Abstract

In 2023, there were approximately 32 million refugees globally. Nine out of the ten countries with the highest origins of refugees were in the Global South; conversely, only three of the ten countries hosting the highest numbers of refugees were in the Global North. In this study, we introduce the conceptual framework of a global division of responsibility sharing to describe how functions of Global North countries as permanent “resettlement” countries and Global South countries as perpetual countries of “asylum” and “transit” constitute unequal burdens with unequal protections for refugees. We illustrate—theoretically and empirically—how the structural positions of state actors in a global network introduce and reify a global division in refugee flows. Empirically, we test and develop this framework with network analysis of refugee flows to countries of asylum from 1990 to 2015 in addition to employing data on monetary donations to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) from 2017 to 2021. We (1) provide evidence of the structure and role of intermediary countries in refugee flows and (2) examine how UNHCR monetary aid conditions intermediary countries’ role of routing and transit. We illustrate how network constraints and monetary donations affect and constitute a global division in the management of historic and contemporary international refugee flows and explore the consequences of this global division for refugees’ access to resources and social and human rights.

1. Introduction

In 2023, there were approximately 32 million refugees globally, a record high that has continued to increase. Nine out of the ten countries with the highest origins of refugees were in the Global South; conversely, only three of the ten countries hosting the highest numbers of refugees were in the Global North. The question we might ask is: Why? The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is the organization mandated to help refugees, defined in the 1951 Geneva Convention and its 1967 Protocol as people residing outside of their country of nationality who are unable or unwilling to return because of a “well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.” But the UNHCR is also a “principal actor” in world politics, with 16,803 staff and an annual budget over USD 6.54 billion (Hamlin 2021; Loescher 2001). In an appeal to donor states in the Global North, the UNHCR has promised to support Global North state preferences for containment of refugees and refugee services in the Global South (Arar 2017, p. 300; Hamlin 2021).

Despite increased sovereignty for Global South states under the “new grand compromise” of refugee protections, which emphasizes how major hosting states can “leverage the value of their refugee hosting capacity and renegotiate policies to promote state-centric agendas” (Arar 2017, p. 298), containment and prioritization of Global North sovereignty remains evident today in the concentration of refugee services and flows (Hamlin 2021). The responsibility for hosting refugees and containing displacement disproportionately lies on major host countries in the Global South (Devictor et al. 2021; Hamlin 2021), where refugees often experience long stays, barriers to permanent legal status, a lack of social and economic integration and rights, poor governance, and insecurity (UNHCR 2024). In both Global South and Global North contexts, state governments increasingly adopt xenophobic and racialized policies to limit entry, domestic support, and permanent settlement for refugees, with negative consequences for the everyday well-being and interactions of refugees within local communities (Campbell 2006; Hassan 2000; Weng and Choi 2021). Given local and national xenophobia and racism, the absence of both global surveillance over refugee conditions and rights, and inequitable pathways to resettlement (Watson 2023), refugees often seek better opportunities by attempting longer, more circuitous, and more dangerous routes to reach safe third countries (UNHCR 2024).

We situate refugee flows and UNHCR donations within theoretical frameworks of world systems, the “new grand compromise” of refugee protection, and refugee and migrant network analyses to introduce the concept of a global division of responsibility sharing. Despite the “new grand compromise” of refugee protections in which states in the Global South have increased leverage (Arar 2017), we argue that an unequal division of responsibility sharing persists in refugee flows by analyzing monetary donations. Reflecting the shift in refugee protections after 2015, we test and develop this concept empirically using network analysis of refugee flows to countries of asylum from 1990 to 2015 and include data on UNHCR donations from 2017 to 2021.

Burgeoning research on refugee policies and flows between regions of origin and refuge illustrates how the UNHCR “prioritizes the sovereignty of states in the Global North at the expense of sovereignty of the Global South” (Arar 2017, p. 300; Hamlin 2021). Yet, there is little systematic empirical research about the consequences of these relational structures for refugee flows over time. We thus ask: How are refugee flows shaped by UNHCR spending and hierarchical core-periphery structures that shape dynamics between the Global North and Global South? We (1) provide evidence of how refugees are routed to countries of asylum that occupy a central intermediary position in a hierarchical core-periphery network structure; and (2) find that prospects of refugee flows are associated with UNHCR donations. Through analyzing the network structure of top refugee flows and how they are conditioned by monetary donations, this paper expands understandings of refugee systems and patterns over time and offers a conceptual and empirical model to explain how unequal burdens and unequal refugee protections between the Global South and Global North contribute to whether top refugee flows do or do not exist between countries.

2. Theoretical Framework

World-systems theory introduces an interdisciplinary approach to examine how historical and economic characteristics of a state translate into a country’s positionality in a relational framework (Wallerstein 2004). Theoretically, these characteristics shape states’ positions in the world-economy as economically stronger (core) or weaker (periphery) than others; semiperipheral countries are uniquely situated between core and peripheral countries (Wallerstein 2004). In migration studies, a world-systems approach views international migration as “a structural consequence of the expansion of markets within a global political hierarchy” (Portes and Walton 1981). At the same time, historic and current core country interventions in the periphery can also explain migration from the periphery to the core (Portes and Walton 1981).

World-systems theory provides a helpful framework for explaining the relational and political hierarchy of international migration but is less directly applicable to theorize refugee flows. However, the “grand compromise” of refugee protection (Cuéller 2006) highlights the “global political hierarchy” in refugee protection and state sovereignty, in which Global North states have traditionally held greater power than Global South states to control refugee flows (Portes and Walton 1981), similar to the core–periphery division of world-systems theory. In this grand compromise, states in the Global North pay money to the UNHCR, with the funds then directed to ensure refugee protections in host countries in the Global South; this relational hierarchy thereby aims to protect Global North states’ borders and security interests, and it limits refugee flows out of the Global South (Arar 2017). However, Arar (2017) theorizes that the unprecedented refugee flows to Europe in 2015 and 2016 constitute a “new grand compromise” and structure for refugee protections. As Europe sought to deter refugee arrivals, Global South states faced greater responsibility in refugee hosting, but they also gained additional sovereignty and leverage given their role as host countries (Arar 2017). For example, UNHCR aid for refugees in Jordan was paired with aid for development, infrastructure, and open trade agreements to the benefit of Jordanians and the Jordanian economy (Arar 2017). While this new grand compromise did include greater economic integration for refugees and increased leverage from states in the Global South, the preexisting structural characterizations of Global South and Global North states remained largely the same (Arar 2017).

Theories of network analysis complement the characterizations of Global South and Global North states in the management and protection of refugees. Network theory highlights how the decisions made by any one state are made within a relational structure characterized by the attributes of each country, the ties to other countries, and the relationships that characterize those ties. While a state maintains direct control of national policies, processes, institutions, and decisions about who they decide to label as refugees, and when they open, close, or externalize their borders (see Abdelaaty 2021; Hamlin 2021), this control is embedded in an interdependent and global network. How geographic neighbors and global institutions manage flows are equally important (Cook-Martín and FitzGerald 2019; FitzGerald 2019; Hamlin 2021; Hooks 2020). Thus, flows—the observable movements of refugees—occur within and are conditioned by stable and enduring structures: the relative positionalities among states that are differentially positioned across a global network. Political sociologists have built a strong theoretical framework highlighting the importance of global and regional hierarchies in shaping migration flows and state immigration policy (FitzGerald 2019; FitzGerald and Cook-Martin 2014; Garavini 2007; Patel 2021). Yet, few have examined how network structures and positionalities constrain and enable international refugee flows.

Network analysis has revealed the hierarchical structure of migrant flows. We extend these insights into the flow of refugees, who sometimes utilize the same routes (UNHCR 2024). Hooghe et al. (2008) found that network structures, center–periphery connections, and economic incentives shaped migrant inflows to Europe between 1980 and 2004. In empirical analysis of global migration between 1960 and 2000, Özden et al. (2011) found additional support for hierarchical migration patterns, with the United States, Western Europe, and the Gulf as the most important destinations for migrants. In Paul’s (2011) theory of stepwise migration, network externalities serve as a means of social facilitation and information sharing for migrants obtaining work visas and permissions. This analytic approach situates migration flows as a multi-step and hierarchical process of intermediate countries that link “here,” “there,” and states that fall in between. For refugees fleeing political and environmental threats in their home countries or poor governance and insecurity in host countries, this network structure becomes especially important to ensure safety from direct and immediate threats by facilitating intermediate stops.

The geographic diversity of refugee origins and the multiple steps refugees take mean that refugees cross multiple “second” countries (countries between the origin and destination). Network theory allows us to examine ties between countries through refugee flows, identify structural positions among states, and investigate whether and how certain states serve as intermediary stops or “routing points” along the migration journey. We discuss routing points as intermediary states positioned to bridge clusters of origin and destination countries and occupy strategic positions within the global refugee network. Routing points can be understood through the concept of bridging “structural holes” in network theory (Burt 2004) when states act as a broker between distinct segments of origin, transit, and destination states. States between loosely connected clusters, such as between Europe and sub-Saharan Africa, may leverage their role by negotiating better financial or political support from international actors. This highlights how certain states strategically negotiate their bridging roles for leverage, reflecting a level of embeddedness (Granovetter 1985) in refugee networks by controlling flows or refugees as a primary intermediary country.

In existing studies of refugee flows, country-level characteristics and meso-level migration networks translate into hierarchies in migration destination among individual migrants and shape the “autonomy of asylum” (De Genova et al. 2018). Data from asylum-seeker destinations in Western Europe in the 1980s and 1990s indicate that receiving countries that are geographically closer and share the same spoken language as origin countries receive more asylum seekers, as do countries where a high share of co-national asylum seekers already reside (Neumayer 2004). A qualitative study of Palestinian refugees from Syria in 2017 found that refugees utilized social networks to determine where they could acquire citizenship and prioritized destination countries accordingly, with Sweden as the prime destination (Tucker 2018).

To analyze refugee flows, we explicitly distinguish between the relational positions of countries within a global network, captured by a measure of centrality using intermediary status, and flows, actual refugee movement. We utilize world-systems, grand compromise, and network theories to question how state characteristics and the grand compromise historically contributed to refugee flows and whether the new grand compromise has altered these flows. We extend on prior scholarship on refugee governance by explicitly testing the previously theorized structural advantages and roles of intermediary states. By leveraging disaggregated UNHCR donor data available after 2017, we test whether the new grand compromise and its impacts on states in the Global South have also stabilized, altered, or encouraged new network structures of flows after 2017. Our analysis thus contributes theoretically and empirically by understanding the conditions under which routing points emerge or stabilize, and by detailing the structural positions states have by bridging otherwise loosely connected segments of the global network.

3. Hypothesis

Research on migration flows demonstrates how countries in the Global North increasingly externalize migration as a form of “remote control” to reduce migration across their own borders (Dastyari and Hirsch 2019; FitzGerald 2019; Menjívar 2014; Zolberg 2003). For controlling refugee flows, state externalization of migration and security manifests through asylum policies, border politics, non-entrée policies, and soft power, such as soft law bilateral and multilateral cooperative agreements (Dastyari and Hirsch 2019; FitzGerald 2019). For example, Frontex, the EU’s border agency, and its “Euro-Moat” strategy buffers European states from refugee arrivals through a combination of preventing departures from North Africa and Türkiye to shifting border enforcement beyond EU territory. These efforts force travelers away from sea borders through pushbacks, intercept migrants at sea, prosecute individuals who rescue migrants in distress, and impose sanctions on countries (FitzGerald 2019). Such remote control tactics are often motivated by racism and xenophobia in states in the Global North, and they result in severe violations of the human rights of refugees, changing migration routes, and increases in risks along the way (Dastyari and Hirsch 2019). Conversely, under the new grand compromise, states in the Global South also opted to frame themselves as “buffer states” to increase their leverage in the receipt of resilience aid (Arar 2017).

In this paper, we examine these global changes in refugee flows using two hypotheses related to (1) the structural position of intermediary countries and (2) how refugee flows are shaped by international aid through monetary donations. Our analyses are organized according to these two hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1.

States with higher geopolitical centrality in refugee networks, measured by their frequency of observed refugee inflows and outflows, are likely to continue serving as intermediary states by receiving and sending refugees who may have otherwise not passed through an intermediate host country.

We expect that these intermediary transit countries display wide variation and can also serve as buffers if there are changes in the nature of their routing role. If intermediary states facilitate less refugee movement toward final destination countries and are observed to be less frequent intermediaries due to limited outflows, this may provide evidence that they are acting as buffer states. Countries widely recognized as buffer states, such as Türkiye and Jordan, may register different frequencies as intermediaries precisely because they successfully limit onward movement.

Due to poor governance, insecurity, liminal legal protections, and limited rights in host countries, refugees are taking greater risks in their migration journeys. They are traveling greater distances across multiple transit countries because there are very few pathways to legally travel to a safe country and apply for asylum. For refugees and asylum seekers who successfully arrive to a safe intermediary country, temporary legal protections are increasingly common tools used by states to regulate migration and temporary residence (Cook-Martín 2019; Laube 2019). With the allocation of temporary protection status, countries along key migration routes increasingly become “intermediary” countries situated in an “us versus them” binary between the Global North and South (Oelgemöller 2011).

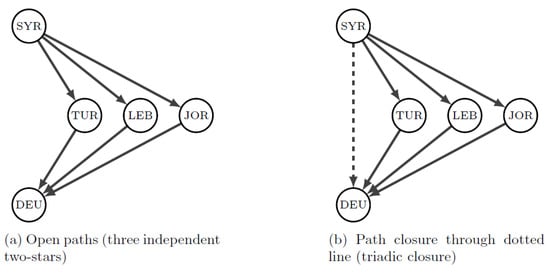

Figure 1 visualizes this hypothesis through network analysis, where the nodes of Turkïye (TUR), Lebanon (LEB), and Jordan (JOR) are intermediary countries between Syria (SYR) and Germany (DEU). Border externalization would mean that the direct connection between Syria and Germany is suppressed, as shown in panel (a). Otherwise, intermediary transit routes may operate in parallel, increasing in the propensity of Syria forming a direct tie with Germany. In network terms, the growing significance of states that are structurally positioned as intermediary countries may decrease the possible direct flows to “third” destinations. This would decrease the tendency for triadic closure, in which the possible triangles formed by two-path indirect transit routes are closed directly, as shown in panel (b).

Figure 1.

Role of intermediary countries in shaping flows from “first” to “third” countries.

Hypothesis 2.

Intermediary states strategically occupy brokerage positions by securing monetary aid that reduces refugee outflows.

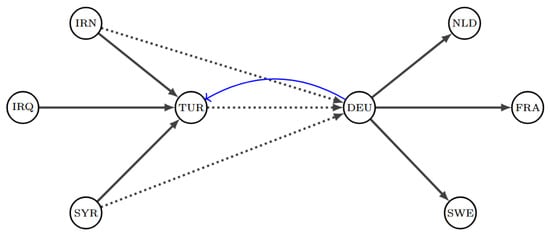

Externalized refugee governance can incentivize containment in intermediary countries and discourage permanent integration, thereby suppressing outflows and reinforcing their structural importance as brokers. “Transit countries” have been shown to support a country’s intermediary status and indifference towards permanent resettlement of the migrants in the country, and by doing so, secure continued support from Global North donor countries for these groups (Norman 2019). In these actions and decisions of state power, negligence for resettlement among both intermediary countries and large-donor countries are purposeful and strategic, meaning that the Global North’s “fortress” against refugees works indirectly through international aid to develop and sustain intermediary capacities of transit countries. We visualize the effect of donations on refugee network flows using a theoretical diagram presented in Figure 2. While Türkiye may initially serve as an important intermediary country that continues to send refugee outflows, monetary aid to Türkiye, as indicated by the blue line, may serve to suppress or decrease the likelihood of further outflows. While our first hypothesis examines the structure and role of intermediary countries, the second focuses on how monetary aid conditions their routing and transit functions in sending and receiving refugees.

Figure 2.

Role of monetary donations in shaping transit routes through intermediary countries.

4. Data and Methods

Network analyses have shown how migration flows have evolved globally across time through the study of international mobility (Hou and Du 2022; Huang and Butts 2023; Leal 2021; Leal and Harder 2022). Network models examine the directionality of ties within different possibilities of triadic configurations, which parallels our approach to how ties emerge across different configurations of flows between “first,” “second,” and “third” countries. A tie is represented in the analysis as a refugee flow from one country to another. A developed and burgeoning literature focuses on how transitivity—the likelihood that nodes cluster and form triangles—and cyclicality—the manner in which these triangles form a complete “cycle” or full loop (i → j, j → k, and k → i)—are important indicators for hierarchy (Huang and Butts 2023, p. 1052; Leal 2021, p. 1083). From a network approach, the i → k or SYR → DEU tie in Figure 1 remains contingent on both network constraints and the role of intermediary countries, which are themselves shaped by international aid sent and received by each country.

Refugee Flows 1990–2015. We examine the development of the refugee network structure from 1990 to 2015 using estimates by Schellerer (2023) calculated across five 5-year time panels. Our unit of analysis is states as the nodes of the network, and ties are refugee flows between states. Ties are operationalized by tracking flows from the top ten refugee origin countries to account for major refugee origins across each panel. Schellerer’s estimates for refugee flows are calculated using established demographic accounting methods and include information on place of birth, origin, and destination, resulting in global refugee flow data that are comparable across time and region (Schellerer 2023). We select place of birth to focus on those born in countries that were in the top ten refugee origins in each 5-year panel from 1990 to 2015, tracking refugees born in 27 unique countries, as shown in Table 1. Tracking those born in these high-origin countries is valuable because it allows for ties to be indicated based on movement of the same highly vulnerable communities over time across their journeys and helps to avoid capturing flows among nationalities and places of birth, such as in Western Europe, that are not the focus of the analysis for those traversing between the Global North and South.

Table 1.

Top ten largest estimated five-year refugee transition outflows.

Flows are binarized to capture the most important corridors in each panel in the top percentile of flows, ranging from a flow of at least 5470 refugees in 1990–1995 to at least 3313 in 2010–2015. This dichotomization by top percentile accounts for over 95% of the numeric volume of refugee movements for each panel. Dual selection by top percentile and by birth in the top ten origin countries is explicitly employed to capture the top state actors between which tie formation occurred at least once from 1990 to 2015 (see Table S1). The boundaries of the network contain 199 potential countries through which refugees theoretically could traverse, although most remain isolates, since only 90 of these countries had at least one flow connecting it to another country.1 Analytically, these flows highlight changes in the geography of largest flows, account for variation in total refugee numbers over time by tracking the top percentile, track the same movements from high-origin places of birth across distinct steps, and simplify computations for longitudinal network analysis on binary flows.

Donations. Reflecting the increase in donations to the UNHCR following 2015 (Arar 2017), we capture monetary aid given and received by countries between 2017 and 2021 using UNHCR donor data scraped at the end of 2022. We include country donor data until 2021. As UNHCR’s calculations and estimates can change, especially at the beginning of crises, we restricted our analysis to 2021 to ensure finalized donor data.2 UNHCR donor data are organized according to situations and emergencies, such as the “Democratic Republic of the Congo Situation,” with a situation implicating multiple countries; for example Burundi, Uganda, and Rwanda. Therefore, we divide donations to a situation evenly across all state actors affected (see Table S3 for mapping).3 Since donations can be sent by regional and international organizations accounting for the total amount a country received each year, donor data are operationalized by country as a node or state-level attribute rather than an edge-level covariate between two state actors. The node-level characteristic for amount sent every year is only available for donations associated with a specific country, including private actors.

Refugee Flows 2017–2021. Schellerer’s refugee flow estimates are only available until 2015 and do not overlap with the same time period in which our node-level donor data are collected, so ties and flows from 2017 to 2021 are operationalized using UNHCR’s Refugee Data Finder stock data for refugees, using differences in successive refugee stocks, under UNHCR’s mandate and asylum seekers. Similar to our analytic strategy from 1990 to 2015, we measure a tie through binarization, and a tie is counted if it includes the top decile of refugee flows from 2017 to 2021. This binarization accounts for over 97% of the numeric volume of refugee movements across each year. Secondly, the boundary of this 2017–2021 network is restricted to major crises and situations that align with high levels of financial need identified by UNHCR’s situation categorization. Consequently, we focus geographically on major refugee corridors in Africa, Europe, and West, Central, and South Asia, totaling 128 countries (see Table S2).4

Model. We employ longitudinal network analysis to examine the outcome of refugee ties using temporal exponential random graph modeling (TERGM), which is fundamentally a logit model for the probability that a tie or edge, in our case a flow, connects two nodes, or countries, conditional on network structure, covariates, and the non-independence of ties. TERGM has the ability to specify both within- and between-panel dependencies, with the latter being able to determine “whether a tie is more likely to form if it closes a previously open triangle” (Duxbury 2022, p. 23), represented by Figure 1 in our case.

Network parameters. We test the role of intermediary countries, their potential to serve as buffers, and whether donations shape the role of these intermediary countries by employing network parameters. Intermediary count considers how many times a country appears in the middle of a directed two-path structure (j in the two paths of i → j, j → k) based on the actual observed network each year. This captures the traversing of any “second” country, regardless of whether the country falls on the shortest or most optimal route between two countries. Our measure of centrality differs from betweenness centrality because the latter only focuses on the shortest possible routes connecting two nodes and would not count all intermediary countries. In contrast, our intermediary count measures every empirically observed indirect path, irrespective of its length. For example, if refugees travelled the path Syria → Jordan → Greece → Germany, and there is a shorter possible route, Syria → Greece → Germany, then betweenness centrality would discount Jordan’s intermediary role.5 Given the range of intermediary countries, countries may have lower intermediary scores if they are successfully containing refugee populations and limiting onward movement. While high intermediary scores suggest active transit and brokerage, low scores may signal containment and enforced stasis. DGWESP, or directed geometrically weighted edgewise shared partners, measures whether countries that share migration connections also tend to form additional migration ties as part of a closed triangle, visualized in Figure 1b. Edges function as an “intercept” term and measure the baseline log-odds of a tie, mutual controls for bidirectional flows by accounting for whether ties appear as part of a reciprocal relationship, and memory accounts for temporal dependence regarding what kind of new ties are likely to emerge given the network’s past structure.

Geopolitical and migration parameters. Our primary geopolitical measures are the amount of donations received and donations sent as country-level covariates. In addition, we account for cultural, geographic, economic, and political variables from the Gravity database (Conte et al. 2023) that are expected to shape movement and propensities for refugee sending and receiving across Global North and Global South countries. We account for the difference in polity score or political stability between two countries along a spectrum, with negative values suggesting autocracy and positive values suggesting democracy (Marshall et al. 2016), whether there is a trade agreement between two countries, specifically a free trade agreement (FTA) or economic integration agreement (EITA) (Conte et al. 2023, p. 20), and proximity through shared presence in a geographical subregion, as classified by the United Nations geoscheme. As many refugees flee authoritarian regimes towards buffer states that leverage trade agreements and geopolitical negotiations, such as through the Jordan Compact, these measures aim to capture the dynamics of the new grand compromise (Arar 2017). To capture world systems and Global North and South dynamics, we also include whether European Union (EU) members are more likely to receive refugee flows. We also consider Human Development Index (HDI) scores from 1990–2022 by the United Nations Development Programme,6 whether countries share a common language, and whether there are also major outward or return migration flows (Abel and Cohen 2019) as an edge covariate that is binarized if the flow is in the top percentile of outward or return migration flows during that panel.

5. Results

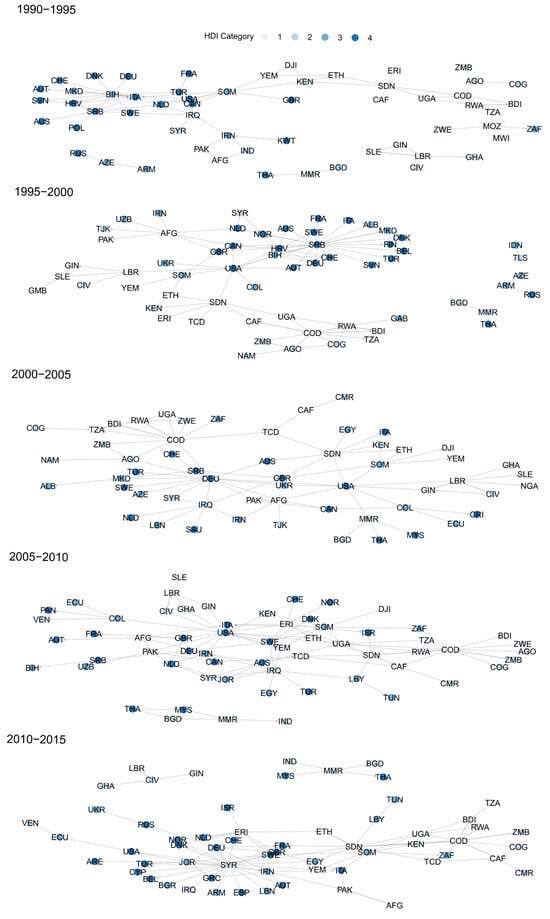

Figure 3 provides a visualization of our five-year panel networks, excluding isolates. The visualization of network structure shows directed refugee flows between countries with each country’s HDI score category, ranging from “Low” in the lightest blue to “Very High” in the darkest blue. We highlight the polarization of low and high HDI counties, with each tending to cluster on one side of the network visualization. This descriptively supports hypothesized North/South divisions and how these divisions are bridged by key transit countries and nodes that serve as bridges. Notably, the nodes are centered around countries that are primary receivers and primary senders of refugee flows.

Figure 3.

Visualization of refugee flows from 1990 to 2015 (5-year panels).

General network-wide descriptive statistics are presented in Table 2. Noticeably, the very low network density indicates the presence of many isolates that are unconnected. Next, the measure of how correlated each refugee network structure is with an idealized core–periphery structure (Borgatti and Everett 2000), calculated using node degrees for which top-degree nodes consist of the core and with core–core ties marked as 1 and periphery ties as 0. There is evidence of increasing correlation between idealized core–periphery structures and observed refugee networks from 1990 to 2015. The global clustering coefficient is a measure of subgroup formation and demonstrates that flows have tendencies to form hubs, and local triadic closure increased from 1990 to 1995 before plummeting in 2005, likely marked by breakdown of local clusters around the same time of the Darfur and Iraq crises that funneled Sudanese and Iraqi refugees. The emergence of regional refugee corridors, especially following the invasion of Afghanistan, represents shifts primarily from Sub-Saharan Africa to Western and Central Asia, suggesting that triads increased again in 2010 as routes re-stabilized.

Table 2.

Descriptive metrics for network structure over time.

The mean geodesic distance indicates that the average shortest path length between any two random countries increased by approximately 90% from 2000 to 2005. This suggests that there were a greater number of steps in the network taken by an average flow to represent longer-distance and more complex, multi-country transit routes, especially starting in 2005 with the prominence of outflows from Western Asia; this is also supported by a spike in betweenness centrality in 2005. Mean constraint measures whether nodes act more as brokers in the network, with more opportunities for bridging, or are more constrained, with fewer structural holes. Constraint is consistently high to indicate states are interconnected across refugee flows. However, the drop in 2005 indicates that more “holes” appear in the network and there are more brokerage opportunities for intermediary countries to bridge between different areas of the global network. These global statistics indicate that the first decade of 2000 was an important juncture in shaping network structure.

5.1. Shared Responsibility and Intermediary Bridges

We build on our descriptive statistics using TERGM to statistically test our first hypothesis regarding the role of intermediary countries in sending and receiving flows while accounting for geographic, cultural, and development measures across the Global North and South. Table 3 presents the results from our first model using average marginal effects (AMEs) using the ergMargins package to account for scaling in binary outcomes (Long and Mustillo 2018; Duxbury 2023). This allows us to examine changes in percentage points. We first examine the baseline of tie probability using the average predicted tie probability calculated from observed change statistics for all country pairs by taking the mean of edge probabilities. There is a very low (0.28%) chance that a randomly chosen pair of countries will have a refugee flow, given that the networks are highly sparse, with 199 countries constituting the boundaries of the network, meaning there are many isolates, and most country pairs do not have refugee ties in any given year.

Table 3.

TERGM results using Schellerer’s 5-year Refugee Flow Estimates, 1990–2015.

There is support for our descriptive statistics and visualization regarding Global North and South dynamics, as EU members are significantly more likely to receive refugee flows, by 7.7 percentage points, on average. The positive finding of difference in regime type also suggests that refugees flow towards developed and more democratic countries in the Global North, aligning with major migration flows. However, we note that regime differences using polity scores do not necessarily mean all refugee flows are going to democratic countries, as they may be going to countries deemed as less authoritative. This is also supported by the finding that flows to the same subregion are more likely than cross-regional flows by 7.2 percentage points, indicating that many refugees go towards neighboring countries. The dual finding that EU countries and neighboring countries outside the EU both play a role in shaping the likelihood of refugee flows suggests a dual responsibility shared by both EU-receiver countries and neighboring countries outside of the EU.

Our intermediary count and DGWESP terms indicate that intermediary countries play a significant role in facilitating refugee flows as transits. The more times a country previously appears in the middle of a two-path structure, the more likely it will send a refugee flow to another country. A standard deviation increase in a country’s intermediary count raises its outflow probability by approximately 1 percentage point and its inflow by 0.5 percentage points. A standard deviation decrease would imply that the outflow probability is lowered by the same amount. Substantively, these effect sizes are small compared to the other variables but are still meaningful given that the baseline average predicted tie probability is low in a highly spare network, suggesting that intermediary countries continue playing an important transit role in both sending and receiving flows.

These flows continue to be formed as part of closed triangles in which refugees can go directly from the first to the third country. The DGWESP term demonstrates that intermediary countries still tend to form as part of closed triangles within a 5-year time period. The positive and statistically significant term is one of the largest structural effects in the model and indicates a strong tendency towards transitivity, where ties are more likely to form between countries that share common partners, consistent with triadic closure. The presence of intermediary countries does not suppress large-scale flows that go directly from refugee origin countries to “final” destination countries, and intermediary pathways form as part of transitive structures in which there is triadic closure over time. This statistically confirms the central role of major receiving countries that have direct ties from origin countries, as visualized in Figure 3. In short, while we find clear support for the role of intermediary countries, they are also likely to appear along direct pathways from first to third, as refugee crises are likely to create both direct and indirect paths. We find support for the hypothesis that geopolitical centrality, expressed through intermediary positioning in the network, is an important factor of refugee flows. However, we do not find direct support that these countries necessarily act as “buffers” by discouraging direct ties. To further investigate this, we incorporate donor data in subsequent models to examine how international aid conditions the role of intermediary countries in shaping onward movement.

5.2. Diminishing Returns of Donations on Outflows from Key Intermediaries

Table 4 displays results using UNHCR stock data for refugees and asylum-seekers between 2017 and 2021 stemming from UNHCR’s priority situations. A tie is present if it exists in the top decile of flows within Africa, Europe, and Central, West, and South Asia. This threshold is used to select the most significant corridors and to geographically match donor data from major international situations covering the same regions, for which publicly available records begin in the same time period (earlier disaggregated donor data is not publicly available). Model 2 includes the same key covariates from Table 3, Model 1 and shows consistent effects with our prior model analyzing flows from 1990 to 2015. The average predicted probability of a flow between any two countries in these is small, with an approximately 2% chance that a randomly chosen pair of countries will have a tie from 2017 to 2021. There are noticeable differences in the 2017–2021 period compared to 1990–2015. The effect of countries frequently acting as intermediaries no longer has a statistically significant effects on receiving flows, but its effect size for sending flows is larger, with a 3.3 percentage point increase for every standard deviation in intermediary count. Furthermore, a tie is more likely to form as part of a reciprocal flow, suggesting that there are mutual refugee flow dynamics, and countries receiving refugees are also sending them.

Table 4.

TERGM estimates for donor and refugee flows from stock data, 2017–2021.

Model 3 includes node-level donor covariates to suggest that donations shape refugee flows. We first note that model fit according to the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) improves, suggesting that donations provide important additional information. Countries that received one standard deviation more in donations in the prior year are more likely to send refugees in the current year by 1.9 percentage points. This highlights refugee transit through routing countries that initially host large populations before they continue elsewhere, representing structurally important nodes that encourage further outflows. Receiving aid, however, has no statistically significant effect on receiving flows, which suggests that aid recipients are themselves sources of major refugee flows because they are classified as priority situations of focus for UNHCR. Between Model 2 and Model 3, the sending effect size for countries acting as intermediaries decreases from 3.3 to 2.5 percentage points when accounting for donations. Mediation analysis shows that the 24% decrease in the total effect of sending a refugee flow as a frequent intermediary country could be attributed to donation variables, but the proportion mediated is not statistically significant (see Table S5).

Model 4 includes an interaction effect between the structural position of intermediary countries and the amount of donations received by that country. While both parameters are individually expected to increase refugee outflows, the interaction effect is statistically significant and negative, despite the model resulting in a worse AIC. The probability of sending a refugee outflow as a major aid recipient is dampened if a country is also a major intermediary country. The negative interaction term tempers the combined effect. At an average intermediary count, a one standard deviation increase in donations raises the tie probability to 3.2 percentage points. However, for countries with intermediary counts, one standard deviation above the mean, the same increase in donations is associated with only a 2.1 percentage point increase (0.032–0.011). This represents a 34.4% relative decrease in the effect of donations, suggesting that aid becomes less effective at increasing onward refugee movement as a country’s intermediary role intensifies. In short, donation aid has a diminishing marginal effect on increasing refugee outflows from countries already established as frequent intermediaries. Together, these results show that geographic affinities and structural network patterns strongly shape global refugee pathways, while aid interacts modestly but significantly to stabilize these flows through intermediary states.

6. Discussion

Our results highlight the importance of examining the role of intermediary countries in shaping refugee flows and broader global network structures of movement. First, we find that direct ties from the first country to the third country are not suppressed or do not disappear with the presence of intermediary countries, but rather the opposite is supported within the scope of our study. The results indicate no evidence of triadic closure being avoided. On the contrary, the formation of two paths (first → intermediary → third) increases the likelihood of a direct tie (first → third). Our second key finding relates to donations and how they condition the effect of being a high-intermediary country. While intermediary countries are expected to be more likely to send refugee outflows, this effect diminishes as levels of received monetary aid increase. The structural positioning of intermediary countries may thus be changing as stabilized transit hubs through international donations and aid. We discuss the implications of these findings for global refugee management.

We find mixed support for our hypothesis that geopolitically central countries positioned in the network would lead to border externalization by acting as buffers (Hypothesis 1). Intermediary countries continue to be important in sending outflows, and the distance and steps that refugees take appear to increase through diversified routing points in networks that display transitivity. Strong support for the effect of intermediary countries may itself be a sign that buffering dynamics are at play, given that decreases in intermediary scores would imply percentage point decreases in further outflows. However, we address the issue of selection into being an intermediary country to begin with. For example, for countries to have high intermediary counts, they themselves need to also be sending large outflows. Yet, if buffers really are enacted and externalization is fully implemented, then these “intermediary” countries would become “final” destinations in themselves; therefore, these “pure” buffer countries may lead to a right-skewed distribution of our intermediary measurement if they do not send any outflows and are counted as being an intermediary zero times. This would imply an underestimation of buffering effects. For example, prior research on Turkïye as a major intermediate country and its status as a major hub and recipient of refugee inflows does not make it the highest intermediary country in our analysis, because although it may be receiving a large amount of flow, it is not sending as many outflows as other high-intermediary-status countries, such as Ethiopia, Sudan, or Iraq (Table S4). Similarly, Jordan does not have a high intermediary count because it is not sending large outflows that would constitute the top decile of flows with the boundaries of the network, despite being a major refugee hosting country occupying a structurally important bridging position (Arar 2017). While our analysis highlights the intermediary role of countries as routing points, it is nonetheless limited if buffer states are truly acting as complete buffers.

We find partial support that intermediary states strategically occupy brokerage positions by securing monetary aid that reduces refugee outflows (Hypothesis 2). Findings suggest that large increases in donations can moderate the tendency of intermediary countries to continue sending large refugee ties to farther destinations. While we find continued support that refugee flows are shaped by transitivity and routing, given the positive tendence for triadic closure, our statistically significant negative interaction term between the amount of donations a country receives and being a high intermediary country suggests that aid may enable intermediary states to retain or contain refugee populations, even if they do continue to encourage further outflows. Despite the new grand compromise and increase in donations to the UNHCR after 2015 (Arar 2017), refugee outflows persist within the scope of our analysis. Brokerage can be a double-edged sword.

There are two possible interpretations for a country that is frequently an intermediary while also receiving large amounts of aid. Large amounts of aid may be encouraging more containment by allowing a country to develop its hosting capacities despite the country itself being a source of ongoing refugee flows. In other words, intermediary countries may receive aid precisely to act as latent containment zones; this would support their role as buffers between Global South and Global North countries. This interpretation would suggest that being funded by donations and positioned structurally as an important transit may serve to limit refugee onward movement, as prior theories suggest (Hamlin 2021; Norman 2021). Alternatively, the positive effect of either donations or being a high intermediary country may diminish when both are high due to resource strain, policy pressure, or intentional hosting or trade agreements, such as the EU–Türkiye deal or the Jordan Compact. In other words, large inflows of aid and transit traffic increases hosting capability and may reduce incentives for the country to continue sending refugees.

Viewed from the externalization of borders hypothesis, humanitarian aid that is disproportionately channeled to intermediary states with the goal of stabilizing refugee flows may eventually act as a containment mechanism and reduce onward movement. Viewed from a development perspective, these structurally important countries in refugee networks may be developing a greater capacity to become destinations themselves or may simply leverage development aid for the benefit of its own citizens (Arar 2017). Based on the findings, increases in donations and resilience funding for states in the Global South most likely constrain refugee autonomy for onward movement, with refugees continuing to experience insecurity, liminal status, and limited integration (UNHCR 2024; Müller 2024). In this way, while states in the Global South benefit from the new grand compromise of refugee protections, the rights, security, and autonomy of refugees remain constrained.

The results underscore that geopolitical centrality within refugee networks may enable strategic agency among intermediary countries, despite sometimes being at the center of crises with large sending and receiving refugee flows. This aligns with literature that highlights refugee hosting as a source of diplomatic leverage and geopolitical influence (Arar 2017; Norman 2021; Hamlin 2021). This structural position is important even after accounting for a variety of geopolitical influences, including trade and economic agreements, differences in political regimes using polity scores, human development index differences, common language, existing migration flows, and geographic proximity. These findings suggest that intermediary countries actively manage their structural role as routing points through negotiations, but the geopolitical influence of intermediary countries is mixed. While their agency in refugee governance may emerge from their central network position and strategic interactions with international donors, many high intermediary countries are in vulnerable positions because they are both the source and host for refugees fleeing geopolitical crises and instability. Thus, while countries like Jordan and Türkiye can successfully leverage their positions, other intermediate countries, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, or Iraq, may remain highly vulnerable. Thus, while geopolitical centrality may enhance leverage, this structural characteristic of intermediate centrality may underscore precarity as well.

While this study is innovative in its use of UNHCR donor data to analyze the interplay between donations and refugee flows, we note two major limitations stemming from the data and subsequent analysis. First, publicly available donor data reporting is constantly changing. While we were initially able to access country-to-country donor data, the UNHCR later removed this data from its website, requiring us to rely on data by “situation.” This grouping makes it more difficult to directly track and accurately operationalize donations using flows at the edge-level, which is why we only examined aid as a node attribute. More transparent and granular donor data is needed. Relatedly, UNHCR donor data are currently only available since 2017 and limit our ability to test hypotheses about the impact of donations over time. To test theories of externalization of refugee flows and a comparison of UNHCR donations under the grand compromise and new grand compromise eras would require donor data from the 1980s (FitzGerald 2019) or more granular data (e.g., monthly, quarterly) of refugee stock to more accurately capture flows. This research could benefit from more detailed aid categorization according to the UNHCR’s outcomes and impact or enabling areas, but these data are not available at the country or situation level. However, an aggregated donation measure identified based on major situations still captures a meaningful signal about aid, since strategic financial support provided to key intermediary states continues to be part of the global refugee governance regime, whether used as humanitarian relief or broader capacity-building.

A second limitation relates to the selection of countries as major transit hubs in our analysis. Intermediary status using our measure of the number of times a country falls in the middle of two-paths may be capturing major sending countries that themselves receive flows from neighboring countries, such as in the case of the Democratic Republic of Congo, or countries like Türkiye, which could already be a “final” destination for many. In other words, our measure of intermediary status may be capturing transits that function more as “first” countries, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, or “third” countries, such as Türkiye, rather than our hypothesized “second” country tests. In both cases, we would be underestimating funneling effects and buffers. Relatedly, due to this selection, it is likely that donations are allocated precisely to countries already identified as major sending countries, and thus aid donations would respond to existing outflow pressures rather than to countries that are targeted for containment. This may explain why we fail to find negative triadic closure effects and why receiving substantial aid does not directly suppress flows. Moreover, Türkiye itself may not be the country of origin reported in UNHCR data even if refugees are temporarily there, and further data are needed on place of birth for those making the journey from origin to asylum to resettlement so that aggregate flows can be more accurately examined over time.

Our findings underscore the interconnectedness of refugee flows, suggesting that refugee movements are not isolated national phenomena but are part of a broader global network. This highlights the critical importance of understanding the existence of a global division of responsibility sharing. We introduce this concept to describe the distribution of obligations and resources among nations in response to refugee crises. Despite the increased leverage of host countries in the Global South following the 2015 refugee flows to Europe, the demonstrated persistence of intermediary countries as crucial hubs in refugee transit networks, coupled with the effects of international donations, points toward persistent divided functions between Global North and Global South countries, where refugee responsibilities are accompanied by unequal burdens and unequal refugee protections. Relational analysis of countries and their actions illustrate that efforts to provide temporary protections, permanent resettlement, deportation, or containment are not isolated decisions but implicate an entire network of actors. Rather than solely reinforcing border externalization or containment strategies, the global division of responsibility sharing involves acknowledging and addressing the roles and pressures experienced by structurally important transit countries together with sending and receiving countries.

We contextualize the concept of a global division of responsibility sharing considering the limitations of our analysis. Countries identified as intermediaries in our study may themselves be significant sources or destinations of refugee movements, thus complicating the definition and practical implementation of responsibility-sharing mechanisms. Moreover, the nuanced interaction between aid and transit dynamics indicates that international donations have complex and sometimes contradictory effects. The provision of aid to structurally critical countries may stabilize populations in the short term but may also inadvertently reinforce these countries’ positions as perpetual buffer zones or containment areas. Therefore, while the division of global responsibility sharing offers a promising conceptual framework for addressing refugee protection on a systemic scale, policymakers and scholars must remain attentive to its complexities and potential unintended consequences.

7. Conclusions

Our study highlights the theoretical and empirical development of contemporary refugee systems and how network constraints are interpreted and operationalized on a macro-scale, when “local” bridges become global. Analyzing data from both Schellerer (2023) and publicly available UNHCR refugee stock and donor data, we were able to demonstrate robustness across different data sets. Using these data, we examined major and important contemporary refugee flows. We found support that refugee flows are towards Global North and more developed countries, as well as towards countries neighboring those from which refugees originate. The large effect size shows that both EU countries and countries neighboring those with large outflows play a role in shaping the likelihood of refugee flows. As the first study to empirically examine the impacts of donor data on refugee flows, we find that countries receiving more aid are correlated with more refugee outflows. However, receiving aid has no statistically significant effect on receiving flows, which suggests that aid recipients are themselves sources of major refugee flows because they are classified as priority situations of focus for UNHCR.

Based on these findings, we introduce the conceptual framework of a global division of responsibility sharing to describe how functions of Global North and Global South countries continue to constitute unequal burdens and unequal refugee protections. While counterfactual data about flows in the absence of aid is not currently available, the global division of responsibility sharing suggests that donations alter refugee flows, in line with existing theories of externalization and despite increased leverage of Global South states post-2015. Current U.S. development policy shifts in 2025, including towards refugees, may provide a natural experiment to build on this study when donation and flow data become available.

Finally, our findings indirectly highlight how the existing global division of responsibility sharing is consequential for refugees’ access to resources and social and human rights. Although refugee flows are towards Global North and more developed countries, as well as neighboring countries, the protections that refugees receive in these countries are increasingly temporary, insecure, and limited, minimizing differences between protections in intermediary and final destination countries. Furthermore, although UNHCR humanitarian support aims to extend resources for refugees, our findings that flows persist even amidst high donations raise questions about the extent to which UNHCR humanitarian support sufficiently realizes refugees’ humanization, access to resources, and fulfillment of social and human rights. As we acknowledge the existence of a global division of responsibility sharing, policymakers and migration experts must continue to interrogate shortcomings of the existing structure of responsibility sharing and advocate for better protections that prioritize the well-being of refugees.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/socsci14070434/s1, Table S1: Countries Analyzed from 1990–2015; Table S2: Country ISO3 Codes with UN Subregions; Table S3: Top 10 Countries by Intermediary Count by Year; Table S4: UNHCR Situation to Country Mapping; Table S5: Mediation of Donor Variables on Direct Effect of Intermediary Count from Table 4, Model 2 and Model 3.

Author Contributions

The authors contributed equally. Conceptualization, A.H.V. and M.S.D.-S.; methodology, A.H.V. and M.S.D.-S.; software, validation, A.H.V. and M.S.D.-S.; formal analysis, A.H.V. and M.S.D.-S.; investigation, A.H.V. and M.S.D.-S.; resources, A.H.V. and M.S.D.-S.; data curation, A.H.V. and M.S.D.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H.V. and M.S.D.-S.; writing—review and editing, A.H.V. and M.S.D.-S.; visualization, A.H.V.; supervision, A.H.V. and M.S.D.-S.; project administration, A.H.V. and M.S.D.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data and code supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This includes all 200 countries in Abel and Cohen’s (2019) migration estimates, except for Channel Islands due to missing data across the different data sources employed. |

| 2 | Notably, this excludes the very significant onset of refugee flows due to the Russian–Ukraine conflict. However, for reasons of inconsistent data at the beginning of crises, we restrict our analysis. We do not exclude Ukraine from the analysis but rather restrict our time constraint due to these data limitations. Our core claims of our paper, which are framed around Global North and Global South distinctions and the top refugee corridors in Afro-Eurasia meant that we were particularly interested in refugee crises from before 2021. Donor data were collected from UNHCR donor profiles (https://www.unhcr.org/about-unhcr/planning-funding-and-results/donors, accessed on 12 April 2024), which are regularly updated every two weeks. We also note that data scraped earlier included donations from a country to specific countries; however, country-to-country data were no longer available in 2022 when we obtained the data used here in analysis. |

| 3 | For more information on UNHCR situations and involved countries, see: https://reporting.unhcr.org/operational/situations, accessed on 12 April 2024. |

| 4 | We focus on the top decile rather than percentile because these geographic areas and routes host the largest flows, and the top decile would create a restrictively high threshold for binarization. |

| 5 | Our measure, in contrast, focuses on this intermediary role and is motivated by similar terms, such as the mixed two-star endogenous network term, which focuses on j in the i → j → k relationship but is not a node-level term for outgoing and incoming specificity, and the notion of waypoint flows (Huang and Butts 2023). |

| 6 | https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/documentation-and-downloads, accesssed on 12 April 2024. |

References

- Abdelaaty, Lamis Elmy. 2021. Discrimination and Delegation: Explaining State Responses to Refugees. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Abel, Guy J., and Joel E. Cohen. 2019. Bilateral international migration flow estimates for 200 countries. Scientific Data 6: 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arar, Rawan. 2017. The new grand compromise: How Syrian refugees changed the stakes in the global refugee assistance regime. Middle East Law and Governance 9: 298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, Stephen P., and Martin G. Everett. 2000. Models of core/periphery structures. Social Networks 21: 375–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, Ronald S. 2004. Structural holes and good ideas. American Journal of Sociology 110: 349–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Elizabeth H. 2006. Urban refugees in Nairobi: Problems of protection, mechanisms of survival, and possibilities for integration. Journal of Refugee Studies 19: 396–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, Maddalena, Pierre Cotterlaz, and Thierry Mayer. 2023. The CEPII Gravity Database. CEPII Working Paper. Available online: https://www.cepii.fr/DATA_DOWNLOAD/gravity/doc/Gravity_documentation.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Cook-Martín, David. 2019. Temp nations? A research agenda on migration, temporariness, and membership. American Behavioral Scientist 63: 1389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook-Martín, David, and David Scott FitzGerald. 2019. How their laws affect our laws: Mechanisms of immigration policy diffusion in the Americas, 1790–2010. Law & Society Review 53: 41–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuéller, Mariano-Florentino. 2006. Refugee security and the organizational logic of legal mandates. Georgetown Journal of International Law Standford Public Law Working Paper 37: 1–102. [Google Scholar]

- Dastyari, Azadeh, and Asher Hirsch. 2019. The ring of steel: Extraterritorial migration controls in Indonesia and Libya and the complicity of Australia and Italy. Human Rights Law Review 19: 435–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Genova, Nicholas, Glenda Garelli, and Martina Tazzioli. 2018. Autonomy of asylum? South Atlantic Quarterly 117: 239–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devictor, Xavier, Quy-Toan Do, and Andrei A. Levchenko. 2021. The globalization of refugee flows. Journal of Development Economics 150: 102605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxbury, Scott W. 2022. Longitudinal Network Models. SAGE Publications. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury, Scott W. 2023. The problem of scaling in exponential random graph models. Sociological Methods & Research 52: 764–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FitzGerald, David Scott. 2019. Refuge Beyond Reach: How Rich Democracies Repel Asylum Seekers. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- FitzGerald, David Scott, and David Cook-Martin. 2014. Culling the Masses: The Democratic Origins of Racist Immigration Policy in the Americas. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Available online: http://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.4159/harvard.9780674369665/html (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Garavini, Giuliano. 2007. The colonies strike back: The impact of the Third World on Western Europe, 1968–1975. Contemporary European History 16: 299–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, Mark. 1985. Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology 91: 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlin, Rebecca. 2021. Crossing: How We Label and React to People on the Move. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Lisa. 2000. Deterrence measures and the preservation of asylum in the United Kingdom and United States. Journal of Refugee Studies 13: 184–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooghe, Marc, Ann Trappers, Bart Meuleman, and Tim Reeskens. 2008. Migration to European countries: A structural explanation of patterns, 1980–2004. International Migration Review 42: 476–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooks, Gregory. 2020. War, states, and political sociology: Contributions and challenges. In The New Handbook of Political Sociology, 1st ed. Edited by Thomas Janoski, Cedric de Leon, Joya Misra and Isaac William Martin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 924–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Chunguang, and Debin Du. 2022. The changing patterns of international student mobility: A network perspective. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48: 248–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Peng, and Carter T. Butts. 2023. Rooted America: Immobility and segregation of the intercounty migration network. American Sociological Review 88: 1031–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laube, Lena. 2019. The relational dimension of externalizing border control: Selective visa policies in migration and border diplomacy. Comparative Migration Studies 7: 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, Diego F. 2021. Network inequalities and international migration in the Americas. American Journal of Sociology 126: 1067–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, Diego F., and Nicolas L. Harder. 2022. Migration networks and the intensity of global migration flows, 1990–2015. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loescher, Gil. 2001. The UNHCR and World Politics: A Perilous Path. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Scott, and Sarah A. Mustillo. 2018. Using predictions and marginal effects to compare groups in regression models for binary outcomes. Sociological Methods & Research 50: 1284–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, Monty G., Ted Robert Gurr, and Keith Jaggers. 2016. Polity IV Project Dataset User’s Manual. Polity IV Project. Available online: https://www.systemicpeace.org/polity/polity4x.htm (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Menjívar, Cecilia. 2014. Immigration law beyond borders: Externalizing and internalizing border controls in an era of securitization. Annual Review of Law and Social Science 10: 353–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, Tanja R. 2024. Liminal legality and the construction of belonging: Aspirations of Eritrean and Ethiopian migrants in Khartoum. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 51: 179–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumayer, Eric. 2004. Asylum destination choice: What makes some West European countries more attractive than others? European Union Politics 5: 155–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, Kelsey P. 2019. Inclusion, Exclusion or Indifference? Redefining Migrant and Refugee Host State Engagement Options in Mediterranean ‘Transit’ Countries. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45: 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, Kelsey P. 2021. Reluctant Reception: Refugees, Migration, and Governance in the Middle East and North Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oelgemöller, Christina. 2011. ‘Transit’ and ‘suspension’: Migration management or the metamorphosis of asylum-seekers into ‘illegal’ immigrants. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37: 407–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özden, Çağlar, Christopher R. Parsons, Maurice Schiff, and Terrie L. Walmsley. 2011. Where on earth is everybody? The evolution of global bilateral migration 1960–2000. The World Bank Economic Review 25: 12–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Ian Sanjay. 2021. We’re Here Because You Were There: Immigration and the End of Empire. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, Anju Mary. 2011. Stepwise international migration: A multistage migration pattern for the aspiring migrant. American Journal of Sociology 116: 1842–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, Alejandro, and John Walton. 1981. Labor, Class, and the International System. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schellerer, Stefan. 2023. Estimating global bilateral refugee migration flows from 1990 to 2015. International Migration Review 59: 896–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, Jason. 2018. Why here? Factors influencing Palestinian refugees from Syria in choosing Germany or Sweden as asylum destinations. Comparative Migration Studies 6: 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNHCR. 2024. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2023. UNHCR: The UN Refugee Agency. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/global-trends-report-2023 (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Wallerstein, Immanuel Maurice. 2004. World-Systems Analysis: An Introduction. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, Jake. 2023. Standardizing refuge: Pipelines and pathways in the U.S. refugee resettlement program. American Sociological Review 88: 681–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Suzie S., and Shinwoo Choi. 2021. Examining refugee integration: Perspective of community members. Journal of Refugee Studies 34: 354–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolberg, Aristide R. 2003. The archaeology of ‘remote control’. In Migration control in the North Atlantic World: The Evolution of State Practices in Europe and the United States from the French Revolution to the Inter-War Period. Edited by Andreas Fahrmeir, Olivier Faron and Patrick Weil. New York: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).