1. Introduction

Posters are more than mere advertisements aimed at promoting a product; they are cultural artifacts and commodities and are often claimed to hold a visible and meaningful place in the social and personal lives of individuals and communities. As paratexts, media posters serve as extensions of and connections to broader media products, such as films, television shows, and games, while also operating as independent cultural artifacts (

Gray 2010;

Freeman 2017). Hence, media posters “play a key role in outlining a show’s genre, its star intertexts, and the type of world a would-be audience member is entering,” functioning much like other cultural objects (

Gray 2010, p. 52). They contribute to the completion, enrichment, or enhancement of the media experience through the incorporation of synergistic visual and textual elements (

Gray 2010, pp. 6–7).

Wang (

2019, p. 423) further asserts that “the movie poster determines the success of the film to a certain extent,” underscoring its relevance in shaping audience engagement. Posters offer distinct dimensions of media interaction, exemplified by the existence of two main types: physical and digital. Physical posters have historically been used in public spaces as advertisements, appearing in cinemas, on billboards, and across public transport (

Frost et al. 2006, p. 21), and are often sold as merchandise to be displayed in private settings. The price of physical posters, however, varies significantly depending on the seller, material, collectability, and other value-enhancing features. By way of contrast, digital posters have risen to prominence in the internet age and are typically promoted by media companies through social media platforms and used by consumers as wallpapers on computers and smartphones. Both physical and digital posters are generally affordable, with digital posters frequently accessible for free or via specialized poster platforms such as PosterSpy.

Posters, whether digital or physical in form, may be categorized as either official, produced by studios primarily for marketing purposes, or unofficial, often fan-created artworks referred to as ‘fan art’. Media posters thus function simultaneously as advertisements and commodities, transforming intangible media texts into tangible cultural products (

Gray 2010, p. 6). As

Meng and Shen (

2021) argue, posters possess value that extends beyond their commercial and utilitarian purposes, encompassing cultural, artistic, and symbolic significance. This density of meaning stems from the necessity for a poster to convey the core themes, mood, and identity of a media text through a single, static, two-dimensional image. The Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) describes posters as “a vital means of communication” (

Victoria and Albert Museum 2021), and

Isfandiyary (

2017),

Case (

2009),

Wang (

2019),

Chunyuan and Li (

2021), and

Chen and Gao (

2013) all support the view that posters communicate a wide range of messages, spanning commercial and political to cultural and personal. The

Victoria and Albert Museum (

2021) notes that posters have promoted everything from products and performances to political causes and social movements, making them “compelling visual evidence of our social and cultural history”.

Case (

2009) adds that posters can also act as deeply personal objects, expressing individual identity, taste, and interest.

In the realm of visual media such as film and TV, posters often serve as the first point of engagement between a viewer and a media text, offering a condensed visual narrative (

24×36: A Movie About Movie Posters 2016;

Wang 2019;

Meng and Shen 2021;

Chunyuan and Li 2021).

Wang (

2019, p. 423) notes that “the main purpose of poster design is to convey the theme and content of the film, as well as to promote important information.” This is exemplified in the iconic

Jaws (1975) poster by Roger Kastel, which features a massive shark emerging from the ocean, mouth agape, beneath an unsuspecting swimmer. The bold, red colored used for the title and limited yet impactful iconography convey the film’s themes of suspense, terror, and isolation with striking clarity (

Rhodes and Singer 2024;

IMDb 2024). In the 1950s, due to limited special effects budgets, film posters became an essential tool for capturing the public’s imagination, often surpassing the films themselves in quality.

In the absence of sophisticated on-screen visuals, audiences were required to rely heavily on their imagination to bridge the gap between the promise of the poster and the reality of the film.

Rhodes and Singer (

2024) claim that such posters can be “remembered even without having seen the movie,” because they “signify and induce expectations and desire,” creating intrigue independently of the film itself. Hence, media posters represent a unique form of engagement with an audience and are thus an extension of the media text and a standalone cultural artifact. With the rise in digital technologies and the refinement of visual effects, contemporary media texts now frequently match, or even surpass, the visual quality promised by their promotional materials. This shift underscores the evolving role of posters in media culture, as unlike other forms of merchandise, such as action figures, posters offer the first visual impression of a media text. They provide a distilled and stylized representation of richly imagined worlds, acting as both a marketing tool and a narrative gateway.

While their primary function has historically been commercial, designed to help sell the media text, many individuals own and display media posters within their personal spaces. As noted by

Dawsons Auctions (

2024), “posters for movies are also among the most actively collected, representing a simple way to show off your love of both cinema and art”, especially when compared to other forms of fan merchandise As

Appadurai (

1986, p. 5) notes, cultural objects become meaningful through the human actors, be they companies, fans, or collectors, who encode significance into their forms, uses, and trajectories.

Gray (

2010, p. 52) similarly emphasizes that posters are “densely packed with meaning” by their creators, making them ideal for investigating how intended meanings intersect with personal interpretations and uses. However, despite this apparent richness and importance of media posters, there is a relative absence of published studies which explore the potential significances and meanings they hold for their owners. This is perhaps surprising given the importance of film and TV media in society as asserted by Marshall McLuhan—“the key factors that determine the social form of human history are not politics, economy and culture but media” (

Chunyuan and Li 2021, p. 1).

There is clearly much scope for research here into the inter-relationships between media posters and their owners, but, of course, there are many genres of entertainment in the movie and TV spheres and addressing all of them would be an enormous challenge. Hence, the focus of the research set out in this paper was specifically on posters linked to science fiction and fantasy movies and TV shows. These two genres are related but also different and were selected over other media genres primarily because they offer a vast imaginative landscape populated by diverse worlds, environments, and characters. These genres provide a unique capacity for transcending the limitations of time and space, inviting viewers to envision realities that are both different from and reflective of our own. As such, they serve not only as visual artifacts but also as portals into alternative realms, making them particularly compelling for exploring questions of meaning, identity, and emotional engagement. Renowned science fiction writer Ray Bradbury famously emphasized the significance of the genre as “the most important literature in the history of the world, because it’s the history of ideas, the history of our civilization birthing itself. ...Science fiction is central to everything we’ve ever done, and people who make fun of science fiction writers don’t know what they’re talking about.” (

Olympia Publishers 2024).

Fantasy is the older of the two genres, with its roots tracing back to the pre-modern world of myth and religion. It has historically served as a symbolic means of articulating universal human challenges, such as birth and death, often through the representation of gods and mythical figures (

Blum 2011).

Mathews (

2002, p. 2) defines fantasy as “a fiction that elicits wonder through elements of the supernatural or impossible. It consciously breaks free from mundane reality”. Similarly,

Lynn (

1983, p. ix) suggests that “fantasy deals with the impossible and the inexplicable” and primarily incorporates supernatural elements such as magic.

Roberts (

2000, p. 1), states that “science fiction as a genre or division of literature distinguishes its fictional worlds to one degree or another from the world in which we live: a fiction of the imagination rather than observed reality, a fantastic literature”. Bradbury goes much further and asserts that “A science fiction story is just an attempt to solve a problem that exists in the world, sometimes a moral problem, sometimes a physical or social or theological problem.” (

Bradbury 2004, p. 108). Recent scholarship challenges this over-simplified divide between science fiction and fantasy.

Rieder (

2010) argues that genre definitions depend more on historical and institutional contexts than fixed traits, while

Canavan and Link (

2019) frame SF as a contested category. While both science fiction and fantasy (SFF) originated in literary forms such as books and magazines, they have since flourished in visual media, becoming a dominant force in contemporary entertainment (

Broderick 2003, p. 59). Once regarded as a marginal or ‘B-movie’ genre in the United States during the 1950s (

Schauer 2017), science fiction in particular began to gain mainstream popularity in the 1980s, marked by the success of blockbuster films such as

Star Wars (1977) and

Back to the Future (1985) (

The Numbers 2024a,

2024b), and this has continued into the present day. For example, as of 2020, the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU), comprising 23 films, had collectively grossed USD 22,590,455,007 worldwide, making it the highest-grossing film franchise in history (

The Numbers 2020). These examples underscore the growing cultural and economic significance of the SFF genres. This shift is largely attributable to technological advancements, such as the use of computer-generated imagery (CGI), which have enabled the visualization of fantastical worlds with a level of realism that was previously unattainable (

Prince 2002;

Chunyuan and Li 2021).

While previous studies have explored the marketing or esthetic functions of film posters through textual and visual analysis, few have examined how fans and owners themselves interpret, display, and attribute meaning to these artifacts. This study distinguishes itself by focusing on the lived experiences of poster owners’, using survey and interview data to analyze how posters function as tools of emotional connection, personal expression, and fan identity. As such, the work expands on studies like

Chen and Gao (

2013), which emphasize content analysis, by centering the voice of the audience as meaning-makers. The research reported here aimed to understand the inter-relationships that owners have with their posters. As noted above, this is a relatively underexplored area of social life, and this paper will serve to be a lens through which to examine the broader world of fandoms and posters as cultural artifacts and potential sources of significance and meaning to owners. This study adopts a cultural sociological approach to “meaning” and “significance,” drawing on theories of material culture and identity (

Belk 1988;

Appadurai 1986). In this context, meaning is understood as the subjective, emotional, and symbolic value ascribed to posters by their owners, while significance refers to their perceived relevance in shaping self-expression, esthetic preferences, and personal or social identities. The research sought to address questions such as whether these posters simply serve as decorative windows into fantastical realms or do they carry deeper cultural significance and meaning for their owners. If so, what are these meanings, and how do they manifest in the everyday lives of poster owners? Do the posters reflect the values, behavior, identity, sense of self, emotional well-being, and self-expression of their owners? There is much theory that can be drawn on here. For example, do SFF media posters serve as a “different mode of self-presentation” (

McVeigh 2000, p. 225), reflecting their owners’ interests and identities? This aligns with

Tilley’s (

1999, p. 76) claim that “things create people as much as people make them,”

Belk’s (

1988, p. 139) view that possessions shape identity, and

Jenkins’ (

1992) argument that fan engagement with media objects plays a central role in expressing and constructing identity. Myths, and, by extension, media narratives, are said to offer frameworks for understanding and navigating life’s challenges (

Campbell and Moyers 1991), and

Kadyrgali et al. (

2024) suggest that “emotion is the most vital factor” connecting audiences to media texts. This all resonates with

Smith’s (

2022) assertion that narratives elicit specific feelings and experiences, which could be extended to posters as visual extensions of those texts.

This research was based on data collected through an online survey and a follow-up set of semi-structured interviews that took place between 2020 and 2022, a period that spanned the COVID-19 pandemic and its immediate aftermath. Respondents were mostly from the Western world context, but it is important to note that this focus refers to where the respondents were primarily located and does not reflect the geographical origin of the media texts or the posters themselves. The following section sets out the materials and methods for data collection and analysis, and this is followed by a presentation of the online survey results. The paper then moves on to a discussion of these results and how they were subsequently explored in the interviews, and how they related to wider literature. The final section of the paper sets out some key conclusions that emerged.

4. Discussion

In this study, “culture” refers to the shared meanings, practices, and values associated with fandom communities, while “fan culture” is understood as the collective identity and engagement practices through which individuals connect over science-fiction and fantasy media. While the survey focused on personal meanings, the interviews revealed how these are shaped by broader cultural narratives and fan-based interactions.

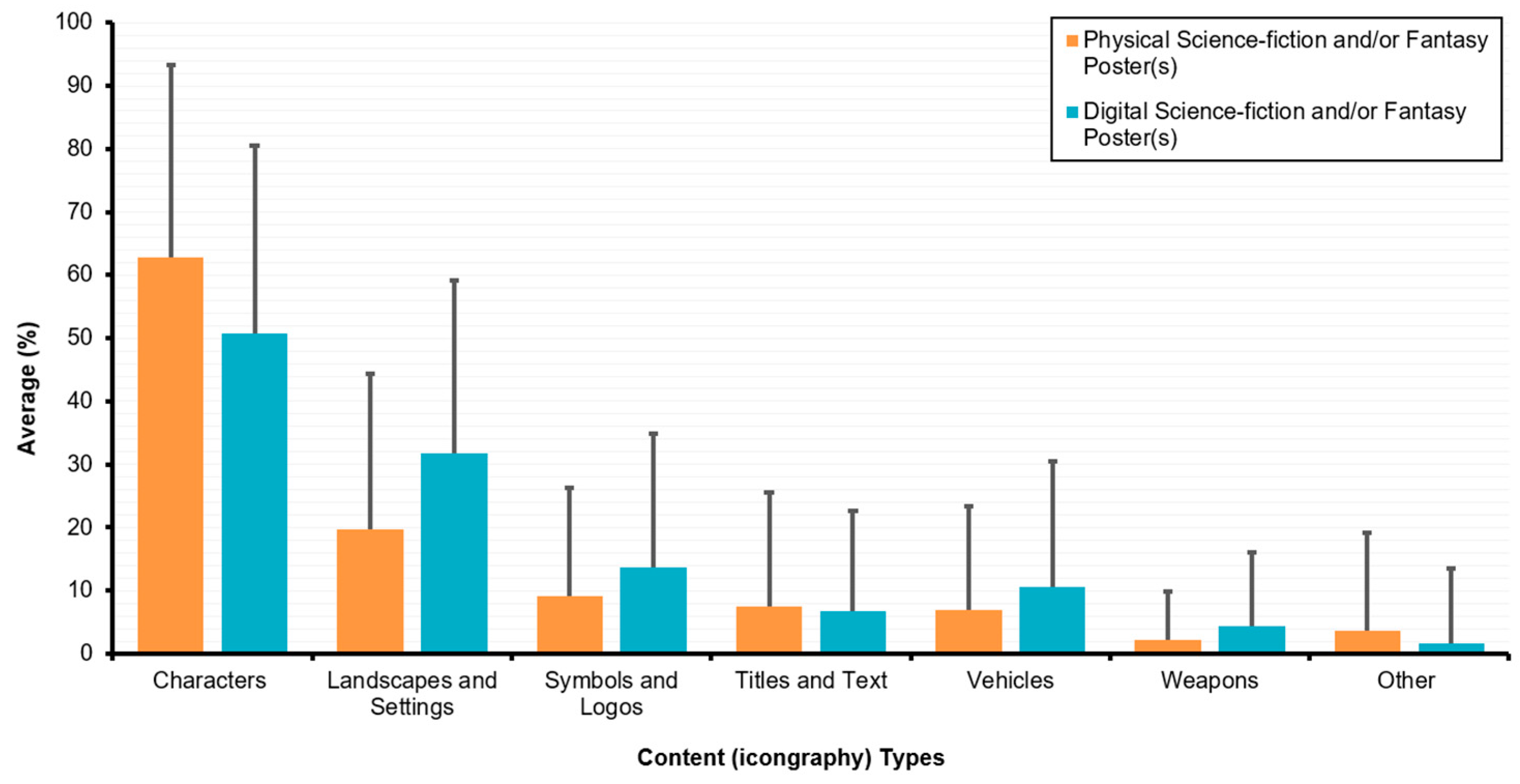

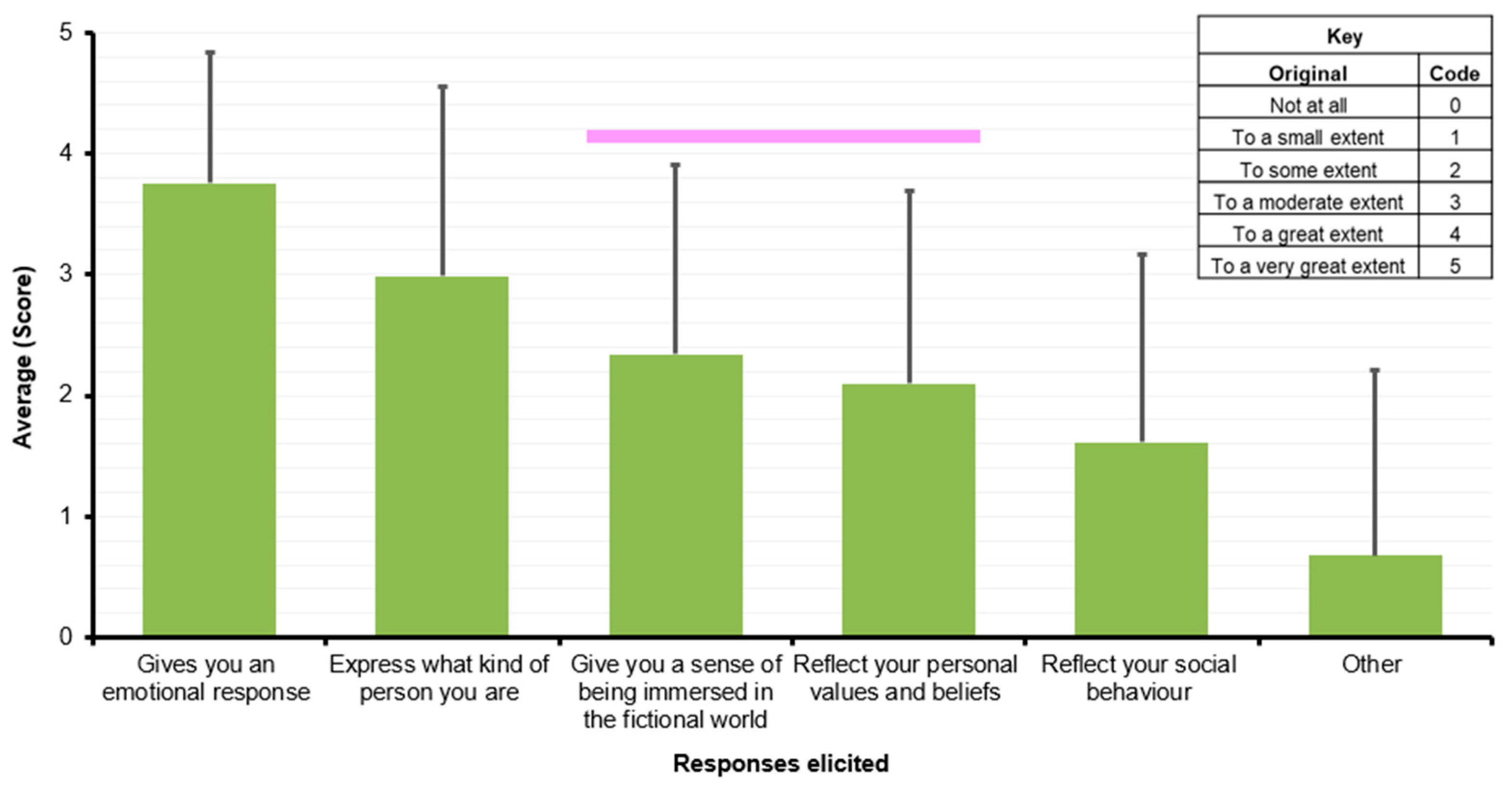

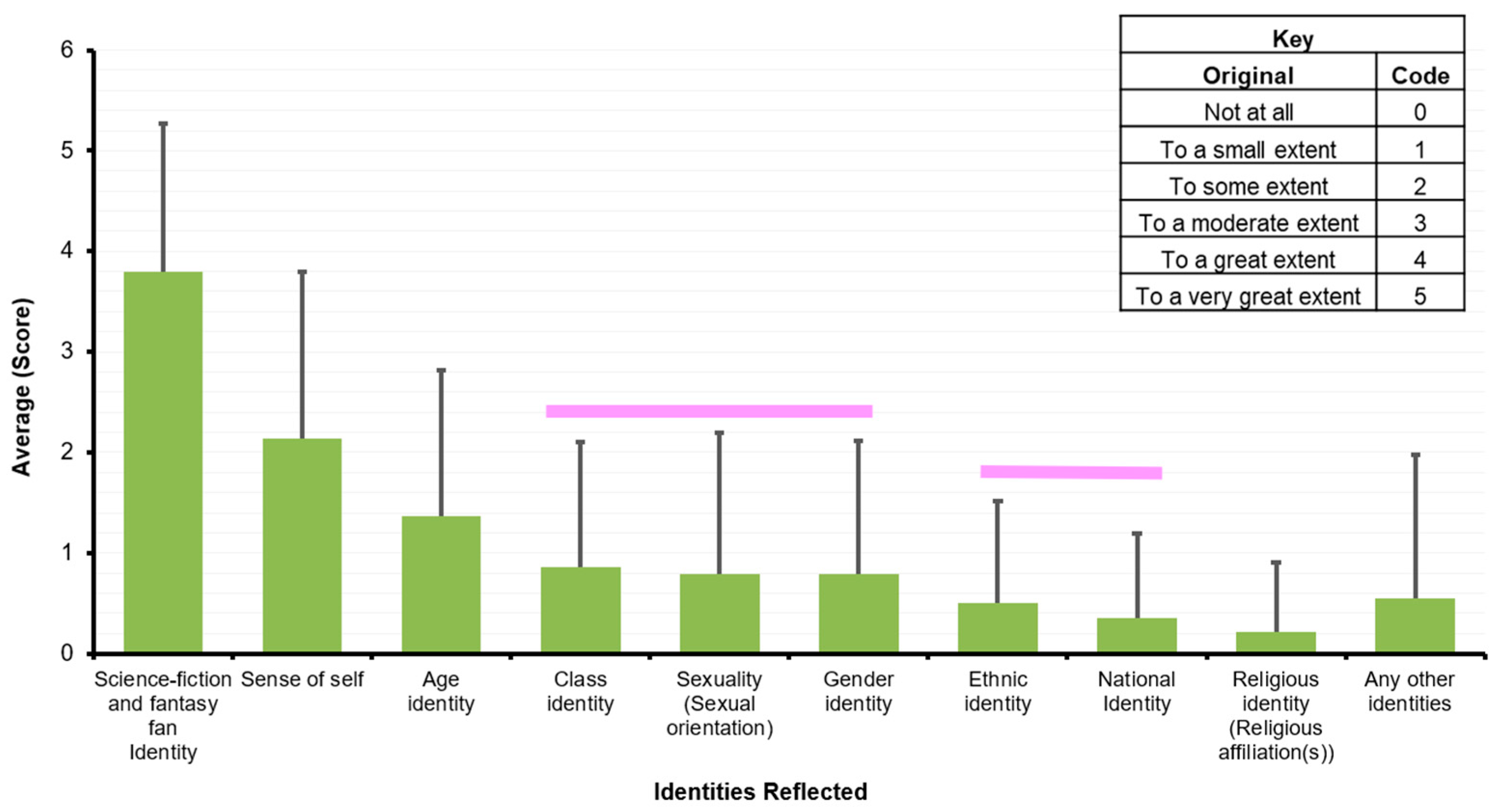

Furthermore, the survey treated elements like design and emotion or personal and cultural meaning separately, this was a practical choice to aid comprehension. The interviews revealed how these dimensions are in fact deeply interconnected, reflecting their complex theoretical entanglements. The results of the online survey provided pointers that were followed up in greater depth in the interviews. The prominence of characters within posters was of note (

Figure 3) and the survey results did indeed suggest that posters elicited responses such as emotion (e.g., a feeling of happiness) and a sense of the kind of person the respondent thought themselves to be. They also reflected a sense of identity, especially in terms of their being a fan of SFF but also having a sense of self. What was more surprising was the relatively low score given to posters for providing a sense of immersion in the different worlds conveyed by SFF. While SFF media themselves can be highly immersive, the posters appear to function more as symbolic reminders of those texts rather than as direct conduits for immersive experience. As reflected in

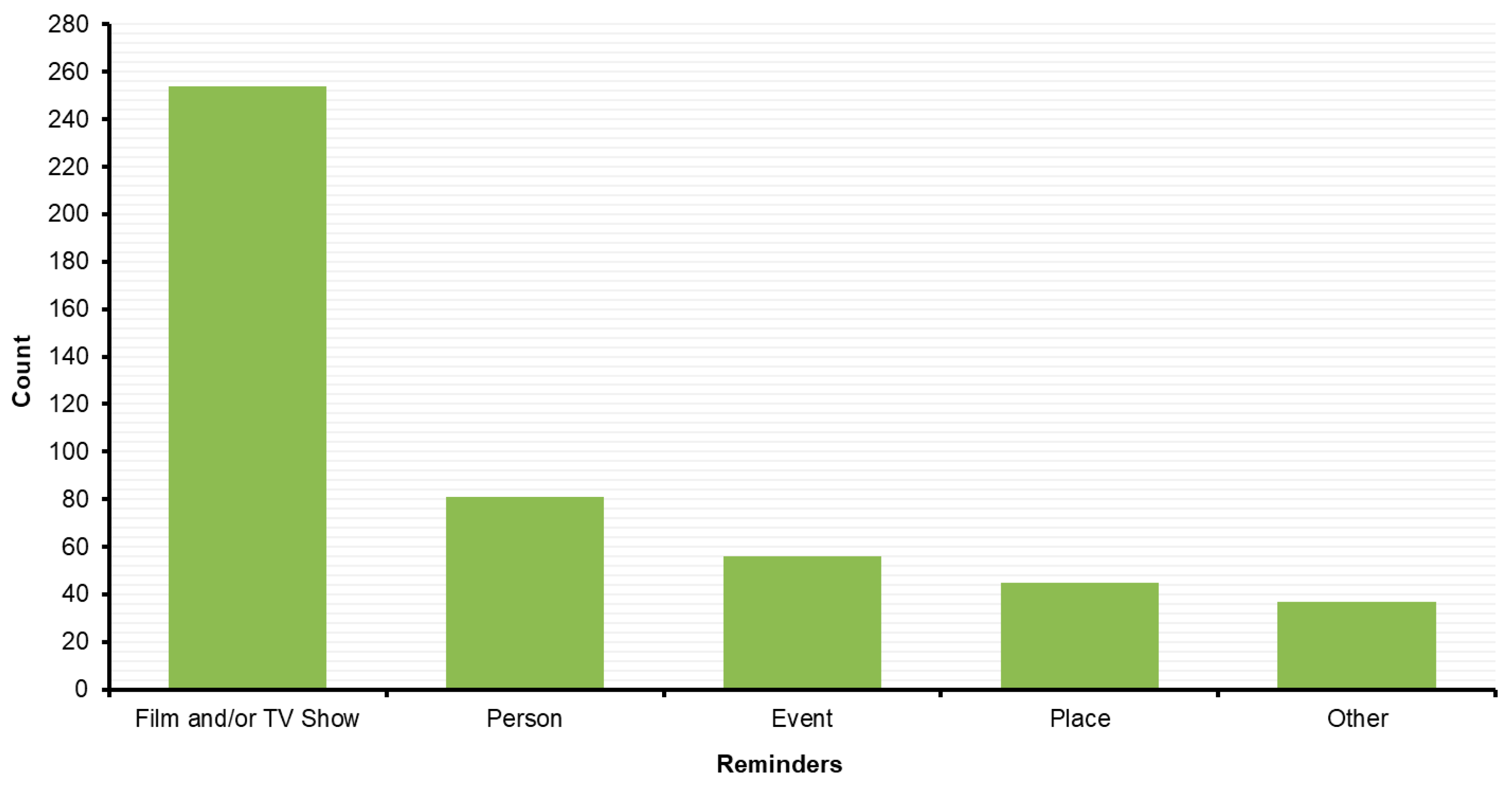

Figure 7, posters often serve as prompts for recalling movies and TV shows, rather than enabling immersion in their own right (

Figure 6). This suggests that the cultural significance of SFF posters lies less in transporting viewers into fictional realms and more in how they operate as personal and esthetic markers of identity, memory, and fan affiliation. As these points were followed up in greater depth during the interviews, they will be referred to generically as ‘results’ in this section, and they will be related back to literature and relevant theories.

It first needs to be noted that results suggest SFF posters have three types of significance for their owners, namely ‘esthetics,’ ‘functionality,’ and ‘personal significance’ (which includes both personal meaning and connection to the media text). These aspects primarily influence how poster owners perceive their posters in terms of their significance, but also potentially how others may observe them when displayed. This is related to points made by

Hebdige (

1979, p. 3), who argued that objects within a subculture can hold dual meanings—both utilitarian (aligned with ‘functionality’ and ‘esthetics’) and symbolic (‘personal significance’). However, one of these significances can be more valuable or be the only valuable significance to their owner. After all, some poster owners, such as Respondent 26, said they did not seek an emotional response from their posters. Instead, they valued them for purely esthetic reasons, like matching the room’s color scheme.

While some owners derive deeper emotional or immersive value from collecting, displaying, and observing these posters, others appreciated them primarily for their visual appeal or the brief imaginative thoughts they inspire, without experiencing significant emotional resonance. Given the inherently imaginative nature of the SFF genres, it is perhaps unsurprising that some owners described their posters as fostering a sense of connection to the fictional worlds represented—through visual cues or thematic references—rather than evoking a direct emotional response. These three significances will be discussed in terms of preferences owners have in terms of their posters and placement, emotional response posters give their owners, and how posters reflect personal identity.

4.1. Choices, Choices

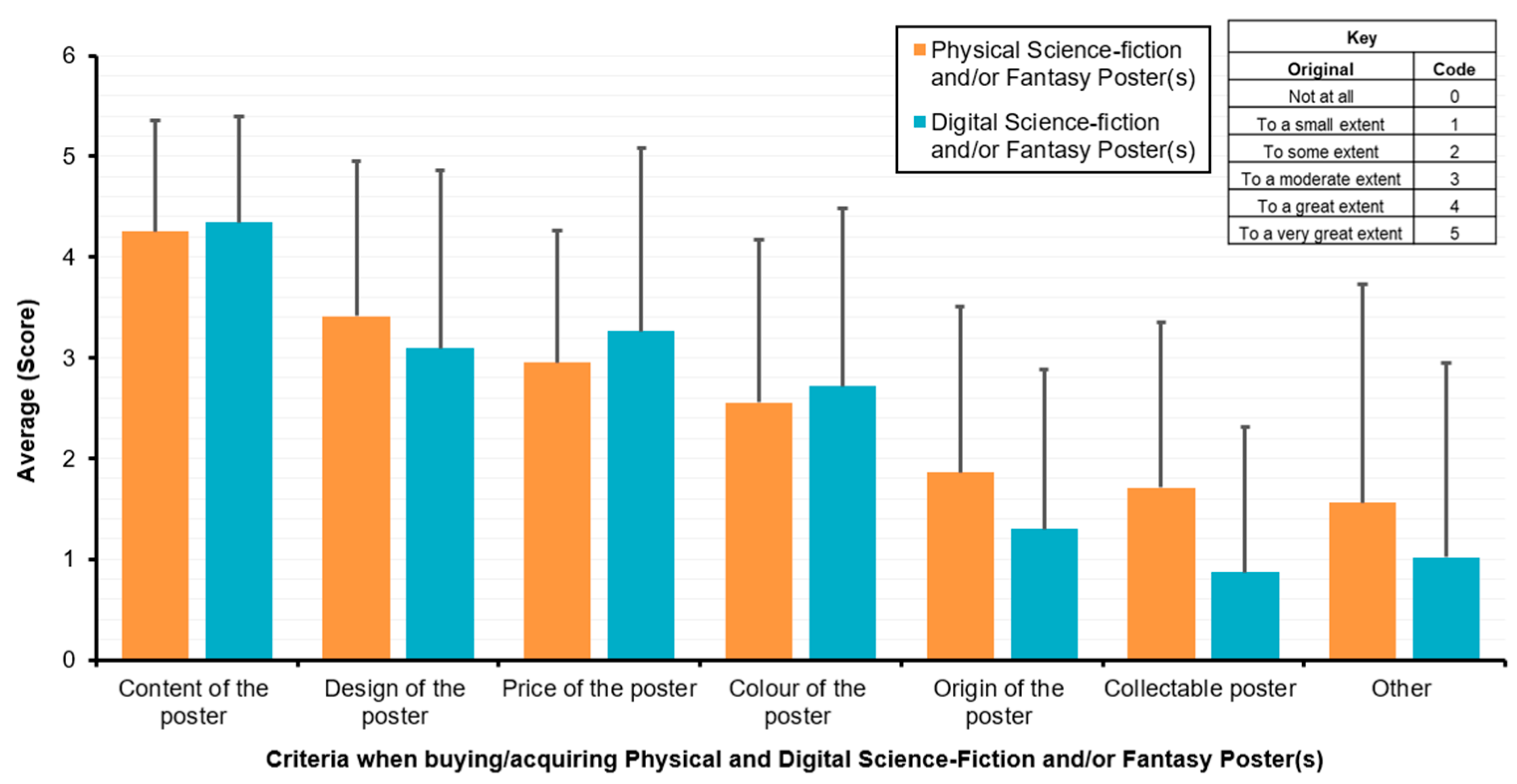

The results suggest that the type of poster, including its availability and components (such as content, design, and color), played a significant role in acquisition, with common elements consistently influencing owner preferences, as illustrated in

Figure 2 providing an illustration). Indeed, when it came to the factors that influenced poster selection, two of ‘The Big Three’—content and design—were paramount. Price also played a role, but for respondents, it was clear that content and design mattered. One reason respondents often referred to regarding their choice of poster to display was their esthetic appeal, which can make owners happy simply because they are pleasing to look at. As Respondent 12 noted, posters are “like any form of quality artwork … pleasing to the eye and mind.” However, enjoyment can vary depending on the “subject matter,” and someone uninterested in a particular genre may not appreciate a poster “no matter how beautiful the painting or artwork is” (Respondent 12). Clearly posters can function as art, and “being able to surround yourself with art that you enjoy has some kind of positive effect on you” (Respondent 20). This adds value for individuals who “collect art … to display it, and to look at it themselves, and to enjoy its existence” (Respondent 20).

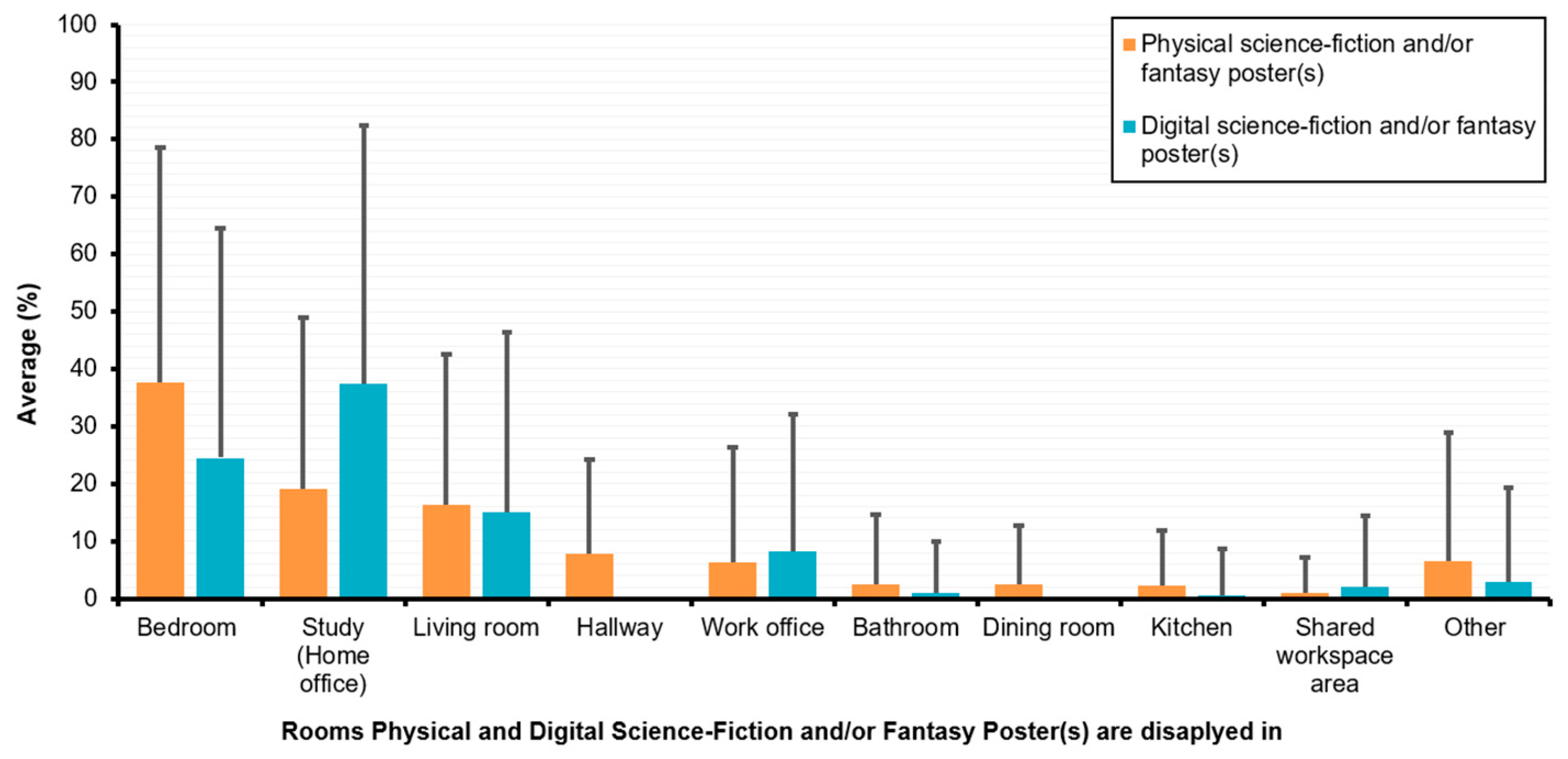

Physical posters tended to be displayed in bedrooms (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5), which is not surprising given that bedrooms are often the most personalized and frequently used spaces in the home (

Dey and De Guzman 2006, p. 901). In contrast, more open or shared areas—such as living rooms, hallways, workspaces, and home offices—were secondary choices for poster placement. These shared spaces, particularly the living room, often serve a different function. As

Rechavi (

2009, p. 133) notes, the living room is typically used to express and communicate one’s self and social identity to others through the objects displayed within it. In the interviews it was clear that the location and placement of the posters contributed to their meaning, often having a symbiotic relationship with the space they occupied, thereby enhancing the significance of both the poster and the room. This can positively affect the owner, offering mental comfort and often receiving positive feedback from others. Ultimately, the owner’s preferences, such as content choice and placement, are crucial to the significance of the SFF poster.

4.2. Emotional Response

The results suggested that posters evoked emotional responses (

Figure 6). For many of the SFF poster owners, although not all, eliciting an emotional response was an important factor in their connection to their posters. For some, this emotional engagement is a crucial aspect of their attachment, while for others, only specific posters evoked a meaningful reaction, often tied to personal experiences, nostalgia, or affinity with the media text they represent. As one participant reflected, fandom was “partly within my own personality”’ adding that removing a poster can signify a psychological shift: “it’s time to cut ties with something at that point” (Respondent 14). This supports

Kadyrgali et al.’s (

2024) assertion that “emotion is the most vital factor that connects the movie to the human”, which, in this context, extends to posters as emotionally resonant artifacts. Some owners expressed a need for their posters to continually elicit emotional reactions, not only at the time of acquisition but also upon repeated viewings—“the first time” to “the seventh time” (Respondent 24). However, emotional resonance may diminish over time as owners become desensitized or adapt to the constant presence of posters in their environment. Despite this, the presence of posters remains significant. For example, Respondent 21 noted that posters influence their overall “well-being and happiness,” while another participant stated that their absence led to negative emotional states, including feeling “trapped” and “isolated” (Respondent 9). Posters became a visual anchor during uncertain times, serving as a source of calm, a reminder of positive experiences, and creating a positive atmosphere, especially during difficult periods such as the COVID-19 pandemic, reminding them of better times. With those who lacked close relationships especially during social distancing, posters featuring characters, as indeed many of them did (

Figure 3), became like “friends” (Respondent 3) offering companionship, a sense of reassurance and comfort This aligns with

Wang’s (

2019) argument regarding the importance of text on a movie poster in fostering emotional engagement; however, it contrasts with his assertion that text primarily serves as a marketing tool to sell the media text. This highlights the emotional and psychological impact posters can have on their owners and connects with

McVeigh’s (

2000, p. 266) concept of consumutopia, which he describes as a consumerist “counter-presence to mundane reality fueled by late capitalism, the pop culture industry, and consumerist desire”. ‘Consumutopia’ involves the consumption of objects that offer immersive, idealized fantasies, even if unattainable. McVeigh identifies five traits of consumutopic objects—ubiquity, accessibility, projectability, a unifying leitmotif, and contagious desire. In this context, posters display two of these: projectability, the ability of an object to absorb and reflect personal meaning; and contagious desire, the impulse to display meaningful objects to reinforce emotional connection and identity. This emotional investment reflects how owners encode significance into posters, which in turn shape their psychological state. Similarly,

Appadurai (

1986) argues that objects accrue meaning through social circulation; posters become meaningful not solely for their design, but for the fantasies and affective attachments they embody. Conversely, the absence of posters being displayed can result in negative feelings and supports

Carney’s (

1994) argument that art (or decorative objects) serves both emotional and cognitive roles for individuals and groups. However, some owners may avoid posters that “invoke a negative emotional response” as Respondent 6 explained, “I don’t think it’s very healthy or very good to be actively seeking out things that just are negatively impacting us”. One negative emotion that posters can elicit is “heartfelt sad emotion”, such as grief where the poster serves as a reminder that those who have passed but are “still with me” (Respondent 28). This may at first seem strange given that the characters in the SFF posters are, of course, fictional but fictional narratives can provide a safe space where audiences can experience a range of emotions without needing to act on them in real life (

Smith 2022). Furthermore,

Smith (

2022) argues that emotional responses to fictional texts and real-life events are equally significant and legitimate, as fiction often draws from or refers to real-life elements or events.

Beyond the general emotional significance of posters, several respondents emphasized that the specific content—what the poster visually depicts—plays a critical role in shaping their emotional experience. For example, Respondent 28 noted that posters portraying a “good happy setting” contributed positively to their overall well-being. Owners often acquired posters that feature characters (

Figure 3) and these gave more of an emotional engagement as they felt “a little bit more real with a lot of different emotions” (Respondent 28) and owners felt that they resonate with aspects of their personality (

Figure 3). Posters featuring identifiable characters often strengthen the connection to the media text, and serve as reminders of the characters’ multifaceted nature, emphasizing their humanity and complexity. For Respondent 15, “characters that I have on my walls are touchstones for stories”, while landscapes are seen as “invitations to step into something new”. As shown in the summary provided in

Figure 3, landscapes and settings were the second most frequently featured aspects of posters. Respondents noted an open-ended quality to these visuals that allowed them to imagine the rest of the narrative. This quality was perceived to add “more value” to the poster and made it something that was, in the words of Respondent 7, “what I enjoy looking at.” This further reinforces

Chunyuan and Li’s (

2021) argument that film posters transmit information through their visuals, shaping audiences’ emotional experiences. Nonetheless, the prevalence of characters in the posters aligns with the statement made in the documentary

24×36: A Movie About Movie Posters (

2016) that studio-produced posters predominantly feature characters because “it’s a little bit easier to sell a movie by defaulting to the star face”. This reinforces

Smith’s (

2022, p. 54) argument that the emotional response to fiction is inherently ‘empathic’ and ‘sympathetic,’ as audiences form connections by engaging with the protagonist(s). Similarly, this emotional engagement can extend to poster owners and their connection to the characters depicted. This is supported by

Välisalo’s (

2017) study of audiences’ emotional responses to The Hobbit characters, which found that emotional reactions were strongly tied to the audience’s connection to the characters and the events depicted in the films.

For some, the emotional engagement with their posters was a crucial aspect of their attachment, while for others, only specific posters evoked a meaningful reaction, often tied to personal experiences, nostalgia, or affinity with the media text (the movie or TV show) they represent. These memories can relate to both the media texts themselves and the places where they were filmed. For example, Respondent 10 recounted a family holiday in New Zealand, where The Lord of the Rings was filmed. The Lord of the Rings poster reminded them of that trip, describing it as “one of the last times that we were together as a family” and reflected on it as a “good experience, a pleasant time”. This aligns with

Money’s (

2007) assertion that objects can possess embedded commemorative qualities. Additionally, it supports

Frost et al. (

2006, p. 24), who argue that movie posters serve as indicators of what owners “choose to remember,” whether that be their personal history or the historical significance of the poster itself. In this context, posters serve as prompts to elicit memories and experiences. As indicated by the survey results in

Figure 7, posters can connect owners to the stories of the media texts they represent and evoke the emotions associated with the experience of first watching them. Respondent 11 explained that posters “take me to certain aspects of the story” and “give me feelings of specific areas of the story”. For instance, their fan art poster of the science fiction movie

Serenity (2005) elicits a positive emotional response, giving them “warm feelings” as it reminds them of the story’s conclusion, where the characters survive the final battle and go on to live their lives. It is not the poster that does this per se but the poster as a vehicle for representing the movie. This strengthens

Gray’s (

2010) argument that posters act as paratexts of the media text, possessing synergistic elements that complement and enhance the media text without fully encapsulating it.

Gray (

2010, p. 52) describes posters as being “densely packed with meaning”, offering different dimensions of engagement. This also supports

Tuan’s (

1998, p. 194) and

Gabbiadini et al.’s (

2021) findings that engaging with SFF media texts can enable a sense of immersion even if this is not direct, and helps provide nuance to the, at first, surprising results shown for the importance of immersion in

Figure 6. Furthermore, it expands

Smith’s (

2022) argument that a media text’s narrative elicits specific feelings and experiences in the audience, demonstrating that this can also apply to posters. Although respondents themselves did not conceptualize their posters as paratexts in

Gray’s (

2010) terms, their accounts imply that posters operate paratextually—providing visual cues that evoke specific scenes or characters from the broader narrative worlds of science fiction and fantasy media.

When it came to poster type influencing their well-being, a point hinted at by the online survey results but explored in greater depth in the interviews, physical posters held particular significance for some owners due to their tangible nature. Respondent 22 described physical posters as “tactile” and noted that being able to “look at it just feels more kind of real, like it’s more of a real presence in the world and a reminder of my connection to that”. Similarly, Respondent 12 highlighted the importance of a poster’s “bigger size and the tangibility of the object”. However, for others, the content of the poster was a more significant factor than its type. As Respondent 19 explained, “It’s the medium—it’s not important to me. It’s the content”. This suggests that while physical posters offer unique benefits relative to digital posters, the overall impact of a poster often lies in its subject matter. In addition, other objects, aside from posters, can also evoke emotional responses and serve as reminders of media texts. The presence, or absence, of such objects can affect mood, sense of self, and overall psychological well-being, demonstrating that posters function as more than just visual decoration; they are emotionally charged cultural artifacts embedded in everyday life.

4.3. Posters and Personal Identity

In many ways, the results suggested that SFF posters functioned as a form of self-expression, akin to other personally meaningful objects (

Figure 6). They not only reflected individual interests and esthetic preferences but also served as markers of the owner’s SFF fan identity and sense of self (

Figure 8). Posters carried significant “informational value”, as “each one [poster] communicates something” about its owner, even if it is simply a “reference” to what they “care about or enjoyed” (Respondent 20). Surrounding oneself with items like posters “help[ed] you cultivate who you are as a person in a way that you’re happy with” (Respondent 6). They also serve to “reflect” and “reaffirm” (Respondent 20) aspects of the owner’s identity when viewed. Indeed, the decision-making process when acquiring a poster often involves careful consideration regarding what it communicates about the owner even being “in some way is probably a very large element” (Respondent 20). Indeed, as Respondent 23 observed, “anything you purchase has a small reflection on you”, whether intentional or not. Decorating a space that they occupy allowed owners to “externalize” and maintain their self-identity, “even if I’m not consciously thinking about it when I get any given poster” (Respondent 20). For Respondent 15, posters go even deeper, serving as “an external representation of my internal mental landscape”, reflecting aspects of themselves that they “don’t have words for”. However, while the online survey did point to a broad link between posters and self-identity (

Figure 8), the interviews suggested that a poster owner’s sense of self and how they identify who they are is highly subjective and varied greatly between individuals. Some of this is hinted at with the analysis of sense of self and the SAR groups in

Table 4. Indeed, it strengthens the assertions of

Isfandiyary (

2017),

Case (

2009), and the

Victoria and Albert Museum (

2021) that “posters have been a vital means of communication” and one way that posters facilitate communication is through ‘silent conversations’ between owners and their possessions (

Abram 1996). In this context, posters communicate key aspects of the owner’s identity, such as their values, interests, and sources of enjoyment, offering a non-verbal medium for self-expression and reflection. Posters provide an accessible way to “make these kinds of statements about oneself”, enabling others to “read what the posters say about me” (Respondent 20). Ideally, these statements convey something “moderately positive” (Respondent 25), offering others an opportunity to decide whether to pursue a relationship (Respondent 10). This reinforces

Chadborn et al. (

2017) argument that fan objects serve as tools for fostering positive social engagement, allowing individuals to express aspects of their identity and enabling others to interpret and respond to these self-representations. However, owners were aware that posters may also communicate something negative or unsettling to others. This supports

Hall’s (

1973) reception theory, particularly the concepts of ‘negotiated readings’ and ‘oppositional or resistant readings’ where the owner interprets the meaning of the poster in relation to aspects of their identity, while others might not fully agree or might reject the meaning altogether.

For some interviewees, posters may reaffirm specific aspects of their identity, such as being a SFF fan, rather than their entire sense of self. For Respondent 10, their interest in SFF is a core part of their identity: “It has shaped the sort of person I am… my values… and being open to exploring other ideas”. This supports

Grossberg (

1992) argument that being part of a fandom actively contributes to the construction of an individual’s identity. For instance, Respondent 23 stated that posters “definitely” reaffirm their identity as a sci-fi and fantasy fan because “they’re just such direct references”, thereby showcasing their passion for the genre; a point that reinforces

Borer’s (

2009, p. 1) and

Frost et al.’s (

2006, p. 24) argument that fans use objects to display and reflect their fandom. Respondent 28 described their posters as a way of “keeping it around, keeping me involved in the worlds and spaces created by the film or book”. This strengthens

Poole and Poole (

2013) assertion that movie poster collectors can “own a piece of the movie” in tangible form, serving as a lasting memento of the media text. Displaying a poster signifies that it has “passed the test” of suiting their tastes and reflects their sci-fi and fantasy identity (Respondent 22). These findings reinforce recent research suggesting that fan identity affirmation leads to increased engagement, demonstrating the affirmative significance that the fantasy genre and fandom can have in fans’ lives (

Groene and Hettinger 2016).

Posters communicate various aspects of their owners—such as personal interests, fandom affiliations, and emotional attachments—and often serve as symbolic expressions of identity (Respondent 11). However, participants also acknowledged the limitations of using posters to fully convey their beliefs or personality traits, suggesting that meaning is not fixed or universally understood. This dynamic reflects

Hall’s (

1973) encoding/decoding model, which theorizes that media texts are encoded with intended meanings by producers, but those meanings are subject to negotiation or resistance by audiences based on their social and cultural frameworks. In this context, poster owners may ‘encode’ their self-expression into the posters they choose to display, yet they remain aware that others may interpret these displays differently. For example, a poster that represents nostalgia for one viewer might be read as trivial or decorative by another. Such interpretations align with Hall’s notion of negotiated readings, where meaning is partially accepted but reinterpreted, or oppositional readings, where the viewer rejects the intended message entirely. Thus, the act of displaying a poster becomes an inherently communicative and interpretive process, shaped by both personal intent and audience perception.

For some of the interviewees, posters served as a means of expressing their convictions and reflected their beliefs, opinions, philosophies, values, and what was important to them. Posters can communicate what matters most to their owner and conversely, they may avoid displaying anything that contrasts with their beliefs. Respondent 24 noted that their posters conveyed their “philosophy as a human” and what they “value”. These choices also serve to non-verbally signal to others that they are “welcome here” (Respondent 15) and to foster connections with like-minded individuals (Respondent 19). This supports

Habermas’s (

1991) argument that spaces within the home grant owners the agency and control to personalize and decorate their environment. By encoding their posters with significance, owners can create a positive ambience and atmosphere.

On the other hand, some owners derive value from nostalgia, and their posters were “just a picture on a wall” (Respondent 25) rather than reflecting their identity. This suggests that while posters can reinforce identity for some, others may find their primary significance in the emotional connections they evoke.

4.4. Into the Future

Perhaps understandably, most existing research on media posters has focused on their commercial role as advertisements, but this study approached them from a different perspective. Additionally, while there is extensive literature on media posters, little has specifically examined the SFF genres. A key message emerging from this research is that SFF posters hold significant meaning for their owners, and the findings contribute to fandom studies and material culture research by demonstrating that SFF posters are more than just advertisements for media texts—they can indeed carry deep personal and cultural significance. However, while the research has pointed to many aspects of the relationships between SFF posters and their owners, there is much more that needs to be explored.

Firstly, it does need to be noted that the COVID-19 pandemic-imposed restrictions on in-person data collection prevented interviews in the spaces where SFF posters were displayed. It also made other potential methods, such as focus groups and event-based observations (such as at conventions or makeshift SFF poster stalls), unfeasible. Future research should conduct in-person interviews in participants’ homes, observe individuals acquiring SFF posters in real-time, and engage with SFF poster artists, retailers, and convention sellers to gain additional insights.

Secondly, while many countries have their own movie industries, and the SFF genres have had multiple cross-influences, this research was focused on respondents domiciled in Europe and North America; respondents from these places accounted for over 70% of the total number of respondents. It is possible, indeed likely, that applying the same research methodology set out here with fans living outside these locations could generate different results. This would be an intriguing study. However, even if the research is extended to other socio-cultural contexts, it would be necessary to employ a stratified sampling approach to ensure representation across key demographic variables, such as nationality, age, gender, and socioeconomic background.

Thirdly, a longitudinal study tracking the social and cultural lifecycle of an SFF poster, from acquisition to ownership, display, and possible storage or disposal, would provide deeper insights into the evolving significance of posters over time. This could help tease out the long-term dynamics of poster ownership and display. Indeed, one approach may be to focus on such a lifecycle-based analysis for a specific media text, such as the Star Wars franchise, given its long-running (since the 1970s) legacy and presence across multiple media formats, including books and games.

Fourthly, another future study that focuses on the communal aspect of collecting posters rather than the individual poster ownership in this study could be considered. This was found in this study as some interviewees did discuss others seeing/showing and having conversations about their posters. There are online communities, conventions, and collector forums where poster value is debated and displayed.

Fifthly, another study could explore in greater depth the fan hierarchies of taste in terms of posters. This was briefly touched upon in this study in terms of poster ownership, but more depth could generate interesting results. Notions of value extended beyond financial worth to possibly include emotional resonance, rarity, official status, association with specific eras or films, older posters and teaser posters. For example, older posters could be described as “authentic” or “special” due to their age, original print status, or connection to formative viewing experiences.

Sixthly, a study could explore how the nostalgic affective dimension is central to poster significance. In this study, some interviewees stated that their posters evoked nostalgia, were often framed as mnemonic devices, reminding participants not only of the films themselves but of the life stages when those films were first encountered. Another form of nostalgia for owners could be the components of the poster itself. For example, posters with dated design styles (e.g., hand-drawn illustrations or vintage typography) evoked a strong sense of period, contributing to their perceived authenticity and emotional appeal. Perhaps collecting older posters could be a way of “preserving” owners’ media history, reinforcing the idea that fan collections are archives of self and memory.

Finally, a study could explore the evolution of poster esthetics and how this esthetic shift may influence collecting practices. The comparison between earlier iconic posters (e.g., Jaws) that have minimalism, symbolic power, and uniqueness and recent posters that have an ensemble-cast design with high-saturation color palettes and dramatic symmetry (e.g., Endgame) further illustrates how poster design reflects broader industrial and esthetic trends. Exploring this evolution of poster esthetics in relation to collecting practices would be intriguing.