Suicide is the third leading cause of death for young people aged 15–29 years across the globe and is regarded as preventable with evidence-based interventions (

O’Neil et al. 2012;

WHO 2025). Over the past two decades, rates of death by suicide among young people on the island of Ireland have been above international averages, with certain groups of young people, especially those experiencing structural and social inequalities, showing higher rates than comparable age groups in other European countries (

Bertuccio et al. 2024;

NOSP 2021;

Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency 2025;

O’Farrell et al. 2016;

Samaritans 2025;

UNICEF 2025). While many factors are associated with contributing to suicide, this type of death is linked directly with mental health problems, making early intervention an important healthcare topic (

NOSP 2024;

WHO 2024). Mental health problems often emerge early in the lifespan (

Kessler et al. 2007;

Solmi et al. 2022) and can impact a young person’s quality of life, education, and employment, with well-documented effects that persist into adulthood (

Bilsen 2018;

Finkelhor et al. 2015;

Patel et al. 2007;

Pompili 2018;

WHO 2024). Early intervention depends on both access to healthcare and a decision to seek help, but young people are described as having low mental health help-seeking rates (

Doan et al. 2020;

Goodwin et al. 2016), often preferring to self-manage (

Lynch et al. 2025a;

Radez et al. 2021) or wait until distress is severe before initiating help-seeking (

Biddle et al. 2007).

Help-seeking as a behaviour involves three features: the task or problem, the recipient of help, and the helper (

Nadler 1987). It can be described as an important coping mechanism or problem-solving approach that people employ to assist them with a task (

Chan 2013;

Rickwood et al. 2005). In learning contexts, help-seeking refers to an instrumental behaviour (

Nelson-Le Gall and Glor-Scheib 1985) and is an essential component in how children acquire skills and solve abstract problems (

Martín-Arbós et al. 2021;

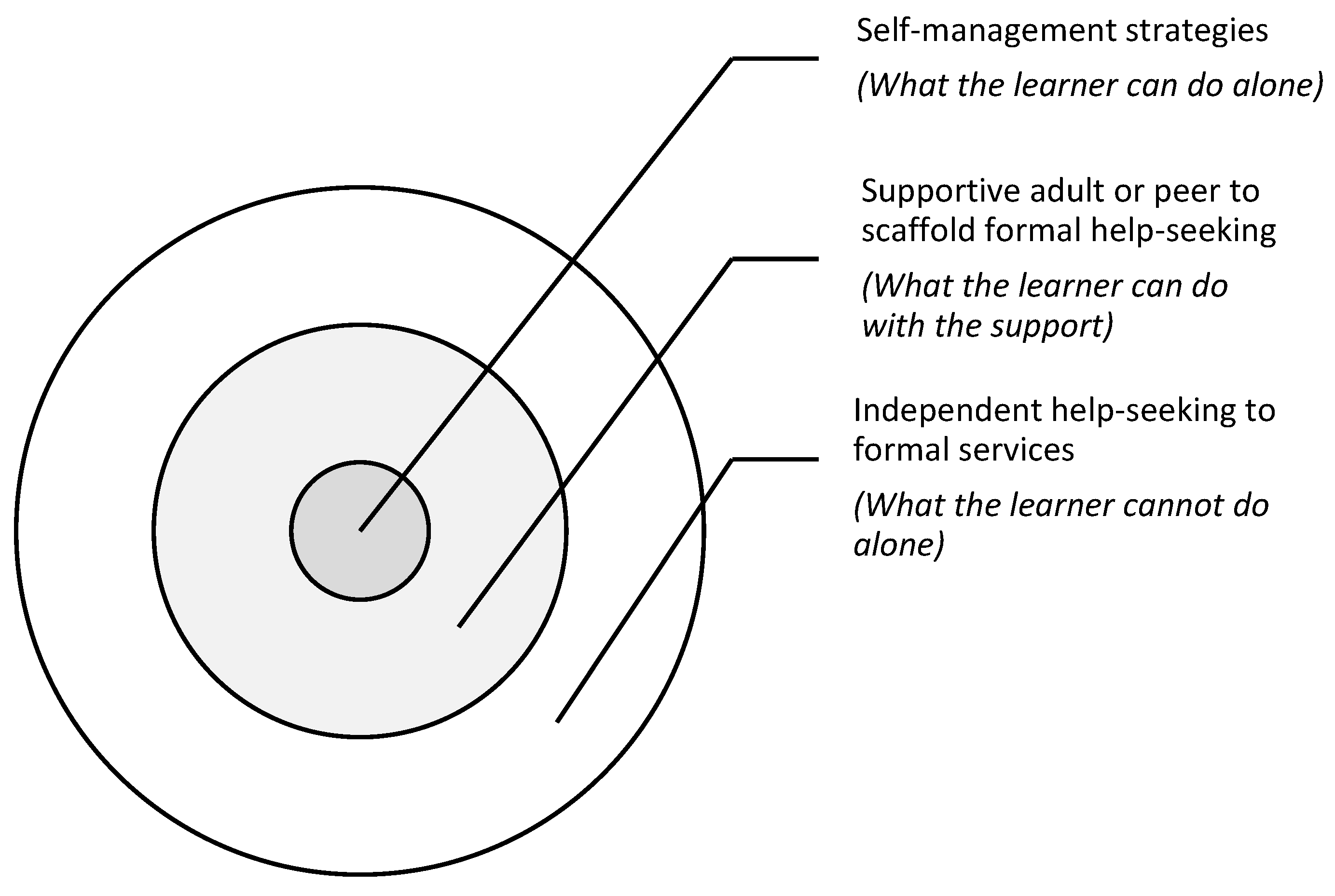

Mathews and Mitrović 2008). The help-seeking relationship in learning contexts can be understood through

Vygotsky’s (

1978) concept of the

Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which describes three zones: 1. the tasks a learner can do independently; 2. the tasks they cannot do; and 3. the tasks wherein a more knowledgeable other scaffolds the learning. Difficulties or pressure points that occur during learning are supported dialectically and iteratively through interactions with a knowledgeable other, until the learner can make sense of the challenge, with support lessening as ability increases (

Wood et al. 1976). In healthcare contexts, help-seeking involves identifying and labelling a problem, locating and seeking help, and disclosing distress to another person in exchange for support (

Cornally and McCarthy 2011). As this type of help-seeking involves planning and action, healthcare help-seeking models and frameworks are typically informed by the

Theory of Planned Behaviour (

Ajzen 1991), which posits that an individual’s attitude towards a behaviour, the subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control influence their intentions to seek help (

Chan 2013;

Breslin et al. 2021). Additionally, because healthcare providers shape access pathways (

Aday and Andersen 1974), healthcare help-seeking can require specific skills for accessing services (

Rickwood et al. 2005).

The literature base on mental health help-seeking and young people is sizable, spanning over 20 years of inquiry, yet a systematic review by

Aguirre Velasco et al. (

2025) found there to be no agreed-upon help-seeking term or model used in research on the topic. Despite this, the extant literature has extensively examined many barriers and facilitators impacting young people seeking help and has increased understanding on a range of personal, social, cultural, and service factors (

Doan et al. 2020;

Gulliver et al. 2010;

Goodwin et al. 2016;

Michelmore and Hindley 2012;

Nam et al. 2010;

Radez et al. 2021;

Rothì and Leavey 2006;

Rowe et al. 2014). Research on personal factors has reported on the central role of beliefs and attitudes towards services, professionals and help-seeking (

Chen et al. 2014;

Rothì and Leavey 2006), mental health literacy (

Pearson and Hyde 2021) and how young people conceptualise mental health problems (

Lynch et al. 2025a). Social factors that can impact young people’s help-seeking processes include the role of informal supports for facilitating or blocking help-seeking (

Breslin et al. 2021;

Lynch et al. 2023) and family and community resilience within ecosystems (

Ungar 2011), as well as stigma, cultural attitudes and expressions of distress (

Byrow et al. 2020;

Gulliver et al. 2010;

Goodwin et al. 2016;

Radez et al. 2024). Service factors that have been identified as impacting help-seeking during youth include financial and accessibility barriers (

Lynch et al. 2025b;

Radez et al. 2021), and the suitability of service design for young people (

McGorry et al. 2019;

Lynch et al. 2024;

Radez et al. 2021). However, there is limited research directly exploring the help-seeking processes of young people who have attended mental health services, including how they make decisions and search for help, and further research is needed to develop youth-specific help-seeking models and frameworks (

Aguirre Velasco et al. 2025). In addition, while much of the literature has focused on help-seeking barriers and facilitators, there has been less evaluative research on the impact of the help-seeking process itself—specifically how young people make meaning of these experiences, and how this meaning-making affects both their mental health and future help-seeking decisions (

Law et al. 2020;

Rayner et al. 2018). Qualitative inquiry into lived experiences can advance understanding of youth help-seeking processes, which in turn can inform theory development, improve the facilitation of access to mental health interventions, promote earlier intervention, and contribute to suicide prevention measures (

Bramesfeld et al. 2006;

NOSP 2024;

O’Neill et al. 2018;

WHO 2025).

1. Aim and Scope of This Study

The aim of this research was to explore how young people with a mental health problem decide to search and ask for professional help, and the impact of help-seeking experiences. This research had four objectives: (1) to explore how young people with mental health problems make a decision to seek professional help; (2) to examine how young people subsequently search and ask for help at a service; (3) to evaluate the impact of young people’s help-seeking experiences on their mental health and well-being; and (4) to identify help-seeking patterns that can support theory development on how young people seek help for their mental health problems. In this article, both terms “young people” or “youth” describe people aged approximately 10 to 25+ years in line with the developmental theories of adolescence and emerging adulthood (

Arnett 2023;

WHO 2024). The term “mental health problem” describes the spectrum of personal distress and mental conditions that can negatively affect a person or cause challenge to their well-being (

Lynch et al. 2025a). Finally, “help-seeking” refers to a process that a person engages in when they look for external support in lowering distress and managing their mental health problems (

Chan 2013;

Lynch et al. 2024).

2. Methods

2.1. Research Design

Researching youth mental health help-seeking processes required a design that was both systematic and flexible, to gain in-depth insight into this complex social phenomenon that is shaped by personal meaning-making, social relationships, and structural conditions. Constructivist Grounded Theory (CGT) (

Charmaz 2014) was employed as it provides systematic guidelines for qualitative inquiry and collection of rich data, and supports theory development through a grounded, process-oriented understanding of help-seeking that accounts for the interplay between individual, social, and systemic influences. This study adopts Charmaz’s constructivist approach, which combines the inductive, comparative, and emergent tradition of

Glaser and Strauss (

1967) with a constructivist epistemology (

Mills et al. 2006).

Charmaz (

2014) conceptualises experience not as a neutral record of events but as a process of meaning-making, constructed through personal interpretation, social context, and the interaction between researcher and participant. Through explorations of lived experiences, the researcher and the participant co-construct meaning and examine how young people interpret and respond to their own mental health needs, how these interpretations shape their help-seeking processes and how such experiences influence their well-being and future help-seeking decisions. This iterative process enabled an exploration of both the subjective experiences and the unfolding dynamic processes of help-seeking, supporting the study aim and objectives, and theory development.

2.2. Study Participants

Participants in this study included 18 young people aged between 16 and 25 years who had experiences of professional help-seeking for their mental health. This included those who had initiated help-seeking but did not engage with a service (i.e., did not attend, did not meet service criteria, or were put on waiting list), those who disengaged early from support, and those who engaged with longer-term support. Participants self-reported their demographic information, which is available in

Table 1, which is presented in a manner that safeguards participant anonymity.

The research findings were part of a larger study (N = 24) that collected qualitative data on youth experiences of seeking help for their mental health and included young people (n = 18) and mental health practitioners (n = 6). As this article focuses on young people’s experiences of making decisions to seek help for mental health and the personal impact of this decision, only data from youth participants (aged 16–25 years) were reported (N = 18).

2.3. Participant Selection

The selection criteria ensured a broad range of perspectives but given the nature of the topic, young people who were in acute psychological crisis or at the very beginning of their engagement with a mental health service were excluded (

Table 2).

This decision was made by the research team to avoid the risk of participant re-traumatisation and to ensure that enough time had passed to reflect with perspective on their help-seeking processes. The recruitment period remained open for eight months, allowing young people no longer in crisis or further along in their help-seeking process to participate. Through conversations with the researcher (LL), participants were able to discuss how they met the selection criteria, and all young people who volunteered to take part were supported to participate.

Formal mental health services were defined as providers and professionals with a specified role in delivery of mental healthcare such as counsellors, psychologists, psychiatrists, and mental health nurses and similarly,

semi-formal mental health services included providers and professionals who encounter or provide support with those who need mental health care as part of other duties, typically school guidance counsellors and youth workers (

Lynch et al. 2024;

Rickwood et al. 2005).

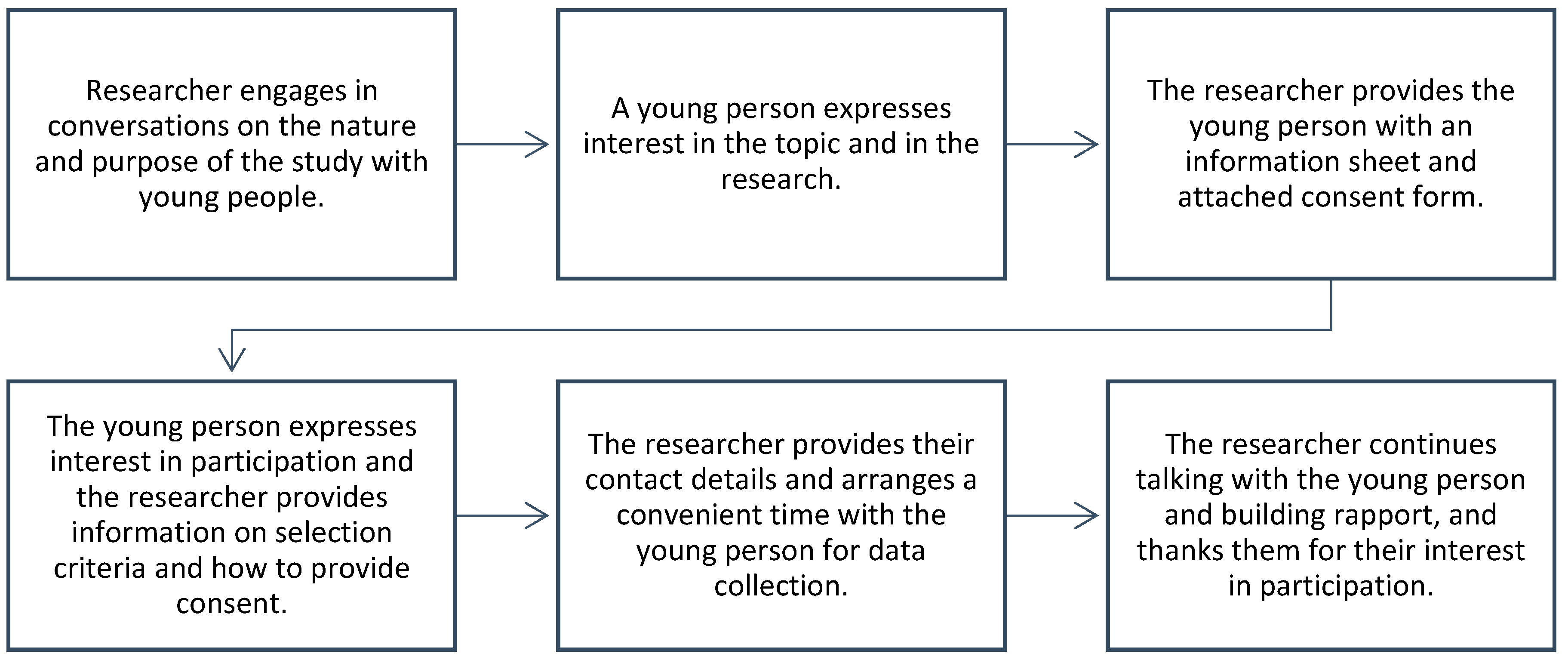

2.4. Participant Recruitment

This research utilised both

purposive sampling and

snowball sampling techniques to recruit participants through a local community service. Purposive sampling ensured successful recruitment of individuals with diverse experiences (

Bryman 2012) and the use of snowball sampling helped recruit participants through existing staff networks, which supported trust development and rapport building (

Barbour and Barbour 2003;

Naderifar et al. 2017). Participants were recruited through two methods. First, youth work practitioners shared participant information sheets with young people they believed might be interested in participating in mental health research, who then contacted the researcher directly for further information and a consent form. Secondly, with permission from service management, recruitment took place in the service drop-in space. This supported advertisement of the research and open discussion with service-users who expressed curiosity, which proved successful for recruitment (

n = 10) (

Figure 1).

Participants self-selected to an interview or focus group (

Lynch et al. 2018). Data collection also occurred at the same local community service, with fourteen participants volunteering to participate for interviews and six taking part in a focus group. Two young people withdrew before the focus group commenced and two focus group participants volunteered to do an interview (two participants took part in both a focus group and interview), resulting in eighteen participants in total taking part in this study, which included young people aged 16–19 (

n = 7) years and 20–25 years (

n = 11).

2.5. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ulster University Research Ethics Committee. No incentives were offered, and participation was voluntary with both verbal and written informed consent obtained in advance of collection. Participants were provided with an information sheet detailing the aims, methods, procedures, the type of data collected, expected duration, how data would be used for publication, limits of confidentiality (focus groups and in the event of disclosures), planned outcomes, prospective research benefits and the contact details of the researcher (

British Psychological Society 2014). Two participants aged 16–18 years of age obtained parental consent to participate and were offered the option to have a chosen adult present during data collection. The researcher conducting data collection was trained in child safeguarding, and a distress protocol was devised in the case of participant distress or disclosure of child abuse, neglect, suicidal plans or criminal activities that are legally obliged to be reported (

Ulster University 2018), however there were no safeguarding disclosures. In addition, all research was conducted in line with The British Psychological Society’s

Ethical Principles for Conducting Research with Human Participants (2014), the General Data Protection Regulation (2018), Data Protection Act (2018), and Freedom of Information Act (2000). Pseudonyms were assigned to all participants, and all personal and identifiable information were removed. Additionally, certain potentially identifiable content within in-text quotations were modified, omitted, or anonymised further by the removal of a pseudonym, where necessary to protect participant anonymity.

2.6. Data Collection

All aspects of data collection were completed in partnership with participants (

Richards 2020). Data collection comprised one-to-one interviews, for private and confidential conversation, and a focus group, which was an interactive and developmentally appropriate method for supporting discussion (

Gibson 2007). The limits of confidentiality within focus groups were discussed before proceeding. Interviews offered participants the opportunity to discuss their experiences and individual perspectives, outside of the group context, which increased comfort to explore deeply the subjective reality of help-seeking for a mental health problem (

Bryman 2012). This blend of qualitative methods, sometimes referred to as methodological triangulation, supported insight from the subjective and the group realities and has been reported as contributing to both data completeness and the trustworthiness of research (

Creswell and Miller 2000;

Golafshani 2003;

Lambert and Loiselle 2007;

Vandermause 2007). Alongside enhanced analysis, the self-selection approach increased participation, comfort, and convenience for participants (

Morse et al. 2002;

Lambert and Loiselle 2007;

Lambert and Loiselle 2008). Data collection took place between May 2018 and December 2019 in a comfortable room within a community-based building where participants attended at a convenient time. The room was designed for privacy and for safeguarding, making it ideal for collecting data confidentially with young people. Participants were greeted and offered refreshments, and consent was affirmed before data collection began. These sessions were audio recorded and lasted between 20 min and 1 h 10 min and participants were appropriately debriefed before they left the premises. A semi-structured interview and focus group guide were used to explore young people’s experiences of mental health help-seeking and consistent with the CGT approach, each interview or focus group was treated as a unique dialogue in which participants and researcher collaboratively explored experiences, perspectives, and beliefs, generating new understandings that informed subsequent data collection (

Mills et al. 2006). Participants were asked about their decisions and searches for help, and how these help-seeking experiences impacted their mental health and well-being. The decision to stop data collection was informed by saturation, which meant that the sampling technique was not providing any new properties (

Charmaz 2014). All participants received verbal and written debriefing.

2.7. Data Analysis

The researcher (LL) was engaged in analysis at all stages of the study (

Charmaz 2014) and CGT techniques including data familiarisation, memo writing, and the constant comparative method were used iteratively throughout the research process. Following transcription in sequential order, the data were systematically coded and analysed using NVivo 12. Initial coding used a combination of

word-by-word,

line-by-line, and

incident with incident techniques to organise rich data (

Charmaz 2014).

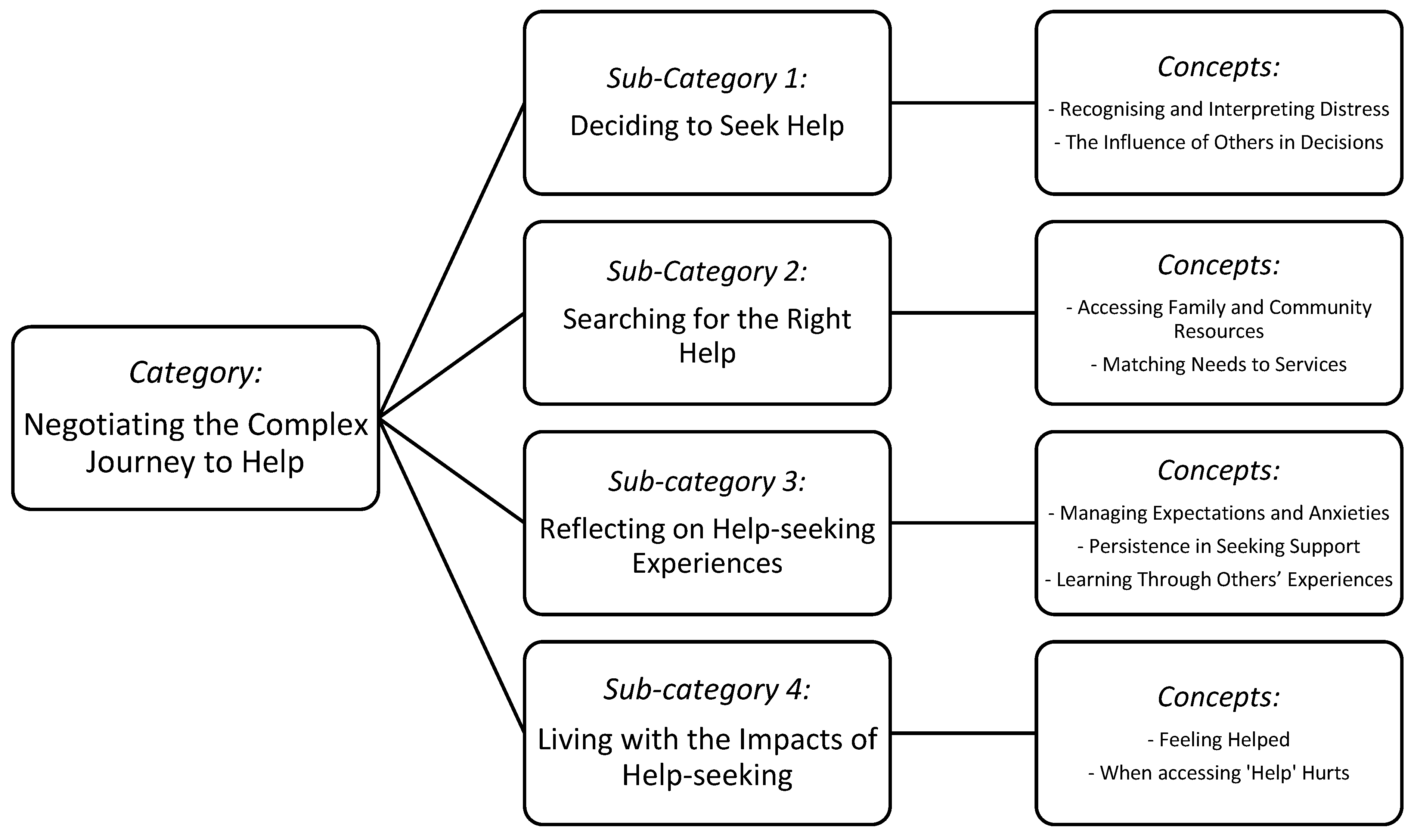

Focused coding was the process of organising these initial codes into categories and sub-categories that formed the overall theoretical concept of “Negotiating the complex journey to help”. Interview and focus group data sets were first analysed separately using the same process and later integrated, resulting in a complementary analysis (

Lambert and Loiselle 2008).

2.8. Integrity in Research

2.9. Positionality

This positionality statement reflects my perspective as the primary researcher (LL) who designed and conducted the research, and analysed the data, with my co-authors providing supervisory guidance, critical feedback, and review of analysis and manuscripts. I come from a multidisciplinary academic background including history, psychology, sociology, and counselling, and worked professionally as a community youth work practitioner. In that role, I provided support to young people experiencing mental health challenges and crises, and collaborated with a network of professionals across schools, youth centres and formal mental health services to facilitate access to support. I witnessed firsthand the complexities of help-seeking for young people and their families, and this motivated my interest in this area of study. I have been shaped and impacted by these stories and hold the belief that early intervention is critical, but that young people can be marginalised in health systems when they are not designed for them. I acknowledge my position of privilege, through my former role of being a gatekeeper to services, and as an adult who has outgrown the marginalisation that young people can experience. I use this position to approach research as a partner, underpinned by a commitment to centre youth voices in research and practice, to critically examine how we value young people, and to translate their experiences into knowledge that can inform more responsive and equitable mental healthcare.

3. Findings

This section presents findings on young people’s help-seeking processes, how they decided to seek help for their mental health, how they searched for support and services, and the impact that help-seeking had on them. These experiences are encapsulated under the central category “Negotiating the complex journey to help”, and findings are presented across four sub-categories:

1.

Deciding to Seek Help;

2. Searching for the Right Help;

3. Reflecting on Help-seeking Experiences; and

4. Living with the Impacts of Help-seeking (

Figure 2).

3.1. Sub-Category 1: Deciding to Seek Help

When reflecting on help-seeking decisions, participants described how they first identified their need for help with their mental health problems and the role that family, friends and teachers played in supporting self-awareness and arriving at decisions.

3.1.1. Recognising and Interpreting Distress

Deciding to seek help was described by participants as complex and involving many factors. All participants discussed how experiencing high distress alongside increasingly ineffective self-management strategies initially triggered thoughts of help-seeking: “I thought I can beat this on my own and it probably took me a couple of years just to realise that… I needed to reach out” (Joseph). Young people struggled with interpreting whether their distress was severe enough to seek help for: “Because I feel like people have worse problems than I do” (Richard), with some participants describing suicidal feelings as the first indicating sign that they should consider seeking help: “You have the choice of whether you’re going to get help or attempt suicide” (Rachel). Decisions were centrally informed by self-awareness of distress and the ability to communicate: “I couldn’t understand myself, so I didn’t know how I was meant to tell someone how I was feeling” (Laura). For many participants, it was only when their capacity to self-manage was exceeded that they could meaningfully consider seeking help: “I think going in at a low moment, kind of took down all the barriers that I may have put up” (Liam).

3.1.2. The Influence of Others in Decisions

Decisions to seek help could be recommended by others when externalising behaviours, such as aggression, were negatively impacting their relationships: “Things were going really down-hill so I had to speak to somebody … Mum essentially persuaded and persuaded until I finally gave in” (Richard). Sometimes a young person was approached by an adult outside of their family who noticed a change in their behaviour: “She [teacher] noticed my attendance and so she called me up for a wee chat in her room” (Josie, FG). Some participants described the experience of disclosing distress to a caregiver, GP or teacher during their adolescence and how a subsequent professional help-seeking decision was made on their behalf when that adult contacted services, without discussion or their consent: “I’ve been very mad ever since” (Niamh, FG). After turning eighteen, participants described an increased ability to make help-seeking decisions, in part because they no longer needed parental consent: “the ball is a bit at least, in your court, when you are older and more emotionally mature, it definitely helps with that” (Liam). Those who had delayed help-seeking during adolescence to avoid the involvement of caregivers described naturally reaching a point during emerging adulthood when the time to seek professional help felt right: “Then when I was 21, I was like okay it’s time to talk to someone” (Laura).

Once a professional help-seeking decision was made (or made for them), young people and their families considered their next steps in finding support.

3.2. Sub-Category 2: Searching for the Right Help

Young people spoke about the steps they took to find support. Some attempted to locate services independently, but more typically, young people turned to trusted others who had knowledge or skills to help them locate and access the right type of support they needed.

3.2.1. Accessing Family and Community Resources

After deciding to seek help, participants in this study described uncertainty about how or where to find a service, particularly during their adolescence. Family and other adults played a central role in leading the search, with some young people directly asking a caregiver or trusted adult to find professional support for them: “I just said to my mum one day, ‘I’m not feeling the best, could I chat to somebody?’” (Robert). Others asked for help indirectly, by changing their behaviour to signal their need for help to a receptive other: “He [guidance counsellor] knew where I was coming from. I thought I’ll be able to wake him up like, open his eyes to—I want to talk to you [with emphasis]” (Thomas). Trust was described as a pathway to help, as adolescents searching for help in schools or youth services described turning to people with whom they had an established rapport. The opportunity to observe potential helpers in youth environments over an extended period enabled young people to build trust and ask for support when they felt ready: “… like scouting him out… looking at his movements getting to know him a little bit…” (Andrew).

Friends and family were also reported as not always being able to offer support or provide resources with help-seeking: “nobody knew what mental health was about, so how are they going to tell me to go talk to somebody?” (Thomas). Some participants also described trying to manage different family and friends’ reactions to help-seeking, when their search could be supported by one person and unsupported by another: “I remember when I got my first appointment letter, [she] didn’t want me to go” (Rachel).

3.2.2. Matching Needs to Services

Locating a suitable mental health service could be challenging due to long waiting lists or a lack of youth-specific services locally. A few participants described having to travel long distances with parents to access youth counselling while others reported that they were able to access support in their school: “…I told her I need to talk to someone, so she sent me to the guidance counsellor” (James). For young people seeking help independently, having the confidence to approach a service and communicate needs, even in emerging adulthood, could be difficult: “I’d always be… like, ‘I’m going in tomorrow’ for the entire month and I just could not do it” (Laura). One participant described searching for the right help for many years, as their distress involved sexual abuse in childhood, as they were afraid of the consequences of help-seeking: “I was keeping a lot of secrets for other people, and I got very scared… I just didn’t want anybody to be upset”.

For young people with experiences of marginalisation, finding help involved identifying someone in their community networks that they could trust, a process that could take months or even years: “I think a part of why it took me so long to talk to someone was because I didn’t trust anybody [with emphasis]” (Thomas). Young people who identified as LGBTI+ often had to disclose their sexuality or gender identity in exchange for mental health support and described searching for signs of acceptance before approaching a helper. Áine noted that LGBTI+ young people often needed support due to marginalisation: “not because you’re more likely to have mental health problems, but because of the way you’re treated and bullied… you’re more likely to end up with mental health problems”. One young person described how help-seeking for his mental health meant disclosing that he was transgender and wanted to transition, a step that entailed the potential risk of further rejection, stigma or distress: “basically my problem was being forced into the role that didn’t fit me … I had no idea about how it would go when I told them everything.”

Many participants with family support sought help with a family doctor, who referred them on to public healthcare services. Others accessed free community services or private counsellors when financial support was available, and some turned to youth workers and school pastoral care support. While many participants had found the right help at the time of participation in this study, some stated that they were still searching.

3.3. Sub-Category 3: Reflecting on Help-Seeking Experiences

Participants reflected on their overall experience of the help-seeking process, including the expectations and thoughts they held during decisions and searches for help, how they continued to seek help after unsuccessful attempts, and how vicarious learning shaped their processes.

3.3.1. Managing Expectations and Anxieties

Young people discussed how their expectations of help-seeking were influenced by previous experiences of informal help-seeking to friends and family, and by exposure to mental health information and stereotypes in the media: “… a Freudian scene where you had to lie down on a couch! [laughs]” (Liam). Others anticipated a clinical approach, expecting someone to assess, diagnose, and “fix” their problems: “I just wanted her to solve my anxiety” (Claire). All participants expected to be helped, hoping for improved well-being and reduced distress: “I suppose there was real hope there that it would help in some way” (Joseph). Laura described the prospect of help as exciting: “I remember being in there and being like a bit excited… I’m going to counselling and I’m going to be able to talk to somebody and sort out my shit!”.

Fear and anxiety about meeting professionals, assessment processes and potential diagnosis were common during decision and search stages. Disclosing personal distress and painful memories to others was described as challenging and, at times, taboo: “I think it’s much easier for me to talk about it now because I’ve talked about it more times before … but imagine having to bring stuff up that was almost unspoken of since you were a kid” (Thomas). While anticipatory anxiety was common when initially asking for help or meeting people working in a service, some participants described experiencing it at every session, accompanied by physical reactions such as shaking with fear or freezing: “I would just freeze and go very mute, and I couldn’t get the words out, no matter what I tried” (Laura). Rachel described how she would: “… get sick [vomiting] before I would meet her because I was very nervous”. Cathy reflected on how the process of engaging in a supportive relationship was difficult during adolescence: “…because of your experiences coming into your teenage years… coming out [about mental health difficulties] to an adult is a lot harder because you don’t want to be shamed by an adult…”. Some young people needed longer periods to feel safe enough to disclose to their helper the cause of their distress: “so I’d always be in my head, ‘I want to talk about this today’, but I never would” (Laura). Cathy described how she had to make new meaning about asking for help: “…it’s just a process you go through, and you have to learn that it’s okay to chat about it”, noting that even with a supportive helper in emerging adulthood, participating in therapy remained an ongoing challenging process of learning, trust-building and self-exploration.

3.3.2. Persistence in Seeking Support

Young people discussed how unhelpful or unsuccessful experiences could temporarily deter them from help-seeking, but with time or reoccurring distress, they sought help again using another approach. Participants described unsuccessful experiences with the help-seeking process, including being referred to the wrong service, lost referrals or no follow up to referral with an appointment, overreliance on psychopharmaceutical prescriptions by GPs without access to talking therapies, limited time for rapport building, therapeutic approaches that did not match their age-related needs, and practitioners who could not relate to them or who responded inappropriately, such as shaming, judging, or discharging them without referral to another service. After multiple help-seeking episodes, some participants described feeling defeated and losing motivation: “What happened to me then was that I had a little bit of a mid-teen crisis, where I was like I don’t want to get better” (Claire). Two participants described attempting suicide after multiple failed attempts to get help: “I knew that if I stopped taking my medication chances were, it would kill me”. Áine described an unexpected positive experience after negative experiences with help-seeking: “By the time I was seeing the youth worker, I didn’t really have [pauses] good expectations, so it massively exceeded them [laughs]”. By emerging adulthood, Joseph explained that through multiple unsuccessful help-seeking attempts, he had learned how to find the right help for him: “…somebody who has got the knowledge and the tools, and they’ve got the professionalism and everything else, that they’re going to help you”.

3.3.3. Learning Through Others’ Experiences

Participants spoke about the value they placed on hearing about others’ help-seeking experiences, which offered them the opportunity to shape expectations: “I saw my friend going through the same sort of stuff and then I saw her get better” (Laura). Young people also described hearing others’ accounts of help-seeking that had unhelpful or harmful consequences, including unsuitable or frightening in-patient experiences, such as children being placed in adult wards, involuntary participation in treatment, and lengthy service waiting lists:

… he had to wait so long that while he was waiting… he tried to kill himself and then the next day he was put on an emergency list, and he still had to wait half a year for it.

(James)

Joseph stated how hearing these types of stories undermined motivation to seek help, particularly to public healthcare services: “…if this is the way the services are? What is the point in bothering [help-seeking]?”. One participant discussed their experience of living with anger and trauma after a close friend died by suicide after a final help-seeking episode:

He was failed by the services… actually attempted suicide a couple of times and went up to the services to become an inpatient and said ‘listen if you do not bring me in now, I will kill myself’, he stated that, they said to him he was not sick enough to go in and so he killed himself the next day.

This participant described the impact that a friend’s experience can have on a person’s decision to seek help:

… you can’t believe a man that young is dead and buried, he had so much to live for, just married … I know there is a lack of resources there [public healthcare services] but how any human being questioning him—them people who turned him away, like what are you doing in your job that somebody is dead? That you knew were suicidal and you turned away? How can you do that as a human being? It’s beyond me … It’s grim … I just hope young men don’t hear the stories because you need hope and if a young man heard these stories … they’re not going to go for help.

This participant stated that discussing this was difficult, but said it was “… the reason I came here today”. They were motivated to participate in this research to tell their friend’s help-seeking story and his death by suicide, because he could not.

All participants described help-seeking as complicated, relationship-centered, and multi-episodic, often involving gaps that ranged from months to years. After multiple experiences of help-seeking, participants reflected on the more challenging aspects of the process and learned how to access the right type of support for them. Findings around unsuccessful attempts serve as an important reminder that many young people’s voices, and their experiences of seeking help from services, will never be heard.

3.4. Sub-Category 4: Living with the Impacts of Help-Seeking

In this final sub-category, young people described the lasting impacts of help-seeking on their lives and well-being, ranging from experiencing personal growth and feeling supported to compounded distress and deteriorating mental health.

3.4.1. Feeling Helped

When young people were asked how help-seeking had impacted them, many described improved well-being and increased feelings of connectedness from finding someone to offload difficult feelings to: “It’s not like my problems were solved, but at least… I have someone to talk to” (James). Experiencing genuine care from a helper had a positive and lasting impact on young people with low social support: “… there’s no words to put down how much that woman helped me” (Rachel). Participants reported positive impacts including increased self-worth, repaired self-image, greater confidence in help-seeking, enhanced self-efficacy from learning new self-management skills, improved self-awareness to “understand triggers”, and feelings of validation and reclaimed personal power: “I completely changed, it stopped me having panic attacks…I just did not care—like fuck it, I’m not going to cry over it anymore” (Laura).

Positive and non-stigmatising experiences supported new understandings of help-seeking and mental health: “I don’t think anybody should be afraid about speaking about mental health” (Andrew). Additionally, experiencing a trusting and supportive rapport provided participants with modelling that helped them repair existing relationships or build trust in new ones: “…that only comes from the fear going away… I trust people way, way easier now and I think that was part of it” (Thomas). Supportive relationships could leave participants feeling grateful or fortunate to have met their helper, particularly for those who felt lost in referral systems or had experienced multiple unsuccessful help-seeking episodes:

I was extremely lucky, I think… I don’t know how my experience would have been if I had someone completely different … the people providing help are often under others who control terms and conditions of mental health treatment… the people who help the most have the least power …

(Rachel)

Positive impacts were described by participants as an increased quality of life, improved relationships, and confidence in asking for help in the future.

3.4.2. When Accessing “Help” Hurts

Unhelpful mental health experiences had both short- and long-term impacts. After long waits for help, participants reported feeling disappointed, angry, and confused by inappropriate or inadequate care: “…and I was just thinking what am I doing here?” (Laura). Experiences of long waiting lists or no follow-up from a referral resulted in young people feeling devalued and uncared for: “How can it make you feel? Like shit. Like they don’t give a fuck. Sorry about the language” (Joseph). Participants also described how experiences of receiving referrals to services only to find that they did not meet service criteria or instances of abrupt endings due to service timeframes, triggered existing feelings of rejection or abandonment: “… just felt like she was cutting me off as if I was nobody” (Erin).

Many young people described experiences of feeling pathologized and stigmatised at services, particularly during assessments: “… this person had a clipboard and was ticking boxes and that just made me feel worse…” (Cathy). Rachel reported feeling scrutinised and mistrusted by public healthcare providers during follow-up appointments: “it’s like they are so sceptical of everything that comes out of your mouth, and they are so observant of how you act and eye contact and everything… what you say, if you stutter, if you’re shaking, everything”. Áine described how sometimes professionals responded during appointments without empathy or care for her distress, which deepened feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness: “why should I care if they don’t care?… it makes no odds if I do commit suicide”. Niamh discussed feeling patronised at a community support programme: “we had so many rules and things we had to follow….and if you’re a bit late you would get an eating [verbal punishment]”. Some participants described times when they felt blamed for not ‘getting better’ within service timeframes, punished for missed appointments by being discharged or referred onwards, or judged for being unable to follow a treatment plan: “Some weeks I wouldn’t want to talk and the mental health service, they would take that badly, they’d be kind of, ‘you’re not helping yourself’” (Áine).

Erin reported that poor rapport with her helper left her feeling “alienated at times” and how feelings of defectiveness were exacerbated when they used a CBT approach: “…they are the person that is trained in this, have the experience and all the knowledge … if it’s not helping me at all, then I feel like the problem is with me”. A care-experienced participant described feeling shame and embarrassment for having formed attachments and positive rapports with her helpers, which were severed when she was transferred to adult services upon turning eighteen: “I know I shouldn’t have become attached to them and become dependent on that service”. Joseph described feeling judged by his counsellor, who expressed her religious views about his life choices: “… and for her to tell me who I should, who I’m meant to be?”.

Clinical approaches were repeatedly described as causing feelings of objectification or dehumanisation: “Like you’re just invisible and [pauses] it’s also as if you’re just a number to them” (Áine). In particular, a couple of participants discussed feelings of violation that their mental health history was passed around in a file: “It was almost like I was going to this lady who knew everything about me, and I hadn’t even said a word” (Rachel). Many participants reported how experiences within an overcrowded public healthcare system left them feeling devalued: “…just trying to get as many people in and out as possible, diagnose them and push them on…” (Cathy). Consecutive unhelpful or harmful experiences with the public healthcare system had resulted in high distrust: “I think what they want to do, if they do get you in there, is put drugs in you and let you sit and look at the walls” (Joseph). One participant, following experiences with a friend’s death by suicide, became involved in mental health activism on social media, sharing resources and discussing mental health openly in a grassroots effort to challenge stigma and taboo: “I wouldn’t have been able to do it if not for what happened to my friend giving me the courage to just speak up, fuck that, this isn’t the way we need to be”.

When reflecting back on the impact of help-seeking, some participants reported regret at asking for help: “…I shouldn’t have told them anything” (Áine). Rachel described how her self-image was damaged from psychopharmaceutical treatment: “…what it felt like? Like there is something wrong with me and I need this to feel better…I was on Prozac… and it was like she was feeding [when administrating drug] a sick person”. Over time, repeated lack of access to adequate support exacerbated distress: “… because I wasn’t given the help that I needed at 8, by the time I got to 15, I had got ten times worse and by 16, I had given up on the mental health services” (Áine). Some described how their experiences at services heightened feelings of defectiveness: “Maybe I can’t be helped” (Erin), and fostered hopelessness that help-seeking could improve their mental health: “… what is the point of me not doing it [suicide]? because it’s not as if I’m going to get help” (Áine).

Overall, participants concluded that their help-seeking experiences had a significant impact on them, and the nature of that impact was dependent on whether their needs were met, the approach of the helper and the quality of support provided.

4. Discussion

This study investigated how young people navigated the process of seeking mental health support with services. To further knowledge on the topic and examine how help-seeking theory applies to younger people, it was essential to explore how and when a help-seeking decision was made, how they searched for professional help, and whether distinct patterns could be identified from their experiences. To consolidate understanding, exploring the impact that the help-seeking process had on their lives and well-being was key.

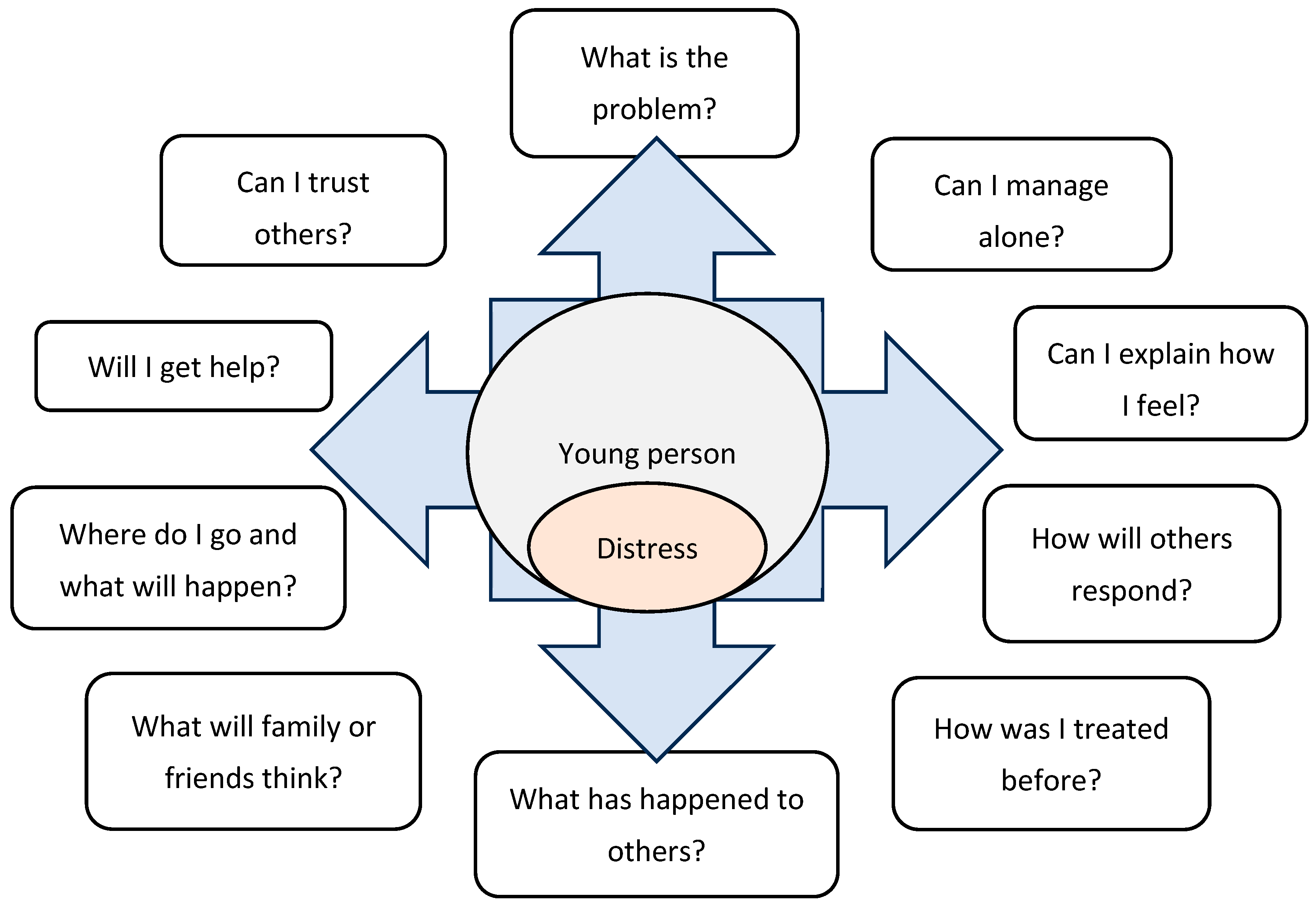

4.1. Help-Seeking Decisions and Searches in Youth

When deciding to seek professional help for a mental health problem, young people described this process as initiated by an internal barometer, whereby distress intensity triggered the need for action. For those experiencing ongoing elevated distress, suicidal feelings were often the first clear indicator that they needed external support. Help-seeking decisions were found to be fluid, and young people continuously evaluated the sources of help available to them, considering the availability and perceived effectiveness of help, self-management capacity, and protection from stigma (

Chan 2013;

Cornally and McCarthy 2011). Analysis of participant narratives identified the inter- and intrapersonal factors involved when deciding whether to begin, continue, or end a help-seeking episode, which were synthesised and are visually represented in

Figure 3.

Participants’ descriptions of help-seeking decisions were also analysed in relation to findings by

Cornally and McCarthy (

2011) and

Chan (

2013), which were informed by the Theory of Planned Behaviour (

Ajzen 1991), for alignment and divergence. Help-seeking decisions during youth involved having to recognise and define distress, assess self-management strategies, identify and acknowledge limitations, and reflect on attitudes towards help-seeking and how others would respond to this behaviour (

Ajzen 1991;

Chan 2013;

Cornally and McCarthy 2011). This research found that young people at any age were not fully equipped to make informed decisions for independent help-seeking, as engaging in the planned actions necessary for professional help-seeking required self-knowledge, the ability to reflect, analyse, and communicate difficult experiences. Development of these skills can be influenced by developmental capacity (

Best and Ban 2021), mental health conceptualisations (

Lynch et al. 2025a) and mental health literacy (

Pearson and Hyde 2021). In addition, as young people often lack the autonomy that adults have to make healthcare decisions, help-seeking decisions and actions were further constrained by this limited autonomy and service barriers, particularly restricted access and a lack of information (

Aday and Andersen 1974;

Lynch et al. 2025b;

Quinn et al. 2009;

Wilson and Deane 2012). Consequently, key adults were found in this research to be central in supporting young people to make decisions and choices in healthcare at all ages. During earlier adolescence (10–14 years), help-seeking decisions were more likely to be co-decided or initiated by others who noticed distress and encouraged or facilitated professional help-seeking (

Lynch et al. 2023). By later adolescence (15–19 years) and emerging adulthood (20–25 years), decisions tended to become increasingly independent with age and increasing capability.

Limited autonomy and the requirement for caregiver consent can explain why some young people delayed professional help-seeking until after turning eighteen (

Draucker 2005;

Wahlin and Deane 2012). This reflected a need for privacy and control over problems, especially when a young person expected or feared unsupportive responses or negative consequences from caregivers (

Coleman-Fountain et al. 2020;

Draucker 2005;

Freedenthal and Stiffman 2007;

Pearson and Hyde 2021;

Thai et al. 2020). Findings from this research suggest that this self-protective strategy can be beneficial, as some young people experienced further losses to autonomy and privacy when disclosing distress to an adult who then made the decision to seek professional help on their behalf, without consultation or explanation of the process. Additionally, exhausting self-management strategies before seeking help was important for a young person’s self-esteem, as needing help can be perceived as a failure of autonomy and self-management, potentially triggering feelings of shame and embarrassment (

Michelmore and Hindley 2012;

Lynch et al. 2025a). This perspective likely reflects broader Western cultural values that prioritise autonomy and self-reliance over help-seeking (

Bramesfeld et al. 2006), and the developmental drive for independence that young people understand to be a key marker of adulthood (

Arnett 2023;

Cooper 2018). Overall, young people were found to postpone help-seeking decisions until they judged it essential and the benefits outweighed the costs (

Biddle et al. 2007;

Chan 2013).

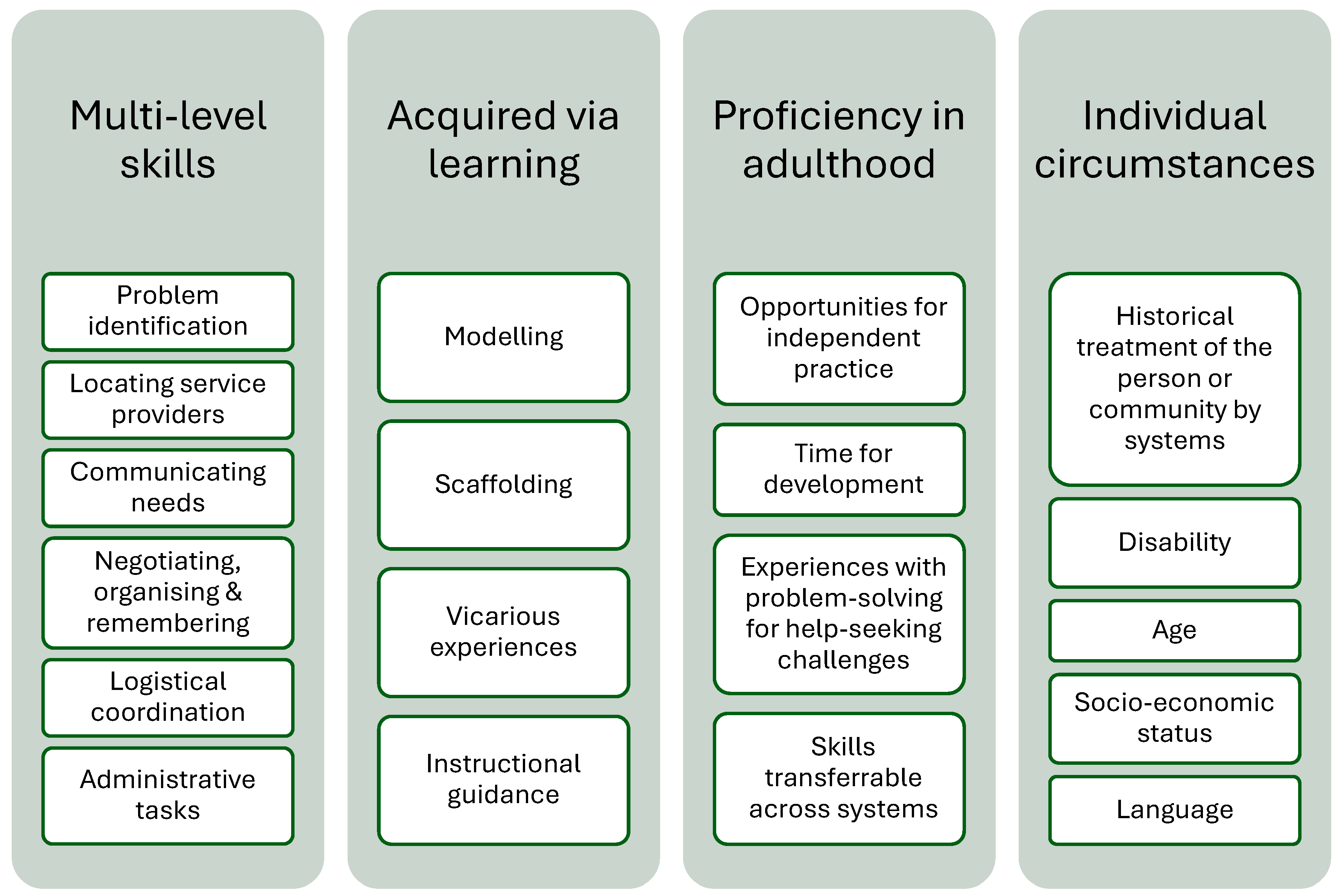

Young people reported that searching for help was challenging, particularly around knowing what type of help to search for or where to find it. Like decisions, searching processes were fluid and occurred concurrently with decision-making, as information or opportunities for support became available (

Chan 2013). Seeking professional help at a formal mental health service was found to require multi-level skills in communication, managing appointments and logistics, and confidence to interact with systems (

Rickwood et al. 2005). Findings from this research on how young people searched for help were analysed with findings from

Chan (

2013) and

Cornally and McCarthy (

2011), and a distinct set of formal help-seeking skills, visually represented in

Figure 4, was identified as required for people looking to search for, access, and attend a mental healthcare service.

This skillset is required to access many types of formal services in industrialised societies and can be acquired through observational learning and experience, with some degree of proficiency typically achieved by established adulthood. The necessity of such formal help-seeking skills presents a conundrum for young people who have not yet had the opportunity to develop them but still need to access and navigate mental healthcare systems. In emerging adulthood, findings suggest that young people can be more equipped for independent help-seeking than adolescents, but that family and friends continue to play a central role in providing the skills and resources needed to access healthcare and overcome system hurdles (

Breslin et al. 2021;

Boyd et al. 2007;

Moen and Hall-Lord 2019;

Lynch et al. 2023).

4.2. Social Contexts of Help-Seeking Processes

This research found that having a trusted social support was an essential precurser to formal help-seeking for young people, for four main reasons. First, friends and family could provide and model formal help-seeking skills and offer emotional support to attend treatment (

Michelmore and Hindley 2012;

Rowe et al. 2014). Second, being somewhat predictable and reliable in their responses, informal supports were easier to disclose to. Discussing painful feelings with unknown practitioners was particularly difficult for young people who had limited opportunities to assess potential helpers’ ability to respond in a non-stigmatising and supportive manner (

Coleman-Fountain et al. 2020;

Rickwood et al. 2005). Third, co-help-seekers could scaffold the formal help-seeking process, support disclosures to professionals, and share the impact of stigma or negative experiences, thereby reducing the overall stress for a young person already managing mental health problems. Finally, the central role of family and friends in successful professional help-seeking was highlighted by young people help-seeking alone. Young people with low social support, or who needed parental consent but wanted to avoid their family’s involvement, especially when their home environment contributed to their mental health problems, found help-seeking more challenging than those seeking help with supportive others. To navigate this, younger adolescents frequently spoke to semi-formal providers, such as teachers or youth workers, while withholding information that might trigger parental involvement. This form of independent help-seeking was typically indirect, with young people signalling to receptive adults that they wanted help through subtle changes in behaviour (

Bramesfeld et al. 2006). Independent help-seeking outside of social networks during later adolescence and emerging adulthood tended to be more successful in youth work or university settings, where formal supports were easily accessed.

Analysis of help-seeking patterns within social networks were found to differ across the life stage. Informal help-seeking to caregivers or other adults over friends was more common earlier in adolescence (

Lynch et al. 2023). Friends became more important in later adolescence and emerging adulthood, with their helpfulness being connected to their ability to relate and support formal help-seeking skills. Friends offered opportunities for peer learning, particularly around communicating, modelling, negotiating, or managing mental healthcare, as well as empathy, connection and care (

Eigenhuis et al. 2021;

Loureiro et al. 2013;

Lubman et al. 2016;

Medlow et al. 2010;

Westberg et al. 2020). Sharing stories of experiences with long delays or inadequate support helped set realistic expectations and provide protection from some of the more harmful impacts of the formal help-seeking process. This research found that all participants were impacted by suicide within their family, peer, or community networks, which might be related to the island’s relatively small size and social connectedness, the legacy of high youth suicide rates and, the ways in which suicide has shaped cultural understanding of mental health and help-seeking (

Bertuccio et al. 2024;

NOSP 2024). Stories of people who were unable to access help and subsequently died by suicide provided important vicarious learning, which could either encourage young people to continue looking for the help they needed to avoid similar outcomes or inspire hopelessness regarding the availability of help. In addition, having access to others with formal help-seeking skills did not always result in accessing help, as service barriers, including complex pathways, referral processes and waiting lists (

Lynch et al. 2025b), created obstacles. Young people also described how their informal supports were not always equipped with help-seeking skills and caregivers who had previous negative experiences with systems, marginalisation, economic or educational inequalities, or who were managing their own mental health problems, could struggle with supporting a young person with the help-seeking process (

Ellis et al. 2010;

Gilchrist and Sullivan 2006). When a young person could not locate a social support with these skills, the search for help often ended with a return to self-management (

Medlow et al. 2010;

Wilson and Deane 2012;

Burlaka et al. 2014;

Lynch et al. 2025b). These findings highlight the importance of accessible and supportive networks in facilitating help-seeking processes, linking with research by

Ungar (

2011) on how resilience is a dynamic process shaped by a young person’s social environment.

Some young people with multiple childhood adversities, low social support, and experiences of broken trust with adults avoided formal healthcare systems to protect themselves from further psychological harm. Participants emphasised their need for a lasting and committed relationship with a helper (

Loos et al. 2018), often seeking help through existing relationships within their community or school networks. Young people with experiences of marginalisation, including asylum seeking, being unhoused, and involvement with child protection or state care systems, typically became involved with the public healthcare system when they disclosed severe distress to a trusted helper (e.g., teacher, youth worker) who, recognising their professional or legal duty of care, referred them for help. Without time for observation or trust-building, young people described disclosing distress to GPs or mental health professionals in the hope of receiving help, support and care, while simultaneously anticipating judgement, embarrassment, disapproval, or negative consequences such as punishment and rejection (

Leavey et al. 2011), due to previous negative experiences with caregivers and systems. Navigating the public healthcare system involved the retelling of personal stories of pain to different adults during referrals, assessments and appointments, and was found to be a common adverse experience for young people, caused in part by inefficient administration and referral processes (

Lynch et al. 2025b). Some young people described feeling unsafe with professionals and formal service environments, which led to difficulties speaking, thinking or communicating effectively, and physical distress that included shaking from fear, sweating or vomiting. Essentially, help-seeking in these contexts triggered the human peritraumatic responses to trauma (

Katz et al. 2021), disproportionately affecting young people with experiences of statutory services, including immigration, the Gardaí (national police and security service) or social work involvement (

De Anstiss et al. 2009;

Masuda et al. 2009;

Kranke et al. 2012). To avoid involvement in these systems and further re-traumatisation, young people with experiences of marginalisation, who did not have access to private routes, prioritised self-reliance in the longer-term (

Medlow et al. 2010;

Wilson and Deane 2012;

Burlaka et al. 2014;

Lynch et al. 2025a). Young people identifying as LGBTI+ were found to avoid help-seeking to prevent further stigmatisation or for fear of being outed. Avoiding help-seeking as a mental health management strategy until distress became severe often resulted in in-patient care following suicide attempts. These findings highlight the urgent need to ensure that appropriate approaches are implemented in services encountering young people with experiences of marginalisation (

Damian et al. 2018;

Fish 2020;

Higgins et al. 2016;

Lynch et al. 2025a).

4.3. Reframing Youth Help-Seeking for Mental Health

This research has identified common patterns in how young people in this study approached mental health help-seeking, which can develop youth help-seeking theory. Considering the findings that informal help-seeking was an essential precursor to both service use and for learning formal help-seeking skills, young people described first observing for potential helpers or approaching a trusted adult or peer whom they had assessed as likely to provide support with distress and help-seeking. Viewed through a learning theory lens, these informal supports, who had experience of formal help-seeking, acted as

more knowledgeable others, modelling and/or scaffolding key help-seeking behaviours (

Wood et al. 1976). Through observing practical demonstrations, having discussions and sharing experiences, formal help-seeking skills were transferred to young people, who, given opportunities, practiced using them independently.

Figure 5 was developed from this research’s findings to illustrate this learning context for formal help-seeking skills within the framework of The Zone of Proximal Development (

Vygotsky 1978).

A comparative analysis of participants’ descriptions of their help-seeking processes for mental health problems with help-seeking behaviours described in educational learning help-seeking models (

Martín-Arbós et al. 2021) revealed similarities which are detailed in

Table 3.

Based on this analysis, understanding of mental health help-seeking patterns in young people can be improved by differentiating between

help-seeking as a pre-curser to learning, and

formal mental health help-seeking skills (

Figure 4), as the two concepts represent distinct actions and processes. In healthcare settings, help-seeking can be characterised as linear and episodic (

Cornally and McCarthy 2011), and pathways are profoundly shaped by services and involve assessments for access and appointments managed by practitioners or administrators (

Aday and Andersen 1974;

Lynch et al. 2025b). In educational contexts, help-seeking is best described as an iterative and dialectical process, where learners are supported to solve problems through an easily accessed helper, sometimes over multiple episodes (

Mathews and Mitrović 2008;

Martín-Arbós et al. 2021). This research found that young people’s initial approach to help-seeking for their mental health problems was analogous to how young people problem-solve in educational contexts, which may help explain common patterns of help-seeking to mental health services, reported as involving crisis or ad hoc approaches (

McGorry et al. 2019;

Rickwood et al. 2019;

Lynch et al. 2024). These patterns could be interpreted as instrumental learning actions: just enough service attendance (self-regulation) to receive support for distress (problem-focused engagement) to resume self-management (learning goal) (

Mathews and Mitrović 2008;

Martín-Arbós et al. 2021). From this learning perspective, young people’s mental health help-seeking processes can be viewed as normative, applying problem-solving schemas previously learned in educational or home environments (

Lynch et al. 2025a) and can also be reframed as developmentally appropriate learning and problem-solving approaches, with their learning goals including both mental health well-being and the development of a formal help-seeking skillset. Young people are agentic and self-regulating, engaging with cost–benefit analyses that inform decisions (

Martín-Arbós et al. 2021), and the preference for help-seeking within established informal networks (

Lynch et al. 2023) can be explained by alignment with existing help-seeking skills and capabilities. Friends and family offer easy, ongoing access to support that facilitates iterative and dialectical, or ‘ad hoc’, help-seeking. However, this style of instrumental problem-solving for mental health problems, when compared against the formal help-seeking approaches expected in healthcare, can make young people appear as lacking commitment or erratic. This can contribute to the labelling of young people in research as ‘reluctant’, ‘resistant’ or ‘avoidant’ to help-seeking, producing a misrepresentation of how they actually seek help. This ‘reluctance’ of young people to initiate help-seeking or their disengagement from a service can be alternatively viewed as a result of cost–benefit assessment, where young people deduce that a service or person might not be able to meet their individual learning or problem-solving needs. Furthermore, after multiple negative experiences, young people in this research assessed which supports did not meet their needs and moved to another service or individual whom they thought might better address their learning goals. Accordingly, the findings from this research support the interpretation that young people can be characterised as highly resourceful and resilient help-seekers, with specific mental health goals, actively engaged with their broader developmental and learning tasks.

4.4. Lasting Impacts of Help-Seeking

This research evaluated with young people how their experiences with help-seeking processes impacted their mental health and well-being. Young people had different expectations for mental health care, with some influenced by media depictions and psychotherapy stereotypes (

Goodwin et al. 2016), but they sought help to lower distress, increase self-management and improve well-being (

Cornally and McCarthy 2011;

Rickwood et al. 2005). For all, the search for help included the presumption that they would be helped, and this study found that many did not get the help they needed without multiple searches, sometimes over many years. Reports of positive experiences of ‘feeling helped’ included relief from distress, opportunities for expression, having distress validated, feeling respected, and reduced loneliness and stigma through connection with a helper (

Neilson et al. 2014;

Davison et al. 2017;

Samaritans 2019). Offloading was found to be particularly beneficial and supported self-management between meetings. Moreover, knowing that support and genuine care was available was found to have a therapeutic impact, temporarily boosting self-worth, and supporting self-management in the interim (

Davison et al. 2017;

Hackett et al. 2018). Positive help-seeking experiences with the right helper, especially when young people had previous negative experiences, reinforced the idea that help-seeking was an important resource in managing future distress and contributed to increased openness about mental health with friends, family, and even on social media, with young people promoting help-seeking to others. The impact of ‘feeling helped’ in the longer term resulted in improved self-awareness and self-management strategies, which contributed to personal growth, improved psychological stability and quality of life. Other positive impacts included feelings of personal power, self-efficacy, and security, which promoted optimism and hope (

McGorry et al. 2018). Experiencing a trusting, supportive rapport had a direct impact on young people’s lives, with young people repairing and building trust with others in their family and community networks. Helpful experiences supported the de-stigmatisation of help-seeking and reduced self-stigma and unhelpful self-labelling, with some participants reframing feelings of defectiveness, using compassionate or positive expressions of self and improved conceptualisations of mental health (

Bilican 2013;

Del Mauro and Williams 2013;

Eisenberg et al. 2012;

Lynch et al. 2025a;

Masuda and Boone 2011;

Prior 2012).

Negative help-seeking experiences caused young people further distress, often contributing to feelings of worthlessness and alienation, and reinforcing beliefs that their distress and problems were not valued. This research found that young people can disclose personal pain to adults in services and receive poor-quality support. Young people described negative interactions with helpers that caused them emotional injury, including a perceived lack of compassion or empathy (

Charman et al. 2010;

De Anstiss et al. 2009;

Gilchrist and Sullivan 2006). For care-experienced young people, negative and unempathetic responses from adults in services were found to reinforce childhood experiences of abuse, neglect, rejection and abandonment from caregivers, which were connected to feelings of defectiveness and helplessness (

Damian et al. 2018). Other reports included feeling stigmatised, judged, shamed, pathologised or blamed when a helper attributed their distress to a lack of effort or deliberate misbehaviour. In particular, clinical settings, assessments and personal information management practices could be violating to a young person and in-patient experiences could be re-traumatising, causing them to feel objectified, dehumanised, or scrutinised, linking with research from

Hackett et al. (

2018). These types of negative experiences were found to cause young people to internalise distress more deeply, increase negative self-labelling and reinforce beliefs about extreme self-reliance. This could also contribute to increased withdrawal of trust in others, mental health professionals and healthcare, and the help-seeking process, particularly for young people who previously used substances or self-harm to manage their distress (

Wilson et al. 2005;

Neilson et al. 2014). Negative help-seeking experiences led to some young people experiencing embarrassment and regret for having asked someone for help. These findings can offer some explanation as to why other studies have found that young people do not always seek help for their mental health problems and why negative experiences impact future help-seeking (

Mackenzie et al. 2014;

Purcell et al. 2011;

Rickwood et al. 2005). Importantly, these findings highlight how inappropriate service provision can contribute to hopelessness, loneliness and suicidal pathways, and emphasises the urgent need for youth-centred and trauma-informed mental healthcare (

Damian et al. 2018;

Crosby et al. 2018;

Lynch et al. 2024;

Samaritans 2019).

4.5. Limitations

This research was conducted in the Northwest of Ireland and, while it increases understanding of young people’s help-seeking processes, the findings may only be relevant or transferable to other high-income countries with Western cultural influences and public and private healthcare systems that have similar access structures. During recruitment, it was not possible to recruit young people from the Traveller or Roma communities, who are typically absent from mental health research in Ireland (

Fanning 2012). Additionally, requiring parental consent for participants under 18 may have impacted decisions to take part.

4.6. Recommendations

This study identified important patterns in young people’s mental health help-seeking processes, providing critical discussion on the need to distinguish between help-seeking as a precursor to learning and as a formal help-seeking skill set, thereby enhancing theoretical understanding of how young people access professional support. Future research can continue to examine young people’s lived experiences of mental health help-seeking and consider the central, embedded role of others within their social networks. Considering learning and ecological frameworks alongside models using the Theory of Planned Behaviour can provide further insight into help-seeking processes in Western healthcare systems. Additionally, this can support the development of youth-specific models or frameworks that reflect socially embedded approaches and age-related help-seeking strategies across the developmental period of youth. Advancing help-seeking theory by acknowledging youth help-seeking approaches as typical and developmentally normative can improve how young people are supported to engage with services and ensure that access and provision aligns with their developmental capabilities.

Policymakers and practitioners can consider how services can be revised to facilitate easier access for young people in ways that are developmentally aligned and inclusive of both those co-help-seeking with families or attempting independent help-seeking. Trauma-informed approaches are urgently needed, considering that young people in most need of support can be the most adversely impacted by inappropriate service provision. Improved service design can avoid further harm or re-traumatisation of young people asking for help (

Long and Lynch 2025), a finding that has been reported in other countries with similar mental healthcare systems (

McGorry et al. 2011,

2019). Referring practitioners can consider the capacity of a service to respond appropriately before referring young people on, particularly for those experiencing marginalisation. Finally, feedback and evaluation are essential to ensure that services and interventions are experienced as helpful by young people, and that provision supports equitable access to healthcare as well as positive mental health and well-being outcomes.

4.7. Conclusions

This study found that young people’s help-seeking processes were varied, multi-episodic and socially embedded. Help-seeking decisions and searches were found to be complex and fluid, involving cost–benefit analyses and input from important external factors, such as access to a supportive other and the availability of services. Independent help-seeking was constrained by formal mental health service design, which required formal help-seeking skills, and successful help-seeking during youth required support from a friend or family member with these skills. Help-seeking patterns during youth were found to be similar to how young people problem-solve within educational contexts, which can impact how researchers and practitioners view youth approaches to help-seeking for their mental health problems. The impact of help-seeking had lasting effects, either directly supporting growth and improving well-being, or further entrenching distress. The experience of ‘feeling helped’ was rare, seldom occurring on the first attempt, and typically only after many help-seeking episodes. Young people should only be encouraged to seek help to providers that can offer appropriate healthcare, as this research has demonstrated that help-seeking can cause re-traumatisation, increase distress or contribute to suicidality. To minimise harm and improve provision and outcomes for young people’s health, education, and employment, research needs to urgently address the theoretical gap by developing distinct youth mental health help-seeking models or frameworks that acknowledge and incorporate how young people decide, search, and ask for help, and the important social relationships that support this process.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L.; methodology, L.L., A.M. and M.L.; formal analysis, L.L.; investigation, L.L.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L.; writing—review and editing, L.L., A.M., M.L. and I.H.-S.; supervision, A.M., M.L. and I.H.-S.; project administration, L.L. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Ulster University (protocol code 180010 and 1 June 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study cannot be shared openly to protect participant privacy and participants did not consent to data availability.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction in the Abstract. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Aday, Lu Ann, and Ronald Andersen. 1974. A Framework for the Study of Access to Medical Care. Health Services Research 9: 208–20. [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre Velasco, Antonia, Ignacio Silva Santa Cruz, Jo Billings, Magdalena Jimenez, and Sarah Rowe. 2025. What are the barriers, facilitators and interventions targeting help-seeking behaviours for common mental health problems in adolescents? A systematic review. Focus 23: 98–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, Icek. 1991. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50: 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen. 2023. Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens Through the Twenties, 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barbour, Rosaline S., and Michael Barbour. 2003. Evaluating and Synthesizing Qualitative Research: The Need to Develop a Distinctive Approach. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 9: 179–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertuccio, Paola, Andrea Amerio, Enrico Grande, Carlo La Vecchia, Alessandra Costanza, Andrea Aguglia, Isabella Berardelli, Gianluca Serafini, Mario Amore, Maurizio Pompili, and et al. 2024. Global trends in youth suicide from 1990 to 2020: An analysis of data from the WHO mortality database. EClinicalMedicine 70: 102506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, Olivia, and Sun Ban. 2021. Adolescence: Physical Changes and Neurological Development. British Journal of Nursing 30: 272–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddle, Lucy, Jenny Donovan, Deborah Sharp, and David Gunnell. 2007. Explaining Non-Help-Seeking amongst Young Adults with Mental Distress: A Dynamic Interpretive Model of Illness Behaviour. Sociology of Health & Illness 29: 983–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Bilican, Isil. 2013. Help-Seeking Attitudes and Behaviors Regarding Mental Health among Turkish College Students. International Journal of Mental Health 42: 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilsen, Johan. 2018. Suicide and Youth: Risk Factors. Frontiers in Psychiatry 9: 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, Cathy, Kate Francis, Dianne Aisbett, Karen Newnham, Janet Sewell, Graham Dawes, and Sue Nurse. 2007. Australian Rural Adolescents’ Experiences of Accessing Psychological Help for a Mental Health Problem. Australian Journal of Rural Health 15: 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramesfeld, Anke, Lisa Platt, and Friedrich Wilhelm Schwartz. 2006. Possibilities for Intervention in Adolescents’ and Young Adults’ Depression from a Public Health Perspective. Health Policy 79: 121–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslin, Gavin, Stephen Shannon, Garry Prentice, Michael Rosato, and Gerard Leavey. 2021. Adolescent Mental Health Help-Seeking from Family and Doctors: Applying the Theory of Planned Behaviour to the Northern Ireland Schools and Wellbeing Study. Child Care in Practice 28: 522–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Psychological Society. 2014. Code of Human Research Ethics 2014. Available online: http://www.bps.org.uk/the-society/code-of-conduct/ (accessed on 5 March 2017).

- Bryman, Alan. 2012. Social Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burlaka, Viktor, Iuliia Churakova, Olivia A. Aavik, Karen M. Staller, and Jorge Delva. 2014. Attitudes toward Health-Seeking Behaviors of College Students in Ukraine. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 12: 549–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]