Effects of Child Development Accounts on Adolescent Behavior Problems: Evidence from a Longitudinal, Randomized Policy Experiment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

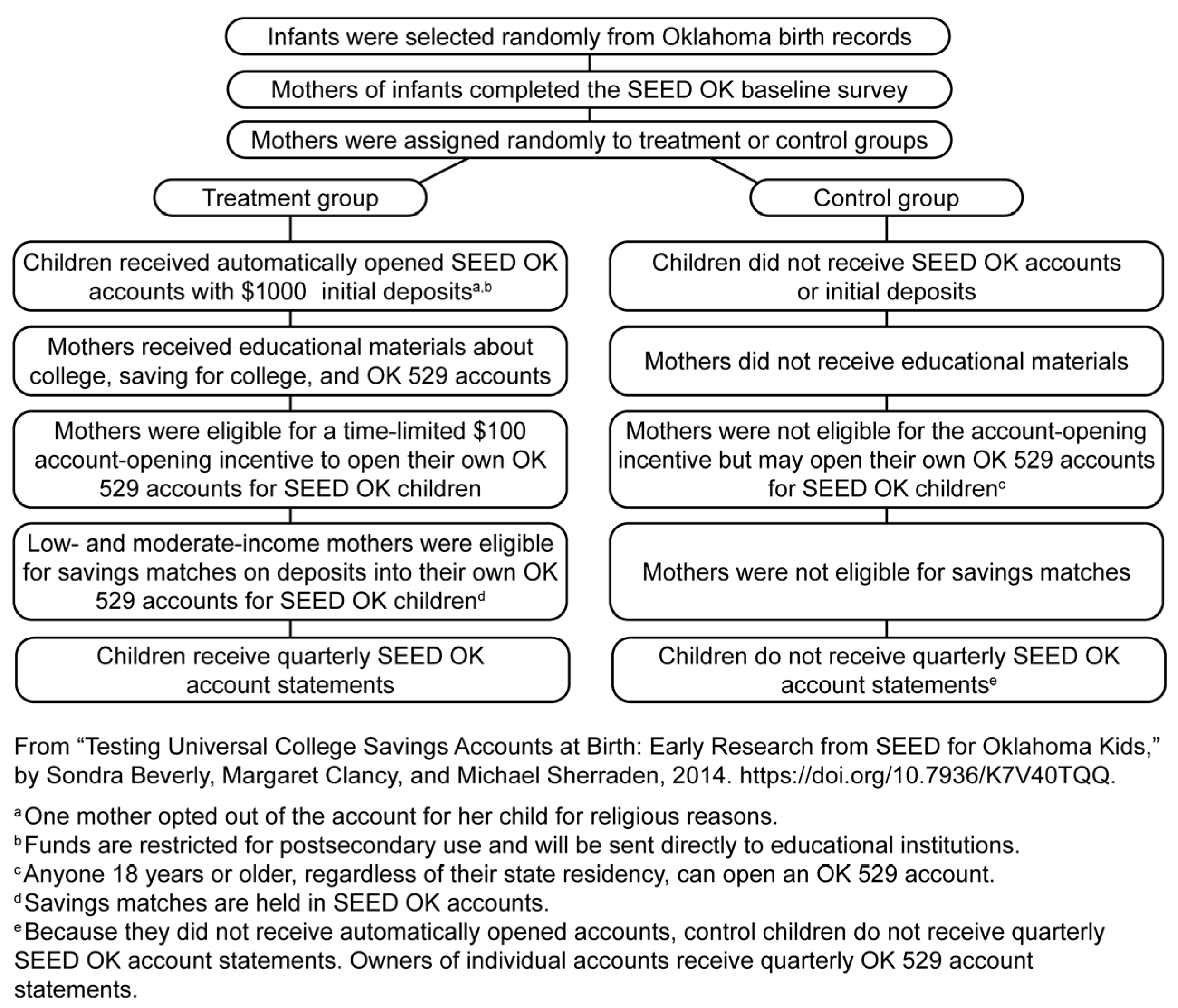

2.1. The SEED for Oklahoma Kids Experiment

2.2. Data and Sample

2.3. Outcome and Focal Independent Variables

- “The child has sudden changes in mood or feeling.”

- “The child feels or complains that no one loves him/her.”

- “The child is too fearful or anxious.”

- “The child is unhappy, sad, or depressed.”

- “The child feels worthless or inferior.”

- “The child is disobedient at school.”

- “The child has trouble getting along with other children.”

- “The child is disobedient at home.”

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Descriptions

3.2. Measures of Children’s Behavior Problems

3.3. CDA Effects on Adolescents’ Behavior Problems

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BPI | Behavior Problems Index |

| CDA | Child Development Account |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| OK 529 | Oklahoma 529 College Savings Plan |

| SEED OK | SEED for Oklahoma Kids |

| SES | Socioeconomic status |

| SNAP | Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| TANF | Temporary Assistance for Needy Families |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index |

References

- Adams, Gerald R. 2005. Adolescent development. In Handbook of Adolescent Behavioral Problems: Evidence-Based Approaches to Prevention and Treatment. Edited by Thomas P. Gullotta and Gerald R. Adams. New York: Springer Science & Business Media, pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnafors, Sara, Mimmi Barmark, and Gunilla Sydsjö. 2021. Mental health and academic performance: A study on selection and causation effects from childhood to early adulthood. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 56: 857–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansong, David, Moses Okumu, Thabani Nyoni, Jamal Appiah-Kubi, Emmanuel Owusu Amoako, Isaac Koomson, and Jamie Conklin. 2024. The effectiveness of financial capability and asset building interventions in improving youth’s educational well-being: A systematic review. Adolescent Research Review 9: 647–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcaya, Mariana C., Alyssa L. Arcaya, and S. V. (Subu) Subramanian. 2016. Inequalities in health: Definitions, concepts, and theories. Global Health Action 9: 293–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Gary S. 1981. A Treatise on the Family. Harvard: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2024. Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report: 2013–2023; Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/yrbs/dstr/pdf/YRBS-2023-Data-Summary-Trend-Report.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Christiansen, Julie, Pamela Qualter, Karina Friis, Susanne S. Pedersen, Rikke Lund, Christina M. Andersen, Maj Bekker-Jeppesen, and Mathias Lasgaard. 2021. Associations of loneliness and social isolation with physical and mental health among adolescents and young adults. Perspectives in Public Health 141: 226–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curley, Jami, Fred Ssewamala, and Chang-Keun Han. 2010. Assets and educational outcomes: Child Development Accounts (CDAs) for orphaned children in Uganda. Children and Youth Services Review 32: 1585–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson-Davis, Christina, and Heather D. Hill. 2021. Childhood wealth inequality in the United States: Implications for social stratification and well-being. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 7: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grinstein-Weiss, Michal, Trina R. Williams Shanks, and Sondra G. Beverly. 2014. Family assets and child outcomes: Evidence and directions. The Future of Children 24: 147–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guadagnoli, Edward, and Wayne F. Velicer. 1988. Relation of sample size to the stability of component patterns. Psychological Bulletin 103: 265–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Jin, Michael Sherraden, Kim Youngmi, and Margaret Clancy. 2014. Effects of Child Development Accounts on early social-emotional development: An experimental test. JAMA Pediatrics 168: 265–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Jin, Michael Sherraden, Margaret M. Clancy, Sondra G. Beverly, Trina R. Shanks, and Youngmi Kim. 2021. Asset building and child development: A policy model for inclusive Child Development Accounts. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 7: 176–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim-Cohen, Julia, Avshalom Caspi, Terrie E. Moffitt, HonaLee Harrington, Barry J. Milne, and Richie Poulton. 2003. Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: Developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry 60: 709–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerman, Robert, and Signe-Mary McKernan. 2008. Benefits and consequences of holding assets. In Asset Building and Low-Income Families. Edited by Signe-Mary McKernan and Michael Sherraden. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press, pp. 175–206. [Google Scholar]

- Low, Natalie, and Nina S. Mounts. 2022. Economic stress, parenting, and adolescents’ adjustment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Family Relations 71: 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, Ellen L., Bryan B. Rhodes, and Scott Scheffler. 2008. SEED for Oklahoma Kids: Baseline Analysis. Research Triangle Park: RTI International. [Google Scholar]

- McGue, Matt, and William G. Iacono. 2005. The association of early adolescent problem behavior with adult psychopathology. American Journal of Psychiatry 162: 1118–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, James L., and Nicholas Zill. 1986. Marital disruption, parent-child relationships, and behavior problems in children. Journal of Marriage and Family 48: 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peverill, Matthew, Melanie A. Dirks, Tomás Narvaja, Kate L. Herts, Jonathan S. Comer, and Katie A. McLaughlin. 2021. Socioeconomic status and child psychopathology in the United States: A meta-analysis of population-based studies. Clinical Psychology Review 83: 101933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reef, Joni, Sophia Diamantopoulou, Inge Van Meurs, Frank Verhulst, and Jan Van Der Ende. 2009. Child to adult continuities of psychopathology: A 24-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 120: 230–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherraden, M. 1991. Assets and the Poor: A New American Welfare Policy. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe. [Google Scholar]

- Sherraden, Michael, Margaret M. Clancy, and Sondra G. Beverly. 2018. Taking Child Development Accounts to Scale: Ten Key Policy Design Elements. (CSD Policy Brief No. 18-08). St. Louis: Washington University, Center for Social Development. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troller-Renfree, Sonya V., Molly A. Costanzo, Greg J. Duncan, Katherine Magnuson, Lisa A. Gennetian, Hirokazu Yoshikawa, Sarah Halpern-Meekin, Nathan A. Fox, and Kimberly G. Noble. 2022. The Impact of a Poverty Reduction Intervention on Infant Brain Activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 119: e2115649119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Medical Association. 2022. WMA Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Available online: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Yeung, Wen-Jun, Miriam R. Linver, and Jeanne Brooks–Gunn. 2002. How money matters for young children’s development: Parental investment and family processes. Child Development 73: 1861–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Li, and Michael Sherraden. 2022. Child Development Accounts Reach Over 15 Million Children Globally. (CSD Policy Brief No. 22-22). St. Louis: Washington University, Center for Social Development. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Control (n = 328) | Treatment (n = 348) | Possible Responses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child | |||

| Male (%) | 50.02 | 54.32 | 1 = Male 0 = Female |

| Race (%) | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 69.45 | 70.29 | 1 = Non-Hispanic White 2 = Non-Hispanic African Americans 3 = Non-Hispanic American Indian 4 = Non-Hispanic Asian American and Pacific Islander 5 = Hispanic |

| Non-Hispanic African American | 7.26 | 8.19 | |

| Non-Hispanic American Indian | 8.28 | 9.45 | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian American and Pacific Islander | 1.98 | 2.05 | |

| Hispanic | 13.04 | 10.02 | |

| Child’s age, M (SD), by year | 12.48 (0.19) | 12.48 (0.18) | |

| Mother | |||

| Age, M (SD), by year | 26.38 (5.64) | 26.67 (5.50) | |

| Education (%) | |||

| Below high school | 17.15 | 14.75 | 1 = Below high school diploma 2 = High school diploma or general equivalency diploma 3 = Some college 4 = 4-year college or above |

| High school | 32.09 | 28.07 | |

| Some college | 21.64 | 25.77 | |

| 4-year college or above | 28.22 | 31.42 | |

| Health status, M (SD) | 4.16 (0.91) | 4.20 (0.88) | 1 (poor)–5 (excellent) |

| Marital status (% married) | 67.58 | 67.53 | 1 = Married 2 = Other |

| Employment status (% working) | 56.29 | 56.60 | 1 = Working 0 = Not working |

| Household | |||

| Household size, M (SD) | 2.97 (1.10) | 3.20 (1.31) | |

| Save monthly (% yes) | 70.49 | 64.56 | |

| Parenting attitude index, M (SD) | 11.02 (1.38) | 11.12 (1.40) | 6–14 (higher score indicates positive attitudes) |

| Homeownership (% yes) | 54.77 | 54.50 | 1 = Yes 0 = No |

| TANF participation (% yes) | 7.35 | 7.84 | 1 = Yes 0 = No |

| SNAP participation (% yes) | 32.33 | 30.18 | 1 = Yes 0 = No |

| Income-to-needs ratio, M (SD) | 241.54 (262.31) | 233.86 (239.04) | |

| English as primary language at home (% yes) * | 90.90 | 95.21 | 1 = Yes 0 = No |

| Geographic areas (%) * | |||

| Metropolitan area | 62.09 | 71.69 | 1 = Metropolitan area 2 = Micropolitan area 3 = Other |

| Micropolitan area | 22.75 | 16.84 | |

| Other | 15.16 | 11.47 |

| Measure | Treatment (n = 348) | Control (n = 328) | Treatment-Control Difference | CFA Loading on 2 Latent Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | ||||

| 1. Sudden mood changes | 2.46 (0.61) | 2.42 (0.61) | +0.04 | 0.59 (0.06) *** |

| 2. Complaining no love | 2.89 (0.37) | 2.83 (0.43) | +0.06 * | 0.87 (0.05) *** |

| 3. Too fearful | 2.67 (0.57) | 2.57 (0.58) | +0.10 ** | 0.44 (0.07) *** |

| 4. Feel unhappy or depressed | 2.72 (0.52) | 2.71 (0.46) | +0.01 | 0.76 (0.06) *** |

| 5. Feel worthless | 2.82 (0.43) | 2.75 (0.45) | +0.07 * | 0.77 (0.05) *** |

| Disobedience | ||||

| 6. Disobedient at school | 2.81 (0.48) | 2.82 (0.44) | −0.01 | 0.65 (0.08) *** |

| 7. Not getting along with others | 2.81 (0.45) | 2.80 (0.42) | +0.01 | 0.79 (0.07) *** |

| 8. Disobedient at home | 2.54 (0.60) | 2.59 (0.52) | −0.05 | 0.67 (0.08) *** |

| Sum score after dichotomization (0–8) | 5.98 (1.95) | 5.74 (1.85) | 0.24 * | |

| CFI | 0.99 | |||

| TFI | 0.98 | |||

| RMSEA (90% CI) | 0.03 (0.00–0.04) | |||

| CDA Effect | Pre-COVID Sample (n = 676) | Full Sample (N = 1712) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum Score | Anxiety | Disobedience | Sum Score | Anxiety | Disobedience | |

| Treatment group (yes) | 0.24 (0.07) * | 0.20 (0.04) ** | 0.03 (0.39) | 0.04 (0.39) | 0.05 (0.25) | −0.02 (0.38) |

| R2 | 0.07 | 0.07 | ||||

| CFI | 0.97 | 0.96 | ||||

| TFI | 0.95 | 0.94 | ||||

| RMSEA (90% CI) | 0.02 (0.01–0.03) | 0.02 (0.01–0.03) | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zeng, Y.; Huang, J.; Sherraden, M. Effects of Child Development Accounts on Adolescent Behavior Problems: Evidence from a Longitudinal, Randomized Policy Experiment. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080495

Zeng Y, Huang J, Sherraden M. Effects of Child Development Accounts on Adolescent Behavior Problems: Evidence from a Longitudinal, Randomized Policy Experiment. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(8):495. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080495

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Yingying, Jin Huang, and Michael Sherraden. 2025. "Effects of Child Development Accounts on Adolescent Behavior Problems: Evidence from a Longitudinal, Randomized Policy Experiment" Social Sciences 14, no. 8: 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080495

APA StyleZeng, Y., Huang, J., & Sherraden, M. (2025). Effects of Child Development Accounts on Adolescent Behavior Problems: Evidence from a Longitudinal, Randomized Policy Experiment. Social Sciences, 14(8), 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080495