Abstract

The objective of this paper is to analyze the European Union’s response to school bullying and cyberbullying through its educational policies. For this purpose, a search of European policies was carried out in EUR-Lex, including all dates, to get a complete picture of this phenomenon. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 16 policies were selected. These were analyzed, according to Content and Documentary Analysis, using MAXQDA Analytics Pro 2024 through a codebook composed of two dimensions: one legal and one specific to bullying and cyberbullying. The results showed that most of these policies are soft policies, especially recommendations, issued by the Council of the European Union. At the same time, there is an interest on the part of the European Union to prevent bullying by addressing the contextual and cultural risk factors and improving teacher training and emotional education. In conclusion, European policies have a largely technological, preventive, and contextual and cultural approach. Finally, this paper also offers some policy recommendations to prevent school bullying and cyberbullying in political terms.

1. Violence, Bullying, and Cyberbullying in the European Union

The issue of violence and bullying in educational institutions represents a significant concern for the countries of the European Union, given its deleterious impact on students’ physical and emotional well-being, as well as their academic and social development (UNESCO 2019; Lorenzo and Iglesias 2022). This phenomenon violates children’s rights (Andrews et al. 2023; Mayasari and Atjengbharata 2024). It should be noted that nation-states must guarantee the three pillars of children’s rights (Ruiz-Casares and Collins 2016; Heimer et al. 2017): provision, protection, and participation. These recognize the obligation of nation-states to ensure children’s access to health, education, and play (provision). It also recognizes their right to actively participate in any process that affects their well-being and personal development (participation). Finally, countries must protect children from any type of violence and/or discrimination (protection), although this is a task shared by the community (Ruiz-Casares and Collins 2016).

In this context, significant studies have been conducted over the last five years, providing crucial data on the prevalence of the phenomenon, the profiles of those involved, and the preventive measures implemented in various countries.

Bullying is the set of actions sustained over time by a person or group of people against another person, who is usually in a situation of vulnerability, with the intention of harming him/her by asserting their position of power (Lorenzo and Iglesias 2022). On the other hand, cyberbullying is deliberate aggressive behaviors perpetrated through technological means, with the intent to cause harm to the victim. A distinguishing feature of cyberbullying is the use of technology as the medium for these actions, which can take a repetitive and continuous form, exacerbating the sense of helplessness experienced by the victim. It encompasses a wide spectrum of behaviors, including the transmission of aggressive and threatening messages, social exclusion, the propagation of falsehoods, and the misappropriation of personal information for malicious purposes. The prevalence of cyberbullying exhibits variation depending on the definition employed and the age group under study, with estimated global ranges from 6.5% to 72%. In Europe, considerable variability is also observed in the rates across different studies (UNESCO 2019).

According to recent data from studies by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2023) and the World Health Organization (2021), approximately one in three students aged 11 to 15 in the European Union has experienced some form of bullying or violence in school over the past year. The prevalence of this phenomenon varies across countries, ranging from 15% in countries like Finland and Sweden to approximately 35% in Bulgaria and Romania. The European Commission’s report (Eurydice 2022) also highlights a notable increase in cyberbullying, with figures suggesting that between 10% and 15% of European students have experienced bullying through digital means in the last year.

Recent European literature (Menesini and Salmivalli 2017; Romera et al. 2022) provides clear and differentiated profiles of victims, perpetrators, and bystanders. Victims tend to exhibit common characteristics such as shyness, insecurity, low self-esteem, and a lack of social support networks. It is also observed that students belonging to ethnic minorities, those with disabilities, or those belonging to the LGTBIQ+ community are more vulnerable to school bullying.

In more detail, some authors (Menesini and Salmivalli 2017) point to the following risk factors and divide them into different categories: individual, classroom-level, and contextual and cultural-level. Regarding individual risk factors, perpetrators tend to have an aggressive personality pattern and a general tendency toward aggression (Lorenzo and Iglesias 2022). In this line, they manifest narcissistic attitudes and cognitions that favor aggression and low levels of empathy. Also, they establish relationships of domination-submission with others, often motivated by an authoritarian and low-cohesion family environment. In the case of victims, they have low levels of assertiveness and high levels of insecurity. They tend to be physically weak, with a limited network of friends, who show traits of shyness and who have an overprotective family environment.

At the classroom level, bullying is more likely to occur in authoritarian environments where violent attitudes are made invisible or reinforced by the teacher and the group. Finally, there are several contextual and cultural factors that increase the risk of bullying. This is the case of children belonging to cultural, religious, and linguistic minority groups and vulnerable groups (children with disabilities, refugees, migrants, etc.). In short, being different increases the risk (Lorenzo and Iglesias 2022). On the contrary, we could affirm that traits contrary to the above are considered protective factors (De la Plaza Olivares and González 2019).

In sum, regarding perpetrators, research conducted by Menesini and Salmivalli (2017) and Smith et al. (2016) indicates that they tend to have emotional regulation problems, prior antisocial behaviors, low empathy, and a positive perception of using violence as a means to resolve conflicts or gain popularity.

In the other way, witnesses are a crucial group and represent about 80% of the student body. Recent studies (Romera et al. 2022) highlight the importance of working with this collective to break the cycle of violence, as their intervention can significantly reduce violent behaviors and provide effective support to victims.

2. Effectiveness of Anti-Bullying Programs

A widely cited meta-analysis (Gaffney et al. 2019), which encompassed 100 independent evaluations of anti-bullying programs, concluded that on average, these programs managed to decrease bullying perpetration by approximately 19–20% and victimization by approximately 15–16% compared to schools without intervention (Borgen et al. 2021). This confirms that the initiatives have a significant effect; however, a substantial part of the problem remains unresolved (e.g., a 20% reduction in perpetrators implies that 80% of those who bullied may continue doing so). Nonetheless, these averages include cases of weak implementations; the best-applied programs achieved higher reductions. For example, in some controlled studies, KiVa achieved a drop of up to 40% in the proportion of victims in primary schools, while the Olweus program reported up to 50% less bullying in certain pilot schools (Gaffney et al. 2021). The variability is considerable: there were contexts where the same program had minimal effect, likely due to issues in implementation fidelity (untrained personnel, lack of institutional support, etc.). An interesting finding from the meta-analysis was that certain components increased effectiveness: schools that integrated a whole-school approach, established explicit anti-bullying norms, worked with parents, and involved peers informally showed higher reductions in bullying. This reinforces the idea that only multidimensional approaches achieve substantial changes.

Accordingly, this systematic review compared results by countries and specific programs (Gaffney et al. 2019). It found, for example, that evaluations conducted in Scandinavian countries tended to be especially effective in reducing victimization (perhaps due to their tradition of school coexistence), while in some Mediterranean countries, notable improvements were observed in reducing perpetrators. In terms of programs, it was highlighted that the Olweus Program generated, on average, the greatest effects in reducing bullying behaviors by perpetrators, and the Italian NoTrap! program was the most effective in reducing the number of students reporting being victims. KiVa also showed solid effects, although variable depending on age (more in primary education). This suggests that not all programs affect all aspects in the same way: some may be better at preventing students from bullying (e.g., through discipline and clear norms), while others achieve fewer students being victimized (e.g., by empowering potential targets and defenders).

Despite the specific successes, significant challenges persist. One of them is the sustainability of effects: several studies find that improvements in bullying rates tend to diminish over time if the program is not continuously reinforced. A school may see a drop in cases the year it intensively implements an initiative, but if the priority drops the following year or there is turnover of trained personnel, the problem could reappear. Therefore, experts insist that bullying prevention cannot be a one-time effort but a permanent part of the school culture. Another challenge is cultural transferability: a program designed in one context may not fit equally well in another. For example, KiVa had a huge impact in Finland in bullying and cyberbullying (Williford et al. 2013; Herkama and Salmivalli 2018), but in trials in other countries, its results were more modest, possibly due to differences in the way teachers implemented it or in local social dynamics. Adapting materials to the language is not always enough; examples need to be tailored, communities need to be involved, etc.

It has also been observed that many programs focus on the primary stage or early years of secondary education, achieving their main successes there, but lose effectiveness with older adolescents. Students aged 16–18, for example, may be more skeptical of certain activities and require differentiated approaches (more horizontal dialogue, addressing issues such as sexual or relationship bullying, etc.). This gap suggests expanding or designing specific strategies for high school and vocational training, levels where bullying exists though sometimes invisibilized.

A critical aspect is the training of teachers and school staff. Without the commitment and skills of adults in the school, even the best program on paper will fail. Many researchers still report shortages in systematic training of teachers to handle bullying (Novo et al. 2021; Castellanos et al. 2022). Moreover, turnover of principals or teachers can disrupt processes. Schools that implement successfully often have one or several internal “champions”—teachers, counselors, or directors highly committed to the issue—who lead and motivate the rest (Låftman et al. 2017). When these figures are lacking, implementation can become bureaucratic and ineffective.

Another growing challenge is integrating cyberbullying prevention. Most classic programs focused on the face-to-face school environment. While some have added modules on cyberbullying, this phenomenon has particularities (anonymity, 24/7, virality) that require also involving parents and the digital community. Recent initiatives like FUSE in Ireland or the Spanish program “Asegúrate” (Del Rey et al. 2019) are steps in this direction, but clear evidence is still lacking on which online strategies work best to complement offline actions.

3. Materials and Methods

After exploring some anti-bullying programs, it is time to explain the research method. This paper was developed using two methods: Content and Documentary Analysis. These methods deal with studying any written or spoken resource (Renz et al. 2018). Therefore, they could be used to analyze press news, textbooks, advertisements, podcasts, public and political speeches, among others (Mayring 2014; Stemler 2015). Through the analysis of the information collected in these documents, different categories are established (Kleinheksel et al. 2020; Paljakka 2024). It allows the following things: (1) to make a synthesis of all documents (Braun and Clarke 2006); (2) to generate new knowledge on the studied field (Jiménez et al. 2017); and, finally, (3) to interpret the phenomena from a scientific and systematized perspective (Krippendorff 2019).

These reasons, and the high accessibility of these methods (Kleinheksel et al. 2020), have increased their application in the field of research. Some recent papers have employed this method to study bullying (Paljakka 2024) and educational policies (Neubauer 2023, 2025), but from different perspectives. In turn, Hellström and Beckman (2020), through focus groups and using content analysis, identified students’ perceptions of bullying in boys and girls from a gender perspective. Bintz (2023) delved into the representation of bullying in textbooks. Also, Vaill et al. (2020) published a paper where they analyzed anti-bullying policies in Australia. Finally, Paljakka (2024) has used the MAXQDA analysis software to study bullying, coinciding with the proposal put forward in our research.

3.1. Objectives and Research Questions

The objective of this paper is to analyze the European Union’s response to school bullying and cyberbullying through its educational policies.

In line with this objective, two research questions have been posed. The first one takes as a reference the studies of Matarranz (2017) and Neubauer (2023), who analyze the legal nature of European educational policies and their influence on national policies. In this regard, the following research question (RQ) has been formulated:

- (RQ1) What kind of policies does the European Union issue on bullying and cyberbullying?

Following the research of Rubio Hernández et al. (2019), this paper tries to answer the second question:

- (RQ2) How do European policies constrain or enable anti-bullying implementation?

3.2. Search of Information

Documents have been searched in EUR-Lex. This is an official legal database where all European policies are collected and published. In this platform, different searches were carried out using these common criteria:

- Exclude corrigenda: True.

- Choose multiple collections: treaties, legal acts, consolidated texts, lawmaking procedures.

- Date: All dates.

Later, four searches were carried out in order to obtain the most comprehensive representation of the treatment of bullying in European policies. For this purpose, the following criteria were applied (see Table 1):

Table 1.

Search criteria used in EUR-Lex.

After the application of exclusion criteria (“C1. Repeated policies” and “C2. Issues not related to bullying”), 16 policies were selected. Subsequently, the documents were subjected to a quality analysis. The following criteria were taken into account (see Table 2):

Table 2.

Results of the document quality analysis.

- Clarity of objectives.

- The target group.

- Whether there is a monitoring system in place to evaluate the policy’s achievements.

- The coverage of the code in the document, which was carried out with MAXQDA. This analysis made it possible to categorize in quartiles the intensity with which bullying and cyberbullying are addressed throughout the document. Thus, a “very low” value was assigned to the first quartile, a “low” value to the second, a “strong “value to the third, and a “very strong” value to the fourth.

3.3. Instrument and Procedure for Data Analysis

To collect and analyze these documents, a codebook has been designed. It has been elaborated based on Rubio Hernández et al. (2019), who analyzed the regional Spanish policies on school bullying and cyberbullying. On the other hand, the legal analysis was based on Neubauer (2023). In turn, based on previous research (Matarranz 2017; Neubauer 2023), codes have been established from an inductive–deductive process. For that reason, in an initial stage of the codebook design process, previous studies in the dimensions of legal analysis (Matarranz 2017; Neubauer 2023) and bullying and cyberbullying (Rubio Hernández et al. 2019) were taken as a reference. Later, through the reading of the texts some codes emerged, especially those related to risk factors identified by Menesini and Salmivalli (2017), which were added to the codebook. That said, the following codebook was the final result (see Table 3):

Table 3.

Codebook.

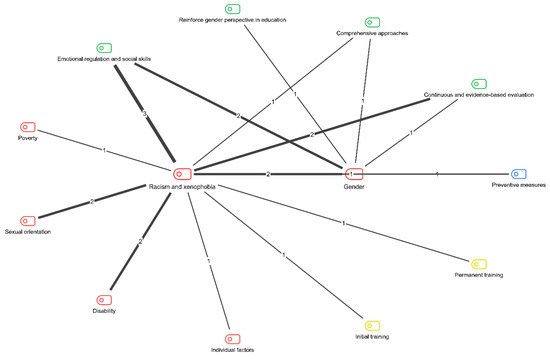

Once the instrument was designed, a coding process was performed in MAXQDA Analytics Pro 2024. Later, two types of analysis were carried out: a code x document set matrix (see Table 4 and Figure 1) and a code co-occurrence model (see Figure 2).

Table 4.

Legal characteristics of the policies.

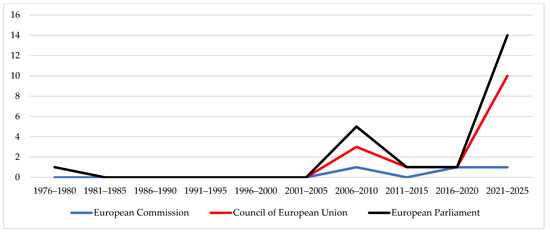

Figure 1.

Evolution of anti-bullying policies. Note. This figure shows the number of anti-bullying policies that have been issued by each EU institution over time. In this case, it should be clarified that some documents are issued jointly by two or three institutions.

Figure 2.

Co-occurrence of codes “Racism and xenophobia” and “gender”. Note. The thickness of the lines represents the intensity with which two codes have coincided in the same paragraph.

4. Results

After having explained the method, the results obtained from the analysis of the 16 policies are presented below. To begin with, it is necessary to detail the legal characteristics of the policies analyzed. In this regard, these are mainly soft policies (60%). It means that they are not mandatory for Member States. Among them, recommendations (40%) are the main legal instrument used by the European Union. In the soft policies, there are other kinds of documents (conclusions and resolutions), but their representation is residual. On the other hand, regulations (20%) are the most common legal instrument in hard policies. In addition, the European Union has issued two directives (13.33%) and one decision (6.67%) addressing the phenomenon of bullying.

From another point of view, these documents were mainly issued by the Council of the European Union (59.09%). In second order, the European Parliament (27.27%) and in third the European Commission (13.64%) were responsible of these policies. In this regard, it should be noted that seven documents have been issued jointly by more than one of these institutions.

The table above shows how the publication of policies related to school bullying by the European Union has intensified in recent years. However, it has been a permanent interest in the subject since 2006, but after the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of policies on bullying has increased significantly.

On the other hand, the main themes developed in these documents are varied. For example, issues related to gender, sustainability, citizenship, and the functioning of European policy are addressed (5.56%), but briefly. In turn, digitalization (16.67%) and children’s rights (11.11%), both related to school bullying and cyberbullying, are more represented.

More specifically, educational policies are focused on topics as early school leaving, digital education and inclusive education. Although only 1 document directly addresses bullying, the 16 analyzed documents reference the topic 45 times.

Nevertheless, bullying is named (27 Cod.) in more quotes than cyberbullying (18 Cod.). In this line, the “Council Resolution on a strategic framework for European cooperation in the field of education and training, towards the European Education Area and beyond (2021–2030)”, recommend to Member States to “maintain education and training institutions as safe environments, free from violence, harassment, harmful speech, misinformation and any form of discrimination” (Council of the European Union 2021c, p. 17). This is repeated in the case of cyberbullying. For that reason, the European Union points out that “children have to be protected in both physical and digital environments from risks such as (cyber-)bullying and harassment” (European Commission 2024, p. 5). Thus, it considers it fundamental to “reduce the amount of illegal content circulated online and deal adequately with harmful conduct online, with particular focus on online distribution of child sexual abuse material, grooming and cyber-bullying” (European Parliament and Council of the European Union 2008, p. 6).

In this sense, the European Union is in favor of implementing a preventive approach to bullying. Accordingly, its policies have many references to this idea (10 Cod.). Among them, the “Council Conclusions of 22 September 1997 on safety at school” (Council of the European Union 1997) highlights because it affirms that “school may include strategies to prevent and to combat intimidation, bullying and abuse (for pupils/students as well as teachers)” (p. 1). In consequence, it suggests that “specific attention should be paid to preventive and curative aspects of safety at school as well as to the development of explanations of violence at schools and to the school in its environment” (Council of the European Union 1997, p. 2). On the other hand, these policies are mainly focused on victims of bullying. The need to carry out an early intervention in bullying aggressors is only mentioned once (Council of the European Union 2022).

From another point of view, European policies try to make visible and minimize the impact of risk factors of victims (27 Cod.) because they increase their vulnerability. This supranational organization identifies some of them. One is having suffered bullying or lived a traumatic experience in the past (1 Cod.) (Council of the European Union 2022). However, the main risk factors are those associated with place of origin, ethnicity, and gender. The latter is the one most present in European policies (11 Cod.). As a result, the European Union affirms that

particular attention will be devoted to promoting girls’ education and safety at school. Support will be provided to the development and implementation of nationally anchored sector plans as well as the participation in regional and global thematic initiatives on education.(European Parliament et al. 2006, p. 15)

In turn, one of the main concerns of this organization is to fight against racism and xenophobia (8 Cods.). As an example, Roma people, as other collectives, suffer from these phenomena. To solve that, the European Union suggests implementing

measures to effectively fight direct and indirect discrimination, including by tackling harassment, antigypsyism, stereotyping, anti-Roma rhetoric, hate speech, hate crime and violence against Roma, including incitement thereto, both online and offline.(Council of the European Union 2021a, p. 6)

However, the quotes analyzed about ethnocultural factors are linked to other contextual and cultural risk factors. These include being a disabled (2 Cods.), poor (1 Cod.), and/or LGTBI+ (2 Cods.) person, as Figure 2 shows.

This is reflected in the following quote, where all the factors mentioned above are interrelated. Hence, the European Union suggests carrying out

support actions to prevent and combat all forms of discrimination, racism, xenophobia, afrophobia, anti-Semitism, anti-Gypsyism, anti-Muslim hatred, and allforms of intolerance, including homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, interphobia and intolerance based on gender identity, both online and offline, as well as intolerance of persons belonging to minorities, taking into account multiple discrimination. In that context, particular attention should also be devoted to preventing and combating all forms of violence, hatred, segregation and stigmatisation, as well as to combating bullying, harassment and intolerant treatment.(European Parliament and Council of the European Union 2021, pp. 4–5)

From an intersectional perspective, the relationship between gender and ethnocultural factors is also present in European policies. In this way, the European Union recognizes how vulnerability increases exponentially in those people who have some of these contextual and cultural characteristics simultaneously. Consequently, this supranational organizations warns about the importance of “stimulating a safe and supportive school environment as a necessary condition for concrete issues, such as tackling discrimination, racism, sexism, segregation, bullying (including cyber-bullying), violence and stereotypes, and for the individual well-being of all learners” (Council of the European Union 2021c, p. 17).

Taking into account these issues, the European Union considers it key to strengthen teachers’ training (4 Cods.). As a result, it suggests integrating “inclusion, equity and diversity, understanding underachievement and disengagement, and addressing well-being, mental health and bullying in all statutory initial teacher education (ITE) programmes” (Council of the European Union 2022, p. 12).

Likewise, this supranational organization offers some guidelines for developing anti-bullying programs. One of its main lines is to promote students’ emotional and social skills (13 Cod.). To this end, they based on previous research to affirm “the importance of emotional, social and physical well-being in schools to enhance children and young people’s chances of succeeding in education and in life” (Council of the European Union 2022, p. 2). This is essential because “violence and bullying, racism, xenophobia and other forms of intolerance and discrimination, have devastating effects on children’s and young people’s emotional well-being and educational outcomes”, especially in vulnerable people (Council of the European Union 2022, p. 2). Thus, the European Union invites Member States to promote emotional education and provide psychological support to children (European Commission 2024).

Also, it recommends the implementation of programs such as counselors and mentors (1 Cod.) to address cases of bullying (Council of the European Union 2022). It also warns of the importance of reinforcing the gender perspective in education because it can contribute to reducing school and sexual harassment (Council of the European Union 2021c), especially online. In consequence, it suggests

incorporating a gender-sensitive approach, will aim to better understand the psychological, behavioural and sociological effects of online technologies on children, ranging from the effect of exposure to harmful content and conduct, to grooming and cyber-bullying across different platforms, from computers and mobile phones to game consoles and other emerging technologies.(European Parliament and Council of the European Union 2008, p. 8)

However, the European Union promotes the adoption of comprehensive approaches (9 Cods) to bullying. In this line, it claims the relevance of involving families, educational authorities, health professionals, civil organizations, and the local community in the education of children and adolescents (Council of the European Union 2011; Council of the European Union 2022; European Commission 2024). It affirms that “noting that it is important to involve parents, pupils/students, teachers, headteachers and local agencies and their organizations at European and Member State level in activities in this field [bullying]” (Council of the European Union 1997, p. 1). For that reason, the European Union suggest the creation of “contact points where parents and children can receive answers to questions about how to stay safe online, including advice on how to deal with both grooming and cyber-bullying” (European Parliament and Council of the European Union 2008, p. 5). This, in turn, will be complemented by “the provision of information on how to report and intervene in cases of bullying, how to seek help and support and how to reverse abusive and toxic behaviour” (European Commission 2024, p. 12).

At the same time, the European Union recommends the use of ICT to prevent and combat cyberbullying. Indeed, it recognizes that misinformation and hate speech (Council of the European Union 2024) in the digital sphere increase the risk of bullying. Therefore, this supranational organization calls for strengthening the digital competencies of the educational community

to enable the appropriate understanding of digital technologies and meaningful, healthy, safe, and sustainable engagement with digital and other relevant technologies and their functioning, including generative AI systems. Safe individual and collective practices that tackle the risks of hyperconnectivity and cyberbullying, especially those faced by vulnerable groups, should also be encouraged.(Council of the European Union 2024, p. 6)

Finally, it invites Member States to carry out periodical and evidence-based evaluations of these programs (5 Cods.) to ensure the physical and mental well-being of the educational community (Council of the European Union 2021b).

5. Discussion

After presenting the results, it is time to answer the research questions. Regarding the first one (RQ1. What kind of policies does the European Union issue on bullying and cyberbullying?), the data show how most of these documents are soft policies and, more specifically, recommendations. This is in line with other previous papers (Matarranz 2017; Neubauer 2023) that have studied the European Union’s educational policies. Likewise, the increase in policies related to bullying and cyberbullying answers to the need to respond to this emerging phenomenon following the pandemic and the rise of social networks (Eurydice 2022; Bachmeier and Cardozo 2024). In turn, the diversity of the main themes of these policies shows that bullying and cyberbullying are cross-cutting social phenomena that go beyond the boundaries of the school and the education system. So much so, the European Union must adopt a more explicit position on this phenomenon. So much so that the intensity with which bullying and cyberbullying are addressed is lower, as they only occupy more than 10% of the document in three of the 16 policies analyzed. As sample, only one of the policies analysed focus on bullying and cyberbullying in a monographic way. Due to the educational, social, and technological changes since the publication of this policy, it is necessary to design a European framework for anti-bullying, and anti-cyberbullying. In turn, this framework must have an explicit and binding evaluation and monitoring system. This article shows that this measure is only integrated into six of the 16 policies analyzed, despite being identified as a key element.

On the other hand, and answering the second research question of this paper (RQ2. How do European policies constrain or enable anti-bullying implementation?), it is observed how predominates a protective approach towards children in European anti-bullying policies (Ruiz-Casares and Collins 2016; Heimer et al. 2017). While the provision of the right to education seems to be guaranteed, child protection presents some relevant challenges. One of them is cyberbullying (United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child 2021; Lesko et al. 2021), which despite being a growing phenomenon across Europe, has a lower presence in the policies analyzed than traditional bullying. This alerts about the need for the European Union to align its policies with the current digitalization context that increases the risk of cyberbullying (Eurydice 2022). Cyberbullying is often closely linked to the proliferation of hate speech on social networks (Council of the European Union 2024), pornography, and child sexual harassment (European Parliament and Council of the European Union 2008). However, the threats and challenges posed by artificial intelligence to children’s rights have also been highlighted in recent years (Council of the European Union 2024; European Commission 2024). To face these emerging challenges, it is essential to implement the whole-school approach in anti-bullying policies (Council of the European Union 2011; Council of the European Union 2022; European Commission 2024). Families and the community have positioned themselves as key actors in preventing and combating bullying (Del Rey et al. 2019). That is why, it is essential to take advantage of the potential of ICT as a support resource and to equip the educational community with competencies and digital literacy. In this line, the European Union has promoted some actions aimed at fostering digital literacy through programs such as the EU Digital Services Act and the Safer Internet Program.

Another relevant aspect identified by the European Union is to promote emotional education, since it would contribute to reinforce the protective factors of children (Smith et al. 2016; De la Plaza Olivares and González 2019; UNESCO 2019; Lorenzo and Iglesias 2022). However, these policies focus on victims, making intervention with aggressors and witnesses invisible, which may jeopardize the principle of non-discrimination at school.

From another point of view, there is little reference to child participation in European policies, as it is only encouraged through the mentoring program (Council of the European Union 2022). Consequently, it would seem advisable to strengthen the participation of children in the design, implementation and evaluation of these policies in the future.

At the same time, it is relevant to reinforce teacher training on bullying and cyberbullying in European policies. This is a remarkable fact for several reasons (Låftman et al. 2017; Novo et al. 2021; Castellanos et al. 2022):

- Some research has concluded that teachers have little training in this area.

- Teachers have been identified as a key actor not only to ensure the well-being of children, but also the quality and the right to education.

- The attitude, praxis, and classroom management of teachers are variables that directly affect risk and protective factors in the classroom level.

The documents analyzed reflect how risk factors are unevenly represented. So much so that most references are to the contextual and cultural level (Menesini and Salmivalli 2017). In this sense, the European Union adopts an intersectional approach (Crenshaw 1991) and recognizes that people who bring together characteristics different from the normative are more vulnerable to being victims of bullying (Migliaccio 2022). This aligns with previous research where the influence of contextual factors in bullying and cyberbullying cases is recognized (Swearer et al. 2006). For that reason, bullying has to be approached from a socio-ecological perspective, so as to make visible the relations of domination and power in society (Donogue and Pascoe 2023).

Another focus of concern for the European Union is the implementation of monitoring and evaluation mechanisms for anti-bullying policies. This recommendation is important to be implemented by nation-states, as anti-bullying programs sometimes lose effectiveness over time (Gaffney et al. 2019).

With all this, it is necessary to break the cycle of violence (Romera et al. 2022). A priori, the European Union is in favor of putting an end to it through anti-bullying policies, which have proven to be effective at the international level (Gaffney et al. 2019; Borgen et al. 2021). However, the European Union has a largely contextual and cultural, technological, intersectional, and preventive approach in anti-bullying policies that can inspire Member States.

Despite this, the European Union’s position presents some sensitive areas for improvement. On the one hand, it refers to general measures, but these are not very specific in practice. This, added to the lack of competencies in education of the European Union, hinders the implementation of these policies in schools. One way to solve this aspect would be to build a common European anti-bullying program based on successful programs as Kiva or Olweus. In this way, the emerging challenges caused by artificial intelligence and cyberbullying in terms of children’s rights could be addressed. These rising phenomena are underrepresented in European policies. For this reason, the positioning of this organization is politically correct, but it is mainly symbolic.

Finally, it should be noted that this paper has some limitations. The first is that the coding has been carried out by two studies. Maybe, it would be convenient to include a third to triangulate the data analysis. On the other hand, the policy analysis provides an framework at the European level, but does not analyze how it is developed by the Member States or schools. Therefore, in future researches, it would be recommended to analyze the alignment of national and European anti-bullying policies. At the same time, it could be relevant to compare the European Union’s anti-bullying policies with other international and supranational organizations (e.g., UNESCO). Finally, it would be advisable to explore from a comparative approach how these European policies are developed at national level, given that this may differ significantly as the European Union does not have competences in the field of education.

6. Conclusions and Proposals for Improvement

In light of the considerations above, the following list of recommendations is put forward to enhance the efforts to combat school violence and bullying and strengthen the right to education within the European Union (UNESCO 2019; Dankmeijer 2020):

- Increasing the number of hard policies through directives (Neubauer 2023). On this way, nation-states could adapt anti-bullying policies to their national context.

- Strengthening anti-cyberbullying policies and regulating children’s access to social networks.

- Promoting the digital literacy of the educational community and students.

- Designing strategies to stimulate children’s participation in the design, implementation and evaluation of anti-cyberbullying policies.

- Putting forward concrete strategies and measures to foster community engagement against school violence.

- Adopting a comprehensive approach in anti-bullying policies, including aggressors and their families.

- Reinforcing teacher training on bullying and cyberbullying through ongoing training courses led by the European Union and the Member States.

- Consolidating the European values of equality, freedom, non-discrimination and peace through the educational systems.

- Promoting the exchange of good practices at different levels (school, local, regional, national, European, etc.)

- Designing evaluation and monitoring policies of anti-bullying policies based on the whole-school approach.

That said, it is necessary to stress the relevance of establishing an effective, binding, and sustainable evaluation system. In this way, the EU and its Member States will be able to develop resilient anti-bullying programs capable of responding to the changing social context, marked by the rapid and unstoppable development of artificial intelligence, which impact deeply in children and school’s dynamics.

In turn, these policies should be designed on the basis of empirical evidence. In conclusion, the European Union should lead the fight against bullying and cyberbullying among its Member States through policies that act as a guide and reference. However, it should be emphasized that imposed and overly rigid European policies can profoundly limit their implementation in national and school contexts. This problem, far from being solved, has opened new horizons that cannot wait to be addressed. For this reason, limiting the response to this phenomenon to the educational arena would be a mistake and requires coordinated and committed action by all stakeholders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.N. and A.G.-G.; methodology, A.N. and A.G.-G.; software, A.N.; validation, A.N.; formal analysis, A.N.; investigation, A.N. and A.G.-G.; resources, A.N.; data curation, A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, A.N. and A.G.-G.; writing—review and editing, A.N. and A.G.-G.; visualization, A.N. and A.G.-G.; supervision, A.N. and A.G.-G.; project administration, A.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research does not require Institutional Review Board Statement because it does not use personal data.

Informed Consent Statement

This research does not require informed consent because it does not use personal data.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the Data Availability Statement. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LGTBQI+ | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, and Asexual |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technology |

References

- Andrews, Naomi C. Z., Antonius H. N. Cillessen, Wendy Craig, Andrew V. Dane, and Anthony A. Volk. 2023. Bullying and the Abuse of Power. International Journal of Bullying Prevention 5: 261–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmeier, Omar, and Griselda Cardozo. 2024. Bullying y Ciberbullying en “post-pandemia”: Un estudio con adolescentes escolarizados de la ciudad de Córdoba. Revista De Psicología 20: 108–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bintz, William. 2023. Portrayal of Bullying in Selected Picture Books: A Content Analysis. Athens Journal of Education 10: 739–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgen, Nicolao Topstad, Dan Olweus, Lars Johannessen Kirkebøen, Kyrre Breivik, Mona Elin Solberg, Ivar Frønes, Donna Cross, and Oddbjørn Raaum. 2021. The Potential of Anti-Bullying Efforts to Prevent Academic Failure and Youth Crime: A Case Using the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (OBPP). Prevention Science 22: 1147–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos, Almudena, Beatriz Ortega-Ruipérez, and David Aparisi. 2022. Teachers’ Perspectives on Cyberbullying: A Cross-Cultural Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of the European Union. 1997. Council Conclusions of 22 September 1997 on Safety at School (OD, C303/3, 1997). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ES/TXT/?uri=CELEX:31997Y1004(02) (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Council of the European Union. 2011. Council Recommendation of 28 June 2011 on Policies to Reduce Early School Leaving (OD, C191/6, 2011). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=oj:JOC_2011_191_R_0001_01 (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Council of the European Union. 2021a. Council Recommendation of 12 March 2021 on Roma Equality, Inclusion and Participation (OD, C93/1, 2021). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ%3AJOC_2021_093_R_0001 (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Council of the European Union. 2021b. Council Recommendation of 29 November 2021 on Blended Learning Approaches for High-Quality and Inclusive Primary and Secondary Education (OD, C504/21, 2021). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32021H1214%2801%29 (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Council of the European Union. 2021c. Council Resolution on a Strategic Framework for European Cooperation in Education and Training Towards the European Education Area and Beyond (2021–2030) (OD, C66/1, 2021). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=oj:JOC_2021_066_R_0001 (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Council of the European Union. 2022. Council Recommendation of 28 November 2022 on Pathways to School Success and Replacing the Council Recommendation of 28 June 2011 on Policies to Reduce Early School Leaving (OD, C469/1, 2022). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=oj:JOC_2022_469_R_0001 (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Council of the European Union. 2024. Council Recommendation of 23 November 2023 on Improving the Provision of Digital Skills and Competences in Education and Training (OD, C1030, 2024). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/C/2024/1030/oj/eng (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1991. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review 43: 1241–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankmeijer, Peter. 2020. Antibullying Policies in Europe: A Review and Recommendations for European Quality Assessment of Policies to Prevent Bullying in Schools. GALE. Available online: https://www.gale.info/doc/project-abc/Review%20of%20Antibullying%20Quality%20Guidelines%20in%20Europe%20vs3.1.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- De la Plaza Olivares, Miguel, and Héctor González Ordi. 2019. El acoso escolar: Factores de riesgo, protección y consecuencias en víctimas y acosadores. Revista de Victimología 9: 99–131. Available online: https://www.huygens.es/journals/index.php/revista-de-victimologia/article/view/147/59 (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Del Rey, Rosario, Joaquín A. Mora-Merchán, José A. Casas, Rosario Ortega-Ruiz, and Paz Elipe. 2019. Programa ‘Asegúrate’: Efectos en ciberagresión y sus factores de riesgo. Comunicar 27: 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donogue, Christopher, and C. J. Pascoe. 2023. A sociology of bullying: Placing youth aggression in social context. Sociology Compass 17: e13071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2024. Commission Recommendation (EU) 2024/1238 of 23 April 2024 on Developing and Strengthening Integrated Child Protection Systems in the Best Interests of the Child (OD, L1238, 2024). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reco/2024/1238/oj/eng (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- European Parliament, and Council of the European Union. 2008. Decision No 1351/2008/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 Establishing a Multiannual Community Programme on Protecting Children Using the Internet and Other Communication Technologies (OD, L348/118, 2008). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dec/2008/1351/oj/eng (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- European Parliament, and Council of the European Union. 2021. Regulation (EU) 2021/692 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 April 2021 Establishing the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme and Repealing Regulation (EU) No 1381/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Council Regulation (EU) No 390/2014 (OD, L156/1, 2021). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2021/692 (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- European Parliament, Council of the European Union, and European Commission. 2006. Joint Statement by the Council and the Representatives of the Governments of the Member States Meeting Within the Council, the European Parliament and the Commission on European Union Development Policy: ‘The European Consensus’ (2006/C 46/01) (OD, C46/1, 2006). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=oj:JOC_2006_046_R_0001_01 (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. 2023. Fundamental Rights Report 2023. Available online: https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2023-fundamental-rights-report-2023-opinions_es_2.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Eurydice. 2022. Structural Indicators for Monitoring Education and Training Systems in Europe—2022. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/publications/structural-indicators-monitoring-education-and-training-systems-europe-2022?etrans=es (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Gaffney, Hannah, David P. Farrington, and María M. Ttofi. 2019. Examining the Effectiveness of School-Bullying Intervention Programs Globally: A Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Bullying Prevention 1: 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, Hannah, María M. Ttofi, and David P. Farrington. 2021. What Works in Anti-Bullying Programs? Analysis of Effective Intervention Components. Journal of School Psychology 85: 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimer, Maria, Elisabet Näsman, and Joakim Palme. 2017. Vulnerable children’s rights to participation, protection, and provision: The process of defining the problem in Swedish child and family welfare. Child & Family Social Work 23: 316–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hellström, Lisa, and Linda Beckman. 2020. Adolescents’ perception of gender differences in bullying. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 61: 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herkama, Sanna, and Christina Salmivalli. 2018. KiVa antibullying program. Reducing Cyberbullying in Schools: International Evidence-Based Best Practices. In Reducing Cyberbullying in Schools. Edited by Sanna Herkama and Christina Salmivalli. London: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Vargas, Felipe, María Aguilera Valdivia, René Valdés Morales, and María Hernández Yáñez. 2017. Migración y escuela: Análisis documental en torno a la incorporación de inmigrantes al sistema educativo chileno. Psicoperspectivas. Individuo y Sociedad 16: 105–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinheksel, A. J., Nicole Rockich-Winston, Huda Tawfik, and Tasha R. Wyatt. 2020. Demystifying Content Analysis. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 84: 127–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 2019. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Låftman, Sara B., Viveca Östberg, and Bitte Modin. 2017. School Leadership and Cyberbullying—A Multilevel Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14: 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesko, Nataliia, Iryna Khomyshyn, Uliana Parpan, Mariia Slyvka, and Maryana Tsvok. 2021. Legal principles of counteracting cyberbullying against children. Journal of Education Culture and Society 12: 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo Pontevedra, María del Carmen, and Elisardo Becoña Iglesias. 2022. Bullying y Ciberbullying. Madrid: Ediciones Pirámide. [Google Scholar]

- Matarranz, María. 2017. Análisis Supranacional de la Política Educativa de la Unión Europea 2000–2015. Hacia un Espacio Europeo de Educación. Doctoral dissertation, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10486/682755 (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Mayasari, Dian Ety, and Andreas L. Atjengbharata. 2024. Legal Protection for Child Victims of Bullying from the Perspective of Child Protection Law. Yuridika 39: 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, Philipp. 2014. Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution. Leibniz: GESIS—Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences. Available online: https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/bitstream/handle/document/39517/ssoar-2014-mayring-Qualitative_content_analysis_theoretical_foundation.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Menesini, Ersilia, and Christina Salmivalli. 2017. Bullying in schools: The state of knowledge and effective interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine 22 Suppl. 1: 240–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliaccio, Todd. 2022. Social Differentness and Bullying. A Discussion of Race, Class, and Income. In The Sociology of Bullying. Power, Status, and Aggression Among. Edited by Christopher Donogue. New York: New York University Press, pp. 166–87. [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer, Adrián. 2023. El derecho a la educación de la infancia inmigrante en la Unión Europea: Un análisis documental. Bordón. Revista De Pedagogía 75: 119–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, Adrián. 2025. La influencia de la política educativa de la Unión Europea en los Estados miembros: El caso del derecho a la educación de la infancia inmigrada. Revista Española de Educación Comparada 46: 386–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo, Lojo A., Brett Shelton, and Katie Bubak-Azevedo. 2021. Education Professionals’ Knowledge and Needs Regarding Bullying. EDU REVIEW. International Education and Learning Review 8: 265–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paljakka, Antonia. 2024. Teachers’ Awareness and Sensitivity to a Bullying Incident: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Bullying Prevention 6: 322–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renz, Susan M., Jane M. Carrington, and Terry A. Badger. 2018. Two Strategies for Qualitative Content Analysis: An Intramethod Approach to Triangulation. Qualitative Health Research 28: 824–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romera, Eva M., Rocío Luque-González, Cristina M. García-Fernández, and Rosario Ortega-Ruiz. 2022. Social Competence and Bullying: The Role of Age and Sex. Educación XX1 25: 309–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio Hernández, Francisco José, Adoración Díaz López, and Fuensanta Cerezo Ramírez. 2019. Bullying y cyberbullying: La respuesta de las comunidades autónomas. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado 22: 145–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Casares, Mónica, and Tara M. Collins. 2016. Children’s rights to participation and protection in international development and humanitarian interventions: Nurturing a dialogue. The International Journal of Human Rights 21: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Peter K., Keumjoo Kwak, and Yuichi Toda. 2016. School Bullying in Different Cultures: Eastern and Western Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stemler, Steven E. 2015. Content analysis. In Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Interdisciplinary, Searchable, and Linkable Resource. Edited by Scott Robert A. and M. C. Buchman. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swearer, Susan M., James Peugh, Dorothy L. Espelage, Amanda B. Siebecker, Whitney L. Kignsbury, and Katherine S. Bevins. 2006. A Social-Ecological Model for Bullying Prevention and Intervention in Early Adolescence: An Exploratory Examination. In The Handbook of School Violence and School Safety: From Research to Practice. Edited by Shane R. Jimerson and Michael J. Furlong. Mahwah: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2019. Behind the Numbers: Ending School Violence and Bullying. París: UNESCO. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child. 2021. General Comment No. 25 on Children’s Rights in Relation to the Digital Environment. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/general-comments-and-recommendations/general-comment-no-25-2021-childrens-rights-relation (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Vaill, Zoe, Marilyn Campbell, and Chrystal Whiteford. 2020. Analysing the Quality of Australian Universities’ Student Anti-Bullying Policies. Higher Education Research & Development 39: 1262–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williford, Anne, L. Christian Elledge, Aaron J. Boulton, Kathryn J. DePaolis, Todd D. Little, and Christina Salmivalli. 2013. Effects of the KiVa Antibullying Program on Cyberbullying and Cybervictimization Frequency Among Finnish Youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 42: 820–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2021. Global Status Report on Violence Against Children 2020: Executive Summary. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/publications/i/item/9789240006379 (accessed on 21 January 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).