Abstract

This research was designed to explore science-fiction and fantasy (SFF) posters, specifically those related to films and television shows, from the perspective of their owners, examining their potential as sources of social and cultural significance and meaning. The research explored these in terms of the content of the poster, placement, media texts they reference, morals, behavior, identity, sense of self, well-being and self-expression. Data collection took place between 2020 and 2022 via an online survey (N = 273) and follow-up semi-structured interviews (N = 28) with adult science-fiction and fantasy film and television show poster owners. The significance and meaning of SFF posters were framed by two conceptual models: ‘The Three Significances’—esthetics, functionality, and significance (both spatial and personal)—and ‘The Big Three’—content, design, and color. Among these, content held the greatest significance for owners. Posters served as tools for self-expression, reflecting their owners’ identities, affinities, and convictions, while also reinforcing their connection to the media they reference. Posters helped to reinforce a sense of self and fan identity and evoke emotional responses, and the space in which they were displayed helped shape their meaning and significance. The paper sets out some suggestions for future research in this important topic.

1. Introduction

Posters are more than mere advertisements aimed at promoting a product; they are cultural artifacts and commodities and are often claimed to hold a visible and meaningful place in the social and personal lives of individuals and communities. As paratexts, media posters serve as extensions of and connections to broader media products, such as films, television shows, and games, while also operating as independent cultural artifacts (Gray 2010; Freeman 2017). Hence, media posters “play a key role in outlining a show’s genre, its star intertexts, and the type of world a would-be audience member is entering,” functioning much like other cultural objects (Gray 2010, p. 52). They contribute to the completion, enrichment, or enhancement of the media experience through the incorporation of synergistic visual and textual elements (Gray 2010, pp. 6–7). Wang (2019, p. 423) further asserts that “the movie poster determines the success of the film to a certain extent,” underscoring its relevance in shaping audience engagement. Posters offer distinct dimensions of media interaction, exemplified by the existence of two main types: physical and digital. Physical posters have historically been used in public spaces as advertisements, appearing in cinemas, on billboards, and across public transport (Frost et al. 2006, p. 21), and are often sold as merchandise to be displayed in private settings. The price of physical posters, however, varies significantly depending on the seller, material, collectability, and other value-enhancing features. By way of contrast, digital posters have risen to prominence in the internet age and are typically promoted by media companies through social media platforms and used by consumers as wallpapers on computers and smartphones. Both physical and digital posters are generally affordable, with digital posters frequently accessible for free or via specialized poster platforms such as PosterSpy.

Posters, whether digital or physical in form, may be categorized as either official, produced by studios primarily for marketing purposes, or unofficial, often fan-created artworks referred to as ‘fan art’. Media posters thus function simultaneously as advertisements and commodities, transforming intangible media texts into tangible cultural products (Gray 2010, p. 6). As Meng and Shen (2021) argue, posters possess value that extends beyond their commercial and utilitarian purposes, encompassing cultural, artistic, and symbolic significance. This density of meaning stems from the necessity for a poster to convey the core themes, mood, and identity of a media text through a single, static, two-dimensional image. The Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) describes posters as “a vital means of communication” (Victoria and Albert Museum 2021), and Isfandiyary (2017), Case (2009), Wang (2019), Chunyuan and Li (2021), and Chen and Gao (2013) all support the view that posters communicate a wide range of messages, spanning commercial and political to cultural and personal. The Victoria and Albert Museum (2021) notes that posters have promoted everything from products and performances to political causes and social movements, making them “compelling visual evidence of our social and cultural history”. Case (2009) adds that posters can also act as deeply personal objects, expressing individual identity, taste, and interest.

In the realm of visual media such as film and TV, posters often serve as the first point of engagement between a viewer and a media text, offering a condensed visual narrative (24×36: A Movie About Movie Posters 2016; Wang 2019; Meng and Shen 2021; Chunyuan and Li 2021). Wang (2019, p. 423) notes that “the main purpose of poster design is to convey the theme and content of the film, as well as to promote important information.” This is exemplified in the iconic Jaws (1975) poster by Roger Kastel, which features a massive shark emerging from the ocean, mouth agape, beneath an unsuspecting swimmer. The bold, red colored used for the title and limited yet impactful iconography convey the film’s themes of suspense, terror, and isolation with striking clarity (Rhodes and Singer 2024; IMDb 2024). In the 1950s, due to limited special effects budgets, film posters became an essential tool for capturing the public’s imagination, often surpassing the films themselves in quality.

In the absence of sophisticated on-screen visuals, audiences were required to rely heavily on their imagination to bridge the gap between the promise of the poster and the reality of the film. Rhodes and Singer (2024) claim that such posters can be “remembered even without having seen the movie,” because they “signify and induce expectations and desire,” creating intrigue independently of the film itself. Hence, media posters represent a unique form of engagement with an audience and are thus an extension of the media text and a standalone cultural artifact. With the rise in digital technologies and the refinement of visual effects, contemporary media texts now frequently match, or even surpass, the visual quality promised by their promotional materials. This shift underscores the evolving role of posters in media culture, as unlike other forms of merchandise, such as action figures, posters offer the first visual impression of a media text. They provide a distilled and stylized representation of richly imagined worlds, acting as both a marketing tool and a narrative gateway.

While their primary function has historically been commercial, designed to help sell the media text, many individuals own and display media posters within their personal spaces. As noted by Dawsons Auctions (2024), “posters for movies are also among the most actively collected, representing a simple way to show off your love of both cinema and art”, especially when compared to other forms of fan merchandise As Appadurai (1986, p. 5) notes, cultural objects become meaningful through the human actors, be they companies, fans, or collectors, who encode significance into their forms, uses, and trajectories. Gray (2010, p. 52) similarly emphasizes that posters are “densely packed with meaning” by their creators, making them ideal for investigating how intended meanings intersect with personal interpretations and uses. However, despite this apparent richness and importance of media posters, there is a relative absence of published studies which explore the potential significances and meanings they hold for their owners. This is perhaps surprising given the importance of film and TV media in society as asserted by Marshall McLuhan—“the key factors that determine the social form of human history are not politics, economy and culture but media” (Chunyuan and Li 2021, p. 1).

There is clearly much scope for research here into the inter-relationships between media posters and their owners, but, of course, there are many genres of entertainment in the movie and TV spheres and addressing all of them would be an enormous challenge. Hence, the focus of the research set out in this paper was specifically on posters linked to science fiction and fantasy movies and TV shows. These two genres are related but also different and were selected over other media genres primarily because they offer a vast imaginative landscape populated by diverse worlds, environments, and characters. These genres provide a unique capacity for transcending the limitations of time and space, inviting viewers to envision realities that are both different from and reflective of our own. As such, they serve not only as visual artifacts but also as portals into alternative realms, making them particularly compelling for exploring questions of meaning, identity, and emotional engagement. Renowned science fiction writer Ray Bradbury famously emphasized the significance of the genre as “the most important literature in the history of the world, because it’s the history of ideas, the history of our civilization birthing itself. ...Science fiction is central to everything we’ve ever done, and people who make fun of science fiction writers don’t know what they’re talking about.” (Olympia Publishers 2024).

Fantasy is the older of the two genres, with its roots tracing back to the pre-modern world of myth and religion. It has historically served as a symbolic means of articulating universal human challenges, such as birth and death, often through the representation of gods and mythical figures (Blum 2011). Mathews (2002, p. 2) defines fantasy as “a fiction that elicits wonder through elements of the supernatural or impossible. It consciously breaks free from mundane reality”. Similarly, Lynn (1983, p. ix) suggests that “fantasy deals with the impossible and the inexplicable” and primarily incorporates supernatural elements such as magic. Roberts (2000, p. 1), states that “science fiction as a genre or division of literature distinguishes its fictional worlds to one degree or another from the world in which we live: a fiction of the imagination rather than observed reality, a fantastic literature”. Bradbury goes much further and asserts that “A science fiction story is just an attempt to solve a problem that exists in the world, sometimes a moral problem, sometimes a physical or social or theological problem.” (Bradbury 2004, p. 108). Recent scholarship challenges this over-simplified divide between science fiction and fantasy. Rieder (2010) argues that genre definitions depend more on historical and institutional contexts than fixed traits, while Canavan and Link (2019) frame SF as a contested category. While both science fiction and fantasy (SFF) originated in literary forms such as books and magazines, they have since flourished in visual media, becoming a dominant force in contemporary entertainment (Broderick 2003, p. 59). Once regarded as a marginal or ‘B-movie’ genre in the United States during the 1950s (Schauer 2017), science fiction in particular began to gain mainstream popularity in the 1980s, marked by the success of blockbuster films such as Star Wars (1977) and Back to the Future (1985) (The Numbers 2024a, 2024b), and this has continued into the present day. For example, as of 2020, the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU), comprising 23 films, had collectively grossed USD 22,590,455,007 worldwide, making it the highest-grossing film franchise in history (The Numbers 2020). These examples underscore the growing cultural and economic significance of the SFF genres. This shift is largely attributable to technological advancements, such as the use of computer-generated imagery (CGI), which have enabled the visualization of fantastical worlds with a level of realism that was previously unattainable (Prince 2002; Chunyuan and Li 2021).

While previous studies have explored the marketing or esthetic functions of film posters through textual and visual analysis, few have examined how fans and owners themselves interpret, display, and attribute meaning to these artifacts. This study distinguishes itself by focusing on the lived experiences of poster owners’, using survey and interview data to analyze how posters function as tools of emotional connection, personal expression, and fan identity. As such, the work expands on studies like Chen and Gao (2013), which emphasize content analysis, by centering the voice of the audience as meaning-makers. The research reported here aimed to understand the inter-relationships that owners have with their posters. As noted above, this is a relatively underexplored area of social life, and this paper will serve to be a lens through which to examine the broader world of fandoms and posters as cultural artifacts and potential sources of significance and meaning to owners. This study adopts a cultural sociological approach to “meaning” and “significance,” drawing on theories of material culture and identity (Belk 1988; Appadurai 1986). In this context, meaning is understood as the subjective, emotional, and symbolic value ascribed to posters by their owners, while significance refers to their perceived relevance in shaping self-expression, esthetic preferences, and personal or social identities. The research sought to address questions such as whether these posters simply serve as decorative windows into fantastical realms or do they carry deeper cultural significance and meaning for their owners. If so, what are these meanings, and how do they manifest in the everyday lives of poster owners? Do the posters reflect the values, behavior, identity, sense of self, emotional well-being, and self-expression of their owners? There is much theory that can be drawn on here. For example, do SFF media posters serve as a “different mode of self-presentation” (McVeigh 2000, p. 225), reflecting their owners’ interests and identities? This aligns with Tilley’s (1999, p. 76) claim that “things create people as much as people make them,” Belk’s (1988, p. 139) view that possessions shape identity, and Jenkins’ (1992) argument that fan engagement with media objects plays a central role in expressing and constructing identity. Myths, and, by extension, media narratives, are said to offer frameworks for understanding and navigating life’s challenges (Campbell and Moyers 1991), and Kadyrgali et al. (2024) suggest that “emotion is the most vital factor” connecting audiences to media texts. This all resonates with Smith’s (2022) assertion that narratives elicit specific feelings and experiences, which could be extended to posters as visual extensions of those texts.

This research was based on data collected through an online survey and a follow-up set of semi-structured interviews that took place between 2020 and 2022, a period that spanned the COVID-19 pandemic and its immediate aftermath. Respondents were mostly from the Western world context, but it is important to note that this focus refers to where the respondents were primarily located and does not reflect the geographical origin of the media texts or the posters themselves. The following section sets out the materials and methods for data collection and analysis, and this is followed by a presentation of the online survey results. The paper then moves on to a discussion of these results and how they were subsequently explored in the interviews, and how they related to wider literature. The final section of the paper sets out some key conclusions that emerged.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Online Survey

The study initially employed an online survey-structured questionnaire to collect primarily quantitative data from a sample of 273 respondents, all of whom were SFF movie and/or TV series poster owners. The online survey was created using JISC (www.jisc.ac.uk, accessed on 10 April 2025) and was embedded on the website (www.windowsoffantasy.com, accessed on 10 April 2025). In the online survey, the respondents were asked to conduct their own multimodal discourse analysis, similar to the approach taken by Chen and Gao (2013), but specifically on their own posters. This was facilitated through questions encouraging them to reflect on the visual, textual, and symbolic elements that shape their posters’ meanings and personal significance. The survey (see Supplementary Material S1) commenced with an introduction expressing gratitude to participants for their involvement and included a link to a Participant Information Sheet and Consent Form. After this, respondents were directed to the survey questions. The first question asked whether participants owned physical posters, digital posters (poster images used primarily as wallpapers or background displays on personal devices, such as laptops, tablets, and phones), or both, and based on that answer, respondents were directed to the corresponding set of questions tailored to their poster type. While the questions for physical and digital posters were similar, they included specific queries relevant to each format. Most questions used multiple-choice options (e.g., tick boxes, scoring) to make the survey quick and easy to complete. Respondents were asked to provide counts, estimate percentages, or respond using a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 5 and covering ‘Not at all’ to ‘To a very great extent’ to explore the potential significance of posters to their owners, it is acknowledged that this method introduces a degree of researcher-led framing. By offering predefined categories such as emotional response, identity reflection, or spatial esthetics, the survey may have limited the opportunity for participants to articulate other dimensions of significance not captured by those options. However, the structured format was intentionally chosen to enable comparative analysis across a broad respondent base (N = 273) and to quantify the relative importance of specific factors. To mitigate the constraints of this approach, open-ended comment boxes were included throughout the survey, allowing participants to elaborate in their own words. Respondents were also asked to provide some limited demographic information, including national identity, age, religion, disability, social class, gender, and ethnicity. At the end of the survey, participants were invited to indicate their interest in participating in a more in-depth interview. Those who agreed were asked to provide their name and email address and were contacted via email to arrange a mutually convenient date, time, and location for the interview. The information collected from their survey answers was subsequently used to inform and structure the interviews.

2.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

The semi-structured interviews (28 in number) comprised a set of open-ended and closed questions (Marshall and Rossman 2014, p. 92) (see Supplementary Material S2). The interviews were conducted after the online survey results had been analyzed. Furthermore, the subsequent semi-structured interviews (N = 28) were designed by being opened-ended to explore these dimensions in greater depth, offering space for participants to reflect more freely and potentially introduce meanings outside the initial survey framework.

Additionally, the interview data captured more fluid, nuanced, and cross-cutting interpretations that informed the final thematic analysis. Most interviews lasted approximately two hours, although some extended to four hours. Depending on the participants’ preferences and/or practicality, interviews were conducted either in person (face-to-face) or via online video calls, especially as these occurred in the immediate post-COVID pandemic period. Hence, 27 out of the 28 interviews were conducted via Zoom or Teams. While the use of online video call platforms offered logistical advantages, such as overcoming geographical barriers, it also posed certain limitations (Burke and Patching 2021). For example, the inability to observe participants’ body language during the interview presented a challenge in fully capturing non-verbal cues, which were an important aspect of communication.

2.3. Recruitment and Demographic Profile of Respondents

The respondents of the online survey were aged between 18 and 74 and were required to own SFF movie and/or TV posters. The aim was to achieve a gender balance during data collection; however, this proved challenging due to the male-dominated nature of SFF fandom, as noted by Morrissey (2017, p. 354). Respondents were recruited through announcements at club and society meetings, emails, and posts or messages on social media platforms, including Facebook, Twitter (X), Instagram, Tumblr, and Reddit. Social media proved to be a valuable tool for recruitment, particularly during lockdowns, as it facilitated broader reach and engagement with potential respondents (Calvo et al. 2024). To identify potential participants, relevant communities and social media pages were searched for, focusing primarily on English-speaking regions such as Australia, the United States, Ireland, the United Kingdom, and Canada. The search terms included phrases such as ‘science-fiction posters’, ‘fantasy posters’ and names of well-known or recent SFF films and TV shows. Additionally, a snowball sampling technique was employed whereby survey respondents were asked to share contact details of any club or society meetings and social media groups or pages (e.g., on Facebook, Twitter (X), Instagram, Tumblr, and Reddit) they believed might be interested in participating in the study. Respondents were also encouraged to share the survey link within their networks to increase outreach (Naderifar et al. 2017). Social media platforms, profiles and pages were designed to share posts and communicate with other pages and groups and interact with potential participants. These platforms were Twitter (X), Instagram, Tumblr, Facebook, Reddit, and Discord. For all respondents, it was explained that the study had received ethical approval from Brunel University.

Respondents for the semi-structured interview phase were self-selected from those who took part in the online survey. The poster(s) owners who took part in the online survey (Table 1) were predominantly male, men aged 18 to 24, primarily from English-speaking countries or continents, white, heterosexual or straight, non-religious (e.g., atheist), and middle class, and this profile broadly mirrors trends found in SFF fandoms (Morrissey 2017, p. 354; Soto 2020, p. 3). Some 40% of the online survey participants came from North America and a further 30% from Europe (including the UK). As can be seen from the Chi-square and correlation tests in Table 1, the profile of respondents for the semi-structured interview phase broadly mirrored that of the online survey.

Table 1.

Summary of the demographic characteristics of the online survey respondents (N = 273) and interviewees (N = 28). Please note that in the online survey, some respondents selected more than one answer from those offered to them. As all answers were treated equally and included in the overall count, in some cases where respondents selected more than one option, the total number of responses exceeded 273.

2.4. Data Analysis

The data from the online survey were analyzed primarily using descriptive devices such as tables and graphs. Some statistical analysis was employed, with a primary focus on the Kruskal–Wallis Test and crosstab (Chi-square) analysis, conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 29. These statistical techniques helped identify significant differences across various categories such as criteria, responses, identities, and perspectives, including SAR (Sex, Age and Religion). SAR represented respondents’ characteristics grouped into categories: sex (male vs. female), age (younger respondents: 18 to 34 vs. older respondents: 35+) and religion (religious/spiritual vs. non-religious/non-spiritual). Other potential social identities, such as gender identity, nationality, ethnicity and social class, were excluded due to the large number of categories, making meaningful analysis challenging. The Kruskal–Wallis (KW) nonparametric test was chosen because it does not assume that the data follows a normal distribution (Ostertagová et al. 2014, p. 115). The KW Test was applied to questions where respondents provided Likert scale ratings or percentages. For Likert-scale questions, respondents rated categories on a scale from 0 to 5 (0—Not at all, 1—To a small extent, 2—To some extent, 3—To a moderate extent, 4—To a great extent, 5—To a very great extent). Responses categorized as ‘Other’ were excluded, as this category could encompass a diverse range of answers, which might obscure meaningful results. In some instances, the KW Test was supplemented with a post hoc analysis using homogeneous subsets. This approach identified specific factors that were statistically different or similar, and the results have been presented in the relevant graphs. The other statistical test used was the Crosstab Test to determine whether there is any statistical significance between observed and expected counts (i.e., number of respondents selecting a particular answer) between different characteristics of respondents.

For percentages and Likert scale values, the averages (means) and standard deviations (SD) are presented as graphs and tables. Averages were calculated from respondents who provided a figure and thus excluded missing data. While the mean and SD are not ideal for non-normal data, as ideally the median should be used as a measure of location rather than the mean and the range or percentiles for assessing variation, they are included to offer a visual sense of location and variation. SDs are displayed as ‘error bars’ on the graphs. Each summary table includes the mean (rounded to one decimal point), the KW Test (H statistic), the Cross Tab Test (Chi-square statistic), and the p-value for statistical significance. A 5% (0.05) cutoff point was used throughout to indicate statistical significance. This study adopts a sociological approach while also drawing particularly on insights from material culture studies and alternative disciplines such as anthropology, psychology, and esthetic theory offer valuable tools for interpreting art objects where relevant. Sociology provides a distinct focus on how meaning is constructed through social practices, identities, and everyday interactions. Posters, as cultural artifacts, are not only esthetic objects but are also embedded in social contexts, shaped by fandom, space, memory, and display. This study, therefore, privileges sociological frameworks to examine how owners attribute personal and collective significance to their posters.

The semi-structured interviews were recorded, and handwritten notes were taken. Any screenshots taken of the posters showing the participants interacting with them had their faces blurred, and the pictures were cropped to preserve anonymity. The recorded interviews were transcribed using ‘Otter’ (https://otter.ai, accessed on 7 May 2024) and manually reviewed for accuracy. Participants were assigned pseudonyms (e.g., Respondent 1) for confidentiality. Data from the online survey, including graphs and statistical tests, informed the content analysis of the interview transcripts. Open and axial coding was applied to the transcripts, notes, and survey responses to identify themes and highlight important quotes. Visual aids, such as photographs, floor plans, and video screenshots, were used to supplement and validate the notes.

3. Results

3.1. Poster Ownership, Content and Factors That Influenced Their Selection

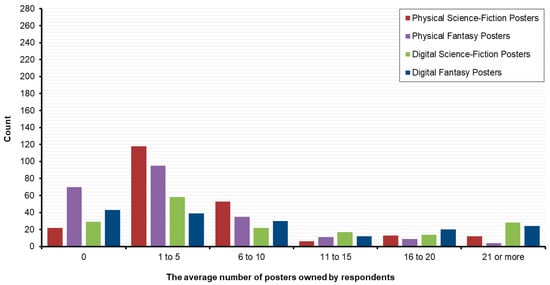

Most respondents owned both physical and digital posters, though physical posters were the dominant type. Respondents typically owned ‘1 to 5’ physical posters, while the highest number of posters owned was in the digital category, with ‘11 or more’ (Figure 1). This was unsurprising, as digital posters are easily accessible, require minimal storage space, and are not constrained by physical limitations. In contrast, physical posters were less accessible, occupy more storage or display space, and often competed with other objects for display space. In terms of the other analyses in this paper, no distinction will be made between physical and digital posters, nor between science fiction and fantasy as genres.

Figure 1.

The number of physical and digital science-fiction and/or fantasy poster(s) the respondents currently own.

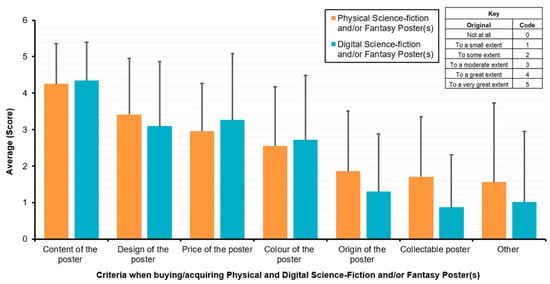

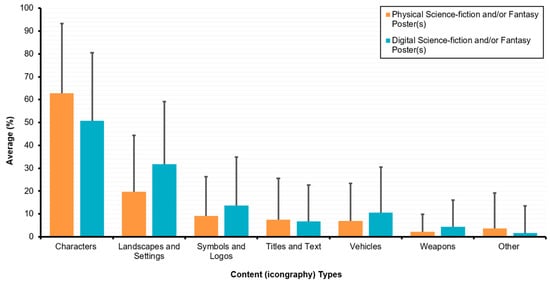

The visual characteristics of the posters were the most important factors influencing acquisition (Figure 2), with content and design ranking highest, followed closely by price. Color also appeared as a visual factor, though it was ranked slightly lower by respondents. In this paper, the term ‘The Big Three’ refers specifically to the intrinsic visual properties of the poster—its content, design, and color—rather than external variables like price, which are shaped by market availability, personal budget, and context. Price, while clearly important to decision-making, is not an inherent feature of the poster itself and thus falls outside this conceptual grouping. Nevertheless, their importance was approximately the same for both physical and digital posters. Of less importance when it came to acquiring them were the origin of the poster and whether it was a collectable. The content of posters owned by respondents predominantly featured characters, particularly in the case of physical posters (Figure 3). Landscapes and settings were the next most commonly depicted in terms of poster content and were more frequently found in digital posters. Other aspects, such as symbols, logos, text and vehicles featured less prominently in the posters owned by respondents.

Figure 2.

The importance of the criteria when buying/acquiring physical and digital science-fiction and/or fantasy poster(s), along with the SD (error bars). ‘Other’ is presented at the right-hand side to distinguish it from predefined criteria, as it consists of diverse participant-supplied responses rather than a singular variable.

Figure 3.

The average percentages of the primary content (iconography) of the respondent’s physical and digital science-fiction and/or fantasy poster(s), along with the SD (error bars). ‘Other’ is presented at the right-hand side to distinguish it from predefined criteria, as it consists of diverse participant-supplied responses rather than a singular variable.

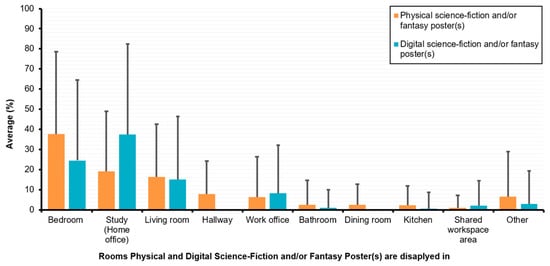

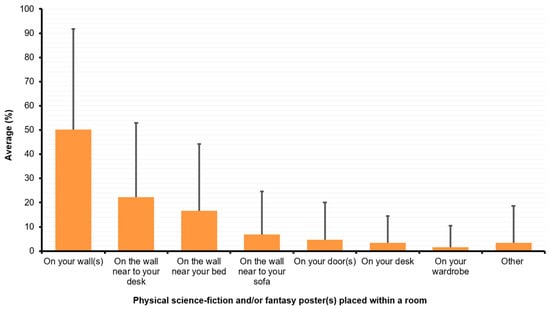

Respondents mostly displayed their posters in private spaces of the home (Figure 4). The bedroom was the most common place for physical posters to be displayed, followed by the study and the living room. For digital posters, the most frequent location was the study, presumably where computers were kept. Physical posters were typically displayed on the walls of a room, often near a desk, sofa, or bed (Figure 5). The importance of placing their physical posters was driven by three criteria: providing a better view of the poster(s), ensuring the poster fitted well with other posters or objects in the space and whether it brightened or added color to the room.

Figure 4.

The mean percentages in which rooms the respondents display their physical and/or digital science-fiction and/or fantasy poster(s), along with the SD (error bars). ‘Other’ is presented at the right-hand side to distinguish it from predefined criteria, as it consists of diverse participant-supplied responses rather than a singular variable.

Figure 5.

The mean percentages where the physical science-fiction and/or fantasy poster(s) placed within the respondent’s room(s), along with the SD (error bars). ‘General wall placement (‘on the wall(s)’) may overlap with specific wall locations, as participants could select multiple applicable responses. ‘Other’ is presented at the right-hand side to distinguish it from predefined criteria, as it consists of diverse participant-supplied responses rather than a singular variable.

3.2. Emotional and Identity Significance of Posters

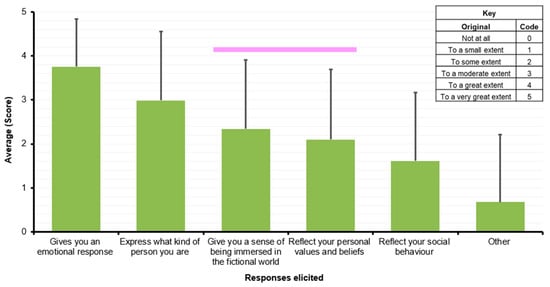

Respondents noted that their posters often elicited emotional responses (Figure 6 and Table 2). Among all demographic groups, female respondents were the most likely to report that their posters evoked emotional reactions compared to male respondents (Table 2; H = 10.17, p < 0.001). Age did not appear to have any significant effect on emotional response, although ‘religious identity’ (which included spiritual identity) was close to being statistically significant (p = 0.07), with those identifying as religious/spiritual scoring higher than those who did not. Similarly, in terms of expressing the ‘kind of person’ the respondent feels themselves to be there was also a significant difference between males and females, with females scoring this higher than males (H = 3.83 p < 0.001). However, and perhaps surprisingly, the extent to which SFF media posters provided a sense of immersion in fictional worlds was relatively limited and no statistically significant differences were found between the SAR groups in relation to feelings of immersion (Table 2). Given that the SFF genres are about the imagining of different worlds, it was anticipated that the posters would aid in a sense of immersion in those places, but this does not seem to be the case. Likewise, the degree to which posters reflected personal values was low, as shown by the average Likert scores in Table 2. Older respondents placed greater value on posters that reflected their personal beliefs and values compared to younger respondents (H = 4.64 p < 0.05), but for both groups, the Likert scores are relatively low. A similar pattern emerged regarding posters as reflections of social behavior, with this dimension also reported to a minimal extent. Again, no statistically significant differences were found between the SAR groups in relation to posters reflecting a number of different responses from their owners (Table 2).

Figure 6.

Responses elicited from posters on their owners. The bars are the mean Likert score along with the SD (error bars). The horizontal bar (Pink line) signifies a homogeneous sub-group (at p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Results of Kruskal–Wallis tests designed to explore the responses elicited from science fiction and fantasy posters for certain demographics. Shaded cells are those having statistically significant difference at p < 0.05. Note: ns = not significant at p > 0.05; * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001.

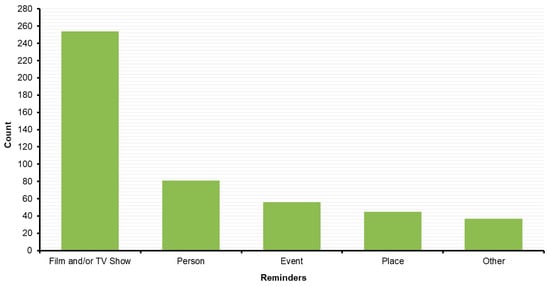

The results suggest that posters also serve as reminders, frequently triggering feelings of nostalgia, particularly for the films or television shows from which they originate (Figure 7). In addition, SFF media posters can evoke memories of people, events, and places, but the extent of this is far less than it is with the reminder of a movie or TV show. Notably, no statistically significant differences in pattern were found between any of the SAR groups regarding whether posters served as reminders (Table 3).

Figure 7.

Number of respondents who claimed that their posters provided reminders of a film and/or TV show, person, place, or event.

Table 3.

Results of contingency table statistical tests (Chi-square) to explore whether their poster(s) acted as reminders of a film and/or TV show, person, place, or event for certain demographic groups. Note: ns = not significant at p > 0.05.

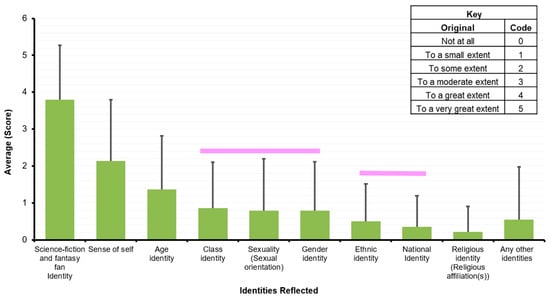

In terms of the interplay between posters and identity (Figure 8 and Table 4), the identity that was most strongly reflected was being a fan of SFF. There was no significant difference between any of the SAR groups in terms of the importance of SFF fan identity. The second most common identity reflected was a sense of self, with female respondents more likely to report that their posters expressed this dimension compared to males (H = 3.86 p < 0.05). For the most part, posters did not reflect, or only minimally reflected, other identities such as age, gender and religious/spiritual affiliation. However, while the Likert scores for these other identities were relatively low when compared to fan identity and a sense of self there were a few significant differences between SAR groups. Those expressing a religious/spiritual identity also regarded posters as more strongly reflecting a gender identity (H = 4.7 p < 0.05) than did respondents who said they were not religious or spiritual. Also, female (H = 4.76 p < 0.05) and younger respondents (H = 5.31 p < 0.05) were more likely to score higher than males and older groups when it came to posters reflecting sexuality.

Figure 8.

The extent to which respondents felt that posters reflected identities reflected. The bars are the average Likert scores along with the SD (error bars). The horizontal bars (Pink line) signify homogeneous sub-sets (at p < 0.05). ‘Any other identities’ is presented at the right-hand side to distinguish it from predefined criteria, as it consists of diverse participant-supplied responses rather than a singular variable.

Table 4.

Results of Kruskal–Wallis tests designed to explore the extent to which science fiction and fantasy posters reflected identities for various demographic groups. Shaded cells are those having statistically significant difference at p < 0.05. Note: ns = not significant at p > 0.05; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

In this study, “culture” refers to the shared meanings, practices, and values associated with fandom communities, while “fan culture” is understood as the collective identity and engagement practices through which individuals connect over science-fiction and fantasy media. While the survey focused on personal meanings, the interviews revealed how these are shaped by broader cultural narratives and fan-based interactions.

Furthermore, the survey treated elements like design and emotion or personal and cultural meaning separately, this was a practical choice to aid comprehension. The interviews revealed how these dimensions are in fact deeply interconnected, reflecting their complex theoretical entanglements. The results of the online survey provided pointers that were followed up in greater depth in the interviews. The prominence of characters within posters was of note (Figure 3) and the survey results did indeed suggest that posters elicited responses such as emotion (e.g., a feeling of happiness) and a sense of the kind of person the respondent thought themselves to be. They also reflected a sense of identity, especially in terms of their being a fan of SFF but also having a sense of self. What was more surprising was the relatively low score given to posters for providing a sense of immersion in the different worlds conveyed by SFF. While SFF media themselves can be highly immersive, the posters appear to function more as symbolic reminders of those texts rather than as direct conduits for immersive experience. As reflected in Figure 7, posters often serve as prompts for recalling movies and TV shows, rather than enabling immersion in their own right (Figure 6). This suggests that the cultural significance of SFF posters lies less in transporting viewers into fictional realms and more in how they operate as personal and esthetic markers of identity, memory, and fan affiliation. As these points were followed up in greater depth during the interviews, they will be referred to generically as ‘results’ in this section, and they will be related back to literature and relevant theories.

It first needs to be noted that results suggest SFF posters have three types of significance for their owners, namely ‘esthetics,’ ‘functionality,’ and ‘personal significance’ (which includes both personal meaning and connection to the media text). These aspects primarily influence how poster owners perceive their posters in terms of their significance, but also potentially how others may observe them when displayed. This is related to points made by Hebdige (1979, p. 3), who argued that objects within a subculture can hold dual meanings—both utilitarian (aligned with ‘functionality’ and ‘esthetics’) and symbolic (‘personal significance’). However, one of these significances can be more valuable or be the only valuable significance to their owner. After all, some poster owners, such as Respondent 26, said they did not seek an emotional response from their posters. Instead, they valued them for purely esthetic reasons, like matching the room’s color scheme.

While some owners derive deeper emotional or immersive value from collecting, displaying, and observing these posters, others appreciated them primarily for their visual appeal or the brief imaginative thoughts they inspire, without experiencing significant emotional resonance. Given the inherently imaginative nature of the SFF genres, it is perhaps unsurprising that some owners described their posters as fostering a sense of connection to the fictional worlds represented—through visual cues or thematic references—rather than evoking a direct emotional response. These three significances will be discussed in terms of preferences owners have in terms of their posters and placement, emotional response posters give their owners, and how posters reflect personal identity.

4.1. Choices, Choices

The results suggest that the type of poster, including its availability and components (such as content, design, and color), played a significant role in acquisition, with common elements consistently influencing owner preferences, as illustrated in Figure 2 providing an illustration). Indeed, when it came to the factors that influenced poster selection, two of ‘The Big Three’—content and design—were paramount. Price also played a role, but for respondents, it was clear that content and design mattered. One reason respondents often referred to regarding their choice of poster to display was their esthetic appeal, which can make owners happy simply because they are pleasing to look at. As Respondent 12 noted, posters are “like any form of quality artwork … pleasing to the eye and mind.” However, enjoyment can vary depending on the “subject matter,” and someone uninterested in a particular genre may not appreciate a poster “no matter how beautiful the painting or artwork is” (Respondent 12). Clearly posters can function as art, and “being able to surround yourself with art that you enjoy has some kind of positive effect on you” (Respondent 20). This adds value for individuals who “collect art … to display it, and to look at it themselves, and to enjoy its existence” (Respondent 20).

Physical posters tended to be displayed in bedrooms (Figure 4 and Figure 5), which is not surprising given that bedrooms are often the most personalized and frequently used spaces in the home (Dey and De Guzman 2006, p. 901). In contrast, more open or shared areas—such as living rooms, hallways, workspaces, and home offices—were secondary choices for poster placement. These shared spaces, particularly the living room, often serve a different function. As Rechavi (2009, p. 133) notes, the living room is typically used to express and communicate one’s self and social identity to others through the objects displayed within it. In the interviews it was clear that the location and placement of the posters contributed to their meaning, often having a symbiotic relationship with the space they occupied, thereby enhancing the significance of both the poster and the room. This can positively affect the owner, offering mental comfort and often receiving positive feedback from others. Ultimately, the owner’s preferences, such as content choice and placement, are crucial to the significance of the SFF poster.

4.2. Emotional Response

The results suggested that posters evoked emotional responses (Figure 6). For many of the SFF poster owners, although not all, eliciting an emotional response was an important factor in their connection to their posters. For some, this emotional engagement is a crucial aspect of their attachment, while for others, only specific posters evoked a meaningful reaction, often tied to personal experiences, nostalgia, or affinity with the media text they represent. As one participant reflected, fandom was “partly within my own personality”’ adding that removing a poster can signify a psychological shift: “it’s time to cut ties with something at that point” (Respondent 14). This supports Kadyrgali et al.’s (2024) assertion that “emotion is the most vital factor that connects the movie to the human”, which, in this context, extends to posters as emotionally resonant artifacts. Some owners expressed a need for their posters to continually elicit emotional reactions, not only at the time of acquisition but also upon repeated viewings—“the first time” to “the seventh time” (Respondent 24). However, emotional resonance may diminish over time as owners become desensitized or adapt to the constant presence of posters in their environment. Despite this, the presence of posters remains significant. For example, Respondent 21 noted that posters influence their overall “well-being and happiness,” while another participant stated that their absence led to negative emotional states, including feeling “trapped” and “isolated” (Respondent 9). Posters became a visual anchor during uncertain times, serving as a source of calm, a reminder of positive experiences, and creating a positive atmosphere, especially during difficult periods such as the COVID-19 pandemic, reminding them of better times. With those who lacked close relationships especially during social distancing, posters featuring characters, as indeed many of them did (Figure 3), became like “friends” (Respondent 3) offering companionship, a sense of reassurance and comfort This aligns with Wang’s (2019) argument regarding the importance of text on a movie poster in fostering emotional engagement; however, it contrasts with his assertion that text primarily serves as a marketing tool to sell the media text. This highlights the emotional and psychological impact posters can have on their owners and connects with McVeigh’s (2000, p. 266) concept of consumutopia, which he describes as a consumerist “counter-presence to mundane reality fueled by late capitalism, the pop culture industry, and consumerist desire”. ‘Consumutopia’ involves the consumption of objects that offer immersive, idealized fantasies, even if unattainable. McVeigh identifies five traits of consumutopic objects—ubiquity, accessibility, projectability, a unifying leitmotif, and contagious desire. In this context, posters display two of these: projectability, the ability of an object to absorb and reflect personal meaning; and contagious desire, the impulse to display meaningful objects to reinforce emotional connection and identity. This emotional investment reflects how owners encode significance into posters, which in turn shape their psychological state. Similarly, Appadurai (1986) argues that objects accrue meaning through social circulation; posters become meaningful not solely for their design, but for the fantasies and affective attachments they embody. Conversely, the absence of posters being displayed can result in negative feelings and supports Carney’s (1994) argument that art (or decorative objects) serves both emotional and cognitive roles for individuals and groups. However, some owners may avoid posters that “invoke a negative emotional response” as Respondent 6 explained, “I don’t think it’s very healthy or very good to be actively seeking out things that just are negatively impacting us”. One negative emotion that posters can elicit is “heartfelt sad emotion”, such as grief where the poster serves as a reminder that those who have passed but are “still with me” (Respondent 28). This may at first seem strange given that the characters in the SFF posters are, of course, fictional but fictional narratives can provide a safe space where audiences can experience a range of emotions without needing to act on them in real life (Smith 2022). Furthermore, Smith (2022) argues that emotional responses to fictional texts and real-life events are equally significant and legitimate, as fiction often draws from or refers to real-life elements or events.

Beyond the general emotional significance of posters, several respondents emphasized that the specific content—what the poster visually depicts—plays a critical role in shaping their emotional experience. For example, Respondent 28 noted that posters portraying a “good happy setting” contributed positively to their overall well-being. Owners often acquired posters that feature characters (Figure 3) and these gave more of an emotional engagement as they felt “a little bit more real with a lot of different emotions” (Respondent 28) and owners felt that they resonate with aspects of their personality (Figure 3). Posters featuring identifiable characters often strengthen the connection to the media text, and serve as reminders of the characters’ multifaceted nature, emphasizing their humanity and complexity. For Respondent 15, “characters that I have on my walls are touchstones for stories”, while landscapes are seen as “invitations to step into something new”. As shown in the summary provided in Figure 3, landscapes and settings were the second most frequently featured aspects of posters. Respondents noted an open-ended quality to these visuals that allowed them to imagine the rest of the narrative. This quality was perceived to add “more value” to the poster and made it something that was, in the words of Respondent 7, “what I enjoy looking at.” This further reinforces Chunyuan and Li’s (2021) argument that film posters transmit information through their visuals, shaping audiences’ emotional experiences. Nonetheless, the prevalence of characters in the posters aligns with the statement made in the documentary 24×36: A Movie About Movie Posters (2016) that studio-produced posters predominantly feature characters because “it’s a little bit easier to sell a movie by defaulting to the star face”. This reinforces Smith’s (2022, p. 54) argument that the emotional response to fiction is inherently ‘empathic’ and ‘sympathetic,’ as audiences form connections by engaging with the protagonist(s). Similarly, this emotional engagement can extend to poster owners and their connection to the characters depicted. This is supported by Välisalo’s (2017) study of audiences’ emotional responses to The Hobbit characters, which found that emotional reactions were strongly tied to the audience’s connection to the characters and the events depicted in the films.

For some, the emotional engagement with their posters was a crucial aspect of their attachment, while for others, only specific posters evoked a meaningful reaction, often tied to personal experiences, nostalgia, or affinity with the media text (the movie or TV show) they represent. These memories can relate to both the media texts themselves and the places where they were filmed. For example, Respondent 10 recounted a family holiday in New Zealand, where The Lord of the Rings was filmed. The Lord of the Rings poster reminded them of that trip, describing it as “one of the last times that we were together as a family” and reflected on it as a “good experience, a pleasant time”. This aligns with Money’s (2007) assertion that objects can possess embedded commemorative qualities. Additionally, it supports Frost et al. (2006, p. 24), who argue that movie posters serve as indicators of what owners “choose to remember,” whether that be their personal history or the historical significance of the poster itself. In this context, posters serve as prompts to elicit memories and experiences. As indicated by the survey results in Figure 7, posters can connect owners to the stories of the media texts they represent and evoke the emotions associated with the experience of first watching them. Respondent 11 explained that posters “take me to certain aspects of the story” and “give me feelings of specific areas of the story”. For instance, their fan art poster of the science fiction movie Serenity (2005) elicits a positive emotional response, giving them “warm feelings” as it reminds them of the story’s conclusion, where the characters survive the final battle and go on to live their lives. It is not the poster that does this per se but the poster as a vehicle for representing the movie. This strengthens Gray’s (2010) argument that posters act as paratexts of the media text, possessing synergistic elements that complement and enhance the media text without fully encapsulating it. Gray (2010, p. 52) describes posters as being “densely packed with meaning”, offering different dimensions of engagement. This also supports Tuan’s (1998, p. 194) and Gabbiadini et al.’s (2021) findings that engaging with SFF media texts can enable a sense of immersion even if this is not direct, and helps provide nuance to the, at first, surprising results shown for the importance of immersion in Figure 6. Furthermore, it expands Smith’s (2022) argument that a media text’s narrative elicits specific feelings and experiences in the audience, demonstrating that this can also apply to posters. Although respondents themselves did not conceptualize their posters as paratexts in Gray’s (2010) terms, their accounts imply that posters operate paratextually—providing visual cues that evoke specific scenes or characters from the broader narrative worlds of science fiction and fantasy media.

When it came to poster type influencing their well-being, a point hinted at by the online survey results but explored in greater depth in the interviews, physical posters held particular significance for some owners due to their tangible nature. Respondent 22 described physical posters as “tactile” and noted that being able to “look at it just feels more kind of real, like it’s more of a real presence in the world and a reminder of my connection to that”. Similarly, Respondent 12 highlighted the importance of a poster’s “bigger size and the tangibility of the object”. However, for others, the content of the poster was a more significant factor than its type. As Respondent 19 explained, “It’s the medium—it’s not important to me. It’s the content”. This suggests that while physical posters offer unique benefits relative to digital posters, the overall impact of a poster often lies in its subject matter. In addition, other objects, aside from posters, can also evoke emotional responses and serve as reminders of media texts. The presence, or absence, of such objects can affect mood, sense of self, and overall psychological well-being, demonstrating that posters function as more than just visual decoration; they are emotionally charged cultural artifacts embedded in everyday life.

4.3. Posters and Personal Identity

In many ways, the results suggested that SFF posters functioned as a form of self-expression, akin to other personally meaningful objects (Figure 6). They not only reflected individual interests and esthetic preferences but also served as markers of the owner’s SFF fan identity and sense of self (Figure 8). Posters carried significant “informational value”, as “each one [poster] communicates something” about its owner, even if it is simply a “reference” to what they “care about or enjoyed” (Respondent 20). Surrounding oneself with items like posters “help[ed] you cultivate who you are as a person in a way that you’re happy with” (Respondent 6). They also serve to “reflect” and “reaffirm” (Respondent 20) aspects of the owner’s identity when viewed. Indeed, the decision-making process when acquiring a poster often involves careful consideration regarding what it communicates about the owner even being “in some way is probably a very large element” (Respondent 20). Indeed, as Respondent 23 observed, “anything you purchase has a small reflection on you”, whether intentional or not. Decorating a space that they occupy allowed owners to “externalize” and maintain their self-identity, “even if I’m not consciously thinking about it when I get any given poster” (Respondent 20). For Respondent 15, posters go even deeper, serving as “an external representation of my internal mental landscape”, reflecting aspects of themselves that they “don’t have words for”. However, while the online survey did point to a broad link between posters and self-identity (Figure 8), the interviews suggested that a poster owner’s sense of self and how they identify who they are is highly subjective and varied greatly between individuals. Some of this is hinted at with the analysis of sense of self and the SAR groups in Table 4. Indeed, it strengthens the assertions of Isfandiyary (2017), Case (2009), and the Victoria and Albert Museum (2021) that “posters have been a vital means of communication” and one way that posters facilitate communication is through ‘silent conversations’ between owners and their possessions (Abram 1996). In this context, posters communicate key aspects of the owner’s identity, such as their values, interests, and sources of enjoyment, offering a non-verbal medium for self-expression and reflection. Posters provide an accessible way to “make these kinds of statements about oneself”, enabling others to “read what the posters say about me” (Respondent 20). Ideally, these statements convey something “moderately positive” (Respondent 25), offering others an opportunity to decide whether to pursue a relationship (Respondent 10). This reinforces Chadborn et al. (2017) argument that fan objects serve as tools for fostering positive social engagement, allowing individuals to express aspects of their identity and enabling others to interpret and respond to these self-representations. However, owners were aware that posters may also communicate something negative or unsettling to others. This supports Hall’s (1973) reception theory, particularly the concepts of ‘negotiated readings’ and ‘oppositional or resistant readings’ where the owner interprets the meaning of the poster in relation to aspects of their identity, while others might not fully agree or might reject the meaning altogether.

For some interviewees, posters may reaffirm specific aspects of their identity, such as being a SFF fan, rather than their entire sense of self. For Respondent 10, their interest in SFF is a core part of their identity: “It has shaped the sort of person I am… my values… and being open to exploring other ideas”. This supports Grossberg (1992) argument that being part of a fandom actively contributes to the construction of an individual’s identity. For instance, Respondent 23 stated that posters “definitely” reaffirm their identity as a sci-fi and fantasy fan because “they’re just such direct references”, thereby showcasing their passion for the genre; a point that reinforces Borer’s (2009, p. 1) and Frost et al.’s (2006, p. 24) argument that fans use objects to display and reflect their fandom. Respondent 28 described their posters as a way of “keeping it around, keeping me involved in the worlds and spaces created by the film or book”. This strengthens Poole and Poole (2013) assertion that movie poster collectors can “own a piece of the movie” in tangible form, serving as a lasting memento of the media text. Displaying a poster signifies that it has “passed the test” of suiting their tastes and reflects their sci-fi and fantasy identity (Respondent 22). These findings reinforce recent research suggesting that fan identity affirmation leads to increased engagement, demonstrating the affirmative significance that the fantasy genre and fandom can have in fans’ lives (Groene and Hettinger 2016).

Posters communicate various aspects of their owners—such as personal interests, fandom affiliations, and emotional attachments—and often serve as symbolic expressions of identity (Respondent 11). However, participants also acknowledged the limitations of using posters to fully convey their beliefs or personality traits, suggesting that meaning is not fixed or universally understood. This dynamic reflects Hall’s (1973) encoding/decoding model, which theorizes that media texts are encoded with intended meanings by producers, but those meanings are subject to negotiation or resistance by audiences based on their social and cultural frameworks. In this context, poster owners may ‘encode’ their self-expression into the posters they choose to display, yet they remain aware that others may interpret these displays differently. For example, a poster that represents nostalgia for one viewer might be read as trivial or decorative by another. Such interpretations align with Hall’s notion of negotiated readings, where meaning is partially accepted but reinterpreted, or oppositional readings, where the viewer rejects the intended message entirely. Thus, the act of displaying a poster becomes an inherently communicative and interpretive process, shaped by both personal intent and audience perception.

For some of the interviewees, posters served as a means of expressing their convictions and reflected their beliefs, opinions, philosophies, values, and what was important to them. Posters can communicate what matters most to their owner and conversely, they may avoid displaying anything that contrasts with their beliefs. Respondent 24 noted that their posters conveyed their “philosophy as a human” and what they “value”. These choices also serve to non-verbally signal to others that they are “welcome here” (Respondent 15) and to foster connections with like-minded individuals (Respondent 19). This supports Habermas’s (1991) argument that spaces within the home grant owners the agency and control to personalize and decorate their environment. By encoding their posters with significance, owners can create a positive ambience and atmosphere.

On the other hand, some owners derive value from nostalgia, and their posters were “just a picture on a wall” (Respondent 25) rather than reflecting their identity. This suggests that while posters can reinforce identity for some, others may find their primary significance in the emotional connections they evoke.

4.4. Into the Future

Perhaps understandably, most existing research on media posters has focused on their commercial role as advertisements, but this study approached them from a different perspective. Additionally, while there is extensive literature on media posters, little has specifically examined the SFF genres. A key message emerging from this research is that SFF posters hold significant meaning for their owners, and the findings contribute to fandom studies and material culture research by demonstrating that SFF posters are more than just advertisements for media texts—they can indeed carry deep personal and cultural significance. However, while the research has pointed to many aspects of the relationships between SFF posters and their owners, there is much more that needs to be explored.

Firstly, it does need to be noted that the COVID-19 pandemic-imposed restrictions on in-person data collection prevented interviews in the spaces where SFF posters were displayed. It also made other potential methods, such as focus groups and event-based observations (such as at conventions or makeshift SFF poster stalls), unfeasible. Future research should conduct in-person interviews in participants’ homes, observe individuals acquiring SFF posters in real-time, and engage with SFF poster artists, retailers, and convention sellers to gain additional insights.

Secondly, while many countries have their own movie industries, and the SFF genres have had multiple cross-influences, this research was focused on respondents domiciled in Europe and North America; respondents from these places accounted for over 70% of the total number of respondents. It is possible, indeed likely, that applying the same research methodology set out here with fans living outside these locations could generate different results. This would be an intriguing study. However, even if the research is extended to other socio-cultural contexts, it would be necessary to employ a stratified sampling approach to ensure representation across key demographic variables, such as nationality, age, gender, and socioeconomic background.

Thirdly, a longitudinal study tracking the social and cultural lifecycle of an SFF poster, from acquisition to ownership, display, and possible storage or disposal, would provide deeper insights into the evolving significance of posters over time. This could help tease out the long-term dynamics of poster ownership and display. Indeed, one approach may be to focus on such a lifecycle-based analysis for a specific media text, such as the Star Wars franchise, given its long-running (since the 1970s) legacy and presence across multiple media formats, including books and games.

Fourthly, another future study that focuses on the communal aspect of collecting posters rather than the individual poster ownership in this study could be considered. This was found in this study as some interviewees did discuss others seeing/showing and having conversations about their posters. There are online communities, conventions, and collector forums where poster value is debated and displayed.

Fifthly, another study could explore in greater depth the fan hierarchies of taste in terms of posters. This was briefly touched upon in this study in terms of poster ownership, but more depth could generate interesting results. Notions of value extended beyond financial worth to possibly include emotional resonance, rarity, official status, association with specific eras or films, older posters and teaser posters. For example, older posters could be described as “authentic” or “special” due to their age, original print status, or connection to formative viewing experiences.

Sixthly, a study could explore how the nostalgic affective dimension is central to poster significance. In this study, some interviewees stated that their posters evoked nostalgia, were often framed as mnemonic devices, reminding participants not only of the films themselves but of the life stages when those films were first encountered. Another form of nostalgia for owners could be the components of the poster itself. For example, posters with dated design styles (e.g., hand-drawn illustrations or vintage typography) evoked a strong sense of period, contributing to their perceived authenticity and emotional appeal. Perhaps collecting older posters could be a way of “preserving” owners’ media history, reinforcing the idea that fan collections are archives of self and memory.

Finally, a study could explore the evolution of poster esthetics and how this esthetic shift may influence collecting practices. The comparison between earlier iconic posters (e.g., Jaws) that have minimalism, symbolic power, and uniqueness and recent posters that have an ensemble-cast design with high-saturation color palettes and dramatic symmetry (e.g., Endgame) further illustrates how poster design reflects broader industrial and esthetic trends. Exploring this evolution of poster esthetics in relation to collecting practices would be intriguing.

5. Conclusions

This research yielded several key conclusions which emerged from this research, and these are summarized as follows:

- SFF posters held deep significance and meaning for their owners, often resonating with special occasions, serving as reminders of the media text, and contributing to the personal importance of their spaces. The significance and meaning of SFF posters stemmed from two key conceptual frameworks: ‘The Three Significances’—esthetics, functionality, and significance (space or personal significance)—and ‘The Big Three’—content, design, and color.

- SFF posters functioned as a form of self-expression, reflecting their owners’ identities, affinities, and convictions. This was primarily achieved through the content of the poster and its connection to the referenced media text.

- SFF posters primarily reflected and reinforced their owners’ self-perception rather than their moral beliefs. One of the main motivations for acquiring posters was their ability to affirm fan identity, which owners viewed as a significant part of who they are. Beyond identity reinforcement, posters also provided joy and personal satisfaction.

- The space in which SFF posters were displayed shaped their meaning and significance, just as posters influence the atmosphere and function of a space. Unlike more conventional decorative objects, posters are often perceived as niche, leading to greater negotiation over their placement, typically resulting in their display within personal spaces such as bedrooms.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/socsci14070443/s1, Supplementary Material S1 (structure of online survey); Supplementary Material S2 (structure of semi-structured interviews).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declara-tion of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Brunel University London (First round: 23185-LR-May/2021-32581-2 and 6 May 2021; Second round: 23185-A-Jul/2022-40641-1 and 14 July 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon reasonable re-quest from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical reasons.

Acknowledgments

I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to the staff at College of Business, Arts and Social Sciences Department, for their invaluable support, guidance, and encouragement throughout this research. I also want to sincerely thank all the participants who took part in the online survey and interviews. Their willingness to share their experiences and insights allowed me to explore the incredible world of science-fiction and fantasy film and television posters and their potential significance.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CGI | Computer-generated imagery |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease |

| df | Degrees of Freedom |

| H | Kruskal–Wallis Test statistic |

| JISC | Joint Information Systems Committee |

| SAR | Sex, Age and Religion |

| MCU | Marvel Cinematic Universe |

| N | Total number of responses |

| n.d | No date |

| n.p. | No page number |

| P | Probability |

| SD | Standard Deviations |

| SFF | Science-fiction and fantasy |

| Sig. | Statistical significance |

| TV | Television |

| V&A | Victoria and Albert |

References

- 24×36: A Movie About Movie Posters. 2016. [Documentary] Directed by Kevin Burke. Los Angeles and Morin-Heights: Snowfort PicturesPost and No Joes Productions. [Google Scholar]

- Abram, David. 1996. Part II: Maurice Merleau-Ponty and the participatory nature of perception. In The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than-Human World. Edited by David Abram. New York: Vintage Books, pp. 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai, Arjun. 1986. Introduction: Commodities and the Politics of Value. In The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Edited by Arjun Appadurai. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 3–63. [Google Scholar]

- Belk, Russell W. 1988. Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research 15: 139–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, Harold P. 2011. The psychological birth of art: A psychoanalytic approach to prehistoric cave art. International Forum of Psychoanalysis 20: 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borer, Michal Ian. 2009. Negotiating the symbols of gendered sports fandom. Social Psychology Quarterly 72: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, Ray. 2004. Conversations with Ray Bradbury. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. [Google Scholar]

- Broderick, Damien. 2003. New wave and backlash: 1960–1980. In The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction. Edited by Edward James and Mendlesohn Farah. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 48–63. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Therese, and Joanna Patching. 2021. Mobile methods: Altering research data collection methods during COVID-19 and the unexpected benefits. Collegian 28: 143–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, Kerman, Ester Bejarano, and Ignacio de Loyola González-Salgado. 2024. Interviews that heal: Situated resilience and the adaptation of qualitative interviewing during lockdowns. In Transformations in Social Science Research Methods During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Edited by J. Micheal Ryan, Visanich Valeria and Brändle Gaspar. London and New York: Taylor & Francis, pp. 121–37. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Joseph, and Bill Moyers. 1991. The Power of Myth. New York: Anchor. [Google Scholar]

- Canavan, Gerry, and Eric Carl Link. 2019. On Not Defining Science Fiction: An Introduction. In The Cambridge History of Science Fiction. Edited by Gerry Canavan and Eric Carl Link. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Carney, James D. 1994. A Historical Theory of Art Criticism. Journal of Aesthetic Education 28: 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, Donald O. 2009. Serial collecting as leisure, and coin collecting in particular. Library Trends 57: 729–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadborn, David, Patrick Edwards, and Stephen Reysen. 2017. Displaying fan identity to make friends. Intensities: The Journal of Cult Media 9: 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yunru, and Xiaofang Gao. 2013. Interpretation of movie posters from the perspective of multimodal discourse analysis. GSTF International Journal on Education 1: 76–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chunyuan, Liu, and Liu Li. 2021. Research on the Application of Cultural Symbol Digitization in Movie Poster Design. Paper presented at 3rd International Conference on Energy Resources and Sustainable Development (ICERSD 2020), E3S Web of Conferences, Harbin, China, December 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dawsons Auctions. 2024. How Do I Know if My Film Poster Is Valuable? Available online: https://www.dawsonsauctions.co.uk/news-item/how-do-i-know-if-my-film-poster-is-valuable/#:~:text=What%20determines%20the%20value%20of%20a%20poster%3F&text=Chances%20are%2C%20the%20rarer%20the,the%20chance%20of%20higher%20value (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Dey, Anind K., and Ed S. De Guzman. 2006. From awareness to connectedness; the design and deployment of presence displays. Paper presented at the 2006 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI 2006, Montréal, QC, Canada, April 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, Mathew. 2017. Historicising Transmedia Storytelling-Early Twentieth-Century Transmedia. New York: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, Malcom, Angharad Lewis, and Aldan Winterburn. 2006. The Rise and Fall of the Poster—Street Talk. Victoria: The Images Publishing Group Pty Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Gabbiadini, Alessandro, Cristina Baldissarri, Roberta Rosa Valtorta, Federica Durante, and Silvia Mari. 2021. Loneliness, escapism, and identification with media characters: An exploration of the psychological factors underlying binge-watching tendency. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 785970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, Jonathan. 2010. Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers, and Other Media Paratexts. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Groene, Samantha L., and Vanessa E. Hettinger. 2016. Are You ‘Fan’ Enough? The Role of Identity in Media Fandoms. Psychology of Popular Media Culture 5: 234–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossberg, Lawrence. 1992. Is there a fan in the house? The affective sensibility of fandom. In The Adoring Audience: Fan Culture and Popular Media. Edited by Lisa A. Lewis. London: Routledge, pp. 50–65. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Junger. 1991. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Stuart. 1973. Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse. Birmingham: Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, Occasional Papers, No. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Hebdige, Dick. 1979. Subculture. New York: Methuen. [Google Scholar]

- IMDb. 2024. Jaws. Available online: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0073195/?ref_=tt_mv_close (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Isfandiyary, Farah Hanum. 2017. The Aspects of Semiotics Using Barthes’s Theory on a Series of Unfortunate Events Movie Poster. Ph.D. dissertation, Diponegoro University, Semarang, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Henry. 1992. Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kadyrgali, Elnara, Adilet Yerkin, Yerdauit Torekhan, and Pakizar Shamoi. 2024. Group Movie Selection using Multi-channel Emotion Recognition. Paper presented at 2024 IEEE AITU: Digital Generation, Astana, Kazakhstan, April 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, Ruth Nadelman. 1983. Fantasy for Children. An Annotated Checklist and Reference Guide, 2nd ed. New York: R. R. Bowker. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, Catherine, and Gretchen B. Rossman. 2014. Designing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, Richard. 2002. Fantasy: The Liberation of Imagination. New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- McVeigh, Brian J. 2000. How Hello Kitty Commodifies the Cute, Cool and Camp: ‘Consumutopia’ versus ‘Control’ in Japan. Journal of Material Culture 5: 225–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Rui, and Xiaohui Shen. 2021. Research on Fonts in the Design of Movie Posters. Paper presented at 7th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2021), Online, May 25–26. [Google Scholar]

- Money, Annemarie. 2007. Material Culture and the Living Room The appropriation and use of goods in everyday life. Journal of Consumer Culture 7: 319–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, Katherine M. 2017. Gender and fandoms: From spectors to social audiences. In The Routledge Companion to Cinema & Gender. Edited by Kristin Lené Hole, Dijana Jelača, E. Ann Kaplan and Patrice Petro. Oxon: Routledge, pp. 352–60. [Google Scholar]

- Naderifar, Mahin, Hamideh Goli, and Fereshteh Ghaljaie. 2017. Snowball sampling: A purposeful method of sampling in qualitative research. Strides in Development of Medical Education 14: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olympia Publishers. 2024. Science Fiction: The Genre of the Future. Available online: https://olympiapublishers.com/blog/science-fiction-the-genre-of-the-future/ (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Ostertagová, Eva, Oskar Ostertag, and Jozef Kováč. 2014. Methodology and application of the Kruskal-Wallis test. Applied Mechanics and Materials 611: 115–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]