Mothers’ Perceptions of Interactions in Animal-Assisted Activities with Children Exposed to Domestic Violence in Shelters: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

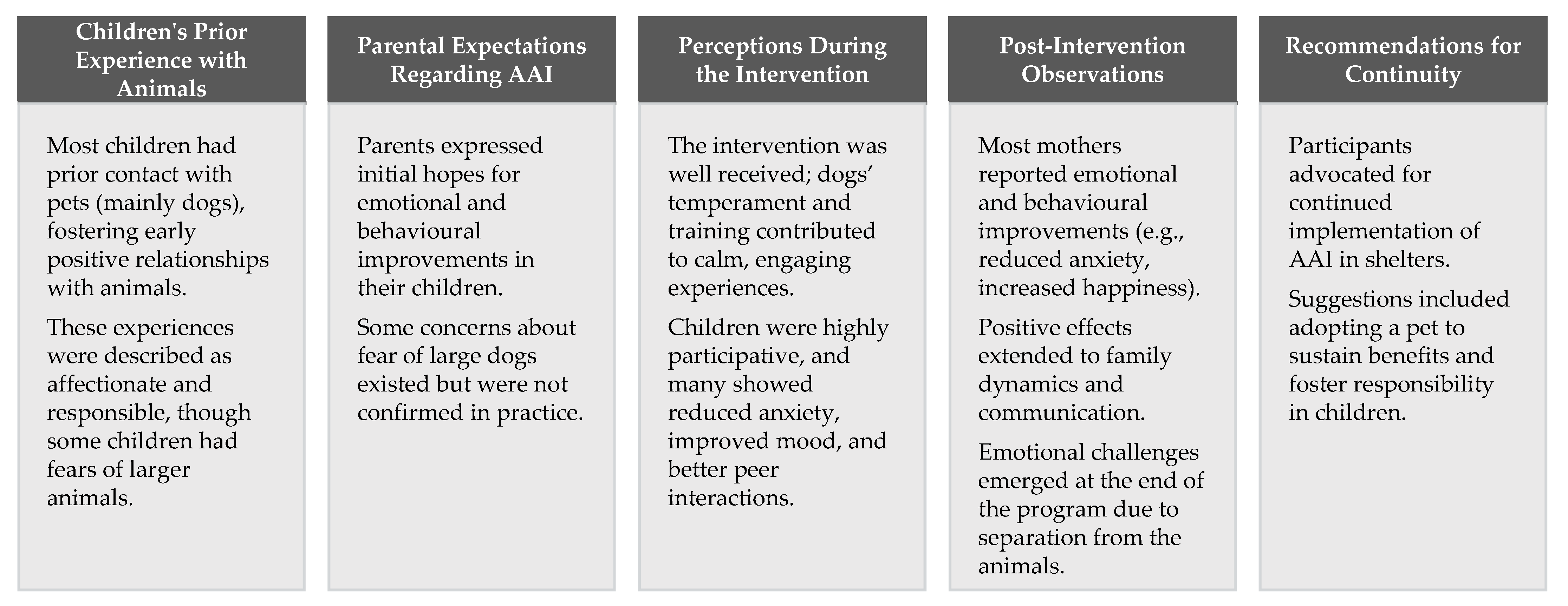

- To understand mothers’ perceptions regarding their children’s prior contact with pets.

- To identify mothers’ initial expectations regarding their children’s participation in the intervention.

- To explore mothers’ observations during the AAI sessions.

- To understand mothers’ perceptions of their children’s behavior during

Contextual Framework of the Study

2. Method

2.1. Sample

2.2. Instruments

- Has your child ever had contact with a pet? If so, how would you describe their relationship with the animal?

- What were your initial expectations regarding your child’s participation in this intervention?

- Can you describe what you observed during the sessions with the animals?

- How did your child behave throughout the intervention period?

- Did you notice any changes in your child after the intervention?

- How would you describe your relationship with your child in recent months?

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Data Treatment and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Parents’ Perceptions About Their Children’s Previous Contact with a Pet

“Yes, with sheep, goats, and chickens.”(M1)

“Yes, we had a female dog before coming here.”(M5)

“Yes, they had contact with a pet in Angola; we had a puppy at home.”(M6)

“If they are large dogs, the youngest would be afraid, but with smaller ones, it’s not the case.”(M3)

“He has a very good connection; he likes dogs a lot; he loved the female dog, giving her kisses and hugs.”(M4)

“They [daughters] interacted well with the puppy, taking care of it. When I say they took care of it, I mean they bathed it, fed it, and took it to the veterinarian.”(M6)

3.2. Initial Expectations of Parents Regarding Their Children’s Participation in the Intervention

“For them to be happier, because I know they really like animals, and since we came here, they haven’t had the opportunity, so I hoped to see them happier. They missed contact with animals, so I also hoped that through the intervention, they would miss it less.”(M1)

“When we learned there would be an animal-assisted intervention, it was a joy for them, so my expectation was that they would become happier and form a special bond with the animals.”(M5)

“As you know, he is autistic; my expectation was that he would show a bit more interest in the dog.”(M6)

“I was a bit worried because the other dog my son was used to was smaller, but for me it was very positive for him to see that there are various types of dogs, so he had the opportunity to meet other breeds… I found the experience very valid.”(M4)

“At first, I was apprehensive; I thought the large dogs would cause fear since the dog we had was very small, but that didn’t happen. Right from the first experience they had with the dog, it went well; they interacted nicely.”(M6)

3.3. Observations of the Mothers During Intervention Sessions with the Animals

“You did a kind of rotation, bringing animals of various sizes, and overall, I think this was very positive. The animal had a very protective instinct; dogs have this protective instinct, and the children, at least most of them that I saw, felt very comfortable.”(M4)

“The little dog was very gentle with all the children; they were very calm. It’s said that dogs are man’s best friend for a reason.”(M5)

“The dogs were very well trained, so everything was very well done: all the sessions with the dog, the children, and even with the adults. I found it very rewarding.”(M6)

“Believe it or not, they are sleeping, and from time to time I hear them say ‘pea, whatever, grab the ball, grab the ball.’ They’re dreaming about what they did with the little dog in the program.”(M1)

“There were games with the dog; one game involved hiding treats, and my daughters were hiding the food, which was eventually found by the dog. It went well, and I, as a mother, liked it, and they enjoyed the intervention too.”(M6)

“You could really see the joy in their [the children’s] eyes, that spark of being there with the animal, that contact they didn’t have and now regained; it was total joy whenever they saw the dog—they jumped with happiness.”(M1)

“My son couldn’t sit still; he always wanted to participate in everything they were doing, always holding onto the little dog, he loved it and didn’t want to let go.”(M2)

“My son is quite shy, so in my opinion, during the sessions, he felt more at ease and connected more with the other children”.(M5)

“My daughters were very calm during the interventions; one of them is finishing the project to graduate from school and has been very anxious, but during those moments, she was able to distract herself a bit”.(M6)

“He was highly participative; he always wanted to do everything”.(M2)

“I cannot force him to interact more; it has to be gradual. However, I thought he did well in terms of relating to or contacting the animal. Of course, it wasn’t the same as with the other children, but given his limitations, it was quite valid”.(M4)

“They [the children] participated very well; they were very engaged; in all the games, they always seemed very interested”.(M6)

3.4. Observations of the Mothers After the Intervention with the Animals

“They were already lively, so not much changed”.(M3)

“It changed completely; he always seemed unhappy until the dog appeared. After that, he was all joy”.(M5)

“Their anxiety has decreased substantially; they were very anxious girls, and I think this helped a lot”.(M6)

“The intervention made us even closer; sometimes something would happen, and I could not be there with them, but that’s because we have tasks to complete within the schedule. So, if they needed anything, they would immediately call for me, and I would rush over… I would stand there admiring them, smiling, playing, and then when they needed me, they ran, ‘Mom, come here!’ and I would rush over”.(M1)

“He [son] would run out of the intervention to tell me everything that happened; it helped us communicate more”.(M2)

“She and her sister interacted much more; they talked about what happened there, so it helped a lot in their relationship”.(M6)

“The last time he saw ‘Ervilha’ [the dog’s name], my son cried all the way to the room, ‘Mom, ‘Ervilha’ isn’t coming back,’ and I said, ‘Why not?’ It’s over, Mom; she’s not coming back,’ crying desperately, and I said, ‘Oh, son, don’t cry; she will return’”.(M1)

“I have really enjoyed it, but the part of saying goodbye is complicated; my youngest doesn’t want her to leave and ends up crying, and I have to calm him down about the longing…”.(M3)

“I think this program should be implemented; this contact with animals is very good, you know; the children love it, and they end up learning this way. Animals always have something to teach, especially dogs, regarding loyalty and other things; I find this contact with children very important, it’s different, and I believe it’s very worthwhile”.(M4)

“I think this program should be implemented; I believe it would be beneficial for both mothers and children”.(M5)

“One thing, a suggestion of mine because I saw the difference in them, the before and after. Before, they did not have any pets here, and since the dogs started coming, it has made a significant difference. So, what I would suggest is, why not adopt small dogs, like Chihuahuas or Yorkshire Terriers, for the shelter, so the children can take care of them, give them water, and bathe them? I think it would be an interesting way for them to learn responsibility from a young age”.(M1)

“(…) It would be great if the shelters had pets. It would be wonderful for the children and even for us mothers”.(M6)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Almeida, Telma Catarina, Ana Isabel Sani, and Rui Abrunhosa Gonçalves. 2022. Children exposed to interparental violence: A study of Portuguese children aged 7–9 years. Suma Psicológica 29: 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosi Caterina, Charles Zaiontz, Giuseppe Peragine, Simona Sarchi, and Francesca Bona. 2019. Randomized controlled study on the effectiveness of animal-assisted therapy on depression, anxiety, and illness perception in institutionalized elderly. Psychogeriatrics 19: 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachi, Keren, Joseph Terkel, and Meir Teichman. 2012. Equine-facilitated psychotherapy for at-risk adolescents: The influence on self-image, self-control and trust. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry 17: 298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baird, Robert, Emily Berger, and Christine Grové. 2023. Therapy dogs and school wellbeing: A qualitative study. Journal of Veterinary Behavior 68: 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balluerka, Nekane, Alexander Muela, Nora Amiano, and Miquel A. Caldentey. 2014. Influence of animal-assisted therapy (AAT) on the attachment representations of youth in residential care. Children and Youth Services Review 42: 103–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, Gia Elise, and Silvia Dominguez. 2017. Longitudinal growth of post-traumatic stress and depressive symptoms following a child maltreatment allegation: An examination of violence exposure, family risk and placement type. Children and Youth Services Review 81: 368–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardin, Laurence. 1977. Análise de Conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70. [Google Scholar]

- Beavers, Anna, Antoinette Fleming, and Jeffrey D. Shahidullah. 2023. Animal-assisted therapies for autism. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care 53: 101478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, Marty, and Danelle Morton. 2002. The Healing Power of Pets: Harnessing the Amazing Ability of Pets to Make and Keep People Happy and Healthy. New York: Hyperion Books. Available online: https://archive.org/details/healingpowerofpe0000beck (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Bert, Fabrizio, Maria Rosaria Gualano, Elisa Camussi, Giulio Pieve, Gianluca Voglino, and Roberta Siliquini. 2016. Animal assisted intervention: A systematic review of benefits and risks. European Journal of Integrative Medicine 8: 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosacki, Sandra, Christine Yvette Tardif-Williams, and Renata P. S. Roma. 2022. Children’s and adolescents’ pet attachment, empathy, and compassionate responding to self and others. Adolescents 2: 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, Constança, Maria Sampaio, Valéria Sousa-Gomes, Marisalva Fávero, and Diana Moreira. 2025. Effects of Animal-Assisted Therapy for Anxiety Reduction in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine 14: 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, Helen, Kelly Rushton, Karina Lovell, Rebecca McNaughton, and Anne Rogers. 2019. ‘He’s my mate you see’: A critical discourse analysis of the therapeutic role of companion animals in the social networks of people with a diagnosis of severe mental illness. Medical Humanities 45: 326–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, Page Walker, and Angela Lavery. 2020. Animal-assisted activities for children with autism spectrum disorders: Parent insights. Human-Animal Interaction Bulletin 8: 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, Jane Elisabeth Mary, Lisa Chiara Fellin, Stavroula Mavrou, Joanne H. Alexander, Vasiliki Deligianni-Kouimtzi, Maria Papathanassiou, and Judith Sixsmith. 2023. Part of the family: Children’s experiences with their companion animals in the context of domestic violence and abuse. Journal of Family Violence, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, Rebekah L., Caitlin Baselmans, Tiffani J. Howell, Carol Ronken, and David Butler. 2024. Exploring the benefits of dog-assisted therapy for the treatment of complex trauma in children: A systematic review. Children 11: 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Elizabeth A., Anna M. Cody, Shelby Elaine McDonald, Nicole Nicotera, Frank R. Ascione, and James Herbert Williams. 2018. A template analysis of intimate partner violence survivors’ experiences of animal maltreatment: Implications for safety planning and intervention. Violence Against Women 24: 452–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, Daniela, Maria Emília Leitão, and Ana Isabel Sani. 2024. Domestic violence victimization risk assessment in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Social Sciences 13: 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, Tracy J., Diana Davis, and Jacquelyn Pennings. 2012. Evaluating animal-assisted therapy in group treatment for child sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 21: 665–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, Aubrey H., Alan M. Beck, and Zenithson Ng. 2019. The state of animal-assisted interventions: Addressing the contemporary issues that will shape the future. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16: 3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehrke, Ellen Kaye, Alice E. Noquez, Peggy L. Ranke, and Michael P. Myers. 2018. Measuring the psychophysiological changes in combat Veterans participating in an equine therapy program. Journal of Military, Veteran and Family Health 4: 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, Crystian Moraes Silva, Amanda Doring Semedo, Maria Eduarda Teixeira Caetano, and Rosana Suemi Tokumaru. 2023. Intervenções assistidas por animais: Revisão e avaliação de estudos latino-americanos. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial 29: e0155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, Elías Guillen, Laia Sastre Rodríguez, Pilar Santamarina-Perez, Laura Hermida Barros, Marta Garcia Giralt, Eva Domenec Elizalde, Fransesc Ristol Ubach, Miguel Romero Gonzalez, Yeray Pastor Yuste, Cristina Diaz Téllez, and et al. 2022. The benefits of dog-assisted therapy as complementary treatment in a children’s mental health day hospital. Animals 12: 2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, Roxanne D., Shelby Elaine McDonald, Kelly O’Connor, Angela Matijczak, Frank R. Ascione, and James Herbert Williams. 2019. Exposure to intimate partner violence and internalizing symptoms: The moderating effects of positive relationships with pets and animal cruelty exposure. Child Abuse & Neglect 98: 104166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hediger, Karine, Stefan Thommen, Cora Wagner, Jens Gaab, and Margret Hund-Georgiadis. 2019. Effects of animal-assisted therapy on social behaviour in patients with acquired brain injury: A randomised controlled trial. Scientific Reports 9: 5831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horta, Sandra. 2022. Respostas sociais à violência contra animais de companhia. In Animais e Pessoas. Edited by Mauro Paulino, Sandra Horta and Pedro Emanuel Paiva. Lisboa: Pactor, pp. 137–50. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, Tiffani J., Suzanne Hodgkin, Corina Modderman, and Pauleen C. Bennett. 2021. Integrating facility dogs into legal contexts for survivors of sexual and family violence: Opportunities and challenges. Anthrozoös 34: 863–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalongo, Mary Renck, and Lorraine J. Guth. 2023. Animal-assisted counseling for young children: Evidence base, best practices, and future prospects. Early Childhood Education Journal 51: 1035–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, Giovanna, Anna Costagliola, Renato Lombardi, Orlando Paciello, and Antonio Giordano. 2023. Human-animal interaction in animal-assisted interventions (AAI) s: Zoonosis risks, benefits, and future directions—A one health approach. Animals 13: 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, Camila Moura, Prado Emanuele Silva, Anne Karoline Silveira Flores, Dione Moreira Nunes, Tatiane Morgana Silva, Carolina da Fonseca Sapin, Fernanda Dagmar Martins Krug, and Márcia Oliveira Nobre. 2020. Intervenções assistidas por animais: Efeitos aos cães terapeutas e seres humanos. Archives of Veterinary Science 25: 106–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, Maeve Doyle, Lynette Mackenzie, Meryl Lovarini, Claire Dickson, and Alberto Alvarez-Campos. 2020. Animal assisted therapy for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: Parent perspectives. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 50: 4492–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández, Eduardo, Alba Palacios-Cuesta, Alicia Rodríguez-Martínez, Marta Olmedilla-Jodar, Rocío Fernández-Andrade, Raquel Mediavilla-Fernández, Juan Ignacio Sánchez-Díaz, and Nuria Máximo-Bocanegra. 2023. Implementation feasibility of animal-assisted therapy in a pediatric intensive care unit: Effectiveness on reduction of pain, fear, and anxiety. European Journal of Pediatrics 183: 843–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Hui, and Haomiao Li. 2023. Association between exposure to domestic violence during childhood and depressive symptoms in middle and older age: A longitudinal analysis in China. Behavioral Sciences 13: 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, Ana Rita, Graça Duarte Santos, and Nicole Almeida. 2023. Equine-assisted therapeutic intervention in institutionalized children: Case studies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20: 2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, Shelby Elaine, Elizabeth A. Collins, Anna Maternick, Nicole Nicotera, Sandra Graham-Bermann, Frank R. Ascione, and James Herbert Williams. 2019. Intimate partner violence survivors’ reports of their children’s exposure to companion animal maltreatment: A qualitative study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 34: 2627–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meers, Lieve Lucia, Laura Contalbrigo, William Ellery Samuels, Carolina Duarte-Gan, Daniel Berckmans, Stephan Jens Laufer, Vicky Antoinette Stevens, Elizabeth Ann Walsh, and Simona Normando. 2022. Canine-assisted interventions and the relevance of welfare assessments for human health, and transmission of zoonosis: A literature review. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 9: 899889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muela, Alexander, Josune Azpiroz, Noelia Calzada, Goretti Soroa, and Aitor Aritzeta. 2019. Leaving a mark, an animal-assisted intervention programme for children who have been exposed to gender-based violence: A pilot study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16: 4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, Jennifer L., Elizabeth Van Voorhees, Kelly E. O’Connor, Camie A. Tomlinson, Angela Matijczak, Jennifer W. Applebaum, Frank R. Ascione, James Herbert Williams, and Shelby E. McDonald. 2022. Positive engagement with pets buffers the impact of intimate partner violence on callous-unemotional traits in children. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 37: NP17205–NP17226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, Maria, Eva-Lotta Funkquist, Ann Edner, and Gunn Engvall. 2020. Children report positive experiences of animal-assisted therapy in paediatric hospital care. Acta Paediatrica 109: 1049–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordgren, Lena, and Gabriella Engström. 2014. Animal-assisted intervention in dementia: Effects on quality of life. Clinical Nursing Research 23: 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Haire, Marguerite, Noémie Guérin, and Alison Kirkham. 2015. Animal-Assisted Intervention for trauma: A systematic literature review. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parish-Plass, Nancy. 2008. Animal-assisted therapy with children suffering from insecure attachment due to abuse and neglect: A method to lower the risk of intergenerational transmission of abuse? Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry 13: 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Allie J. D., and Diana McQuarrie. 2008. Therapy Animals Supporting Kids (TASK) Program Manual. Washington: American Human Association. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, Lauren, Kate M. Edwards, Paul McGreevy, Adrian Bauman, Anthony Podberscek, Brendon Neilly, Catherine Sherrington, and Emmanuel Stamatakis. 2019. Companion dog acquisition and mental well-being: A community-based three-arm controlled study. BMC Public Health 19: 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, Kathleen, Lynette Mackenzie, Meryl Lovarini, and Claire Dickson. 2022. Occupational therapy incorporating dogs for autistic children and young people: Parent perspectives. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 85: 859–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, Kerry E., Jessica Bibbo, and Marguerite E O’Haire. 2022. Perspectives on facility dogs from pediatric hospital personnel: A qualitative content analysis of patient, family, and staff outcomes. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice 46: 101534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, Ana Isabel. 2019. Violência sobre as crianças em contexto doméstico: Da dimensão do problema à resposta social. In Criminologia e Reinserção Social. Edited by Fausto Amaro and Dália Costa. Lisbon: PACTOR, pp. 161–75. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, Inês. 2024. Benefícios de uma Intervenção Assistida por Animais no Apoio a Crianças Vítimas de Violência Doméstica [Benefits of an Animal-Assisted Intervention in Supporting Children Victims of Domestic Violence]. Master’s dissertation, Universidade Fernando Pessoa, Porto, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Sarman, Abdullah, and Ulviye Günay. 2023. The effects of goldfish on anxiety, fear, psychological and emotional well-being of hospitalized children: A randomized controlled study. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 68: e69–e78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signal, Tania, Nik Taylor, Kathy Prentice, Maria McDade, and Karena Jane Burke. 2017. Going to the dogs: A quasi-experimental assessment of animal assisted therapy for children who have experienced abuse. Applied Developmental Science 21: 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Sonia, Colleen Anne Dell, Tim Claypool, Darlene Chalmers, and Aliya Khalid. 2023. Case report: A community case study of the human-animal bond in animal-assisted therapy: The experiences of psychiatric prisoners with therapy dogs. Frontiers in Psychiatry 14: 1219305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spruin, Elizabeth, Katarina Mozova, Anke Franz, Susanna Mitchell, Ana Fernandez, Tammy Dempster, and Nicole Holt. 2019. The use of therapy dogs to support court users in the waiting room. International Criminal Justice Review 29: 284–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uglow, Lyndsey S. 2019. The benefits of an animal-assisted intervention service to patients and staff at a children’s hospital. British Journal of Nursing 28: 509–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Children’s Fund—UNICEF. 2017. A Familiar Face: Violence in the Lives of Children and Adolescents. New York: UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- Walden, Marlene, Austin Lovenstein, Amelia Randag, Sherry Pye, Brianna Shannon, Esther Pipkin, Amy Ramick, Keri Helmick, and Margaret Strickland. 2020. Methodological challenges encountered in a study of the impact of animal-assisted intervention in pediatric heart transplant patients. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 53: 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Objectives | Activity | Activity Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Establishing a Safe Environment | Feel to Know | Free interaction with the dog to identify areas of affection, followed by painting the “pampering guide” with colors associated with the dog’s emotions. |

| Both | Individual sessions with the dog focused on each child’s personal issues in a safe and private environment. | |

| 2. Promotion of Expression | Curious Dog | Dog delivers balls with questions inside, encouraging the child to express themselves verbally and emotionally. |

| Feel to Know | The activity also encourages emotional expression through painting associated with the dog’s feelings. | |

| 3. Development of Social Skills | Group of Very Special People | Children choose adjectives or pictures from the dog’s vest and offer them to another classmate, promoting recognition and empathy. |

| Search Game | Children hide objects and, together with the dog, search for the items, promoting cooperation and communication. | |

| Obstacle Course | Building and overcoming an obstacle course with the dog, working on collaboration and problem-solving. | |

| 4. Increased Self-Esteem | Double Training Circuit | Children guide the dog through different stations, reinforcing leadership, autonomy, and a sense of accomplishment. |

| What Do You Want to Teach? | Each child chooses and teaches the dog a skill, exercising responsibility and initiative. | |

| Presentation of Skills | Children present to the group what they taught the dog, promoting pride, validation, and self-esteem. |

| Code | Age | Marital Status | Nationality | Educational (Ed.) Level | Employment Situation | Shelter Stay Time | No. of Children | Children’s Age | Sex Children |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 34 | Married | Brazilian | Secondary education | Unemployed | 9 months | 2 | 6 and 6 | M and F |

| M2 | 37 | Single | Portuguese | Secondary education | Unemployed | 15 months | 1 | 8 | M |

| M3 | 24 | Single | Portuguese | 3rd cycle of basic Ed. | Unemployed | 9 months | 2 | 3 and 2 | M and F |

| M4 | 44 | Divorced | Brazilian | Secondary education | Unemployed | 2 months | 1 | 4 | M |

| M5 | 36 | Divorced | Portuguese | 3rd cycle of basic Ed. | Unemployed | 7 months | 2 | 2 and 11 | M and F |

| M6 | 48 | Married | Angolan | Secondary education | Employee | 3 months | 2 | 15 and 19 | F and F |

| Categories | Subcategories |

|---|---|

| A1. (Non) The existence of contact with a pet |

| A2. Bonding with the animal | |

| B1. Positive expectations |

| B2. Negative expectations | |

| C1. Description of dogs |

| C2. Activities | |

| C3. Behavior of child/ren | |

| C4. Participation of child/children | |

| D1. Changes in the child’s/children’s behavior |

| D2. Changes in relationships | |

| D3. Difficulties after the intervention | |

| D4. Animal-assisted intervention |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

da Silva Santos, I.; Sani, A.I. Mothers’ Perceptions of Interactions in Animal-Assisted Activities with Children Exposed to Domestic Violence in Shelters: A Qualitative Study. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060393

da Silva Santos I, Sani AI. Mothers’ Perceptions of Interactions in Animal-Assisted Activities with Children Exposed to Domestic Violence in Shelters: A Qualitative Study. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(6):393. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060393

Chicago/Turabian Styleda Silva Santos, Inês, and Ana Isabel Sani. 2025. "Mothers’ Perceptions of Interactions in Animal-Assisted Activities with Children Exposed to Domestic Violence in Shelters: A Qualitative Study" Social Sciences 14, no. 6: 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060393

APA Styleda Silva Santos, I., & Sani, A. I. (2025). Mothers’ Perceptions of Interactions in Animal-Assisted Activities with Children Exposed to Domestic Violence in Shelters: A Qualitative Study. Social Sciences, 14(6), 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060393