Human Capital Development and Public Health Expenditure: Assessing the Long-Term Sustainability of Economic Development Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

- i.

- To examine public health expenditure’s short- and long-term effects on human development.

- ii.

- To analyse the response of human development to shocks in public health expenditure.

- iii.

- To assess the distributional heterogeneity in the impact of public health expenditure on human development across different levels of development.

- iv.

- To test for the causal relationship between public health expenditure and selected indicators of economic development.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Perspective and Empirical Review

2.2. Gap in Empirical Literature and Development of Hypotheses

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Theoretical Framework and Model Specification

3.2. Techniques of Estimation and Information About the Series

3.2.1. Techniques of Estimation

3.2.2. Information About the Series

4. Presentation of Result and Discussion

4.1. Presentation of Result

4.1.1. Presentation of Preliminary Analysis Results

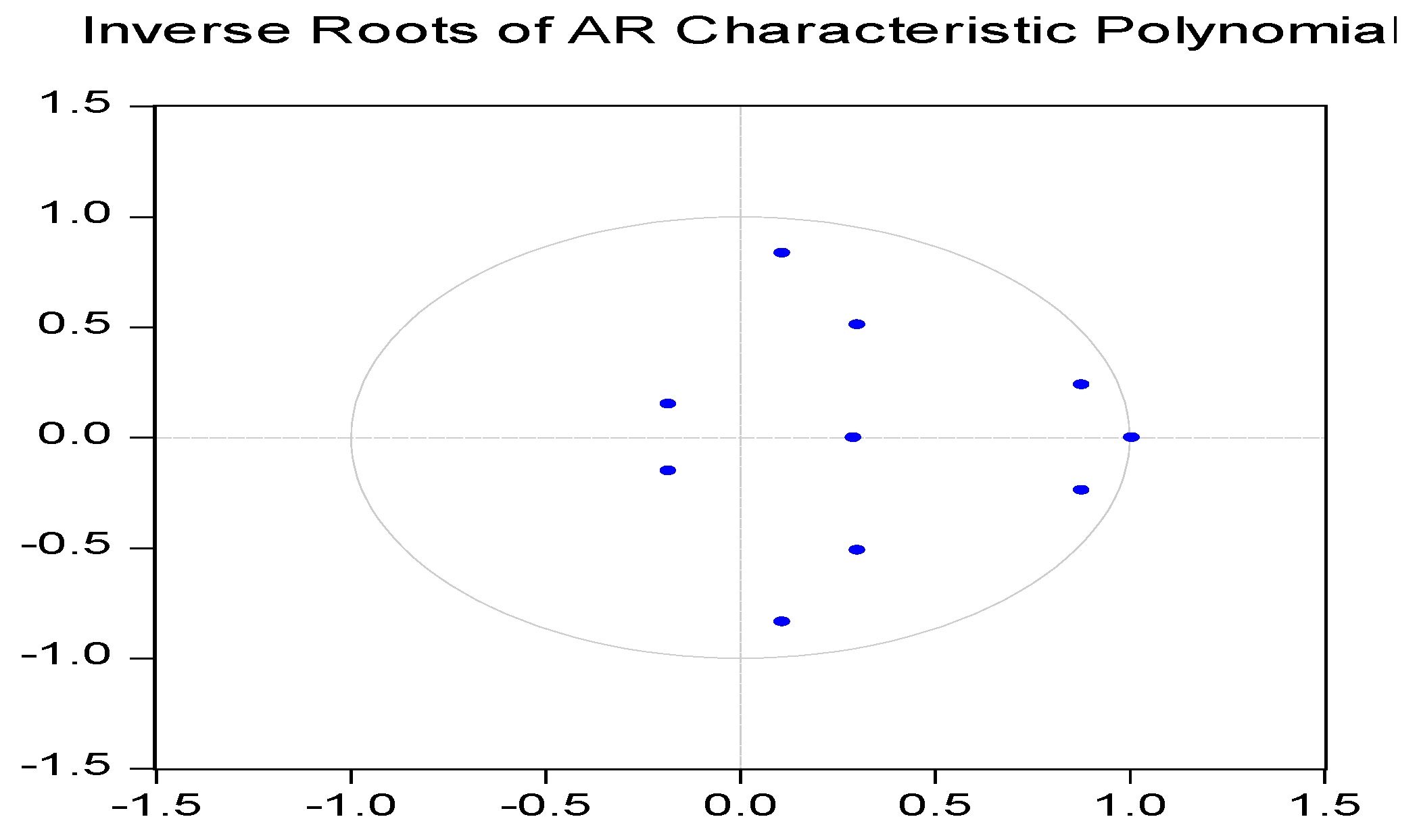

4.1.2. Empirical Results from ARDL, VECM, Causality, and Quantile Regression Analysis

ARDL Results

Variance Decomposition Results

Quantile Regression Results

Pairwise Causality Test Result

4.1.3. Robustness Checks

4.2. Discussion of Results

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Number of Cointegrating Relations by Model | |||||

| Data Trend: | None | None | Linear | Linear | Quadratic |

| Test Type | No Intercept | Intercept | Intercept | Intercept | Intercept |

| No Trend | No Trend | No Trend | Trend | Trend | |

| Trace | 5 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Max-Eig | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Critical values based on MacKinnon, Haug, and Michelis (1999) | |||||

| Selected (0.05 level) | |||||

| Descriptive Statistics | |||||

| HDI | GE | IF | PP | UE | |

| Mean | 0.6132 | 0.6821 | 0.7211 | 0.0459 | 1.2539 |

| Median | 0.6200 | 0.6843 | 0.7577 | 0.0752 | 1.2365 |

| Maximum | 0.7231 | 0.7371 | 1.0032 | 0.3168 | 1.5352 |

| Minimum | 0.5200 | 0.6191 | −0.1598 | −0.4119 | 1.1766 |

| Std. Dev. | 0.0648 | 0.0378 | 0.2266 | 0.1434 | 0.0774 |

| Skewness | 0.0287 | −0.1490 | −2.1611 | −0.9888 | 3.2430 |

| Kurtosis | 1.6308 | 1.6391 | 9.1504 | 5.0492 | 12.0086 |

| Sum | 17.7854 | 19.7817 | 20.9124 | 1.3315 | 36.3638 |

| Sum Sq. Dev. | 0.1176 | 0.0401 | 1.4386 | 0.5765 | 0.1681 |

| Observations | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Correlation Analysis | |||||

| HDI | GE | IF | PP | UE | |

| HDI | 1 | ||||

| GE | 0.7392 | 1 | |||

| IF | 0.0367 | −0.3368 | 1 | ||

| PP | 0.4142 | 0.0253 | 0.2489 | 1 | |

| UE | 0.1727 | 0.6419 | −0.4567 | −0.4492 | 1 |

| Philips Perron Unit Root Test | ||||

| Variables | Model specification | T-Statistics | p-value | Order of Integration |

| HDI | Trend and intercept | −1.8016 | 0.6747 | I (1) |

| D (HDI) | −20,361 ** | 0.0443 | ||

| GE | Trend and intercept | −1.1312 | 0.9038 | I (1) |

| D (GE) | −3.8819 ** | 0.0285 | ||

| IF | Trend and intercept | −3.1638 * | 0.0717 | I (1) |

| D (IF) | −6.6179 *** | 0.0001 | ||

| PP | Trend and intercept | −3.2440 * | 0.0973 | I (1) |

| D (PP) | −11.0534 *** | 0.0000 | ||

| UE | Trend and intercept | −2.6105 | 0.2788 | I (1) |

| D (UE) | −4.4305 *** | 0.0088 | ||

| Augmented Dickey–Fuller Unit Root Test | ||||

| Variables | Model specification | T-Statistics | p-value | Order of Integration |

| HDI | Trend and intercept | −2.8027 | 0.2092 | I (1) |

| D (HDI) | −1.9225 ** | 0.0130 | ||

| GE | Trend and intercept | −1.9225 | 0.613 | I (1) |

| D (GE) | −3.0645 ** | 0.0368 | ||

| IF | Trend and intercept | −4.1741 ** | 0.0416 | I (0) |

| D (IF) | - | - | ||

| PP | Trend and intercept | −3.7072 | 0.0399 | I (1) |

| D (PP) | 0.2835 ** | 0.0471 | ||

| UE | Trend and intercept | −2.7919 | 0.2127 | I (1) |

| D (UE) | −4.5436 *** | 0.0069 | ||

| Statistics | Values | |

| F-Statistics | 9.102 | |

| Significance | Lower Bounds | Upper Bounds |

| 10% | 3.47 | 4.45 |

| 5% | 4.01 | 5.07 |

| 2.50% | 4.52 | 5.62 |

| 1% | 5.17 | 6.36 |

References

- Abdulqadir, Idris Abdullahi, Bello Malam Sa’idu, Ibrahim Muhammad Adam, Fatima Binta Haruna, Mustapha Adamu Zubairu, and Maimunatu Aboki. 2024. Dynamic inference of healthcare expenditure on economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa: A dynamic heterogeneous panel data analysis. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences 40: 145–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achoki, Tom, Benn Sartorius, David Watkins, Scott D. Glenn, Andre Pascal Kengne, Tolu Oni, Charles Shey Wiysonge, Alexandra Walker, Olatunji O Adetokunboh, Tesleem Kayode Babalola, and et al. 2022. Health trends, inequalities and opportunities in South Africa’s provinces, 1990–2019: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease 2019 Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 76: 471–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- African Development Bank. 2024. African Development Bank New Report Highlights Africa’s Strengthening Economic Growth Amid Global Challenges [Press Release]. Available online: https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/press-releases/african-development-bank-new-report-highlights-africas-strengthening-economic-growth-amid-global-challenges-80967 (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Akbar, Minhas, Ammar Hussain, Ahsan Akbar, and Irfan Ullah. 2021. The dynamic association between healthcare spending, CO2 emissions, and human development index in OECD countries: Evidence from panel VAR model. Environment, Development and Sustainability 23: 10470–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Worafi, Yaser Mohammed. 2023. Health Economics in Developing Countries. In Handbook of Medical and Health Sciences in Developing Countries: Education, Practice, and Research. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, Jørgen Goul. 2012. Welfare States and Welfare State Theory. Centre for Comparative Welfare Studies, Institut for Økonomi, Politik og Forvaltning, Aalborg Universitet. CCWS Working Paper. Available online: https://vbn.aau.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/72613349/80_2012_J_rgen_Goul_Andersen.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Androniceanu, Armenia, Jani Kinnunen, and Irina Georgescu. 2021. Circular economy as a strategic option to promote sustainable economic growth and effective human development. Journal of International Studies (2071-8330) 14: 60–73. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=978406 (accessed on 19 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Asaleye, Abiola John, Adeola Phillip Ojo, and Opeyemi Eunice Olagunju. 2023. Asymmetric and shock effects of foreign AID on economic growth and employment generation. Research in Globalization 6: 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaleye, Abiola John, and Thobeka Ncanywa. 2025. Complexity of Renewable Energy and Technological Innovation on Gender-Specific Labour Market in South African Economy. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 11: 100492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaleye, Abiola John, Joseph Olufemi Ogunjobi, and Omotola Adedoyin Ezenwoke. 2021. Trade openness channels and labour market performance: Evidence from Nigeria. International Journal of Social Economics 48: 1589–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem Qureshi, Muhammad. 2009. Human development, public expenditure and economic growth: A system dynamics approach. International Journal of Social Economics 36: 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Kirsten, Jon Adams, and Amie Steel. 2022. Experiences, perceptions and expectations of health services amongst marginalised populations in urban Australia: A meta-ethnographic review of the literature. Health Expectations 25: 2166–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balani, Khushboo, Sarthak Gaurav, and Arnab Jana. 2023. Spending to grow or growing to spend? Relationship between public health expenditure and income of Indian states. SSM-Population Health 21: 101310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, Banna, Chandan Kumar Roy, and Rabiul Hossain. 2023. Healthcare expenditure, good governance and human development. Economia 24: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Gary S. 1964. Human Capita. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research. Available online: http://digamo.free.fr/becker1993.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Bonomi Savignon, Andrea, Lorenzo Costumato, and Benedetta Marchese. 2019. Performance budgeting in context: An analysis of Italian central administrations. Administrative Sciences 9: 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broccia, Sarah, Álvaro Dias, and Leandro Pereira. 2022. Sustainable entrepreneurship: Comparing the determinants of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and social entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Social Sciences 11: 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camminatiello, Ida, Rosaria Lombardo, Mario Musella, and Gianmarco Borrata. 2024. A model for evaluating inequalities in sustainability. Social Indicators Research 175: 879–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Cheng, Xiaohang Ren, Kangyin Dong, Xiucheng Dong, and Zhen Wang. 2021. How does technological innovation mitigate CO2 emissions in OECD countries? Heterogeneous analysis using panel quantile regression. Journal of Environmental Management 280: 111818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danescu, Elena. 2021. Luxembourg Economy: In the Aftermath of the Pandemic. 9780367699369. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10993/50650 (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Dang, Ai-Thu. 2014. Amartya Sen’s Capability approach: A framework for Well-being evaluation and policy analysis. Review of Social Economy 72: 460–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey, David A., and Wayne A. Fuller. 1981. Likelihood ratio statistics for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Econometrica 49: 1057–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edeme, Richardson Kojo, Chigozie Nelson Nkalu, and Innocent A. Ifelunini. 2017. Distributional impact of public expenditure on human development in Nigeria. International Journal of Social Economics 44: 1683–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Anshasy, Amany A., and Usman Khalid. 2023. From diversification resistance to sustainable diversification: Lessons from the UAE’s public policy shift. Management & Sustainability: An Arab Review 2: 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, Madisen, and Puneet Dwivedi. 2019. Assessing changes in inequality for Millennium Development Goals among countries: Lessons for the Sustainable Development Goals. Social Sciences 8: 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaies, Brahim. 2022. Reassessing the impact of health expenditure on income growth in the face of the global sanitary crisis: The case of developing countries. The European Journal of Health Economics 23: 1415–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goga, Sumayya, and Pamela Mondliwa. 2021. Structural transformation, economic power, and inequality in South Africa. In Structural Transformation in South Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 165–88. Available online: https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/50510/9780192894311.pdf?sequence=1#page=194 (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Green, Erik. 2024. Pre-colonial African economies. In Handbook of African Economic Development. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, Michael. 2017. On the concept of health capital and the demand for health. In Determinants of Health: An Economic Perspective. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 6–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, Kobena T. 2024. Natural Resource Management: Global Economic Volatility and Africa’s Growth Prospects. In Routledge Handbook of Natural Resource Governance in Africa. New York: Routledge, pp. 207–21. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781003017479-18/natural-resource-management-kobena-hanson (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Harding, Matthew, Carlos Lamarche, and M. Hashem Pesaran. 2020. Common correlated effects estimation of heterogeneous dynamic panel quantile regression models. Journal of Applied Econometrics 35: 294–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hort, Krishna, Rohan Jayasuriya, and Prarthna Dayal. 2017. The link between UHC reforms and health system governance: Lessons from Asia. Journal of Health Organisation and Management 31: 270–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, Md Saiful. 2022. Impact of socioeconomic development on inflation in South Asia: Evidence from panel cointegration analysis. Applied Economic Analysis 30: 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, Roxanne, Nicolas Farina, and Marguerite Schneider. 2025. Understanding Dementia and Elder Abuse in South Africa: The Challenge of ‘Ageing in Place’ with Dignity. In Navigating Ageing in South Africa: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Singapore: Springer Nature, pp. 175–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, Michelle L., and Rachel Forrester-Jones. 2022. Human-centred design in UK asylum social protection. Social Sciences 11: 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, N., A. H. Kelly, and M. Avendano. 2022. Health equity and health system strengthening time for a WHO re-think. Global Public Health 17: 377–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, Huo, Irfan Khan, Majed Alharthi, Muhammad Wasif Zafar, and Asif Saeed. 2023. Sustainable energy policy, socioeconomic development, and ecological footprint: The economic significance of natural resources, population growth, and industrial development. Utilities Policy 81: 101490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouadio, Michael, and Aloysius Njong Mom. 2024. Health Expenditure, Governance Quality, and Health Outcomes in West African Countries. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management 40: 427–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantion, Danielle Ann, Gabrielle Musñgi, and Ronaldo Cabauatan. 2023. Assessing the Relationship of Human Development Index (HDI) and Government Expenditure on Health and Education in Selected ASEAN Countries. International Journal of Social and Management Studies 4: 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Leoni, Silvia. 2025. A historical review of the role of education: From human capital to human capabilities. Review of Political Economy 37: 227–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loayza, Norman, and Steven Michael Pennings. 2020. Macroeconomic policy in the time of COVID-19: A primer for developing countries. World Bank Research and Policy Briefs 147291. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3586636 (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Lucas, Robert E., Jr. 2009. Ideas and growth. Economica 76: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Peikai, Chenchu Zhang, and Bohui Cheng. 2025. Toward Sustainable Development: The Impact of Green Fiscal Policy on Green Total Factor Productivity. Sustainability 17: 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Ru, and Md Qamruzzaman. 2022. Nexus between government debt, economic policy uncertainty, government spending, and governmental effectiveness in BRIC nations: Evidence for linear and nonlinear assessments. Frontiers in Environmental Science 10: 952452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, Jakob B. 2016. Health, human capital formation and knowledge production: Two centuries of international evidence. Macroeconomic Dynamics 20: 909–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maja, Mengistu M., and Samuel F. Ayano. 2021. The impact of population growth on natural resources and farmers’ capacity to adapt to climate change in low-income countries. Earth Systems and Environment 5: 271–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makwembere, Sandra, Paul Acha-Anyi, Abiola John Asaleye, and Rufaro Garidzirai. 2024. Can Remittance Promote Tourism Income and Inclusive Gender Employment? Function of Migration in the South African Economy. Economies 12: 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manullang, Rizal R., Ellyana Amran, Heppi Syofya, and Iwan Harsono. 2024. The Influence of Government Expenditures on the Human Development Index With Gross Domestic Product As A Moderating Variable. Reslaj: Religion Education Social Laa Roiba Journal 6: 2059–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maphumulo, Winnie T., and Busisiwe R. Bhengu. 2019. Challenges of quality improvement in the healthcare of South Africa post-apartheid: A critical review. Curationis 42: 1–9. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-170ff325f8 (accessed on 19 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Martín-Fernández, Jesús, Ángel López-Nicolás, Juan Oliva-Moreno, Héctor Medina-Palomino, Elena Polentinos-Castro, and Gloria Ariza-Cardiel. 2021. Risk aversion, trust in institutions and contingent valuation of healthcare services: Trying to explain the WTA-WTP gap in the Dutch population. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation 19: 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbau, Rahab, Anita Musiega, Lizah Nyawira, Benjamin Tsofa, Andrew Mulwa, Sassy Molyneux, Isabel Maina, Julie Jemutai, Charles Normand, Kara Hanson, and et al. 2023. Analysing the efficiency of health systems: A systematic review of the literature. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy 21: 205–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Lescano, Ronald, Leonel Muinelo-Gallo, and Oriol Roca-Sagalés. 2023. Human development and decentralisation: The importance of public health expenditure. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics 94: 191–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-García, Nuria, Maria Huertas González-Serrano, Daniel Ordiñana-Bellver, and Salvador Baena-Morales. 2024. Redefining education in sports sciences: A theoretical study for integrating competency-based learning for sustainable employment in Spain. Social Sciences 13: 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, David, and Chris James. 2022. Investing in Health Systems to Protect Society and Boost the Economy: Priority Investments and Order-of-Magnitude Cost Estimates. OECD Health Working Papers, No. 144. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moridian, Ali, Magdalena Radulescu, Parveen Kumar, Maria Tatiana Radu, and Jaradat Mohammad. 2024. New insights on immigration, fiscal policy and unemployment rate in EU countries—A quantile regression approach. Heliyon 10: e33519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nademi, Younes, and Haniyeh Sedaghat Kalmarzi. 2025. Breaking the unemployment cycle using the circular economy: Sustainable jobs for sustainable futures. Journal of Cleaner Production 488: 144655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngene, Nnabuike C., Olive P. Khaliq, and Jagidesa Moodley. 2023. Inequality in health care services in urban and rural settings in South Africa. African Journal of Reproductive Health/La Revue Africaine de la Santé Reproductive 27: 87–95. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-ajrh_v27_n5s_a11 (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Nie, Wan, Antonieta Medina-Lara, Hywel Williams, and Richard Smith. 2021. Do health, environmental and ethical concerns affect purchasing behaviour? A meta-analysis and narrative review. Social Sciences 10: 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuhu, Kaamel M., Justin T. McDaniel, Genevieve A. Alorbi, and Juan I. Ruiz. 2018. Effect of healthcare spending on the relationship between the Human Development Index and maternal and neonatal mortality. International Health 10: 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omri, Henda, Anis Omri, and Abdessalem Abbassi. 2025. Entrepreneurship and Human Well-Being: A Study of Standard of Living and Quality of Life in Developing Countries. Social Indicators Research 177: 313–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onofrei, Mihaela, Anca-Florentina Vatamanu, Georgeta Vintilă, and Elena Cigu. 2021. Government health expenditure and public health outcomes: A comparative study among EU developing countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 10725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, Rachel, Bo Stjerne Thomsen, and Amy Berry. 2022. Learning through play at school—A framework for policy and practice. Frontiers in Education 7: 751801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, Manuel Sousa, António Cardoso, Nourhan M. El Sherbiny, Amândio FC da Silva, Jorge Figueiredo, and Isabel Oliveira. 2025. Exploring the Dimensions of Academic Human Capital: Insights into Enhancing Higher Education Environments in Egypt. Social Sciences 14: 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perron, Pierre. 1989. The great crash, the oil price shock, and the unit root hypothesis. Econometrica 57: 1361–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervaiz, Ruqiya, Faisal Faisal, Sami Ur Rahman, Rajnesh Chander, and Adnan Ali. 2021. Do health expenditure and human development index matter in the carbon emission function for ensuring sustainable development? Evidence from the heterogeneous panel. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health 14: 1773–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M. Hashem, Yongcheol Shin, and Richard J. Smith. 2001. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics 16: 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghupathi, Viju, and Wullianallur Raghupathi. 2020. Healthcare expenditure and economic performance: Insights from the United States data. Frontiers in Public Health 8: 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Railaite, Rasa, and Ruta Ciutiene. 2020. The impact of public health expenditure on health component of human capital. Inžinerinė Ekonomika 31: 371–79. Available online: https://epubl.ktu.edu/object/elaba:67347299/ (accessed on 19 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Rami, Falu, LaShawn Thompson, and Lizette Solis-Cortes. 2023. Healthcare disparities: Vulnerable and marginalised populations. In COVID-19: Health Disparities and Ethical Challenges Across the Globe. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 111–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, Paul M. 1990. Endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy 98: S71–S102. Available online: https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/261725 (accessed on 19 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Runtunuwu, Prince Charles Heston. 2020. Analysis of Macroeconomic Indicators and It’s Effect on Human Development Index (HDI). Society 8: 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, Theodore W. 1961. Investment in Human Capital. The American Economic Review 51: 1–17. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1818907 (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Self, Sharmistha, and Richard Grabowski. 2003. How effective is public health expenditure in improving overall health? A cross–country analysis. Applied Economics 35: 835–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, Narayan, Saileja Mohanty, Aurolipsa Das, and Malayaranjan Sahoo. 2024. Health expenditure and economic growth nexus: Empirical evidence from South Asian countries. Global Business Review 25: S229–S243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silalahi, Masna Sopia, and Sandhy Walsh. 2023. Analysing government policies in addressing unemployment and empowering workers: Implications for economic stability and social welfare. Law and Economics 17: 92–110. Available online: https://journals.ristek.or.id/index.php/LE/article/view/3 (accessed on 19 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Sulla, Victor, Precious Zikhali, and Pablo Facundo Cuevas. 2022. Inequality in Southern Africa: An Assessment of the Southern African Customs Union (English). Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099125303072236903 (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Summers, James Kevin, and Lisa M. Smith. 2014. The role of social and intergenerational equity in making changes in human well-being sustainable. Ambio 43: 718–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, Sabyasachi. 2021. How does urbanisation affect the human development index? A cross-country analysis. Asia-Pacific Journal of Regional Science 5: 1053–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tübbicke, Stefan, and Maximilian Schiele. 2024. On the effects of active labour market policies among individuals reporting to have severe mental health problems. Social Policy & Administration 58: 404–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Țarcă, Viorel, Elena Țarcă, and Mihaela Moscalu. 2024. Social and Economic Determinants of Life Expectancy at Birth in Eastern Europe. Healthcare 12: 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, Ijaz, Muhammad Azam Khan, Muhammad Tariq, Farah Khan, and Zilakat Khan Malik. 2024. Revisiting the determinants of life expectancy in Asia—Exploring the role of institutional quality, financial development, and environmental degradation. Environment, Development and Sustainability 26: 11289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. 2022. Connecting the Dots: Towards a More Equitable, Healthier and Sustainable Future. UNDP HIV and Health Strategy 2022–2025. United Nations Development Programme. New York: One United Nations Plaza. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 1987. 1987: Brundtland Report. Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 2015. The 17 Goals. Department of Economic and Social Affairs Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- United Nations. 2021. Executive Board of the United Nations Development Programme, the United Nations Population Fund and the United Nations Office for Project Services, Second Regular Session 2021, 30 August–2 September, New York, Item 2 of the provisional agenda, UNDP Strategic Plan, 2022–2025. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/board-documents/main-document/ENG_Report_of_the_annual_session_2021_-_Final_-_8Jul21.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. 2020. Socioeconomic Impact of COVID-19 in Southern Africa, May 2020, Lusaka, Zambia. Available online: https://www.uneca.org/sites/default/files/COVID-19/Presentations/socio-economic_impact_of_covid-19_in_southern_africa_-_may_2020.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Van Tulder, Rob, Suzana B. Rodrigues, Hafiz Mirza, and Kathleen Sexsmith. 2021. The UN’s sustainable development goals: Can multinational enterprises lead the decade of action? Journal of International Business Policy 4: 1. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7884867/ (accessed on 19 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Varian, Hal R. 2014. Big data: New tricks for econometrics. Journal of Economic Perspectives 28: 3–28. Available online: https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.28.2.3 (accessed on 19 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- WHO. 2024. A Commitment to Invest in Our Common Health. Geneva: World Health Organisation, Originally published in Al Jazeera on 14 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Widjaja, Gunawan. 2023. Economic Development Transformation with Environmental Vision: Efforts to Create Sustainable and Inclusive Growth. Kurdish Studies 11: 3154–77. Available online: https://kurdishstudies.net/menu-script/index.php/KS/article/view/904 (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Xholo, Namhla, Thobeka Ncanywa, Rufaro Garidzirai, and Abiola John Asaleye. 2025. Promoting Economic Development Through Digitalisation: Impacts on Human Development, Economic Complexity, and Gross National Income. Administrative Sciences 15: 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Xiaoxuan. 2020. Health expenditure, human capital, and economic growth: An empirical study of developing countries. International Journal of Health Economics and Management 20: 163–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, Gulizar Seda. 2024. Does a Financing Scheme Matter for Access to Healthcare Services? In Integrated Science for Sustainable Development Goal 3: Universal Good Health and Well-Being. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, pp. 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Caichun, Wenwu Zhao, Francesco Cherubini, and Paulo Pereira. 2021. Integrate ecosystem services into socioeconomic development to enhance achievement of sustainable development goals in the post-pandemic era. Geography and Sustainability 2: 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolanda, Y. 2017. Analysis of Factors Affecting Inflation and Its Impact on Human Development Index and Poverty in Indonesia. Available online: https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/33040 (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Zaman, Mubasher, Atta Ullah, Chen Pinglu, and Muhammad Kashif. 2024. Sustainable Silk Road Future: Examining the nexus of inflation, regional integration, globalisation and sustainability in BRI economies. Sustainable Futures 7: 100172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Long-run ARDL ECM results | ||||

| Dependent variable: HDI | ||||

| Variable | Coefficients | Standard Error | t-statistics | Prob. |

| GE | 0.2897 *** | 0.0384 | 7.5374 | 0.0000 |

| IF | 0.0170 *** | 0.0057 | 2.9952 | 0.0091 |

| UE | −0.0038 ** | 0.0229 | −0.1681 | 0.0187 |

| PP | −0.0102 ** | 0.0043 | −2.3697 | 0.0316 |

| Constant | −0.4500 *** | 0.0637 | −7.0605 | 0.0000 |

| Short-run elasticities and ECM | ||||

| Dependent variable: HDI | ||||

| Variables | Coefficient | Standard error | t-Statistics | Prob. |

| GE | 0.0170 *** | 0.0020 | 4.2250 | 0.000 |

| IF | 0.0100 ** | 0.0040 | 2.3210 | 0.031 |

| PP | 0.0100 | 0.0070 | 1.4190 | 0.171 |

| UE | 0.2276 *** | 0.0645 | 3.7940 | 0.004 |

| Coint. Equation (−1) | −0.1650 *** | 0.0190 | −8.2983 | 0.000 |

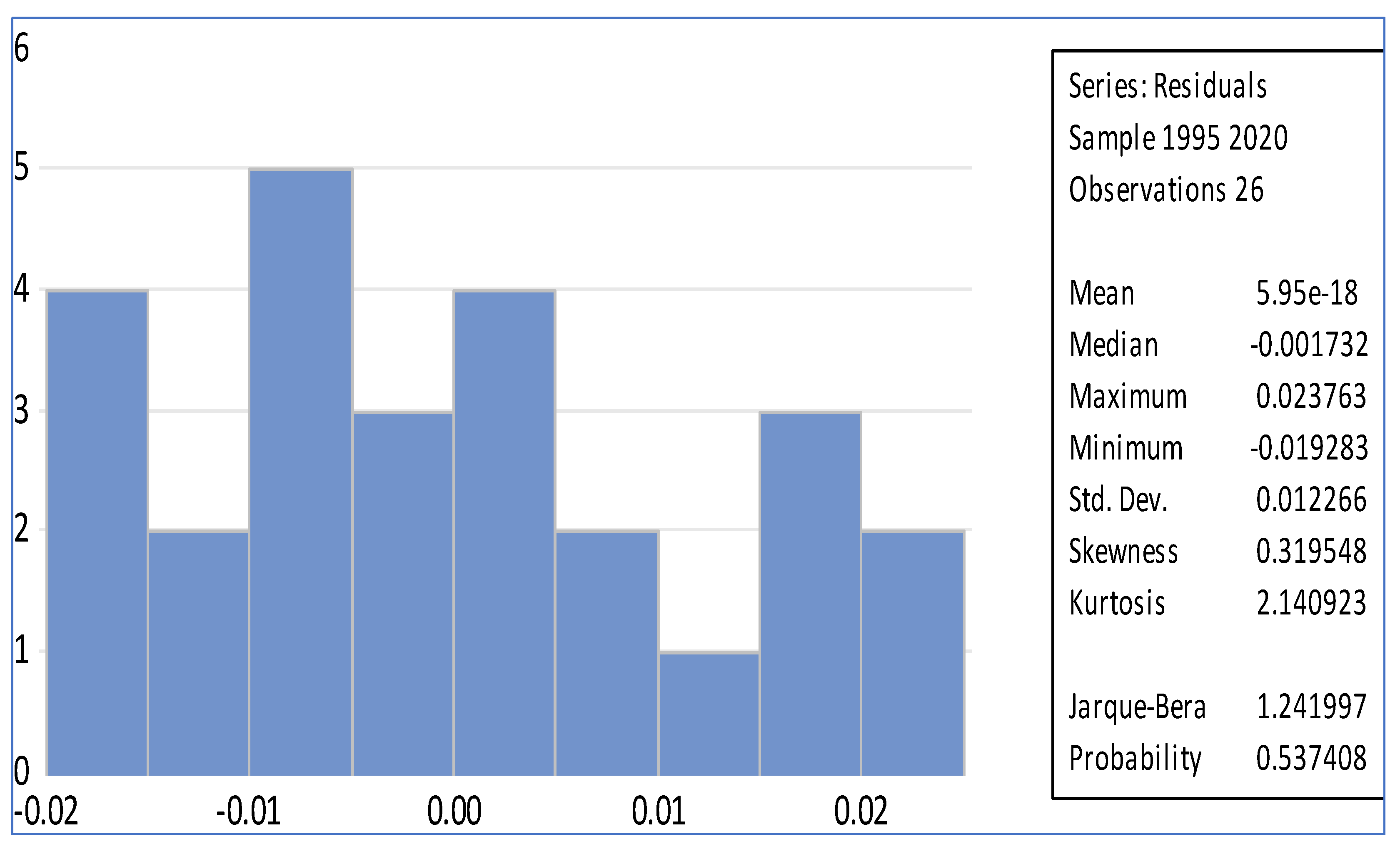

| Diagnostic Checks | ||||

| Serial Correlation | ||||

| F-Statistics | 1.569 | Prob. | 0.226 | |

| Obs R Squared | 2.085 | Prob. | 0.148 | |

| Heteroscedasticity test: Breusch pagan test | ||||

| F-statistics | 0.989 | Prob. | 0.46 | |

| Obs R-Squared | 6.188 | Prob. | 0.402 | |

| Scales explained SS | 1.88 | Prob. | 0.929 | |

| Normality Test | ||||

| Jargue–Bera | 1.2419 | Prob. | 0.5374 | |

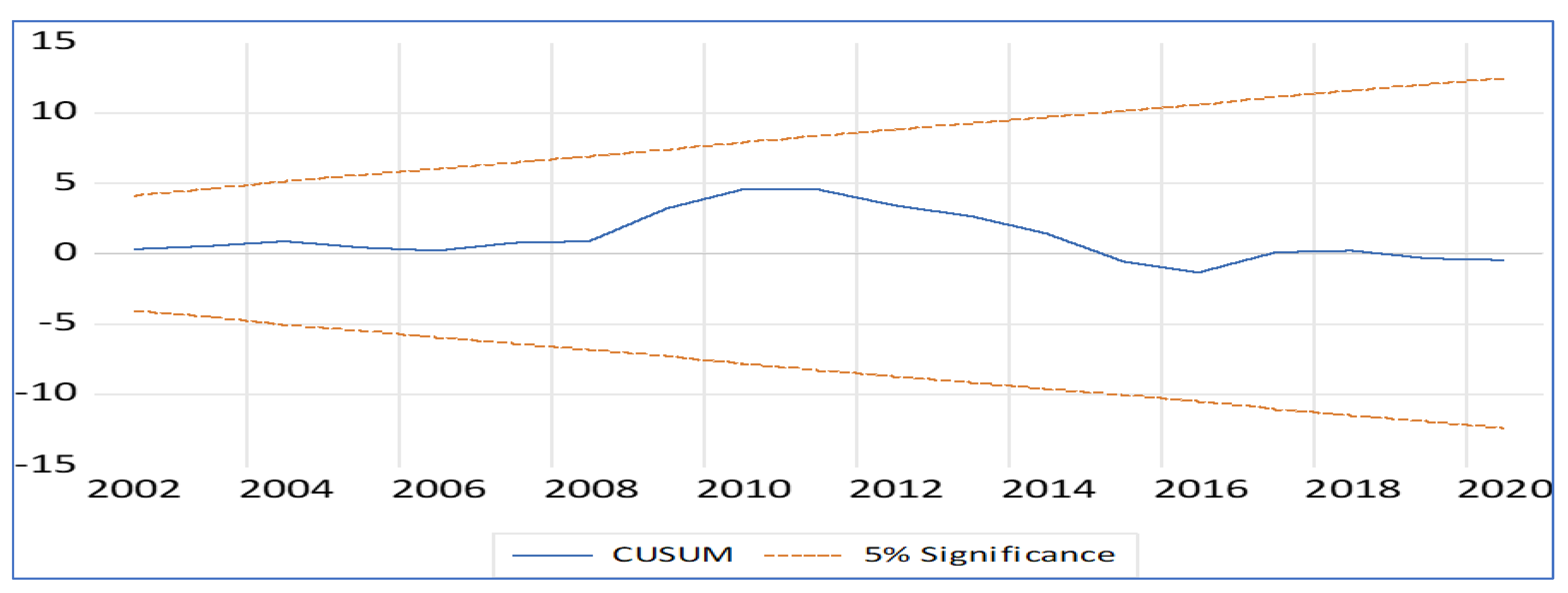

| Stability Test | ||||

| Cusum Test | Stable | |||

| CusumQ Test | Stable | |||

| Variance Decomposition of GE | |||||

| Period | GE | UE | IF | PP | HDI |

| 1 | 100 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| 2 | 94.9652 | 1.1011 | 2.0441 | 0.0100 | 1.8792 |

| 3 | 84.9152 | 10.2512 | 2.8804 | 0.4194 | 1.5335 |

| 4 | 85.2194 | 9.5591 | 3.1651 | 0.7517 | 1.3045 |

| 5 | 86.5861 | 8.4227 | 3.0780 | 0.6601 | 1.2528 |

| 6 | 87.4363 | 7.4694 | 3.1370 | 0.5837 | 1.3733 |

| 7 | 81.3784 | 13.4090 | 2.8936 | 1.0529 | 1.2659 |

| 8 | 80.5236 | 14.4543 | 2.7775 | 1.1115 | 1.1329 |

| 9 | 81.6557 | 13.4143 | 2.8190 | 1.0173 | 1.0934 |

| 10 | 82.2931 | 12.7143 | 2.8643 | 0.9493 | 1.1787 |

| Dependent Variable: HDI | ||||

| tau = 0.2 | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

| GE | −0.0638 | 0.5289 | −0.1206 | 0.9050 |

| IF | 0.0088 | 0.0445 | 0.1980 | 0.8447 |

| UE | 0.8160 *** | 0.2640 | 3.0902 | 0.0050 |

| PP | 0.4156 *** | 0.1479 | 2.8094 | 0.0097 |

| C | −0.4359 * | 0.2211 | −1.9711 | 0.0603 |

| tau = 0.4 | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

| GE | 0.4393 | 0.4215 | 1.0422 | 0.3077 |

| IF | 0.0260 | 0.0516 | 0.5039 | 0.6189 |

| UE | 0.5708 ** | 0.2448 | 2.3318 | 0.0284 |

| PP | 0.3646 ** | 0.1661 | 2.1953 | 0.0381 |

| C | −0.4510 ** | 0.2150 | −2.0973 | 0.0467 |

| tau = 0.6 | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

| GE | 0.7485 * | 0.3712 | 2.0163 | 0.0551 |

| IF | 0.0413 | 0.0613 | 0.6734 | 0.5071 |

| UE | 0.5274 * | 0.2719 | 1.9395 | 0.0643 |

| PP | 0.3347 | 0.2137 | 1.5664 | 0.1303 |

| C | −0.6006 ** | 0.2575 | −2.3321 | 0.0284 |

| tau = 0.8 | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

| GE | 0.9445 ** | 0.3564 | 2.6495 | 0.0140 |

| IF | 0.1246 ** | 0.05923 | 2.104295 | 0.0460 |

| UE | 0.0330 | 0.162797 | 0.203025 | 0.8408 |

| PP | 0.0283 | 0.097551 | 0.290615 | 0.7738 |

| C | −0.11497 | 0.293531 | −0.391685 | 0.6987 |

| Null Hypothesis: | F-Statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|

| 2.2896 | 0.1249 | |

| 4.9120 ** | 0.0172 | |

| 0.1947 | 0.8244 | |

| 0.0567 | 0.9450 | |

| 0.0128 | 0.9872 | |

| 0.1424 | 0.8680 | |

| 0.0929 | 0.9116 | |

| 0.9994 | 0.3842 | |

| 0.5710 | 0.5731 | |

| 0.1880 | 0.8299 | |

| 0.3792 | 0.6887 | |

| 0.1758 | 0.8399 | |

| 0.2004 | 0.8198 | |

| 1.2257 | 0.3128 | |

| 0.9681 | 0.3954 | |

| 0.8762 | 0.4304 | |

| 0.02283 | 0.9775 | |

| 0.53323 | 0.5941 | |

| 0.58017 | 0.5681 | |

| 0.26144 | 0.7723 |

| Dependent Variable: HDI | ||||

| Fully Modified Least Squares (FMOLS) | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

| GE | 1.1206 *** | 0.3341 | 3.3536 | 0.0028 |

| IF | 0.0899 * | 0.0508 | 1.7696 | 0.0901 |

| UE | 0.2703 | 0.1676 | 1.6118 | 0.1206 |

| PP | −0.1989 ** | 0.0876 | −2.2696 | 0.0329 |

| C | −0.5597 ** | 0.2516 | −2.2240 | 0.0362 |

| R-squared | 0.6295 | Adjusted R-squared | 0.5477 | |

| Canonical Cointegrating Regression (CCR) | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

| GE | 1.1257 *** | 0.3099 | 3.6319 | 0.0010 |

| IF | 0.0820 | 0.0560 | 1.4625 | 0.1571 |

| UE | 0.2755 | 0.2140 | 1.2871 | 0.2109 |

| PP | −0.1988 * | 0.0989 | −2.0098 | 0.0563 |

| C | −0.5648 * | 0.2907 | −1.9427 | 0.0644 |

| R-squared | 0.6396 | Adjusted R-squared | 0.559634 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Magida, N.; Ncanywa, T.; Sibanda, K.; Asaleye, A.J. Human Capital Development and Public Health Expenditure: Assessing the Long-Term Sustainability of Economic Development Models. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 351. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060351

Magida N, Ncanywa T, Sibanda K, Asaleye AJ. Human Capital Development and Public Health Expenditure: Assessing the Long-Term Sustainability of Economic Development Models. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(6):351. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060351

Chicago/Turabian StyleMagida, Ngesisa, Thobeka Ncanywa, Kin Sibanda, and Abiola John Asaleye. 2025. "Human Capital Development and Public Health Expenditure: Assessing the Long-Term Sustainability of Economic Development Models" Social Sciences 14, no. 6: 351. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060351

APA StyleMagida, N., Ncanywa, T., Sibanda, K., & Asaleye, A. J. (2025). Human Capital Development and Public Health Expenditure: Assessing the Long-Term Sustainability of Economic Development Models. Social Sciences, 14(6), 351. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060351