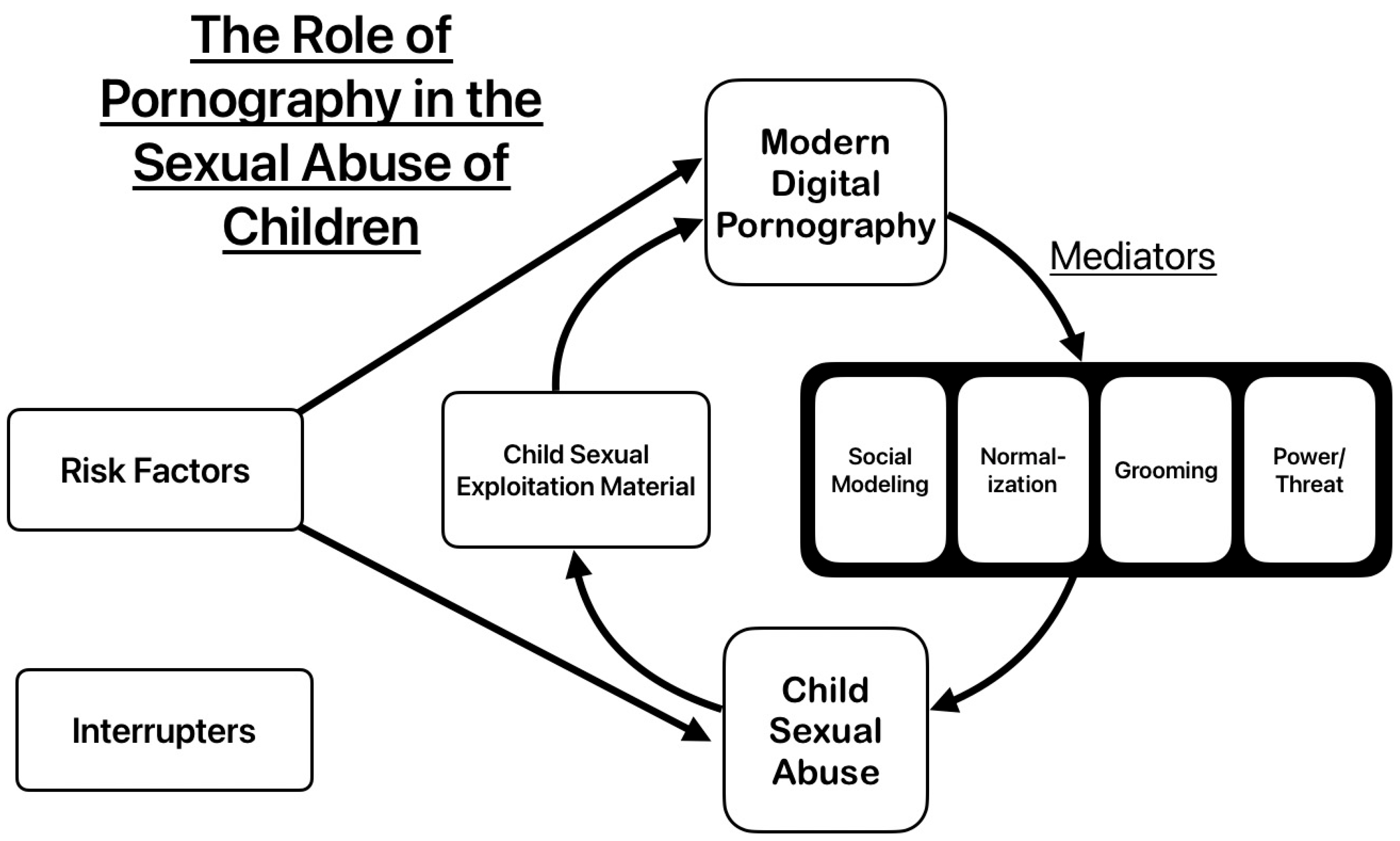

Participants consistently identified perceived links between CSA and pornography, although observed connections varied. Through coding and analysis, we created a conceptual model that captures their different responses (

Figure 1). The model depicts cyclical and overlapping relationships between risk factors, pornography, potential “interrupters,” and CSA.

The model, drawing on frontline workers’ accounts, explores how exposure to digital pornography may begin a cycle linking pornography and CSA, situating pornography as a mediated zone of violence in and through which harm can be encountered, documented, normalized, negotiated, processed, and intensified. For example, children with strained parental relationships or inadequate supervision may be more likely to encounter digital pornography, which may increase the risk of CSA through various mediators. With easy access to digital pornography and limited or inadequate sexual education, pornography has become a primary source of sexual knowledge. Exposure can normalize aggressive behaviors, raising risks of victimization and perpetration. Additionally, pornography may be used by predators for grooming or (intentionally or unintentionally) by children, leading to subsequent abuse or sexual acting out. It can also be used as a tool of coercion, silencing victims through fear of exposure (as seen in “revenge porn”). This cycle may continue through the digital documentation of abuse (the creation of CSAM, which can be shared), or victims might turn to pornography consumption post-abuse as a coping mechanism.

3.3. Risk Factors

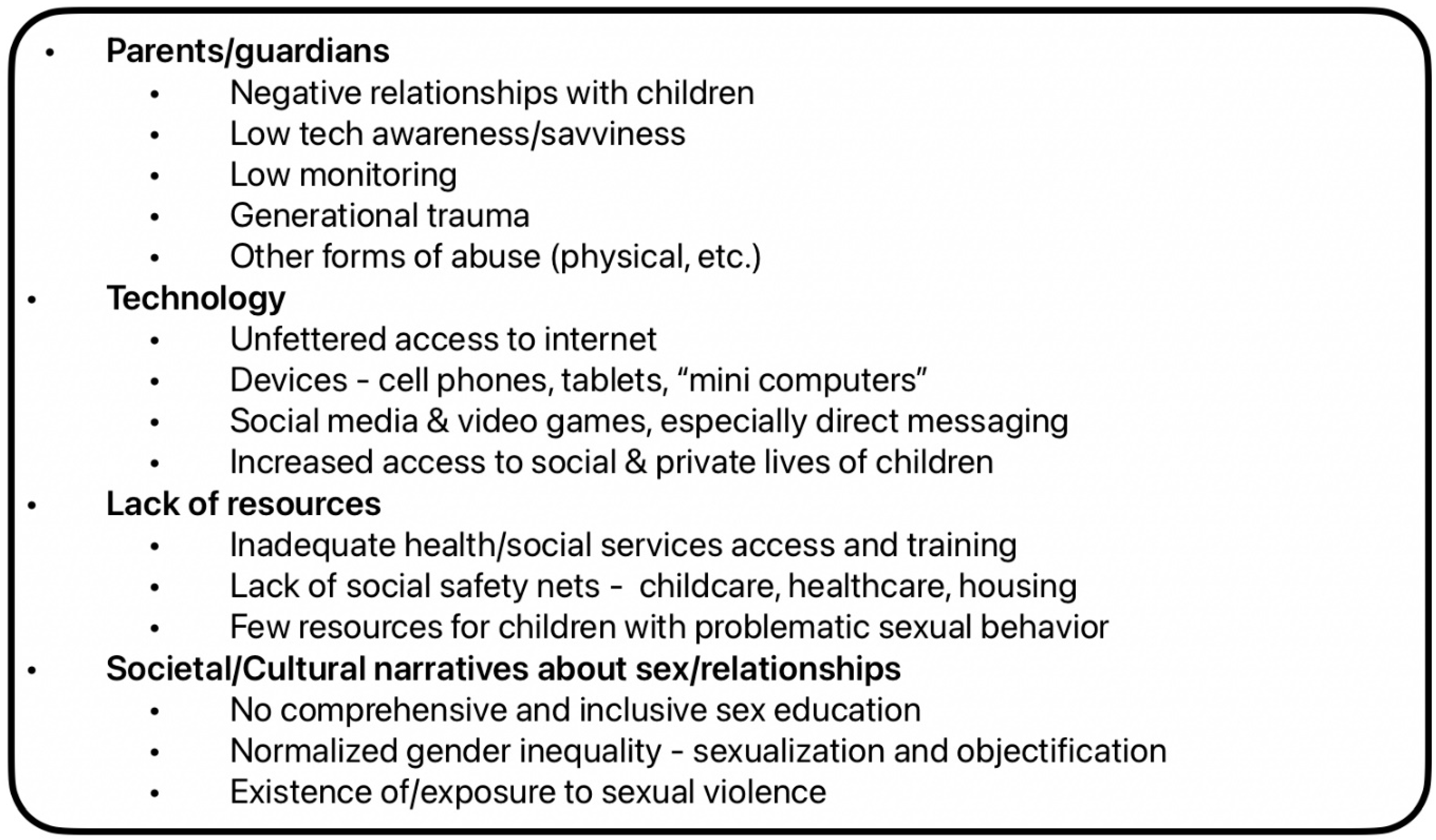

Participants described a range of factors that can place youth at increased risk of being exposed to pornography and of experiencing CSA (

Figure 2). Responses were categorized into the following categories: parents/guardians; technology; lack of resources; and, societal/cultural narratives around sex/relationships.

3.3.1. Parents/Guardians

Participants identified various parental and guardian factors they felt could elevate youth risk. First, negative guardian/child relationships could contribute to a lack of trust and, by extension, delayed disclosure of abuse or exposure to pornography. Even more, several participants highlighted the harmful impact when guardians disbelieve children. Jordyn, a Pediatric Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE), put it simply, “I have had a few parents who don’t believe their children, … which is really challenging.” Lack of belief could contribute to a lack of needed support to facilitate healing and trust, let alone the support needed to navigate the legal system.

Interviewees also noted that poor boundaries can exacerbate risks. Claire, an Executive Director of a CAC, explained, “Parents won’t take the phone away … because they’re afraid they’re going to be a [air quotes] ‘bad parent’ … [Y]ou gotta be a parent!” This example connects the guardian role to other risk factors such as low tech-savviness. The rapid evolution of technology and generational gaps in knowledge can contribute to low monitoring. Corey, a therapist, said, “… you’re expecting caregivers who have not lived with technology like this their whole lives to compete with what would have been the IT rock stars 10 years ago in their kids.” In this context, even attempts at setting boundaries could fail. Indeed, even the most strident filters for explicit content are not foolproof. Anna, an educator and advocate against internet child exploitation, reflected on the ways that low digital literacy and low monitoring could contribute to inadvertent exposure to pornography. She described a situation in which young children are looking for cartoons on popular sites like YouTube. Although the sought-after video may be appropriate, suggested videos on the site may not be: “The parent gets up and they walk around and … the [suggested content] is hardcore, triple-X porn.” Guardians’ struggles with substance use and mental health issues can also pose risks, as they can engender a lack of stability and structure within the home. Maryanne, a nurse within a CAC, noted, “…that just predisposes [children] to lack of supervision, people coming and going in the homes.” Participants also noted that other forms of abuse, such as physical violence or neglect, often coincide with CSA.

Finally, participants pointed out that generational trauma within families can increase vulnerability. Some spoke of a context of abuse in which one family member was the abuser for multiple generations of victims. Others described the compounding harm experienced when guardians who carry unresolved trauma from their own childhood abuse are faced with caring for a child who has experienced something similar.

3.3.2. Technology

One of the most prominent risk factors highlighted in our interviews focused on children’s un- or under-restricted access to the internet via devices such as gaming consoles, tablets, and smartphones, often without guardians’ awareness. Marie, a Forensic Interviewer, noted the many Internet-capable devices to which children have access. And Natalie, a mental health clinician, echoed other participants equating modern cell phones with Internet-equipped “mini-computers … that you hold in your hand.” Beyond this, several participants focused specifically on the importance of social media, as Nicholas, a Forensic Interviewer, pointed out: “Whenever phones came out with the Internet … that also allowed perpetrators to have contact with kids … through Snapchat, … Facebook, things like that.” Angela, a Pediatric SANE, agreed: “I can’t tell you the number of kids I’ve taken care of who have met up with [a perpetrator] from social media.”

In addition to social media platforms, our participants highlighted team-based video games as an avenue for perpetrators to access and exploit children. Julia, a Forensic Evaluation Clinician, reflected on the case of a 12-year-old boy who connected with a stranger through the game, Fortnite. The stranger offered to send the boy V-Bucks (in-game currency) and followed that by sending the boy pornographic videos, unsolicited. Over time, the boy began requesting the videos, but the stranger escalated the contact: “He would be, like, ‘Well, send me [nude] pictures of you. And, also, if you want, I’ll send you more V-Bucks, also, to make it worth your while.’” Digital access to children can be used by perpetrators in the service of grooming and sexual exploitation, including not only the solicitation of nude images from the children but also the sending of nude images of adults. Courtney, a CAC consultant, highlighted the normalization of such behaviors: “I cannot tell you the number of kids who are, like, ‘Oh, yes, sometimes people will send you a dick pic.’” Additionally, perpetrators may build trust through online contact before exploiting children in person, as Carly, a SANE, explained: “So, they might start asking for naked photos … until they meet these kids in person and then sexually assault them.” Courtney noted that although this was “not okay” and a clear example of sexual abuse for “some adult to do that to an 8- or 10- or 12-year-old,” this behavior was normalized to the point that it was “just par for the course for so many kids” with social media accounts.

Our participants primarily discussed perpetrators who were openly adults targeting children online, but they also pointed to the problem of adults pretending to be children. Carly, a SANE, described a way this played out in her practice: “So, [the adult posing as a child] might start asking for naked photos … to sort of normalize the sexual abuse and exploitation until they get to a point of where they meet these kids in person and then sexually assault them.” Although less common in her experience, Carly also noted seeing teenagers doing something similar to same-aged peers, where a trusted relationship would be built before the teenage perpetrator would meet up with and sexually assault the victim.

3.3.3. Lack of Resources

Participants identified systemic resource deficiencies as significant risk factors, affecting both families and professionals. For instance, several lamented a lack of social and health services, education, and training for professionals in the field, in addition to a lack of comfort among colleagues when screening for exposure to/consumption of pornography. They also discussed harmful stereotypes they heard from colleagues related to issues such as male victims or sexually reactive children. For example, Maryanne, a Pediatric Nurse Practitioner, discussed hearing an investigator discuss such children, “as bad kids, problematic kids, promiscuous kids,” pointing out that, “you can’t really be promiscuous at the age of 7- and 9-years old.” Such reductive labeling of children, she pointed out, hampers support and healing.

Participants highlighted that inadequate training and limited access to social services, such as affordable housing and childcare, also increase risks for children. This can be particularly concerning when perpetrators exploit family vulnerabilities. Participants noted that the perpetrator was often the main financial provider, which the perpetrator could manipulate to exert control. Linda, a therapist, pointed out that perpetrators can take advantage of “a childcare crisis we have.” She noted that society undervalues teachers and poorly compensates childcare workers, resulting in families struggling to find high-quality care. This lack of proper supervision may lead to situations where childcare providers may not monitor children closely or might have acquaintances over, potentially putting children at risk. These systemic inequalities and lack of support can significantly heighten the risks of child sexual abuse (CSA).

Several participants worked directly with children exhibiting problematic sexual behavior, sexual conduct that is developmentally inappropriate or harmful to others. In addition to the structural inequalities and limited resources previously mentioned, these participants emphasized the damaging tendency of the justice system to pathologize sexually reactive children in order to access needed resources. Claire, a CAC Director, expressed her frustration: “We have to charge that child in DJJ [the Department of Juvenile Justice] in order to get treatment, which is so screwed up.” Corey, a therapist, echoed her concerns, lamenting that within the justice system, “instead of remembering that they are a kid … we’re putting a label [like ‘perpetrator’ or ‘sex offender’] on.” The participants’ comments underscored how the scarcity of supportive resources and the limited access to available services can heighten children’s risks of exposure to both pornography and child sexual abuse (CSA).

3.3.4. Social Narratives Around Sex

Participants emphasized that a lack of education about online behavior, pornography, and child sexual exploitation can increase children’s vulnerability to pornography exposure and child sexual abuse (CSA). Bonnie, a CAC Director and Forensic Interviewer, remarked, “A lot of folks [are] saying, ‘If we talk about this to our children, it is going to make them want to engage.’ No, it’s not. It’s the opposite.” Participants observed that many guardians shy away from discussing sex with their children, leading to a knowledge gap that children may fill through internet searches and potentially harmful interactions with predators. Corey, a therapist, explained, “[W]hen kids have questions and we’re in a society that feels uncomfortable at answering those questions, then they Google.… And unfortunately, I think when you Google ‘sex’ you don’t get, like, a nice, kid-friendly WebMD article.” Donna, a CAC Coordinator, agreed, stating, “I think that if kids were more educated and more comfortable having conversations with adults … that maybe […] they would be able to protect themselves better online.” Participants concluded that cultural norms that restrict knowledge and open dialogue are not contributing to children’s safety.

Participants also highlighted that gender inequality and patriarchal narratives surrounding sex could act as risk factors for sexual abuse. Narratives that marginalize the experiences and pleasure of girls and women can contribute to the silencing of their voices in sexual encounters, and mainstream pornographic scripts often reinforce such narratives. Moreover, these scripts may normalize the sexualization of violence. Natalie, a pediatric mental health clinician, highlighted the pattern of desensitization that can occur with pornography consumption: “The earlier someone has been exposed to porn, I’ve noticed, the more likely they are to be viewing violent porn currently.” She went on, pointing to the ways that such consumption can have an impact in the development of sexual scripts: “It’s not even just like a cognitive decision of, like, ‘That’s how we now treat women,’ or, like, ‘That’s how we should be treated as women’… it is, now, ‘That is how we derive pleasure.’” Such scripts may then be applied in real-life encounters with a partner: “So, a guy maybe can’t even perform if it’s not somehow aggressive and violent …. We’re talking, like, truly choking, hitting someone with something, punching, um, holding down, like, that sort of behavior.”

Carly, a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE), observed similar patterns of escalating violence and, in her words, “entitlement, I think, especially among teenage boys that I see”. Reflecting on a teen client’s experience of being forced to perform oral sex by a peer who said, “Suck on this, motherfucker,” she asked, “Where do you learn that at 15 years old, you know?” Carly emphasized that while she was unaware of the assailant’s personal pornography consumption, the increase in violent and callous behaviors she had observed among her clients reflects a broader pattern of violence depicted in sexually explicit media. She said, simply, “I think [pornography is] influencing sexual violence and sexual behaviors in so, so many ways.”

3.4. Connections Between Pornography and Abuse

In our conversations with frontline professionals, they frequently made distinctions regarding how modern digital pornography was used or implicated in their cases, often based on the age and/or intention of the perpetrator/initiator of the abuse/problematic behavior. Below, we present these potential mediators between pornography and child sexual abuse.

3.5. Pornography to Child Sexual Abuse Mediators

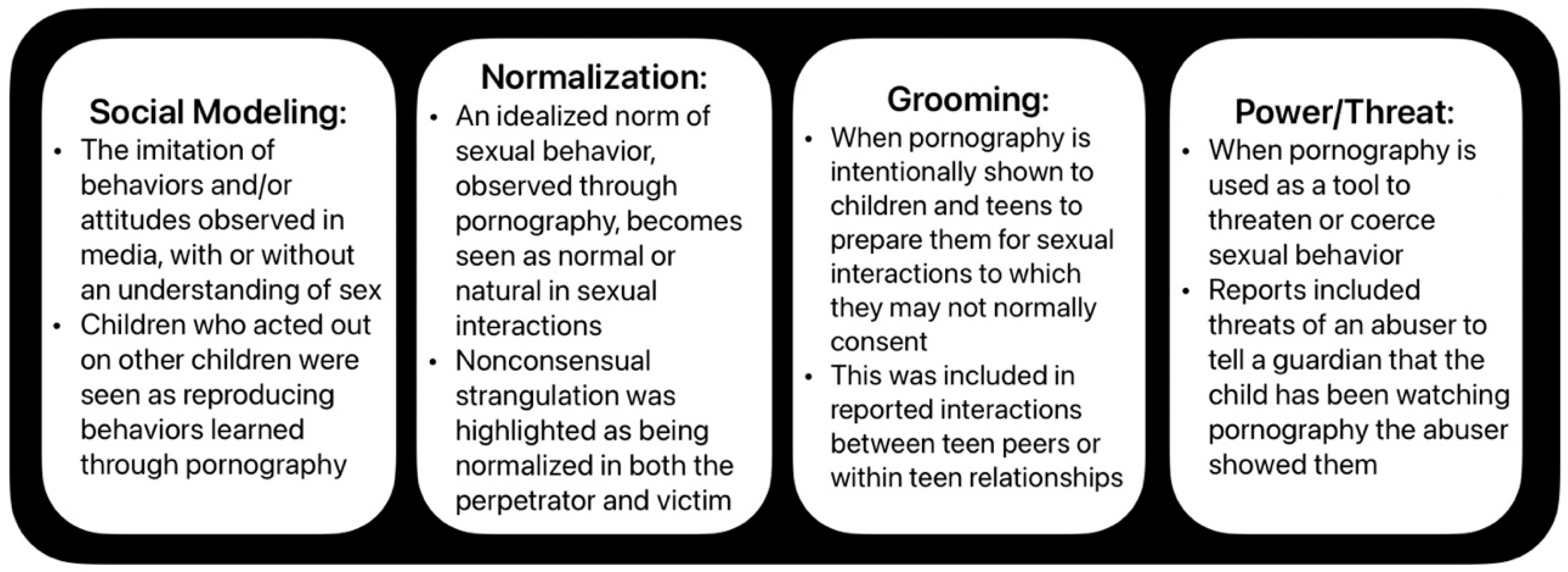

Participants identified several mediators that link pornography to abuse, including social modeling; normalization; grooming; and power/threat (see

Figure 3). These mediators can serve as pathways to abuse following exposure to pornographic material, and they are not mutually exclusive.

Social modeling involves the imitation of behaviors observed in pornography, regardless of the imitator’s understanding of sex or intent to abuse or exert power over others.

Normalization occurs when certain sexual behaviors depicted in pornographic scripts become accepted and even idealized.

Grooming, often seen as the most traditional link between pornography and CSA, involves exposing a victim to pornography to prepare them for abuse, manipulate sexual behaviors, and discourage disclosure. Lastly,

power/

threat describes how some abusers leverage pornography as a tool to coerce additional sexual acts from their victims.

3.5.1. Social Modeling

Sexually explicit media can significantly influence learning and imitation, especially for children who are exposed at an early age. Within this context, children who act out sexually were often referred to as “initiators” by the professionals working with them. These initiators may engage in sexual acts with other children, sometimes without a full understanding of their actions or the concept of sex. Typically, their intent to abuse was perceived as low; however, this does not eliminate the possibility of coercion, nor does it negate the fact that another child may be victimized.

Nicole, a Pediatric Nurse Practitioner, highlighted the evolving perspective on this issue:

So, it used to be that when children exhibited sexualized behavior, we thought, “Well, the only way they would ever know how to do that behavior is because they, themselves, have been sexually abused.” But now, with the rise [of] children being able to access pornography […] we can’t necessarily say, “Oh, they’ve been sexually abused.” They may have had pornography exposure and … now may think this is a way to relate with other children, and/or act out these things.

Julia, a Forensic Evaluation Clinician, shared a concerning example in which a child “stumbled across some sort of cartoon pornography on YouTube and then started, just, like, doing it.” Julia went on, “And then she said she liked how it felt, so she just kept going with it and then got her siblings involved. And then it kind of went from there.” Over time, she pointed out, this “was just normal.”

Ava, a pediatrician who works with survivors of CSA, discussed the direct impact of pornography on children’s sexual development: “I think it has kids engaging in sexual activities at a younger age than they might otherwise be doing it, right?” She noted that although sexual exploration and curiosity is normal and often healthy, pornography exposure “messes that up … by showing [kids] behaviors or things they wouldn’t normally do, right?” Ava further emphasized that the issue extends beyond mere exposure to inappropriate sexual acts; it encompasses the contexts in which these acts are portrayed: “So that’s the other thing that you see in porn, is there’s no consent. …There’s more kind of a domination of one over the other.” She noted that this was often confusing for children because it was both out of context and not developmentally appropriate. For Ava, this spoke a shift in the backdrop of the abuse she saw in her practice. She noted that you would note expect a “a 6- or 7- or an 8-year-old” to be engaging in sexually inappropriate or abusive behavior unless it had been done to them. She reflected, “… it used to be that it happened to them. And now it’s pretty much they saw it on the computer.”

A common observation among participants was that initiating children often lacked abusive intent. Corey, a therapist, explained: “It typically is more of a curiosity … they’re trying to process [what they’ve seen].” However, not all preadolescent children lack understanding or intent when mimicking what they see in pornography. Audrey, a Specialist Safeguarding Nurse, reflected on a case involving an 11-year-old boy who had abused his 3-year-old brother, mimicking sexual behavior he had seen in pornography shared with him from friends at school: “[The social worker assigned to the case] said, ‘Well, if you wanted to know what it felt like, why didn’t you ask one of the girls at school?’ And he said, ‘Because I knew they’d say no.’” Audrey asked:

Is this just a little boy who’s quite clear on the power and control dynamics between him and his little brother? He wanted something, so he exercised that dynamic to get what he wanted? Or are you looking at somebody who, age 11, has already got a sexual interest in 3-year-olds?

Participants’ experiences highlight that the sexual acting out of children does not occur in isolation; exposure to and consumption of pornography frequently serves as the pathway through which knowledge about pornographic and abusive behaviors is acquired.

3.5.2. Normalization

Normalization of sexual behaviors transcends mere imitation by encompassing societal and cultural beliefs about sexuality. Ava, a pediatrician, noted, “…most kids are exposed [to pornography] by eight. So, it’s definitely impacting their sexual script, right? What they think is normal sexual behavior, right?” In participants’ view, this normalization could encompass a range of sexual practices influenced by pornography, with a particular emphasis on physically harmful or dangerous acts.

SANE Carly recounted a case: “I took care of a girl … who was strangled by a same-age boy. And, I was like, ‘I just think that sounds really scary,’ […] and she said, ‘I think he was just trying to be sexy.’” In the interview, Carly asked, incredulously, “Who set the sexual context that being strangled is sexy?” Pamela, a Forensic Interviewer and Director of Forensic Services at a CAC, saw a similar increase in “the male choking a female, and him thinking that’s acceptable.” She went on, “and I would attribute it to some of the pornography.”

The normalization of the pornographic sexual script extends beyond specific acts to include broader beliefs and attitudes regarding social interactions and more complex sexual situations. For instance, Brenda, an Adolescent Treatment Therapist, shared an incident involving a young male client who set up a camera in his stepsister’s room, knowing that she would find it. Having consumed pornography that depicted a stepsibling discovering being watched and that leading to a sexual experience:

And so, his thoughts about the situation was that his stepsister was going to find the camera, and it was going to play out like it did in a pornography video: “She’ll find the camera, she’ll be upset and she’ll come to confront me, and then in the course of that, we’ll end up having sex.”

In this case, the client not only normalized the belief that stepsiblings are valid sexual partners but also viewed the act of being exposed as a voyeur as a legitimate means to initiate and escalate a sexual encounter.

In these instances, both victims and perpetrators/initiators often regarded sexual acts and situations as “normal,” with minors displaying distorted yet advanced understandings of sexual behaviors that align with the pornographic script. Participants observed similar dynamics in instances of teen dating violence. Denise, a Forensic Nurse Examiner, remarked that pornography contributes to “a lot of issues that arise around consent, healthy relationship conversation, ability to navigate your sexual desires and comfort levels.” Catherine, a Forensic Interviewer and CAC Coordinator, added, “I think [‘pornography culture’] very much shows violence towards women.” She went on, “I have had female children come in and say, ‘We were having consensual sex, but he was upset because I wasn’t, I didn’t seem to be like what he saw on porn.’” Many participants noted that the lack of alternative, healthy, accessible sexual scripts intensified the damaging effects of pornography through the process of normalization. Natalie, a Family Advocate, expressed her frustration: “I wonder, sometimes, if […] campus rape would be less of an issue if boys had been able to explore healthy sexuality and connection with support as teenagers and not receive their education from pornography for years!” Amanda, a Child Protection Doctor, echoed this sentiment, criticizing the absence of modeling and education surrounding healthy sexual interactions for young people: “It’s not the sex, it’s the lack of consent.”

3.5.3. Grooming

Many participants observed that adult perpetrators utilize pornography as a tool for grooming or normalizing abuse. Katherine, a District Attorney, noted that many clients have told her that their perpetrators “… made them watch porn and … forced them to act out those movies or the scenes with the offender.” She said the children drew the links between the pornography and the abuse directly: “[The kids are] saying, ‘[…] we watched this movie. And he made me do this to him.’ Or, ‘He made me say the things that the people in the movie […] were saying.’” Tina, a CAC Director, described similar cases involving children as young as four, noting, “it was a grooming process and utilizing porn to get [the victim] doing things that she would see.”

Participants described a shift in how pornography had been implicated in the CSA cases in their practice over the years. In the past, they often encountered cases involving the documentation of abuse through the creation and distribution of CSAM. Diana, a Forensic Interviewer, remarked: “2012 through 2014, it was kids who were being exploited. So, someone was taking pictures or videos of them and putting that out there.” More recently, however, pornography was involved before and in the service of the abuse. Again, Diana: [N]ow, where pornography comes in, […] the perpetrator’s showing [the child] pornographic materials or watching pornography in their presence.” An additional shift in observed patterns, participants indicated that adults were not always the perpetrators. Increasingly, they encountered cases where adolescents used pornography as a tool to coerce sexual interactions with younger children. Gloria, a CAC employee, shared: “[W]e’ve seen younger kids who have been sexually touched by older kids or teenagers … [who have] shown them pornography and literally said, ‘Hey, come here, watch this.’” She went on, offering insight into the initiating child’s possible intentions: “[It’s] not so much in the context of, ‘This is what I want you to do,’ but sort of more in the context of, ‘Haha, isn’t this funny …’, [to] sort of desensitize and normalize it, and breaking down inhibitions and barriers.” Regardless of motivating intent, these types of interactions can have traumatic consequences.

3.5.4. Power/Threat

Participants observed that perpetrators also used pornography as a means of control, threatening to disclose a child’s pornography consumption or to nonconsensually share self-produced images or videos (commonly referred to as “nudes”) to further manipulate or coerce their victims. Forensic Nurse Examiner Denise noted seeing teen relationships that involved “elements of intimate partner violence” including “coercive control: Maybe physical violence, but usually more issues of [pause] bullying, more issues of stalking, more issues of threatening to post something [sexual] on social media.” Sextortion, in other words, was increasingly woven into the patterns of control in these relationships.

In cases involving the production of CSAM, perpetrators sometimes used the documentation of abuse and the threat of disclosure as a further expression of coercive control. For instance, CAC Director Bonnie recounted a case involving a girl who was trafficked, raped, and filmed by her trafficker. The trafficker told her the film was a “training video” designed to teach her how to have sex “the right way.” After being exited and receiving support, the client realized that the video could be shown to anyone. Bonnie noted, “… [the client] goes, ‘Oh, my gosh, that wasn’t a training video, was it? … That was not my training video, oh my gosh, where is it at, oh my goodness,’ and she just started escalating.” And District Attorney Susan highlighted that this dynamic was particularly impactful in adult-to-teen exploitative relationships, stating: “… the adult-to-teen, there is a lot of threatening things that happen. So, it’s, ‘If you don’t send this [explicit photo] to me, I’m going to tell your parents.’” Participants saw this form of blackmail frequently involving coerced, self-produced images (“nudes”), which leads us to the next part of the model.

3.6. Child Sexual Abuse to Pornography Mediators

Participants noted that while pornography exposure often precedes or leads to abuse, it can also occur before or simultaneously with such exposure. In these cases, pornography is implicated through the documentation of the abuse and the dissemination of sexually explicit materials, which includes both CSAM and instances of “revenge porn.” Additionally, some clients turned to pornography as a coping strategy or a means of processing their abuse.

Historically, every instance of “child pornography” involving real children represented a documentation of CSA. In this sense, (child) pornography has always been directly connected to CSA, as it reflects an act of CSA that can be exploited and extended through the distribution and consumption of images and videos. Although participants recognized this in their work, they frequently mentioned “revenge porn” as the most common form of post-abuse implication, where self-produced sexual images were used to blackmail a victim or extort sexual behaviors to which the victim would not normally consent. The increased prevalence of self- or other-produced explicit images presented both a significant challenge and a notable shift in their caseloads. Angela, a Pediatric SANE, remarked: “I would say another big trend we’re seeing is, like, [nonconsensual sharing of] nudes and videos, too. […] It is a form of extortion abuse, because these are out there forever. [T]hat’s a huge thing that we’re seeing.” Cynthia, a CAC Director, added, “[sexting] definitely comes up a lot in teen stuff. It’s, ‘They took a picture of me and then … they wouldn’t give it back’ …. Or, … ‘They said if I didn’t have sex with them … they would send [the photos] out.’” Diana, a Forensic Interviewer, reported witnessing the shift toward “revenge porn” in cases of child-on-child abuse: “[We see] kids just being left to their devices and, you know, maybe even sending a nude to a same-age child, not realizing that it’s technically child porn. I mean, and then it’s becoming a bigger issue where it’s being passed around.”

Participants frequently discussed what would have been considered “normal” or “healthy” stages of sexual exploration and development among children that have been complicated by digital technology and social media. Nicholas, a forensic interviewer, observed, “… it was probably a normal sort of behavior. But with the technology, they’re able to take pictures.” Thus, rather than being a developmentally appropriate experience shared between peers, there is now a digital artifact that depicts sexually explicit imagery of a minor. Ava, a pediatrician, remarked: “… the kind of typical exploratory behaviors are not really allowed to develop naturally…. [Now there are] lots of photos, lots of videos, those never go away, you know?” Like Diana, Ava noted that children might not be aware of the power dynamics at play: “[W]e’ll see, like, there’s a girl and a boyfriend. And boyfriend sends her nude picture to his friend, and that friend sends it to all their other friends…. That certainly happens. But kind of, I mean, it is child pornography, but of a different intention.” Underscoring the reality of educational, clinical, and legal settings as negotiated zones of violence, the discovery of such images could have legal ramifications for the children involved. As Nicholas put it: “[Kids] don’t realize that they’re producing child pornography and can be charged with that.” Participants emphasized that criminalizing and labeling children, who are arguably more accurately seen as victims, is not conducive to support, healing, or positive intervention.

Participants also noted that pornography sometimes plays a role both in the abuse a child experiences and as an outlet in the aftermath of the abuse. Katelyn, a District Attorney, shared, “[One victim] did admit when she first came to counseling that she was addicted to porn because she was exposed during the trauma.” In other cases, participants pointed out that some survivors of abuse not involving pornography sought out pornography as a coping mechanism in the aftermath of the abuse. Amanda, a Child Protection Doctor, explained that children searching for understanding about their trauma are likely to encounter pornography online, even if it is not their intention: “[I]f you’re a younger child and you’ve had this [trauma], and […] you’re just trying to understand what has happened to you, and you’re looking for stuff online, of course pornography comes up, you know?” Brenda, an Adolescent Treatment Therapist, agreed: “Some of my clients who are victims discovered pornography after their abuse happened and that became a sexual outlet for them.” As demonstrated by Katelyn’s client, these attempts to process or cope can introduce their own challenges, including issues of “addiction” and habituation.

A final manifestation of pornography’s implication in ongoing and post-abuse dynamics involves sexual reactivity—sexual behavior exhibited by children who have survived abuse, been exposed to sexual content, or grown up in sexually charged environments. This can include not only the consumption of pornography but also the self-production of sexual images. In Brenda’s earlier example, she elaborated that some of her clients began “… exchanging and … creating pornography” in their efforts to cope with the trauma they had experienced, often compounding their trauma. Participants emphasized that these patterns reflect complex dynamics where pornography serves as both a dynamic consequence and a facilitator of ongoing harm and violence, necessitating critical understanding and intervention.

3.7. Interrupters

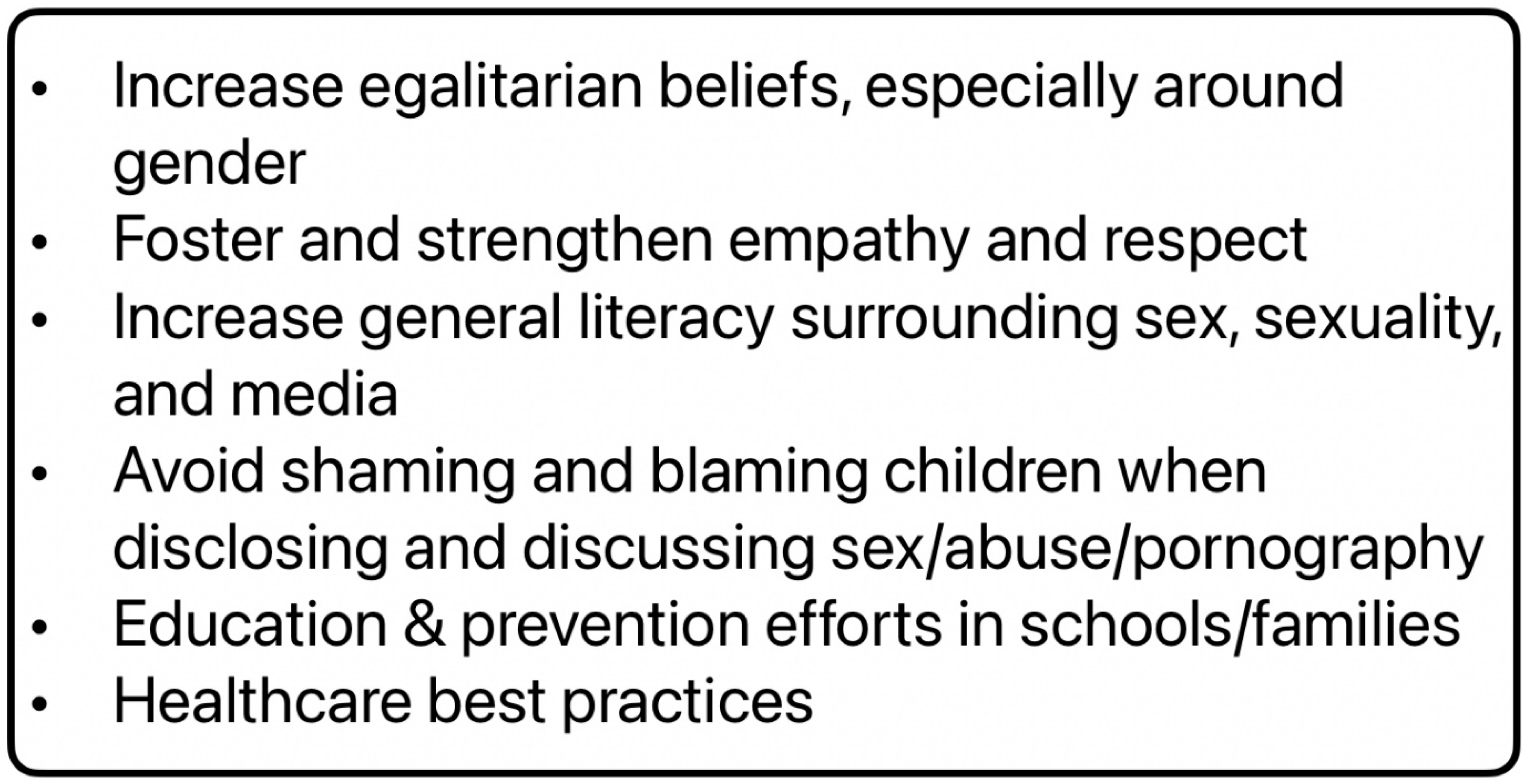

Conversations with front-line professionals illuminated a variety of potential solutions for addressing CSA (

Figure 4). Through the coding process, the research identified the following as emergent across interviews: promoting egalitarian beliefs, particularly regarding gender; fostering empathy and respect; enhancing literacy surrounding sex, sexuality, and media; avoiding shame and blame when children disclose or discuss topics like sex, abuse, or pornography; strengthening education and prevention efforts in schools and families; and, following healthcare best practices. While many of these suggestions were actionable in terms of policy and protocol, others emphasized broader cultural changes necessary for reducing CSA. These proposed “interrupters” can be understood through the lens of feminist and sexual script theories, grounded in gendered power relations and set against culturally available and dominant narratives about sex and sexuality and young people’s understandings of intimacy, consent, and abuse.

Amanda, a Child Protection Doctor, elaborated on how a cultural shift could benefit not only those who have experienced sexual abuse, but the broader community. She noted that supporting egalitarian beliefs would not prevent all child abuse from happening, “but it just gets into more people that idea of going to an, ‘Oh, I know, this is what love is. This is what a healthy relationship is. This is what respect and mutual enjoyment and not power-over, but power-with, looks like.’” Natalie, a pediatric mental health clinician, echoed this sentiment, asserting, “…it’s not sex that’s the problem; it is the mental picture and the relation and the huge lack of understanding of the humanity of two people.” Through the lens of feminist and critical sexual scripts theory, participants were calling for a shift away from patriarchal frames of sex tied to dominance, entitlement, and the objectification of girls and women, and toward a more relational model grounded in mutuality, communication, and consent. Such a shift could “interrupt,” as the participants noted, the connections between pornography and all forms of sexual abuse while supporting healthier interpersonal relationships. Pornography, in this view, can be understood not just as a form of individual consumer practice but as a site through which patriarchal norms and hegemonic masculinity are displayed, rehearsed, and legitimated.

Many respondents stressed the need for comprehensive education for guardians, healthcare workers, and caregivers, advocating for approaches that extend beyond mere technological literacy to encompass a deeper understanding of sex and pornography. They emphasized the importance of avoiding shame and blame when children disclose abuse or exposure to pornography. Billy, an Associate Director of a CAC, remarked: “It’s been a harmful, potentially damaging scenario for [the] child…. And, certainly, having mom and dad yell at them and punish them is not going to incline them towards talking with their parents about it.” This underscores the necessity of creating an environment where children feel safe discussing sensitive topics without fear of reprimand. Jane, a therapist, further emphasized, “We aren’t talking about it enough and people don’t know how to talk about it.” Angela, a Pediatric SANE, reinforced the importance of maintaining regular conversations with children about these issues, stating, “Just having conversations with our kids regularly about these things and checking in with them is really important.” In this context, our participants’ calls to interrupt or diminish the connection between pornography and CSA are part of a broader initiative to normalize open, appropriate, and inclusive discussions about sex, sexuality, and relationships between children and trusted adults that can function as compelling and realistic counter-narratives to the hegemonic, patriarchal, and pornography-informed scripts that view sex as conquest and control. Counter scripts can function as resources on which young people can rely to interpret and resist abusive and coercive situations.

Finally, several participants lamented a lack of understanding and awareness among some colleagues. They advocated for routine screening for pornography exposure within healthcare disciplines. They noted that doing so often brings to light issues that might otherwise go unexamined. Angela, a pediatric SANE, explained: “… we also screen for exploitation and trafficking. And, in that we talk about ‘nudes’ and other things and that’s, that social media piece gets picked up very quickly there.” Given the normalization of pornography in young people’s lives and the ways that exposure and consumption may shape their sexual scripts, omitting screening questions about pornography could leave critical connections between pornography and abuse unexamined. As participants emphasized, practitioners and anyone supporting young people must disrupt these patterns of normalization to bring these issues to the forefront.

Participants’ calls to identify and implement such best practices reflect an effort to disrupt the normative role of pornography in young people’s lives. Rather than a private choice or taken-for-granted aspect of the culture, pornography exposure and consumption in the lives of young people is better understood, they assert, as a personally, interpersonally, and socially consequential practice that must be rendered visible and problematized within institutional encounters in the system of care. In bringing the range of “interrupters” into sharper focus, the front-line professionals in this study situate everyday points of interaction and engagement between adults and children acting within situated and negotiated “zones of violence/care” within larger structures of gender inequality, digital media economies, and cultural norms.

3.8. Focus Group Review: Participant Responses to the Model

After completing the model, we organized eight focus group discussions with available participants to review the findings, gather feedback, and make any necessary revisions. Across these groups, participants emphasized the value of this process and the importance of research to inform their work. They described the interviews, the emergent model, and the focus group discussions as “important” and “so valuable.”

More specifically, participants found the model to be sensible, accessible, and useful, offering a potentially valuable resource for providers across multidisciplinary support teams and the broader public, particularly in “combating shame.” This highlights the dialectical relationship between the home and clinical/forensic settings as both potential zones of violence and zones of healing and accountability. CAC Director Elise explained: “[Using the model] is a way to help our families conceptualize this interaction [between pornography and CSA] and what’s going on, and to help target as we’re talking through [possible interventions].” Nicholas, a Forensic Interviewer, highlighted the model’s potential in educating staff, interns, and volunteers within the multidisciplinary team that supports children: “… that involves child protective services, the school system, forensic nurses, law enforcement, and sometimes some federal agencies…. I think [this model] would be a huge benefit in those meetings.” Furthermore, Forensic Interviewer and CAC Director Catherine indicated the model’s potential utility in court cases, highlighting that, “depending on the case, [the model could] be used to help educate the jury. Because, again, unfortunately, there’s a lot of myths surrounding child sexual abuse, pornography, the use of pornography, and access to pornography, y’know, when it comes to these types of cases.”

Beyond the need for resources to support training and education, many participants specifically highlighted the necessity for established best practices within the field and the research needed to support those efforts. Carly stated, “… one of the biggest needs that I’ve heard from other professionals in this space is: We need best practices, and they just don’t exist.” CAC Director Elizabeth concurred, noting, “Well, we need y’all [academics] to be the conduit, because those of us who are doing the work don’t have time to do your research, even if we want to!” Lori, a therapist and Family Advocate at a CAC, succinctly stated, “… not only, like, the training and getting awareness out there, but, like, people actually changing the way they’re doing things or adding, implementing these things that they’re learning. That’s what’s going to make the real change.”

Overall, the focus groups highlighted the model’s potential usefulness as a resource for frontline providers and as a catalyst for systemic change and ongoing research. The consensus was clear: addressing the complex issues of pornography and CSA requires collaborative efforts informed by research, grounded in best practices, and committed to cultural transformation.

4. Discussion

The patterns evident across our participants’ accounts illustrate how digital environments can function as zones of violence—sites in and through which harm is enabled, normalized, archived, and replicated across time and physical space. In the contemporary era, children’s bedrooms, smartphones, tablets, computers, gaming systems, and social media accounts are not neutral backdrops to abuse but mediated “geographies of mundane violence” (

Bork-Hüffer et al. 2023, p. 170). These are spatially organized environments that can facilitate access, grooming, surveillance, coercion, and the persistence and documentation of harm through digital traces—the “records of activity (trace data) undertaken through an online information system” (

Howison et al. 2011, p. 769)—in ways that are woven into the fabric of everyday life. Further, our findings demonstrate how systems of clinical and legal care and response—including Child Advocacy Centers, law enforcement offices, child protection services, victim advocacy agencies, legal offices, and medical and mental health settings—serve as institutional sites that mediate harm, care, credibility, and accountability. These are not mere service locations; they are physical spaces and environments in which trauma is translated into evidence, where children’s narratives are validated, constrained, or rendered invisible, and where institutional power shapes the terms and meanings of recognition, intervention, recovery, and justice.

The model developed in this paper identifies risk factors that can increase children’s exposure to pornography and their vulnerability to abusive and problematic sexual encounters. Importantly, it also highlights the feasibility of interventions to disrupt these dynamics across the digital, physical, and material geographies that shape children’s lived realities. Proposed strategies include implementing screening questions regarding pornography exposure and consumption within clinical and forensic spaces, providing material support for families and guardians, and advocating for comprehensive, inclusive, and digitally literate sex and sexuality education for both young people and their caregivers.

These measures align with over three decades of research demonstrating the positive impact of evidence-based, broadly defined, inclusive, and affirming comprehensive sex education throughout children’s educational experiences (see

Mark et al. 2021;

Stepahanie 2024;

Suwarni et al. 2024). Such education has been shown to enhance young people’s appreciation of sexual diversity, reduce dating and intimate partner violence, foster healthy relationship skills, prevent CSA, improve social and emotional learning, and increase media literacy (

Goldfarb and Lieberman 2021).

Systemic reforms in education and policy, guided by ongoing research and best practices, represent critical pathways for prevention, intervention, and the establishment of safer environments for children. These initiatives not only address immediate risks but also promote a cultural shift toward healthier perceptions and discussions of sex and sexuality, which are essential for long-term societal change.

4.1. Limitations

A qualitative research project based on interviews and focus group discussions with 50 frontline professionals supporting survivors of CSA cannot be generalized to the entire population of such professionals. Likewise, the patterns identified by these providers cannot be applied to all survivors of CSA. Therefore, the primary aim of this project was analytic rather than substantive generalizability (see

Yin 2009). The insights shared by these providers illuminate their perceptions of potential pathways through which pornography may be implicated in both the perpetration of and response to CSA. Notably, as these providers reflected on the changes they have observed throughout their careers, pornography frequently emerged as a central theme in their narratives.

4.2. Future Research Directions

Future studies could evaluate providers’ assessments of the model presented here. If CACs adopt screening questions regarding pornography exposure and consumption as a best practice, researchers could track changes in how these materials are implicated in clients’ experiences and treatment trajectories. Furthermore, if communities implement programming in schools, for parents, and/or within the broader community that emphasizes digital and media literacy and fosters inclusive cultures of consent, researchers could assess the impact of these initiatives on the experiences and identification of CSA and treatment/support within those communities. Additionally, conducting interviews and/or surveys with survivors of CSA could provide deeper insights into their experiences with pornography in relation to the abuse they endured.

4.3. Prevention, Clinical, and Policy Implications

The accounts from frontline professionals presented here emphasize that pornography is a normative element of many young people’s gender and sexual development, often intertwined with their experiences of abuse. These patterns reveal consistent connections to social learning and sexual scripts theories (

Bandura and Walters 1977;

Wright 2011). Early exposure to pornography, especially in the absence of healthy alternatives within familial, educational, or cultural contexts, can distort young people’s sexual scripts, potentially normalizing abusive and problematic behaviors. This normalization may heighten vulnerability to exploitation and abuse, possibly explaining the observed increases in child-on-child abuse and sexual acting out. Pornography can serve as a mechanism for normalizing harmful behaviors, a grooming tool for perpetrators, a means of social control and shame, and an often maladaptive coping strategy for survivors. These insights highlight the urgent need for systemic reforms in education, policy, and clinical practice aimed at mitigating these risks and addressing the pervasive influence of pornography on youth development and safety. More specifically, this research supports calls for:

Enhanced Education and Training: Increase education and training focused on pornography and CSA for professionals working with children.

Best Practices Identification: Establish best practices, including the routine use of age-appropriate screening questions by professionals addressing pornography exposure, consumption, and self- or other-produced explicit images and videos.

Policy Reforms: Implement policy reforms to address the legal classification and prosecution of minors as “sex offenders” when they should be recognized as victims in need of support and intervention.

Public Awareness Campaigns: Launch campaigns aimed at educating parents, guardians, and the broader community about the potential risks associated with pornography exposure and its connections to CSA.

Comprehensive Sex Education: Support comprehensive, empirically grounded, affirming, and inclusive sex and sexuality education that fosters discussions of sexual respect and critical media literacy.

Support for Childcare and Community Networks: Increase funding for high-quality childcare, parental/guardian support networks, and broader initiatives to address systemic risk factors and reduce inequality.

Research Funding: Allocate more funding for research to further investigate these issues, particularly through longitudinal studies that can inform evidence-based policy decisions.

Multi-Agency Collaboration: Enhance collaboration among child protection agencies, law enforcement, educators, and health and mental healthcare providers to create a coordinated approach for CSA prevention and response.

Regulations for Online Platforms: Enforce stricter regulations and hold online platforms accountable for hosting or disseminating CSAM and those having lax restrictions on minors’ access to harmful content.

Content Moderation Support: Advocate for more robust content moderation across social media and video-sharing platforms to protect minors from harmful material.

5. Conclusions

All participants in this study provided support to survivors of CSA and their families. Despite their diverse professional roles, gender identities, nationalities, regional settings, racial identities, religious beliefs, and personal views on pornography, all 50 respondents recognized a clear interconnection between pornography and CSA. They noted that both factors contribute to the evolving patterns of abuse they have observed across their careers, centering pornography and CSA as mediated geographies of violence entangled across online and offline spaces.

Most participants emphasized the benefits of raising awareness about the links between pornography and CSA, both among practitioners and the broader public. They stressed the importance of addressing systemic (distal) and individual (proximal) risks that contribute to both CSA and exposure to pornography. Participants called for policy changes that support fundamental social needs—such as affordable housing, accessible childcare, comprehensive healthcare, fair wages, and inclusive sex and sexuality education—as vital steps in reducing systemic vulnerabilities. These structural reforms aim to create an environment that is less conducive to exploitation and abuse.

In addition to systemic reforms, participants highlighted the importance of interpersonal and community-based solutions. These include believing children when they disclose abuse, providing unwavering support, avoiding shaming or blaming victims, and implementing stricter monitoring of children’s technology use. Together, these measures seek to cultivate a culture of trauma-informed, child-centered, compassionate, and critically engaged care.

The model developed through this project is intended as a valuable resource for frontline workers and all individuals involved in supporting children. It aims to guide their efforts in delivering evidence-based, culturally sensitive, and ethically grounded care and advocacy. Ultimately, this integrated approach aspires to reduce the prevalence of CSA, to promote healthier sexual development, and to foster safer environments for children worldwide.