The Proximity of Hybrid Universities as a Key Factor for Rural Development

Abstract

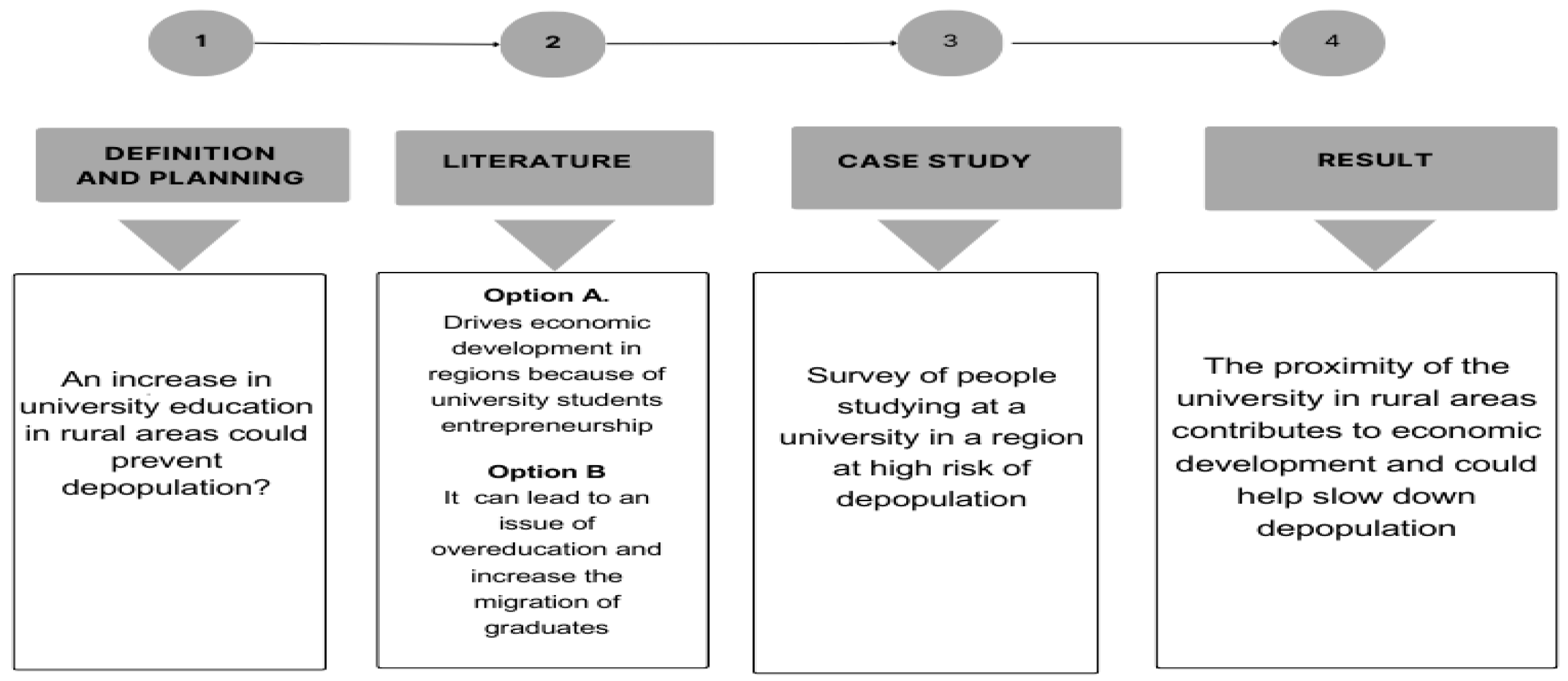

1. Introduction

- An increase in university education can slow down the process of depopulation.

- You could apply the acquired knowledge in a professional activity in your place of residence.

- There is a real concern about the problem of depopulation.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Migration of University Students

2.2. The Blended University Learning as a Driver for Rural Development

3. Case Study

3.1. Region of Castilla y León

3.2. The Universidad Nacional de Educacion a Distancia (UNED)

3.3. Sample Space and Analysis Method

4. Results

4.1. First Hypothesis: An Increase in University Education Can Slow Down the Process of Depopulation?

4.2. Second Hypothesis: You Could Apply the Acquired Knowledge in a Professional Activity in Your Place of Residence

Development of Professional Activity at the Place of Residence

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| No | 103 | 26.6% |

| Doubt | 105 | 27.2% |

| Yes | 178 | 46.1% |

| Total | 386 | 100% |

| Area of Study | Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Humanities area | No | 38 | 28.7% |

| Doubt | 37 | 28.0% | |

| Yes | 57 | 43.1% | |

| Total | 132 | 100% | |

| Science–Engineering | No | 31 | 26.5% |

| Doubt | 37 | 31.6% | |

| Yes | 49 | 41.8% | |

| Total | 117 | 100% | |

| Social Science and Law | No | 34 | 24.8% |

| Doubt | 31 | 22.6% | |

| Yes | 72 | 52.5% | |

| Total | 137 | 100% |

4.3. Third Hypothesis: There Is a Real Concern About the Problem of Depopulation

| Concern Depopulation | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Economic | 40.20% |

| Political | 65.80% |

| Real concern | 41.50% |

| Environmental awareness | 32.90% |

| Nostalgic and origins/others | 22.00% |

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Limitations and Further Lines of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UNED | Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia |

| MITECO | Ministerio para la Transición Ecologica y el Reto Demográfico |

| ESOMAR | European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research |

References

- Abramovsky, Laura, Rupert Harrison, and Helen Simpson. 2007. University Research and the Location of Business R&D. Economic Journal 117: 114–41. [Google Scholar]

- Agasisti, Tommaso, Cristian Barra, and Roberto Zotti. 2019. Research, Knowledge Transfer, and Innovation: The Effect of Italian Universities’ Efficiency on Local Economic Development 2006–2012. Journal of Regional Science 59: 819–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlin, Lina, Martin Andersson, and Per Thulin. 2018. Human Capital Sorting: The “When” and “Who” of the Sorting of Educated Workers to Urban Regions. Journal of Regional Science 58: 581–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamá-Sabater, Luisa, Vicente Budí, Norat Roig-Tierno, and José María García-Álvarez-Coque. 2021. Drivers of Depopulation and Spatial Interdependence in a Regional Context. Cities 114: 103217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarco, J. Jhonnel, and Esmilsinia V. Álvarez-Andrade. 2012. Google Docs: Una alternativa de encuestas online. Educación Médica 15: 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albulescu, Ion, and Mirela Albulescu. 2014. The University in the Community. The University’s Contribution to Local and Regional Development by Providing Educational Services for Adults. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 142: 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Andersson, Roland, John M. Quigley, and Mats Wilhelmsson. 2009. Urbanization, productivity, and innovation: Evidence from investment. Journal of Urban Economics 66: 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, Luc, Attila Vargas, and Acs Zoltan. 1997. Local Geographic Spillovers between University Research and High Technology Innovations. Journal of Urban Economics 41: 422–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artz, Georgeanne. 2003. Rural Area Brain Drain: Is It a Reality? Choices American Agricultural Economics Association 18: 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Banco de España. 2020. La Distribución espacial de la población en España y sus implicaciones económicas. Available online: https://www.bde.es/f/webbde/SES/Secciones/Publicaciones/PublicacionesAnuales/InformesAnuales/20/Fich/InfAnual_2020-Cap4.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Baraja-Rodríguez, Eugenio, Daniel Herrero-Luque, and Marta Martínez-Arnáiz. 2021. Política Agraria Común y despoblación en los territorios de la España interior (Castilla y León). AGER Revista de Estudios sobre Despoblación y Desarrollo Rural 33: 151–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardales-Cárdenas, Miguel, Edgard Francisco Cervantes-Ramón, Iris Katherine Gonzales-Figueroa, and Lizet Malena Farro-Ruiz. 2024. Entrepreneurship Skills in University Students to Improve Local Economic Development. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 13: 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berck, Peter, Sofia Tano, and Olle Westerlund. 2016. Regional Sorting of Human Capital: The Choice of Location among Young Adults in Sweden. Regional Studies 50: 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, Aude, and Martin Bell. 2018. Educational Selectivity of Internal Migrants: A Global Assessment. Demographic Research 39: 835–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, Christopher R., and Edward L. Glaeser. 2005. The Divergence of Human Capital Levels across Cities. Papers in Regional Science 84: 407–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BOCYL. 2023. Boletín Oficial de Castilla y León. Available online: https://bocyl.jcyl.es/boletin.do?fechaBoletin=24/10/2023 (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Borén, Thomas, and Craig Young. 2013. The Migration Dynamics of the “Creative Class”: Evidence from a Study of Artists in Stockholm, Sweden. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 103: 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, Pilar, and Arantza del Valle. 2010. Older people as actors in the rural community innovation and empowerment. Athenea Digital 17: 171–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, Allison, and David A. Wolfe. 2008. Universities and Regional Economic Development: The Entrepreneurial University of Waterloo. Research Policy 37: 1175–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, Oliver, and Benjamin Weigert. 2010. Where Have All the Graduates Gone? Internal Cross-State Migration of Graduates in Germany 1984–2004. The Annals of Regional Science 44: 559–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchel, Felix, and Maarten van Ham. 2003. Overeducation, Regional Labor Markets, and Spatial Flexibility. Journal of Urban Economics 53: 482–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capsada-Munsech, Queralt. 2017. Overeducation: Concept, Theories, and Empirical Evidence. Sociology Compass 11: e12518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuano, Stella. 2012. The South-North Mobility of Italian College Graduates. An Empirical Analysis. European Sociological Review 28: 538–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CESCYL. 2023. Observatorio de Emancipación del 2o semestre de 2023. Available online: https://www.cescyl.es/es/actualidad/noticias-ces/observatorio-emancipacion-2-semestre-2023 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Conejos, Alberto. 2019. Un estudio sobre la juventud rural en la provincia de Zaragoza. In Cátedra DPZ. Zaragoza: Universidad de Zaragoza. Available online: http://catedradespoblaciondpz.unizar.es/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Informe_Catedra_-2020-1_Conejos.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Crown, Daniel, Masood Gheasi, and Alessandra Faggian. 2020. Interregional Mobility and the Personality Traits of Migrants. Papers in Regional Science 99: 899–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaVanzo, Julie. 1983. Repeat Migration in the United States: Who Moves Back and Who Moves On? The Review of Economics and Statistics 65: 552–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Roca, Jorge. 2017. Selection in Initial and Return Migration: Evidence from Moves across Spanish Cities. Journal of Urban Economics 100: 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, José María. 2018. Más allá del tópico de la España vacía: Una geografía de la despoblación. In Informe España 2018. Madrid: UniversidadPontificia-Comillas, pp. 233–95. Available online: https://blogs.comillas.edu/informeespana/informe-espana-2018 (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Di Liberto, Adriana. 2008. Education and Italian Regional Development. Economics of Education Review 27: 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Modino, José Manuel, and Ana Pardo-Fanjul. 2020. Despoblación, envejecimiento y políticas sociales en Castilla y León. Revista Galega de Economía 29: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docquier, Frédéric, and Hillel Rapoport. 2012. Globalization, Brain Drain, and Development. Journal of Economic Literature 50: 681–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2010. A European Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eu2020/pdf/COMPLET%20EN%20BARROSO%20%20%20007%20-%20Europe%202020%20-%20EN%20version.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- European Commission. Joint Research Centre. 2018. Territorial Facts and Trends in the EU Rural Areas Within 2015–2030. Luxembourg: Publications Office. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/525571 (accessed on 19 December 2023).

- European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research. 2012. Guía para la Investigación Online. World Research Codes and Guidelines. Amsterdam: ESOMAR. [Google Scholar]

- European Union-Regional Policy. 2011. Connecting Universities to Regional Growth: A Practical Guide. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/presenta/universities2011/universities2011_en.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- EURYDICE. 2001. National Actions to Implement Lifelong in Europe. Brussels: Ministerio de Educación. [Google Scholar]

- Faggian, Alessandra, and Philip McCann. 2008. Human Capital, Graduate Migration and Innovation in British Regions. Cambridge Journal of Economics 33: 317–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggian, Alessandra, and Philip McCann. 2009. Universities, Agglomerations and Graduate Human Capital Mobility. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 100: 210–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggian, Alessandra, Mark Partridge, and Edward Malecki. 2017. Creating an Environment for Economic Growth: Creativity, Entrepreneurship or Human Capital? International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 41: 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggian, Alessandra, Philip McCann, and Stephen Sheppard. 2006. An Analysis of Ethnic Differences in UK Graduate Migration Behaviour. The Annals of Regional Science 40: 461–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggian, Alessandra, Roberta Comunian, and Qian Cher Li. 2014. Interregional Migration of Human Creative Capital: The Case of “Bohemian Graduates”. Geoforum 55: 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlay, Allan, David McCollum, Rory Coulter, and Vernon Gayle. 2015. New Mobilities Across the Life Course: A Framework for Analysing Demographically Linked Drivers of Migration. Population, Space and Place 21: 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florax, Raymond J. G. M. 1992. The University: A Regional Booster? Economic Impacts of Academic. Knowledge Infrastructure. Aldershot: Avebury. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, Richard. 2002. The Rise of the Creative Class. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, Richard, Charlotta Mellander, and Kevin Stolarick. 2008. Inside the Black Box of Regional Development--Human Capital, the Creative Class and Tolerance. Journal of Economic Geography 8: 615–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Masahisa. 1988. A Monopolistic Competition Model of Spatial Agglomeration. Regional Science and Urban Economics 18: 87–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cuesta, Sara, Milagros Sáinz-Ibañez, and Pablo Martín-Pulido. 2003. La UNED en Castilla y León: Un estudio desde la perspectiva de género. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia 6: 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, Edward Ludwing, and David Christopher Maré. 2001. Cities and Skills. Journal of Labor Economics 19: 316–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Blanco, María, María Esther Oliverira, and Antonio Rodríguez. 2024. Democratizacion del Conocimiento. Un seminario del program universitario a las personas mayors del mundo rural. Revista Boletín REPIDE 13: 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Leonardo, Miguel, and Antonio López-Gay. 2019. Emigración y fuga de talento en Castilla y León. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles 80: 2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Leonardo, Miguel, and Antonio López-Gay. 2021. Del éxodo rural al éxodo interurbano de titulados universitarios: La segunda oleada de despoblación. AGER Revista de Estudios sobre Despoblación y Desarrollo Rural 31: 7–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, Paul D., and George Joseph. 2006. College to Work Migration of Technology Graduates and Holders of Doctorates Within the United States. Journal of Regional Science 46: 627–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, Philip E. 1980. Migration and Climate. Journal of Regional Science 20: 227–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodzicki, Tomasz, and Mateusz Jankiewicz. 2022. The Role of the Common Agricultural Policy in Contributing to Jobs and Growth in EU’s Rural Areas and the Impact of Employment on Shaping Rural Development: Evidence from the Baltic States. Editado por Wujun Ma. PLoS ONE 17: e0262673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, Eduardo, Enrique Moral-Benito, and Roberto Ramos. 2020. The Spatial Distribution of Population in Spain. Anomaly in European Perspective. Banco de España. Available online: https://www.bde.es/f/webbde/SES/Secciones/Publicaciones/PublicacionesSeriadas/DocumentosTrabajo/20/Files/dt2028e.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Haapanen, Mika, and Hannu Tervo. 2012. Migration of the Highly Educated: Evidence from Residence Spells of University Graduates. Journal of Regional Science 52: 587–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harloe, Michael, and Beth Perry. 2004. Universities, Localities and Regional Development: The Emergence of the ‘Mode 2’ University? International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 28: 212–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Idárraga, Paula, Enrique López-Bazo, and Elisabet Motellón. 2012. Informality and Overeducation in the Labor Market of a Developing Country. IDEAS Working Paper Series from RePEC. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/working-papers/informality-overeducation-labor-market-developing/docview/1698192058/se-2 (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Hicks, John. Richard. 1963. The Theory of Wages, 2nd ed. Toronto: Palgrave McMillan. Available online: http://pombo.free.fr/hickswages.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Jauhiainen, Signe. 2011. Overeducation in the Finnish Regional Labour Markets. Papers in Regional Science 90: 573–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Kenneth M., and Daniel T. Lichter. 2019. Rural Depopulation: Growth and Decline Processes over the Past Century. Rural Sociology 84: 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leduc, Gaëlle, Gordana Manevska-Tasevska, Helena Hansson, Marie Arndt, Zoltán Bakucs, Michael Böhm, Mihai Chitea, Violeta Florian, Lucian Luca, Anna Martikainen, and et al. 2021. How Are Ecological Approaches Justified in European Rural Development Policy? Evidence from a Content Analysis of CAP and Rural Development Discourses. Journal of Rural Studies 86: 611–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesser, Virginia M., and Lydia D. Newton. 2016. Mixed-mode Surveys Compared with Single Mode Surveys: Trends in Responses and Methods to Improve Completion. Journal of Rural Social Sciences 31: 7–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lovén, Ida, Cecilia Hammarlund, and Martin Nordin. 2020. Staying or Leaving? The Effects of University Availability on Educational Choices and Rural Depopulation. Papers in Regional Science 99: 1339–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Roldán, Pedro, and Sandra Fachelli. 2015. Metodología de la Investigación Social Cuantitativa. Bellaterra (Cerdanyola del Vallés): Dipósit Digital de Documents. Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona. Available online: https://ddd.uab.cat/pub/caplli/2016/163564/metinvsoccua_a2016_cap1-2.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Machin, Stephen, and Kjell Gunnar Salvanes. 2025. Education and Mobility. Journal of the European Economic Association 10: 417–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleszyk, Piotr. 2021. Outflow of Talents or Exodus? Evidence on youth emigration from EU’s peripheral areas. REGION 8: 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Männasoo, Kadri, Heili Hein, and Raul Ruubel. 2018. The Contributions of Human Capital, R&D Spending and Convergence to Total Factor Productivity Growth. Regional Studies 52: 1598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messer, Benjamin L., and Don A. Dillman. 2011. Surveying the General Public over the Internet Using Address-Based Sampling and Mail Contact Procedures. Public Opinion Quarterly 75: 429–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, Morga M., and Don A. Dillman. 2011. Improving Response to Web and Mixed-Mode Surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly 75: 249–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio para la Transformación Ecológica y Reto Demográfico. 2021. 130 Medidas frente al reto demográfico. MITECO. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/reto-demografico/temas/medidas-reto-demografico.html (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Molina Ibáñez, Mercedes, Luis Camarero Rioja, José María Sumpsi Viñas, Isabel Bardaji Azcárate, and Rocío Pérez Campaña. 2023. El proceso de despoblación: Desequilibrios e inequidades sociales. El tiempo de las políticas públicas. In Despoblación, cohesión territorial e igualdad de derechos. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Políticos y Constitucionales, pp. 15–81. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, Kevin M., Andrei Shleifer, and Robert W. Vishny. 1991. The Allocation of Talent: Implications for Growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 106: 503–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumark, David, and Helen Simpson. 2015. Place-Based Policies. In Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics. Amsterdam: Elsevier, vol. 5, pp. 1197–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, Jacobo, and Antonio Sendín. 2023. Consideraciones Estadísticas y Sociológicas Dirigidas al Desarrollo de la Comarca de Sayago (Zamora-España). AGER Revista de Estudios sobre Despoblación y Desarrollo Rural 38: 144–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olejnik, Alicja. 2008. Using the Spatial Autoregressively Distributed Lag Model in Assessing the RegionalConvergence of Per-capita Income in the EU25. Papers in Regional Science 87: 371–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, João, and Miguel St. Aubyn. 2009. What Level of Education Matters Most for Growth? Evidence from Portugal. Economics of Education Review 28: 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, Luis Antonio Sáez. 2021. Análisis de la Estrategia Nacional frente a la Despoblación en el Reto Demográfico en España. AGER Revista de Estudios sobre Despoblación y Desarrollo Rural 33: 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Juste, Ramón. 1999. Veinticinco años de la UNED. Madrid: UNED. [Google Scholar]

- Pinilla, Vicente, and Luis-Antonio Sáez. 2017. La Despoblación Rural en España: Génesis de un Problema y Políticas Innovadoras: Informes CEDDAR 2017-2. Zaragoza: Centro de Estudios sobre Despoblación y Desarrollo en ÁreasRurales. Available online: https://www.roldedeestudiosaragoneses.org/wp-content/uploads/Informes-2017-2-Informe-SSPA1_2017_2.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Pinilla, Vicente, and Luis-Antonio Sáez. 2021. What Do Public Policies Teach Us About Rural Depopulation: The Case Study of Spain. European Countryside 13: 330–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psycharis, Yannis, Vassilis Tselios, and Panagiotis Pantazis. 2019. Interregional student migration in Greece:patterns and determinants. Revue d’Économie Régionale & Urbaine 4: 781–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, Raul, Jordi Suriñach, and Manuel Artís. 2010. Human Capital Spillovers, Productivity and Regional Convergence in Spain. Papers in Regional Science 89: 435–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, Raul, Jordi Surinach, and Manuel Artís. 2012. Regional Economic Growth and Human Capital: The Role of Over-Education. Regional Studies 46: 1389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehak, Stefan. 2020. Regional Dimensions of Human Capital and Economic Growth: A Review of Empirical Research. Scientific Papers of the University of Pardubice, Series D: Faculty of Economics and Administration 28: 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson-Pant, Anna. 2023. Education for Rural Development: Forty Years On. International Journal of Educational Development 96: 102702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, Andrés, and Montserrat Vilalta-Bufí. 2005. Education, Migration, and Job Satisfaction: The Regional Returns of Human Capital in the EU. Journal of Economic Geography 5: 545–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, Stuart S., and William C. Strange. 2008. The Attenuation of Human Capital Spillovers. Journal of Urban Economics 64: 373–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabrina, Tomasi, Cavicchi Alessio, Aleffi Chiara, Paviotti Gigliola, Ferrara Concetta, Baldoni Federica, and Passarini Paolo. 2021. Civic Universities and Bottom-up Approaches to Boost Local Development of Rural Areas: The Case of the University of Macerata. Agricultural and Food Economics 9: 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San-Martín González, Enrique, and Federico Soler-Vaya. 2024. Depopulation Determinants of Small Rural Municipalities in the Valencia Region (Spain). Journal of Rural Studies 110: 103369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjaastad, Larry A. 1962. The Costs and Returns of Human Migration. Journal of Political Economy 70: 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skuras, Dimitris, Nicolas Meccheri, Manuel Belo-Moreira, Jordi Rosell, and Sophia Stathopoulou. 2005. Entrepreneurial Human Capital Accumulation and the Growth of Rural Businesses: A Four-Country Survey in Mountainous and Lagging Areas of the European Union. Journal of Rural Studies 21: 67–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerfield, Fraser, and Ioannis Theodossiou. 2017. The Effects of Macroeconomic Conditions at graduation on overeducation. Economic Inquiry 55: 1370–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terluin, Ida J. 2003. Differences in Economic Development in Rural Regions of Advanced Countries: An Overview and Critical Analysis of Theories. Journal of Rural Studies 19: 327–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosi, Francesca, Roberto Impicciatore, and Rosella Rettaroli. 2019. Individual Skills and Student Mobility in Italy: A Regional Perspective. Regional Studies 53: 1099–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turmo-Garuz, Joaquin, M.-Teresa Bartual-Figueras, and Francisco-Javier Sierra-Martinez. 2019. Factors Associated with Overeducation Among Recent Graduates During Labour Market Integration: The Case of Catalonia (Spain). Social Indicators Research 144: 1273–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, Anna, and John Van Reenen. 2019. The Economic Impact of Universities: Evidence from across the Globe. Economics of Education Review 68: 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Werfhorst, Herman G. 2002. A Detailed Examination of the Role of Education in Intergenerational Social-Class Mobility. Social Science Information 41: 407–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, Attila. 2000. Local Academic Knowledge Transfers and the Concentration of Economic Activity. Journal of Regional Science 40: 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venhorst, Viktor, Jouke Van Dijk, and Leo Van Wissen. 2011. An Analysis of Trends in Spatial Mobility of Dutch Graduates. Spatial Economic Analysis 6: 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, Johanna. 2015. The Two Faces of R&D and Human Capital: Evidence from Western European Regions. Papers in Regional Science 94: 525–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, John V. 2018. Do Higher College Graduation Rates Increase Local Education Levels? Papers in Regional Science 97: 617–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Categories | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased training prevents depopulation | Yes | 227 | 58.80% | |

| No | 159 | 41.20% | ||

| Age | Between 18 and 39 years | 185 | 47.90% | |

| Between 40 and 59 years | 180 | 46.60% | ||

| 60 years or more | 21 | 5.40% | ||

| Sex | Man | 164 | 43% | |

| Woman | 222 | 57% | ||

| Labor activity | Yes | 288 | 74.60% | |

| No | 98 | 25.40% | ||

| Causes of depopulation: | ||||

| Lack of job opportunities | Yes | 350 | 90.70% | |

| No | 36 | 9.30% | ||

| Lack of infrastructure | Yes | 306 | 79.30% | |

| No | 80 | 20.70% | ||

| Lack of social services | Yes | 324 | 83.90% | |

| No | 62 | 16.10% | ||

| Lack of leisure | Yes | 230 | 59.60% | |

| No | 156 | 40.40% | ||

| Ageing population | Yes | 284 | 73.60% | |

| No | 102 | 26.40% | ||

| Interest perception (index) | Low or none | 45 | 11.70% | |

| Medium | 201 | 52.10% | ||

| High | 140 | 36.30% | ||

| Variable | Cramer’s Phi/V | Odds Ratio | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.138 * | N.A. | There are differences between Age: higher prevalence among those between 40 and 59 years old. |

| Sex | 0.034 | 1.15 | There are no significant differences between men and women. |

| Labor activity | 0.02 | 1.1 | There are no significant differences if you work. |

| Undertaking the End-of-Degree Project | 0.250 *** | 2.87 | There are differences between those who have considered the possibility of directing their end-of-study work towards some activity that can be carried out in rural areas and those who have not. Higher prevalence in those who can guide you. |

| Lack of job opportunities | 0.184 *** | 3.66 | There are differences between those who believe that one of the reasons is the scarcity of job opportunities. Higher prevalence among those who consider that job opportunities are lacking. |

| Lack of infrastructure | 0.208 *** | 2.86 | There are differences between those who believe that one of the reasons is the lack of labor infrastructure. Higher prevalence among those who say there is a lack of infrastructure. |

| Lack of social services | 0.136 *** | 2.09 | There are differences between those who believe that one of the reasons is the lack of social services. Higher prevalence among those who say that social services are lacking. |

| lack of leisure | 0.062 | 1.29 | There are no differences between those who consider that the cause is because there is a shortage of leisure and those who think that it is not. |

| Population aging | 0.155 ** | 2.02 | There are differences between those who believe that one of the reasons is the aging of the population and those who do not. Greater prevalence among those who think that it is a reason. |

| Interest perception (index) | 0.129 * | N.A. | There are differences between the level of interest in unpopulated areas, with a higher prevalence among those who consider that interest is low or null. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Núñez-Martínez, J.; Rodríguez-Fernández, L.; Rodríguez, L.F. The Proximity of Hybrid Universities as a Key Factor for Rural Development. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080467

Núñez-Martínez J, Rodríguez-Fernández L, Rodríguez LF. The Proximity of Hybrid Universities as a Key Factor for Rural Development. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(8):467. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080467

Chicago/Turabian StyleNúñez-Martínez, Jacobo, Laura Rodríguez-Fernández, and Luisa Fernanda Rodríguez. 2025. "The Proximity of Hybrid Universities as a Key Factor for Rural Development" Social Sciences 14, no. 8: 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080467

APA StyleNúñez-Martínez, J., Rodríguez-Fernández, L., & Rodríguez, L. F. (2025). The Proximity of Hybrid Universities as a Key Factor for Rural Development. Social Sciences, 14(8), 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080467