Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Policies: Addressing Unintended Effects on Inequalities

Abstract

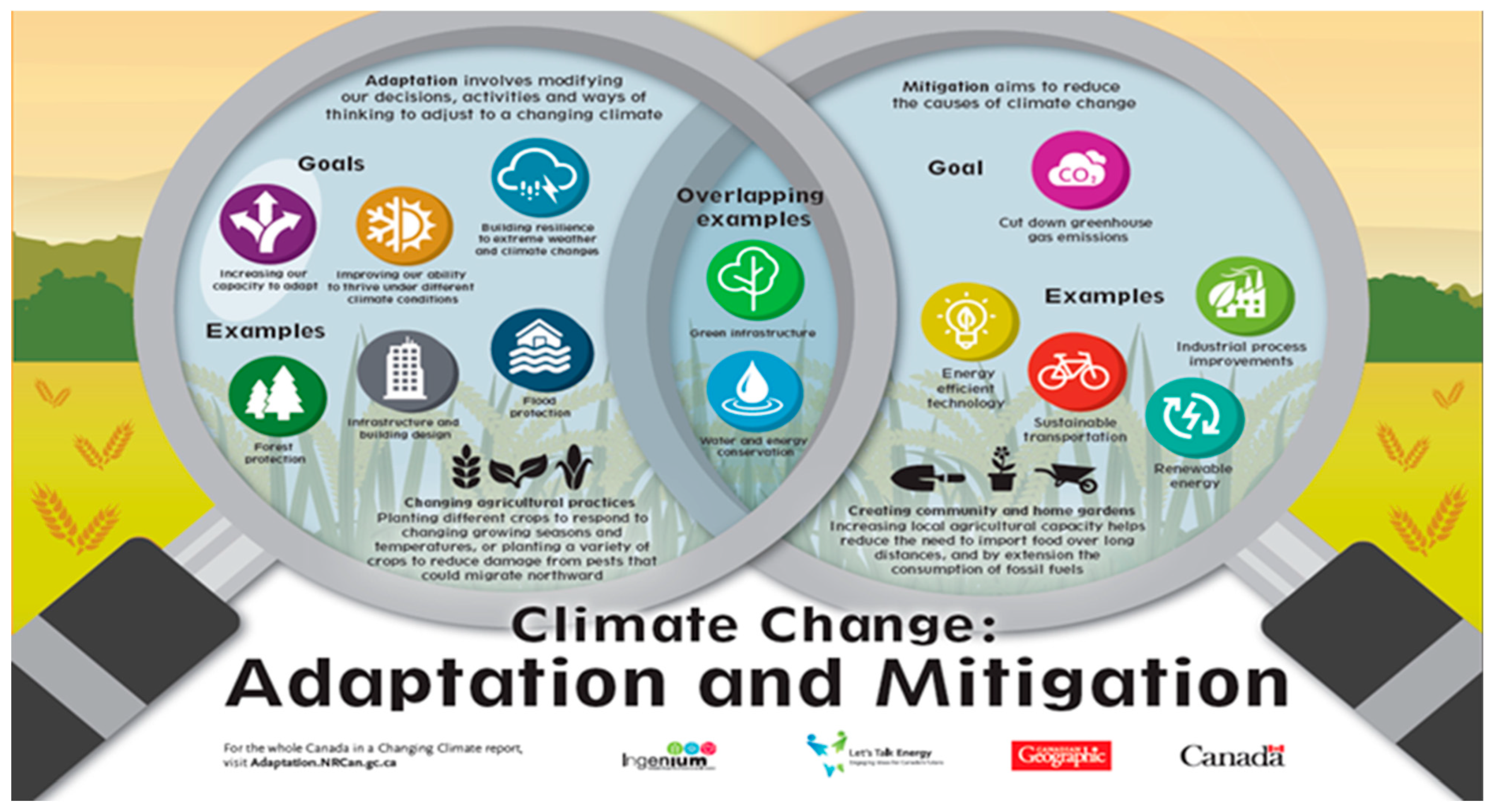

1. Introduction: Inequality and Climate Change

Climate change exacerbates inequality…

… and inequalities exacerbate climate change

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results: Unintended Effects of Climate Policies on the Most Vulnerable

3.1. Adaptation Policies and Measures and Vulnerable People

“When faced with the immediate needs of their families, they must take down trees for a quick profit. Some people will harvest trees to turn into charcoal to quickly earn cash. In other places, forest areas are cleared and burned to be used as extra land for farming. Eventually, these areas lose so many trees that soil and water are left unprotected”.(PwP 2018)

“EWSs have traditionally focused on technology and infrastructure with the absence of comprehensive engagement with the community across the four EWS elements of risk knowledge, monitoring, dissemination and communication and response capability. Subsequently, past experience shows inappropriate responses by communities during disasters”.

- Challenges in the identification of disadvantaged people, even for those who are cognisant of the discourse surrounding intersectionality. Frequently, this awareness is not accompanied by the ability to accurately identify and map the various categories of vulnerable individuals within the designated territory.

- Poor availability of preparedness measures for vulnerable groups (preparedness measures are often conceived without taking into account the enormous differences within the human groups that inhabit a territory, even in the best cases where the specific context has been carefully considered).

- Inadequate coordination between actors (there are many diverse actors involved in improving community preparedness, including public and non-profit organisations that have expertise in a particular type of vulnerability—e.g., those caring for children or the elderly; the disabled; or migrants—and it is very difficult to ensure adequate coordination between them).

- Lack of policies and plans to promote preparedness among vulnerable groups (also because of the above, there is a lack of tailor-made measures for specific groups of people; therefore, plans and policies, even when they address these issues, are often generic).

- Lack of trust (of vulnerable people) towards stakeholders due to negative experiences in the past, also because their specificities have not been taken into account in the past, if at all, and therefore many people believe that policies are leaving them behind and will leave them behind).

“Farmers were shifting from traditional farming practices to more ecosystem-based, integrated farming practices that are less climate-sensitive. Combined agriculture, selecting drought-tolerant rice varieties, and shifting cropping patterns were some strategies that farmers adopted to address risks”.

3.2. Mitigation Policies and Measures and Vulnerable People

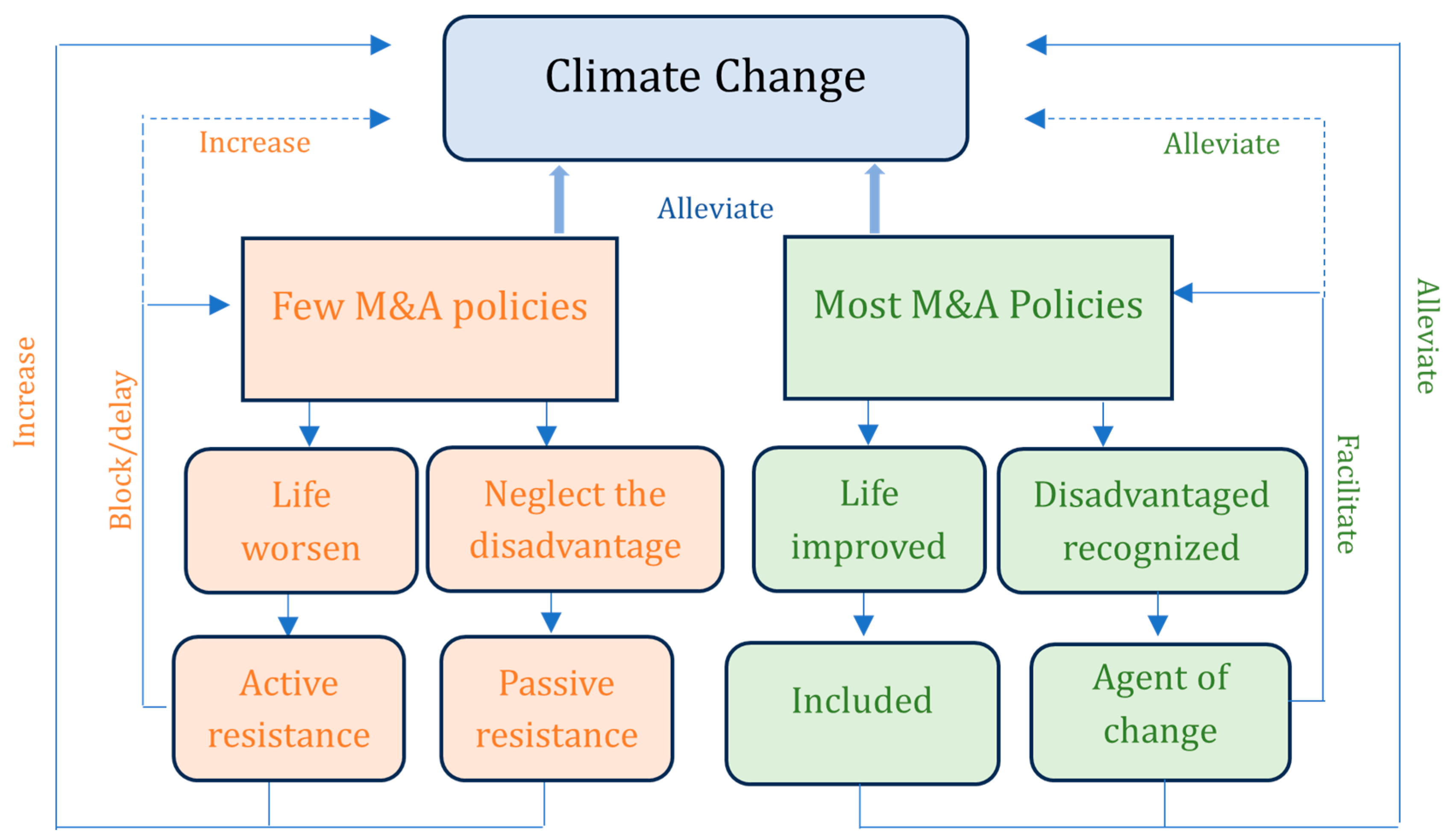

4. Discussion: An Uncertain and Precarious Situation

4.1. Resistances

“… is that it is essential to recognise resistance as a legitimate, complex response to work with, rather than as a hurdle to overcome. By acknowledging and working with resistance, policymakers can uncover gaps in inclusivity, barriers to access or mistrust stemming from marginalisation. This recognition can foster constructive dialogue and result in policies rooted in equality and justice”.

4.2. Disadvantaged People as Agents of Change for Climate Action

4.3. Combine Climate Justice and Social Justice

“Climate justice connects the climate crisis to social, racial, and environmental issues, recognizing the disproportionate impacts of climate change on low-income people (…). It acknowledges that not everyone has contributed equally to climate change and aims to combat social, gender, economic, intergenerational, and environmental injustices (…). This entails ensuring representation, inclusion, and protection of the rights of those most vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Solutions must promote equity, assure access to basic resources”.

“Climate justice has become prominent in academia, policy circles, and among climate activists, but the notion of justice is highly subjective, and climate justice is often invoked without a clear definition of the concept. To achieve climate justice, it is necessary to clarify what it means in specific contexts (…). Climate justice is social justice in the Global South”.

- There is still a certain conceptual or even terminological confusion on the issue (as is illustrated by the tension between the notions of social and climate justice);

- There is, however, a certain sensitivity on the part of some representatives of both the scientific community and the community of practitioners (e.g., international organisations) to the effective inclusion of social justice issues in the design and implementation of policies related to climate change;

- Nevertheless, on the one hand, this awareness is still limited and, on the other hand, the combination of all this is very complex and there do not seem to be any already elaborated and validated schemes on how to proceed;

- Finally, the empirical situations to refer to are very diverse, so, it is not surprising to find, so far, a limited impact on mitigation and adaptation policies (see Section 3).

4.4. Identifying Some Policy Recommendations

“There is a tendency in the public debate on climate change to present the use and development of green technologies as a miracle solution or panacea. We often forget one aspect: it is crucial to ensure that their development goes hand in hand with social justice (…). Without equality and equity—in other words, without peace and security—we cannot effectively fight climate change”.

- Make agendas (from policymakers to NGOs) inclusive so that inequalities become more visible, and the organisation can generate egalitarian/just/inclusive policy alternatives.

- Encouraging administrations in charge of climate change challenges to share targeted resources ensures that local (vulnerable) groups receive the necessary support.

- Promoting a local approach where policymakers and scientists team up with citizens that rarely get a voice can be a game changer. Actively monitoring and understanding the local impacts of climate change can be a starting point for further action. The on-ground understanding can be a trigger for action, e.g., to mitigate risks, improve disaster response, or increase the adaptive capacity of communities in view of the climate-change related crisis.

- Recognising and celebrating positive stories and initiatives to inspire replication and highlight the success and impact of local community-led efforts. By acknowledging and sharing success stories, we inspire and motivate others to engage in similar initiatives, fostering a culture of innovation and resilience.

- Employing various tools for facilitation, conflict resolution, and dialogue-building to navigate the processes being slowed down by resistance, and to encourage the voluntary inclusion of marginalised groups.

- Identifying hotspots where sustainability transitions and transformations are likely to lead to tensions between social and environmental concerns. Pre-existing axes of inequality often shape vulnerability and disadvantage. Insights gained from resistance can contribute to long-term solutions to complex matters such as human rights and social equity, cultural heritage protection, and safety from natural hazards.

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | weADAPT is an online ‘open space’ on climate adaptation issues (including the synergies between adaptation and mitigation), which allows practitioners, researchers, and policymakers to access information and to share experiences and lessons learnt with the weADAPT community. |

| 2 | The majority of people characterised by vulnerability profiles do not see themselves as vulnerable and tend to reject the label. For this reason, we prefer to speak of people living in disadvantaged conditions (see ACCTING). However, the terms ‘vulnerable’ and ‘vulnerability’ are widely used in the literature, so we cannot help but make extensive use of them. |

| 3 | An example is the Superbonus 110% established in Italy. It consisted of a 110% deduction of expenses incurred from 1 July 2020 to 31 December 2023 for the implementation of specific interventions aimed, among others, at energy efficiency and the installation of photovoltaic systems (see https://www.agenziaentrate.gov.it/portale/superbonus-110%25#:~:text=Interventi%20principali (accessed on 18 September 2024). Since public finances actually cover 110% of the costs, it would seem accessible to everyone. In reality, all buildings where there is any construction abuse or any other type of anomaly that can date back to several decades before are excluded. This is a very common situation in Italy in houses built in past decades and almost all people living in disadvantaged conditions live there (Accetturo et al. 2024). |

| 4 | For more information, see also https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/funding/just-transition-fund_en (accessed on 8 April 2025); https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/finance-and-green-deal/just-transition-mechanism_en (accessed on 13 March 2025); https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/green-deal-industrial-plan_en (accessed on 13 March 2025); https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/finance-and-green-deal/just-transition-mechanism/just-transition-funding-sources_en (accessed on 13 March 2025). |

References

- ACCESS. 2024. Fuel Poverty—What Is It and How Can It Be Tackled? Available online: https://www.theaccessgroup.com/en-gb/blog/hsc-fuel-poverty-what-is-it-and-how-can-it-be-tackled/ (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Accetturo, Antonio, Elisabetta Olivieri, and Fabrizio Renzi. 2024. Incentives for Dwelling Renovations: Evidence from a Large Fiscal Programme. No. 860. Rome: Bank of Italy, Economic Research and International Relations Area. Available online: https://www.bancaditalia.it/pubblicazioni/qef/2024-0860/QEF_860_24.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Adger, W. Neil, Shardul Agrawala, M. Monirul Qader Mirza, Cecilia Conde, Karen O’Brien, Juan Pulhin, Roger Pulwarty, Barry Smit, and Kiyoshi Takahashi. 2007. Assessment of adaptation practices, options, constraints and capacity. In Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Edited by Martin Parry, Osvaldo Canziani, Jean Palutikof, Paul van der Linden and Claire Hanson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 717–43. [Google Scholar]

- Allwood, Gill. 2020. Mainstreaming gender and climate change to achieve a just transition to a climate-neutral Europe. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 58: 173–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria. 2010. Déferlement de 50 millions de m3 d’eau au barrage du Vajont. fiche N° 23607. Paris: Ministère du développement durable (French Ministry of Sustainable Development)—DGPR/SRT/BARPI. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, Hilary, and Lisa O’Malley. 2005. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldelli, Madeline, Marina Mattera, and Florence Renou-Wilson. 2025. From Awareness to Action: A Study of Capacity-Building Engagement Techniques for Fostering Climate-Adaptive Behaviours in Citizens. European Journal of Education 60: e70056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, Luis. 2024. What Determines A Disaster? 54 Pesos. [Google Scholar]

- Bellagamba, Corrado. 2023. L’identikit di chi compra l’auto elettrica (The Identikit of Those Who Buy an Electric Car). Moveo by TelePass. Available online: https://moveo.telepass.com/lidentikit-di-chi-compra-auto-elettrica/#:~:text=L’acquirente%20tipo%20viene%20dal,di%20un%20gruppo%20di%20acquisto (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Bellarby, Jessica, Reyes Tirado, Adrian Leip, Franz Weiss, Jan Peter Lesschen, and Pete Smith. 2013. Livestock greenhouse gas emissions and mitigation potential in Europe. Global Change Biology 19: 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berriane, Yasmine, and Marie Duboc. 2020. Allying beyond social divides: An introduction to contentious politics and coalitions in the Middle East and North Africa. In Allying Beyond Social Divides. London: Routledge, pp. 1–21. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/13629395.2019.1639022 (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Boostani, Pariman, Giuseppe Pellegrini-Masini, and Gabriele Quinti. 2024. Report on Research Line 3: Leveraging Behavioural Change for Inclusive Energy Communities. ACCTING Project. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/15525880 (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Botzen, W. J. Wouter, Olivier Deschenes, and Mark Sanders. 2019. The economic impacts of natural disasters: A review of models and empirical studies. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy 13: 167–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breil, Margaretha, Clare Downing, Aleksandra Kazmierczak, Kirsi Mäkinen, and Linda Romanovska. 2018. Social Vulnerability to Climate Change in European Cities: State of Play in Policy and Practice. Bologna: European Topic Centre on Climate Change impacts, Vulnerability and Adaptation (ETC/CCA). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, Ebba, Ana Maria Vargas Falla, and Emily Boyd. 2023. Weapons of the vulnerable? A review of popular resistance to climate adaptation. Global Environmental Change 80: 102656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiati, Giovanni, Gabriele Quinti, Claudia Bassano, and Paolo Deiana. 2022. D3.6 Sulcis Case Study Report. ENTRANCES Project. Available online: https://entrancesproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/D3.6-Sulcis-Case-Study-Report.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Carmo, Renato Miguel. 2021. Social inequalities: Theories, concepts and problematics. SN Social Sciences 1: 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassandro, Martino. 2020. Animal breeding and climate change, mitigation and adaptation. Journal of Animal Breeding & Genetics 137: 121–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattani, Antonio David. 2007. Desigualdades socioeconômicas: Conceitos e problemas de pesquisa (Socioeconomic inequalities: Concepts and research problems). Sociologias 3: 74–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate-ADAPT. 2021. Adaptation in EU Policy Sectors. Copenhagen and Brussels: Climate-ADAPT. Available online: https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu/en/eu-adaptation-policy/sector-policies (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Climate-ADAPT. 2024. Preventive Relocation of Households at High Hydrogeological Risk in Piemonte. Copenhagen and Brussels: Climate-ADAPT. Available online: https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu/en/metadata/case-studies/preventive-relocation-of-households-at-high-hydrogeological-risk-in-piemonte-italy (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Colon, Cristina. 2022. What Is Climate Justice? And What Can We Do Achieve It? Florence: UNICEF. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/innocenti/stories/what-climate-justice-and-what-can-we-do-achieve-it (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- CREWS. 2016. CREWS Operational Procedures Note No 1 Programming and Project Development. Geneva: WMO Official. Available online: https://wmo.int/sites/default/files/2023-07/Revised_Operational_Procedures_Note_No1_Programming_and_Project_Development.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Declich, Andrea, Gabriele M. Quinti, and Paolo Signore. 2020. Assessment of Nontechnical Barriers. Deliverable 2.2 INNOVEAS Project. Available online: https://innoveas.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/INNOVEAS_WP2_State-of-the-art-needs-and-barriers-assessmentD2.2-Assessment-of-non-technical-barriers.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Dente, Bruno. 1992. Le Politiche Pubbliche in Italia. Bologna: Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Energy Security & Net Zero. 2023. Annual Fuel Poverty Statistics in England. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/63fcdcaa8fa8f527fe30db41/annual-fuel-poverty-statistics-lilee-report-2023-2022-data.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Duzel, Esin, Burcu Borhan Türeli, Marina Cacace, Sofia Strid, and Carolin Zorell. 2025. ACCTING Factsheet: Transformative resistance for a just and inclusive European Green Deal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC-European Commission. 2021. A Multidimensional Inequality Monitoring Framework for the European Union. Brussels: European Union Official. Available online: https://composite-indicators.jrc.ec.europa.eu/multidimensional-inequality (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- EC-European Commission. 2023. Climate Change? It’s the Fault of Production Practices, Not Just the Cows. CORDIS. Brussels: European Union Official. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/article/id/32504-climate-change-blame-it-on-production-practices-not-just-cows (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- EDP. 2024. Fighting Energy Poverty. Key Strategies. EDP: Available online: https://www.edp.com/en/media/edp-stories/fighting-energy-poverty-key-strategies (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- EEA-European Environmental Agency. 2024. Environmental Inequalities. Copenhagen: Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/topics/in-depth/environmental-inequalities (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- European Parliament. 2023a. Regulation (EU) 2023/955 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 May 2023 Establishing a Social Climate Fund and Amending Regulation (EU) 2021/1060. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2023.130.01.0001.01.ENG (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- European Parliament. 2023b. Support Schemes for Energy Audits and Energy Management Systems as Required by Art. 8/2 of the Energy Efficiency Directive (2012/27/EU). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2023/1791/oj (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Fabrizio, Stefania, Florence Jaumotte, and Marina Travares. 2024. Why Women Risk Losing Out in Shift to Green Jobs. Washington, DC: IMF Website Blog. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2024/10/07/why-women-risk-losing-out-in-shift-to-green-jobs (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Filčák, Richard, Daniel Škobla, Dušana Dokupilová, Matúš Grežo, Tomáš Jeck, and Branislav Uhrecký. 2022. D3.7 Horná Nitra Case Study Report. ENTRANCES Project. Available online: https://entrancesproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/D3.7-HORNA-NITRA-Case-Study-Report.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Gajdusek, Martin Felix, Esin Düzel, Burcu Borhan Türeli, Carina Green, Carolin Zorell, Ayşe Gül Altınay, and Gábor Szüdi. 2025. Valuing indigenous and local knowledge in disaster management and nature protection. ACCTING Factsheet. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/10490494 (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Galland, Olivier, and Yannick Lemel. 2018. Sociologie des Inégalités. Paris: Armand Colin. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannon, Kate. 2022. Women Entrepreneurs in Climate Change Adaptation. WECCA Project. Available online: https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/women-entrepreneurs-in-climate-change-adaptation/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Groasis. n.d. Avoid Natural Disasters by Planting Trees. Groasis Website. Available online: https://www.groasis.com/en/planting/how-to-prevent-natural-disasters (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Guivarch, Céline, Nicolas Taconet, and Aurélie Méjean. 2021. Linking Climate and Inequality; Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2021/09/climate-change-and-inequality-guivarch-mejean-taconet (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Hankivsky, Olena, Daniel Grace, Gemma Hunting, Melissa Giesbrecht, Alycia Fridkin, Sarah Rudrum, Olivier Ferlatte, and Natalie Clark. 2014. An intersectionality-based policy analysis framework: Critical reflections on a methodology for advancing equity. International Journal for Equity in Health 13: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heffron, Raphael J., and Darren McCauley. 2022. The ‘just transition’ threat to our Energy and Climate 2030 targets. Energy Policy 165: 112949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyen, Dirk Arne. 2023. Social justice in the context of climate policy: Systematizing the variety of inequality dimensions, social impacts, and justice principles. Climate Policy 23: 539–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. 2023. Global EV Outlook 2023—Executive Summary. Paris: IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2023/executive-summary (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- IFRC. 2009. World Disasters Report 2009. Focus on Early Warning, Early Action. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/world-disasters-report-2009-focus-early-warning-early-action (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- IFRC, and CREWS. 2021. People Centered Early Warning Systems: Learning from National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Geneva: IFRC Official. Available online: https://www.ifrc.org/document/people-centred-early-warning-systems (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- IPCC. 2014. Climate Change 2014 Synthesis Report. Geneva: IPCC, pp. 1059–72. Available online: https://greenunivers.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Synth%C3%A8se-Rapport-Giec.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- IPCC. 2023. AR6 Synthesis Report. Climate Change 2023. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-cycle/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Jayaraman, Thiagarajan. 2019. Climate and Social Justice. UNESCO Courier. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000370327_eng (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Jordan, Joanne Catherine, Raashee Abhilashi, and Anjum Shaheen. 2021. Gender-Sensitive Social Protection in the Face of Climate Risk. A Study in Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Madhya Pradesh, India. Available online: https://socialprotection.org/sites/default/files/publications_files/Jordan%20et%20al.%20%282021%29_INDIA.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Komorowska, Aleksandra, Wit Hubert, Wojciech Kowalik, and Ryszard Uberman. 2022. D3.1 Silesia Region Case Study Report. ENTRANCES Project. Available online: https://entrancesproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/D3.1-Silesia-Case-Study-Report.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Levy, Barry S., and Jonathan A. Patz. 2015. Climate change, human rights, and social justice. Annals of Global Health 81: 310–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LEXICO. 2021. English Dictionary. Oxford. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20210118111731/https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/vulnerability (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Liao, Weijun, Ying Fan, and Chunan Wang. 2023. Exploring the equity in allocating carbon offsetting responsibility for international aviation. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 114: 103566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipari, Francesca, Lara Lázaro-Touza, Gonzalo Escribano, Ángel Sánchez, and Alberto Antonioni. 2024. When the design of climate policy meets public acceptance: An adaptive multiplex network model. Ecological Economics 217: 108084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascia, Rosario. 2024. Auto Inquinanti ai Paesi Poveri. L’esportazione Irresponsabile (Polluting Cars to Poor Countries. Irresponsible Export). Natura Magazine. Available online: https://www.innatura.info/auto-inquinanti/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Mezzana, Daniele, and Gabriele Quinti. 2024. Voices from the Field. Volta Flood and Drought Management Program. Available online: https://www.floodmanagement.info/floodmanagement/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Voices-from-the-field_VFDM-26-06-2024.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Mirianna, Budimir, Šakić Trogrlić Robert, Almeida Cinthia, Arestegui Miguel, Chuquisengo Vásquez Orlando, Cisneros Abel, Cuba Iriarte Monica, Adama Dia, Leon Lizon, Giorgio Madueño, and et al. 2025. Opportunities and Challenges for People-Centred Multi-Hazard Early Warning Systems: Perspectives from the Global South. iScience 28: 112353. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2589004225006145 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Munn, Zachary, Micah D. J. Peters, Cindy Stern, Catalin Tufanaru, Alexa McArthur, and Edoardo Aromataris. 2018. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology 18: 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunbode, Charles A. 2022. Climate justice is social justice in the Global South. Nature Human Behaviour 6: 1443–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, Katja, Ji Yea Cha, Jack Pickles, Charlie Batchelor, and Carlie Stowe. 2021. Towards Disability Transformative Early Warning Systems: Barriers, Challenges, and Opportunities. Available online: https://zcralliance.org/resources/item/towards-disability-transformative-early-warning-systems-barriers-challenges-and-opportunities/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Palm, Jenny. 2009. Placing barriers to industrial energy efficiency in a social context: A discussion of lifestyle categorisation. Energy Efficiency 2: 263–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianta, Mario, and Matteo Lucchese. 2020. Rethinking the European Green Deal: An industrial policy for a just transition in Europe. Review of Radical Political Economics 52: 633–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, Francesca, Marina Cacace, Claudia Aglietti, Luciano d’Andrea, Federico Luigi Marta, Maria Lucinda Fonseca, Alina Esteves, Daniela Ferreira, Giuseppe Pellegrini Masini, Erika Löfström, and et al. 2024. Report on Research Line 8: Toward a Just Mobility Transition. ACCTING Project. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/15520004 (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- PwP. 2018. Stories of Life Change. The Brutal Connection Between Poverty and Deforestation. San Diego: Plant with Purpose. Available online: https://plantwithpurpose.org/stories/poverty-deforestation/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Quinti, Gabriele, and Edoardo Guaschino. 2016. Public Perception of Flood Risk and Social Impact Assessment. Available online: https://www.floodmanagement.info/publications/tools/Tool_25_Public_Perception_of_Flood_Risk_and_Social_Impact_Assessment.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Quinti, Gabriele, Francesca Pugliese, Alain Denis, Aart Kerremans, Giuseppe Pellegrini-Masini, Kenneth Vilhelmsen (NTNU), Vassilis Chatzibirros, Christos Stergiadis, Andrei Holman, and Simona Popusoi. 2024. Report on Research Line 4: Environmental Sustainability and Vulnerability: Cases of Micro-Enterprises Led by Disadvantaged Entrepreneurs. ACCTING Project. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/15525858 (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Qureshi, Zia. 2023. Rising Inequality: A Major Issue of Our Time. Washington, DC: Brookings. [Google Scholar]

- Rege, John E. O., Karen Marshall, An Notenbaert, Julie M. K. Ojango, and Ally M. Okeyo. 2011. Pro-poor animal improvement and breeding—What can science do? Livestock Science 136: 15–28. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1871141310004774 (accessed on 9 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Reid, Hannah, Krystyna Swiderska, Caroline King-Okumu, and Diane Archer. 2015. Vulnerable Communities: Getting Their Needs and Knowledge into Climate Policy. Available online: https://www.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/17328IIED.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- ReliefWeb. 2018. Facilitating Inclusion in Disaster Preparedness: A Practical Guide for CBOs. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/facilitating-inclusion-disaster-preparedness-practical-guide-cbos (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Rey, Freddy, Sylvain Dupire, and Frédéric Berger. 2024. Forest-based solutions for reconciling natural hazard reduction with biodiversity benefits. Nature-Based Solutions 5: 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, Aixa Inés, María Agostina Grígolo, Flavia Emilce Tejada, Alejandra Albarracín, Myriam Patricia Martinez, Romina G. Sales, and Romina Naranjo. 2025. Strategies for teaching natural hazards to children in rural communities. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 116: 105033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkki, Simo, Alice Ludvig, Maria Nijnik, and Serhiy Kopiy. 2022. Embracing policy paradoxes: EU’s Just Transition Fund and the aim “to leave no one behind”. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics 22: 761–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satterthwaite, David. 2017. Addressing the Needs of Vulnerable Groups in Urban Areas. Geneva: UNDRR. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/blog/addressing-needs-vulnerable-groups-urban-areas (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Schor, Juliet B., and Craig J. Thompson, eds. 2014. Sustainable Lifestyles and the Quest for Plenitude: Case Studies of the New Economy. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sekar, Chisholm, K. Christian Jayakumar, and P. Jude. 2023. National Disaster Management Training Module: Psychosocial Preparedness. NDMA; NIMHANS. Available online: https://ndma.gov.in/sites/default/files/PDF/Technical%20Documents/NDMA-Module-3.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Smith, Kristin. 2023. The Unequal Impacts of Flooding. Headwaters Economics: Available online: https://headwaterseconomics.org/natural-hazards/unequal-impacts-of-flooding/#:~:text=Floods%20disproportionately%20impact%20people%20with,areas%2C%20and%20have%20fewer%20resources (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Stevis, Dimitris, and Romain Felli. 2016. Green transitions, just transitions. Kurswechsel 3: 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Stockholm Environment Institute. 2023. Commitment to Impact. Annual Report 2023. Available online: https://www.sei.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/seip10720-annual-report-240426b-web.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Stokel-Walker, Chris. 2022. Dove Finiscono le Nostre Vecchie Auto (Where Our Old Cars End Up). Milano Wired: Available online: https://www.wired.it/article/auto-dove-finiscono-auto-usate-benzina/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Strid, Sofia, Ana B. Vivas, Marina Cacace, Ayşe Gül Altınay, and Burcu Borhan Türeli. 2025. ACCTING Factsheet: Inclusive Civil Society for an Inclusive Green Deal. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/8355807 (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Strid, Sofia, and Carolin Zorell, eds. 2023. D3.2 ACCTING Report on First Cycle Experimental Studies. Confidential Report Delivered to the European Commission 28 April 2023. Brussels: ACCTING (AdvanCing Behavioural Change Through an INclusive Green Deal). [Google Scholar]

- Sufri, Sofyan, Febi Dwirahmadi, Dung Phung, and Shannon Rutherford. 2020. A systematic review of community engagement (CE) in disaster early warning systems (EWSs). Progress in Disaster Science 5: 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan-Wiley, Kira, and Megan Jungwiwattanaporn. 2023. People Who’ve Contributed Least to Climate Change Are Most Affected by It. Washington, DC: PEW. Available online: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2023/05/22/people-whove-contributed-least-to-climate-change-are-most-affected-by-it (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Sultana, Rumana, Haseeb Md Irfanullah, Samiya A. Selim, and Mohammad Budrudzaman. 2023. Vulnerability and ecosystem-based adaptation in the farming communities of droughtprone Northwest Bangladesh. Environmental Challenges 11: 100707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Anh Tran, Phong Tran, Tran Huu Tuan, and Kate Hawley. 2012. Review of Housing Vulnerability: Implications for Climate Resilient Houses. The Sheltering Series No. 1: Sheltering from a Gathering Storm. Available online: https://cdkn.org/sites/default/files/files/Sheltering-from-a-gathering-storm-Discussion-Paper-Series-Review-of-Housing-Vulnerability.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- UNDESA. 2020. Inequality in a Rapidly Changing World. World Social Report 2020. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/desa/world-social-report-2020 (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- UNDESA. 2024. Leveraging the Power and Resilience of Micro-, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (MSMEs) to Accelerate Sustainable Development and Eradicate Poverty in Times of Multiple Crises. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/observances/micro-small-medium-businesses-day (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- UNDP. 2022. What Is Just Transition? And Why Is It Important? New York: UNDP. Available online: https://climatepromise.undp.org/news-and-stories/what-just-transition-and-why-it-important (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- UNDP. 2024a. What Is Climate Change Adaptation and Why Is It Crucial? New York: UNDP. Available online: https://climatepromise.undp.org/news-and-stories/what-climate-change-adaptation-and-why-it-crucial (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- UNDP. 2024b. What Is Climate Change Mitigation and Why Is It Urgent? New York: UNDP. Available online: https://climatepromise.undp.org/news-and-stories/what-climate-change-mitigation-and-why-it-urgent (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- UNESCO. 2024. Disaster Risk Reduction. Early Warning Systems. Paris: UNESCO. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/disaster-risk-reduction/ews (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- UNFCC. 2018. Considerations Regarding Vulnerable Groups, Communities and Ecosystems in the Context of the National Adaptation Plans. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/Considerations%20regarding%20vulnerable.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- United Nations. 2020. Inequality—Bridging the Divide. UN75 and Beyond. New York: United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/un75/inequality-bridging-divide#:~:text=Inequalities%20are%20not%20only%20driven%20and%20measured%20by,which%20continue%20to%20persist%2C%20within%20and%20between%20countries (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- United Nations. 2023. Early Warnings for All. New York: United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/early-warnings-for-all (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Ventura, Luca. 2021. World Wealth Distribution and Income Inequality 2021. Global Finance Magazine, January 11. [Google Scholar]

- Viguié, Vincent, and Stéphane Hallegatte. 2012. Trade-offs and synergies in urban climate policies. Nature Climate Change 2: 334–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WeADAPT. 2024. The Unjust Climate: Measuring Impacts of Climate Change on Rural Poor, Women and Youth. Geneva: UNDRR. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/news/unjust-climate-measuring-impacts-climate-change-rural-poor-women-and-youth#:~:text=Gender%20disparities%20in%20climate%20vulnerability,to%20services%20in%20rural%20areas (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- White, James. 2024. RL1 Italian Country Report on Second Cycle Experimental Studies. Report in Preparation. ACCTING (AdvanCing Behavioural Change Through an INclusive Green Deal). Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/15525938 (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- WMO. 2022. Manual on Community-based Floods and Drought Management in the Volta Basin. Available online: https://www.floodmanagement.info/floodmanagement/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Manual-CBFDM-VB_FinalVersion.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- WMO. 2024. Mainstreaming Gender into End-to-End Flood Forecasting and Early Warning Systems and Integrated Flood Management. Associated Program on Flood Management. Available online: https://www.floodmanagement.info/floodmanagement/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/GenderManual-VB.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- World Bank. 2017. Environmental and Social Framework. Available online: https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/837721522762050108-0290022018/original/ESFFramework.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- World Bank. 2019. Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises -Economic Indicators (MSME-EI) Analysis Note. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/873301627470308867/pdf/Micro-Small-and-Medium-Enterprises-Economic-Indicators-MSME-EI-Analysis-Note.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- World Bank. 2022. Global Program for Resilient Housing. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/disasterriskmanagement/brief/global-program-for-resilient-housing (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Wu, Libo, Zhihao Huang, Xing Zhang, and Yushi Wang. 2024. Harmonizing existing climate change mitigation policy datasets with a hybrid machine learning approach. Scientific Data 11: 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoungrana, Tibi Didier, Aguima Aimé Bernard Lompo, and Daouda Lawa tan Toé. 2024. Effect of climate finance on environmental quality: A global analysis. Research in Economics 78: 100989. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S109094432400053X (accessed on 22 May 2025). [CrossRef]

| Adaptation | Mitigation |

|---|---|

| Avoidance of deforestation/reforestation | Avoidance of deforestation/reforestation |

| Avoidance of houses in flooded areas | Decarbonisation in industry |

| Early warning system (EWS) development | Car-free mobility measures |

| Increased and shared preparedness | Low-emissions buildings |

| Management of emergencies | Sustainable small and micro-enterprises |

| Low-emission livestock |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quinti, G.M.; Marta, F.L. Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Policies: Addressing Unintended Effects on Inequalities. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 368. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060368

Quinti GM, Marta FL. Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Policies: Addressing Unintended Effects on Inequalities. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(6):368. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060368

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuinti, Gabriele M., and Federico L. Marta. 2025. "Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Policies: Addressing Unintended Effects on Inequalities" Social Sciences 14, no. 6: 368. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060368

APA StyleQuinti, G. M., & Marta, F. L. (2025). Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Policies: Addressing Unintended Effects on Inequalities. Social Sciences, 14(6), 368. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060368