Embedding Critical Thinking in Global Virtual Exchange—Teaching Sociology Across National Borders in Virtual Classrooms

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background of Virtual and Experiential Learning

1.2. Critical Thinking in Sociological Teaching

2. Research Context and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Findings

3.1. Experiential Learning as a Process of Critical Thinking

3.1.1. Experiential Learning—Sharing COVID-19 Experiences

“The epidemic has had a lot of impact on our lives and changed many of our original living habits. For example… we learn to go to hospitals, courts, and various offices to avoid crowded queuing, and judges even hold online sessions during the epidemic prevention and control period.”

“Much of the country was locked down, and the public began wearing masks and social distancing to protect ourselves from this new disease. But over time, COVID-19 culture became somewhat normal, as putting on a mask was like putting on a shirt.”

“After about two weeks in, I had enough of watching Netflix, sleeping and sitting in my house. I felt tired all the time even though I was doing nothing. I lost my desire to do things and make plans because my situation felt hopeless.”

“First, people infected with COVID-19 suffer from psychological problems caused by the strange eyes and rejection of those around them. Second, the closed space isolation measures taken to prevent COVID-19 make people isolated from the outside environment, depriving people of their sense of social existence and easily making people fall into depression.”

3.1.2. Experiential Learning—Comparing Healthcare Systems

3.1.3. Experiential Learning—Comparative Pension Systems

“My parents’ pension includes basic pension, personal account pension, commercial pension insurance and personal savings. They have joined the government’s public pension plan, which allows citizens who have retired and contributed for 15 years to receive monthly pensions.”

“I find that my grandparents also receive the most basic pension due to their tax contributions were not up to the amount required, they also came to America at the older age and work almost illegally for quite sometime before they are qualified for citizenship. Causing them to lose years of Tax report and pushed them into the most basic pension for elders. For my parents, since they are the second generation, they are able to get a better pension and investment in both private and public ones.”

“I find that the amount of pension received by people of different occupations in China will vary greatly. Civil servants receive good pensions. They often live a rich life and can enjoy retirement without the pressure of life. However, pensions of many occupations are still not guaranteed. For example, some temporary employees and some low-income occupational units pay very little pensions, which makes their lives insecure.”

“Great post! My father worked for the state government for over 35 years and is going to get a great pension… In addition to receiving a pension from the government, which will be about 90% of his highest paycheck until death, my father will also receive social security. My mother is retired from CNN and has a 401 k that the company has helped match throughout the duration of her employment…”

3.1.4. Experiential Learning—Cross-Cultural Differences in Intergenerational Relations

“To simply put it, the grandchildren are not their children! We cannot expect grandparents to bear that responsibility. There are some cases in which this is applicable and okay, but it ultimately depends on the grandparents and their wishes. Sometimes that can be challenging as the age gap is too much, and how can we expect an older person who has needs of their own to take care of children? Also, the grandchildren might not be able to receive the full care and attention they need. As we age, we face barriers, and our life expectancy shortens. The timespan to raise a child is long and so that might be tough to think about.”

“… The advantage is that it can reduce the cost of hiring a nanny for the family, relieve the financial pressure of the adult children and allow them to focus on their work. Meanwhile, taking care of the grandchildren can also give the grandparents a sense of social value and happiness. The disadvantage is that the grandparents will feel tired in the process of taking care of their grandchildren, which will affect their health. In addition, the phenomenon of overindulgence of grandchildren is also relatively common, which is not conducive to the healthy growth of children. These issues require families to find a balanced point.”

3.2. Embedded Critical Thinking in Learning Projects—Global and Comparative Lens

4. Discussions

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Learning Project 1 Assignment Details

- Comparative Understanding of Health Care Systems

- Step 1

| Health care Models | Countries | Your choice (select your country) Sign your name next to the country |

| Group 1 The Bismarck Model | Germany | |

| The Netherlands | ||

| Switzerland | ||

| Japan | ||

| South Africa | ||

| Austria | ||

| Group 2: The Beveridge Model | United Kingdom | |

| Italy | ||

| Spain | ||

| Norway | ||

| Finland | ||

| Sweden | ||

| Denmark | ||

| New Zealand | ||

| Hong Kong | ||

| Cuba | ||

| Group 3: The National Health Insurance Model | Canada | |

| Taiwan | ||

| South Korea | ||

| Australia | ||

| Costa Rica | ||

| Russia | ||

| Group 4: African Countries | Egypt | |

| Nigeria | ||

| Kenya | ||

| Morocco | ||

| Ethiopia | ||

| Tunisia | ||

| Congo | ||

| (Add your own) | ||

| 5. Asian countries | China | Everyone has to study it |

| India | ||

| Vietnam | ||

| Thailand | ||

| The Philippines | ||

| Malaysia | ||

| Laos | ||

| Indonesia | ||

| (Add your own) | ||

| 6. North And South American Countries | The U.S. | Everyone has to study it. |

| Mexico | ||

| Panama | ||

| Peru | ||

| Brazil | ||

| Argentina | ||

| Venezuela | ||

| (Add your own Choice) |

- Learning Project 1 (30 pts): Step 2

- Due: 9/25 11:59 p.m. U.S. Eastern time in Discussion and Assignment folders for American students

- 11:59 a.m. 9/26 Beijing time for students in China

- 1.

- Population Aging status: What is the total population of China, the U.S., and the country you selected in 2020? What is the life expectancy at birth in 2020 for all citizens of these 3 countries? What is the percentage of 65+ in 2020? What is the fertility rate (birth per woman) in this country?

- 2.

- What percentage of GDP is spent on the public health expenditure in Healthcare in these 3 countries? Use:

- 3.

- GDP/Capita: What is the GDP (Gross Domestic Product) per capita of these 3 countries?

- 4.

- Physician/1000: How many physicians are there per 1000 people in this country?

- 5.

- Access: Is health care coverage universal, or targeted? Can the poor afford health care or have access to healthcare? Briefly describe the healthcare system in this country.

- 6.

- Finance: How is health care financed in this country? Is it through a national tax paid by everyone? Or through individual/employer contribution? Or out of pocket? Or mixed model. Briefly describe your understanding of health care of these 3 countries.

- 7.

- Private vs. Public: What is the role of private ownership in the health care system of this country? Is profit-making and market competition (for patients and medicine) an important part of the healthcare system? Fill in the table below for your own country

| Life Expectancy | GDP/per Capita | # of Doc per 1000 | Access to Healthcare | Who Pays? (Financing) | Role of Private Market | |

| Country you select | ||||||

| The U.S. | ||||||

| China |

- (1)

- How do these 3 countries compare in healthcare access, financing, and the role of the market?

- (2)

- Which country, among the 3, has the best or most broad coverage for all its citizens?

- (3)

- Compare the 3 systems of healthcare financing, which approach appears to be the most efficient and effective? Why do you think so?

- (4)

- Is the role of the private market beneficial for patients and healthcare? Why do you think so?

- Group Project 1: Summary Paper (30 pts)—Step 3

- due: 10/2 in Assignment and Discussion folders (a week after the individual paper)

- Read 4 of your group member’s papers to read, including the country you studied, you should have 6 countries in your summary papers--spell out which four countries you are reading and comparing. Then answer the following question: (10 pts)

- 8.

- Compare the 6 countries you have selected (4 plus China and the U.S.), which country has the highest and lowest life expectancy?

- 9.

- Which country has the highest and lowest GDP per capita?

- 10.

- Which country has the highest and lowest number of physicians per 1000 people?

- 11.

- Do these factors (life expectancy, GDP per capita, and # of physicians per 1000 people) go hand-in-hand or correlate with health care coverage (breadth) and access in the country? Does the highest GDP per capital and highest healthcare expenditure always translate to higher life expectancy of the country?

- 12.

- Based on your understanding of health care systems in these countries, and your understanding of the U.S. system of health care, how does the U.S. compare to these nations in health care access and coverage?

- 13.

- Based on your understanding of healthcare systems in these 6 countries and your understanding of China’s systems of health care, how does China compare to these nations in health care access and coverage?

- 14.

- For American students: What is the major problem in the U.S. healthcare system (such as major social inequalities in access, delivery, and management of healthcare)? What should the U.S. government do? Which aspects can the U.S. adapt and/or borrow from each or any of these countries you have studied to make an efficient health care system with universal coverage in the U.S? Give your personal and innovative suggestions for healthcare reform in the U.S. with the insight from knowing other healthcare systems.For Chinese students: What is the major problem in the Chinese health care system (such as major social inequalities in access, delivery, and management of healthcare)? What should the Chinese government do? Which aspects can the Chinese government adapt and/or borrow/learn from other countries you studied to make a more efficient healthcare system with universal coverage in China? Give your personal and innovative suggestions for healthcare reform in China with the insight from knowing other healthcare systems.

- 15.

- Provide information for each of the 6 countries in the following Summary table (5 pts)

| Ttl Pop. | Life Expectancy | GDP/per Capita | # of Doc per 1000 | Health Expenditure per Capita | Universal or Not? Access? | Who Pays (Financing) | Role of Private Market | |

| The U.S. | ||||||||

| China | ||||||||

| Country 1(yours) | ||||||||

| Country 2 | ||||||||

| Country 3 | ||||||||

| Country 4 |

- Group Presentation—Step 4

- Time and date: 10/6/2022 8:30 p.m. Eastern Time in the U.S.;

- 10/7/2022 8:30 a.m. Beijing time

- Slide 1: List the countries represented and names of students in the group

- Slide 2: present the table that contains all the information requested in Summary paper for all the countries in the group. At this time Each student should say a few words about the country, not to repeat the information in the table, but explain the healthcare system financing, access, and delivery. You may also highlight major challenges facing this country’s healthcare system.

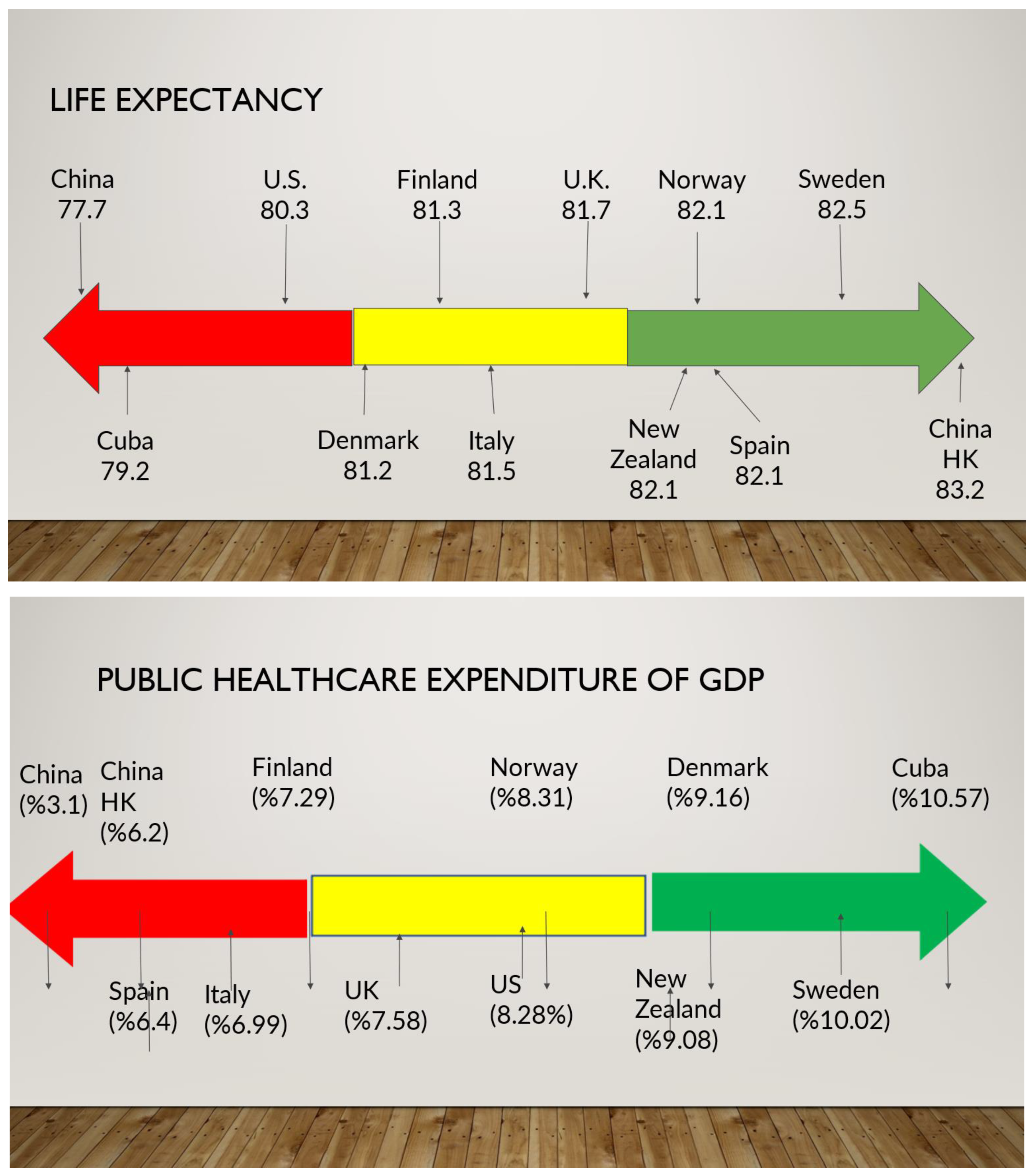

- Slide 3: Create a continuum of life expectancy of the countries studied in your group.

- Slide 4: Create a continuum of GDP per capita of the countries studied in your group

- Slide 5: Create a continuum of the number of doctors per 1000 population.

- Slide 6: create a continuum of public healthcare expenditure of GDP.

- Slide 7: Create a continuum of the access to healthcare, from the least to the most/best access.

- Slide 8: Discuss the patterns of financing among the countries studied—try to make sense of the models, approaches, ways of financing healthcare; the strength and weakness of each model or approach.

- Slide 9: What is the role of the private market in health care among all the countries studied in your group? What is your opinion (you do not have to agree, just spell out different opinions briefly)?

- Slide 10: For American students: what have you learned from doing this project? Give 3–5 specific suggestions for fixing American healthcare.

- Slide 11: For Chinese students: What have you learned from doing this project? Give 3–5 specific ideas that you think the healthcare system can be improved in China.

- Slide 12: Mutual insight: What do American students think the strength and weakness of Chinese health care practices; What do Chinese students think about the strength and weakness of American healthcare practices?

Appendix B. Rubric for Evaluating Group Presentations of Comparative Learning Projects

- Group Presentation Criteria for Comparative Learning projects

- Scored between 1 to 100 as a group

- Have all the students who signed up participated in the recorded group presentation?

- Take 2 points off for each missing student in audio presentation.

- 2.

- Is the table fully filled with understandable details?

- Take a 1-point deduction for each empty cell, among all countries in the group.

- 3.

- Are the continuums making sense based on the data presented in the table?

- Are all the countries included in the continuum for Slides 3–7, take 1 point deduction for each missing country in each continuum.

- Are all 5 continuums included? Each missing continuum has 2-points off.

- Are the continuums visually clear/understandable for readers?

- 4.

- Visual effect: are this Group’s Power Point Presentation slides visually appealing?

- Are the slides appealing to look at? After reading/listening to all groups, rate by the most and least appealing, the most being 10, the least being 5.

- Are there creative details that make this presentation stand out? Again, compare the groups, make the most creative a “10”; least creative a “5”.

- Are there techniques to enhance learning? After comparing all groups, rate the best/most technically savvy group by 10, the least by 5.

- 5.

- Content: Are the contents of each country logical and directly answering all questions raised?

- 6.

- Comparative scope: Is the group providing a group comparative scope among the countries?

- 7.

- Is there a thoughtful discussion of “patterns of financing” for healthcare and sustainability of healthcare in the presentation?

- 8.

- Is there a thought-provoking discussion about the “role of the private market” in healthcare in comparison among the countries in the group? Are these discussions sociological?

- 9.

- Are there meaningful insights about how to fix American (for American students) or Chinese (for Chinese students) healthcare? Are these comments sociological, thought-provoking, and thoughtful?

- 10.

- Is the group presentation coherent: Do the group members appear to have prepared for their group activities adequately before they come to record the presentation?

References

- Alami, Nael H., Josmario Albuquerque, Loye Ashton, James Elwood, Kwesi Ewoodzie, Mirjam Hauck, Joanne Karam, Liudmila Klimanova, Ramona Nasr, Müge Satar, and et al. 2022. Marginalization and underrepresentation in Virtual Exchange: Reasons and Remedies. Journal of International Students 12: 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, Ronald. 1997. Higher Education: A Critical Business. Buckingham: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, John. 1997. Teaching across and within cultures: The issue of international students. In Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: Advancing International Perspectives: Proceedings of the Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia Conference, Adelaide, South Australia, 8–11 July 1997. Canberra: National Library of Australia, pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Virginia, and Victoria Braun. 2018. Using thematic analysis in counselling and psychotherapy research: Critical reflection. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 18: 107–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commander, Nannette Evans, Wolfgang F. Schloer, and Sara T. Cushing. 2022. Virtual Exchange: A Promising High-Impact Practice for Developing Intercultural Effectiveness across Disciplines. Journal of Virtual Exchange 5: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, Gareth. 2020. The China-US blame game: Claims-making about the origin of a new virus. Social Anthropology 28: 250–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duch, Barbara J., Susan E. Groh, and Debrah E. Allen. 2001. The power of problem-based learning: A practical “how to” for teaching undergraduate courses in any discipline. Stylus Education Science 2: 190–98. [Google Scholar]

- Egege, Sandra, and Salah Kutieleh. 2004. Critical thinking: Teaching foreign notions to foreign students. International Education Journal 4: 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Eseverri-Mayer, Cecilia. 2024. The fight against islamophobia in Madrid, Paris and London. A comparative and qualitative analysis on Muslim activism in three cities. Islamophobia Studies Journal 8: 169–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froese, Febian Jintae, Tobias Blay, Cristina B. Gibson, Magaret A. Shaffer, and Jose Bonitez. 2025. Global virtual work: A review, integrative framework, and future opportunities. Journal of International Business Studies 56: 691–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, Ronald E. 2013. Encouraging Critical Thinking Skills among College Students. The Exchange—The Academic Frum 2: 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hammersley-Fletcher, Linda, and Christopher Hanley. 2016. The use of critical thinking in higher education in relation to the international student: Shifting policy and practice. British Educational Research Journal 42: 978–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- iEARN.org. 2007. The New York-Moscow Schools Telecommunications Project The Founding Project of iEARN: A Comparative Program Analysis of New Your Schools and Their Interactions with Their Russian and Chinese Counterparts. Available online: https://iearn.org/assets/general/iEARN_NY-Moscow_Evaluation.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Ito, Kasumi. 2024. Between global north and south: Global grass-roots movements of people with psychosocial disabilities in East Asia. International Journal of Disability and Social Justice 4: 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozimor, Michele Lee. 2020. Editor’s comments: Three teaching takeaways from the COVID-19 Pandemic. Teaching Sociology 48: 181–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jonathan, Jami Leibowitz, Jon Rezek, Meghan Millea, and George Saffo. 2022. The impact of international virtual exchange on student success. Journal of International Students 12: 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Yun Zhen, Ke Zhu, and Ceng Ling Zhao. 2017. An empirical study on the depth of interaction promoted by collaborative problem solving learning activities. Journal E-Education Research 38: 87–92. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Wei, David Sulz, and Gavin Palmer. 2022. The Smell, the Emotion, and the Lebowski Shock: What Virtual Education Abroad Cannot Do? Journal of Comparative and International Higher Education 14: 112–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Jiali, and David Jamieson Drake. 2015. Predictors of study abroad intent, participation, and college outcomes. Research in Higher Education 56: 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dowd, Robert. 2017. Virtual Exchange and Internationalising the Classroom. Training Language and Culture 1: 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyer, Mehmet, Gina McCrackin, Sebahattin Ziyanak, Jennifer Given, Vonda Jump, and Jessica Schad. 2023. Leaving the lectures behind: Using community-engaged learning in research methods classes to teach about sustainability. Teaching Sociology 51: 151–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens Initiative. 2020. Virtual Exchange Impact and Learning Report. Washington, DC: Aspen Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Vásquez, Heydi Tananta. 2022. Higher Education in Pandemic Times. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice 22: 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittington, Frank J., Suzanne R. Kunkel, and Kate de Medeiros. 2021. Global Aging—Comparative Perspectives on Aging and the Life Course, 2nd ed. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Eric, Day Wong, Waqar Ahmad, and Rafia J. Mallick. 2024. Doing Sociology across Borders: Student Experiences and Learning with Virtual Exchange in Large Introductory Sociology Classes. Teaching Sociology 52: 323–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Eenwei, Wei Wang, and Qingxia Wang. 2023. The effectiveness of collaborative problem solving in promoting students’ critical thinking: A meta-analysis based on empirical literature. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 10: 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zak, Anna. 2021. An integrative review of literature: Virtual exchange models, learning outcomes, and programmatic insights. Journal of Virtual Exchange 4: 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Hongmei, Jian Wu, Yanju Li, Chad Marchong, David Cotter, Xianli Zhou, and Xinhe Huang. 2025. The impact of Virtual Exchange on College Students in the U.S. and China. Social Sciences 14: 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Yuefang, Divya Jindal-Snape, Keith Topping, and John Todman. 2008. Theoretical models of culture shock and adaptation in international students in higher education. Studies in Higher Education 33: 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicators | Frequency | Context | Frequency | Themes, Categories | Critical Thinking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 | 190 | COVID-19 impacted college life | 15 | Social contexts | Comparative |

| COVID-19 impacted opportunities | 7 | Contextual differences | Comparative | ||

| Have had COVID-19 | 9 | Mostly (all) Americans | Experiential | ||

| COVID-19 affects view of life | 5 | Comparative | Experiential | ||

| Discrimination against COVID-19 patients | 6 | Social contexts | Comparative | ||

| COVID-19, vaccine, and healthcare | 9 | Comparative | Comparative | ||

| COVID-19 and mental health | 10 | Personal, experiential | Experiential and comparative | ||

| COVID-19 and technology use | 9 | Comparative | Experiential and comparative | ||

| Healthcare | 139 | During COVID-19 | 22 | Healthcare context | |

| Compare U.S. healthcare systems to others (access and cost) | 12 | Healthcare systems | Comparative understanding | ||

| Healthcare experiences (access, cost) | 11 | Healthcare experience | Experiential learning | ||

| Healthcare in developed countries (insurance, access) | 9 | Compare systems | Comparative | ||

| Healthcare coverage | 6 | Coverage | Comparative and experiential | ||

| Universal healthcare | 10 | Access | Comparative and experiential | ||

| Is healthcare price fair in the U.S.? | 5 | Pricing fairness | Comparative and experiential | ||

| Healthcare is not fair (access) | 4 | Fairness | Comparative and experiential | ||

| Healthcare is a human right (access) | 4 | Access | Comparative and experiential | ||

| Avoid healthcare due to cost | 5 | Access | Comparative and experiential | ||

| Grandparents | 97 | Grandparents caring for grandchildren | 16 | Pros and cons | Cultural difference |

| Skipped generation | 8 | Social contexts | Social contexts | ||

| Grandparents’ pension | 11 | Social systems | Comparative understanding | ||

| Take care of grandparents | 13 | Familial care | Cultural norms and expectations | ||

| Love, providing love | 12 | Cross-cultural | Comparative experiential | ||

| Retirement | 65 | Retirement plans in America | 10 | Social systems | Experiential and comparative |

| Retirement and eldercare | 8 | Familial and social care | Experiential and comparative | ||

| Retirement and pension | 7 | Financial care | Experiential and comparative | ||

| Retirement and quality of life | 12 | Financial securities | Experiential and comparative | ||

| Retirement home | 7 | Familial and community | Personal, familial, community |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhan, H.J.; Liu, J. Embedding Critical Thinking in Global Virtual Exchange—Teaching Sociology Across National Borders in Virtual Classrooms. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 487. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080487

Zhan HJ, Liu J. Embedding Critical Thinking in Global Virtual Exchange—Teaching Sociology Across National Borders in Virtual Classrooms. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(8):487. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080487

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhan, Heying Jenny, and Jing Liu. 2025. "Embedding Critical Thinking in Global Virtual Exchange—Teaching Sociology Across National Borders in Virtual Classrooms" Social Sciences 14, no. 8: 487. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080487

APA StyleZhan, H. J., & Liu, J. (2025). Embedding Critical Thinking in Global Virtual Exchange—Teaching Sociology Across National Borders in Virtual Classrooms. Social Sciences, 14(8), 487. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080487