Cultural, Ideological and Structural Conditions Contributing to the Sustainability of Violence Against Women: The Case of Bulgaria

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. The Bulgarian Context

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Sample, Data Collection, and Method of Analysis

4.2. Ethical Considerations

5. Results

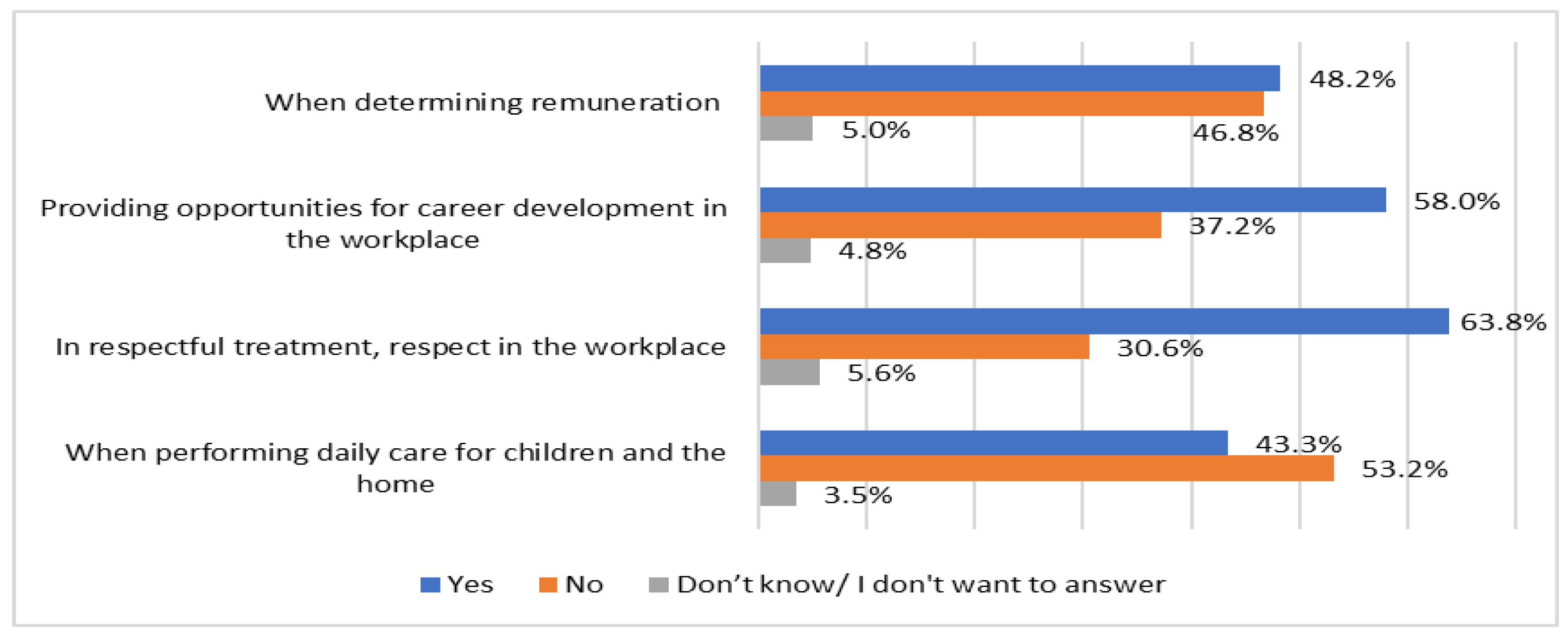

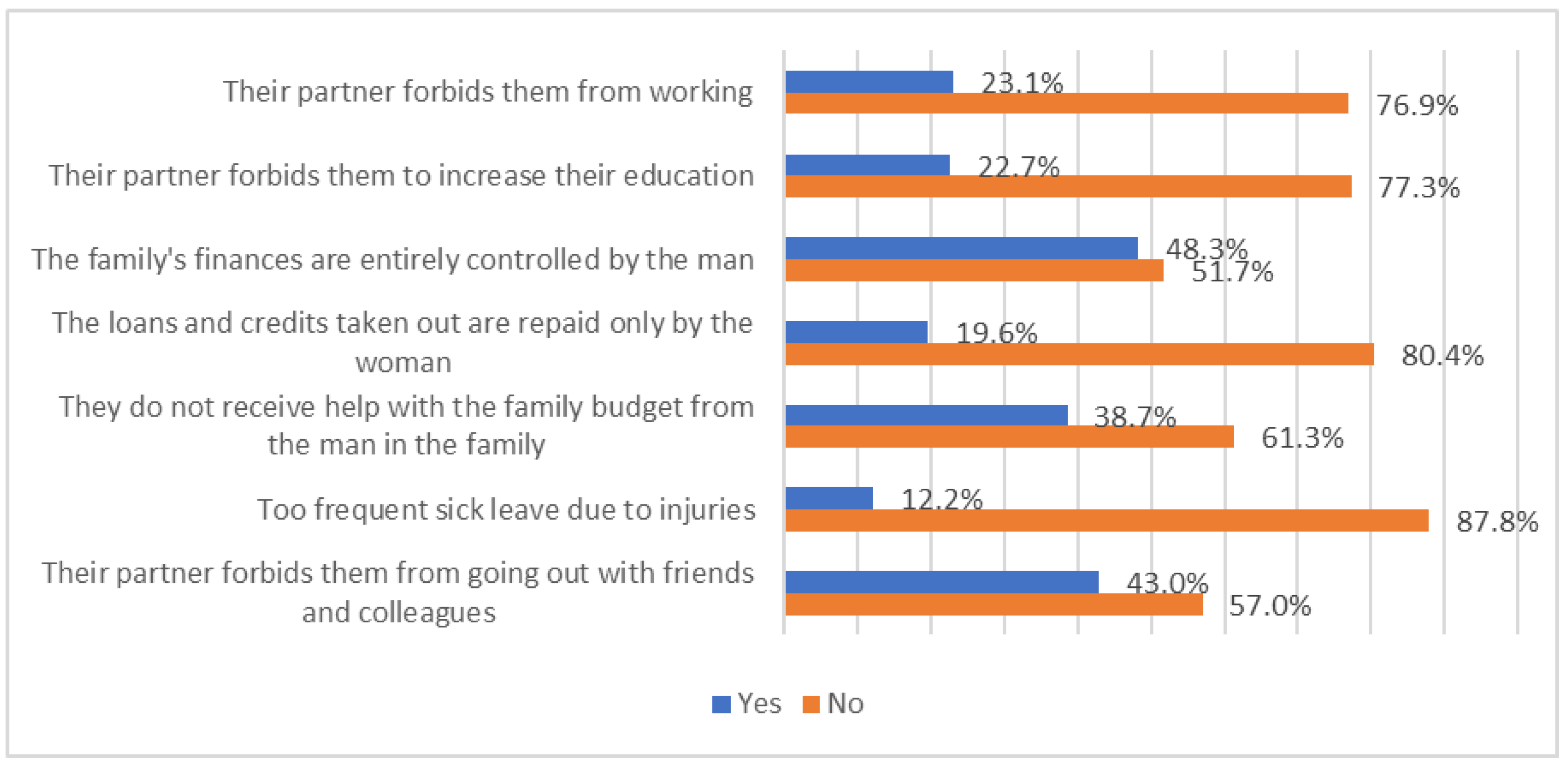

- Gender inequality in the family

- Cultural norms normalizing violence

- Ideological concepts shifting the blame to the victim

- State incapacity—impunity, ineffective protection, weak support, and no prevention.

“I mean, apparently women have rights, apparently they are equal, but in reality, they are dominated by patriarchal attitudes in our culture. That is, the Bulgarian family is still patriarchal for the most part, [...]. But in general, our society is extremely patriarchal [...]. Women are still dependent on male culture in this country.”(iDI-21)

“But nevertheless, my observation is that in most cases men develop this sense of [being] the stronger sex and the expectation that the weaker sex must conform to its demands. When she doesn’t respond in the way he expected, then violence is resorted to. And we can say that this violence against the other person is gender-based.”(iDI-53)

“Because there are regions in our country where this patriarchal family model, the man is in lead, he works, he earns money, he takes care of the family. As far as I think, [in] larger cities, like, say, the capital, women, by themselves, are beginning to change that role through the job, the financial resources they have.”(iDI-12)

“When she accepts a slap and he is saying: ‘but I only slapped her‘. Or ‘I just took her out on the terrace’, as was my last case, ‘to stand outside for a while because she hadn’t prepared a meal. It is not domestic violence, according to her, to stand with the child on the terrace locked for six hours because the meal had not been cooked. So, it’s accepted as something normal.”(Participant 8, FG-01)

“A lot of people viewing from the side accept it as normal because they say to themselves, it is not their problem. And so, the real victims are not seen […]. A lot of people turn a blind eye and don’t want to meddle in other people’s family problems.”(Participant 14, FG-01)

“But what I observe is that people are reluctant to interfere in the problems of other people’s families. And people are of the opinion, ‘why are you interfering in my personal business? It’s my problem, it’s my family’. So, I think, yes, the attitude is mostly that they shouldn’t interfere in these problems.”(iDI-23)

“And since violence and abuse are so widely tolerated in all aspects of life, I’m not just talking about domestic violence, but the work of one NGO is a drop in the ocean amidst all this. For example, the ‘90s, for example, this whole phenomenon of the ‘90s, which is still flourishing and, to this day, is actually objectifying women as sexual objects, validating gender inequality, normalizing aggression, and these messages are very strongly assimilated and very transgenerational.”(iDI-21)

“Probably, society has largely adopted such a mindset, that if the victim has allowed herself to a certain behavior, then it is her own fault.”(iDI-22)

“In addition, I think there are also many cases that have not reached the police because many people are silent, tolerant, accepting and this is due to shame. I have been living in a village recently, maybe approximately the last two years, in a village close to the city, and what impresses me is that I already know of 3–4 cases of domestic violence on my street. And the people have never sought support.”(iDI-23)

“There are measures, there are policies, but the fact that this phenomenon continues to grow tells us that these measures are not sufficient or are not having the desired effect at this time and at this stage […] I have spoken to victims who tell me they are embittered, worried, dissatisfied with the measures being applied to the perpetrator.”(iDI-12)

“Policies need to have sustainability. For a policy to be sustainable, the prevention and protection project should not be a project. Measures and policies should not be project-based. They have to be permanent and the state has to ensure that, for the individual members of society, the resources needed to support them will always be available […].”(iDI-11)

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EU | European Union |

| NSI | National Statistical Institute |

| VAW | Violence against women |

Appendix A

| iDI 10—police officer, female, 41, conducted on 2 October 2024 iDI 11—police officer, female, 48, conducted on 10 October 2024 iDI 12—police officer, male, 42, conducted on 10 October 2024 iDI 13—prosecutor, male, 30, conducted on 14 October 2024 iDI 14—advisor to a minister, female, 48, conducted on 10 October 2024 iDI 20—NGO, male, 37, conducted on 13 August 2024 iDI 21—NGO, female, 52, conducted on 15 August 2024 iDI 22—judge, female, 42, conducted on 4 September 2024 iDI 23—NGO, female, 45, conducted on 12 September 2024 iDI 24—police officer, male, 46, conducted on 26 September 2024 iDI 30—NGO, female, 32, conducted on 19 August 2024 iDI 31—NGO, female, 30, conducted on 19 August 2024 iDI 32—state institution, female, 45, conducted on 20 August 2024 iDI 33—NGO, male, 61, conducted on 20 August 2024 iDI 34—state institution, female, 58, conducted on 03 October 2024 iDI 40—politician, female, 51, conducted 20 September 2024 iDI 41—international organization, female, 47, conducted on 25 September 2024 iDI 42—NGO, female, 40, conducted on 25 September 2024 iDI 43—NGO, female, 60, conducted on 27 September 2024 iDI 44—journalist, female, 35, conducted on 30 September 2024 iDI 45—politician, female, 47, conducted on 2 October 2024 iDI 50—lawyer, female, 45, conducted on 7 August 2024 iDI 51—investigator, female, 50, conducted 20 September 2024 iDI 52—judge, female, 45, conducted on 26 September 2024 iDI 53—prosecutor, female, 48, conducted on 16 October 2024 iDI 61—trade unionist, female, 59, conducted on 27 January 2025 |

Appendix B

| Focus group 1, two moderators, conducted on 11 September 2024 | Participant 1—prosecutor, female, 51 Participant 2—prosecutor, male, 39 Participant 3—police officer, female, 44 Participant 4—police officer, female, 42 Participant 5—police officer, male, 49 Participant 6—police officer, female, 49 Participant 7—prosecutor, female, 41 Participant 8—police officer, female, 52 Participant 9—prosecutor, male, 39 Participant 10—prosecutor, male, 42 Participant 11—police officer, male, 40 Participant 12—social worker, NGO, female, 52 Participant 13—social worker, NGO, female, 40 Participant 14—social worker, NGO, female, 44 |

| Focus group 2, two moderators, conducted on 11 September 2024 | Participant 1—police officer, female, 34 Participant 2—prosecutor, male, 35 Participant 3—prosecutor, female, 49 Participant 4—prosecutor, female, 44 Participant 5—investigator, female, 62 Participant 6—investigator, female, 48 Participant 7—police officer, male, 41 Participant 8—police officer, male, 45 Participant 9—police officer, male, 50 Participant 10—police officer, female, 52 Participant 11—social worker, NGO, female, 29 Participant 12—social worker, NGO, female, 48 Participant 13—social worker, NGO, female, 59 |

| Focus group 3, two moderators, conducted on 17 September 2024 | Participant 1—prosecutor, female, 43 Participant 3—judge, male, 34 Participant 4—social worker, NGO, female, 24 Participant 5—prosecutor, female, 31 Participant 6—police officer, male, 54 Participant 7—police officer, male 50 Participant 8—prosecutor, male, 30 Participant 10—social worker, Agency for Social Assistance, female, 45 Participant 11—social worker, NGO, female, 25 Participant 12—judge, female, 41 |

| Focus group 4, two moderators, conducted on 17 September 2024 | Participant 1—social worker, NGO, female, 25 Participant 2—social worker, NGO, female, 28 Participant 3—prosecutor, male, 40 Participant 4—prosecutor, male, 31 Participant 5—social worker, Agency for Social Assistance, female, 52 Participant 6—prosecutor, male, 35 |

| Focus group 5, two moderators, conducted on 18 September 2024 | Participant 1—social worker, NGO, female, 33 Participant 2—social worker, NGO, female, 47 Participant 5—social worker, Agency for Social Assistance, female, 60 Participant 6—prosecutor, female, 38 Participant 8—prosecutor, female, 44 Participant 9—prosecutor, female, 36 Participant 11—prosecutor, female, 40 Participant 12—police officer, male, 45 |

| Focus group 6, two moderators, conducted on 18 September 2024 | Participant 1—NGO, female, 40 Participant 2—judge, female, 38 Participant 4—police officer, female, 45 Participant 5—police officer, female, 56 Participant 6—NGO, female, 43 Participant 8—prosecutor, female, 42 Participant 9—prosecutor, male, 34 Participant 10—prosecutor, male, 30 Participant 11—police officer, female, 48 Participant 12—social worker, NGO, female, 36 Participant 13—social worker, NGO, female, 38 Participant 14—social worker, Agency for Social Assistance, female, 53 |

Appendix C

| Sample, Nationally Representative Survey | NSI, Population Census | |

|---|---|---|

| 18–24 years old | 9.1% | 6.9% |

| 25–29 years old | 5.4% | 5.6% |

| 30–39 years old | 19.7% | 15.4% |

| 40–49 years old | 16.1% | 18.0% |

| 50–59 years old | 21.5% | 17.2% |

| 60 years and older | 28.1% | 36.9% |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 49.8% | 47.4% |

| Female | 50.1% | 52.6% |

| Other | 0.1% | |

| Education: | ||

| Primary education | 8.8% | 19.0% |

| Secondary education (general and vocational) | 55.4% | 52.0% |

| Higher education | 35.5% | 29.0% |

| I don’t want to answer | 0.3% | |

| Place of residence | ||

| Capital | 19.7% | 18.5% |

| Regional city | 38.9% | 33.1% |

| Small town | 21.2% | 21.5% |

| Village | 20.2% | 26.8% |

| Region of a settlement | ||

| Blagoevgrad | 2.4% | 4.5% |

| Burgas | 5.1% | 5.8% |

| Varna | 6.5% | 6.6% |

| Veliko Tarnovo | 4.4% | 3.2% |

| Vidin | 1.1% | 1.2% |

| Vratsa | 2.7% | 2.3% |

| Gabrovo | 2.0% | 1.5% |

| Dobrich | 2.7% | 2.3% |

| Kardzhali | 2.5% | 2.2% |

| Kyustendil | 2.2% | 1.7% |

| Lovech | 2.6% | 1.8% |

| Montana | 2.2% | 1.9% |

| Pazardzhik | 1.7% | 3.5% |

| Pernik | 0.5% | 1.8% |

| Pleven | 4.4% | 3.5% |

| Plovdiv | 9.8% | 9.7% |

| Razgrad | 1.3% | 1.6% |

| Russe | 3.2% | 3.0% |

| Silistra | 2.7% | 1.5% |

| Sliven | 2.6% | 2.6% |

| Smolyan | 1.5% | 1.5% |

| Sofia-city | 19.7% | 19.4% |

| Sofia-area | 0.7% | 3.6% |

| Stara Zagora | 4.0% | 4.5% |

| Targovishte | 2.4% | 1.5% |

| Haskovo | 3.6% | 3.3% |

| Shumen | 3.2% | 2.3% |

| Yambol | 2.3% | 1.7% |

| 1 | In the text, we adopt the broader term violence against women, defined by the United Nations, as “any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.” (United Nations 1993, Art. 1). |

| 2 | In the period November 2021—February 2022, the NSI conducted a “Survey on Gender-Based Violence”. |

| 3 | By 2023, in order to be defined as a “domestic violence” there was a requirement for the act to be systematic, meaning it must have been committed at least three times. |

| 4 | The research project “Violence against Women: Typologies, Economic and Social Consequences” was implemented by research teams from the University of National and World Economy (base organization) through the Center for Sociological and Psychological Research at the Department of Economic Sociology, and Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski” (partner organization), through the Faculty of Economics, within the framework of the Competition for Funding of Fundamental Scientific Research—2023 of the Bulgarian National Science Fund (Grant agreement No КП-06-Н75/2 from 7 December 2023). |

| 5 | More about the characteristics of the so-called “chalga culture” (in Rice 2002; Statelova 2005; Sundal 2012; Nikolova 2012). |

References

- Alesina, Alberto, Benedetta Brioschi, and Eliana La Ferrara. 2021. Violence Against Women: A Cross-cultural Analysis for Africa. Economica 88: 70–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergvall, Sanna. 2024. Women’s economic empowerment and intimate partner violence. Journal of Public Economics 239: 105211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2021. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. London: SAGE Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, Linnea, Sofia Strid, and Hans Ekbrand. 2024. Men’s Economic Abuse Toward Women in Sweden: Findings from a National Survey. Violence Against Women 31: 2194–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- bTV News. 2025. “Not a Horror Movie, but a Terrifying Reality”: In 2024, 6400 Women Suffered from Domestic Violence. Available online: https://btvnovinite.bg/predavania/tazi-sutrin/ne-film-na-uzhasite-a-uzhasjavashta-realnost-prez-2024-g-6400-zheni-sa-postradali-ot-domashno-nasilie.html (accessed on 9 July 2025). (In Bulgarian).

- Capaldi, Deborah M., Naomi B. Knoble, Joann Wu Shortt, and Hyoun K. Kim. 2012. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse 3: 231–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, John W., and Vicki L. Plano Clark. 2007. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. 2014. Violence Against Women: Аn EU-Wide Survey. Available online: https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2014-vaw-survey-main-results-apr14_en.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Georgiev, Ivan. 2016. Some specific features of the judicial proceedings for protection from domestic violence. Contemporary law 27: 94–107. (In Bulgarian). [Google Scholar]

- Georgiev, Nikola. 2020. Domestic violence—Realities and forms of prevention. Knowledge: International Journal 41: 1057–63. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, Andrew, Kristin Dunkle, Leane Ramsoomar, Samantha Willan, Nwabisa Jama Shai, Sangeeta Chatterji, Ruchira Naved, and Rachel Jewkes. 2020. New learnings on drivers of men’s physical and/or sexual violence against their female partners, and women’s experiences of this, and the implications for prevention interventions. Global Health Action 13: 1739845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleva, Polya. 2019. Domestic violence—legal issues. Property and Law, 9. (In Bulgarian). [Google Scholar]

- González, Libertad, and Núria Rodríguez-Planas. 2020. Gender norms and intimate partner violence. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 178: 223–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, Lori. 1998. Violence Against Women: An Integrated, Ecological Framework. Violence Against Women 4: 262–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, Lori, and Andreas Kotsadam. 2015. Cross-national and multilevel correlates of partner violence: An analysis of data from population-based surveys. The Lancet Global Health 3: e332–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, Lori, Mary Ellsberg, and Megan Gottemoeller. 1999. Population Reports: Ending Violence Against Women. Baltimore: Center for Communication Programs, The Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health. Available online: https://vawnet.org/sites/default/files/assets/files/2016-10/PopulationReports.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Hristov, Atoni. 2022. Issues in the prevention of domestic violence. Law Journal of New Bulgarian University 17: 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewkes, Rachel. 2002. Intimate partner violence: Causes and prevention. Lancet 359: 1423–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Janet Elise, and Laura Brunell. 2006. The emergence of contrasting domestic violence regimes in post-communist Europe. Policy & Politics 34: 575–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katuli, Farida, and Godfrey Wandwi. 2025. Contribution of Information Communication Technology to the Prevention and Responsive to Gender Based Violence among Women and Children. Open Journal of Social Sciences 13: 111–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostadinova, Ralitsa. 2024. The reform of protection against domestic violence and Bulgarian criminal law. In The reform of Protection Against Domestic Violence: Collection of Reports from a Scientific and Applied Conference, 22.11.2023, Sofia Scientific and Applied Conference: The Reform of Protection Against Domestic Violence. Sofia: Institute of State and Law, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. (In Bulgarian) [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmanović, Tatjana, and Ana Pajvančić-Cizelj. 2018. Economic violence against women: Testimonies from the Women’s Court in Sarajevo. European Journal of Women’s Studies 27: 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LevFem. 2020. Opinion on the Draft National Strategy for Promoting Equality between Women and Men 2021–2030. Available online: https://levfem.org/blog/2020/11/16/stanovishte-strategia-2020/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Limantė, Agnė, Artūras Tereškinas, and Rūta Vaičiūnienė, eds. 2023. Gender-Based Violence and the Law: Global Perspectives and Eastern European Practices, 1st ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Makeva, Blagorodna. 2024. Domestic Violence in Bulgaria—Statistics and Facts. Legislation and Protection. NBU Law Journal XX 1: 95–114. (In Bulgarian). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannell, Jenevieve, Hattie Lowe, Laura Brown, Reshmi Mukerji, Delan Devakumar, Lu Gram, Henrica A. F. M. Jansen, Nicole Minckas, David Osrin, Audrey Prost, and et al. 2022. Risk factors for violence against women in high-prevalence settings: A mixed-methods systematic review and meta-synthesis. BMJ Global Health 7: e007704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Heredia, Nazaret, Gracia González-Gijón, Andrés Soriano Díaz, and Ana Amaro Agudo. 2021. Dating Violence: A Bibliometric Review of the Literature in Web of Science and Scopus. Social Sciences 10: 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Azorin, José. 2016. Mixed methods research: An opportunity to improve our studies and our research skills. European Journal of Management and Business Economics 25: 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Statistical Institute. 2022. EU-GBV Gender-Based Violence Survey, 2021. Available online: https://www.nsi.bg/press-release/izsledvane-na-nasilieto-osnovano-na-pol-eu-gbv-2021-6835?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- National Statistical Institute. 2024. Statistical Reference Book. Available online: https://www.nsi.bg/sites/default/files/files/publications/StatBook2024.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Nikolić-Ristanović, Vesna. 2002. Social Change, Gender and Violence: Post-communist and War Affected Societies. Dordrecht: Springer-Science+Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolova, Veneta. 2012. Silicone and Chalga Displace Traditional Values. Available online: https://bnr.bg/en/post/100155801/silicone-and-chalga-displace-traditional-values (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Oczkowska, Monika, Kajetan Trzcinski, and Michał Myck. 2024. Patterns of harassment and violence against women in Central and Eastern Europe: The role of the socio-economic context and gender norms in international comparisons. Baltic Journal of Economics 24: 261–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office for Health Improvement & Disparities. 2020. Mixed Methods Study. GOV.UK. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/mixed-methods-study (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Petrova, Krassimira, Velislava Chavdarova, and Daniela Tasevska. 2021. Research into the Ethnopsychological and Cultural Characteristics of the Bulgarian Family in the Context of Gender-Based Violence. Sofia: Faber. [Google Scholar]

- Petrunov, Georgi. 2014. Human trafficking in Eastern Europe: The case of Bulgaria. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 653: 162–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrunov, Georgi. 2023. Prostitution and Public Policy in Post-Socialist Bulgaria. Croatian Political Science Review/Politička Misao: Časopis za Politologiju 60: 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrunov, Georgi. 2024. Public Attitudes Towards Prostitution in Bulgaria in the Context of Social and Legal Neglection. Sociologija 66: 429–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philbrick, William C., John R. Milnor, Madhu Deshmukh, and Patricia N. Mechael. 2021. PROTOCOL: The use of information and communications technologies (ICT) for contributing to the prevention of, and response to, sexual and gender-based violence against women and children in lower- and middle-income countries: An evidence and gap map. Campbell Systematic Reviews 17: e1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prusik, Charles A. 2020. Adorno and Neoliberalism: The Critique of Exchange Society. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Rangelova, Rossitsa. 2024. Policies against domestic violence in a comparative international perspective and conclusions for Bulgaria. In The Reform for Protection from Domestic Violence. Sofia: Institute of State and Law, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, pp. 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, Timothy. 2002. Bulgaria or Chalgaria: The Attenuation of Bulgarian Nationalism in a Mass-Mediated Popular Music. Yearbook for Traditional Music 34: 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, Cynthia K. 2015. Economic abuse in the lives of women abused by an intimate partner: A qualitative study. Violence Against Women 21: 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, Amartya. 1995. Rationality and Social Choice. American Economic Review 85: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Shoaib, Muhammad, Muhammad Adnan Zaman, and Zaheer Abbas. 2024. Trends of Research Visualization of Gender Based Violence (GBV) from 1971–2020: A Bibliometric Analysis. Pakistan Journal of Law, Analysis and Wisdom 3: 203–16. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, Elizabeth, Alan Warde, and David Wright. 2008. Using Mixed Methods for Analysing Culture: The Cultural Capital and Social Exclusion Project. Cultural Sociology 3: 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statelova, Rosemary. 2005. The Seven Sins of Chalga: Toward an Anthropology of Ethnopop Music. Translated by Angela Rodel. Sofia: Prosveta. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, Erin, and Lori Heise. 2024. Women’s Economic Empowerment and Intimate Partner Violence: Untangling the Intersections. Spotlight Initiative and United Nations Development Programme. Available online: https://prevention-collaborative.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/WEE-Brief-2024-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Sundal, Kendra. 2012. The Development of Chalga: A Controversial Cultural Phenomenon in Modern Bulgaria. The Annual of Language & Politics and Politics of Identity 6: 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Todorova, Boryana. 2023. Her Goals are Quite Different. Strategies for Downplaying Violence against Women in Informal Discussions on the Internet. Balkanistic Forum 32: 165–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorova, Velina. 2022. Gender Wars in Bulgaria. In Family Matters: Essays in Honour of John Eekelaar. Edited by Jens Scherpe and Stephen Gilmore. Cambridge: Intersentia, pp. 245–62. [Google Scholar]

- Tur-Prats, Ana. 2019. Family Types and Intimate Partner Violence: A Historical Perspective. The Review of Economics and Statistics 101: 878–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tur-Prats, Ana. 2021. Unemployment and intimate partner violence: A Cultural approach. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 185: 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. 1993. Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/declaration-elimination-violence-against-women (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- United Nations. 2023. How Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence Impacts Women and Girls. Available online: https://unric.org/en/how-technology-facilitated-gender-based-violence-impacts-women-and-girls/ (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Valkova, Galya, and Mariya Doncheva. 2018. Protection from domestic violence—Practical problems in cases of acts of violence following an order issued under Art. 5, Para. 1 of the Protection from Domestic Violence Act. Lawyer’s Review, 3. Available online: https://www.sadebnopravo.bg/biblioteka/2019/2/13/-5-1- (accessed on 9 July 2025). (In Bulgarian).

- Velchev, Boris. 2019. The Crime Under Art. 144a of the Criminal Code. Modern Law, 2. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/72803931/ON_THE_CRIME_IN_ART_144a_OF_THE_CRIMINAL_CODE (accessed on 9 July 2025). (In Bulgarian).

- Wasileski, Gabriela, and Susan Miller. 2010. The Elephants in the Room: Ethnicity and Violence Against Women in Post-Communist Slovakia. Violence Against Women 16: 99–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Anaise, Lori Heise, Nancy Perrin, Colleen Stuart, and Michele R. Decker. 2024. Does going against the norm on women’s economic participation increase intimate partner violence risk? A cross-sectional, multi-national study. Global Health Research and Policy 9: 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank Group. 2024. Addressing Gender-Based Violence: 16 Days of Activism. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/gender/brief/addressing-gender-based-violence (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- World Health Organization. 2017. Violence Against Women. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- World Health Organization. 2021. Violence Against Women Prevalence Estimates, 2018: Global, Regional and National Prevalence Estimates for Intimate Partner Violence Against Women and Global and Regional Prevalence Estimates for Non-Partner Sexual Violence Against Women. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240022256 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Wu, Yanqi, Jie Chen, Hui Fang, and Yuehua Wan. 2020. Intimate Partner Violence: A Bibliometric Review of Literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 5607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlatanova, Valentina. 2001. Domestic Violence. Sofia: UniPress. (In Bulgarian) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petrunov, G. Cultural, Ideological and Structural Conditions Contributing to the Sustainability of Violence Against Women: The Case of Bulgaria. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 488. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080488

Petrunov G. Cultural, Ideological and Structural Conditions Contributing to the Sustainability of Violence Against Women: The Case of Bulgaria. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(8):488. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080488

Chicago/Turabian StylePetrunov, Georgi. 2025. "Cultural, Ideological and Structural Conditions Contributing to the Sustainability of Violence Against Women: The Case of Bulgaria" Social Sciences 14, no. 8: 488. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080488

APA StylePetrunov, G. (2025). Cultural, Ideological and Structural Conditions Contributing to the Sustainability of Violence Against Women: The Case of Bulgaria. Social Sciences, 14(8), 488. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080488