1. Introduction

According to

Walters (

2020), criminogenic thinking is especially conducive to unlawful behavior. This encompasses errors in reasoning, an inability to realize the effects of one’s actions, decision-making based primarily on emotions rather than on reason, and an unrealistic self-image. Criminogenic cognition is also a complex system from which justifications and rationalizations of antisocial behavior are drawn and which entails a weak capacity for distinguishing between one’s needs and wishes (

Walters 2020).

Rivera and Veysey (

2018) similarly describe criminogenic cognition as a reduced capacity for decision-making in situations involving danger.

Other researchers who have conducted in-depth studies of the phenomenon of criminogenic cognition include

Tangney et al. (

2007), who suggest that criminogenic cognition consists of a set of cognitive distortions that serve to rationalize and perpetuate criminal behavior. With the aim of quantifying such cognitive distortions,

Tangney et al. (

2012) developed the Criminogenic Cognitions Scale (CCS) based on research through which the relationship between morality and criminal recidivism was examined. Drawing on concepts from restorative justice theory, this instrument is composed of 25 items that pertain to five dimensions: (1) Notions of Entitlement (e.g., “When I want something, I expect people to deliver”); (2) Failure to Accept Responsibility (e.g., “Bad childhood experiences are partly to blame for my current situation”); (3) Short-Term Orientation (e.g., “The future is unpredictable and there is no point planning for it”); (4) Insensitivity to the Impact of Crime (e.g., “A theft is all right as long as the victim is not physically injured”); and (5) Negative Attitudes Toward Authority (e.g., “Most police officers/guards abuse their power”).

In their study aimed at testing the reliability, validity and predictive utility of the CCS,

Tangney et al. (

2012) analyzed the correlations between CCS scores and those obtained using other psychometric tools. These tools included the Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI;

Morey 1991), particularly the Aggression Scale (AGG), the Antisocial Personality Scale (ANT) and the Violence Potential Index (VPI), employed for the analysis of personality traits. To assess shame-proneness, guilt-proneness and externalization of blame, the cited authors applied the Test of Self-Conscious Affect—Socially Deviant Version (TOSCA-SD;

Hanson and Tangney 1996), whereas for assessing empathy, they applied the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI;

Davis 1980). They also used the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2;

Straus et al. 1996), the Brief Self-Control Scale (BSC;

Tangney et al. 2004), the Inclusion of the Community in Self Scale (ICS;

Mashek et al. 2007), and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE;

Rosenberg 1965).

Tangney et al. (

2012) argue that criminogenic thinking is a “dynamic factor that is amenable to cognitive-behavioral interventions” (p. 1355). The results of their study show that the CCS is a reliable psychometric instrument that can be used to identify high-risk inmates as well as to adapt interventions to the specific criminogenic needs of each individual offender.

The psychometric value of the CCS has been further validated in a study conducted by

Jamil and Fatima (

2018). They standardized and translated the instrument into Urdu and applied it to a sample of 452 adolescents. Moreover,

Sadeghi Shahrakht and Ahi (

2019), in their study on 397 students at the Birjand University of Medical Sciences, investigated the factor structure, validity and reliability of the CCS, and also obtained results that support the scale’s utility for the analysis of criminal behavior.

As the overview of the literature presented above shows, prior studies attest to the efficacy of the CCS, both in terms of its validity and in terms of its methodological reliability.

Research in the field of criminology has analyzed the specificities of criminal thinking in the Romanian context. Regardless of whether these studies focused on criminal profiling (

Țical 2018;

Jitariuc and Cojocaru 2023) or on the structures of organized crime, namely how criminal thinking is adapted to the socio-economic and political context in Romania (

Neag 2020;

Ilie 2024), all of them contribute to the development of more effective crime prevention strategies.

Some researchers have also analyzed how cultural and traditional factors influence the thinking and behavior of criminals in Romania (

Neag 2022). These studies have highlighted the role of socio-economic conditions, such as poverty, lack of education, and job opportunities, which can influence the decision to commit crimes. In Romania, certain communities may be more vulnerable to crime due to these circumstances.

Consequently, we sought to validate this instrument in a Romanian-language version, recognizing its importance in the context of Romania, where a reduction in criminal recidivism is a state objective. Taking into account that over the past 10 years, Romania ranks among the top five EU countries for crimes such as intentional homicide and human trafficking (

Eurostat n.d.), such an instrument could contribute to recidivism prevention efforts and help with managing and prioritizing specialized assistance offered to inmates.

At the same time, the need to validate this instrument on the population of incarcerated individuals in Romania has also arisen from the importance of building a professional framework based on empirically validated procedures and interventions. This aspect provides particularly useful support to specialists in the field of justice, especially those engaged in evaluating criminal behavior or developing measures to prevent delinquency. In this regard, the limited number of psychological tools adapted to the population of offenders in Romania that can be used in practice is highlighted by the complexity of the evaluation and intervention process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objectives and Hypotheses

The general objective of this study is to highlight the complexity and importance of criminogenic cognition within the current context of the penitentiary environment in Romania.

The specific objectives were to test the psychometric characteristics of the Criminogenic Cognition Scale on a sample of incarcerated individuals in Romania and to outline the variability of criminogenic cognitions based on socio-demographic variables and psychological factors.

Following these specific objectives, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H1. It is assumed that the Criminogenic Cognition Scale developed in international contexts is valid and relevant for the population involved in criminal behaviors in Romania.

H2. It is possible that certain socio-demographic variables and psychological factors may exert variability on the dimensions of criminogenic cognitions.

2.2. Translation

The CCS was translated and adapted into Romanian following the International Test Commission’s guidelines for translating and adapting tests (

International Test Commission 2018). Thus, the first stage consisted of obtaining permission from the intellectual property rights holder to perform this adaptation. Communication was conducted through e-mail, such that written consent was obtained.

The second stage consisted of translation of the scale into Romanian by two psychologists who are native speakers of the language. Each of them worked independently to produce a translation of each item, having received identical instructions for the task. Additionally, the construct measured by the scale was analyzed from the point of view of its meaningfulness and applicability to the target culture to minimize the potential effect of any cultural and linguistic differences between the source and target cultures that are irrelevant to the intended uses of the instrument.

The third and final stage consisted of an expert psychometrician revising the two completed translations and unifying them into a single version to be applied as a pilot test. The translators presented all the difficulties they had encountered and discussed elements in the scale that they had deemed irrelevant to Romanian culture. The final version of the scale is presented before references (

Appendix A).

2.3. Sample

The CCS was administered in eight Romanian penitentiaries to a total sample of 460 prisoners with ages ranging between 21 and 71 years (mean age = 39.23, SD = 10.36). Approximately 90% of the participants were male. Participants were selected according to the following criteria: (a) Romanian nationality; (b) they had been definitively sentenced; (c) they had given voluntary consent to participate in the study; (d) they were literate; and (e) a minimum total sample of 200 participants.

The subject sample was selected according to the general recommendations of the International Commission regarding the guidelines for the translation and adaptation of tests (

International Test Commission 2018); specifically, there should be a minimum of 200 subjects. With the research universe (23,144—the average number of incarcerated individuals in Romania), the sample of 460 subjects allows for confidence in the study results with a margin of error of ±4.52% at a confidence level set at 95% (Z-score = 1.96), thus adhering to methodological rigor (the margin of error does not exceed the threshold of 5%).

2.4. Procedure

The materials to be administered to the participants were prepared, along with instructions to follow in the event of language or cultural barriers or problems with administration and response methods that could affect the validity of the inferences drawn from the scores obtained. Participants with sufficient literacy skills were asked to fill out questionnaires in paper-and-pencil format, without a time limit.

Participants were also handed an informed consent form, containing an overview of the objectives of the present study; a description of the risks to which they would be subjecting themselves, of the level of discomfort that they could expect, information regarding personal data confidentiality, including a specification of the persons who would have access to participants’ data; and the provision that they would be able to withdraw from the study at any time, without suffering any repercussions. In accordance with the legislation in force and the regulatory framework governing the credit system for inmates, they were credited for their voluntary participation in this study.

To minimize possible biases caused by the ordinal nature of the Likert scale, such as the tendency to choose neutral responses to avoid making a firm commitment, the authors used several strategies. Clear explanations of the scale used were provided, including example situations for each response category. In this way, the authors ensured that the responses provided by the participants were as representative as possible.

2.5. Description of the CCS

At this stage, the objective was to verify the factor structure of the CCS, which is composed of 25 items and was proposed by

Tangney et al. (

2012), on an independent and current sample in Romania. Dimensionality tests were used to determine whether the measurement of items, factors and their functions would yield the same results in two independent samples in different sociocultural times and spaces. For such tests, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) were used.

The CCS has been linked by

Tangney et al. (

2012) to “criminal justice system involvement, self-report measures of aggression, impulsivity, and lack of empathy” (p. 1340). Its function is to assess respondents’ levels of criminal thinking patterns. The responses for each item are given on a 4-point Likert scale, where 1 =

strongly disagree; 2 =

disagree; 3 =

agree; and 4 =

strongly agree.

The CCS was designed to assess 5 dimensions (factors): (1) Notions of Entitlement (NOE), (2) Failure to Accept Responsibility (FAR), (3) Short-Term Orientation (STO), (4) Insensitivity to the Impact of Crime (IIC) and (5) Negative Attitudes Toward Authority (NATA) (

Table 1). The results obtained by

Tangney et al. (

2012) on a sample of 552 inmates (male and female) support the reliability, validity, and predictive utility of the measure.

2.6. Methods for Validating the CCS in Romania

The Romanian sample consisted of 460 inmates from eight prisons, each located in a different county of Romania. For Likert scales, it was necessary to investigate reliability estimates and factor structures based on polychoric correlation matrices, taking into account the ordinal nature of the data. For this purpose, the statistical analysis programs EQS 6.4 (

Bentler 2006), lavaan 0.6–12 (an application package in R for SEM [Structural Equation Modeling]) and Stata 13 (

StataCorp 2013) were used.

Given the research objectives, it was decided that Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) should be used to identify and possibly eliminate items that do not contribute to the measurement of the construct. At the same time, this statistical tool was considered necessary to assess whether the observed variables adequately measure the latent factors. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was used to identify the number and type of factors that influence the observed variables. This allowed for data exploration, as well as for the discovery of possible unforeseen relationships, an essential aspect at this stage of the research.

EFA of the 25 items of the CCS revealed that the data are best represented by a five-factor model. This conclusion was based on a graphical inspection of a scree plot of the eigenvalues (y-axis) as a function of the number of factors in the model (x-axis).

One of the reasons for performing a factor analysis was to reduce the large number of variables describing the complex concept to a few interpretable latent variables (factors). In other words, the goal was to arrive at a smaller number of interpretable factors that would account for the variability of the greatest amount of data. In practice, the elbow of a curve, i.e., where the slope of the curve levels off, indicates the number of factors that should be generated by the analysis. In the present study, an elbow could be observed for five factors.

The Schwarz statistical BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion) was analyzed for each possible factorial model, as an additional general approach to factorial model selection, which favors simpler models over more complex models. A difference between BIC values of between 6 and 10 constitutes strong evidence in favor of the model with a lower BIC. The minimum BIC value (1469.74) was obtained for the five-factor model.

The reliability coefficients were Cronbach’s alpha = 0.849 and Reliability Coefficient Rho = 0.873.

Scores for the five dimensions of the CSS were calculated according to the original methodology as means of the associated items. The total score for the CCS (CCS-TS) was calculated as the average across all 25 items.

3. Results

3.1. Results for Each CSS Dimension

The results obtained on the Romanian sample were consistent with the model proposed by the creators of the instrument (

Tangney et al. 2012) for the five dimensions of the CCS. The validity of the five dimensions in the Romanian sample was verified using a CFA adapted for categorical data.

For the NOE subscale (items 1, 6, 16, 19, and 23), a single-factor CFA in lavaan with the WLSMV estimator indicated acceptable performance, yielding the following values for the main quality indicators: Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.953 and Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.906. The value of the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) (0.111) was >0.08, indicating a poor model–data fit; however, for the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), a similar indicator, a satisfactory value of 0.070 < 0.08 was obtained. Regarding internal consistency, the following reliability coefficients were obtained: Cronbach’s alpha = 0.683, Reliability Coefficient Rho = 0.691, and Maximal Weighted Internal Consistency Reliability = 0.761. The values of the coefficients were acceptable considering that only 5 items were included in the analysis. Based on the above indicators, it can be considered that the set of the five items 1, 6, 16, 19, and 23 was in a significant and consistent relationship with a single latent factor, termed Notions of Entitlement.

For the FAR subscale (items 2, 5, 9, 15, and 22), a single-factor CFA in lavaan indicated a particularly high model fit, as shown by the model quality indicators CFI = 0.996 > 0.950, TLI = 0.993 > 0.950, RMSEA = 0.026 < 0.08 and SRMR = 0.035 < 0.08. The reliability coefficients Cronbach’s alpha = 0.707, Reliability Coefficient Rho = 0.712 and Maximal Weighted Internal Consistency Reliability = 0.753 were particularly good. This supports the conclusion that the FAR subscale was valid for the Romanian sample.

For the STO subscale (items 3, 8, 18, 24 and 25), a single-factor CFA in lavaan yielded CFI = 0.950, TLI = 0.900, RMSEA = 0.081 and SRMR = 0.062. The values for the internal consistency coefficients were Cronbach’s alpha = 0.626, Reliability Coefficient Rho = 0.635, and Maximal Weighted Internal Consistency Reliability = 0.728, which can be considered acceptable as we dealt with only 5 items. Thus, it can be considered that overall, the quality indicators of the factorial model were acceptable and that the STO subscale was valid for the Romanian sample.

For the IIC subscale (items 4, 7, 11, 12, and 14), a single-factor CFA in lavaan indicated acceptable performance: CFI = 0.932 and TLI = 0.864. The values of RMSEA = 0.064 < 0.08 and SRMR = 0.051 < 0.08 were both satisfactory. The internal consistency was more modest, with Cronbach’s alpha = 0.537 and Reliability Coefficient Rho = 0.581. Overall, the quality indicators of the factorial model provided acceptable evidence that the IIC subscale is valid for the Romanian sample.

As for the NATA subscale, it could be cautiously considered valid for the Romanian sample. A single-factor CFA indicated acceptable performance (CFI = 0.941 and TLI = 0.883); however, the RMSEA value of 0.117 > 0.08 was not satisfactory, whereas the SRMR value of 0.076 < 0.08 was just below the cutoff value. Internal consistency was modest, with Cronbach’s alpha = 0.529 (with items 10, 17 and 20 being reverse coded) and Reliability Coefficient Rho = 0.586.

In the present study, an RMSEA value below 0.08 was deemed an acceptable fit index, in alignment with the theoretical underpinnings of the measured construct and supported by prior empirical evidence. As noted by

Hu and Bentler (

1999), a threshold of 0.08 may be considered acceptable under certain conditions, particularly when accounting for the influence of sample size on the precision of RMSEA estimates.

3.2. Total Score for the CCS (CCS-TS)

Descriptive statistical data and correlations between dimension (subscale) scores and the CCS-TS were presented in

Table 2. An analysis of score distribution using the Monte Carlo method with 1000 iterations indicated a normal distribution only for the CCS-TS, at a significance level of

p = 0.328.

All scores correlated significantly, except for the correlation between NOE and NATA. No outliers were identified by inspection of Mahalanobis distances.

3.3. Variability of Criminogenic Cognitions in the Studied Sample

Kruskal–Wallis tests showed significant differences for some CCS dimension scores and the type of offense for which the inmate was incarcerated as follows: FAR (

χ2(8) = 31.650,

p < 0.001), STO (

χ2(8) = 27.760,

p = 0.001), IIC (

χ2(8) = 20.725,

p = 0.008) and CCS-TS (

χ2(8) = 26.344,

p = 0.001). The mean ranks of the scores are presented in

Table 3. The lowest mean ranks were observed for financial offenses, and the highest mean ranks were observed for sexual offenses.

Significant differences were observed for some CCS scores depending on the penitentiary in which the inmate was incarcerated. Kruskal–Wallis tests yielded the following results: FAR (χ2(6) = 28.812, p < 0.001), STO (χ2(6) = 26.516, p < 0.001), and CCS-TS (χ2(6) = 25.893, p < 0.001). The highest mean ranks for the FAR (307.08), STO (317.97), and CCS-TS (312.93) scores were associated with the Vaslui penitentiary. At the other extreme was the Bistrița Penitentiary, where the mean ranks were below 200.00.

Kruskal–Wallis tests also showed significant differences for some CCS scores depending on the level of education (

Table 4) for the FAR (

χ2(4) = 19.359,

p = 0.001), STO (

χ2(4) = 29.467,

p < 0.001), IIC (

χ2(4) = 21.919,

p < 0.001) and CCS-TS (

χ2(4) = 24.599,

p < 0.001) scores. The lowest mean ranks for the FAR, STO, IIC, and CCS-TS scores were associated with a post-high school education.

In terms of inmate civil status (

Table 5), significant differences were observed only for the FAR subscale, with the Kruskal–Wallis test returning the following results: FAR (

χ2(4) = 11.359,

p = 0.023 < 0.05). The highest mean rank for the FAR score (341.25) was associated with widowhood. On most subscales, the lowest mean rank was observed for married inmates. Significant differences were observed between married and unmarried (

p = 0.005) and widowed (

p = 0.034) inmates. No significant differences in scores were observed between inmates with children and those without children.

In terms of residential environment, Mann–Whitney U tests showed that inmates from a rural environment have significantly higher mean ranks for the STO (U = 20,341.00, p = 0.004) and IIC (U = 20,576.00, p = 0.006) scores compared to inmates from an urban environment.

In terms of drug use (

Table 6), it was observed that on all five subscales, inmates who reported being drug users had higher mean ranks than inmates who were not drug users. Mann–Whitney U tests indicated that these differences are significant for the NOE, FAR, STO, NATA, and CCS-TS scores at a significance level of

p = 0.05.

Lastly, in terms of inmates’ perception of the justness of their punishment (

Table 7), for the IIC, NATA, and CCS-TS scores, Mann–Whitney U tests showed significant differences between inmates who thought that they had received a just sentence and those who did not. On all subscales, scores were higher for those who did not perceive the punishment received as just.

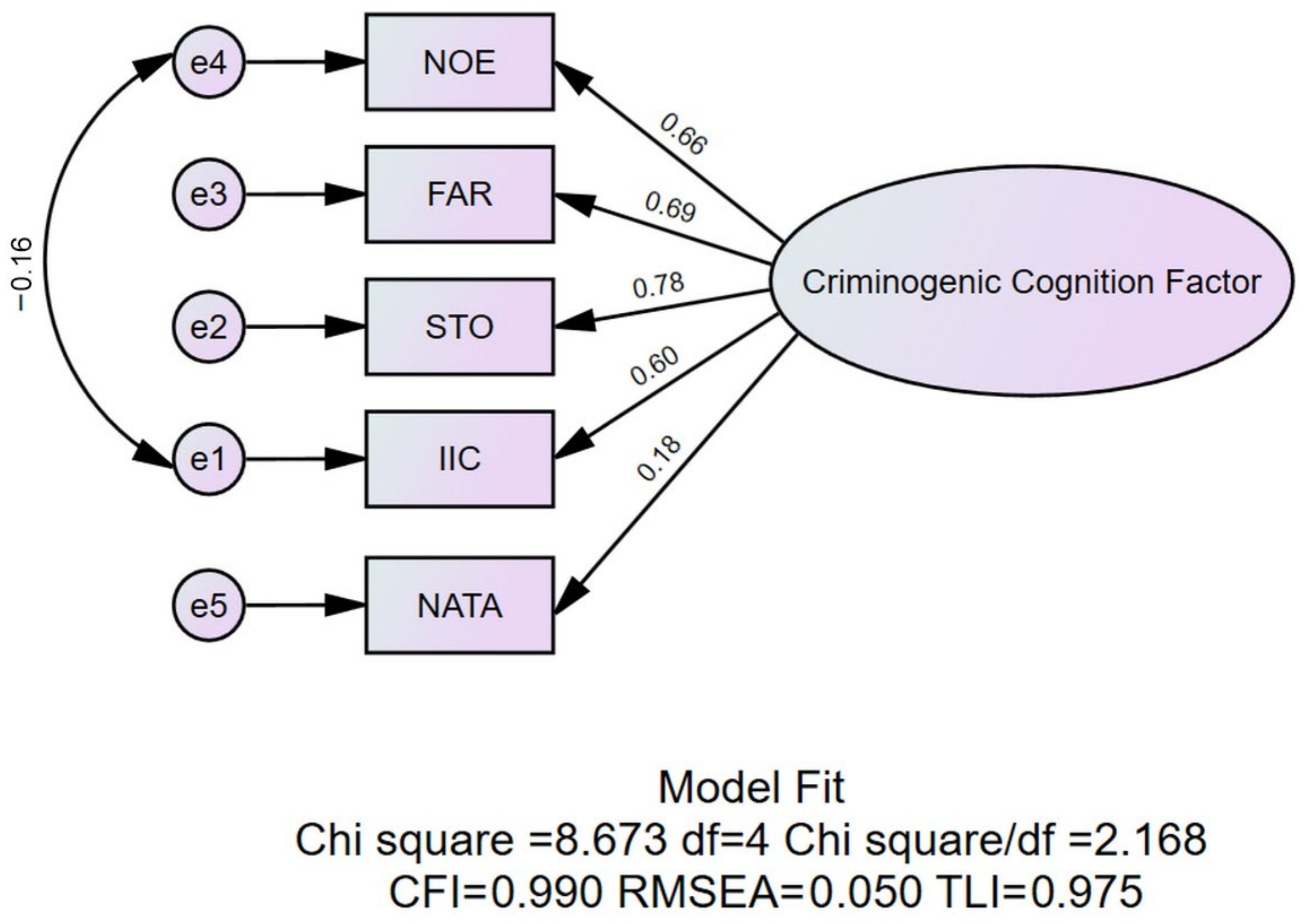

Dinal analysis of the general model proposed by

Tangney et al. (

2012) through a CFA in Amos (

Arbuckle 2019), for which the observed variables were the five scores calculated for NOE, FAR, STO, IIC, and NATA, indicated that the model adapted to the data from the Romanian sample is particularly successful. Based on the indicators

CFI = 0.990 > 0.950,

TLI = 0.975 > 0.950,

RMSEA = 0.050 < 0.08 and the Bollen–Stine test by bootstrap with 200 iterations, which indicated a significance level of

p = 0.119, we did not reject the null hypothesis that the model is a very good fit. The model is presented below in

Figure 1.

It was observed that the total standardized effect (direct and indirect) of the criminogenic factor on the NATA score was the smallest at 0.18. In other words, due to the direct (unmediated) and indirect (mediated) effects of the criminogenic factor on NATA, when the factor increases by one standard deviation, the NATA score increases by 0.18 standard deviations.

4. Discussion

4.1. Criminogenic Cognition in Sexual Offenders

The data analysis found that there was a predisposition to criminogenic cognition in prisoners convicted of sexual offenses. However, although the highest mean FAR scores were recorded for sex offenders, there remains an unresolved debate as to whether non-responsibility indicates a higher risk of committing sexual offenses.

Harkins et al. (

2015), based on a study conducted on a sample of 6891 sexual offenders, reported that lower levels of sexual recidivism were found for those who denied responsibility for their offense, independently of the static risk measured through a Cox regression analysis. Furthermore, when the latter analysis was performed, higher levels of violent recidivism among those denying responsibility proved to be insignificant. Likewise,

Ware and Mann (

2012) argued that the evidence that denial increases the risk of criminal recidivism is inconclusive. As for the reasons behind the failure to assume responsibility for sexual offenses, the phenomenon could be attributable to fear of negative extrinsic consequences and threats to the offender’s self-esteem and self-image (

Ware and Mann 2012).

At the same time, the fact that participants convicted of sexual offenses had the highest mean ranks for STO and IIC scores in the present study is in line with current theories about sexual offenders. Indeed, many authors who have dedicated their study to the personality traits of sexual offenders have noted that they exhibit a preference for immediate sexual gratification as well as a tendency to downplay their offense and low empathy (

Ward et al. 1995;

Pedneault et al. 2017;

Ward et al. 2006;

Saladino et al. 2021).

In addition, in some societies, there may be norms that normalize or minimize violence against women or other vulnerable groups. These norms could influence the thinking of aggressors, leading them to consider their actions as acceptable (

McAlinden 2019). Given the low consistency of Insensitivity to the Impact of Crime scale, additional studies are needed to clarify these aspects in sexual offenders.

4.2. Criminogenic Cognition Across Penitentiaries

The data of this study revealed the variability of criminogenic cognitions, depending on the specifics of the penitentiary unit of custody. To elucidate the differences found between the STO and CCS-TS scores in different penitentiaries, the differences in the levels of socio-economic development of the areas from which the offenders in the present batch originate (and which determine the penitentiary unit to which they are assigned) must be taken into account. According to Decision no. 360 of 28 February 2020 on the profiling of places of detention subordinated to the National Administration of Penitentiaries, inmates of the Bistrița Penitentiary are residents of Bistrița-Năsăud and Cluj counties, whereas inmates of the Vaslui Penitentiary are residents of Vaslui, Iași, Bacău and Vrancea counties (

Ministerul Justiției Administrația Națională a Penitenciarelor 2020). Thus, the Bistrița Penitentiary enforces custodial sentences ordered for residents of the northwestern region, considered to be one of the most developed in Romania, whereas the Vaslui Penitentiary enforces custodial sentences ordered for residents of the northeastern region, considered to be the poorest in the country (

Institutul Național de Statistică 2020,

2021).

The lower level of development of the northeastern region could be a contributing factor to a certain criminogenic cognition profile. In the region of Moldova, where the school dropout rate is high (

Peticilă 2020), along with the alcohol consumption rate (

Străuț 2015), alcohol-related violent crimes, e.g., homicide, have a high incidence. Meanwhile, in the northwestern region, different criminal trends are observed; in particular, there is a higher prevalence of offenses such as driving without a license, illegal tree felling, and smuggling.

Therefore, prisons could influence the criminal thinking of prisoners, both through their exposure to other criminals and through their living conditions. An under-resourced, overcrowded, and uninvolved detention unit could play a major role in maintaining criminal thinking. At the same time, it should not be overlooked that the quality of reintegration programs can vary from one prison to another, depending on the staff that organizes them. Therefore, many prisoners do not benefit from the support necessary to change their thinking and behavior.

4.3. Criminogenic Cognition About the Residential Environment

The differences between the FAR, STO, IIC, and CCS-TS scores depending on education level found in the present study agree with the results reported by

Tangney et al. (

2012), who identified a moderate negative correlation between years of education and CCS scores.

The significantly lower scores recorded for married inmates on the FAR subscale could be related to the social support that they have been receiving during their incarceration. According to

Jiang et al. (

2005), consistent social support fosters an altruistic mindset and social and family responsibility in inmates.

The significantly higher mean ranks recorded for inmates from a rural environment on the STO and IIC subscales could be accounted for by their lower income level. As data from the National Institute of Statistics of Romania shows, the incomes of rural residents are lower on average than those of urban residents (

Moldoveanu et al. 2015). The findings of the present study support the results reported by

Tangney et al. (

2012), who found a moderate negative correlation between CCS scores and pre-incarceration income.

Criminal thinking is influenced by the environment and individual factors such as education, family background, and socio-economic conditions. Unemployed people may be more likely to commit crimes (

Detotto and Pulina 2013).

In addition, limited access to education may contribute to criminal thinking. People with low levels of education may have less knowledge about the legal consequences of their actions or may have difficulty finding legitimate jobs (

Hjalmarsson et al. 2015).

4.4. Criminogenic Cognition Concerning Inmate-Reported Drug Use

The variability in the mean scores depending on drug use found in the present study is partly in agreement with the results of prior research, which indicates associations between drug use and individual scales only and not between drug use and CCS-TS scores.

Tangney et al. (

2012) notably identified a highly significant positive correlation (

p < 0.01) between FAR scores and drug problems, as well as the frequency of marijuana, cocaine, opiate, and polydrug use. The same study indicates a highly significant positive correlation between STO scores and drug problems and the frequency of polydrug use, and between NATA scores and the frequency of marijuana and opiate use. Additionally,

Petry (

2001) has observed an association between substance abuse and impulsiveness, noting a preference among drug users in the sample for immediate gratification.

Tangney et al. (

2012) have also established significant positive correlations between FAR scores and the frequency of opiate use, between STO scores and the frequency of marijuana and cocaine use, and between NATA scores and the frequency of polydrug use. The present study adds to their results by also demonstrating a significant correlation between NOE scores and drug use. The relationship between entitlement and drug use has previously been highlighted in a study conducted by

Tyler et al. (

2017) on a sample of 1482 US college students. The authors found that engagement in more drug-related risk behaviors was associated with higher scores on the Psychological Entitlement Scale. Drugs can alter the perception of reality, affecting the ability to judge situations correctly. This can lead to impulsive or risky behaviors, including criminal acts. Drugs can also reduce social and moral inhibitions, which can again lead to a greater predisposition to commit illegal acts (

Facchin and Margola 2016).

However, a study conducted in the US on a sample of 50 drug-using offenders attending a drug rehabilitation program did not detect a significant correlation between current drug use and entitlement scores (

Packer et al. 2009).

Although in the present study on Romanian offenders the relationship between drug use and criminogenic cognitions was significant across all five subscales, further research is needed to clarify the nature and consistency of this association, taking into account the context, the specific characteristics of the studied population, and other potential intervening factors.

4.5. Criminogenic Cognition in Relation to Perceived Justness of Punishment

The higher IIC, NATA and CCS-TS scores recorded for participants of the present study who considered their punishment to be unjust matched our expectations and are consistent with prior research in the field of criminal justice, which has suggested that when people feel that authorities are treating them fairly and respectfully, they are more likely to comply with decisions by such authorities (

Beijersbergen et al. 2015). Conversely, the perception of one’s punishment as unjust can trigger a series of psychological mechanisms conducive to an increased risk of future crime (

Sherman 1993).

Cherrington (

2007) explains that an overly mild punishment will be ignored by recipients, whereas an overly harsh one will lead to recipients focusing on the distress caused by it rather than on how they need to change their behavior to avoid being punished in the future.

Therefore, a punishment that is perceived as severe and certain can deter individuals from committing crimes. Rational choice theory suggests that people weigh the costs and benefits of their actions, and a large punishment can be a deterrent. On the other hand, if individuals perceive punishment as ineffective or unequal, it can normalize criminal behaviors (

Cornish and Clarke 2017).

4.6. Study Limitations

This preliminary validation of the Criminogenic Cognitions Scale in a Romanian sample represents an important step toward understanding cognitive patterns associated with criminal behavior in this cultural context. While the initial findings are promising, they highlight the need for further empirical research to confirm the scale’s reliability and validity. Cross-cultural adaptation is essential to ensure that the items accurately reflect the socio-cultural realities of Romanian respondents. Future studies should include larger and more diverse samples, as well as employ longitudinal designs to assess predictive validity over time. Such efforts will contribute to the development of effective assessment tools that can be used in both research and forensic practice.

The first limitation stems from the granting of credits to inmates for their voluntary participation in the study, as this form of compensation may generate a motivational distortion effect, affecting both their willingness to participate and the authenticity and quality of the responses provided

Although the sample size was adequate for conducting Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), it was not representative of the general Romanian population. Participants were likely selected based on convenience sampling, which limits the generalizability (invariance) of the results to other sociodemographic groups (e.g., age, education level, geographical region).

Subscales such as NATA and IIC showed low internal consistency values (Cronbach’s alpha < 0.6), which may indicate weak internal coherence of the items. The RMSEA values exceeding the acceptable threshold of 0.08 in some cases (e.g., NATA, NOE) suggest a less-than-optimal model fit to the empirical data.

Each CCS dimension included only five items, which may negatively affect the psychometric reliability, especially in short-form assessments. A low number of items limits the scale’s capacity to fully capture the complexity of the construct being measured. Some items (e.g., from the NATA subscale) were reverse-coded, which may lead to response errors or misinterpretations by participants, especially if the questionnaire lacked sufficient clarity.

CFA was conducted using estimators suitable for categorical data (WLSMV in lavaan), yet this type of analysis relies on statistical assumptions that, if not fully met, may affect the accuracy of the results.

Although cultural adaptation was attempted, not all psychological concepts from the original model necessarily have equivalent meanings for Romanian respondents, due to subtle cultural differences regarding guilt, responsibility, and forgiveness.

5. Conclusions

The results confirm the first hypothesis, indicating that the Criminogenic Cognitions Scale demonstrates moderate validity among inmates in Romanian penitentiaries. Although the factorial structure aligns with the original model (

Tangney et al. 2012), internal consistencies vary: only the FAR subscale exhibits high reliability, NOE and STO reach acceptable levels, whereas IIC and NATA fall below the recommended threshold. Consequently, the scale should be employed as a complementary instrument in the assessment of criminogenic cognitive profiles, necessitating integration with other psychological measures and, in particular, with qualitative exploration through interviews, to gain a deeper understanding of the meanings inmates attribute to the items of the Insensitivity to the Impact of Crime and Negative Attitudes Toward Authority subscales, as well as to minimize potential socially desirable responses elicited by the specific context of the penitentiary environment.

The second hypothesis was confirmed: certain socio-demographic variables and psychological factors have an impact on the dimensions of criminogenic cognitions.

The analysis of the CCS scores concerning the specifics of the source penitentiary unit highlighted significant differences. The highest values were recorded for subjects who came from Vaslui Penitentiary, and the lowest were associated with subjects detained at Bistriţa Penitentiary. An explanation for this can be found in the specifics of the criminal category to which the respective subjects belong and by the impact that the prison as an organization exerts on the behavior of the persons in custody, as well as by sociocultural influences. Thus, it is expected that there will be differences regarding the dimensions of criminogenic thinking depending on the act committed; this has been validated by the current study. Regarding the impact of the unit, aspects related to the execution regime under which the custodial sentence is carried out should not be omitted, such as the possibility of carrying out gainful activities outside or inside the place of detention, benefiting from permits, having an established route for movement that does not require guarding, and participating in social activities outside the place of detention. At the same time, regarding the variability in criminogenic cognitions, the attitude of the staff, regardless of their level of involvement, as well as the number of staff necessary to cover the needs of specialized interventions, should be taken into account. All these aspects can have a major role in the offender’s cognition. Regarding the socio-cultural environment, the explanation is also supported by the present study, with the results demonstrating that the typology of criminogenic cognition varies depending on educational level, marital status and residential environment.

It was found that a high level of education positively contributes to the acceptance of authority and the ability to determine long-term goals and realize the consequences of a crime. However, it should be noted that the level of education is linked to the environment of residence. Rural environments, in most cases, imply more limited possibilities for enrolling in education; the results emphasize the need to develop rural environments from a socio-economic and educational perspective as a result of this. At the same time, the present study identified that the institution of marriage exerts a positive influence in terms of assuming responsibilities, an aspect that seems to be confirmed by the fact that widowed prisoners recorded the highest average rank for the FAR scale.

The analysis of CCS scores about the type of crime also identified significant differences. The lowest average ranks were observed for financial crimes, and the highest average ranks for sexual crimes. These data led to the conclusion that prisoners convicted of sexual offenses may have a higher risk of criminal recidivism, a particularly important aspect in the intervention of forming a healthy cognitive map against sexual abuse, sexual exploitation, sexual harassment, child pornography, and human trafficking.

The analysis of CCS scores concerning the drug use variable highlighted the overwhelming impact of illicit substance use on the cognitive capacities of individuals, as well as on the changes that their personality structure undergoes over time. Overall, drug use is one of the major factors contributing to crime and one that requires specialized attention.

CCS scores with the significance given to the duration of the sentence established by the legislator were higher in prisoners who perceived that the punishment received was unfair. The findings indicate that punishment alone does not ensure offender reform; understanding the offender’s cognitive framework regarding the act, the victim, and the sentence is essential. The results show a reciprocal reinforcement between criminogenic thinking and perceptions of punishment as unjust, which may foster hostility, distrust, and rationalizations that sustain or even encourage future criminal behavior.

It is also recommended that when implementing social reintegration programs in the penitentiary environment, the civil status, the specific nature of the criminal category, the history of addiction before conviction, and the general real attitude towards authority (in the penitentiary environment, prisoners can mimic a positive attitude towards authority) should be taken into account. In this regard, it is considered useful to implement activities that actively involve the prisoner’s family and facilitate maintained contact between them (physically or online). In addition, specialized interventions should focus on specific types of criminogenic cognitive distortions, as it is unlikely that recidivism will decrease if the individual does not take responsibility for their actions or does not show empathy toward the victims.

Campaigns on the impact of drugs may be particularly important, a proposal supported by the high scores on the scale observed among drug-using offenders, both for the urban population (where the risk of use is higher) and for the rural population (where information is less accessible).

Despite its limitations, this study, conducted on a sample of Romanian inmates, provides a foundation for future research aimed at refining the understanding of Criminogenic Cognition Profiles and informing the development of more effective rehabilitation interventions.