Abstract

This study interrogates the semiotic destabilization of rural cultural symbols in China’s burgeoning short video sphere, with particular focus on the discursive reconstruction of “tǔ wèi” labeling. This paper, through semantic tracing and content analysis, combined with empirical data from over 130,000 “tǔ wèi” videos on Douyin (Tik Tok), categorizes the “tǔ wèi” content into two major styles: the novelty-hunting and ugliness-seeking style and the rural original ecological style. It also compares the differences in popularity, quality, and value orientation between the two. The research finds that the semantic segmentation of the “tǔ wèi” label is rooted in clash of civilizations and the urban–rural dichotomy, as well as the promotion of the traffic logic and symbol abuse of short video platforms. This segmentation has exacerbated the stigmatization of Chinese farming culture and weakened cultural confidence. It is suggested that efforts should be made from three aspects: deep exploration of indigenous “tǔ” cultural resources, optimization of algorithm recommendation mechanisms, and reconstruction of discourse contexts, to promote the semantic return of the “tǔ wèi” label and consolidate cultural subjectivity.

1. Introduction

At the symposium on the development of cultural heritage in June 2023, President Xi pointed out that “cultural confidence comes from our cultural subjectivity” (Xi 2023, pp. 4–7), and in the context of globalization, the construction of cultural subjectivity faces the challenge of the symbolic game. In the current cultural field, the cognitive framework of “Western-centrism” still profoundly affects the cultural value judgement, causing the dilemma of innovative development of Chinese civilizations. In this paper, we focus on the semantic transmutation of the symbol of “tǔ”: as the core symbol of farming civilizations, “tǔ” has been heterogeneously encoded by short video platforms in the digital media era, resulting in a rupture between the symbols and referents of “tǔ wèi”, leading to a deviation in the public’s perception of the rural conditions and farming culture that the “tǔ wèi” label represents. This break not only dissolves the continuity of cultural memory but also reflects the deep crisis of cultural identity.

2. Tracing Back to “Tǔ” and “Tǔ Wèi”: Semantic Flux and Conceptual Definition

2.1. The Original Meaning of “Tǔ” and Its Recent Semantic Alienation

As the archetypal symbol of the Chinese character system, “tǔ” is a microcosmic mirror of the spiritual map of Chinese civilization through the evolution of its referent and denotation over time. The oracle bone character “tǔ” has “—” (horizontal) as the ground plane, and “丨” (radical in Chinese characters) indicates the breaking of the ground by plants, and Xu Shen’s Shuowen Jiezi (“Explaining and Analysing Characters”) interpreted “tǔ” as “the ground that spits out living things” (Xu 2015, p. 427), and “tǔ” in the structure of “bisecting the vertical and horizontal” symbolises “under the earth” and “in the earth”, which reveals the cultural gene of Chinese civilization of “being attached to one’s native land and unwilling to leave it”. The Chinese civilization’s cultural genes of “settling down and relocating” are revealed in its structure.

Fei Xiaotong’s “vernacularity” revealed in “Native China” is a sociological metaphor for the symbol of “tǔ”. Through the theory of “differential order pattern”, he pointed out that traditional societies build up an ethical community “born and raised in the land” with the land as a bond (Fei [1947] 2012, p. 107). This phenomenon of “land-bundling” has produced cultural symbols such as “hometown” and “hometown party” in the language system, making “tǔ” a meta-narrative for maintaining cultural identity.

However, since the middle of the 19th century, with the rise of industrial civilizations, “tǔ” symbols suffered a fundamental crisis. The journalist of the Shunpao (the Shanghai newspaper) lamented that the craftsmanship of various countries was becoming more and more sophisticated, but the local products were “stupid against wise, clumsy against clever” and were bound to be sidelined, “this is the axiom of the evolution of the world, and I do not see that it can be escaped” (Shun Pao 1905). The word “tǔ” was gradually given negative connotations such as “backwardness” and “ignorance”.

The urbanisation process after the reform and opening up has intensified the semantic fragmentation of “tǔ”. Bourdieu’s theory of “cultural capital” shows its explanatory power here: when urban elites monopolise the power of symbolic interpretation through the education system, “tǔ” is constructed as a symbolic mark of lack of cultural capital (Bourdieu 2015, p. 110). Since the reform and opening up, the semantic field of “tǔ” has given rise to stigmatised variants such as “tǔ wèi” and “tǔ biē”. This alienation is even more pronounced at the spatial–political level, as city administrators physically expel the symbol of “tǔ” from the modernisation landscape through discursive practices such as the “transformation of urban villages”. Lefebvre’s theory of spatial production suggests that this spatial reconfiguration is essentially a projection of power relations in the symbolic dimension (Lefebvre 2022, p. 102).

The evolution of media technology has given rise to new alienation mechanisms. Short video platforms have alienated farming culture symbols into objects of spectacle consumption through the production of “tǔ wèi” content. Statistics from the New List show that video content under the label of “tǔ wèi” on the Tik Tok platform has received 170 million likes in half a year (New List Data 2024), but most of it is produced in a “cheap and playful” way, using big data recommendations to gain traffic and participate in the construction of stereotypical images of the countryside (Liu and Zhu 2022).

This “new cultural movement” in the digital age has ostensibly given vitality to the dissemination of “tǔ” symbols, but in fact, it follows the logic of “symbolic consumption” revealed by Baudrillard—when cultural memories are transformed into quantifiable traffic data, the authenticity of “tǔ” has already disappeared in the hyper-real mimicry (Baudrillard 2000, p. 76). This postmodern dilemma suggests that semantic alienation is not only a linguistic phenomenon but also a symptomatic manifestation of the crisis of cultural subjectivity during the transition of civilizations.

2.2. Definition and Differentiation of “Tǔ Wèi Culture”

The symbolic generation and fragmentation of “tǔ wèi culture” is essentially a micro-mirror of the redistribution of cultural capital in the digital age (Chen 2019, p. 75). From the perspective of linguistic genesis, the semantic activation of “tǔ wèi” as an energetic symbol in 2016 actually continues the pejorative trajectory of the “tǔ” word family in modern Chinese.

Chen’s (2019) semantic network analysis reveals that in the early use of the word in the KuaiShou and Weibo domains, it formed an intertextual relationship with subcultural symbols such as “shouting vocal” and “social rocking”, and its inferiority was constantly reinforced. This kind of stigmatisation confirms the mechanism of “downgrading” in Bakhtin’s theory of carnival—urban youths complete their identity separation by parodying rural culture.

However, the algorithmic empowerment of short video platforms breaks this unidirectional symbolic violence and brings “tǔ wèi” into a complex field of meaning game.

Under the operating logic of platform capitalism, the symbol of “tǔ wèi” has undergone a double alienation: one is the alienation of landscape.

In order to comply with the “5-s burst” rule of short videos, the “tǔ wèi” videos of the novelty-hunting and ugliness-seeking style are made through exaggerated facial expressions (such as the twisted interpretation of “Teacher Guo”), surreal plots (such as the absurd narrative of “Brother Giao”), and magical music (such as the song “tǔ wè disco”), these videos transform agricultural and cultural symbols into a source of sensory stimulation. This mode of production alludes to Debord’s theory of the landscape society—when cultural memory is cut into reproducible audiovisual fragments, the chain of symbolic referent and denotation breaks down (Debord 2017, p. 5).

The second is the incorporation of the aestheticisation. Take Li Ziqi as an example; her video constructs a “new idyllic pastoral” that meets the imagination of the urban middle class through cinematic camera work and elaborate costumes. This kind of cultural translation is, in fact, a contemporary interpretation of Bourdieu’s strategy of “distinction”, in which “tǔ wèi” is sublimated into cultural capital, completing the transformation of vernacular symbols by removing them from the rural symbols (Bourdieu 2015, p. 10).

The deep-rooted contradiction between the two styles of “tǔ wèi” texts maps out the cultural cognitive split in postmodern society. From the perspective of the political economy of communication, the algorithmic recommendation mechanism has exacerbated this division: the “tǔ wèi” videos of the novelty-hunting and ugliness-seeking style have emerged and become popular among the youth in the townships, and their interactive behaviours tend to be playful (e.g., the bullet chat carnival of “the extreme tǔ wèi is trendy”), which do not fit into the vision of the urban middle class, whereas the aestheticised “tǔ wèi” content is more oriented towards the urban residents (in fact, it has been received by all sectors of the society (Han 2020, p. 3770)), and its cultural consumption is more inclined to aesthetic nostalgia (e.g., “Li Ziqi Awakens Nostalgia” hot comments).

The essence of this user stratification is the projection of the digital divide in the cultural dimension—when platforms integrate users into different “information cocoons” through LBS positioning and interest tags, “tǔ wèi” symbols are reduced to ideological tools for class identity.

What is more noteworthy is the phenomenon of hedging symbolic value systems. In the semiotic matrix, the hunt for “tǔ wèi” videos of the novelty-hunting and ugliness-seeking style follows the coding logic of “anti-elite—mass revelry”, and most of its videos contain teasing of urban civilization (e.g., the deconstruction of inspirational discourse in “Orly Give”); while the “tǔ wèi” videos of the aestheticised style adopts the narrative strategy of “neo-traditionalism”, constructing an imaginary space for urban–rural reconciliation through the use of temporal and spatial compression (e.g., the juxtaposition of 1970s nostalgia elements and smartphones in Student Zhang’s video). This value split reached its peak in the “tǔ wèi culture debate” in 2021: while Zhihu users criticised the hunting of “tǔ wèi” with the “aesthetic poverty theory”, B-station launched the “tǔ wèi” renaissance movement, trying to reconstruct cultural identity through symbolic collage (e.g., “Coyote Disco” combines northeastern dialect and hip-hop elements). This kind of confrontation confirms the negotiated interpretation in Hall’s encoding/decoding theory—when different groups compete for the right to interpret the symbols of “tǔ wèi”, they are actually reconstructing the boundaries of cultural power (Hall 1980, pp. 128–38).

The current semantic fragmentation of “tǔ wèi” culture is essentially a digital manifestation of the cultural contradictions between urban and rural areas in the process of modernisation. When Tik Tok’s algorithm recommends the juxtaposition of “Village Stage” and “Oriental Aesthetics”, the platform seems to have achieved a local presentation of culture, but, in fact, it has completed the reclassification of vernacular symbols through the distribution of traffic. This dilemma of cultural differentiation reminds us that when discussing cultural identity in the digital age, we must penetrate the symbolic appearance and deeply analyse the capital logic and power relationship network behind it.

“tǔ wèi” emerged as an Internet popular discourse in 2016, initially referring to “tacky” and “low-end” subcultural content (Chen 2019, pp. 75–76). Under the promotion of short video platforms, the label of “tǔ wèi” is divided into two categories: one is the novelty-hunting and ugliness-seeking style, with exaggerated performances and brainwashing music catering to the sensory stimulation of users; and the other is the rural original ecological style, represented by Li Ziqi and Student Zhang presenting the simple farming life (Wang 2021). The two styles of content share the symbol of “tǔ wèi” but point to very different cultural values, constituting the core contradiction of semantic fragmentation.

3. Characteristics of the Semantic Fragmentation of the “Tǔ Wèi” Label: Content Patterns and Communication Imbalance

In order to better demonstrate the semantic fragmentation of the “tǔ wèi” label, that is, the two styles of short videos both with the “tǔ wèi” label—the novelty-hunting and ugliness-seeking style and the rural original ecological style—have completely different value orientations, and further explore the impact of the “tǔ wèi” label on cultural subjectivity and cultural confidence, this paper compiles and codes the short videos on the Douyin (Tik Tok) platform with “tǔ wèi” as the keyword, and the data show that the proportion of the novelty-hunting and ugliness-seeking style videos is more than 90%, and the total number of likes reaches 166 million, which is far more than the 6.51 million of the rural original ecological style (New List Data 2024). The former relies on algorithmic recommendations to form a “viral spread”, while the latter is caught in a traffic predicament. In terms of value orientation, the clash between the novelty-hunting and ugliness-seeking style that reinforces the pejorative label of “tǔ” and the positive connotation of “tǔ” that rural originality tries to reconstruct has exacerbated the semantic fragmentation.

3.1. Typological Analysis of “Tǔ Wèi” Videos

Based on Lasswell’s communication function theory, this study uses frame analysis to dismantle the coded videos and categorise them into the following four types and describes the characteristics of each type of video in terms of three dimensions: video language, video rhythm, and video content.

- Display function reconstruction: the dilemma of dispelling idyllic wonders and farming culture.

The rural original ecological style videos, such as Li Ziqi’s and Student Zhang’s works, use slow-paced narratives and de-technological filming to construct “mimetic of rurality”, delivering idyllic virtual experiences of the countryside (Jiao et al. 2022, pp. 279–94) and attempting to complete a bicultural practice:

- ➀

- Symbol reconstruction: Through the clustering of farming symbols such as wood-fired stoves, handmade bamboo weaving, and old-fashioned food, the rural space is constructed as an “antidote” to the anxiety of modernity;

- ➁

- Dissemination paradox: the low compatibility of algorithmic traffic pools for slow-paced content forces creators to introduce accelerated montage (e.g., Student Zhang switching 186 shots in 7 min) to adapt to the platform rules, resulting in the “original” narrative falling into the technical dilemma of self-defeating.

- 2.

- Entertainment function dominance: the algorithmic collusion of ritualised performance and sensory stimulation.

The music and dance genre represented by “social rocking” has constructed a set of anti-elitist subcultural rituals through highly repetitive movements (such as crotch swinging and mechanised swaying) and symbolic body performances (such as Korean suits, gommino, and other “tǔ” costumes). The logic of its dissemination presents three features:

- ➀

- Text production: Relying on brainwashing DJ music (with an average tempo of 120 BPM or more) and social quotations (e.g., “put on your socks before you put on your shoes, be a grandson before you become a grandfather”), traditional discourse authority is deconstructed through verbal violence and physical humor;

- ➁

- Algorithm boost: 20 s of ultra-short video length to adapt to the platform’s “golden 5s” retention mechanism, forming the closed loop of dissemination: sensory stimulation—instant feedback—traffic fission;

- ➂

- Cultural Criticism: This kind of content is essentially a strategy for rural youth to compete for discourse through self-stigmatising performances under the urban–rural stratification, but it is alienated in the logic of algorithms and turned into entertainment and consumer products for “digital labourers”.

- 3.

- Alienation of communicative functions: modal orgy and the variation of linguistic violence in a variant of communication

The “tǔ wèi” discourse and meme type of works are essentially the mutated forms of internet modalities (Nicola 2017), whose dissemination presents a double contradiction:

- ➀

- Language layer: the interactive ritual is completed by semantic puns such as “Lack of you”, but it evolves into linguistic inflation in viral transmission;

- ➁

- Power layer: grassroots groups use “tǔ wèi” discourse to build a resistant identity (e.g., “You can be as crazy as you want, I’ll be my king”), but the platform algorithm’s preference for controversial content reinforces cultural distinction, turning “tǔ wèi” into a cultural other under the gaze of the urban elite.

- 4.

- Propaganda function game: the symbolic war between commercial adoption and public discourse

The appropriation of “tǔ wèi” elements by official and commercial organisations (e.g., the Guangxi firefighting “enrollment advertisement by flowers shaking hands”) reflects the paradoxical nature of postmodern communication: at the strategic level, it adopts the reverse coding strategy of “the extreme tǔ wèi is trendy”, and attempts to achieve a youthful translation of public discourse through the collage of social rocking movements and policy slogans (e.g., “vaccine protects the body, evil poison retreats”).

To summarise, around the three levels of video language, video rhythm, and video content, their common characteristics can be extracted, and based on this, the four major types of video can be summarised into two major video styles, namely, the novelty-hunting and ugliness-seeking style and the rural original ecological style, which are collated into the following Table 1:

Table 1.

Content pattern differentiation under the label “Tǔ Wèi”.

The table shows that in the current dissemination and processing of “tǔ wèi” culture, two styles of video patterns share the “tǔ wèi” label as a linguistic signifier attribute two styles of video samples share the “backwardness”. But in fact, the “backwardness” attribute of the “tǔ wèi” label has been over-generalised and even misinterpreted. It originates from and points to the low material living conditions in rural areas within a certain period of time and is not equivalent to the lack of spiritual civilizations, let alone backwardness or even vulgarity of culture. However, in the actual use of the word, the “backwardness” attribute of the “tǔ wèi” label has been misinterpreted as an inferior feature of culture, and has a cultural orientation of the novelty-hunting and ugliness-seeking, with a distinctly pejorative emotional colouring, which is mixed with the original cultural orientation of a positive emotional colouring and creates a strong conflict, resulting in the problem of semantic fragmentation of the “tǔ wèi” label.

3.2. Dichotomy Between Heat and Value Orientation

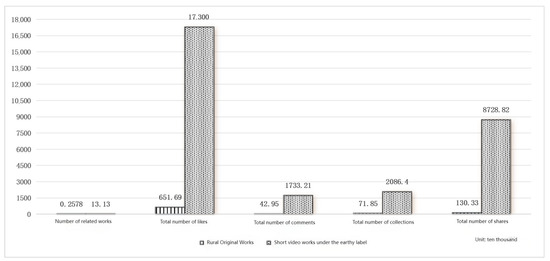

At present, there is a serious imbalance between the two major video styles in terms of heat in communication, with traffic tilting heavily towards the novelty-hunting and ugliness-seeking style. Taking the Tik Tok platform as an example, with the help of the New List data platform, searching with the keyword “tǔ wèi” and taking nearly half a year as the deadline, from 30 May 2024 to 25 November 2024, there were about 131,300 related works, with a total of about 173 million likes, 17,332,100 comments, 20,864,000 favourites(/collections), and 87,288,200 shares.

On the basis of “tǔ wèi” as the keyword, “rural life” was selected as the secondary screening condition to know the traffic heat of the rural original ecological style video under the label of “tǔ wèi”, and it was found that both the number of works and the traffic heat had dropped significantly. There were about 2578 related works, with a total of about 6,516,900 likes, 429,500 comments, 718,500 favourites(/collections), and 1,303,300 shares (New List Data 2024), and the above data are plotted as a chart in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Comparison of the popularity of videos labelled as “tǔ wèi” and the rural original ecological style videos on the Tik Tok platform in the past 6 months.

Comparison found that among the video styles under the label of “tǔ wèi” on short video platforms, rural original ecological style videos are at a disadvantage in terms of both quantity and heat. It should be noted that due to the shortcomings of the screening system itself, a closer examination of the video content will reveal that some works with the background of rural life, the quality and value orientation of which are actually attributed to the novelty-hunting and ugliness-seeking style, have also been included in the category of “Rural Life”, which means that the number of works and the heat of rural original ecological style works should also be lower than that of the statistical data.

In contrast, works attributed to the novelty-hunting and ugliness-seeking style, by their brainwashing characteristics, dominate the Internet through “viral dissemination”, where the masses are not only the viewers of the video content, but also the forwarders and creators of the video—they not only share the video with family and friends, but also imitate and film the same style of video—thus creating a situation of high number of works and high sharing. These works use the power of the masses to carry the message across the entire platform in an interpersonal sweeping mode (Liu 2007, pp. 54–55).

Further, in terms of the analysis of content quality and value orientation, this study takes the comprehensive theory of multimodal discourse analysis provided by scholar Zhang Delu as a framework (Zhang 2009, pp. 24–30) and analyses the actual content of the integrated video as follows:

The works of the novelty-hunting and ugliness-seeking style, including music and dance type, text and image type, and publicity advertising type, show significant vulgarisation, planarization, and even vulgarisation in terms of the quality of content.

The specific modes of expression are:

- ➀

- Language expression: the language of the works is generally rough and awkward, even with indecent and vulgar tendencies, lacking cultural depth and artistic beauty.

- ➁

- Rhythm and background music: the rhythm of the video is too fast, the background music melody is monotonous and repetitive, and the lyrics are empty, lacking in ideology and artistry.

- ➂

- Repetitive content: the content of social quotations, “tǔ wèi” lover’s prattle and dance movements, is highly repetitive and lacks innovation, showing obvious set characteristics.

- ➃

- Logical rupture between modes: at the early stage of the novelty-hunting and ugliness-seeking videos, there is a lack of correlation between the multimodal elements, which is in line with the non-complementary relationship of multimodal discourse, such as “redundancy” (repetition of modes with no reinforcing effect) or “offsetting” (modal conflict leading to meaning dissolution).

The long-term dissemination process of video makes users form a conditioned reflex cognition of specific modal combinations, which are recommended by algorithms and accepted by users through inertia, forming symbolic rituals (e.g., the bullet chat carnival of “the extreme tǔ wèi is trendy”), which belongs to the alienated form of the relationship of “union” in the framework. This is a form of alienation of the “union” relationship in the framework of “pseudo-complementarity”, but it does not change the nature of the inter-modal logical rupture. For example, the “Subject Three” dance was massively popular in 2021, and its background music, “A Smile at the Jianghu (the martial arts world)”, became popular together, but the background music conveys a kind of despondency towards the disputes in the jianghu and a desire for freedom, which is not meaningfully related to the content of the dance, and the dance only creates visual stimulation, and the background music does not strengthen the relationship between the content of the picture, resulting in redundancy, but in the long term, the two have been bound to a fixed symbol.

The other novelty-hunting and ugliness-seeking style videos also have the problem of contradicting the seriousness of the subject matter with playful language, thus cancelling out the significance of the videos. In terms of value orientation, these works follow the creative logic of “entertainment first”, satisfying the audience’s curiosity and ugliness-seeking mentality through blunt and crude ways, with a significant logical break between their various modal forms, obviously showing the characteristics of form over substance, and the content value tends to be empty, even with bad value orientation, failing to provide the audience with a positive aesthetic experience and a cultural enlightenment.

In contrast, the rural original ecological style works show a world of difference in quality and value orientation:

- ➀

- Language and rhythm: the language of the works is straightforward and commonplace, but full of the flavour of life; the rhythm is soothing and fits the rustic style of idyllic life.

- ➁

- Content presentation: the work shows the true face of rural life, stresses the close connection between labour and nature, and conveys the traditional value of “one part of the work, one part of the harvest”.

- ➂

- Characters: the characters in the work have good qualities such as sincerity, kindness, and diligence, reflecting the core values of the Chinese farming culture.

- ➃

- The modes show complementary-non-reinforcement (covering crossover, union, and coordination) to complete the transmission of meaning.

The background music and shooting environment of Li Ziqi’s video are coordinated with the media systems such as characters’ movements and expressions, and the soothing soft music and beautiful rural scenery together with Li Ziqi’s natural movements and simple clothes constitute the discourse expression of rural life and traditional skills, which conveys the profound value orientation of Chinese traditional culture and makes the organisational framework of unity among the modalities appear.

In terms of value orientation, the rural original ecological works break through the city-centred narrative system and show the simplicity and innocence of Chinese farming civilizations through the combination of various modal forms, which not only show the “tǔ” in the bloodline of the Chinese people—down-to-earth, hardworking, simple, and natural—but also strengthen the cultural subjectivity through media communication, stimulating the audience’s recognition and praise of traditional farming culture.

Therefore, the rural original ecological style works are better than the novelty-hunting and ugliness-seeking style works in terms of the quality of media content and cultural value orientation. They not only achieve unity in multimodal forms and provide audiences with high-quality audiovisual experiences but also convey positive cultural values through media narratives, which is important for promoting Chinese farming culture and consolidating cultural subjectivity. Such differences reflect the cultural choices and values in media content creation and provide important case studies for media criticism and cultural communication research. The above can be summarised in Table 2:

Table 2.

Comparison of Heat, Quality, and Value Orientation of the Two Major Video Styles.

To summarise, in the current communication process, the phenomenon of semantic fragmentation of the “tǔ wèi” label is becoming more and more prominent: the label is used in both video styles, its use is too broad but cannot reach a unity in terms of the quality of the content and the value orientation, and its semantic orientation wavers between the representation of farming culture and a bad value orientation. In terms of content orientation, the coordination of multimodal relationships greatly affects content quality and cultural value. As for the current situation, under the impetus of traffic and heat, the chaotic relationship between the modes of the novelty-hunting and ugliness-seeking style video will aggravate the semantic fragmentation and the national cultural identity crisis, and the semantic fragmentation of the label of “tǔ wèi” will be tilted towards the vulgar orientation, which will bring about a complete devaluation of the emotional orientation of the “tǔ wèi” label, leading to cognitive bias in the public’s perception of the rural ecology and farming culture referred to by the “tǔ wèi” label, which is detrimental to the consolidation of the nation’s cultural subjectivity.

4. Causes of the Semantic Fragmentation of the “Tǔ Wèi” Label: Historical Roots and Platform Logic

The problem of semantic fragmentation of the “tǔ wèi” label has complex causes. In essence, the semantic fragmentation of the “tǔ wèi” label is the alienation of the meaning of the word “tǔ”, which represents the traditional Chinese farming culture. It is precisely because people’s understanding of the farming culture represented by “tǔ” has never been comprehensive and in-depth, and the recreation and development of the nation’s farming culture has never been sufficient, and they have not been able to build up a set of national farming narrative system. It is this failure that has given the words “tǔ” and “tǔ wèi” the opportunity to change or even alienate their meaning. This transformation and alienation are influenced by a variety of factors, which can be summarised in the following two aspects:

4.1. Historical Dimension: Clash of Civilizations and the Urban-Rural Dichotomy

The civilizational hierarchy of the modern era, in which “the earth and the sea are in opposition to each other”, and the urban–rural division policy of the planned economy have jointly shaped the stigmatising context of “tǔ”. In the process of urbanisation, the countryside has been constructed as a space of “backwardness”, resulting in “tǔ” becoming a projected symbol of cultural inferiority.

Clash of civilizationss between China and the West: In recent times, the clash of civilizations between China and the West has led to a change in the meaning of the word “tǔ”, and the formation of an antagonistic concept between “tǔ” and “foreign”, giving rise to the cultural root of “reverence for the foreign and dislike of the Chinese”. Since the beginning of the creation of the word “tǔ” is closely related to farming and agriculture, from the pre-Qin Dynasty to the Qing Dynasty, the farming lifestyle represented by “tǔ” is the basis for people to achieve self-sufficiency, which has always existed as the basis for the founding of the country. At the end of the Qing Dynasty, advanced science and developed industrial civilizations had a strong impact on China, which had been closed to the world for many years. Based on this, the concepts of “tǔ” and “foreign” became opposites, and the meaning of the word “tǔ” gradually changed to backward and out of fashion. The meaning of the word “tǔ” is gradually tilted towards backwardness and out-of-trend, giving the label “tǔ wèi” a linguistic basis for alienation, thus forming a set of comparative logic of “foreign” being good and “tǔ” being bad. As a result, for people on the “foreign” things, “foreign” culture has produced a worship of the psychological; on the contrary, in the face of agricultural, traditional “tǔ” things, people have produced an inferiority complex and negativity, resulting in “reverence for the foreign and dislike of the local” cultural roots.

Urban–rural dichotomy: The urbanisation process since the founding of New China has exacerbated the dichotomy between urban and rural areas, and the backwardness of living conditions in the countryside has given rise to feelings of inferiority and negativity when people are confronted with the countryside, which is represented by the word “tǔ”, thus aggravating the “backwardness” attribute of the “tǔ wèi” label. The process of urbanisation since the founding of New China has further aggravated the cultural root of “reverence for the foreign and dislike of the local”. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China and before the reform and opening up, China implemented a household registration system that separated urban and rural areas, strictly controlling the movement of rural residents to the cities (Bai 2012). Under the influence of the planned economic system, and in order to serve the needs of industrialisation, the development of agriculture was seriously hampered at the expense of agriculture, and the vast majority of peasants lived in a state of poverty for many years. This has led to a worsening of the urban–rural divide and the gradual formation of the urban–rural dichotomy.

Under the constraints of the household registration system, peasants are unable to flee the countryside and move to the cities in search of new development. Under such circumstances, the semantic meaning of “tǔ” is closely linked to backwardness, and the linguistic basis for the alienation of the “tǔ wèi” label is becoming deeper and deeper; at the same time, people’s longing for the city is also growing, and their inferiority complex and negativity towards “tǔ” are also becoming more and more serious. The dichotomy between urban and rural areas has yet to be resolved since the reform and opening up, and the rural areas are still more backward and marginalised than the cities. On the whole, the process of urbanisation has exacerbated the dichotomy between urban and rural areas and the contrast in values and further aggravated the “backwardness” of the “tǔ” labels representing rural areas, which has not only failed to diminish the national sentiment of “reverence for the foreign and dislike of the local”, but also has exacerbated the root causes of cultural ills.

4.2. Platform Mechanisms: Traffic Logic and Symbol Abuse

Short video platforms are dominated by algorithmic recommendations, and the novelty-hunting and ugliness-seeking-style videos are tilted to gain traffic due to “high interaction rate”, and the strong binding of multimodality is also used to achieve the purpose of “brainwashing” for viewers. At the same time, the platform’s generalised use of the “tǔ wèi” label has blurred its semantic boundaries, accelerated the negative turn of symbols, and exacerbated the problem of semantic fragmentation of the “tǔ wèi” label.

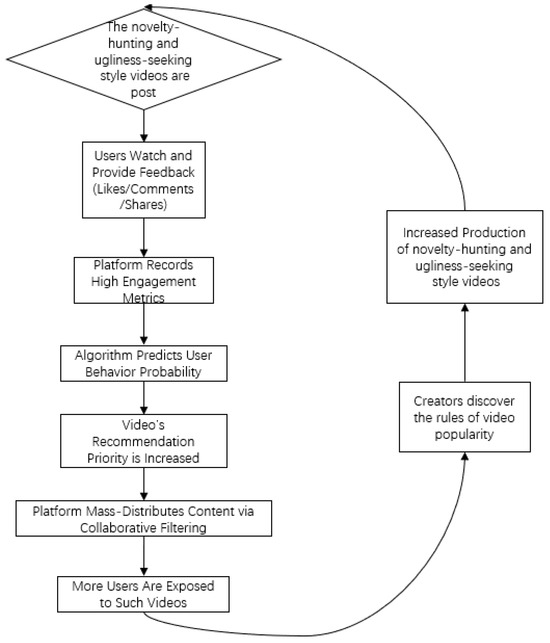

As for the creators, the creation of low-quality local flavour works meets their common needs for self-expression and money. The initial creators of “tǔ wèi” videos mainly come from youth groups in third- and fourth-tier cities or rural townships, which are often on the fringe of mainstream society and have been in a state of aphasia in the traditional discourse system for a long time. The downward shift of the discourse power brought about by short videos has broken the original discourse system. Among them, the novelty-hunting and ugliness-seeking style videos are easy to produce, have low costs and generate huge traffic. This kind of video creation meets their emotional needs for self-expression, and the attention and likes harvested in the video become the manifestation of their self-worth and sense of self-existence (Shi 2020, pp. 63–66), from which the township youths have “tasted the sweetness” and made money through the heat. Under the double impetus of traffic stimulation and the desire for expression, the short videos of novelty-hunting and ugliness-seeking style have grown rapidly, gradually occupying the mainstream of the “tǔ wèi” label and accelerating the alienation of the meaning of “tǔ wèi”. The principle of the above process can be summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The flowchart shows how the novelty-hunting and ugliness-seeking style videos have become the mainstream of the “tǔ wèi” label.

Platform mechanisms: short video platforms abuse the “tǔ wèi” label, pursue traffic-oriented push mechanisms, and, through the forced association of multimodal videos, take advantage of viewers’ viewing inertia to promote the dissemination of low-quality works, further worsening the semantic fragmentation of the “tǔ wèi” label.

On the one hand, short video platforms have over-generalised the “tǔ wèi” label. The works under the label of “tǔ wèi” on mainstream short video platforms are both good and bad, with varying quality of content and mixed reviews, and some of the works even have a tendency to be vulgarised and malignant.

On the other hand, the platform mechanism further worsens the semantic fragmentation of the “tǔ wèi” label. Firstly, short video platforms do not have good guidance and control over the creation of works that are ugly, strange, or even vulgar, which dominate the dissemination process by virtue of their quantity, with the support of factors such as simple production and huge traffic. Secondly, low-quality works occupy the quantitative advantage, the platform pursues the push mechanism of “traffic is king”, and under the drive of algorithms, the relationship between the novelty-hunting and ugliness-seeking style videos is strongly bound, and the platform is rapidly swept by exaggerated actions, brainwashing background music, and pompous oddity language, which makes use of its embarrassing and refreshing view and low-cost pleasure consumption to make viewers quickly “feel good”.

The short video platforms are to blame for the semantic fragmentation of the “tǔ wèi” label, as they make viewers quickly get “hooked” and harvest a lot of traffic and attention, fuelling the spread of this kind of low-quality works with a huge amount of traffic.

5. Impacts and Responses to Semantic Fragmentation: Based on a Cultural Subjectivity Perspective

5.1. The Impact of the Semantic Fragmentation of the “Tǔ Wèi” Label—Analysing Cultural Cognitive Bias and the Crisis of Subjectivity

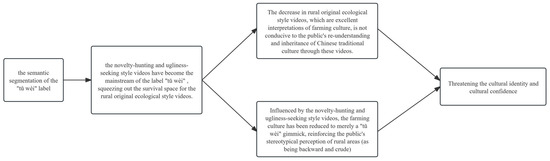

Semantic fragmentation has led to the simplification of farming culture into “tǔ wèi” gimmicks, which will deepen the public’s stereotypical image of the countryside. The proliferation of vulgar content squeezes the space for the dissemination of original works and shakes the foundation of cultural inheritance. Based on the perspective of the communication process, the semantic fragmentation of the “tǔ wèi” label hinders the creation and dissemination of the rural original ecological style videos.

On the one hand, as these works share the label of “tǔ wèi” with a large number of low-quality works, under the influence of the platform’s pushing mechanism, these works are easy to be submerged in the trend of low-quality works and fall into the vicious circle of insufficient traffic and insufficient pushing, as well as insufficient pushing and insufficient traffic.

On the other hand, the difficulties in dissemination mean that it is difficult to realise the traffic and more likely that the creation of the rural original ecological style videos will fall into the lowest point, which will further contribute to the dominance of low-quality works.

Further, the obstruction of the creation and dissemination of the rural original ecological style videos has had a negative impact on the development of Chinese farming culture, jeopardising the consolidation of cultural subjectivity, and is not conducive to the establishment of national cultural self-confidence. The consolidation of cultural subjectivity must be based on the correct knowledge and continuation of the excellent traditional Chinese culture, and the semantic fragmentation of the “tǔ wèi” label has brought obstacles to the dissemination of works that represent the national farming culture and reduced the opportunities for the public to contact, know, and understand the national farming culture.

Worse still, the low-quality works that dominate the label stereotype and vilify the image of rural people, exaggerating the ignorant, backward, and vulgar elements in them, which tend to deepen the public’s misunderstanding of farming culture, make it impossible to eliminate the erroneous labels of ignorance and backwardness. What is even more alarming is that the label of “tǔ wèi” has a negative tendency to become more and more vulgar and vicious on the basis of semantic fragmentation. Linking the derogatory “tǔ wèi” label with the unique farming culture of the nation is likely to cause bias in the public’s perception of the national culture and aggravate the cultural root of “reverence for the foreign and dislike of the local”.

The above can be summarised in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A flowchart illustrating the process by which the semantics segmentation of “tǔ wèi” label threatens the cultural subjectivity and cultural confidence.

5.2. Proposed Reconstruction of Pathways: Reflections Based on the Consolidation of Cultural Subjectivity

Based on the perspective of consolidating cultural subjectivity, the problem of semantic fragmentation of the “tǔ wèi” label is related to the development of national farming culture and the establishment of national cultural confidence, and it should be taken seriously and solved, which can be done from the following three aspects:

Firstly, the activation of “tǔ” cultural resources and the consolidation of the foundation of cultural subjectivity.

At present, there is obvious homogenisation in the creation of rural ecological works, limited to the recording of daily life in the countryside. Due to the popularity of the head blogger Li Ziqi, Student Zhang, and others, some self-media farmers and commercial teams began to blindly follow the trend, “mechanised” to produce a large number of similar works, the result of the use of professional technology and the optimisation of the content is not fit enough (Deng 2024).

In this regard, in the field of cultural research, it is recommended to increase policy support and encourage experts and scholars to carry out research on relevant topics, explore the multifaceted contents of “tǔ” culture, and enrich “tǔ” cultural resources. In the field of creative works, it is recommended to strengthen the combination of theory and creative practice, led by the official, in cooperation with experts and scholars, to explore novel content themes, broaden the types of the rural original ecological style. In addition, the relevant departments should take training as a tool, give play to the leading and teaching role of the inheritors of agricultural cultural heritage, and improve the media literacy and cultural literacy of the main body of rural cultural communication, as well as provide hardware support and guide and regulate the video creators in the form of creation bases and so on. Through the research and excavation of various aspects of “tǔ” culture and farming culture, the public will be able to establish a correct perception of Chinese culture and consolidate the resource base of cultural subjectivity.

Secondly, optimise the algorithmic mechanism to achieve the return of “tǔ” ideograms.

At the level of work circulation, short video platforms should accelerate the improvement of the content review mechanism and realise the elimination of the bad and the retention of the good. The platform should strictly screen the content of the works, strengthen the quality control of the works, strictly prohibit vulgar works to enter the field of communication, and vigorously promote the display of various aspects, including a deep interpretation of Chinese “tǔ wèi” culture of excellent works, to achieve the effect of the good money to expel the bad money, reversing the ecology of the use of the label “tǔ wèi” so that the label “tǔ wèi” to return to a positive value orientation.

At the level of word use, the undesirable tendency of using “tǔ wèi” labels should be resisted, and the use of “tǔ wèi” labels should be correctly guided in communication. The emotional colour of words should be guided to match the application scene, and the use of the “tǔ wèi” label should be denied for low-quality or even vulgar works, and words with derogatory colours such as low, bad, and terrible should be used to express the correct emotional orientation so as to curb the pejorative orientation of the “tǔ wèi” label. It will change the negative perception of the public towards traditional farming culture and guide people to correctly perceive, inherit, and develop the culture of “tǔ wèi”, which will firmly establish the cognitive foundation of cultural subjectivity.

Thirdly, reconstruct discourse contexts and uncover multiple vocabulary uses.

The construction of cultural discourse cannot be separated from the role of linguistic context, and we should play a positive role in correcting the semantics of the “tǔ wèi” label by using a positive cultural context. It is suggested to actively organise cultural activities with original characteristics of the countryside, such as CBA in the countryside and village’s exercises, and the official media should take the lead in reconstructing the original meaning of the “tǔ wèi” label by using the cultural context so that the “tǔ wèi” label can be linked to positive emotions such as fondness and praise in order to help solve the problem of “revering the foreign and dislike of the local”. In view of the present situation of “tǔ wèi” labels being ideologically fragmented, we should make full use of the Chinese language’s advantage in word formation to explore more diversified vocabularies to portray and describe the Chinese farming culture.

Currently, descriptions of rural life and farming culture are still limited to a few words, such as “tǔ “ and “tǔ wèi” labels, and there is a lack of newer, more accurate, and positive words to use. The official media should play an exemplary role, taking into account the current situation of Chinese language use in society, especially on the Internet, to find more versatile and accurate words to disseminate farming culture, and to promote people’s understanding and recognition of farming culture so as to consolidate the emotional foundation of cultural subjectivity and to help build up cultural self-confidence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Q.; methodology, W.Q.; software, T.F.; validation, X.Z., T.F. and W.Q.; formal analysis, X.Z.; investigation, X.Q.; resources, X.Z.; data curation, T.F.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Q. and W.Q.; writing—review and editing, X.Z. and T.F.; visualization, X.Q.; supervision, X.Z.; project administration, X.Z.; funding acquisition, X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China, grant number 21BSH052.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data were obtained from New Rank (新抖—短视频及直播数据工具) and are available [from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of New Rank].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the Data Availability Statement. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Bai, Yongxiu. 2012. China’s Perspective on the Urban-Rural Dual Structure: Formation, Expansion, and Paths. Academic Monthly 44: 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Baudrillard, Jean. 2000. Consumption Society. Nanjing: Nanjing University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 2015. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yawei. 2019. Underground Performances and the Carnival of Disgust: A Perspective on the Youth Subculture of “tǔ wèi” Culture. Southeastern Communication 4: 75–77. [Google Scholar]

- Debord. 2017. The Society of the Spectable. Nanjing: Nanjing University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Dengyao. 2024. Realistic Reflection on the Production of “Agriculture, Rural Areas, and Farmers” Short Videos from the Perspective of Rural Revitalization. Tianfu New Perspectives 4: 115–25+158. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, Xiaotong. 2012. From the Soil. Beijing: Peking University Press, p. 107. First published 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Stuart. 1980. Encoding/decoding. In Culture, Media, Language. Edited by Stuart Hall, Dorothy Hobson, Andrew Love and Paul Willis. London: Hutchinson, pp. 128–38. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Li. 2020. From Disenchantment to Reenchantment: Rural Microcelebrities, Short Video, and the Spectacle-ization of the Rural Lifescape on Chinese Social Media International. Journal of Communication 14: 3769–87. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, Yang, Mark Zhenhao Meng, and Yunzi Zhang. 2022. Constructing a virtual destination: Li Ziqi’s Chinese rural idyll on YouTube. Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism 22: 279–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, Henri. 2022. The Production of Space. Beijing: Commercial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Wenyong. 2007. The Darling of Modern Communication—Viral Communication. Southeast Communication 9: 54–55. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Yixuan, and Jiayu Zhu. 2022. Performance Carnival and Rural Imagination: A Study on the Production and Consumption of Vulgar Videos from the Perspective of Transmission and Reception. Qi Ke Xuekan 1: 210–30. [Google Scholar]

- New List Data. 2024. Tik Tok Data Tool—New Jitter [EB/OL]. Available online: https://xd.newrank.cn/home?type=1074&source=10000&l=ys_xd-t_sjfw_xd. (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Nicola, Davis. 2017. The Selfish Gene. London: Macat Library. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Pengfei. 2020. An Insight into the “Vulgar Culture” Communication Phenomenon in the Era of Short Videos. China Radio and Television Journal 4: 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Shun Pao. 1905. Request for Industrialization. Shanghai: Shun Pao. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Ziqi. 2021. Research on the Dissemination of Online “Tǔ Wèi” Culture Under the Perspective of Post—Subculture. Suzhou: Soochow University. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, Jinping. 2023. Speech at the symposium on cultural heritage development. Seeking Knowledge 9: 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Shen. 2015. Shuowen Jiezi. Beijing: Zhong Hua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Delu. 2009. Exploration of the Comprehensive Theoretical Framework for Multimodal Discourse Analysis. Chinese Foreign Language 6: 24–30. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).