1. Introduction

The concept of quality of life (QOL) is closely tied to lifestyle—its planning, experience, and subjective fulfillment. While definitions of QOL vary, common themes include personal goals, satisfaction, and contextual wellbeing. Emerson (in

Felce and Perry 1995) identifies QOL as the satisfaction of personal goals and lifestyle needs. The

World Health Organization (

1995) frames it as an individual’s perception of their position in life, within a cultural, value, and societal context.

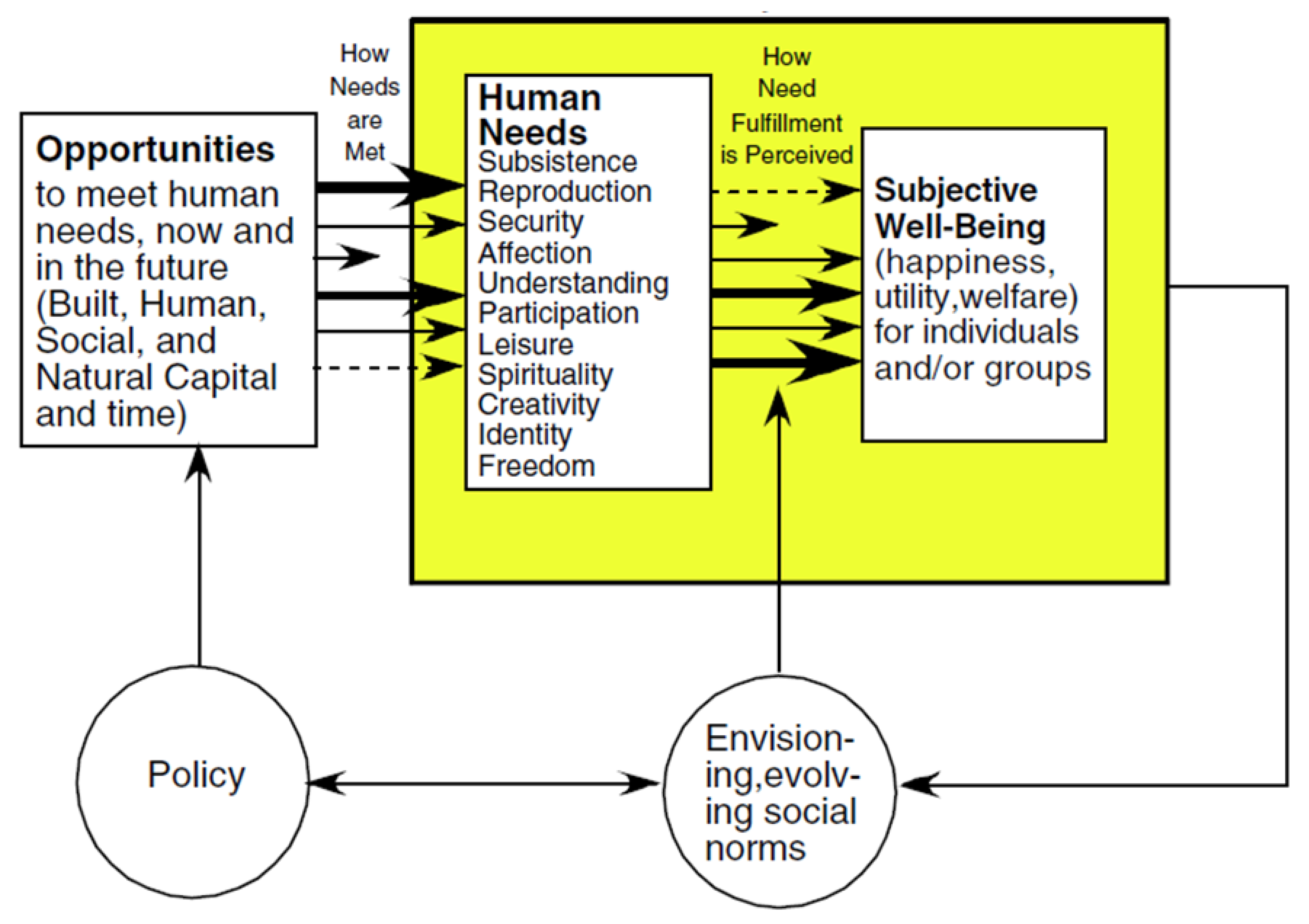

Costanza et al. (

2007) emphasize the interaction between objective human needs and subjective well-being, highlighting the role of perception in fulfilling these needs (

Figure 1).

Massam (

2002) further adds that QOL is influenced by an individual’s living conditions and environment. Additionally, many researchers (

Tay et al. 2014) have observed a positive relationship between religiosity and indicators of wellbeing such as self-esteem, happiness, and life satisfaction. These connections form the foundational basis for this study’s exploration of QOL in relation to ethical values and religious attitudes, particularly within the educational context.

In Slovakia, the post-communist transformation significantly impacted the national educational framework. Since 2004, following an intergovernmental treaty with the Vatican, the Slovak education system has integrated both ethics and religious education into public school curricula. This dual-track model respects student choice and aligns with the principle of equal opportunity in national educational policy. Religion is not limited to theological instruction but is understood as a broader value system that guides moral reasoning and civic behavior (

Weil et al. 2023).

Historically, education has embodied both intellectual and moral aims, often considered sacred or “religium”—a Latin-rooted concept implying reverence and commitment.

Komorovský (

1994) interprets religium as a general human attitude that binds individuals to deeply respected ideals, whether religious, philosophical, or scientific. This outlook supports the idea that education is more than the transmission of knowledge; it is a formative process grounded in ethical and cultural values. Education plays a central role in shaping society by preparing individuals not only for economic participation but also for meaningful and responsible citizenship.

Education, and especially its theory—didactics, has always been something untouchable and sacred—religium in every period. The word religium was often associated only with the field of religion (religion, etc.). The term religium has a much broader content and needs to be more fully defined (

Vanolo 2013). Religium can be understood as a generally human attitude by which a person declares his relationship to the object of his interest. Everything that is respectable and what one perceives as serious or essential for one’s life becomes a religion (

Komorovský 1994). Education is therefore a process that contribute to consolidating the stability of society and its changes (development) and at the same time condition the way it exists by mediating the transmission of knowledge, cultural values and traditions of previous generations. In this context, moral values—as expressions of both ethical principles and religious beliefs—become central to the educational process. According to

Weil et al. (

2023), education should cultivate literacy and moral awareness. Morality and ethics, when supported by religious or spiritual commitments, serve as a basis for individual dignity, tolerance, and responsibility. This study therefore focuses on the impact of moral and religious education on adults’ perceptions of quality of life, particularly how values instilled during schooling influence life satisfaction and social behavior.

Education is an integral part of national culture. The values that are created in education are the future bearers, creators and users of culture. That is why cultural life—education, science, art, religion—must have a special emphasis in society. Education should include an understanding of the nature of human dignity, personal freedom, value, the individual, the right to be responsible for oneself and for others, respect for the value of human life, tolerance of other ways of life, the value of the law, religious freedom etc. (

Poulos 2019). Therefore, positive life values should be formed within education. Religion or more precisely another system of values should be taught as a guide to moral decision-making and the justification of personal morality. Religion plays a central role in shaping human behaviour. Religious beliefs influence a number of economic and demographic outcomes, including employment, marriage, and fertility (

Lehrer 2008).

Fox (

2004) analyses the role of religious ties in the spread of ethnic conflict across borders.

Toft (

2007) explore distinction between whether religion plays a peripheral or central role in armed conflicts. We cite these examples to justify the definition of ethical principles as moral values, but in the context of Slovak educational policy also as religious values (respecting the students choice of the selection of ethics/religion subject). The authors define these values as ethical values for the purpose of the study.

But nowadays, according to

Kaur (

2015), everywhere crime flourishes. We see corruption. People are unaware of the truth. Jealousy has become the overall base of life. But if the citizens are healthy, patriotic, honest, and sincere, the nation will progress at a much faster pace. For this reason, it is very essential to have education based on ethical values in schools and colleges (

Warnecke et al. 2019).

In this article, on wellbeing and contribution of moral education and development of ethical values on quality of life in adulthood, we begin by considering definitions of quality of life, moral values and their importance for quality of life perception.

Because if human values take root in the educational system, the emerging individuals will have the following attributes: They will want peace & justice in the world; Freedom and self-reliance to be available to all.

The dignity and work of every person to be recognized & safeguarded; All people to be given an opportunity to achieve their best in life; and They will seek equality before the law and the equality of opportunity for all (

Parab 2015). The interest in quality of life has become characteristic of contemporary modern society.

Pacione (

2003) defines that “quality is not an attribute contained (directly) in the environment, but is a function of the interaction between environmental characteristics and personal characteristics (human)”, whereby it is stated that in most cases the meaning of the term quality of life refers either to the conditions in which people live or to certain attributes of the people themselves. The terminological expression of both basic dimensions of quality of life are the concepts of environmental quality (

Chen 2023) and human well-being. Since the end of the 20th century, but especially at the beginning of the 21st century, aspects of sustainable development have become an integral part of the concept of quality of life. Quality of life as a concept is differently understood from the point of view of psychology, medicine or sociology. The sociological perception of quality of life emphasizes the signs of social success, which are status, property, household equipment, marital status and education. An important concept is the standard of living, i.e., the quality and quantity of services and goods that people have available. In medicine, the emphasis is on assessing the quality of life in the field of psychosomatic and physical health. The quality of life influenced by health is used here (

Švehlíková and Heretik 2008).

Romney et al. (

1994) state some reasons why there is no generally accepted definition of quality of life:

- –

psychological processes relevant to survival (feelings of quality of life can be described and interpreted through many different conceptual filters and languages),

- –

the concept of quality of life is largely influenced by value laden,

- –

the concept of quality of life includes an understanding of the processes of human development, the living space of an individual and the extent to which his internal psychological processes are influenced by environmental factors and the individual value system (

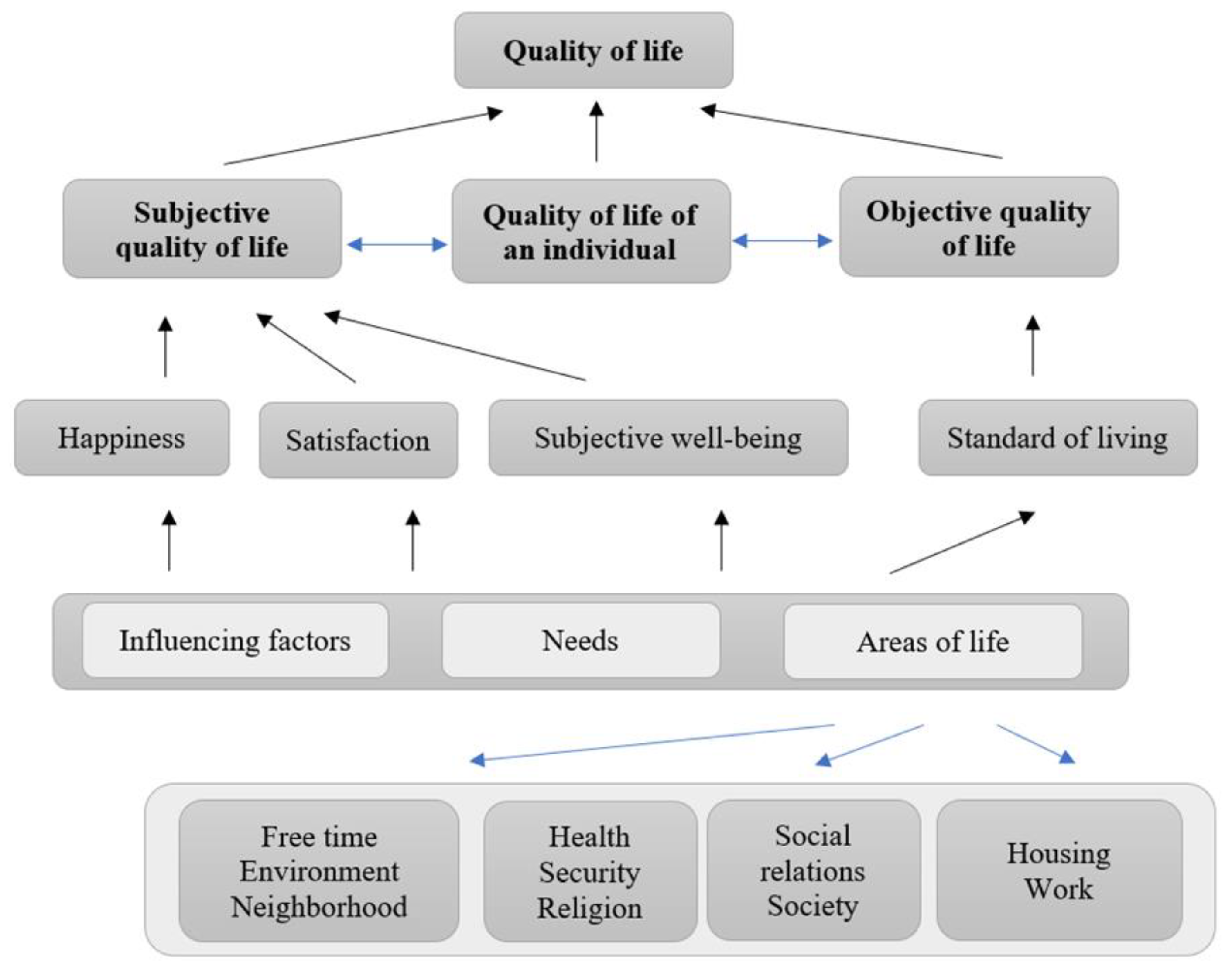

Fadhel et al. 2024). The research is framed within a multidimensional understanding of QOL. Scholars such as

Pacione (

2003),

Cummins (

1997), and

Štofková and Štofko (

2016) highlight that QOL includes both subjective perceptions and objective conditions, ranging from health and employment to spirituality and social relationships. This study aligns with that integrated view by investigating how subjective perceptions of QOL are shaped by exposure to moral and religious education during youth (

Figure 2).

Ultimately, the goal is to assess whether ethical values and religious attitudes fostered through education influence adults’ subjective evaluations of their lives, and to what extent these values contribute to societal wellbeing. This inquiry is particularly relevant in Slovakia, where ethical and religious instruction co-exist within the school system, offering a unique opportunity to study their long-term impact.

Within the subjective perception of quality of life, we talk about the following areas:

in general/objective indicator is the level of living standards, subjective satisfaction with life/

health/objective is the degree of physical health, subjective satisfaction with health/

work/object indicator is the length of employment and absence at work, subjective satisfaction with work/

family/objective is the length of marriage and cash spent together, subjective satisfaction with marriage and family/

society/objective indicators are educational institutions, leisure time, opportunities for cultural activities, crime, the state of the environment, infrastructure and subjective satisfaction with the environment and offers/

housing/objective indicator is supply of electricity, gas, housing conditions, subjective satisfaction with housing/

education/objective indicator e.g., level of education, availability, quality of education and subjective satisfaction with one’s own education/

Subjective attributes of quality of life, or so-called individual quality of life is according to

Diener and Suh (

1997), also related to the notion of subjective well-being in the sense of the sum of cognitive and affective reactions of a person to the conditions of his life. In addition to his moods or emotions, they also consider his satisfaction with life to be a part of a person’s subjective well-being.

The objective dimension of quality of life then represents the (external) conditions and influences of the surrounding environment and living circumstances on human life, which in most cases tend to be divided into social, economic and environmental (

Gajdoš and Ručinský 2010).

The issue of quality of life indicators overlaps in many respects with the issue of quality of life areas, as indicators are the basic means of their evaluation. The choice of research areas, in turn, indicates which indicators will be used in it. The interrelationship between the two issues is also confirmed by

Pacione (

2003), who points out that the set of selected indicators must be broad enough to cover all of the most important areas of human life.

Despite interdisciplinary efforts in quality of life research, so far the results of cooperation between different scientific disciplines have not reached the expected level.

Our goal in the present study is to focus on the subjective perception of objective indicators, specifically their influence by passing religion within educational curricula, which according to

Pacione (

2003) will allow in particular:

- –

understanding the structure, dependencies and relationships of different areas of human life,

- –

understanding how, by combining feelings about different areas of one’s life, one forms an overall assessment of one’s quality of life,

- –

understanding the causes and conditions leading to an individual feeling of well-being and the effects of these effects on human behavior,

- –

identification of issues deserving of special attention and, where appropriate, social interventions.

Specifically, this means indicators used worldwide to measure the rise or fall in living standards, specifically the Social Progress Index.

The Importance of Ethical Values for Quality of Life (Moral Ethics and Religion Attitude)

The main principle of educational policy is considered by the Government of the Slovak Republic to be equal opportunities for all young people, regardless of the social situation, region or ethnicity, and orientation to the needs of children, pupils and youth. In 2004, Slovakia signed an intergovernmental treaty with the Vatican, in which, in addition to other privileges, it undertook to provide the Catholic Church with space to teach the basics of the Christian faith from the first year. The right to teach religion in state schools is held by state-registered churches, so in addition to the dominant Catholicism, in the case of a sufficient number of interested people, we can also encounter Orthodoxy or Evangelism in schools. While religion can offer valuable moral frameworks, existential orientation, and a sense of community, its role in education—particularly in pluralistic or secular societies—raises important challenges. Religious education, whether confessional or non-confessional, must respect the freedom of belief and conscience of all students. In increasingly diverse classrooms, not all students share the same religious background, and some may identify as non-religious. If not carefully framed, religious content may risk marginalizing certain students or reinforcing dominant cultural norms. Moreover, religious language and concepts may not be equally accessible to all learners, potentially limiting their engagement. Scholars have warned that without a critical, inclusive, and dialogical approach, religious education can become dogmatic or exclusionary (

Jackson 2004;

Gearon 2013). Therefore, integrating religion in education demands a pedagogical sensitivity that balances the potential benefits of moral and spiritual formation with the ethical obligation to foster autonomy, critical thinking, and mutual respect among all learners.

One of the goals of teaching not only ethics, but also Christianity in state primary and secondary schools is a kind of educating young people in the spirit of Christian values. It aims to “prepare and activate children for life in society and educate them to make them conscious and responsible citizens with high moral credit” (

Nagranová 2012). Values and value systems are transmitted by various social institutions, and the function of such institution is undoubtedly held by ethics or religious belief. In his study, criminologist B. Johnson points out that there is a relationship between ethics, religion and the moral values of the individual. The report says that most delinquent crimes are committed by young people with a low level of ethical commitment, especially in the absence of religious belief. For example, people who were followers of a church became a delinquent with much less frequency (In

Abun and Cajindos 2012).

Arruñada (

2010) and

Chadi and Krapf (

2017), argue about social ethics and compliance with uniform rules laid out in culture, or more precisely religious denomination, what we consider a main driver of citizens’ values. Both Arruñada and Chadi and Krapf show that German Catholics are more likely than German Protestants to consider tax fraud as morally justifiable. In the same direction, they observe greater willingness of Catholics to cover up rule-cheating friends. Overall, Catholics are more protective of their personal relations, including their families, but less willing to contribute to solving public good problems at a community or institutional level. Focusing on country differences hides these differences and precludes attempts to develop institutionally well-suited solutions. According to functional theory, religion is inevitable for every society because it is a form of human behaviour that helps maintain the social system. According to O’Dea, religion provides an orientation towards something that is outside the everyday world (In

Nešpor and Lužný 2007). The basic function of religion is its integrative function.

Lewis lists three levels of moral significance:

ensuring harmony between individuals,

helping to form good people and good societies,

maintaining a good relationship with a Creature that has a creative character.

The third level indicates that man’s faith is a decisive element for moral behaviour, it is a necessary precondition for it. This means that the most important predicate of an individual’s moral behaviour may be religious commitment (In

Abun and Cajindos 2012). The idea that morality must have an absolute basis and that this absolute basis is God has been expressed many times in the history of religious-philosophical thinking. Ralph Cudworth, an 18th-century Cambridge platonic, argued in his controversy with Hobbes that a moral law can only be important to man if it originates in something absolute, necessary, i.e., in God’s mind.

Cohen (

2014) adds that non-God-based moral laws are without authority, a fact that could have an adverse effect on society as a whole. Morality unsupported by “force majeure” causes a kind of disappearance of decency from human society and thus logically worsens the subjective perception of quality of life.

The EU is very open to the educational process, supports any education that promotes moral and ethical values (ethical, religious education) and fights against education that evokes any kind of hatred (racial, religious, etc.). Teaching religious education, even outside the EU, can be:

- -

compulsory: Austria, Romania, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Greece, United Kingdom, Germany, Switzerland,

- -

optional: Slovakia, Czech Republic, Poland, Australia, Belgium, Spain, Portugal, Baltics, Hungary,

- -

In the Slovak context, the dual-subject system—where students may choose between religious education and ethics—creates a unique framework for value transmission. However, this system requires critical pedagogical reflection. A growing body of literature in the field of religious and values education (

Jackson 2004;

Schreiner 2011;

Bertram-Troost et al. 2007) stresses the importance of distinguishing between confessional and non-confessional approaches in schooling. Confessional models aim at religious socialization, while non-confessional approaches focus on dialogical engagement with diverse value systems and ethical reasoning (

Hanesová 2005b).

Didactic theory emphasizes that the transmission of values should be sensitive to the pluralistic composition of classrooms, students’ developmental stages, and individual value orientations (

Schweitzer 2014;

Heimlich 2016). The educational process should move beyond the mere inculcation of normative content, and instead create space for reflective, student-centered learning about moral and religious dimensions of life. As

Bleeck (

2013) and

Franck and Béraud (

2019) argue, effective values education must incorporate the principles of critical thinking, dialogicity, and personal meaning-making. These principles are particularly important in post-secular contexts like Slovakia, where religion is not only a private matter but also a cultural and political reality.

From a didactic perspective, values education should aim at moral literacy—the capacity to engage in moral reasoning and ethical judgment—rather than simply teaching students “what is right.” This aligns with the views of Kohlberg’s moral development theory (1981), which emphasizes the importance of developmental stages in ethical reasoning, and with the concept of Bildung as a transformative educational process. In this sense, religion or ethics in education function not only as conveyors of tradition, but also as pedagogical spaces for dialogue, reflection, and the shaping of moral identity (

Miedema and Bertram-Troost 2008).

Thus, the present study responds to educational science by framing moral and religious education as part of a broader didactic and pedagogical challenge: how to mediate values in a culturally sensitive and developmentally appropriate way that supports the formation of individuals capable of meaningful, responsible, and value-oriented lives.

2. Materials and Methods

The main aim of this paper is to evaluate the impact of selected personal characteristics on one’s perceptions regarding the quality of one’s life (within the selected criteria). As stated above, the Slovak Republic underperforms within the European countries in some areas of interest. We carried out this research and analysis within the surveyed target group in the months of April, May, June 2022. We carried out a random selection in a designated target group, which consisted of graduates of secondary or higher education at age maximum of 30 years. We assume that if we define youth according to

Smolík (

2010), it is a socio-demographic group of the population aged 15 to 30 with characteristic features, specific interests and requirements, value orientations, etc., which distinguish it from other age groups. At the same time, it is not a homogeneous group: its attitudes, interests and requirements depend primarily on the affiliation of young people to the social group (which we divided into subsamples due to chosen identification characteristics). During this period, young people integrate into the world of work, acquire social norms and requirements, shape the worldview, and start a family. Taking into account at the same time for the purpose of the research the established criteria of completed at least secondary school education, we consider target group aged 19–30 years. The research was carried out using a questionnaire method in eight regional cities of the Slovak Republic. We contacted a total of 1200 respondents (150 from each region), while evaluating the questionnaires we obtained 906 full-fledged forms.

When defining questions related to personal background, we determined six dominant identifying characteristics of respondents with respect to their affiliation to a selected subgroup formed within the target research group (for the purpose of researching statistics marked as subsample within the mail research sample). For the purposes of comparison, we defined the quiescent problem of research (related to main hypothesis H1) and six research questions (closely related to the hypotheses H1.1–H1.6). We chose six criteria due to the assumption of different perceptions of quality of life in young respondents according to the identification characteristics—i.e., the affiliation to the defined subsample. In defining these identification criteria, we used the study of

Butoracová Šindleryová et al. (

2019). These criteria were as follows: inclusion of the respondent in the subsample according to upbringing and education in an ethical or religious way (1), gender (2): male/female, level of education achieved (3): secondary education/university degree, current working position (4): employed/unemployed/student, place of living (5): urban/rural and marital status (6): single/married/divorced/widowed. The identified criteria are marked for research purposes as variables (V) and are marked numerically corresponding to the identification question in the questionnaire, i.e., education in an ethical or religious way (V1), gender (V2), level of education achieved (V3), current working position (V4), place of living (V5) and marital status (V6). Other questions of the questionnaire were designed to correspond to selected research areas of subjective and objective perception of quality of life by respondents. With regard to statistical comparisons of the social progress index for the Slovak Republic for 2021, we defined the key differences in the perception of life quality of youth in comparison with other researched countries with values defined as continuous declining or not improving (examining the score 2021, 2020, 2019)—these are within the individual monitored areas as follows:

Foundations of well-being:

Access to Basic Knowledge: Access to quality education (q7, q8, q9), primarily school enrollment (q10, q11, q12)

Access to Information and Communications: Access to online governance (q13, q14, q15)

Environmental quality: Greenhouse gas emissions (q16, q17, q18), Outdoor airpollution attributable deaths (q19, q20, q21)

Opprotunity:

Personal Rights: Freedom of religion (q22, q23, q24)

Personal Freedom and Choice: Corruption (q25, q26, q27)

Inclusiveness: Discrimination and violence against minorities (q28, q29, q30)

The numerical designation of the individual indicators is linked to the questionnaire questions assigned to them, for example questions No. 7, 8, 9 (q7, q8, q9) reflect the indicator “Access to quality education” within the questionnaire. We did not take into account in research those areas of quality of life and indicators in which the Slovak Republic overperformes in comparison with other European countries or statistically developes in positive numbers in relation to the European ratio.

Since the sample that was used here is not very diverse, we were able to provide an exact and specific hypotheses, which are relevant to all selected criteria comparison. While analyzing data, certain question was considered: Are there differences in the objective and subjective perception of quality of life in the selected criteria of youth respondents in relation to their identifying characteristics? The perception of the respondent’s affiliation to one of the defined subsample will affect the perception of quality of life in the defined six areas (upbringing and education in an ethical or religious way, gender, level of achieved education, current working position, place of living or marital status)? As the Slovak Republic Education Programme considers the subject of Ethics or Religion as compulsory subject in the National Education Programme, we suppose the criteria of upbringing and education in an ethical or religious way would be the most significant one.

Hypothesis H1: We assume that there are differences in the respondents’ perception of quality of life in selected criteria in relation to the identification characteristics of the respondent.

Basic Hypothesis H1.1: We assume that there are differences in the respondents’ perception of quality of life in selected criteria in connection with upbringing and education in an ethical or religious way.

Basic Hypothesis H1.2: We assume that there are differences in the respondents’ perception of quality of life in selected criteria in relation to gender.

Basic Hypothesis H1.3: We assume that there are differences in the respondents’ perception of quality of life in selected criteria in relation to the level of education achieved.

Basic Hypothesis H1.4: We assume that there are differences in the respondents’ perception of quality of life in selected criteria in relation to the current working position.

Basic Hypothesis H1.5: We assume that there are differences in the respondents’ perception of quality of life in selected criteria in relation to the place of living.

Basic Hypothesis H1.6: We assume that there are differences in the respondents’ perception of quality of life in selected criteria in relation to marital status.

In the research, we used the method of Spearman correlation with respect to a pair of ordinal variables (on a scale of 1–5, which values reflect absolute agreement, agreement, neutral response, disagreement, absolute disagreement). The results of the research were processed in the statistical program SPSS (version IBM SPSS Statistics 27).

The sample matrix was interpreted as a tool to visualize the composition of respondents based on key identifying variables (ethical/religious education, gender, education level, employment status, residence type, and marital status). These demographic characteristics were used to create subsamples that allowed for detailed correlation analysis. This analytical structure enabled the authors to explore how specific personal traits influenced perceptions of quality of life across domains such as education access, corruption, religious freedom, and environmental conditions.

3. Results

Our intention in this study is to examine the influence of ethical education (ethics/religion) and other factors on the perception of some attributes of quality of life by young people. In our opinion, ethical or religious education can play its inspiring role in the regionalization of the quality of life of young people.

Questions related to personal background were given not only for demographic data, but also for their use as the independent variables for the research comparison. We present the partial results statistically trying to present the structure of the subcultural groups of respondents within the main sample, we refer to these groups as subsamples (

Table 1).

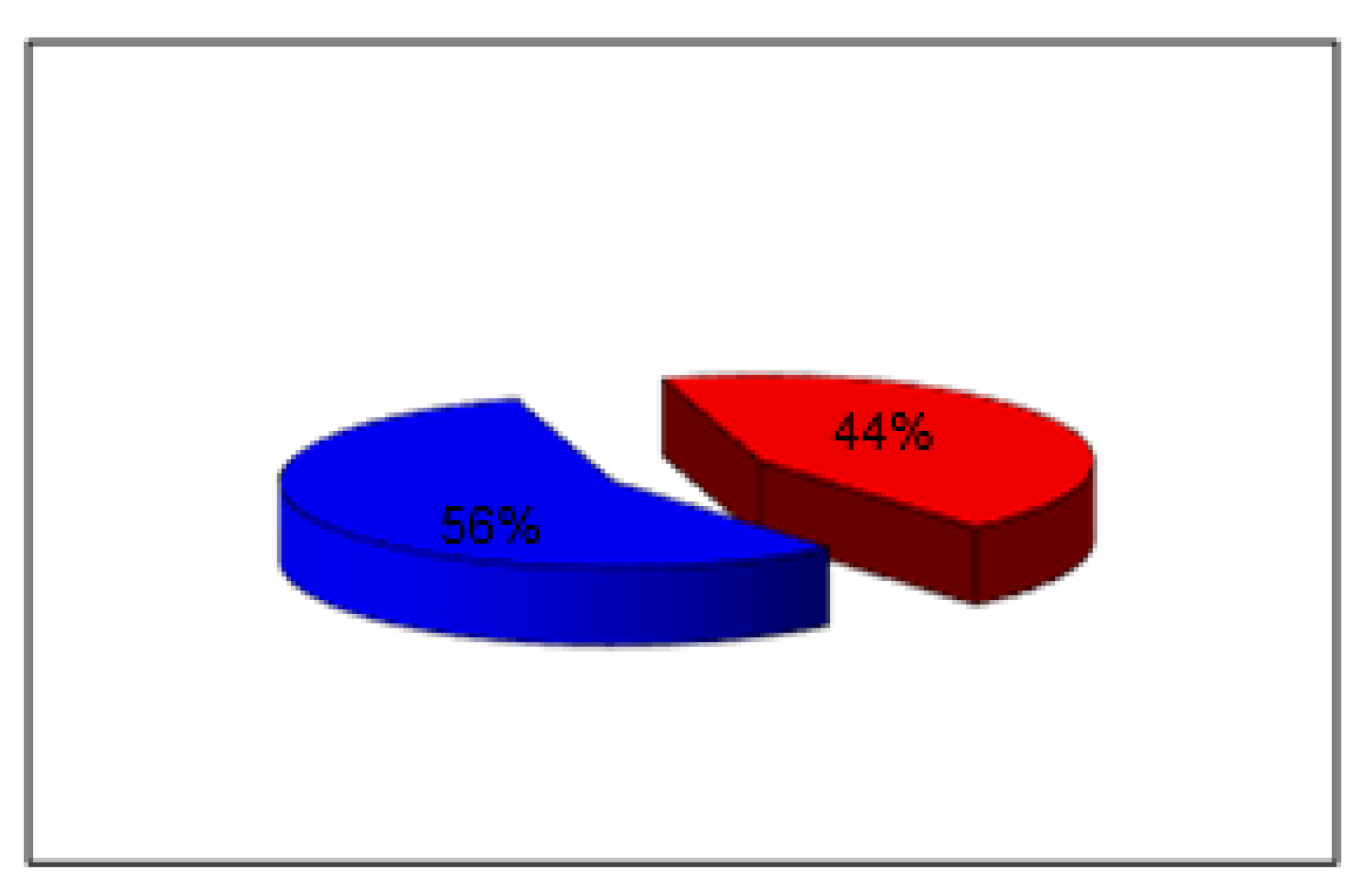

As expected, roughly half of the young people in the sample were raised up and continuously educated in an ethical way, similarly in a religious way, quite typical for a Slovak family and school environment. We suppose main differences would show up within this subsample, as the historically based religious principles seem to be least flexible to natural life changes and these principles do not allow even slight violations of moral principles and ethics (

Figure 3).

As might be seen in the chart above, the structure of respondents due to gender is quite similar. The sample is divided into two main groups: 395 female respondents and 511 male respondents.

The sample of 906 respondents is divided into two main subsamples, 617 respondents achieved university degree. That was quite expected because of social preferences of families to provide the young generation with the highest education. The structure of the sample due to the current working position/status of the respondents is shown in the table below (

Table 2).

As might be seen, most of the young people prefer urban style of living and stay single till their thirties. This might be a valuable variable for the next research, as these preferences influence their perception of quality of life in many criteria (

Table 3 and

Table 4).

Given the nature of the target group defined as the youth sample, we assumed that most of the respondents would be single (aged 19–30 years) (

Table 4 and

Table 5).

After identifying individual subsamples and their internal structure, we proceeded to correlation analysis. Correlations were calculated between items V1, V2, V3, V4, V5 and V6 (independent variables reflecting identifying questions q1, q2, q3, q4, q5 and q6 of the questionnaire) and items q7–q30 (questionnaire questions reflecting eight selected quality areas life in which the Slovak Republic either underperforms or declines within the average of the European Union indicators). The outputs of the statistical calculations are presented in a contingency

Table 6.

4. Discussion

Our empirical research among university students and young people under 30 in the Slovak Republic has led to some interesting findings that address the questions based on this study: What is the understanding of young people’s quality of life attributes? To what extent are they influenced by education based on the principles of either ethics or religion?

Significantly high values of the Spearman correlation coefficient in the indicators “Corruption” and “Freedom of religion” and a positive direct connection within the surveyed subsample brought up in religious way Corruption is a topic that has resonated very strongly in Slovakia in recent years and, specifically for religiously based people, represents an absolutely negative element of quality of life, the root of enslavement, unemployment, disrespect for the common good and nature. This fact also explains the important connection of the mentioned indicators with the education based on ethical or religious principles, because the inability to fight corruption represents for many respondents as an inability to enforce religious-ethical values and thus a kind of non-freedom in religion. We have a significant connection with the perception of these two areas, even in “Corruption” the level of significance is statistically significant at the level of α < 0.01, which is a very significant connection. Although the proven connection with the indicator “Discrimination and violence against minorities” is manifested, the values of the correlation coefficient R are relatively low and therefore this connection is not so dominant. This is probably due to the fact that the respondents were taught moral principles as students, primarily focused on tolerance and a willingness to help and protect. Within the subsample “gender” in the diversification of female and male young person there is a direct connection with the perception of quality of life of young people, especially in the selected area “Access to Basic Knowledge: Access to quality education” amplified by the fact that religiously based women and men are at the same time usually family-based and therefore want to create the best conditions for their future children, including the availability of quality education. At the same time, ethically or religiously based young men and women want to provide for their families, for which they inevitably need quality education today. Although the partial hypothesis H1.5 established on the given sample was confirmed, it is necessary to take into account the fact that the significance of this connection is quite low and we attribute it to it to me next. Our empirical research among university students and young people under 30 in the Slovak Republic has led to some interesting findings that address the questions based on this study: What is the understanding of young people’s quality of life attributes? To what extent are they influenced by education based on the principles of either ethics or religion?

Significantly high values of the Spearman correlation coefficient were identified for the indicators “Corruption” and “Freedom of Religion” in the subsample of participants raised in a religious way. Corruption is a topic that has resonated strongly in Slovakia in recent years, especially following high-profile political scandals (

Fazekas and Tóth 2016), and religiously inclined individuals often perceive it as a fundamental violation of moral principles. For many of them, corruption symbolizes the failure of moral systems, the erosion of respect for the common good, and a threat to societal well-being (

Koechlin 2013). This interpretation is consistent with educational psychology findings that emphasize the impact of value-based education on moral development and civic responsibility (

Nucci and Narvaez 2008).

This also explains the observed connection between education based on ethical or religious principles and sensitivity to corruption. For religious youth, corruption may also be interpreted as an inability to assert ethical-religious values in society, which is perceived as a form of moral and religious disempowerment (

Heath 2014). The significant correlation with the indicator “Freedom of Religion” suggests that youth educated in an ethical or religious way are particularly sensitive to constraints on belief systems and personal expression—consistent with the concept of “moral identity” as described by

Aquino and Reed (

2002).

Although a statistically significant connection was also found with the indicator “Discrimination and violence against minorities”, the correlation coefficients were relatively low. This may be explained by the fact that students were taught moral principles emphasizing tolerance and protection of the vulnerable—central tenets in both secular ethics education and religious moral frameworks (

Lickona 1991;

Berkowitz and Bier 2005).

In the “gender” subsample, a direct connection was found with the perception of the area “Access to Basic Knowledge: Access to quality education.” This can be linked to findings in gender studies showing that educational aspirations among young women and men are often shaped by future-oriented concerns such as providing for a family (

Eccles 2009). Young people with religious or ethical upbringing may prioritize education not only as a personal goal but also as a moral responsibility tied to their future family roles.

Although the “level of education achieved” criterion was related to the perception of “Access to Basic Knowledge,” the correlation values were relatively low. Moreover, a negative correlation was found with “Primary School Enrollment,” which raises questions about the interpretive strength of this relationship. Slovakia’s OECD position in educational quality and its high rate of students studying abroad may explain this result. Slovak youth often do not consider local access to education as a key life quality factor, instead prioritizing study abroad for its added value—language acquisition and life experience (

Altbach and Knight 2007).

The correlation between the “place of living” criterion (urban vs. rural) and perceptions of “Greenhouse gas emissions” and “Outdoor air pollution attributable deaths” was statistically significant but weak (R values close to zero). This low strength suggests that while the environmental agenda is relevant to youth (

Cincera et al. 2019), it may be seen more as a societal obligation than an individual quality-of-life determinant. Contemporary youth, influenced by global ecological discourse, view environmental protection as a collective responsibility rather than a personal preference (

Kagawa 2007).

For the criterion “current working position,” no significant correlation with perceived quality-of-life areas was found. Likewise, marital status did not influence quality-of-life perception among youth under 30. These findings align with sociological studies showing that younger generations are postponing marriage and long-term employment commitments in favor of autonomy and exploration (

Arnett 2004;

Roseneil and Budgeon 2004). Many young people today prioritize personal freedom and flexibility over traditional life paths, which reduces the weight of employment or marital status in their evaluation of well-being.

5. Conclusions

Our empirical research among university students and young people under 30 in the Slovak Republic yielded valuable insights into two core questions: How do young people understand the attributes of quality of life? And to what extent are these influenced by education grounded in either ethical or religious principles?

A significant outcome of the analysis was the strong Spearman correlation observed for the indicators “Corruption” and “Freedom of Religion,” particularly within the subsample raised in a religious context. Corruption, a critical socio-political issue in Slovakia (

Chmielewska and Horváthová 2016), is perceived by religiously educated respondents as an antithesis to core moral values. These individuals often associate corruption with systemic injustice, moral decay, and as an impediment to the realization of a just society aligned with spiritual principles (

Arruñada 2010;

Chadi and Krapf 2017). The statistically significant correlation (

p < 0.01) thus suggests that religious or ethical education may foster heightened moral sensitivity and intolerance toward unethical practices, such as corruption.

The study also explored the perception of the indicator “Discrimination and violence against minorities.” While a relationship was detected, the relatively low correlation coefficient indicates a weaker association. This may be attributable to the dominant focus of value education in Slovakia on tolerance, respect, and non-violence (

Butoracová Šindleryová et al. 2019;

Mihálik et al. 2018). These findings align with the research of

Brinkerhoff and Mackie (

1985), who noted a link between religious instruction and positive attitudes toward social equity and protection of the vulnerable.

Gender-based analysis revealed a positive association between young people’s perception of quality of life and the criterion “Access to Basic Knowledge,” especially among respondents with a religious upbringing. This corresponds with the findings of

Lehrer (

2008), who observed that religious commitment often motivates long-term goals, including family life and intergenerational educational aspirations. Our results suggest that religiously oriented youth—both men and women—view quality education as a prerequisite for providing for future families and contributing to society.

However, while the variable “level of education achieved” correlated with the perception of “Access to Basic Knowledge,” the correlation coefficient was low. Furthermore, there was a negative correlation with the criterion “Primary School Enrollment,” despite the hypothesis H1.3 being confirmed. This paradox may be explained by the growing trend of Slovak youth pursuing higher education abroad, driven by dissatisfaction with domestic education quality and the pursuit of linguistic and cultural capital (

Dissart and Deller 2000).

In terms of geographical context, urban/rural residence correlated significantly, though weakly, with environmental quality indicators such as “Greenhouse gas emissions” and “Outdoor air pollution attributable deaths.” This supports prior findings that environmental consciousness is increasingly integrated into youth value systems (

Chen 2023;

Costanza et al. 2007). While hypothesis H1.5 was technically confirmed, the weak correlations suggest that environmental quality may be perceived more as a societal responsibility than as an individual concern impacting subjective well-being.

The variables “current working position” and “marital status” showed no statistically significant relationship with perceived quality of life. This is consistent with prior sociological research noting that young people under 30, especially in post-industrial societies, often deprioritize marriage and stable employment in favor of autonomy, mobility, and fluid identity formation (

Oberuč and Zapletal 2017). These shifting social values may explain the absence of significant correlation between these variables and subjective quality of life.

Overall, these results align with the broader theoretical framework on quality of life as a multidimensional construct combining subjective well-being, moral values, and sociocultural context (

Cummins 1997;

Diener and Suh 1997;

Massam 2002). They also reflect the influence of value transmission through education (

Cohen-Zada and Elder 2018) and support the idea that religious and ethical instruction may play a role in shaping youth attitudes towards societal issues—thereby contributing indirectly to quality of life assessments.