The Lived Experiences of Youth-Workers: Understanding Service-Delivery Practices Within Queensland Non-Government Residential Youth Care Organisations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

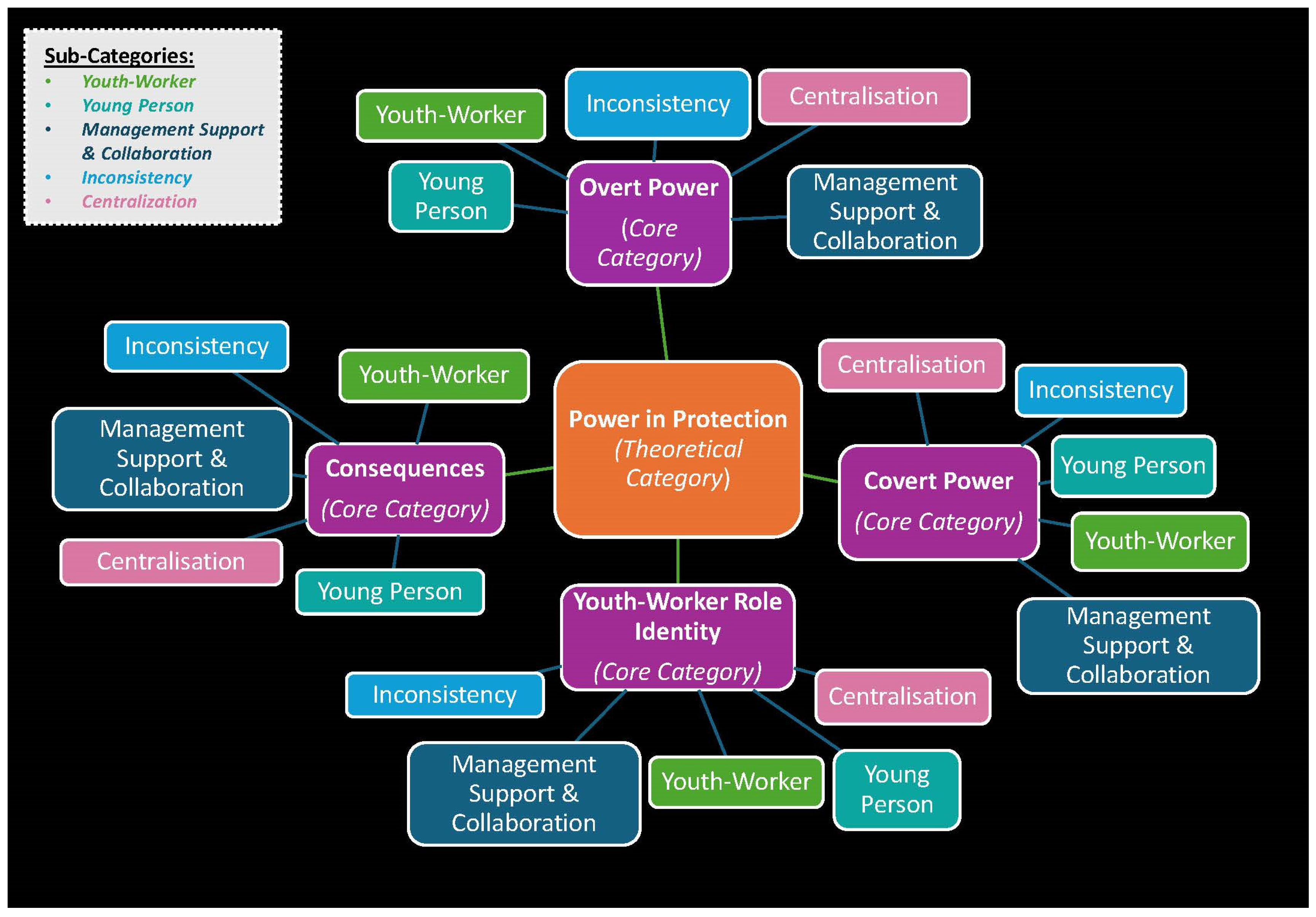

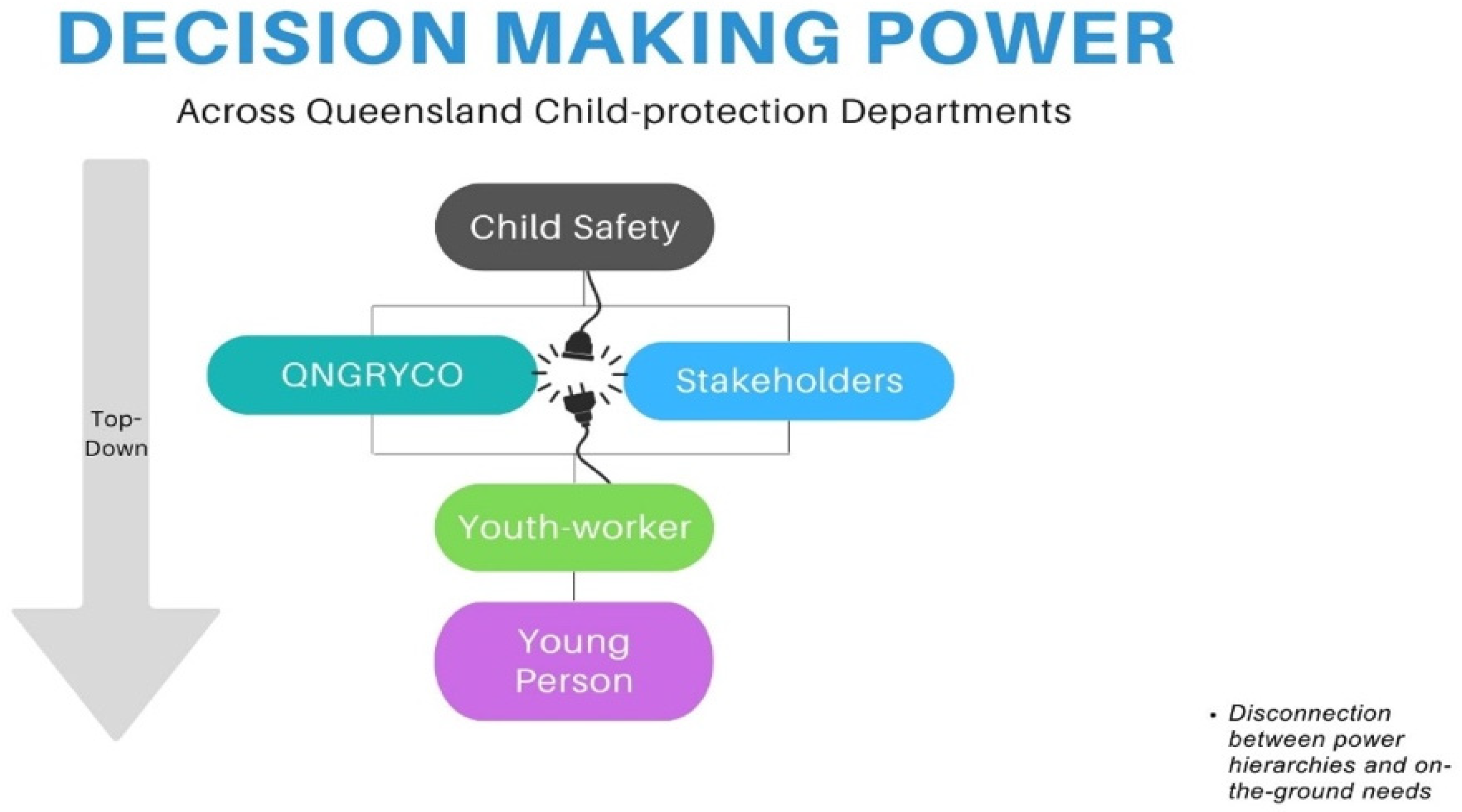

3.1. Power in Protection

3.2. Overt Power

“got to his 18th birthday and we were told oh yep, he’s got somewhere to go, … I got

together a glory box for him just so he’s got something in the new place, and just as

we’re about to go child safety ring and there like oh no that accommodation

fallen over, I kinda went like oh okay so where where do we go, and … they go oh we

don’t care where you take him but he can’t stay”

“then you have a child from straight out of community, right, and brought straight into a resi, you’ve gotta remember A) now there the different one in the community not you because everybody’s now white not black, in the first month, any of the community kids live together in the lounge room on one mattress, you know, because how can you work that rule when they have never ever been like that”

“Oh, no, that’s not good, just make sure you do your incident report and then go to sleep. I’m like yeah cool no worries I’m just chillin’ here with a concussion”.

“I get a phone call from a manager saying hey we’re just gonna not follow through with this part-time anymore just because you know on the weekend you called in sick because you were anxious”

3.3. Covert Power

“We had him join, he had won a sports award the year before, so we had him ready to go into footy, the whole bit, the morning he was getting out … of [juvenile detention centre] he rings me in distress, ‘child safety have, they’ve changed their mind’ and sent him back to Mount Isa. Three weeks in Mount Isa, stolen cars, back in back out of the big house”.

“Well, you believe in Attachment Theory. I’m certain we’ve all seen certain things

happen in the residential with children that decisions made above who don’t know the

child … yet they’ve formed attachments in placements and are starting to improve

behaviours and … suddenly, we’re moving them because it’s cheaper over there and

bugger the theory that our whole department is pro vised on”.

“The departments do, and unfortunately, the organisations are, sprout for the benefit of the child and Attachment Theory, yet none of them lives it or uses it”.

“I was leaving the organisation … no one was going to tell him because the worry was that he was going to react negatively so following instruction, which was not comfortable for me, but also what I had to do … well, he found out eventually … the week before I was due to not come back … he overheard it and then I was called in that night because he attempted to hang himself from the tree out the back. … he was just so upset and felt betrayed and very hurt… I was called in on shift that night because this was happening and they were like you need to he’s really only going to respond to you”

“abandonment is the, is the worst thing in the world, you know, and when … it’s like from your parents, like whether it was meant to be or whether it was just like taken, it’s something that you are never going to get over”.

“bang the kids were dragged out of the house screaming with workers … incredibly

distressed because we had no idea what was going on”.

“I would wake up in the morning with him pressed against the bedroom window crying saying please let me in, can I live with you, can I live with you, can I live with you?”

4. Recommendations and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alston, Margaret, and Wendy Bowles. 2018. Research for Social Workers: An Introduction to Methods, 4th ed. Oxford: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Association of Social Workers. 2023. AASW Practice Standards 2023. Available online: https://aasw-prod.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/AASW-Practice-Standards-FEB2023-1-1.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2024. Child Protection Australia 2022–23. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/child-protection/child-protection-australia-insights/data (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Ball, Rubini, Susan Baidawi, Susan, and Anthony FitzGerald. 2024. Approaches for supporting youth dually involved in child protection and youth justice systems: An international policy analysis. Journal of Criminology 4: 445–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollinger, Jenna, Stephanie Scott-Smith, and Phillip Mendes. 2017. How complex developmental trauma, residential out-of-home care and contact with the justice system intersect. Children Australia 42: 108–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory, Revised 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Children’s Court of Queensland. 2024. Annual Report 2023–24. Available online: https://www.courts.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/819771/cc-ar-2023-2024.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Commission for Children and Young People and Child Guardian. 2009. Annual Report 08–09. Available online: https://documents.parliament.qld.gov.au/tp/2009/5309T1334.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Department of Families, Seniors, Disability Services, and Child Safety. 2022. Child Safety Practice Manual. Available online: https://cspm.csyw.qld.gov.au/practice-kits/permanency-1/working-with-children/seeing-and-understanding/what-is-attachment (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Department of Families, Seniors, Disability Services, and Child Safety. 2023. Child Safety Practice Manual. Available online: https://cspm.csyw.qld.gov.au/practice-kits/transition-to-adulthood/working-with-young-people/responding-1/engagement-and-participation (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Department of Families, Seniors, Disability Services, and Child Safety. 2024. Our Community Partners. Available online: https://www.dcssds.qld.gov.au/about-us/our-department/partners/child-family/our-community-partners/placement-services (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Department of Families, Seniors, Disability Services, and Child Safety. 2025. What is Permanency Planning? Available online: https://cspm.csyw.qld.gov.au/practice-kits/permanency-1/overview-of-permanency/what-is-permanency-planning (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Fern, Edward F. 2001. Advanced Focus Group Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gatwiri, Kathomi, Lynne McPherson, Lynne Parmenter, Nadine Cameron, and Darkene Rotumah. 2021. Indigenous children and young people in residential care: A systematic scoping review. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse 22: 829–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grady, Melissa D, and Jamie Yoder. 2024. Attachment theory and sexual offending: Making the connection. Current Psychiatry Report 26: 134–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Rachael, Melissa Savaglio, Lauren Bruce, Ruby Tate, Kostas Hatzikiriakidis, Madelaine Smales, Anna Crawford-Parker, Sandra Marshall, Veronica Graham, and Helen Skouteris. 2023. Meeting the nutrition and physical activity needs of young people in residential out-of-home care. Journal of Social Work 23: 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallam, Karen T, Danielle Leigh, Cassandra Davis, Nathan Castle, Jenny Sharples, and James D. Collett. 2021. Self-care agency and self-carepractice in youth workers reduces burnout risk and improves compassion satisfaction. Drug and Alcohol Review 40: 847–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isobel, Sophie, Allyson Wilson, Katherine Gill, and Deborah Howe. 2020. What would a trauma-informed mental health service look like?: Perspectives of people who access services. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 30: 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanestrøm, Harald, Øystein Marianssønn Hernæs, Marianne Stallvik, Stian Lydersen, Norbert Skokauskas, and Jannike Kaasbøll. 2025. Do criminogenic needs matter in non-secure settings? Assessing change in dynamic risk factors during therapeutic residential care and the association with prediction and recidivism. Crime & Delinquency, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakouer, Jacynta, Sarah Wise, and Marie Connolly. 2018. We live and breathe through culture: Conceptualising cultural connection for Indigenous Australian children in out-of-home care. Australian Social Work 71: 265–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, Fernando, Melissa O’Donnell, Alison J. Gibberd, Kathleen Falster, Emily Banks, Jocelyn Jones, Robyn Williams, Francine Eades, Benjamin Harrap, Richard Chenhall, and et al. 2024. Aboriginal children placed in out-of-home care: Pathways through the child protection system. Australian Social Work 77: 471–85. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/0312407X.2024.2326505?needAccess=true (accessed on 29 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Lukes, Steven. 2005. Power: A Radical View, 2nd ed. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Malvaso, Catia Gaetana, and Paul Delfabbro. 2015. Offending behaviour among young people with complex needs in the Australian out-of-home care system. Journal of Child and Family Studies 24: 3561–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Karen, and Booran Mirraboopa. 2003. Ways of knowing, being and doing: A theoretical framework and methods for Indigenous and Indigenist research. Journal of Australian Studies 27: 203–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, Ben, Susan McVie, Carleen Thompson, and Anna Stewart. 2022. From childhood system contact to adult criminal conviction: Investigating intersectional inequalities using Queensland administrative data. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology 8: 440–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, Fiona Margaret. 2002. Inside Group Work: A Guide to Reflective Practice. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- McDowall, Joseph J. 2018. Out-of-Home Care in Australia: Children and Young People’s Views After Five Years of National Standards. Available online: https://create.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/CREATE-OOHC-In-Care-2018-Report.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Morais, Francisca, Catarina Pinheiro Mota, Paula Mena Matos, Beatriz Santos, Monica Costa, and Helena Carvalho. 2024. Facets of care in youth: Attachment, relationships with care workers and the residential care environment. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth 41: 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, Kate, Rebecca Dyas, Charles Kelly, David Young, and Helen Minnis. 2024. Reactive attachment disorder, disinhibited social engagement disorder, adverse childhood experiences, and mental health in an imprisoned young offender population. Psychiatry Research 332: 115–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Family Matters Leadership Group, SNAICC—National Voice for Our Children, Catherine Liddle, Paul Gray, and Tatiana Corrales. 2024. Family Matters Report 2024: Strong Communities, Strong Culture, Stronger Children. Available online: https://www.snaicc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/241119-Family-Matters-Report-2024.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Oates, Fiona. 2020. Barriers and solutions: Australian Indigenous practitioners on addressing disproportionate representation of Indigenous Australian children known to statutory child protection. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 16: 171–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei, Gerhon K, Kevin M Gorey, and Debra M Hernandez Jozefowicz. 2016. Delinquency and crime prevention: Overview of research comparing treatment foster care and group care. Child & Youth Care Forum 45: 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Payne, Malcom. 2020. Modern Social Work Theory, 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Queensland Child Protection Commission of Inquiry. 2013. Taking Responsibility: A Roadmap for Queensland Child Protection. Available online: https://cabinet.qld.gov.au/documents/2013/dec/response%20cpcoi/Attachments/report%202.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Queensland Family and Child Commission. 2018. Young People’s Perspectives of Residential Care, Including Police Call-Outs. Available online: https://www.qfcc.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-06/Young%20people%20s%20perspectives%20on%20residential%20care%2C%20including%20police%20call-outs.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Queensland Family and Child Commission. 2022. QFCC Oversight Framework 2023–2027. Available online: https://www.qfcc.qld.gov.au/sector/monitoring-and-reviewing-systems/oversight (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Queensland Family and Child Commission. 2023a. ‘I Was Raised by a Checklist’: QFCC Review of Residential Care. Available online: https://www.qfcc.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-10/I%20was%20raised%20by%20a%20checklist%20-%20QFCC%20Review%20of%20Residential%20Care.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Queensland Family and Child Commission. 2023b. Deaths of Children and Young People Queensland 2022–2023. Available online: https://www.qfcc.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-03/QFCC_Report_Child_Deaths_2022-23_Accessible2.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Queensland Family and Child Commission. 2024a. Crossover Cohort: Young People Under Youth Justice Supervision and Their Interaction with the Child Protection System. Available online: https://www.qfcc.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-11/Crossover%20Cohort%20-%20Data%20Insights.pdf#:~:text=For%20all%20young%20people%20who%20were%20under%20youth,between%201%20July%202013%20to%2030%20June%202023 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Queensland Family and Child Commission. 2024b. Too Little, Too Late: The Progress Made Against the Queensland Residential Care Roadmap. Available online: https://www.qfcc.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-12/Too%20little%20too%20late%20-%20The%20progress%20made%20against%20the%20Queensland%20Residential%20Care%20Roadmap.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Queensland Family and Child Commission. 2025. Buyer Beware: How Economic Forces Are Shaping Queensland’s Residential Care Market. Brisbane: Queensland Government. Available online: https://www.qfcc.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/2025-08/Paper-Buyer-Beware-How-economic-forces-are-shaping-Queenslands-residential-care-market.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Robbins, Stephen P, Timothy Judge, Bruce Millet, and Michael Jones. 2010. OB: The Essentials. Frenchs Forest: Pearson Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Commission into the Institutional Response to Sexual Abuse. 2017. Final Report: Historical Residential Institutions. Available online: https://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/final_report_-_volume_11_historical_residential_institutions.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Sellers, Deborah E., Elliot G. Smith, Charles V. Izzo, Lisa A. McCabe, and Michael A. Nunno. 2020. Child feelings of safety in residential care: The supporting role of aadult-child relationships. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth 37: 136–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, Michael. 2006. Social Work and Social Exclusion: The Idea of Practice. New York: Routledge. Available online: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/jcu/detail.action?docID=429846 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Staines, Jo. 2017. Looked after children and Youth Justice: A response to recent reviews. Safer Communities: A Journal of Practice, Opinion, Policy and Research 16: 102–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinkopf, Heine, Dag Nordanger, Brynjulf Stige, and Anne Marita Milde. 2022. How do staff in residential care transform Trauma-Informed principles into practice? A qualitative study from a Norwegian child welfare context. Nordic Social Work Research 125: 625–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Yvonne, Lex Colletta, and Anna E Bender. 2021. Client violence against youth care workers: Findings of an exploratory study of workforce issues in residential treatment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 36: 1983–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urquhart, Cathy. 2023. Grounded Theory for Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide, Revised 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Vamvakos, Christopher, and Emily Berger. 2024. Residential care worker perceptions on the implementation of trauma-informed practice. Children and Youth Services Review 159: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Tamara, Karen Healy, and Jemma Venables. 2023. Comparing apples with oranges? Practitioner perspectives on the inconsistencies between family law and child protection. Australian Journal of Family Law 36: 154–72. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, James K, Lisa Holmes, Jorge F. del Valle, and Sigrid James. 2022. “Revitalizing residential care for children and youth: Cross-national trends and challenges. In Australian Residential Care: Creating Opportunities for Hope and Healing. Edited by James K. Whittaker, Lisa Holmes, Jorge F. del Valle and Sigrid James. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wales, K.; Zuchowski, I.; Hamley, J. The Lived Experiences of Youth-Workers: Understanding Service-Delivery Practices Within Queensland Non-Government Residential Youth Care Organisations. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 534. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090534

Wales K, Zuchowski I, Hamley J. The Lived Experiences of Youth-Workers: Understanding Service-Delivery Practices Within Queensland Non-Government Residential Youth Care Organisations. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(9):534. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090534

Chicago/Turabian StyleWales, Kassandra, Ines Zuchowski, and Jemma Hamley. 2025. "The Lived Experiences of Youth-Workers: Understanding Service-Delivery Practices Within Queensland Non-Government Residential Youth Care Organisations" Social Sciences 14, no. 9: 534. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090534

APA StyleWales, K., Zuchowski, I., & Hamley, J. (2025). The Lived Experiences of Youth-Workers: Understanding Service-Delivery Practices Within Queensland Non-Government Residential Youth Care Organisations. Social Sciences, 14(9), 534. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090534