1. Introduction

The present article has sought to identify the main issues of interest that have arisen on the web in relation to the new education law, as well as to analyze the socio-educational repercussions that it has generated, establishing relationships between the different educational events and elements involved. Education is considered by

Montero Caro (

2021) to be the cornerstone of any consistent democratic scaffolding, and reforms are one of the main avenues for the resilience of the education system (

Global Partnership for Education 2022).

Whilst the politicization of education is to be avoided (

Simón-Yarza 2021), the establishment of a quality education system is a priority for any contemporary democratic system. However, the qualification of this adjective can be interpreted in different ways depending on the society, country, or even the political ideology of the government responsible for managing educational regulations in a specific time and territory (

Eden et al. 2023;

Montero Caro 2021;

Witenstein and Abdallah 2022), especially given that we are also in a period of particularly virulent educational debate (

Luengo Horcano et al. 2021). This has already been pointed out by

UNESCO (

2025), indicating that all reforms must be adapted to the political, economic and cultural reality of the countries, however, issues such as inclusion, equity or gender equality must be prioritised in all of them.

The LOMLOE has intensified political polarisation in Spain as it was passed without consensus among the main parties, reflecting the persistent absence of a stable educational pact. This law has been perceived by conservative sectors as an ideological imposition, especially in aspects such as the teaching of religion, the treatment of co-official languages, and the competency-based approach to the curriculum. The confrontation has spilled over into the social sphere, with protests from parents’ associations, private schools and regional governments, which has reinforced the division between educational models. Furthermore, the LOMLOE comes on top of a long series of educational reforms promoted by changes of government, which is evidence of a legislative instability that feeds mistrust and confrontation. Instead of building a common framework, the law has deepened the ideological divide, turning education into a political battleground rather than a space for consensus and continuous improvement (

García de Andoin 2021;

Novella-García and Cloquell-Lozano 2021;

Watkins and Donnelly 2020).

The LOMLOE has been established with the objective of modernizing the legal framework to enhance educational and training opportunities for all segments of the population, promote inclusivity in pedagogical practices, elevate student academic performance, and ensure equitable access to quality education (

García-Barrera 2021;

Benítez Gavira and Aguilar Gavira 2024). Following international guidelines such as the

OECD (

2023) or

United Nations (

2023), education systems should integrate different cross-cutting issues that are indispensable in the development of global citizenship. However, the educational counter-reform embodied within this legislation has proven to be a contentious subject (

López-Rupérez 2022) and has been identified as having numerous critical aspects (

Vivancos Comes 2022). The Organic Law 3/2020 of 29 December, which introduces amendments to the Organic Law 2/2006 of 3 May concerning Education (LOMLOE), constitutes a single-article law encompassing ninety-nine sections. Within these sections, precepts of the LOE are subject to partial modification or redrafting. The present article is accompanied by eleven additional provisions, five transitional provisions, one derogatory provision, and six final provisions (

Vogel-Campbell 2025).

This legislative act repeals the Law for the Improvement of Educational Quality (LOMCE) and is based on the Organic Law on Education (LOE), purportedly with the intention of redirecting and adapting it. It is the first Spanish law to incorporate the rights of children and people with disabilities among its fundamental principles (

Arteaga-Alcívar 2024;

García-Barrera 2021;

Marrodán Gironés 2021). Consequently, the legal situation established and developed between 2006 and 2014, when the LOMCE law was implemented, would be recovered, approximately. This legislative act does not constitute a renewal per se; rather, it is a reinstatement accompanied by certain aspects of modernization in the legal framework. This includes promoting the integration of education strategies into national education and development plans, as outlined in the Global Partnership for

Education (

2022). However, ’the LOMLOE, akin to any other educational legislation within a democratic society, formalizes a novel paradigm for achieving the objectives of education. Nevertheless, as is the case with other educational legislation, the drafting and codification of this law give rise to controversial issues (

Esteban Bara and Gil Cantero 2022, p. 13).

The preamble to the LOMLOE commences with the same statements as the LOE regarding the necessity to adapt to contemporary societies in order to enhance the well-being of the entire population (

Ganimian and Murnane 2016;

Polo Sabau 2021;

Trujillo Sáez 2021). This is in line with recommendations such as those of the

United Nations (

2023), which urges governments to adapt educational legislation to different technological and social changes. Furthermore, a concise overview of all pertinent Spanish education legislation is provided, commencing with the Moyano Law of 1857, with a particular focus on the LOE. The LOE was established with the objective of ensuring the provision of quality education and equity for all citizens, aligning with the educational objectives stipulated by the European Union and UNESCO. The conclusion of the LOE development process was marked by the assertion that the methodologies established in 2006 necessitate refinement to ensure their effective implementation.

The LOMLOE stipulates that this update is imperative following the approval of the Organic Law for the Improvement of the Quality of Education (LOMCE) in 2013, which compromised the educational equilibrium established by preceding legislation, constraining the decision-making capacity of the Autonomous Communities, allocating 55% of curricular competences to the Autonomous Communities with a co-official language, and 65% to the remaining communities. The LOMLOE stipulates that 50% of school timetables are to be allocated to the Autonomous Communities with a co-official language, with the remaining 60% allocated to those without.

The legislation under scrutiny here demonstrates a pronounced commitment to the rights of children, the promotion of coeducation, and the assurance of academic success for all students. It is notable for its emphasis on personalized learning, fostering greater empathy towards both the natural and social environment, and the promotion of health within the educational sphere. Furthermore, it seeks to enhance students’ abilities in accordance with the age of technology, while also addressing the gender digital divide. However, the discussion has given rise to a number of socio-educational debates, including those concerning subsidized education and the manner in which it addresses the theological aspect (

Valencia and Luque Guerrero 2021) and the vehicular language (

Martínez-Agut 2021;

Vera Mur 2021).

To summarize, the proposed legislation is intended to enhance the quality of public education by reducing repetition, eliminating Spanish as a vehicular language, and rebalancing the competencies between the government and communities. It is also designed to address the disparities in the distribution of disadvantaged students across public and subsidized educational networks. In relation to this, we see it pertinent to investigate this social mirror in which legislators, if they wish, can look at themselves, and to this end, we ask ourselves; how do the population and organizations respond to the development of the law through social networks? What are the most relevant issues they address? As researchers, this provides us with a new scenario of enquiry and analysis to work on.

2. Materials and Methods

The triple objective of this research is threefold: firstly, to identify the main topics of interest that have emerged in the network around the LOMLOE; secondly, to analyse the educational and social impact of these topics; and thirdly, to establish relationships between the different educational events and the elements involved.

In order to clarify and develop the theory that emerges from the context under investigation, the behaviour of the digital communities on Twitter was explored through grounded theory. Consequently, the trending topic tweets that alluded to educational issues pertaining to the Celaá Law were obtained by means of the data import tool of the ATLAS.ti software. This response is in reference to a data collection technique based on Big Data, utilised for the compilation of all tweets containing the most prevalent hashtags at the time of data collection. The software under discussion is capable of identifying the codes that are to be saturated, and it displays the number of citations that each code has received. This facilitates the application of content saturation for each code and category, as is proposed in the grounded theory. Therefore, although the program is designed for the retrieval of texts, its primary focus is on conceptual work. In this respect, it is important to note that each step of the theoretical coding has been allocated a designated space within the program (

San Martín 2014).

In the present study, the hashtags and users employed as search descriptors were as follows: #StopCelaáLaw; #Celaá; @CelaaIsabel; #EquityEducationFuture; #CelaáLaw; #lomloe; #MorePluralVoices; #WeWillStopCelaaLaw; #RELIsMore. A document was generated for each individual, containing the comments that had been found at that time (see

Table 1). It should be noted that, in the search carried out, all the comments that are currently on the social network are collected, so the data obtained is not limited. In addition, the hashtags were selected using Google tracking tools for trending topics in the social network, to avoid losing any relevance.

Sampling Procedure and Data Collection Methods

Following the application of three exclusion criteria (i.e., the tweet must have been published within the last 30 days, it must not have been reposted, and the content must be analyzable; single images or hashtags alone were not considered), the resulting sample comprised 1536 tweets, collected in two batches during the weeks of 16 and 23 November, when the law was debated and approved in Congress. Finally, those tweets which were deemed to be the most relevant at the time, with regard to the law in question, were selected.

The data presented here was collected using the ATLAS.ti import tool, version 9, and was analysed using the qualitative research methodology grounded theory (

Alarcón Lora et al. 2017). This methodology is considered very appropriate for analysing how people interpret their reality. In order to conduct this form of analysis, it is imperative to consider systematisation in coding (

San Martín 2014). To this end, an initial open coding was conducted to identify the underlying concepts; a subsequent axial coding was then used to determine the relationships that could be found; and finally, a selective coding was employed to analyse the data as a whole.

3. Results

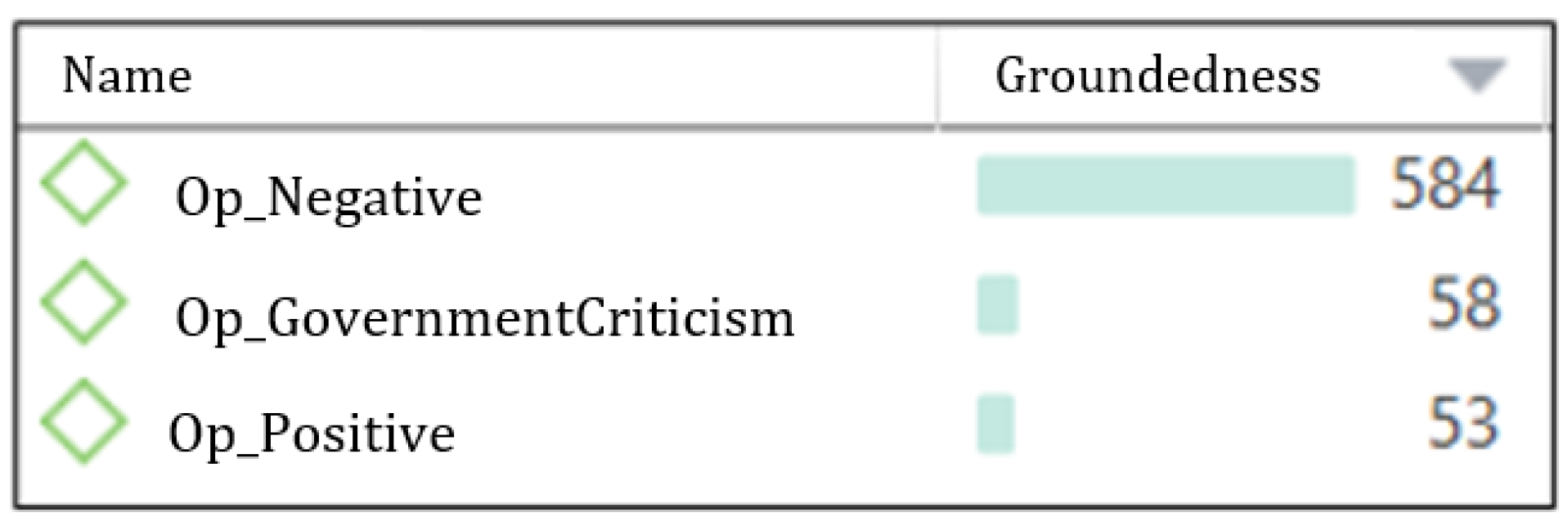

Firstly, it is important to note the different codes and quotes that emerged during the analysis. Following the application of the inductive coding, a total of 10 codes were identified. These were then grouped into two dimensions, depending on the meaning they contributed. In the first instance, three codes for value bias were identified, indicating whether the tweet analysed referred to a positive or negative opinion on the law in question, or whether it was directly an opinion that expressed criticism of the government. Tweets that did not explicitly adopt a position were excluded from the coding process. As demonstrated in

Figure 1, a significant proportion of coded tweets expressed a negative evaluation of the law; however, the majority of these did not explicitly articulate their stance.

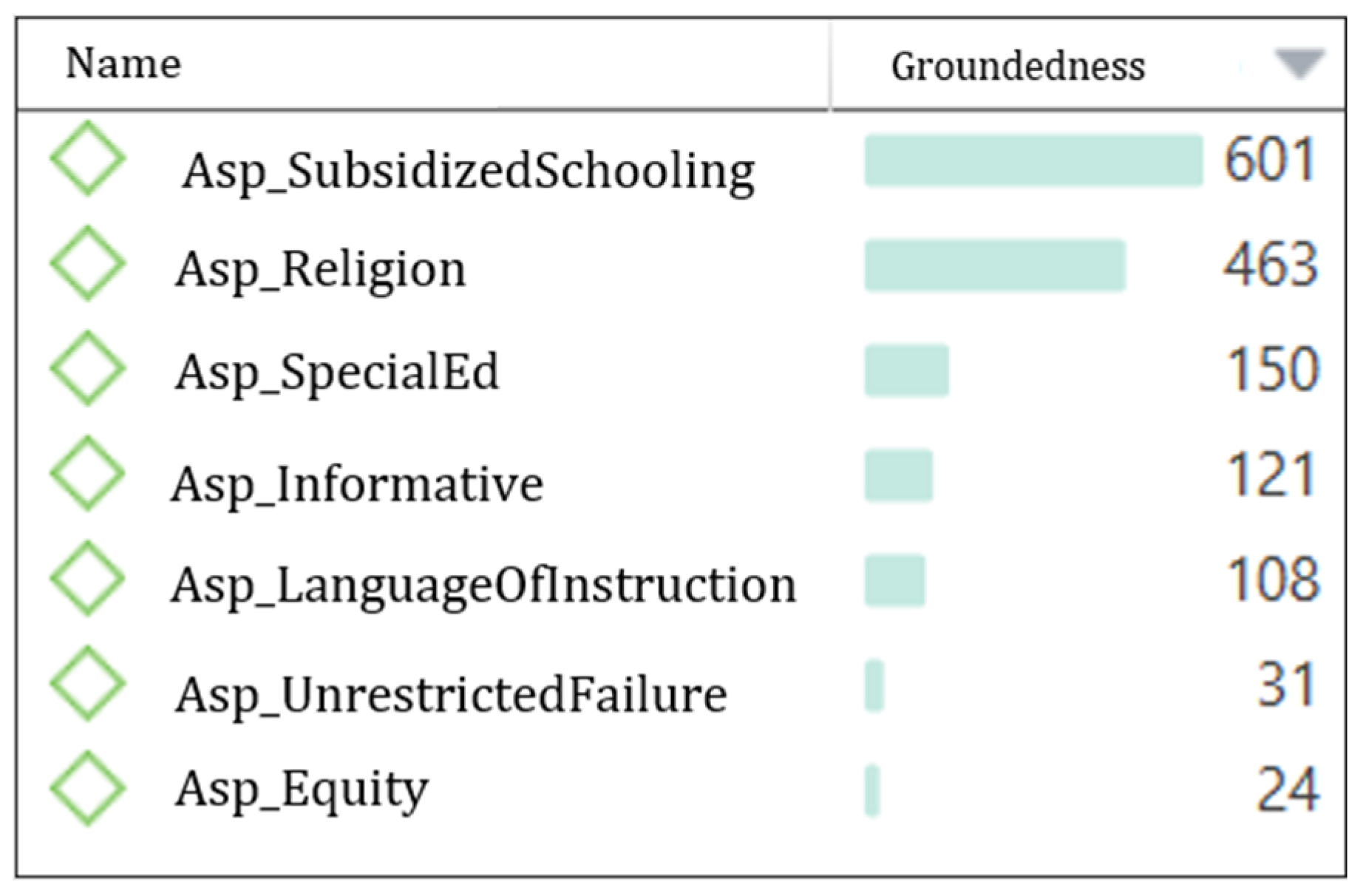

Conversely, following the coding process, a total of seven codes emerged that addressed the various aspects, at the level of semantic content, of these opinions on LOMLOE. The following were identified:

Asp_SubsidizedSchooling: With regard to the content of the tweets, the focus is on educational concerts;

Asp_Religion: The primary content pertains to a religious nature, whilst the secondary content concerns educational concerts as referenced in tweets;

Asp_SpecialEd: reference is made to centres catering to pupils with special educational needs (SEN). The content of these tweets is predominantly of a religious nature;

Asp_Informative: The objective of this text is to provide a balanced and unbiased overview of the pertinent legislation;

Asp_LanguageOfInstruction: The primary theme that is to be established is that of the vehicular language;

Asp_NoLimitOnFailedSubjects: The following observations pertain to the conditions for promotion;

Asp_Equity: The following discussion pertains to the utilisation of the term “equity” in the context of education.

As illustrated by the rooting of the codes in

Figure 2, certain categories emerge that are clearly distinguished from the others. These categories are evident in the discourse of the tweets and are thus understood to represent the issues that have generated the most significant social concern, namely aspects pertaining to subsidised education (D1:25), those of a religious nature (D1:44), and special education (D4:1).

#celaa #LOMLOE They want to get rid of all religious institutions just like they did in their beloved Second Republic, art. 26 II R.E. Sectarian, red, sectarian and totalitarian constitution, that’s where we’re heading: (D1:44).

The present situation has been caused by the attack on state-subsidised schools, the elimination of the freedom of choice for families, the diminution of educational plurality, and the replacement of special education and Spanish as the language of instruction. There are numerous reasons for this. The hashtag #WeWillStopCelaaLaw (D4:1) is used to denote opposition to the CelaáLaw, with the more expansive StopCelaáLaw and #MorePluralVoices also being used to voice similar sentiments.

Table 2, which analyses the relative frequencies according to each of the documents grouped by hashtag and the codes used in the categorisation of the citations, shows that this trend is maintained in the case of Asp_SubsidizedSchooling, with a majority in percentage terms with respect to the other codes used or being among the most used codes. However, a considerable variation in the observed percentages can be observed depending on the document under consideration, ranging from 24.53% in the case of #CelaáLaw to 85.71% of #MorePluralVoices.

In the case of Asp_Religion and Asp_SpecialEducation, however, the results differ depending on the number of citations analysed in each document. In the initial case, tweets pertaining to religious affairs, the documents exhibiting the highest percentage are #REIsMore, with 67.65% of the tweets in this document referring to this particular type of content, and #WeWillStopCelaaLaw, with 50.72%. With regard to the remaining documents, the range is from 5% to 13.21%, which is comparatively low for the second category with the most coded tweets. In the second case, Asp_SpecialEducation, no document is particularly distinguished from the others. The document entitled ‘#EquityEducationFuture’ received the highest percentage of citations, with 28.57%, while the document entitled ‘#REIsMore’ received the lowest, with 4.52%.

As demonstrated, the remaining codes or subjects that emerged exhibited a heterogeneous utilisation of each of the issues raised in the law; however, none of them were particularly distinguished from the others. It is noteworthy that, as would be anticipated, tweets that made reference to the law in an informative manner accounted for the highest number of citations in the sets of tweets whose hashtags lacked positioning: As demonstrated in

Figure 1, hashtag #Celaá has been identified as a primary topic of discussion, with a percentage of 46.28%. In addition, the hashtags #CelaáLaw and #Lomloe have been identified as secondary topics, with approximate percentages of 18% and 17%, respectively.

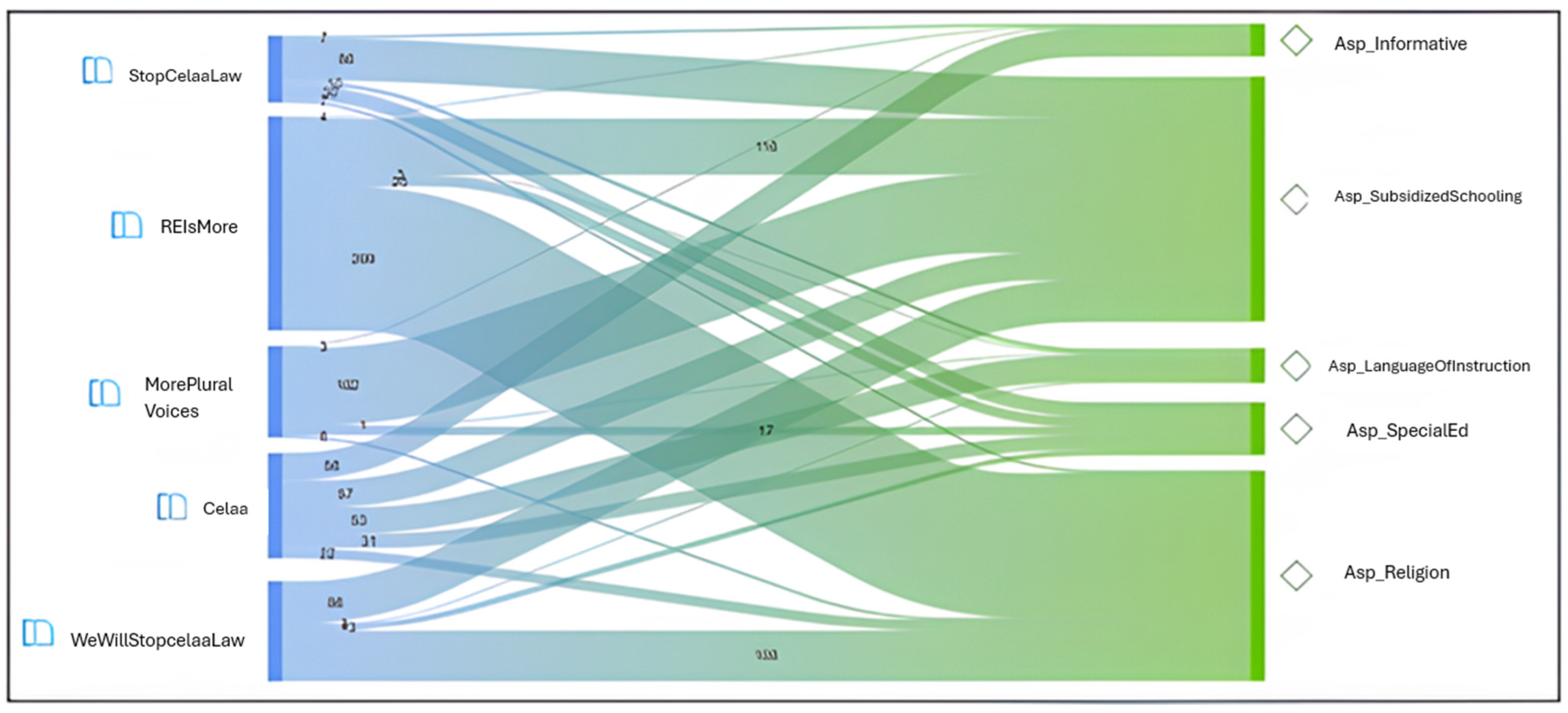

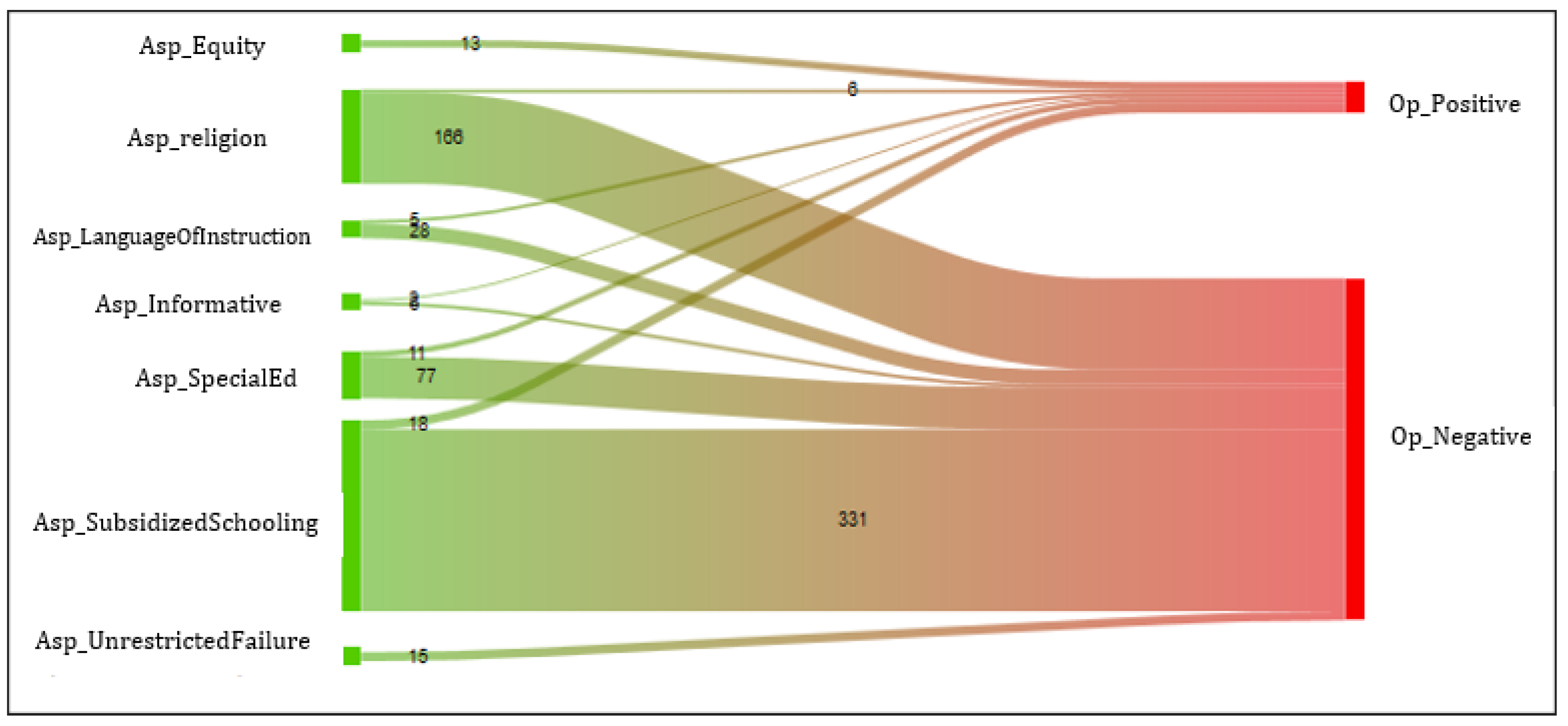

Conversely, examination of the Sankey diagram (

Figure 3), derived from the preceding analysis, provides graphical corroboration of the observations concerning the utilisation of codes. It is evident that the majority of the mentions in the highlighted tweets were attributable to Asp_SubsidizedSchooling and Asp_Relgion. However, in this particular instance, the document in which the majority of these tweets can be found would be #REIsMore, in accordance with

Table 1, which demonstrated the group of documents with the highest number of tweets.

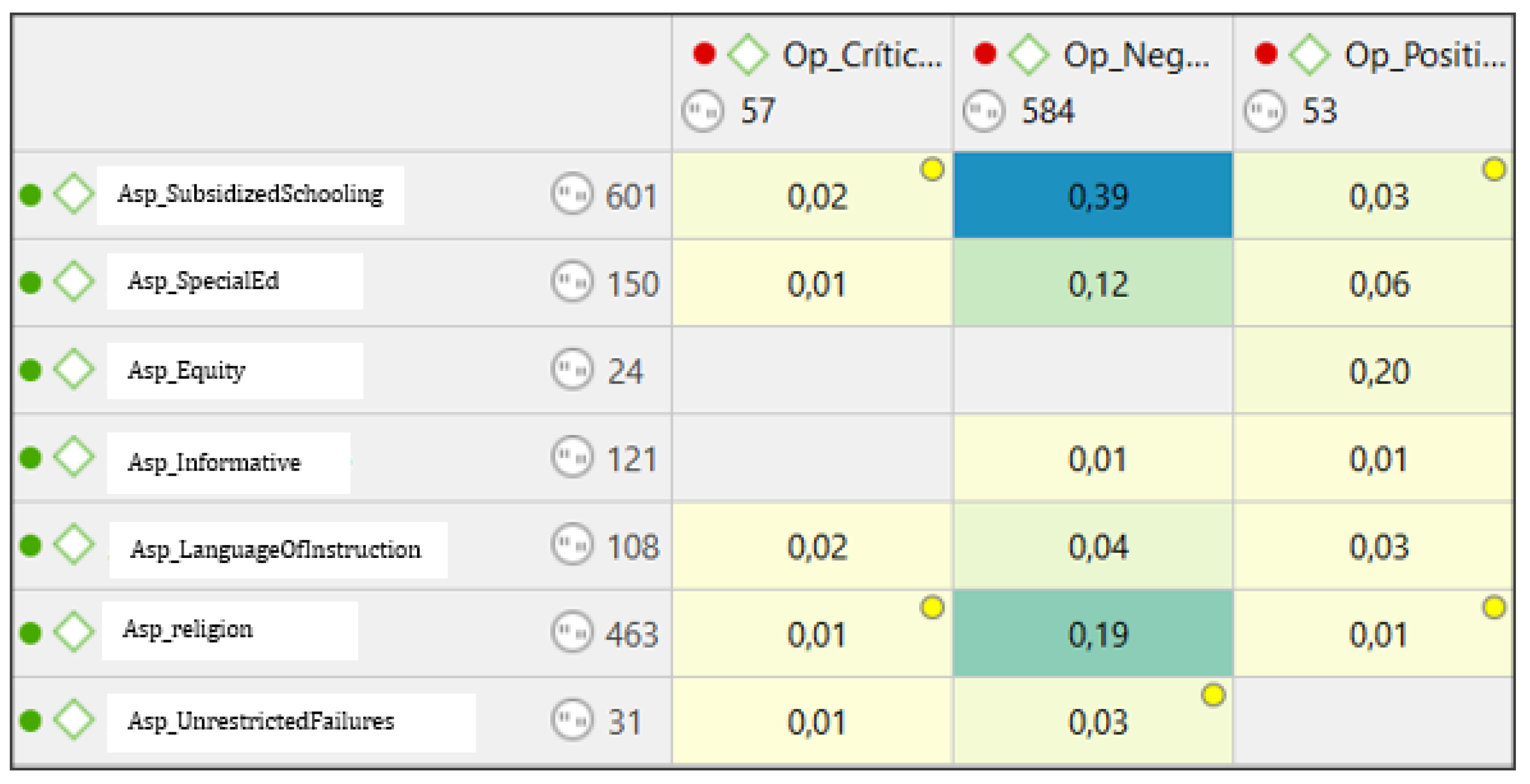

The same pattern continues when establishing the co-occurrence of codes between each of those appearing in the aforementioned groups, the evaluative and thematic ones (

Figure 4). A close examination of the data reveals that tweets discussing aspects related to private education and religion are the ones that stand out from the rest in terms of co-occurrence. However, it should be noted that this phenomenon is only evident in tweets that offer a negative assessment (Op_Negative) of the CelaáLaw. Specifically, there is a co-occurrence of 0.39 and 0.19 with Asp_SubsidizedSchooling and Asp_Religion, respectively. Tweets pertaining to special education merit mention, on this occasion due to their demonstration of a modest co-occurrence of 0.12.

As was the case in the preceding instance, wherein relative frequencies were the subject of assessment, the Sankey diagram (

Figure 5) of co-occurrences manifestly evinces the robust relationship between negative opinions concerning the law and religious issues, and those concerning state-subsidised private education.

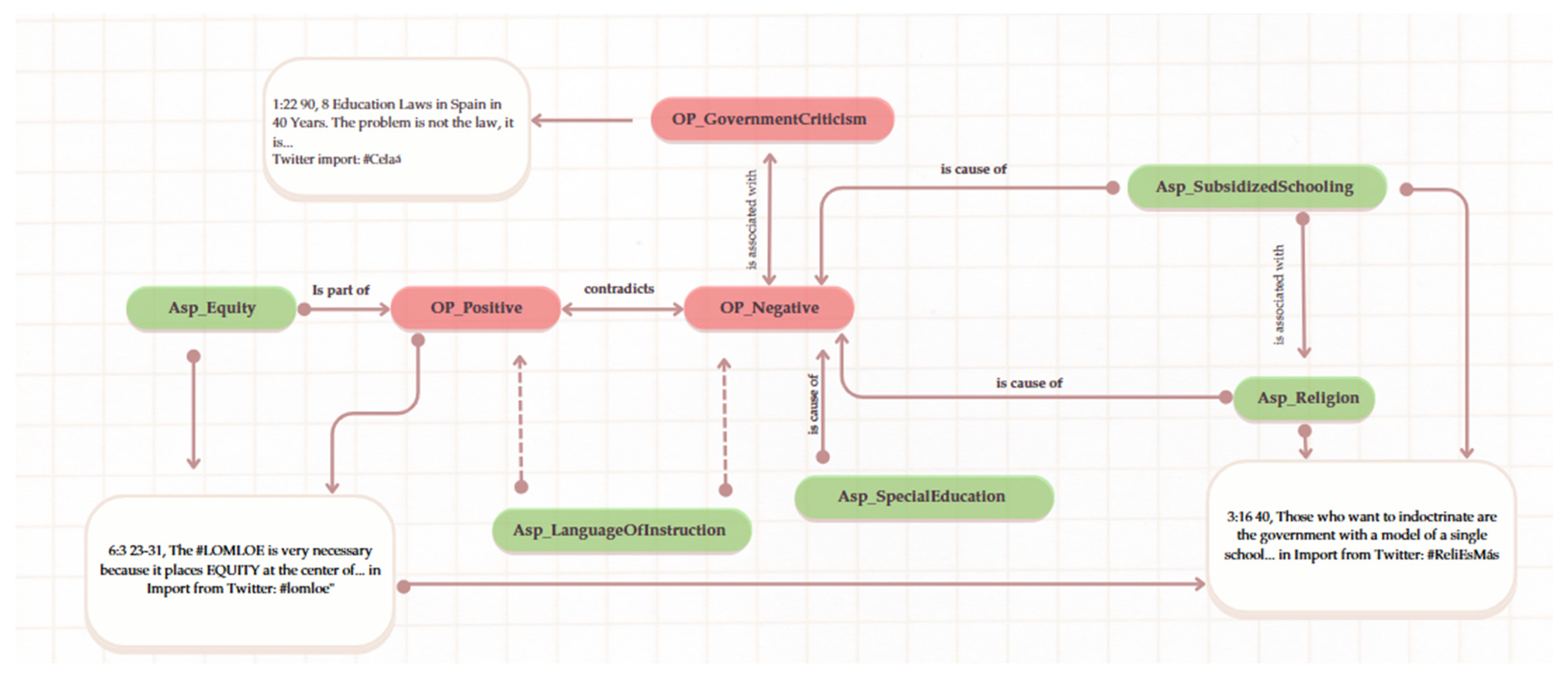

Furthermore, during the coding and analysis of the data, various arguments emerged that are presented in the semantic network generated for this purpose (see

Figure 6). It is evident that the primary source of the negative sentiments expressed towards the legislation is the existence of issues that have been explicitly or implicitly raised. These include, but are not limited to, social media posts pertaining to subsidised education, those of a religious nature, and those referring to special education. Moreover, this negative opinion is closely associated with a critical evaluation of the government. Nevertheless, it should be noted that not all opinions expressed in this regard are specifically against the law; rather, they adopt a more general critical stance (D1:22) with regard to aspects such as investment in education or the work of the two main political parties.

The following eight education laws have been enacted in Spain over the course of the past 40 years. The crux of the issue lies not in the legal framework per se, but rather in the failure of the PP and PSOE to prioritise investment in public education, a sector that, it should be noted, receives a mere 4% of GDP, placing Spain at the very nadir of the European ranking. The allocation of financial resources is to be redirected from the sphere of parliamentary bureaucracy to that of investment in the populace. The hashtag #celaa was used (D1:22).

![Socsci 14 00415 i005]()

Have you read that the LOMLOE will end Spanish in schools? Have you heard that it is an attack on state-subsidised education? Have you been told that the new law is indoctrinating? DON’T BELIEVE IT

![Socsci 14 00415 i006]()

We tell you the truth about the #LOMLOE. Follow the thread

![Socsci 14 00415 i007]()

#EquityEducationFuture

![Socsci 14 00415 i008]()

![Socsci 14 00415 i009]()

pic.twitter.com/o0Z2FV3V2v (D7:1).

I am forbidden from speaking Spanish in Spain. Celaa is violating the Constitution by not considering Castilian Spanish an official language. Go to hell #Celaa #StopCelaáLaw okdiario.com/espana/ley-cel… (D1:27).

In addition, a conspicuous contradiction, or at the very least, a disparity of positions, is evident in the juxtaposition of tweets that articulate a negative evaluation of the law with reference to the three aspects emphasised in this analysis (subsidised education, religion and special education) and a fourth category for which the code Asp_Equity was utilised:

The #LOMLOE is badly needed because it puts EQUITY at the heart of the education system. And stick to the facts: It is a lie that the new law closes special education centres.

![Socsci 14 00415 i010]()

@CelaaIsabel #SesiónDeControl

![Socsci 14 00415 i009]()

pic.twitter.com/RwP3gU1rYs (D6:3).

It is important to note that the remaining citations do not reach a sufficient saturation point to be considered in this analysis. This is partly because they do not have a profound manifestation in the data collected, which leads to the inference that the main topics of discussion are those that have been repeatedly presented in the analysis: The following variables have been identified: Asp_SubsidizedSchooling, Asp_Religion and Asp_SpecialEducation.

4. Discussion

Firstly, with regard to the much-debated right to education, Article 109 of the LOMLOE is worthy of particular note, specifically in relation to the planning of the network of schools, which has undergone some changes. In point 1 of the LOMLOE, the obligation of public authorities to guarantee the right of all to education is stated. This obligation is to be fulfilled through a sufficient number of public places, under conditions of equality and the individual rights of pupils, parents and legal guardians. The LOMCE did not include this guarantee.

The implementation of the LOMLOE (Organic Law for the Modification of the LOE) in Spain marks a significant shift toward a more inclusive, competency-based, and equitable education system. According to the European Commission’s Eurydice network (

European Commission 2021), the law emphasizes the development of key competencies over rote learning, promotes co-education, and strengthens the role of public education. The

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (

2021) highlights that the LOMLOE reinforces inclusive education by mandating that all students, regardless of ability, have access to mainstream education with appropriate support.

In the context of student admission, amendments have been implemented to elucidate that in instances where capacity is limited, admission will be determined by the priority criteria of siblings already enrolled, proximity and income. Subsequent to this, large families and other pertinent circumstances will be given due consideration. As demonstrated in Article 84 of the law, the government is most eager to modify this particular aspect, a point of contention among proponents of subsidised education. These individuals perceive it as a menace to ’freedom of choice for families’, a right they assert is entrenched in Article 27 of the Constitution. However, this can often come up against issues such as ensuring educational equity as advocated by organisations such as

UNESCO (

2025) or the

United Nations (

2023), since freedom of school choice runs the risk of forming ideological ghettoes (

Witenstein and Abdallah 2022).

As

Cotino Hueso (

2012, p. 9) observes, education has emerged as a pivotal arena for political discourse, particularly in the context of religious disagreements (

Garcés 2021). While the theological issue does not exclusively concern state-subsidised private schools, as it also affects public schools, further research is required to ascertain the full extent of its impact on educational institutions. The LOMLOE proposes a significant alteration to the prevailing approach, namely the exclusion of this subject from the calculation of the average mark, and the elimination of any alternative subject. This constitutes the only amendment pertaining to the subject; all other elements will remain unaltered, and the subject will continue to be available to all students wishing to undertake it (

Watkins and Donnelly 2020). Conversely, it puts forward the concept of Civic and Ethical Values Education, encompassing subjects related to the Spanish Constitution, fostering knowledge and respect for human rights, education for sustainable development, equality between men and women, the value of respect for diversity and the social value of taxes, promoting critical thinking and a culture of peace and non-violence (

Torres-Soto et al. 2025;

Maclatchy et al. 2025).

The government has emphasised the following points: The LOMLOE does not modify the mechanism for the selection and articulation of preferences for educational institutions by families. However, it does reinforce the guarantees of a balanced distribution of pupils through the general planning of education, thereby strengthening the role of the Schooling Commissions to ensure a balanced and transparent distribution of demand and school enrolment, thus avoiding selection and exclusion biases in the creation and allocation of places’. In line with

OECD (

2023), education systems should respond appropriately to students’ needs and contribute to their overall development. In this regard, the LOMLOE states in point 1 of Article 84 that it maintains ’the freedom of choice of school by parents or legal guardians’ as the guiding principle for school choice, but adds as a new feature that ’the necessary measures shall be taken to prevent the segregation of students on socio-economic or other grounds’. It is also notable that point 7 has been added, which gives priority in admission to proximity of the school to the home or per capita income. These elements were also included in the LOMCE, but which it does not prioritise. Furthermore, and this is also a novel development, Article 86 stipulates in point 1 that the administrations are obliged to establish ’areas of influence, determined after consultation with the local administrations, in such a way as to ensure the effective application of the priority criteria of proximity to the home and covering, as far as possible, a socially heterogeneous population.’ The article further elaborates that the admission guarantee committees, which are mandated to intervene in instances where a school experiences an excess demand for places relative to its capacity, have been in existence for some time. These committees are required to ensure the avoidance of segregation among pupils based on socio-economic or other criteria, and are tasked with proposing measures deemed necessary to the relevant education authorities (

Eden et al. 2023). In particular, they shall ensure the balanced presence of students with specific educational support needs or who are in a disadvantaged socio-economic situation in publicly funded centres within their area of responsibility. This follows one of the main recommendations of

UNESCO (

2025), taking into account the elimination of barriers to educational inclusion and equity.

The LOMLOE will also not permit subsidies to be granted to schools that segregate their students by gender. The LOMCE established for the first time in law that ’the admission of male and female students or the organisation of education differentiated by gender does not constitute discrimination’ (

Ganimian and Murnane 2016). This ruling paved the way for subsidies for these schools. The LOMLOE repeals this expression and advocates for the subsidisation of ’preferably mixed schools with co-education projects’. It further stipulates that educational institutions implementing ’differentiated education’ are obligated to substantiate their adherence to principles of gender equality.

In conclusion, a further novel feature of the LOMLOE is that it will prohibit the transfer of public land for the purpose of constructing subsidised private schools. This measure is associated with the social demand that has been previously delineated, in addition to the planning of the network of schools.

5. Conclusions

The response to this proposed legislation has been immediate and widespread, with significant activity observed on various social media platforms. A notable segment of the Spanish population, particularly those associated with private or subsidised education, challenges the merits of the law and disregards it as incompatible with democratic principles, primarily due to its impact on Castilian Spanish and the modifications to special education (

Gómez-Jiménez 2021). Despite the government’s assertions that the official status and presence of the state language is assured, other political parties have expressed concerns that the modifications made to the text and the elements that have been eliminated (e.g., the categorisation of ’vehicular’ language) in the recent educational reform may compromise the significance of Spanish in the classroom.

Conversely, state-subsidised private schools have mobilised against the reform due to various elements included in the report. One of these is the express prohibition on these centres charging compulsory extra fees to families. It is this sector of the educational community which has drawn attention to the fact that certain key references which were present in the regulations still in force have been removed. The LOMCE stipulated that the authorities should devise educational provision plans with due consideration for the extant provision of public and private subsidised centres and ’social demand’. The latter element was considered essential by subsidised institutions in order to increase the number of places or maintain subsidies if there was demand, and will now no longer appear in the law. The recently introduced regulation underscores the commitment to ensure education is provided through the adequate provision of public places. Furthermore, the document stipulates that the allocation of land for educational infrastructure will be constrained to publicly owned properties. It also underscores the promotion of a systematic augmentation in the capacity of publicly owned educational institutions.

Another area that has generated considerable controversy is that relating to repeating and passing courses. The text eliminates the possibility of repetition in any year of primary school. Students are permitted to remain in the same year in the second, fourth and sixth years. In secondary school, the new law permits the completion of the year with two failing grades ’in exceptional circumstances’, a provision analogous to that of the Bachillerato, wherein students can obtain their qualification despite failing one subject. In the ESO context, the text stipulates that students will be promoted to the subsequent year when the teaching team deems that the nature of the subjects failed to enable them to successfully continue with the following year. The document states that remaining in the same year should be understood as an exceptional measure. It goes on to explain that this may only be used once in the same year and twice at most throughout compulsory education.

The Ministry and the governing parties have asserted that the objective is to reduce the rate of school dropout, while the main opposition parties contend that the intention is to diminish the significance of successfully completing courses by permitting students who fail to meet the stipulated objectives to progress to the subsequent year.

Limitations

One of the main limitations of this study lies in the nature of the sample used, which is composed exclusively of Twitter posts. Although this social network offers an immediate and dynamic window into public opinion, its use implies an inherent bias, as it does not fairly represent the entire Spanish population, especially those sectors that are less digitally active or have less access to technology. Moreover, the analysis focused on a very specific time period—the weeks in which the LOMLOE was debated and approved—which limits the possibility of observing the evolution of social discourse in the medium and long term. Another important limitation is the subjective interpretation of the messages, since, despite the use of tools such as ATLAS.ti and grounded theory methodology, qualitative analysis always involves a degree of interpretation on the part of the researcher. Furthermore, the study does not delve into the verification of the identity or representativeness of the senders of the messages, which could influence the validity of the conclusions. Finally, the focus on specific hashtags may have excluded other forms of expression relevant to the law, thus reducing the diversity of the discourse analysed.

#publicschool #subsidizedschool #schools #celaalaw #celaa #educationlaw #education #state #secularschool #podemos #VoxIsShit (D1:25).

#publicschool #subsidizedschool #schools #celaalaw #celaa #educationlaw #education #state #secularschool #podemos #VoxIsShit (D1:25). Have you read that the LOMLOE will end Spanish in schools? Have you heard that it is an attack on state-subsidised education? Have you been told that the new law is indoctrinating? DON’T BELIEVE IT

Have you read that the LOMLOE will end Spanish in schools? Have you heard that it is an attack on state-subsidised education? Have you been told that the new law is indoctrinating? DON’T BELIEVE IT We tell you the truth about the #LOMLOE. Follow the thread

We tell you the truth about the #LOMLOE. Follow the thread  #EquityEducationFuture

#EquityEducationFuture

pic.twitter.com/o0Z2FV3V2v (D7:1).

pic.twitter.com/o0Z2FV3V2v (D7:1). @CelaaIsabel #SesiónDeControl

@CelaaIsabel #SesiónDeControl  pic.twitter.com/RwP3gU1rYs (D6:3).

pic.twitter.com/RwP3gU1rYs (D6:3).