From Bystander Silence to Burnout: Serial Mediation Mechanisms in Workplace Bullying

Abstract

1. Introduction

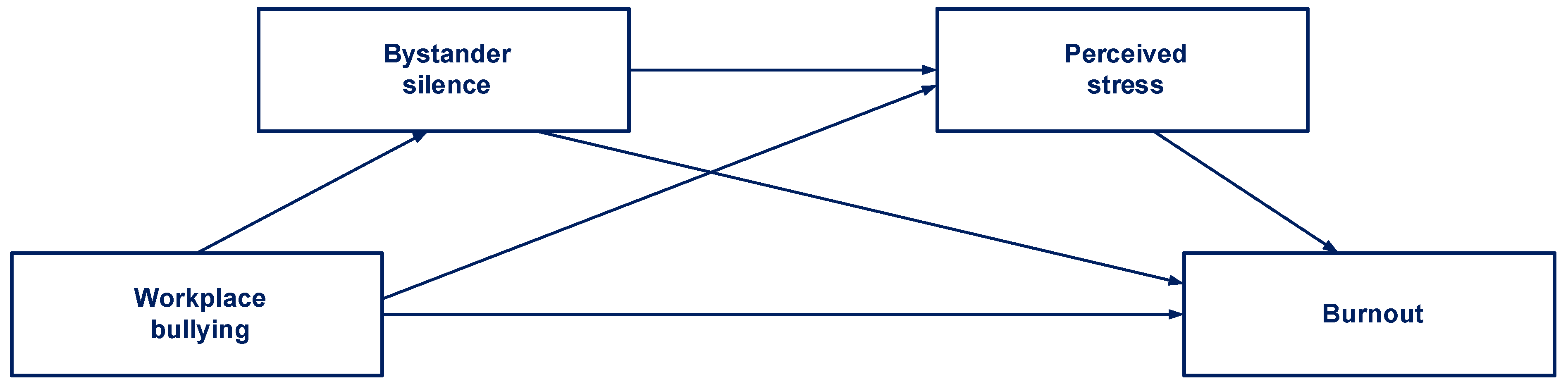

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) Model

2.2. Workplace Bullying as a Job Demand

2.3. Bystander Silence as a Resource Depletion

2.4. Perceived Stress as a Cognitive-Affective Appraisal

2.5. Burnout as a Strain Outcome

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measurement

- Exposure to workplace bullying: A single-item self-labeled measure proposed by Einarsen and Skogstad (1996) is used. The self-labeling method is where respondents are given a formal definition (see Einarsen et al. (2011) in the theoretical background) of bullying and then asked whether they consider themselves bullied. The item is “Have you been subjected to bullying at work during the last six months?” The response alternatives ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (daily). Only participants rated 4 and 5 were included in the study. In other words, individuals who perceive themselves as subjected to bullying weekly or daily.In a preliminary pilot study, 30 bilingual participants completed the English version of the scale and, one week later, the Turkish version. The correlation between the two administrations was r = 0.77, indicating satisfactory test–retest reliability. The self-labeling method can introduce bias and therefore needs to be used in conjunction with a workplace bullying scale (Nielsen et al. 2020).

- Workplace bullying: The workplace bullying score was calculated using a validated bullying scale inspired by instruments developed by Leymann (1996a, 1996b) and Neuman and Keashly (2004). The scale, composed of 30 items, was designed to evaluate the nature and severity of workplace bullying. It measures five subdimensions: (1) Target’s communication: Assessing instances where the target is prevented from expressing themselves (e.g., being interrupted or not listened to). (2) Target’s maintaining social contacts: Evaluating experiences of social isolation (e.g., not being talked to or excluded from meetings). (3) Target’s personal reputation: Investigating occurrences of gossip or defamatory remarks about the target. (4) Target’s occupational reputation: Exploring experiences such as task deprivation or withholding of assignments. (5) Target’s physical health: Assessing threats of physical harm, such as injury or assault. Example items: “How often have you been prevented from expressing yourself (interrupting your speech, not being listened to)?” “How often have you been ostracized from your work environment (not being talked to, not being invited to meetings)?”The instrument demonstrated high internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 86, indicating its reliability. Previous research (e.g., Minibas-Poussard et al. 2022) has validated the scale through factor analysis, with all subscales exhibiting factor loadings ≥ 0.30 and the Cronbach’s alpha being 0.85.

- Burnout: The short version of The Pines (2005) scale is used. This ten-item scale has been validated in previous research for Turkish people with a high Cronbach alpha of 0.91 (Tümkaya et al. 2009). Example items: “I feel helpless.” “I feel emotionally drained.” In the current study, the psychometric properties are satisfactory (factor load ≥ 0.40 and Cronbach alpha: 0.87).

- Bystander silence: A scale of 5 items was developed, inspired by studies of Paull et al. (2012). The scale shows satisfactory psychometric properties (factor load ≥ 0.40 and Cronbach alpha: 0.90). Example items: “When I was bullied, people around me turned a blind eye.” “Nobody even wanted to talk about what happened.”

- Perceived stress: Developed by Cohen et al. (1983), the scale is based on Lazarus and Folkman (1984)’s concept of cognitive stress. It contains 10 items and shows satisfactory psychometric properties (factor load ≥ 0.40 and Cronbach alpha: 0.79). Example items: “How often have you felt nervous and stressed?” “How often have you been angered because of things that happened that were outside of your control?”

4. Results

4.1. Bullying Behaviors and Their Frequency

4.2. Mediation Analyses

5. Discussion

6. Practical Implications

7. Limitations and Directions for Future Directions

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | The World Health Organization |

| ICD-11 | 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases |

| JD-R | Job Demands-Resources |

References

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Evangelia Demerouti. 2007. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology 22: 309–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, Danielle, Anna Toropova, and Christina Björklund. 2024. Workplace bullying, stress, burnout, and the role of perceived social support: Findings from a Swedish national prevalence study in higher education. European Journal of Higher Education 15: 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomberg, Stefan, Stale V. Einarsen, and Michael Rosander. 2025. Conflict management climate and the prevention of workplace bullying: A multi-cohort three-wave longitudinal study. International Journal of Conflict Management 36: 841–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, Richard W. 1986. The wording and translation of research instruments. In Cross-Cultural Research and Methodology Series, 8. Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research. Edited by Walter. J. Lonner and John W. Berry. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 137–64. [Google Scholar]

- Civilidag, Aydın. 2015. Farklı örgütsel yapiılarda işyerinde psikolojik tacizin (mobbing) yaygınlığı, önlenmesi ve cinsiyet değişkeni üzerine nitel bir analiz. Dumlupınar Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi 46: 118–47. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Sheldon, Tom Kamarck, and Robin Mermelstein. 1983. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 24: 385–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, Paul Maurice, Annie Høgh, Cristian Balducci, and Denis Kiyak Ebbesen. 2021. Workplace bullying and mental health. In Pathways of Job-Related Negative Behaviour. Edited by Premilla D’Cruz, Ernesto Noronha, Elfi Baillien, Bevan Catley, Karen Harlos, Annie Høgh and Eva Gemzøe Mikkelsen. Singapore: Springer, pp. 101–28. [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti, Evangelia, Arnold B. Bakker, Friedhelm Nachreiner, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2001. The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology 86: 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detert, James R., and Amy C. Edmondson. 2011. Implicit voice theories: Taken-for-granted rules of self-censorship at work. Academy of Management Journal 54: 461–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, Stale, and Anders Skogstad. 1996. Bullying at work: Epidemiological findings in public and private organizations. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 5: 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, Stale, Helge Hoel, Dieter Zapf, and Cary L. Cooper. 2011. The concept of bullying and harassment at work: The European tradition. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace. Developments in Theory, Research, and Practice, 2nd ed. Edited by Stale Einarsen, Helge Hoel, Dieter Zapf and Cary L. Cooper. London: Taylor & Francis, pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Einarsen, Stale V., Helge Hoel, Dieter Zapf, and Cary L. Cooper. 2020. The concept of bullying and harassment at work: The European tradition. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace. Developments in Theory, Research, and Practice, 3rd ed. Edited by Stale Einarsen, Helge Hoel, Dieter Zapf and Cary L. Cooper. Boca Raton: CRC Press, pp. 3–53. [Google Scholar]

- Esnard, Catherine, and Martine Roques. 2014. Collective efficacy: A resource in stressful occupational contexts. Revue Européenne de Psychologie Appliquée 64: 203–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, Samuel, Daniella Mokhtar, Kara Ng, and Karen Niven. 2023. What influences the relationship between workplace bullying and employee well-being? A systematic review of moderators. Work & Stress 37: 345–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, Petros, Ioannis Moisoglou, Aglaia Katsiroumpa, and Panayota Sourtzi. 2024. Impact of workplace bullying on job burnout and turnover intention among nursing staff in Greece: Evidence after the COVID-19 pandemic. AIMS Public Health 11: 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgi, Gabriele, Giulio Arcangeli, Milda Perminiene, Chiara Lorini, Antonio Ariza-Montes, Javier Fiz-Perez, Annamaria Di-Fabio, and Nicola Mucci. 2017. Work-related stress in the banking sector: A review of incidence, correlated factors, and major consequences. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 21–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gok, Sibel. 2011. Prevalence and types of mobbing behavior: A research on banking employees. International Journal of Human Sciences 8: 318–34. [Google Scholar]

- Grynderup, Matias B., Kirsten Nabe-Nielsen, Theis Lange, Paul M. Conway, Jens P. Bonde, Laura Francioli, Anne H. Garde, Linda Kaerlev, Reiner Rugulies, Marianne A. Vammen, and et al. 2016. Does perceived stress mediate the association between workplace bullying and long-term sickness absence? Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 58: 226–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogh, Annie, Ase M. Hansen, Eva G. Mikkelsen, and Roger Persson. 2012. Exposure to negative acts at work, psychological stress reactions and physiological stress response. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 73: 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, Kristoffer, Sandra Jönsson, and Tuija Muhonen. 2022. Witnessing Workplace Bullying: Antecedents and Consequences related to the Organizational Context of the Health Care Sector. Paper presented at the 13th International Association on Workplace Bullying and Harassment Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, September 20–24; pp. 87–88. [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson, Sandra, and Tuija Muhonen. 2022. Factors influencing the behavior of bystanders to workplace bullying in healthcare—A qualitative descriptive interview study. International Journal of Human Sciences 45: 424–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Yujeong, Eunmi Lee, and Hayoung Lee. 2019. Association between workplace bullying and burnout, professional quality of life, and turnover intention among clinical nurses. PLoS ONE 14: e0228124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, Heather K.S., and Roberta Fida. 2014. A time-lagged analysis of the effect of authentic leadership on workplace bullying, burnout, and occupational turnover intentions. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 23: 739–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latané, Bibb, and John M. Darley. 1970. The Unresponsive Bystander: Why Doesn’t He Help? Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, Richard. S., and Susan Folkman. 1984. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Leymann, Heinz. 1996a. La Persécution au Travail [The Persecution at Work]. Paris: Editions du Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Leymann, Heinz. 1996b. The content and development of mobbing at work. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 5: 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutgen-Sandvik, Pamela. 2003. The cycle of employee emotional abuse: Generation and regeneration of workplace mistreatment. Management Communication Quarterly 16: 471–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, Christina, and Michael P. Leiter. 2016. Burnout. In Stress: Concepts, Cognition, Emotion, and Behavior. Edited by George Fink. Cambridge: Academic Press, vol. 1, pp. 351–57. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, Christina, and Susan E. Jackson. 1981. The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2: 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, Christina, Wilmar B. Schaufeli, and Michael P. Leiter. 2001. Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology 52: 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkelsen, Eva G., Åse M. Hansen, Roger Persson, Maj F. Byrgesen, and Annie Høgh. 2020. Individual consequences of being exposed to workplace bullying. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace. Developments in Theory, Research, and Practice, 3rd ed. Edited by Stale Einarsen, Helge Hoel, Dieter Zapf and Cary L. Cooper. Boca Raton: CRC Press, pp. 163–208. [Google Scholar]

- Minibas-Poussard, Jale, Christine Roland-Levy, and Haluk B. Bingol. 2025. Social representations of workplace aggression: A comparison between bullied and non-bullied bank workers. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research. In press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minibas-Poussard, Jale, Meltem Idig-Camuroglu, Tutku Seckin, and Haluk B. Bingol. 2022. Workplace Bullying and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms: A Double Mediation Model. Journal of Contemporary Economics and Administrative Sciences 12: 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, Elizabeth W. 2014. Employee voice and silence. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 1: 173–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabe-Nielsen, Kirsten, Matias Brødsgaard Grynderup, Paul Maurice Conway, Thomas Clausen, Jens Peter Bonde, Anne Helene Garde, Annie Hogh, Linda Kaerlev, Eszter Török, and Åse Marie Hansen. 2017. The role of psychological stress reactions in the longitudinal relation between workplace bullying and turnover. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 59: 665–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namie, Gary, and Pamela E. Lutgen-Sandvik. 2010. Active and passive accomplices: The communal character of workplace bullying. International Journal of Communication 4: 31. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, Joel H., and Loraleigh Keashly. 2004. Development of workplace aggression research questionnaire (WAR-Q): Preliminary data from workplace stress and aggression project. Paper presented at Theoretical Advancements in the Study of Antisocial Behavior and Work, Chicago, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, Kara, Karen Niven, and Guy Notelaers. 2022. Does bystander behavior make a difference? How passive and active bystanders in the group moderate the effects of bullying exposure. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 27: 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Kara, Karen Niven, and Helge Hoel. 2019. ‘I could help, but…’: A dynamic sensemaking model of workplace bullying bystanders. Human Relations 73: 1718–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, Morten Birkeland, and Stale Einarsen. 2012. Outcomes of exposure to workplace bullying: A meta-analytic review. Work & Stress 26: 309–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, Morten Birkeland, Guy Notelaers, and Ståle ValvatneEinarsen. 2020. Methodological issues in the measurement of workplace bullying. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace. Boca Raton: CRC Press, pp. 235–65. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, Morten Birkeland, Stale V. Einarsen, Sana Parveen, and Michael Rosander. 2024. Witnessing workplace bullying—A systematic review and meta-analysis of individual health and well-being outcomes. Aggression and Violent Behavior 75: 101908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omari, Maryam. 2007. Towards Dignity and Respect at Work: An Exploration of Bullying in the Public Sector. Ph.D. Thesis, Edith Cowan University, Joondalup, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Pauksztat, Birgit, Denise Salin, and Momoko Kitada. 2022. Bullying behavior and employee well-being: How do different forms of social support buffer against depression, anxiety and exhaustion? International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 95: 1633–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paull, Megan, Maryam Omari, and Peter Standen. 2012. When is a bystander not a bystander? A typology of the roles of bystanders in workplace bullying. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 50: 351–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paull, Megan, Maryam Omari, Premilla D’cruz, and Burcu Güneri Çangarli. 2020. Bystanders in workplace bullying: Working university students’ perspectives on action versus inaction. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 58: 313–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pines, Ayala M. 2005. The burnout measure, short version. International Journal of Stress Management 12: 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, Kristopher J., and Andrew Hayes. 2008. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods 40: 879–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purpora, Christina, Adam Cooper, Claire Sharifi, and Michelle Lieggi. 2019. Workplace bullying and risk of burnout in nurses: A systematic review protocol. JBI Evidence Synthesis 17: 2532–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, Neuza, Daniel Gomes, Gabriela P. Gomes, Atlat Ullah, Ana S. Dias Semedo, and Sharda Singh. 2024. Workplace bullying, burnout and turnover intentions among Portuguese employees. Journal of Organizational Analysis 32: 2339–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosander, Michael, and Morten Birkeland Nielsen. 2023. Witnessing bullying at work: Inactivity and the risk of becoming the next target. Psychology of Violence 13: 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosander, Michael, and Morten Birkeland Nielsen. 2024a. Is there a blast radius of workplace bullying? Ripple effects on witnesses and non-witnesses. Current Psychology 43: 12365–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosander, Michael, and Morten Birkeland Nielsen. 2024b. Workplace bullying in a group context: Are victim reports of working conditions representative for others at the workplace? Work & Stress 38: 115–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rosander, Michael, and Morten Birkeland Nielsen. 2025. Work ability and risk of turnover for bystanders to workplace bullying. International Journal of Stress Management 32: 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossiter, Louise, and Antigonos Sochos. 2018. Workplace bullying and burnout: The moderating effects of social support. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 27: 386–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salin, Denise. 2020. Human resources management and bullying. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace. Developments in Theory, Research, and Practice, 3rd ed. Edited by Stale Einarsen, Helge Hoel, Dieter Zapf and Cary L. Cooper. Boca Raton: CRC Press, pp. 521–35. [Google Scholar]

- Tehrani, Noreen. 2004. Bullying: A source of chronic post-traumatic stress? British Journal of Guidance & Counselling 32: 358–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirion, Anna S. C., Laetitia B. Mulder, Tim Kurz, Namkje Koudenburg, Annayah M. B. Prosser, Paul Bain, and Jan Willem Bolderdijk. 2024. The sound of silence: The importance of bystander support for confronters in the prevention of norm erosion. British Journal of Social Psychology 63: 909–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckey, Michelle R., and Annabelle M. Neall. 2014. Workplace bullying erodes job and personal resources: Between- and within-person perspectives. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 19: 413–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tümkaya, Songül, Sabahattin Çam, and İlknur Çavuşoğlu. 2009. Tükenmişlik ölçeği kisa versiyonu’nun Türkçe’ye uyarlama, geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalişmasi. Çukurova Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 18: 387–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, Atlat, and Neuza Ribeiro. 2024. Workplace bullying and job burnout: The moderating role of employee voice. International Journal of Manpower 45: 1720–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Brande, Whitney, Elfi Baillien, Hans De Witte, Tinne Vander Elst, and Lode Godderis. 2016. The role of work stressors, coping strategies, and coping resources in the process of workplace bullying: A systematic review and development of a comprehensive model. Aggression and Violent Behavior 29: 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkuil, Bart, Serpil Atasayi, and Marc L. Molendijk. 2015. Workplace bullying and mental health: A meta-analysis on cross-sectional and longitudinal data. PLoS ONE 10: e0135225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2019. Burn-Out an “Occupational Phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases (accessed on 24 June 2025).

| In the Last Six Months | A Few Times a Month | A Few Times a Week | Almost Every Day |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assignment of excessive tasks beyond one’s capacity or without sufficient time | 20.7% | 22.3% | 22.3% |

| Lack of recognition or praise one believes is deserved | 24.4% | 15.7 % | 29.8% |

| Assignment of tasks below one’s qualifications or unnecessarily simple work | 20% | 16.9% | 22.3% |

| Being the subject of gossip, slander, or rumors behind one’s back | 18.2% | 20.2% | 17.8% |

| Complete disregard for one’s contributions | 28.9% | 14.5% | 22.5% |

| Appropriation of one’s success or ideas by others | 16.7% | 19% | 15.3% |

| Intentional delays in matters important to oneself | 24% | 14.5% | 21.5% |

| Constant opposition to one’s decisions or opinions | 22.3% | 10.4% | 20.2% |

| Deliberate withholding of information necessary to perform one’s job | 24% | 14% | 15.3% |

| Intentional denial of help to cause difficulties | 20.7% | 14.9% | 14.2% |

| Relentless criticism of one’s work or constant fault-finding | 24% | 14% | 14.9% |

| Being blamed for mistakes made by others | 28% | 12.8% | 14.9% |

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Workplace bullying | 76.11 | 18.20 | |||

| 2. Burnout | 34.90 | 6.92 | 0.14 * | ||

| 3. Bystander silence | 15.95 | 5.27 | 0.24 ** | 0.21 ** | |

| 4. Perceived stress | 30.25 | 3.08 | 0.24 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.18 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Minibas-Poussard, J.; Seckin, T.; Bingöl, H.B. From Bystander Silence to Burnout: Serial Mediation Mechanisms in Workplace Bullying. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 540. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090540

Minibas-Poussard J, Seckin T, Bingöl HB. From Bystander Silence to Burnout: Serial Mediation Mechanisms in Workplace Bullying. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(9):540. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090540

Chicago/Turabian StyleMinibas-Poussard, Jale, Tutku Seckin, and Haluk Baran Bingöl. 2025. "From Bystander Silence to Burnout: Serial Mediation Mechanisms in Workplace Bullying" Social Sciences 14, no. 9: 540. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090540

APA StyleMinibas-Poussard, J., Seckin, T., & Bingöl, H. B. (2025). From Bystander Silence to Burnout: Serial Mediation Mechanisms in Workplace Bullying. Social Sciences, 14(9), 540. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090540