“That She Is Unique Is Clear”: Family Members Making Sense of the Uniqueness of Persons with Dementia and Persons with Profound Intellectual and Multiple Disabilities

Abstract

1. Introduction

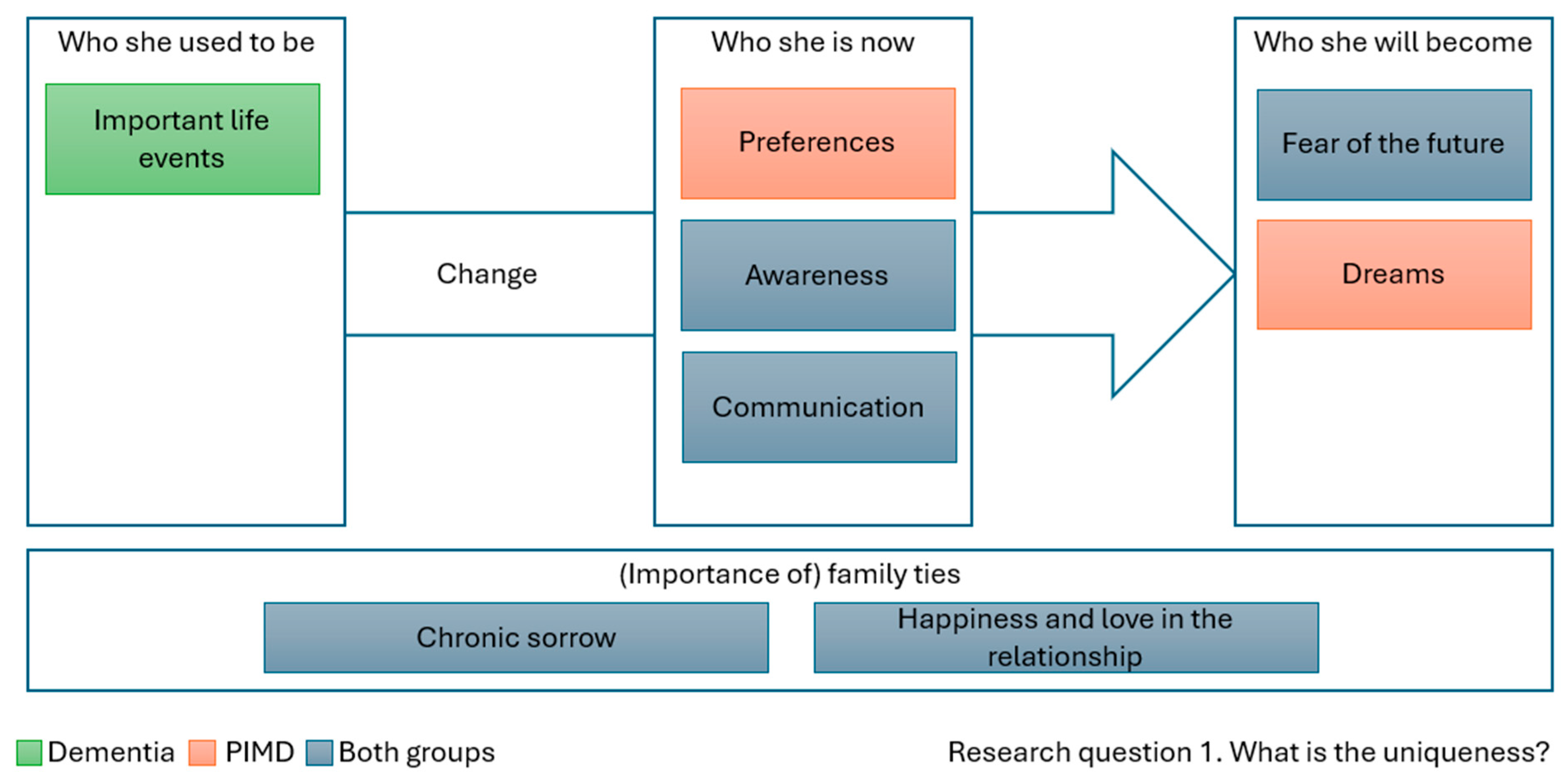

- What is, according to family members, the uniqueness of the person with high-support needs?

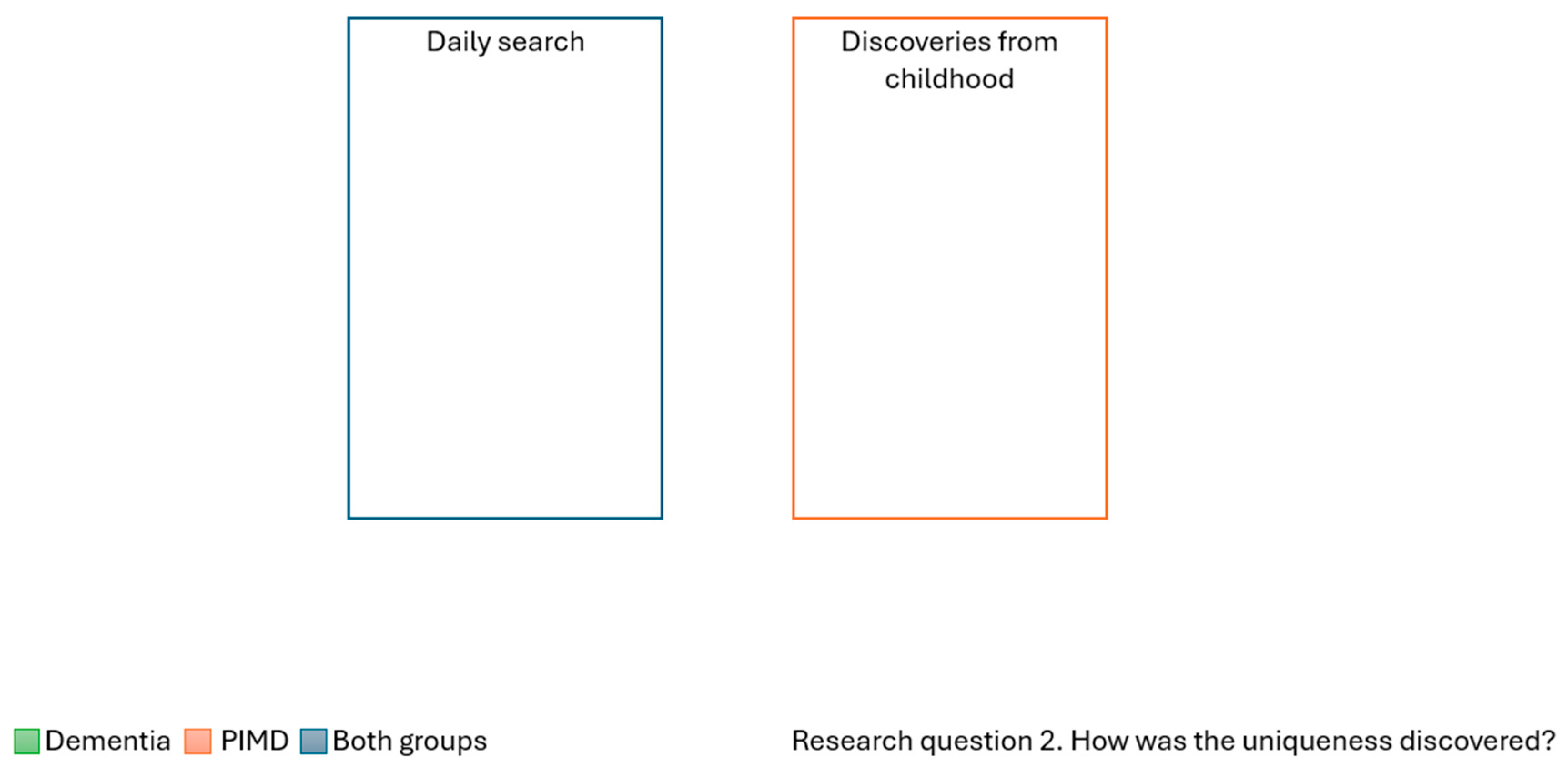

- How has this uniqueness been discovered?

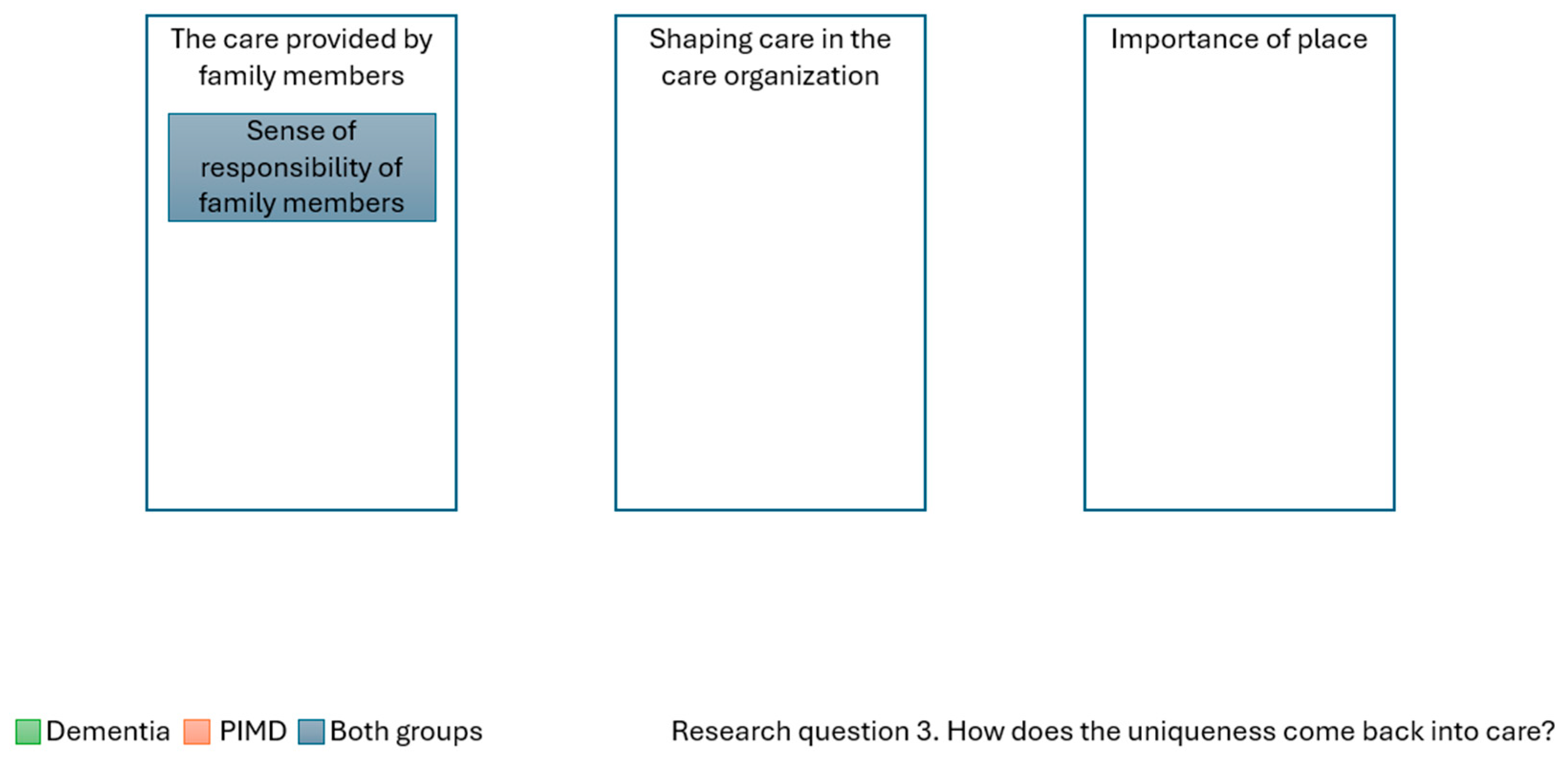

- How does this uniqueness come to the fore in the care situation?

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Research Question 1: What Is the Uniqueness of Persons with High Support Needs?

3.1.1. Who She Used to Be (D1, D2, D3, P5, P6)

No outlier, neither to the low nor to the high. How should I put it? Of uh… not that you say ooh that’s a smart one or that was a uh…, yeah, very ordinary, loving mum.(D2)

(Researcher:) And you’ve mentioned the family several times now and so on. Is that important to her?

(Participant:) That was important eh. Family was important.(D1)

Yes. He died then yes. But… always thinking about… yes. About his wife eh. Yes. We always said he’s going to take care of her until he collapses, that’s what they say here. And… it was like that. It was like that. Yes. And now it’s our turn to do our bit.(D1)

Yes, then she decided eh. Also told my father, look, I’m going to live in [place]. They lived a bit further here, a few kilometers. But in those days, it was a lot of those same-aged people, 55 is still a bit young, but those people started about my house being too big, I’m going quietly to the city, we can get a little flat, short to everything, and then she said I’m going to live in a little flat. My dad thought ah yes, where? He thought together eh. Then she said I’m going to live there alone. Uh… Yes, then they… Did they break up heh.(D2)

3.1.2. Change (D1, D2, D3, P5, P6)

Before, she was not in the wheelchair and then in a small one and then she was in the big wheelchair. She couldn’t even swallow anymore. She was very crooked, no longer swallowing, uhm… but at two months my mother had gone from dementia stage one to stage four in my eyes.(D2)

(Researcher:) Can you tell me more about who [name wife] is? (Participant:) Whew. How am I supposed to do that? I have, yes, in the last ten years, what should I say, more than ten years… Yes, now it’s about twelve years ago that I… that all that started, so uh… that I didn’t have a grip on her anymore, on [name wife] as I used to know her. At night she got up at two o’clock. Then she went out into the street. I’ll never forget it during carnival. 2017 was that time. I was so scared eh.(D3)

Uhm… We used to take her everywhere. We have the impression, in the last few years, that’s become a bit more difficult. That she needs more sleep, uhm… That, that the rhythm of the day sometimes becomes more challenging.(P6)

3.1.3. Who She Is Now (D1, D3, P4, P5, P6)

The shell is still my mother, and I can still see in her eyes that she is my mother, but that is actually all I see of my mother.(D2)

Yes, that she is unique is clear, so uhm… [Researcher:] Why is that clear? [Participant:] Yes, hahaha. I don’t think there are many… With that syndrome, there aren’t many people. So yes, she is different from the other residents. The others can do much more. She is the only one who really needs all that support.(P5)

Uh… we place quite a bit of importance on, yes, that she is well-dressed, that her hair is nicely groomed, that she herself is well-groomed. Uhm… there’s a joke in the family that my grandmother thought it was important for us to wear earrings, things like that. And yes, from a young age, it was the same with [name daughter], and she received many compliments about it. Wow, [name daughter], you are beautiful. Now, she is also a beautiful girl. Uhm… yes, she loved that, and now you can see that she still likes nice clothes and such.(P6)

Yes, whether she really enjoys it, we never know. Whether she really likes it, yes, she just goes along with everything.(P4)

Shall we go for a walk? She says walk. Then uh… I take her to the next big building, uh…, the lounge there, I sit down. She sits next to me, sleeping. Occasionally, she lifts her head and looks at me, then she smiles and then [he pretends to sleep]. Otherwise, I leave her alone, you know. Because you can’t make contact with her at that moment, and then yes, she just lies there. Always sleeping, sleeping, sleeping.(D3)

So yes, those are the kinds of things where you see, hmm, she does realize more… and those moments when everyone is a bit sad, she is also a bit more tense. Like, what should I say? She seems to feel it too. Yes, like, she was, yes, she was a bit resistant, that’s not well said, but yes, she felt that something was off. Those were the moments, that period, yes, that she wasn’t quite herself. How she used to be, you noticed… don’t ask me how, I don’t remember, but you noticed that she was a bit more angry and hmhmhmhm, yes, yes. Like that. Those kinds of things. So there are also moments when you know… something like okay, yes, they have feelings, but yes, what does she understand? So yes, but hahaha. Maybe also still… feelings, yes.(P4)

And she realizes very little. She has no self-image, [name daughter], with the problem around her limitations. On one hand, it’s sad how limited she is, but on the other hand, she is not unhappy because of her situation. We think she misses a lot, but she doesn’t know that. She doesn’t know that she, yes, is not mobile, that she can’t do things, that she can’t have a relationship, that she… she doesn’t know any of that. Does she have an image of us? We are familiar voices and familiar actions, but she doesn’t know what ‘mom’ is. She doesn’t know that. It’s a bit, yes, not to dwell on it too much, but she doesn’t actually know that.(P5)

Yes, she can still show some emotion, yes. She can wink, and she winks back so we have a little connection. Or sometimes I touch her hands, or place my hands against hers, and she responds a bit. But yes, my mother is still here. She is here, but she is not here anymore.(D2)

Yes, that gives… I also have an iPad for her, where I put photos on, because for me and her it’s a kind of communication tool. Through photos… you see certain things in photos. Then you can talk about them, like ‘Oh, did you swim here?’ or ‘Ah, did you do this here?’ And then, that creates communication. That, that, that creates words, whereas if you don’t know things or, yes, you can’t ask her. She can’t tell me and I can’t ask her if it’s not completely clear.(P6)

3.1.4. Who She Will Become (D1, D2, P5, P6)

Yes, I think, uhm… if she had been 100% mentally sound, she would have had more of my character. My wife is much calmer, much more tolerant. I can be quite a hothead sometimes. Uhm… I think she would have had some temperament. Yes, definitely. Energetic. She is also quite robustly built.(P5)

We always said, wow, if she had developed normally, that would have been… that would have been quite something. It would have been quite intense. There would have been some serious clashes, yes.(P6)

I am physically healthy, uh… Sometimes in the back of my mind, I hope I will never get it. But yes, if it happens, we will deal with it then. For now, we will just enjoy everything we have and do as much as possible.(D2)

Also, she needs to consider her surroundings. I find that important. Uhm… as long as we can provide care for her, it’s our choice what we give, but you know… here she has to live in a group, she also has to consider others. I always found that important, because you can do everything for her, but that’s not always good. She shouldn’t become spoiled, haha. I don’t want that.(P6)

3.1.5. (Importance of) Family Ties (D1, D2, D3, P4, P5, P6)

You saw that evolve. It hurts. It hurts. Because we also… our weekly outings together to the hairdresser and shopping for clothes, having a cup of coffee. And yes, enjoying life. That… you can’t do that anymore. … Yes.(D1)

Well, we had hoped for a normal family, I would say. Yes, that didn’t happen, well, it didn’t turn out that way. Not that I would complain about it, no, not at all. It is what it is, and I think we have all become stronger and wiser because of it. We might have more life experiences, so it’s good.(P4)

Yes, I say [name wife] is a wonderful person. Always been there for me and still is, because otherwise I wouldn’t keep coming, right? That’s how I see it. Yes. And she has always had a friendly smile. You haven’t seen her, have you?(D3)

3.2. Research Question 2: How Has the Uniqueness Been Discovered?

3.2.1. Daily Search (D1, P4)

Ah yes, satisfied. So you go and find out for yourself, right? If she starts crying or whining… You look to see what she does like, what she wants, and then you try things that you think, okay, that’s something… If there’s really something, like those little programs [points to the TV], I often turn it off and put something else on, because I don’t know if she understands it. Like, Bumba or something, she likes that. You can see that too, because then she laughs sometimes.(P4)

3.2.2. Discoveries from Childhood (P5, P6)

Uhm… she was an easy baby, but from the moment she started discovering the world, yes, she went her own way. Uh…, haha, because at home, you know, one of those little devices with wheels that they can sit in when they can’t walk yet, when they can’t crawl yet, so she could go everywhere. Yes, she went everywhere, that’s true, haha, that was fun. And once there was chocolate on the table, she [makes a grabbing motion]. Back then, she could still grab.(P6)

3.3. Research Question 3: How Does the Uniqueness Come to the Fore into Care?

3.3.1. The Care Provided by Family Members (D1, D2, D3, P4, P5, P6)

It didn’t get worse. But he wanted to change it spectacularly, there was a new medicine. And then she had one seizure after another, it was… yeah, she almost couldn’t get out of it. That was still during the COVID-19 period, we weren’t allowed in the house. Then we contacted the uh… GP here. Doctor [name doctor], who is also connected here. He’s a regular GP. Then we said look, it’s time for you to act, because uh… This can’t go on. This, this, this will end fatally. If we hadn’t acted, she wouldn’t be here anymore, I think. She would have gone into a status, so uh… a seizure you can’t get out of, which is then fatal. And that’s how it was.(P5)

Uh… it’s okay, it’s okay. I find it difficult, well, difficult, to distance myself like that. Yes. Sometimes I feel like those Tuesdays and Wednesdays are my days off, I can’t do anything else, well. Sometimes I feel like, ah, then I have to take her with me. Yes, that should actually be possible, then I should do it too, but yeah, sometimes you don’t always do that.(P4)

3.3.2. Shaping Care in the Care Organization (D2, P4, P5, P6)

She can be very… very out of it, I’ll say, and not understand who I am or anything, and then the nurse or the uh… caregiver will say, hmm, she’s been sleeping a lot today or she hasn’t eaten much. Uh… when I come, even if she doesn’t recognize me, she can really say no, no, but yeah, with the wheelchair you can move her around yourself and as soon as we’re on our way, I see that she really blossoms, that she really enjoys it… She really likes being in the cafeteria.(D2)

I’ve always known that if something were to happen to me and that child had to suddenly, from one day to the next, day in and day out, that wouldn’t be fun either. Okay, she will get used to it, but, but, no. Yes, we have always been able to…(P4)

3.3.3. Importance of Place (D1, P5)

That was also for us, the moment she was here for fifteen minutes, on [date], uhm… that she was already sitting there, we were already busy with the cupboard, and she was sitting in the common area, fussing. We thought, okay, then we can leave with peace of mind. Well, we hoped so, because yes, we know the staff now, so… a really nice group here, that too.(P5)

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buron, Bill. 2008. Levels of personhood: A model for dementia care. Geriatric Nursing 29: 324–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, Amy Louise, Adele Baldwin, and Clare Harvey. 2020. Whose centre is it anyway? Defining person-centred care in nursing: An integrative review. PLoS ONE 15: e0229923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crettenden, Angela, Annemarie. Wright, and Erin Beilby. 2014. Supporting families: Outcomes of placement in voluntary out-of-home care for children and young people with disabilities and their families. Children and Youth Services Review 39: 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Megan, Franziska Zúñiga, Hilde Verbeek, Michael Simon, and Sandra Staudacher. 2023. Exploring Interrelations Between Person-Centered Care and Quality of Life Following a Transition Into Long-Term Residential Care: A Meta-Ethnography. The Gerontologist 63: 660–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davy, Laura. 2019. Between an ethic of care and an ethic of autonomy: Negotiating relational autonomy, disability, and dependency. Angelaki: Journal of Theoretical Humanities 24: 101–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degnen, Cathrine, ed. 2018. The Making of Personhood. In Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Personhood and the Life Course. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haas, Catherine, Joanna Grace, Joanna Hope, and Melanie Nind. 2022. Doing research inclusively: Understanding what it means to do research with and alongside people with profound intellectual disabilities. Social Sciences 11: 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklund, Jakob Håkansson, Inger Holmstrom, Tomas Kumlin, Elenor Kaminsky, Karin Skoglund, Jessica Hoglander, Annelie Sundler, Emelie Conden, and Martina Summer Meranius. 2019. ‘Same same or different?’ A review of reviews of person-centered and patient-centered care. Patient Education and Counseling 102: 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagnon, Eric, and Romane Marcotte. 2025. On personhood in residential and long-term care centres. Journal of Aging Studies 72: 101308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjermestad, Anita. 2017. Narrative competence in caring encounters with persons with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. International Practice Development Journal 7: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakobyan, Liana, Anna P. Nieboer, Harry Finkenflugel, and Jane M. Cramm. 2020. The significance of person-centered care for satisfaction with care and well-being among informal caregivers of persons with severe intellectual disability. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 17: 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, Tamar, Hailee M. Gibbons, and Dora Fisher. 2015. Caregiving and Family Support Interventions: Crossing Networks of Aging and Developmental Disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 53: 329–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennelly, Niamh, and Eamon O’Shea. 2021. A multiple perspective view of personhood in dementia. Ageing and Society 42: 2103–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugo, Julie, and Mary Ganguli. 2014. Dementia and Cognitive Impairment Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 30: 421–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kittay, Eva Feder. 1999. Love’s Labor: Essays on Women, Equality, and Dependency. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kitwood, Tom. 1997. Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First. Buckingham: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kruithof, Kasper, Maartje Hoogsteyns, Ilse Zaal-Schuller, Sylvia Huisman, Dick Willems, and Appolonia Nieuwenhuijse. 2024. Parents’ tacit knowledge of their child with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities: A qualitative study. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability 49: 415–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindemann, Hilde. 2009. Holding one another (well, wrongly, clumsily) in a time of dementia. Metaphilosophy 40: 416–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann, Hilde. 2019. An Invitation to Feminist Ethics, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maes, Bea, Sara Nijs, Sien Vandesande, Ines Van keer, Michael Arthur-Kelly, Juliane Dind, Juliet Goldbart, Geneviève Petitpierre, and Annette Van der Putten. 2021. Looking back, looking forward: Methodological challenges and future directions in research on persons with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 34: 250–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manthorpe, Jill, and Kritika Samsi. 2016. Person-centered dementia care: Current perspectives. Clinical Interventions in Aging 11: 1733–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieuwenhuis, Sanne, Amber De Coen, Sara Nijs, and Bea Maes. 2025. Understanding Personhood of People with Profound Intellectual and Multiple Disabilities and People with Dementia: A Concept Mapping Study. Leuven: KU Leuven. [Google Scholar]

- Skarsaune, Synne Kristin Nese. 2023. Learning from Persons with Profound Intellectual and Multiple Disabilities: An Ethnographic Study Exploring Self-Determination and Ethics of Professional Relations. Ph.D. dissertation, VID Specialized University, Oslo, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Jamie B., Eva-Maria Willis, and Jane Hopkins-Walsh. 2022. What does person-centred care mean, if you weren’t considered a person anyway: An engagement with person-centred care and Black, queer, feminist, and posthuman approaches. Nursing Philosophy 23: e12401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, Jonathan Alan, Paul Flowers, and Michael Larkin. 2009. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Spiers, Johanna, and Jonathan Alan Smith. 2019. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Newcastle upon Tyne: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tieu, Matthew, Alexandra Mudd, Tiffany Conroy, Alejandra Pinero de Plaza, and Alison Kitson. 2022. The trouble with personhood and person-centred care. Nursing Philosophy 23: e12381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vehmas, Simo, and Reetta Mietola. 2021. Narrowed Lives: Meaning, Moral Value, and Profound Intellectual Disability. Stockholm: Stockholm University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Andrea, Jessica Bell, Jenna Locke, Ashley Roach, Anita Rogers, Evan Plys, Dalit Zaguri-Greener, Anna Zisberg, and Ruth P. Lopez. 2024. Family Involvement in the Care of Nursing Home Residents with Dementia: A Scoping Review. Journal of Applied Gerontology 43: 1772–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participant | Respondent | Family Member with PIMD/Dementia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Gender | Relationship | PIMD or Dementia | Age | Gender | Additional (Medical) Problems | Years Residing in Current Care Organization | |

| 1D | 65 | Female | Daughter | Dementia | 91 | Female | Problems with motor skills | 5 |

| 2D | 61 | Female | Daughter | Dementia; Alzheimer’s disease | 85 | Female | Problems with motor skills | 6 |

| 3D | 85 | Male | Husband | Dementia | 83 | Female | Problems with motor skills, small decline in hearing | 5 |

| 4P | 50 | Female | Mother | PIMD; Rett syndrome | 28 | Female | Problems with motor skills, epilepsy | 5 |

| 5P | 65 | Male | Father | PIMD | 34 | Female | Problems with motor skills, hemiplegic, epilepsy, blind | 3 |

| 6P | 55 | Female | Mother | PIMD; Rett syndrome | 25 | Female | Problems with motor skills | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nieuwenhuis, S.; Vandesande, S.; Nijs, S.; Maes, B. “That She Is Unique Is Clear”: Family Members Making Sense of the Uniqueness of Persons with Dementia and Persons with Profound Intellectual and Multiple Disabilities. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 546. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090546

Nieuwenhuis S, Vandesande S, Nijs S, Maes B. “That She Is Unique Is Clear”: Family Members Making Sense of the Uniqueness of Persons with Dementia and Persons with Profound Intellectual and Multiple Disabilities. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(9):546. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090546

Chicago/Turabian StyleNieuwenhuis, Sanne, Sien Vandesande, Sara Nijs, and Bea Maes. 2025. "“That She Is Unique Is Clear”: Family Members Making Sense of the Uniqueness of Persons with Dementia and Persons with Profound Intellectual and Multiple Disabilities" Social Sciences 14, no. 9: 546. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090546

APA StyleNieuwenhuis, S., Vandesande, S., Nijs, S., & Maes, B. (2025). “That She Is Unique Is Clear”: Family Members Making Sense of the Uniqueness of Persons with Dementia and Persons with Profound Intellectual and Multiple Disabilities. Social Sciences, 14(9), 546. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090546