Cultural Identity and Virtual Consumption in the Mimetic Homeland: A Case Study of Chinese Generation Z Mobile Game Players

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Analytical Framework: The Mutual Construction of the Virtual and the Reality

3.1. Mimetic Re-Enactment of Real Space

- (1)

- Virtual coexistence

- (2)

- Mimetic homeland

3.2. Emotional Reverse-Nurturing from Virtual to Real Spaces

- (1)

- Theory of Performative Subjectivity

- (2)

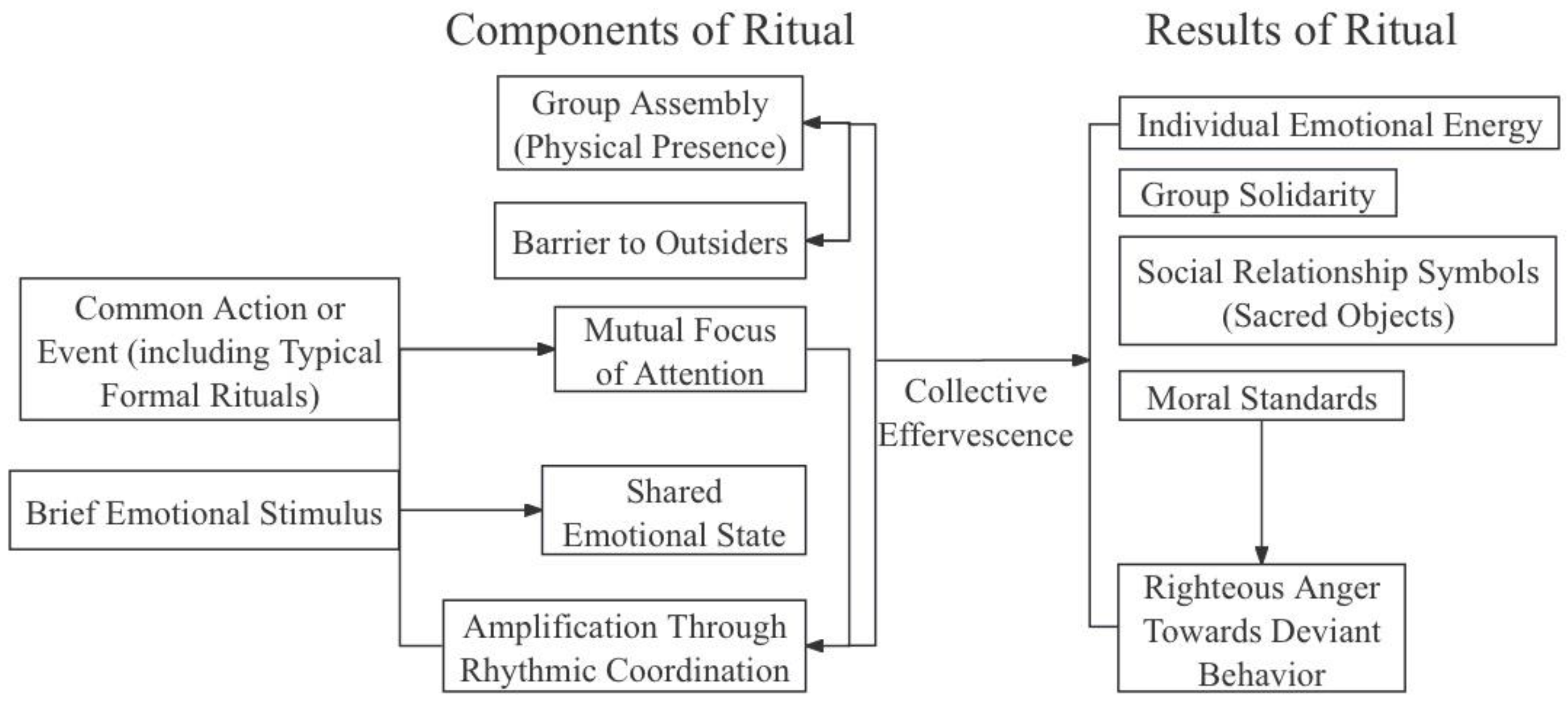

- Interaction Ritual Chains Theory

4. Results

4.1. Virtual Coexistence and the Production of Space

“I don’t buy skins to get stronger. I buy them so others can see I’ve been playing for a long time or that I really love this character. It’s how I show who I am in the game”, said one player.(MSWJS, male, 18, student)

“Sometimes I draw fan art of my favorite characters and post it in gaming groups. People like and share it, and I feel like I’m part of that world—even though I’m not a developer”, said one player.(FSZL, female, 22, student)

“I’m studying abroad, and I don’t have many people around me who speak Chinese. But when I log into a Chinese server, I hear familiar dialects. It makes me feel like I’m home again”, one player shared.(MSWJS, male, 18, student)

“I don’t just play the game—it feels like a familiar place. Every time I log in, it’s like coming home. Even if no one talks to me in real life, there’s always someone waiting to team up in the game”(MSQCY, male, 16, student)

“We have a fixed raid every Friday night. After we finish, we stay on voice chat to talk about real-life stuff. It’s closer than some of my real-world friendships”, one participant explained.(FWGJM, female, 25, company employee)

“I met some friends in a gaming group, and now we’ve met in person. One of them even became my business partner”, said a player.(MWZZX, male, 25, self-employed)

4.2. “Mimetic Homeland” and the Projection of Psychological Needs

- (1)

- The Externalisation of Psychological Needs

“In real life, I don’t have many people to talk to, but in the game, I have a pet. The first thing I do every day is feed it. When it looks happy, I feel happy too.”(FWWYJ, female, 27, company employee)

- (2)

- From Psychological Projection to Emotional Belonging

“My parents keep pressuring me to take civil service exams. Real life feels suffocating. But in the game, I’m a powerful mage who can control the battlefield. It makes me feel like I’m not useless.”(MSZSQ, male, 21, student)

Another participant said, “The game is the only place where I can say ‘no.’ In real life, I’m obedient. But in the game, I can switch characters, leave teams, and start over whenever I want.”(FSWXD, female, 18, student)

4.3. Virtual Consumption and Identity Performance

- (1)

- Virtual Consumption as an Interactive Ritual

“I buy skins to say ‘this is me.’ When you see me wearing this skin, you know I’m a veteran player who takes the game seriously.”(MSWYP, male, 18, student)

Another player added, “I have a limited-edition skin. Every time I use it, people PM me asking how I got it. It makes me feel proud—like I’m not just playing the game, I’m performing a character.”(FSLYY, female, 21, student)

- (2)

- The Reproduction of Cultural Identity

“Ever notice how players put on their most expensive skins during ranked matches? It’s not to win—it’s to intimidate or show off. Just like wearing designer clothes in real life.”(MWXDJ, male, 23, civil servant)

“I bought a matching outfit set just for me and my partner. It’s like telling everyone: we’re a couple—don’t flirt with us.”(FWCHL, female, 24, civil servant)

“I posted a screenshot of my legendary skin on WeChat, and a college classmate reached out saying he played too. That’s how we reconnected.”(MSLKC, male, 22, student)

“I always buy something during festival events—even if it’s useless. I just need that sense of ritual. I don’t even bother that much with real-life holidays.”(MSQCY, male, 16, student)

“I saw my favourite streamer wearing a hoodie from the game’s official collab and I just had to get one too. It feels like I’m carrying a piece of the game with me when I go outside”, noted another player.(FWSJY, female, 24, company employee)

“Honestly, I wouldn’t spend this much on a game if I didn’t feel connected to the story and the characters. The emotional part comes first, then the money”, one player reflected.(MSWYP, male, 18, student)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bai, Fan. 2021. How Emotional Identity Promotes Virtual Consumption: Taking Mobile Game Players as an Example. China Youth Study 11: 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Baudrillard, Jean. 1981. For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign, trans. In Charles Levin. St. Louis: Telos Press, vol. 169, p. 73. [Google Scholar]

- Baudrillard, Jean. 2009. The Transparency of Evil: Essays on Extreme Phenomena. London: Verso Books. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, Ulrich, and Elisabeth Beck-Gernsheim. 2001. Individualization: Institutionalized Individualism and Its Social and Political Consequences. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bericat, Eduardo. 2016. The sociology of emotions: Four decades of progress. Current Sociology 64: 491–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 2017. Habitus. In Habitus: A Sense of Place. London: Routledge, pp. 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Judith, and Gender Trouble. 1990. Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Gender Trouble 3: 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Castronova, Edward. 2005. Synthetic Worlds: The Business and Culture of Online Games. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- China Internet Network Information Center. 2024. Data from: The 53rd Statistical Report on Internet Development in China [Dataset]. Available online: https://www.cnnic.net.cn/NMediaFile/2024/0325/MAIN1711355296414FIQ9XKZV63.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Collins, Randall. 2004. Interaction Ritual Chains. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John W., and Cheryl N. Poth. 2016. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez, Ignacio X., James K. Vance, Rogelio E. Cardona-Rivera, and David L. Roberts. 2016. The mimesis effect: The effect of roles on player choice in interactive narrative role-playing games. Paper presented at 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing System, San Jose, CA, USA, May 7–12; pp. 3438–49. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, Emile. 1912. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Girginova, Katerina. 2025. Global visions for a metaverse. International Journal of Cultural Studies 28: 300–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Tim, Robin Canniford, and Giana M. Eckhardt. 2022. The roar of the crowd: How interaction ritual chains create social atmospheres. Journal of Marketing 86: 121–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, Gert Jan. 2015. Culture’s causes: The next challenge. Cross Cultural Management 22: 545–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, Muzzamel Hussain. 2025. Rene Girard’s Mimetic Theory: A Key To Understanding Religion and Violence in International Relations and Politics. Chinese Political Science Review, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, Henry, and Mizuko Ito. 2015. Participatory Culture in a Networked Era: A Conversation on Youth, Learning, Commerce, and Politics. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Jian, Guideng, and Jiaqi Zhou. 2021. Making Nostalgia: The Spatial Transition and Symbolic Construction of ‘Mimetic Homeland’ in Rural Short Videos. Contemporary TV 12: 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kemper, Theodore D. 2016. Status, Power and Ritual Interaction: A Relational Reading of Durkheim, Goffman and Collins. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Dasol. 2025. Selling Otherness on YouTube: Digital inter-Asian Orientalism and YouTube monetization system. International Journal of Cultural Studies 28: 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, Joachim I. 2008. From social projection to social behaviour. European Review of Social Psychology 18: 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Jiang. 2019. Bodily Performativity and Precarious Life: Judith Butler as Political Philosopher. Journal of Northwest Normal University (Social Sciences) 5: 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, Henri. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford: Basil Backwell. [Google Scholar]

- Lehdonvirta, Vili. 2009. Virtual item sales as a revenue model: Identifying attributes that drive purchase decisions. Electronic Commerce Research 9: 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehdonvirta, Vili. 2010. Online spaces and the construction of identity. Digital Materialities: Design and Anthropology, 76–83. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Linda. 2019. Subject of Power: The Understanding Difference Between Foucault and Judith Butler. World Philosophy 5: 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Ying. 2024. “Mimetic Homeland”: Digital Empowerment of the Spatial Formation of the Shared Spiritual Home of the Chinese Nation. Social Sciences in Xinjiang, 96–106+177. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Peter. 2018. The Role of Virtual Goods in Identity Formation in Online Games. Journal of Virtual Worlds Research 11: 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Nardi, Bonnie. 2010. My Life as a Night Elf Priest: An Anthropological Account of World of Warcraft. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, Celia. 2011. Communities of Play: Emergent Cultures in Multiplayer Games and Virtual Worlds. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Poell, Thomas, David B. Nieborg, Brooke Erin Duffy, Tommy Tse, Bruce Mutsvairo, Arturo Arriagada, Jeroen de Kloet, and Ping Sun. 2025. Global perspectives oan platforms and cultural production. International Journal of Cultural Studies 28: 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, Robert D. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Tina L. 2006. Play Between Worlds: Exploring Online Game Culture. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Tina L. 2015. Raising the Stakes: E-Sports and the Professionalization of Computer Gaming. Cambridge: Mit Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Tina L. 2018. Watch Me Play: Twitch and the Rise of Game Live Streaming. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tönnies, Ferdinand, and Charles P. Loomis. 2017. Community and society. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Turkle, Sherry. 2011. Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yun, and Hanqing Yang. 2023. Making “Nostalgia”: Content Production of Rural Vloggers and Their Professional Identity Generation. Sociological Studies 1: 205–25+230. [Google Scholar]

- Zwass, Vladimir. 2010. Co-Creation: Toward a Taxonomy and an Integrated Research Perspective. International Journal of Electronic Commerce 15: 11–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Interviewee ID | Gender | Age (Years) | Occupation | Annual Virtual Consumption (CNY) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | FSGTY | Female | 18 | Student | 2000 |

| 2 | FSWXD | Female | 18 | Student | 500 |

| 3 | FSLMZ | Female | 20 | Student | 600 |

| 4 | FSLYY | Female | 21 | Student | 900 |

| 5 | FSZL | Female | 22 | Student | 4000 |

| 6 | FSZSJ | Female | 22 | Student | 6000 |

| 7 | FWCHL | Female | 24 | Civil Servant | 300 |

| 8 | FWSJY | Female | 24 | Company Employee | 1000 |

| 9 | FWGJM | Female | 25 | Company Employee | 5000 |

| 10 | FWWYJ | Female | 27 | Company Employee | 500 |

| 11 | MSQCY | Male | 16 | Student | 2000 |

| 12 | MSWJS | Male | 18 | Student | 12,000 |

| 13 | MSWYP | Male | 18 | Student | 3000 |

| 14 | MSZSQ | Male | 21 | Student | 500 |

| 15 | MSLKC | Male | 22 | Student | 1000 |

| 16 | MWXDJ | Male | 23 | Civil Servant | 4000 |

| 17 | MWLMK | Male | 24 | Company Employee | 2000 |

| 18 | MWZZX | Male | 25 | Self-Employed | 10,000 |

| 19 | MWLTY | Male | 27 | Self-Employed | 3000 |

| 20 | MWZTY | Male | 28 | Self-Employed | 1200 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Li, Z.; Chen, X. Cultural Identity and Virtual Consumption in the Mimetic Homeland: A Case Study of Chinese Generation Z Mobile Game Players. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060362

Zhang S, Li Z, Chen X. Cultural Identity and Virtual Consumption in the Mimetic Homeland: A Case Study of Chinese Generation Z Mobile Game Players. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(6):362. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060362

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Shiyi, Zengyu Li, and Xuhua Chen. 2025. "Cultural Identity and Virtual Consumption in the Mimetic Homeland: A Case Study of Chinese Generation Z Mobile Game Players" Social Sciences 14, no. 6: 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060362

APA StyleZhang, S., Li, Z., & Chen, X. (2025). Cultural Identity and Virtual Consumption in the Mimetic Homeland: A Case Study of Chinese Generation Z Mobile Game Players. Social Sciences, 14(6), 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060362