Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has disrupted society, economy and family life. However, the impact of the pandemic on well-being in child-rearing families has not been fully studied, particularly regarding the changes before and during the pandemic and its long-term effects. This systematic review aimed to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on family well-being by focusing on changes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our systematic review (PROSPERO protocol ID: CRD42023420175) extracted 2148 references from MEDLINE, CINAHL and PsycINFO, including 15 longitudinal studies published between January 2020 and October 2024. We examined the association between COVID-19 and the well-being of child-rearing families following the PRISMA guidelines. The level of family functioning and parent–child relationship quality generally declined during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic situation, while family chaos and conflict increased. However, some families reported improved functioning and no significant changes in family satisfaction. Overall, the impact of the pandemic on family well-being varied by region. These findings suggest that healthcare providers should continue to monitor dynamic family health and provide targeted support.

1. Introduction

Although the COVID-19 pandemic has largely passed, social and economic disturbances have emerged, collectively straining public health systems and adversely affecting personal well-being (Gadermann et al. 2021; Prime et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2021). Discrimination, slander and bullying, along with a surge in false rumors and misinformation, fueled public discontent toward governments and communities. Furthermore, widespread isolation led to job losses, diminished economic activity and supply shortages. Individual behaviors also shifted noticeably; people became more reluctant to travel or go out, and there were observable increases in alcohol and tobacco consumption. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic had negative impacts not only on individuals but also on families (Gayatri and Puspitasari 2023).

Two previous reviews have examined the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on family well-being, highlighting the significant consequences for well-being of both individual family members and the overall family. A literature review by Gayatri and Puspitasari (2023) showed that changes in family dynamics, financial stress and mental health challenges affected the overall well-being of family members. Furthermore, a scoping review by Soejima (2021) showed that regardless of whether family members had a disease or disability, the COVID-19 pandemic has been associated with health and well-being in all families (e.g., worsened family relationships, reduced family cohesion and increased family cohesion) and individual family members (e.g., sleep disturbance and increased psychological problems). Notably, however, both reviews largely focused on the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic and included both qualitative and quantitative studies, making it difficult to draw clear causal inferences. Hence, there remains a gap in understanding the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on families, as well as the changes in family well-being before and after the pandemic. Additionally, these studies did not provide a detailed classification of different types of families, such as child-rearing and older families. Most studies have focused on the impact of this global crisis on the mental well-being of older adults and adolescents (Hanno et al. 2022; Machlin et al. 2022). Prime et al. (2020) predicted that the societal disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic could have adverse consequences for family health; this includes impacts on parental well-being and children’s adjustment, as well as the effects on family relationships and functioning. To address these gaps, our review focuses specifically on longitudinal studies of child-rearing families, examining how the COVID-19 pandemic affected family well-being over time.

Families suddenly and unexpectedly faced a multitude of stressors due to COVID-19 (e.g., school closures, additional parenting burdens and financial stress). This has had a downstream effect on all families, including parents and children (Pecor et al. 2021). A mixed study reported worsened relationships between parents during the COVID-19 lockdown (Gadermann et al. 2021). Meanwhile, Chinese mothers reported less family cohesion and more family conflict and independence during the pandemic than before (Xie et al. 2021). In a multinational study, families with children reported experiencing low quality of life (QOL) (Shah et al. 2021). Due to the pandemic’s potentially worsening and enduring impact on family well-being, child-rearing families should be the focus of relevant research. However, no systematic report has comprehensively explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the well-being of families with children.

According to the family systems theory (Bowen 2004), a family has an interconnected and interdependent system, where the quality of interactions among members and the system’s adaptive capacity determine its functional state. When families face external stressors, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, their ability to adapt and cope directly influences their overall well-being. Especially for child-rearing families, these dynamics are even more crucial, as parents’ well-being directly affects their children’s care, development and overall well-being. Furthermore, Walsh’s family resilience model emphasizes that, during periods of significant stress or adversity, the core elements, including family belief systems, organizational patterns and communication and problem-solving processes, are crucial for sustaining family functioning and well-being (Walsh 2003, 2016). Based on the family systems theory (Bowen 2004) and Walsh’s family resilience model (Walsh 2003, 2016), an operational definition of family well-being refers to the quality of interactions among family members, the adaptive capacity of the family system and the overall functional state of the family as an interconnected and interdependent system in the face of external stressors (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic).

This study addresses the following research question: How did the COVID-19 pandemic impact the well-being of child-rearing families? This systematic review aimed to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on family well-being by focusing on changes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Materials and Methods

Our systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines (Page et al. 2021). We included original quantitative studies that focused on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the well-being of child-rearing families. The inclusion criteria included studies examining the longitudinal impact of the pandemic, including comparisons of family well-being before and after the pandemic. The protocol for this systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (Protocol ID: CRD42023420175).

2.1. Search Strategy and Information Sources

We conducted a literature search using three electronic databases: MEDLINE, CINAHL and PsycINFO. Studies published between January 2020 and October 2024 were identified. In this review, we used controlled vocabulary terms. The terms regarding the COVID-19 pandemic were “COVID-19” or “novel coronavirus”. The terms referring to child-rearing families were “family with child” or “families with child” or “child raising family” or “child raising families”. The search results for articles on the COVID-19 pandemic were combined with those of the search for articles on child-rearing families. These terms were selected to capture studies focusing on the family unit during the child-rearing phase.

The studies for the review were selected based on the following inclusion criteria to explore the long-term impact of the pandemic on child-rearing families: (1) published in English; (2) associated with the COVID-19 pandemic; (3) longitudinal quantitative study (defined as a study that collected data from the same group of participants at two or more time points); and (4) focused on family well-being, defined as the overall functioning and quality of interactions within families with children under 18 years of age, including dimensions such as family relationships, family cohesion, family chaos, family functioning, family conflict and family satisfaction. Studies that focused on individual mental health were excluded.

2.2. Quality Appraisal

The methods of the longitudinal studies incorporated in this analysis were evaluated using the Observational Cohort Study Quality Assessment Tools, as developed by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI n.d.). This tool evaluates 14 key methodological criteria, including (1) clarity of research objectives, (2) specification of study population, (3) participation rate validity, (4) consistency in subject selection, (5) sample size justification, (6) temporality between exposure and outcome, (7) sufficiency of follow-up timeframe, (8) measurement validity of exposures and outcomes, (9) control of confounding factors, (10) statistical adjustment for potential biases, (11) validity and reliability, (12) blinding of outcome assessors, (13) follow-up rate and (14) control of confounding factors through statistical adjustment. Each criterion was evaluated with one of the following responses: “Yes”, “No”, “Cannot Determine (CD)”, “Not Applicable (NA)” or “Not Reported (NR)”, with an overall quality classification (Good, Fair and Poor) based on cumulative risk of bias.

Two researchers (Q.L. and S.Z.) independently conducted the assessments and resolved discrepancies through consensus (Table 1). While the NHLBI tool provides guidance for quality classification, we followed Sanderson et al.’s recommendation to avoid quality classification judgments (e.g., “Good/Fair/Poor”) given the lack of consensus thresholds for observational studies (Sanderson et al. 2007). The overall Kappa was 0.52 (95% CI: 0.38–0.66), indicating moderate agreement between the two evaluators (Landis and Koch 1977).

2.3. Use of AI Tools

We used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4) to help improve the wording of this paper. The tool was not used for planning the study, analyzing data or interpreting the results. We reviewed and edited our manuscript to ensure that the meaning was accurate and that the content was our own.

3. Results

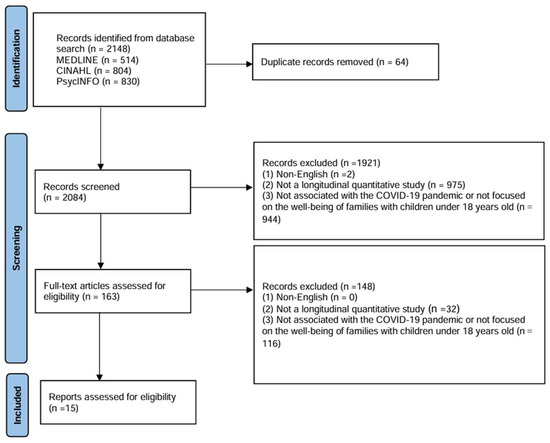

The systematic search across three databases (CINAHL, MEDLINE and PsycINFO) identified 2148 potentially relevant articles (Figure 1). Of the 2148 articles, 64 duplicate articles were removed. After screening 2084 candidate articles through title and abstract assessment, 1921 publications were eliminated. The reasons for exclusion were as follows: 2 articles were published in non-English languages, 975 were not original quantitative research papers, and 944 were not associated with the COVID-19 pandemic and did not focus on the well-being of child-rearing families. A total of 163 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, and 148 were excluded (116 articles were excluded, as they did not examine COVID-19-related impacts and did not focus on families with children under 18 years old. Additionally, 32 articles were removed because they were not longitudinal in design). Finally, 15 articles were included in the analysis.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart depicting the process of article search and inclusion.

Of the 15 articles reviewed, 7 focused on the US, 3 on Canada and 1 each on the UK, Germany, Italy, New Zealand and the UAE (Table 2). The sample sizes of the included studies ranged from 107 to 2921, with a median of 456. Regarding the family structure, two studies (Feinberg et al. 2022; Overall et al. 2022) specifically focused on heterosexual dual-parent families, and two studies (Browne et al. 2021; Cassinat et al. 2021) reported on the composition of the families (e.g., single-parent, dual-parent families or same-sex partners). The remaining 11 studies did not provide information on the family structure. The number of measurement points ranged from 2 to 16. Among the longitudinal studies, five discussed the changes in family well-being before and during the COVID-19 pandemic period (Aman et al. 2023; Cassinat et al. 2021; Conway and Feinberg 2025; Feinberg et al. 2022; Hanno et al. 2022). Additionally, ten articles described changes in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Among these, six studies focused on family well-being in 2020 (Browne et al. 2021; Essler et al. 2021; Fosco et al. 2022; Nocentini et al. 2024; Overall et al. 2022; Rizeq et al. 2021), while four examined family well-being over one year or longer, spanning from 2020 to 2021 (Lee et al. 2023, 2024; Overall et al. 2022; Von Suchodoletz et al. 2023).

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies (n = 15).

Table 1.

Results of methodological quality assessment.

Table 1.

Results of methodological quality assessment.

| Quality Assessment Criteria | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

| Browne et al. (2021) | + | + | NR | + | − | + | + | NA | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| Cassinat et al. (2021) | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | NA | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| Rizeq et al. (2021) | + | + | CD | + | − | + | + | NA | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| Essler et al. (2021) | + | + | CD | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| Fosco et al. (2022) | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | NA | + | + |

| Overall et al. (2022) | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | NA | + | + | + | NA | + | + |

| Hanno et al. (2022) | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + |

| Feinberg et al. (2022) | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| Aman et al. (2023) | + | + | CD | + | − | + | + | NA | + | − | + | − | CD | + |

| Lee et al. (2023) | + | + | CD | + | − | + | + | NA | + | + | + | − | CD | + |

| Von Suchodoletz et al. (2023) | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + |

| Nocentini et al. (2024) | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | NA | + | + | + | − | − | + |

| Lee et al. (2025) | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | CD | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| Lee et al. (2024) | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | CD | + | − | + | + | CD | + |

| Conway and Feinberg (2025) | + | + | NA | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | CD | + |

Note. +, yes; −, no; CD, Cannot Determine; NA, Not Applicable; NR, Not Reported. Quality assessment criteria: 1 = Was the research question or objective in this paper clearly stated? 2 = Was the study population clearly specified and defined? 3 = Was the participation rate of eligible persons at least 50%? 4 = Were all the subjects selected or recruited from the same or similar populations (including the same time period)? Were inclusion and exclusion criteria for being in the study prespecified and applied uniformly to all participants? Question 5. Was a sample size justification, power description, or variance and effect estimates provided? 6 = For the analyses in this paper, were the exposure(s) of interest measured prior to the outcome(s) being measured? 7 = Was the timeframe sufficient, so that one could reasonably expect to see an association between exposure and outcome if it existed? 8 = For exposures that can vary in amount or level, did the study examine different levels of the exposure as related to the outcome (e.g., categories of exposure or exposure measured as a continuous variable)? 9 = Were the exposure measures (independent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable and implemented consistently across all study participants? 10 = Was/were the exposure(s) assessed more than once over time? 11 = Were the outcome measures (dependent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable and implemented consistently across all study participants? 12 = Were the outcome assessors blinded to the exposure status of participants? 13 = Was failure to follow-up after baseline 20% or less? 14 = Were the key potential confounding variables measured and adjusted statistically for their impact on the relationship between exposure(s) and outcome(s)?

Three studies focused on family functioning (Aman et al. 2023; Browne et al. 2021; Rizeq et al. 2021), and eight studies examined family relationships, including parent–child, partner and sibling relationships (Cassinat et al. 2021; Conway and Feinberg 2025; Essler et al. 2021; Feinberg et al. 2022; Lee et al. 2023, 2024; Overall et al. 2022; Von Suchodoletz et al. 2023). Four studies investigated family cohesion (Conway and Feinberg 2025; Fosco et al. 2022; Lee et al. 2024; Overall et al. 2022).

3.1. Changes in Family Well-Being Before vs. During the COVID-19 Pandemic

In the US, two studies have indicated a decline in relationship quality during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, Feinberg et al. (2022) found that co-parenting quality decreased significantly during the early months of the pandemic, while Conway and Feinberg (2025) reported that 57% of parents experienced a reduction in co-parenting relationship quality compared to pre-pandemic baselines. Cassinat et al. (2021) showed an increase in family chaos during the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, a study from Canada found that some families experienced improved functioning during the COVID-19 pandemic (Aman et al. 2023). Moreover, a study from Italy showed no significant changes in family satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to pre-pandemic levels (Nocentini et al. 2024).

3.2. Changes in Family Well-Being During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Rizeq et al. found that in Canada, parent and child mental health difficulties, coupled with heightened parental stress during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, predicted a decline in family functioning over time (Rizeq et al. 2021). Material deprivation due to the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated family dysfunction by increasing parental stress and mental health difficulties (Rizeq et al. 2021). Moreover, Browne et al. (2021) demonstrated that greater COVID-19-related disruptions in the UK were linked to impaired family functioning, which significantly mediated the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on parental mental health (Browne et al. 2021).

Two studies reported a deterioration in parent–child relationships, particularly in families experiencing higher levels of stress and conflict (Lee et al. 2024, 2025). Von Suchodoletz et al. (2023) reported that during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UAE, concerns about infection and financial stress were positively associated with parental stress. Higher levels of parental stress were linked to more marital relationship problems and lower parent–child relationship quality (Von Suchodoletz et al. 2023). However, the parent–child relationship quality slightly decreased over time from the early lockdown period to the second researched timeframe when restrictions were loosened (Essler et al. 2021). Furthermore, the impact of parental strain on children’s well-being and problem behaviors was moderated by parent–child relationship quality, with stronger effects observed when positive relationship quality was low (Essler et al. 2021).

Hanno et al. (2022) found that in the US, parents reported higher levels of family chaos and parent–child conflict in the middle of the shutdown compared to its early stages. Similarly, Overall et al. (2022) found that family satisfaction and cohesion significantly declined during the lockdown, while parental relationship problems and family chaos increased. Lee et al. (2024) showed that in the US, children in families with lower cohesion, higher conflict and greater chaos exhibited more internalizing problems compared to those in families with higher cohesion and lower conflict and chaos (Lee et al. 2024). Additionally, Fosco et al. (2022) reported that disruptions in family cohesion were associated with a high risk for child internalizing problems; moreover, disruptions in family conflict were significantly associated with elevated risks for both child internalizing and externalizing problems.

3.3. Quality Assessment Results

Detailed criteria-level evaluations are documented in Table 1 to provide a transparent report on the methodological strengths and limitations.

All studies demonstrated adherence to the clarity of research objectives, specifications of study populations and validity of exposure and outcome measures, with 100% rated as “YES”. In addition, the temporality between exposure and outcome and sufficiency of the follow-up timeframe were also addressed in 93% and 87% of studies, respectively. However, notable variability was observed in the control of confounding factors, with all studies reporting “YES”. Statistical adjustments for potential biases were less consistent, with 47% rated as “NO” or “NR”. The measurements at different exposure levels showed different results. Sample size justification was lacking in 73% of the studies, and blinding of outcome assessors was not reported in 67% of the studies.

4. Discussion

In this systematic review, we provide evidence elucidating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the well-being of child-rearing families and examine how the pandemic influenced family well-being by exploring its effects on family functioning, relationships, conflict, chaos, cohesion and satisfaction. The 15 studies included in this review covered seven countries and focused on families with children. While a decline in co-parenting relationship quality and an increase in family chaos were observed, some families reported improvements in family functioning and no significant changes in family satisfaction. During the COVID-19 pandemic, family functioning and cohesion were significantly affected. Family conflicts and chaos increased. Parent–child and marital relationships also deteriorated, particularly in families facing higher levels of stress and financial strain. However, one study has also found a buffering role of positive relationship quality and partner support in mitigating these negative impacts (Conway and Feinberg 2025).

This review reveals that during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, co-parenting quality declined compared to the situation before the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the family stress model, economic hardship is a critical factor that exacerbates parental distress and undermines the family environment (Conger et al. 1994). Conway and Feinberg (2025) also noted that middle-income families in particular may have already been under considerable stress before the COVID-19 pandemic. The additional economic strain from the COVID-19 pandemic likely intensified these existing pressures, leading to a decline in co-parenting quality. In addition, families had to adapt to social isolation, school or daycare closures and remote work, all of which increased the overall stress levels within the household, which may have directly elevated parental distress and subsequently diminished co-parenting quality. Furthermore, during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, parents were required to take on multiple roles simultaneously, including staying at home, supervising their children’s remote learning and managing household chores (Lebow 2020). Especially for working parents, managing the dual responsibilities of their jobs and their children’s studies was particularly challenging. These multiple roles may increase parental stress, leading to altered parenting attitudes and patience levels. Moreover, several studies have indicated co-parenting quality as a crucial protective factor during crises, capable of mitigating the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic (Conway and Feinberg 2025; Daks et al. 2020). Therefore, enhancing parental support services and strengthening co-parenting interventions are necessary.

Previous reviews, such as Soejima (2021) and Gayatri and Puspitasari (2023), which examined cross-sectional and qualitative studies related to the COVID-19 pandemic, have focused on the short-term effects of the pandemic on family members and reported that, during the pandemic, family members experienced increased anxiety and depression. This review, incorporating longitudinal research, focused on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on family well-being as a whole rather than on the impact on individual family members. Studies analyzing longitudinal data collected before and during the COVID-19 pandemic have explained the causal relationship of the impact of COVID-19 on the well-being of child-rearing families. This highlights the need for interventions targeting not only individuals but also entire families to address the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This review provides evidence of COVID-19 pandemic’s direct and indirect impacts on family well-being based on the results of longitudinal studies. Direct impacts include disruptions to family functioning, increased family chaos and deteriorating parent–child relationships (Cassinat et al. 2021; Conway and Feinberg 2025; Essler et al. 2021; Feinberg et al. 2022; Hanno et al. 2022; Overall et al. 2022). For instance, in a two-wave longitudinal analysis, Cassinat et al. (2021) found that the COVID-19 pandemic led to a significant increase in family chaos, as reported by parents over time. The COVID-19 pandemic also indirectly affected family well-being through economic hardship, parental mental health issues and reduced social support (Browne et al. 2021; Essler et al. 2021; Fosco et al. 2022; Lee et al. 2024, 2025; Rizeq et al. 2021; Von Suchodoletz et al. 2023). For example, Overall et al. found that partner support moderated the relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and family dynamics, such that higher levels of partner support attenuated the increase in relationship problems and family chaos, as well as the decline in family satisfaction and family cohesion. Previous studies have also indicated that the pandemic had reduced the availability of social support networks, crucial for maintaining positive family relationships (Pietromonaco and Overall 2021; Long et al. 2022). The lack of external support made it harder for families to cope with internal stressors (Prime et al. 2020; Soejima 2021). Thus, to mitigate the long-term negative effects of public health concerns, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, on family well-being, healthcare providers should implement comprehensive measures, including psychological counseling and emotional support for parents, along with social support, to resolve family conflicts and strengthen relationships. Moreover, co-parenting interventions are vital. Developing evidence-based online co-parenting courses (e.g., modules on conflict resolution, child-centered scheduling and stress management) and community workshops facilitated by family therapists could systematically enhance co-parenting quality. Future research should evaluate the efficacy of these interventions through randomized controlled trials, with particular attention to culturally adapted programs for diverse family structures.

This study had some limitations. First, many studies included in our review focused on the short-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic; among the longitudinal studies, only a subset had follow-up intervals exceeding one year. Second, we described the dynamic changes in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic; establishing a direct causal link between these changes and the COVID-19 pandemic itself remains challenging. Third, most of the included studies were conducted in Western countries, such as the US and Canada, which may not be fully generalizable to families in east Asian or other non-Western cultural contexts. Only a small number of studies explicitly reported the family type (e.g., heterosexual two-parent families), and subgroup analyses by family structure were generally lacking. These limitations restrict the extent to which our findings can be generalized to all family types or across diverse sociocultural contexts. Moreover, only one study (Cassinat et al. 2021) indicated the type of family as a control variable, which may limit the ability to account for its influence on family well-being outcomes. In addition, our search strategy focused on child-rearing families. Broader terms like “parenting” and “parent–child” were not explicitly included, which may have limited the comprehensiveness of the literature retrieved. Finally, only five studies addressed regression to the mean or clearly reported how sample attrition was handled (Essler et al. 2021; Feinberg et al. 2022; Hanno et al. 2022; Overall et al. 2022; Rizeq et al. 2021). Although some studies used robust longitudinal models (e.g., CLPM, HLM), inconsistent reporting limits our ability to assess potential bias.

Future studies should focus on sustained long-term studies to fully explore the long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on family well-being. For instance, future research should further examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on families in east Asian or other non-Western cultural contexts. Moreover, studies should also consider diverse family structures to determine how these differences may moderate the impact of public health crises.

5. Conclusions

Our systematic review identified changes in family well-being among child-rearing families before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. While some families showed stable or improved functioning, others experienced increased family chaos, declines in co-parenting quality and deteriorating parent–child relationships. These negative changes were often associated with parental stress, mental health difficulties and reduced social support. Our findings contribute to a better understanding of the changes in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic, offering insights into developing tailored interventions. To mitigate the long-term negative effects of public health crises on family well-being, interventions such as psychological counseling, emotional support and co-parenting programs are essential to strengthen family functioning and resilience. Further studies are necessary to explore the long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on family well-being during the child-rearing period and assess how different family structures adapt to public health crises in diverse cultural contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.L. and T.S.; methodology, Q.L., S.Z., M.K. and T.S.; investigation, Q.L.; data curation, Q.L. and S.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.L.; writing—review and editing, Q.L., S.Z., M.K. and T.S.; visualization, Q.L. and T.S.; supervision, M.K. and T.S.; project administration, Q.L. and T.S.; and funding acquisition, Q.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Kobe University Premium Program (grant number 206k012k) And APC was funded by the grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (c)), grant number 22K11060.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article material. Further inquiries can be directed to the first author or corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful for funding from the Kobe University Premium Program and the staff for their cooperation in this study. During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI) in order to improve the wording of this paper. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed, and they take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aman, Nowrin F., Jessica Fitzpatrick, Isabel De Verteuil, Jovanka Vasilevska-Ristovska, Tonny H. M. Banh, Daphne J. Korczak, and Rulan S. Parekh. 2023. Family functioning and quality of life among children with nephrotic syndrome during the first pandemic wave. Pediatric Nephrology 38: 3193–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, Murray. 2004. Family Therapy in Clinical Practice. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, Dillon T., Mark Wade, Shealyn S. May, Jennifer M. Jenkins, and Heather Prime. 2021. COVID-19 disruption gets inside the family: A two-month multilevel study of family stress during the pandemic. Developmental Psychology 57: 1681–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassinat, Jenna R., Shawn D. Whiteman, Sarfaraz Serang, Aryn M. Dotterer, Sarah A. Mustillo, Jennifer L. Maggs, and Brian C. Kelly. 2021. Changes in family chaos and family relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology 57: 1597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, Rand D., Xiaojia Ge, Glen H. Elder, Frederick O. Lorenz, and Ronald L. Simons. 1994. Economic Stress, Coercive Family Process, and Developmental Problems of Adolescents. Child Development 65: 541–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daks, Jelena S., Jennifer S. Peltz, and Ronald D. Rogge. 2020. Psychological Flexibility and Inflexibility as Sources of Resiliency and Risk during a Pandemic: Modeling the Cascade of COVID-19 Stress on Family Systems with a Contextual Behavioral Science Lens. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science 18: 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, C. Andrew, and Mark Feinberg. 2025. Long-term effects of changes in coparenting quality during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Family Psychology 39: 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essler, Samuel, Natalie Christner, and Markus Paulus. 2021. Longitudinal relations between parental strain, parent-child relationship quality, and child well-being during the unfolding COVID-19 pandemic. Child Psychiatry and Human Development 52: 995–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, Mark E., Jacqueline A. Mogle, Jin-Kyung Lee, Samantha L. Tornello, Michelle L. Hostetler, Joseph A. Cifelli, Sunhye Bai, and Emily Hotez. 2022. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on parent, child, and family functioning. Family Process 61: 361–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosco, Gregory M., Carlie J. Sloan, Shichen Fang, and Mark E. Feinberg. 2022. Family vulnerability and disruption during the COVID-19 pandemic: Prospective pathways to child maladjustment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 63: 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadermann, Anne C., Kimberly C. Thomson, Chris G. Richardson, Monique Gagné, Corey McAuliffe, Saima Hirani, and Emily Jenkins. 2021. Examining the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on family mental health in Canada: Findings from a national cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 11: e042871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayatri, Maria, and Mardiana D. Puspitasari. 2023. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on family well-being: A literature review. Family Journal 31: 606–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanno, Emily C., Jorge Cuartas, Luke W. Miratrix, Stephanie M. Jones, and Nonie K. Lesaux. 2022. Changes in children’s behavioral health and family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 43: 168–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, Richard J., and Gary G. Koch. 1977. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 33: 159–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebow, Jay L. 2020. The challenges of COVID-19 for divorcing and post-divorce families. Family Process 59: 967–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Hyanghee, Gregory M. Fosco, and Mark E. Feinberg. 2025. Family functioning and child internalizing and externalizing problems: A 16-wave longitudinal study during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Development 96: 426–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Janelle B., Kharah M. Ross, Henry Ntanda, Kirsten M. Fiest, Nicole Letourneau, and the APrON Study Team. 2023. Mothers’ and children’s mental distress and family strain during the COVID-19 pandemic: A prospective cohort study. Children 10: 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Joyce Y. Y., Shawna J. J. Lee, Sehun Oh, Amy Xu, Angelise Radney, and Christina M. M. Rodriguez. 2024. Family stress processes underlying COVID-19–related economic insecurity for mothers and fathers and children’s internalizing behaviour problems. Child & Family Social Work. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Emily, Susan Patterson, Karen Maxwell, Carolyn Blake, Raquel Bosó Pérez, Ruth Lewis, Mark McCann, Julie Riddell, Kathryn Skivington, Rachel Wilson-Lowe, and et al. 2022. COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on social relationships and health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 76: 128–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machlin, Laura, Meredith A. Gruhn, Adam B. Miller, Helen M. Milojevich, Summer Motton, Abigail M. Findley, Kinjal Patel, Amanda Mitchell, Dominique N. Martinez, and Margaret A. Sheridan. 2022. Predictors of family violence in North Carolina following initial COVID-19 stay-at-home orders. Child Abuse and Neglect 130: 105376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI). (n.d.). Study Quality Assessment Tools; National Institutes of Health. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Nocentini, Annalaura, Benedetta E. Palladino, Enrico Imbimbo, and Ersilia Menesini. 2024. Pathways to resilience: The parallel change in children’s emotional difficulties and family context during the COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. In Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy. vol. 16 (Suppl. 1), pp. S106–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overall, Nickola C., Rachel S. T. Low, Valerie T. Chang, Annette M. E. Henderson, Caitlin S. McRae, and Paula R. Pietromonaco. 2022. Enduring COVID-19 lockdowns: Risk versus resilience in parents’ health and family functioning across the pandemic. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 39: 3296–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, and et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Medicine 18: e1003583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pecor, Keith, Georgia Barbayannis, Max Yang, Jacklyn Johnson, Sarah Materasso, Mauricio Borda, Disleidy Garcia, Varsha Garla, and Xue Ming. 2021. Quality of Life Changes during the COVID-19 Pandemic for Caregivers of Children with ADHD and/or ASD. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietromonaco, Paula R., and Nickola C. Overall. 2021. The Social and Economic Impact of COVID-19 on Family Functioning and Well-Being: Where Do We Go from Here? Journal of Family Theory & Review 13: 258–72. [Google Scholar]

- Prime, Heather, Mark Wade, and Dillon T. Browne. 2020. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist 75: 631–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizeq, Jala, Daphne J. Korczak, Katherine Tombeau Cost, Evdokia Anagnostou, Alice Charach, Suneeta Monga, Catherine S. Birken, Elizabeth Kelley, Rob Nicolson, Spit for Science, and et al. 2021. Vulnerability pathways to mental health outcomes in children and parents during COVID-19. Current Psychology 42: 17348–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, Simon, Iain D. Tatt, and Julian P. T. Higgins. 2007. Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: A systematic review and annotated bibliography. International Journal of Epidemiology 36: 666–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Rubina, Faraz M. Ali, Stuart J. Nixon, John R. Ingram, Sam M. Salek, and Andrew Y. Finlay. 2021. Measuring the impact of COVID-19 on the quality of life of the survivors, partners and family members: A cross-sectional international online survey. BMJ Open 11: e047680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soejima, Takafumi. 2021. Impact of the coronavirus pandemic on family well-being: A rapid and scoping review. Open Journal of Nursing 11: 1064–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Suchodoletz, Antje, Jocelyn Bélanger, Christopher Bryan, Rahma Ali, and Sheikha R. Al Nuaimi. 2023. COVID-19’s shadow on families: A structural equation model of parental stress, family relationships, and child wellbeing. PLoS ONE 18: e0292292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Froma. 2003. Family resilience: A framework for clinical practice. Family Process 42: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Froma. 2016. Strengthening Family Resilience, 3rd ed. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Zhenlin, Pui L. Yeung, and Xiaozi Gao. 2021. Under the same roof: Parents’ COVID-related stress mediates the associations between household crowdedness and young children’s problem behaviors during social distancing. Current Research in Ecological and Social Psychology 2: 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Miaomiao, Xiaoyun Wang, Jingjing Zhang, and Yi Wang. 2021. Alteration in the psychologic status and family environment of pregnant women before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 153: 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).