Changes in Aggressive Behaviors over Time in Children with Adverse Childhood Experiences: Focusing on the Role of School Connectedness

Abstract

1. Aggressive Behavior and Its Trajectory over Time

2. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Aggressive Behavior

3. Effects of School Connectedness on Aggressive Behaviors with the Social Development Model

4. The Current Study

5. Methods

5.1. Sample and Participants

5.2. Measures

5.2.1. Adverse Childhood Experiences

5.2.2. School Connectedness

5.2.3. Aggressive Behavior

5.2.4. Demographic Information

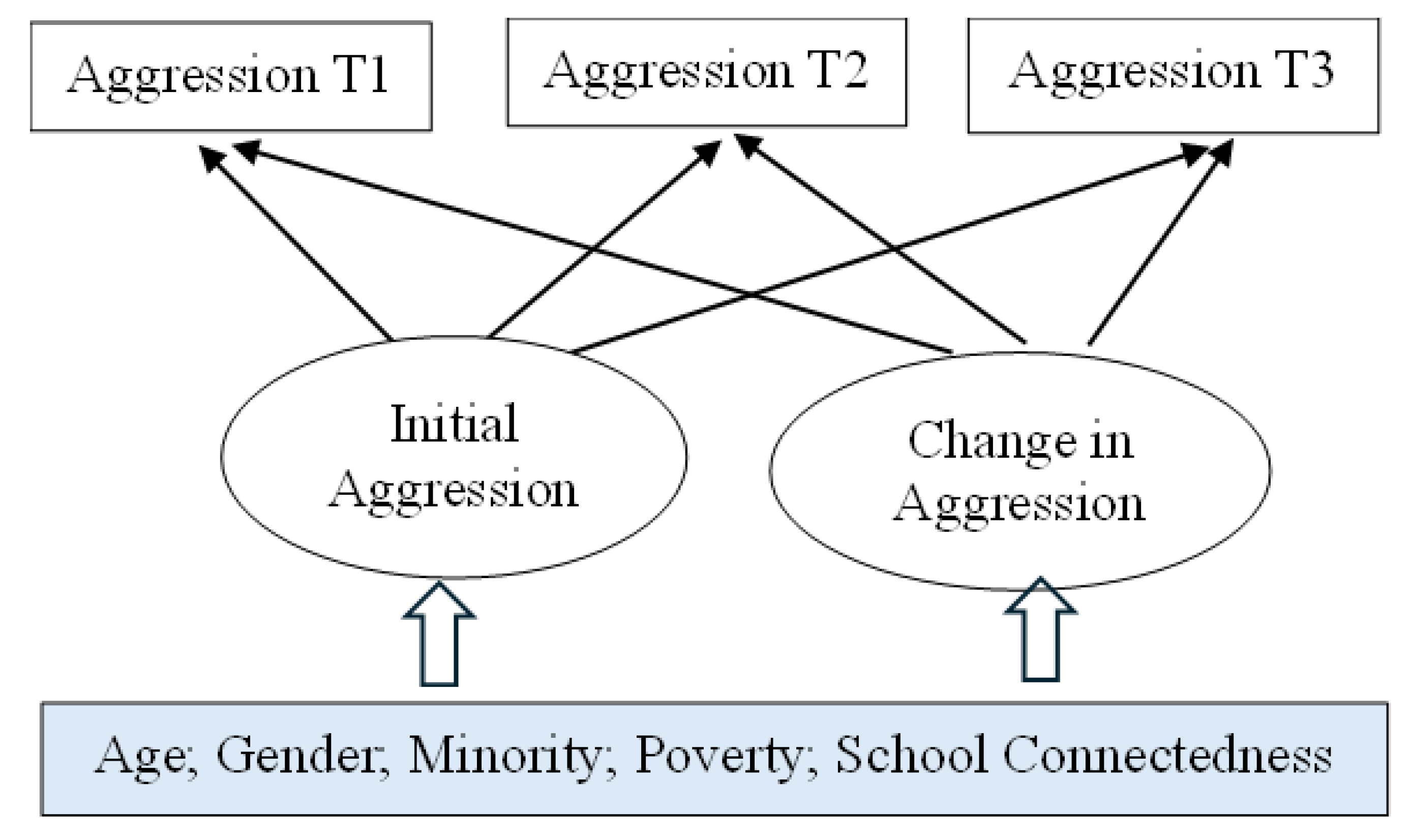

5.3. Analytic Plan

6. Results

7. Discussion

7.1. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

7.2. Practice Implications

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Achenbach, Thomas M. 1992. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/2-3 and 1992 Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Aquilar, Serena, Dario Bacchini, and Gaetana Affuso. 2018. Three-year cross-lagged relationships among adolescents’ antisocial behavior, personal values, and judgment of wrongness. Social Development 27: 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Brian. 2011. Childhood psychological abuse and adult aggression: The mediating role of self-capacities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 26: 2093–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aroyewum, Bushura Afolabi, Sunday Oladotun Adeyemo, and Divine Chioma Nnabuko. 2023. Aggressive behavior: Examining the psychological and demographic factors among university students in Nigeria. Cogent Psychology 10: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asscher, Jessica J., Claudia E. Van der Put, and Geert Jan J. M. Stams. 2015. Gender differences in the impact of abuse and neglect victimization on adolescent offending behavior. Journal of Family Violence 30: 215–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglivio, Michael T., Kevin T. Wolff, Matt DeLisi, Michael G. Vaughn, and Alex R. Piquero. 2016. Effortful control, negative emotionality, and juvenile recidivism: An empirical test of DeLisi and Vaughn’s temperament-based theory of antisocial behavior. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology 27: 376–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Erin R., and Cjersti J. Jensen. 2024. Linking teacher-versus child self-report discrepancies in aggression to demographic and cognitive profiles. Early Childhood Education Journal 52: 443–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Erin R., Cjersti J. Jensen, and Marie S. Tisak. 2019. A closer examination of aggressive subtypes in early childhood: Contributions of executive function and single-parent status. Early Child Development and Care 189: 733–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benish-Weisman, Maya. 2015. The interplay between values and aggression in adolescence: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology 51: 677–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benish-Weisman, Maya. 2019. What can we learn about aggression from what adolescents consider important in life? The contribution of values theory to aggression research. Child Development Perspectives 13: 260–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, Aprile D., Yijie Wang, Yishen Shen, Alaina E. Boyle, Richelle Polk, and Yen-Pi Cheng. 2018. Racial/ethnic discrimination and well-being during adolescence: A meta-analytic review. American Psychologist 73: 855–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, Lyndal, Helen Butler, Lyndal Thomas, John Carlin, Sara Glover, Glenn Bowes, and George Patton. 2007. Social and school connectedness in early secondary school as predictors of late teenage substance use, mental health, and academic outcomes. Journal of Adolescent Health 40: 357.e9–357.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bos, Marieke G. N., Lara M. Wierenga, Neeltje E. Blankenstein, Elisabeth Schreuders, Christian K. Tamnes, and Eveline A. Crone. 2018. Longitudinal structural brain development and externalizing behavior in adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 59: 1061–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broidy, Lisa M., Daniel S. Nagin, Richard E. Tremblay, John E. Bates, Bobby Brame, Kenneth A. Dodge, David Fergusson, John L. Horwood, Rolf Loeber, Robert Laird, and et al. 2003. Developmental trajectories of childhood disruptive behaviors and adolescent delinquency: A six-site, cross-national study. Developmental Psychology 39: 222–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, Robert T., Michael Y. Lau, Veronica Johnson, and Katherine Kirkinis. 2017. Racial discrimination and health outcomes among racial/ethnic minorities: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Multicultural Counseling & Development 45: 232–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, Richard F., Rick Kosterman, J. David Hawkins, Michael D. Newcomb, and Robert D. Abbott. 1996. Modeling the etiology of adolescent substance abuse: A test of the social development model. Journal of Drug Issues 26: 429–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/aces/index.html (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Choi, Mijin, Jun Sung Hong, Raphael Travis, Jr., and Jangmin Kim. 2022. Effects of school environment on depression among Black and White adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology 51: 1181–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Mijin, Sei-Young Lee, Jangmin Kim, and Jungup Lee. 2024. The interaction of race/ethnicity and school connectedness in presenting internalizing and externalizing behaviors among adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review 161: 107605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Yoonsun, Tracy W. Harachi, Mary Rogers Gillmore, and Richard F. Catalano. 2005. Applicability of the social development model to urban ethnic minority youth: Examining the relationship between external constraints, family socialization, and problem behaviors. Journal of Research on Adolescence 15: 505–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cleverly, Kristin, Peter Szatmari, Tracy Vaillancourt, Michael Boyle, and Ellen Lipman. 2012. Developmental trajectories of physical and indirect aggression from late childhood to adolescence: Sex differences and outcomes in emerging adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 51: 1037–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, Daniel F., Jennifer J. Anderson, Ronald J. Steingazd, and Julie A. Cunningham. 2004. Proactive and reactive aggression in referred children and adolescents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 74: 129–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosnoe, Robert, Kristan Glassgow Erickson, and Sanford M. Dornbusch. 2002. Protective function of family relationships and school factors on the deviant behavior of adolescent boys and girls: Reducing the impact of risky friendships. Youth & Society 33: 515–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLisi, Matt, and Eric Beauregard. 2018. Adverse childhood experiences and criminal extremity: New evidence for sexual homicide. Journal of Forensic Science 63: 484–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duggins, Shaun D., Gabriel P. Kuperminc, Christopher C. Henrich, Ciara Smalls-Glover, and Julia L. Perilla. 2016. Aggression among adolescent victims of school bullying: Protective roles of family and school connectedness. Psychology of Violence 6: 205–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duprey, Erinn Bernstein, Assaf Oshri, and Sihong Liu. 2020. Developmental pathways from child maltreatment to adolescent suicide-related behaviors: The internalizing and externalizing comorbidity hypothesis. Development and Psychopathology 32: 945–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltink, E. M. A., J. Ten Hoeve, T. De Jongh, G. H. P. Van der Helm, I. B. Wissink, and G. J. J. M. Stams. 2018. Stability and change of adolescents’ aggressive behavior in residential youth care. Child & Youth Care Forum 47: 199–217. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer, Emillo, Fumiaki Hamagami, and John J. McArdle. 2004. Modeling latent growth curves with incomplete data using different types of structural equation modeling and multilevel software. Structural Equation Modeling 11: 452–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fite, Paula J., Craig R. Colder, and John E. Lochman. 2008. The Relation between childhood proactive and reactive aggression and substance use initiation. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 36: 261–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fite, Paula J., Craig R. Colder, John E. Lochman, and Karen C. Wells. 2007. Pathways from proactive and reactive aggression to substance use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 21: 355–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, Patrick J., Carolyn J. Tompsett, Jordan M. Braciszewski, Angela J. Jacques-Tiura, and Boris B. Baltes. 2009. Community violence: A meta-analysis on the effect of exposure and mental health outcomes of children and adolescents. Development and Psychopathology 21: 227–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, Adrian, and Lenna Nepomnyaschy. 2024. School connectedness and mental health among black adolescents. Journal of Youth & Adolescence 53: 1066–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilligan, Robbie. 2004. Promoting resilience in child and family social work. Social Work Education 23: 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greeson, Johanna K. P., Ernestine C. Briggs, Christopher M. Layne, Harolyn M. E. Belcher, Sarah A. Ostrowski, Soeun Kim, Robert C. Lee, Rebecca L. Vivrette, Robert S. Pynoos, and John A. Fairbank. 2013. Traumatic Childhood Experiences in the 21st Century: Broadening and Building on the ACE Studies with Data From the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 29: 536–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammen, Constance, Risha Henry, and Shannon E. Daley. 2000. Depression and sensitization to stressors among young women as a function of childhood adversity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 68: 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, Dale F., Amy L. Paine, Oliver Perra, Kaye V. Cook, Salim Hashmi, Charlotte Robinson, Victoria Kairis, and Rhiannon Slade. 2021. Prosocial and aggressive behavior: A longitudinal study. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 86: 7–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschi, Travis. 2002. Causes of Delinquency. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, David. 2009. A Brief Introduction to Social Work Theory. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, Rex B. 1998. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kokko, Katja, and Lea Pulkkinen. 2000. Aggression in childhood and long-term unemployment in adulthood: A cycle of maladaptation and some protective factors. Developmental Psychology 36: 463–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeDoux, Joseph E., and Daniel S. Pine. 2016. Using Neuroscience to Help Understand Fear and Anxiety: A Two-System Framework. American Journal Of Psychiatry 173: 1083–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Sei-Young, Margarita Villagrana, and Aweke Tadesse. 2020. Gender-specific Trajectories of Maltreatment, School Engagement, and Delinquency: The Protective Role of School Engagement. Victims & Offenders 16: 587–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Sei-Young, Siyon Rhee, and Margarita Villagrana. 2018. Change in delinquency over time between adolescents with and without maltreatment experiences: Attachment and the school’s role. Children and Youth Services Review 86: 110–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loehlin, John C. 1992. Latent Variable Models: An Introduction to Factor, Path, and Structural Analysis, 2nd ed. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura, Naomi, Toshiaki Hashimoto, and Motomi Toichi. 2013. Associations among adverse childhood experiences, aggression, depression, and self-esteem in serious female juvenile offenders in Japan. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology 24: 111–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, Elizabeth M., Laura Stoppelbein, Sarah E. O’Kelley, Paula Fite, and Shana B. Smith. 2021. An examination of post-traumatic stress symptoms and aggression among children with a history of adverse childhood experiences. Journal of Psychopathology & Behavioral Assessment 43: 657–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, Angela J., Luisa M. Rivera, Rosemary E. Bernstein, William W. Harris, and Alicia F. Lieberman. 2018. Positive childhood experiences predict less psychopathology and stress in pregnant women with childhood adversity: A pilot study of the benevolent childhood experiences (BCEs) scale. Child Abuse and Neglect 78: 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, Kelly E., Terri N. Sullivan, Katherine M. Ross, and Khiya J. Marshall. 2021. “Hurt people hurt people”: Relations between adverse experiences and patterns of cyber and in-person aggression and victimization among urban adolescents. Aggressive Behavior 47: 483–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oei, Adam, Dongdong Li, Chi Meng Chu, Irene Ng, Eric Hoo, and Kala Ruby. 2023. Disruptive behaviors, antisocial attitudes, and aggression in young offenders: Comparison of Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) typologies. Child Abuse & Neglect 141: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardini, Dustin A., Adrian Raine, Kirk Erickson, and Rolf Loeber. 2014. Lower amygdala volume in men is associated with childhood aggression, early psychopathic traits, and future violence. Biological Psychiatry 75: 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piquero, Alex R., Michael L. Carriaga, Brie Diamond, Lila Kazemian, and David P. Farrington. 2012. Stability in aggression revisited. Aggression and Violent Behavior 17: 365–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichman, Nancy E., Julien O. Teitler, Irwin Garfinkel, and Sara S. McLanahan. 2001. Fragile families: Sample and design. Children and Youth Services Review 23: 303–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Hannah, Elena Pozzi, Nandita Vijayakumar, Sally Richmond, Katherine Bray, Camille Deane, and Sarah Whittle. 2021. Structural Brain Development and Aggression: A Longitudinal Study in Late Childhood. Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience 21: 401–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabella, Kathryn, Ian A. Lane, Murron O’Neill, and Natalie Tincknell. 2024. Young adults’ perceptions of adverse childhood experiences as context and causes of mental health conditions: Observations from the United States. Child Protection and Practice 3: 100067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, Margaret A., and Katie A. McLaughlin. 2014. Dimensions of early experience and neural development: Deprivation and threat. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 18: 580–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Jihee. 2023. Patterns of Adverse Childhood Experiences and Psychiatric Disorders Among Adolescents with ADHD: A Latent Class Analysis. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoppelbein, Laura, Elizabeth McRae, and Shana Smith. 2024. Exploring the nexus of adverse childhood experiences and aggression in children and adolescents: A scoping review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 25: 3346–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus, Murray A., Sherry L. Hamby, David Finkelhor, Ddavid W. Moore, and Desmond Runyan. 1998. Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent–Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse and Neglect 22: 249–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedo, Elizabeth A., Sanjana Pampati, Kayla N. Anderson, Evelyn Thorne, Izraelle I. McKinnon, Nancy D. Brener, Joi Stinson, Jonetta J. Mpofu, and Phyllis Holditch Niolon. 2024. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Health Conditions and Risk Behaviors Among High School Students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2023. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 73: 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Yunlong, Chengfu Yu, Shuang Lin, Junming Lu, Yi Liu, and Wei Zhang. 2019. Parental psychological control and adolescent aggressive behavior: Deviant peer affiliation as a mediator and school connectedness as a moderator. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The U.S. Census. 2023. Fact Check. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/RHI825223 (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- van den Heuvel, Leigh Luella, Ayesha Assim, Milo Koning, Jani Nöthling, and Soraya Seedat. 2025. Childhood maltreatment and internalizing/externalizing disorders in trauma-exposed adolescents: Does posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) severity have a mediating role? Development and Psychopathology 37: 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yao, Haksoon Ahn, Roderick A. Rose, and Kimberly Williams. 2023. Effects of school connectedness on the relationship between child maltreatment and child aggressive behavior: A mediation analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect 136: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, Kaitlin P., Andrew C. Grogan-Kaylor, Julie Ma, Garrett T. Pace, Shawna. J. Lee, and Pamela. E. Davis-Kean. 2025. Interactions of gender inequality and parental discipline predicting child aggression in low- and middle-income countries. Child Development 96: 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

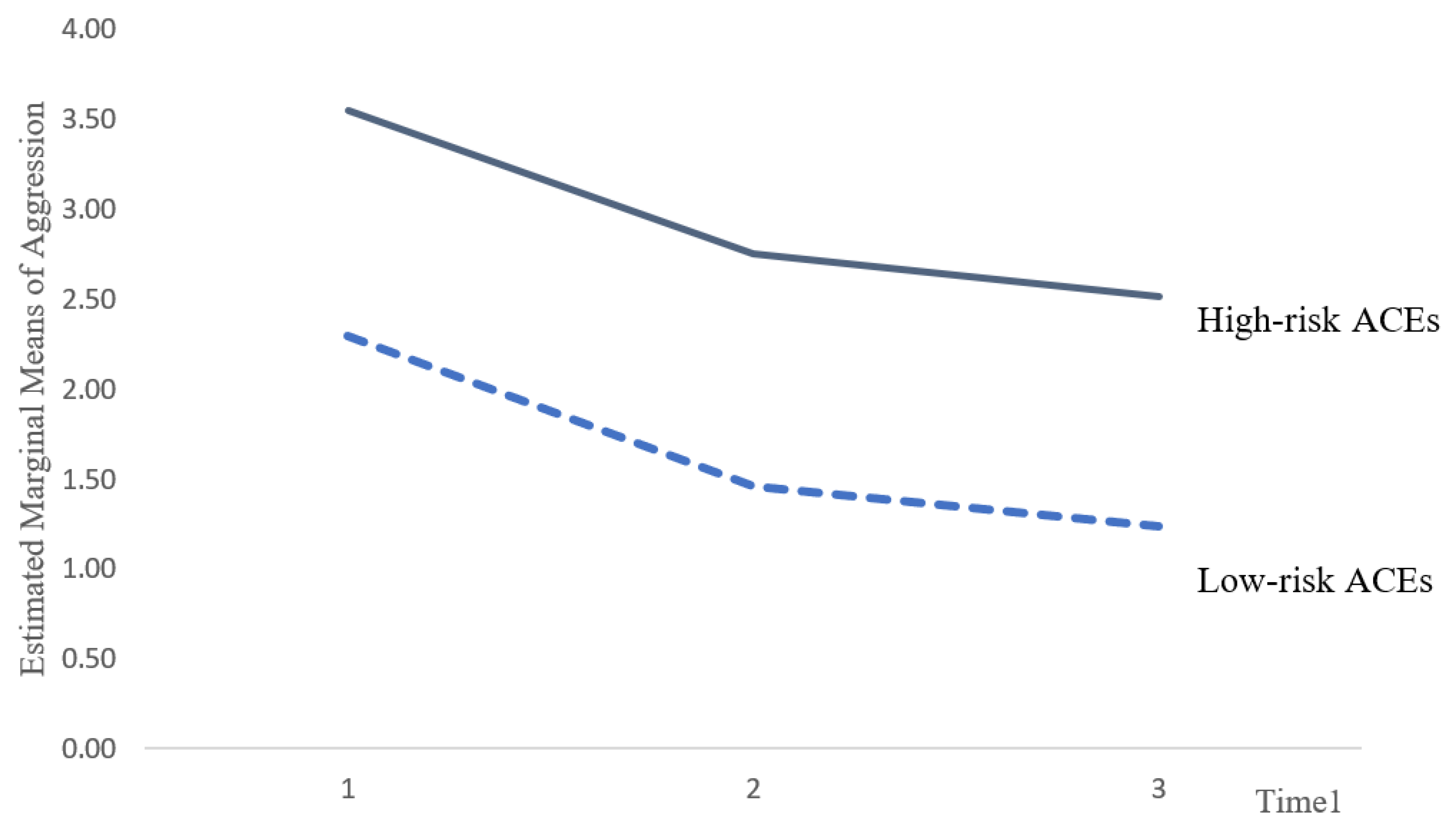

| Time Effect | Group Effect | Interaction Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aggressive Behavior | F (1, 2233) = 323.65 *** | F (1, 2233) = 289.03 *** | F(1, 2233) = 0.07 |

| Low-Risk ACEs | High-Risk ACEs | All | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2/df | CFI | RMSEA | χ2/df | CFI | RMSEA | χ2/df | CFI | RMSEA | |

| Aggressive Behavior | |||||||||

| No change | 20.37/2 *** | 0.99 | 0.056 | 10.26/2 * | 0.99 | 0.056 | 16.85/2 *** | 0.99 | 0.042 |

| Linear change | 739.65/2 *** | 0.47 | 0.355 | 50.11/2 *** | 0.94 | 0.136 | 512.82/2 *** | 0.808 | 0.16 |

| Non-Linear change | 26.01/2 *** | 0.96 | 0.092 | 2.85/2 | 0.99 | 0.018 | 15.37/2 *** | 0.98 | 0.058 |

| Low-Risk ACEs | High-Risk ACEs | All | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | |||

| Mean | 2.38 (0.31) *** | 3.53 (0.07) *** | 2.74 (0.03) *** |

| Variance | 1.15 (0.05) *** | 2.94 (0.18) *** | 1.99 (0.07) *** |

| Slope | |||

| Mean | −1.89 (0.06) *** | −1.81 (0.14) *** | −1.87 (0.06) *** |

| Variance | 0.18 (0.19) | 2.19 (0.72) ** | 0.86 (0.25) *** |

| χ2/df | 26.01 | 1.43 | 15.37 |

| CFI | 0.964 | 0.999 | 0.989 |

| RMSEA | 0.092 | 0.018 | 0.058 |

| Low-Risk ACEs | High-Risk ACEs | All | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggressive Behavior | Aggressive Behavior | Aggressive Behavior | ||||

| Intercept | Slope | Intercept | Slope | Intercept | Slope | |

| Age | −0.00 (0.06) | −0.11 (0.14) | −0.04 (0.11) | 0.04 (0.35) | −0.04 (0.05) | −0.02 (0.14) |

| Gender | 0.10 (0.06) *** | −0.10 (0.20) | 0.13 (0.15) ** | 0.08 (0.46) | 0.12 (0.06) *** | 0.08 (0.19) |

| Minority | 0.00 (0.09) | −0.12(0.29) | −0.05 (0.22) | 0.13 (0.68) | −0.00 (0.09) | 0.02 (0.29) |

| Poverty | −0.06 (0.09) | −0.35 (0.28) | −0.07 (0.16) | 0.05 (0.52) | −0.09 (0.08) ** | −0.08 (0.25) |

| School Connect | −0.13 (0.02) *** | −0.34 (0.05) * | −0.09 (0.03) * | −0.25 (0.10) * | −0.14 (0.02) *** | −0.24 (0.05) ** |

| Model Fit Statistics | χ2/df = 7.72 ***, CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.05 | χ2/df = 3.79 ***, CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.04 | χ2/df = 9.38 ***, CFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.04 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.-Y.; Choi, M. Changes in Aggressive Behaviors over Time in Children with Adverse Childhood Experiences: Focusing on the Role of School Connectedness. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060385

Lee S-Y, Choi M. Changes in Aggressive Behaviors over Time in Children with Adverse Childhood Experiences: Focusing on the Role of School Connectedness. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(6):385. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060385

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Sei-Young, and Mijin Choi. 2025. "Changes in Aggressive Behaviors over Time in Children with Adverse Childhood Experiences: Focusing on the Role of School Connectedness" Social Sciences 14, no. 6: 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060385

APA StyleLee, S.-Y., & Choi, M. (2025). Changes in Aggressive Behaviors over Time in Children with Adverse Childhood Experiences: Focusing on the Role of School Connectedness. Social Sciences, 14(6), 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060385