The Experience of Transition from Hospital to Community Care of Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Qualitative Narrative Review of Patients’, Families’ and Healthcare Professionals’ Perspectives

Abstract

1. Background

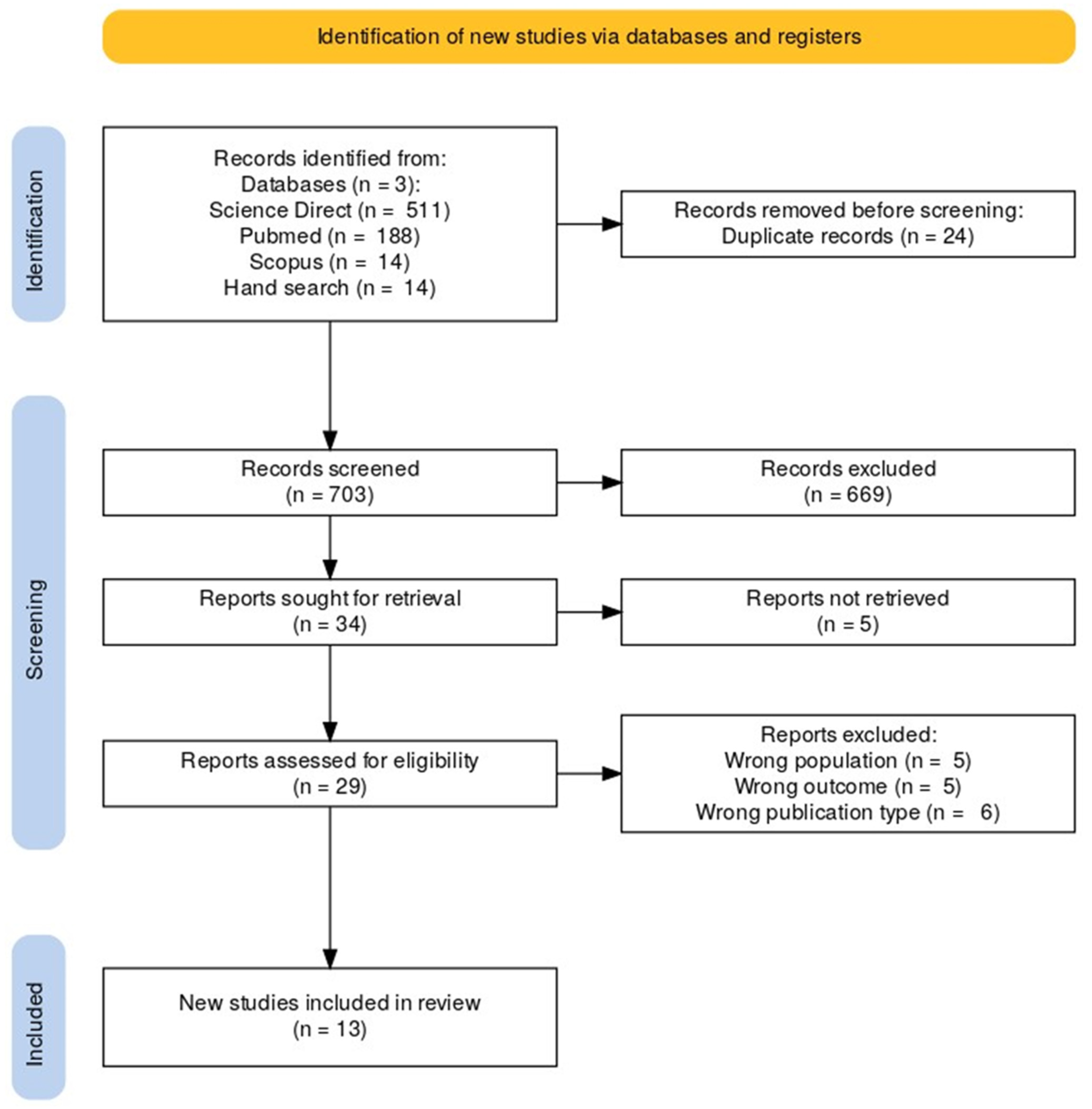

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Data Synthesis and Analysis

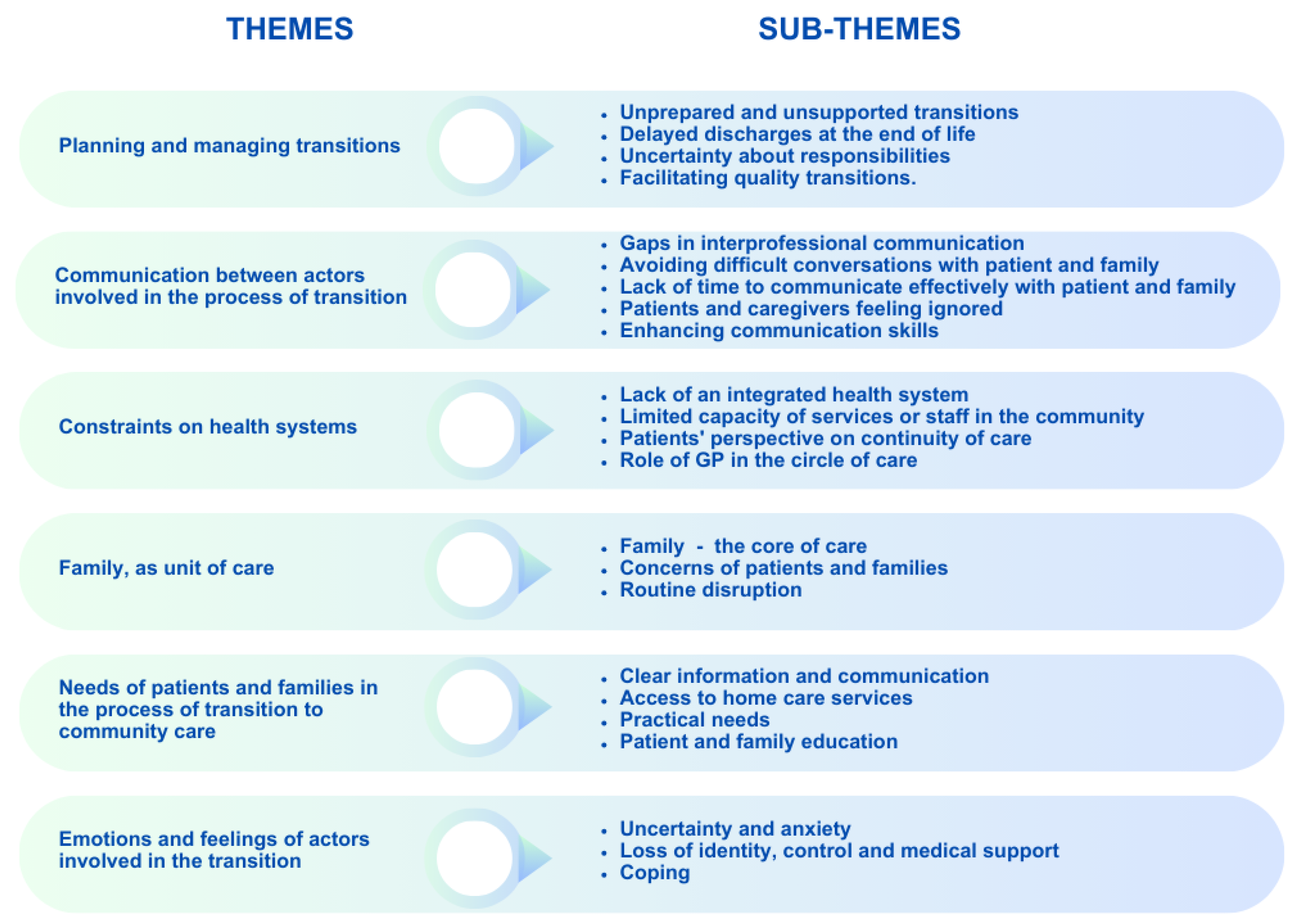

3. Results

3.1. Planning and Managing Transitions

3.1.1. Unprepared and Unsupported Transitions

3.1.2. Delayed Discharges at the End of Life

3.1.3. Uncertainty About Responsibilities

3.1.4. Facilitating Quality Transitions

3.2. Communication Between Actors Involved in the Process of Transition

3.2.1. Gaps in Interprofessional Communication

3.2.2. Avoiding Difficult Conversations with Patient and Family

3.2.3. Lack of Time to Communicate Effectively with Patient and Family

3.2.4. Patients and Caregivers Feeling Ignored

3.2.5. Enhancing Communication Skills

3.3. Constraints on Health Systems

3.3.1. Lack of an Integrated Health System

3.3.2. Limited Capacity of Services or Staff in the Community

3.3.3. Patients’ Perspective on Continuity of Care

3.3.4. Role of GP in the Circle of Care

3.4. Family, as Unit of Care

3.4.1. Family—Essential Support in Care

3.4.2. Concerns of Patients and Families

3.4.3. Routine Disruption

3.5. Needs of Patients and Families in the Process of Transition to Community Care

3.5.1. Clear Information and Communication

3.5.2. Access to Home Care Services

3.5.3. Practical Needs

3.5.4. Patient and Family Education

3.6. Emotions and Feelings of Actors Involved in the Transition

3.6.1. Uncertainty and Anxiety

3.6.2. Loss of Identity, Control, and Medical Support

3.6.3. Coping

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aamodt, Ina Marie Thon, Irene Lie, and Ragnhild Hellesø. 2013. Nurses’ perspectives on the discharge of cancer patients with palliative care needs from a gastroenterology ward. International Journal of Palliative Nursing 19: 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abarshi, Ebun, Michael Echteld, Lieve Van den Block, Ge Donker, Luc Deliens, and Bregje Onwuteaka-Philipsen. 2010. Transitions between care settings at the end of life in The Netherlands: Results from a nationwide study. Palliative Medicine 24: 166–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzar, Emma, Lissi Hansen, Anna W. Kneitel, and Erik K. Fromme. 2011. Discharge Planning for Palliative Care Patients: A Qualitative Analysis. Journal of Palliative Medicine 14: 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berterö, Carina, Maria Vanhanen, and Gunilla Appelin. 2008. Receiving a diagnosis of inoperable lung cancer: Patients’ perspectives of how it affects their life situation and quality of life. Acta Oncologica 47: 862–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blay, Nicole, Christine M. Duffield, and Robyn Gallagher. 2012. Patient transfers in australia: Implications for nursing workload and patient outcomes: Patient transfers in Australia. Journal of Nursing Management 20: 302–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chick, Norma, and Afaf Ibrahim Meleis. 1986. Transitions: A Nursing Concern. Boulder: Aspen Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, Eric A., and Chad Boult. 2003. Improving the Quality of Transitional Care for Persons with Complex Care Needs: Position Statement of The American Geriatrics Society Health Care Systems Committee. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 51: 556–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Committee on Improving the Quality of Cancer Care. 2013. Committee on Improving the Quality of Cancer Care: Addressing the Challenges of an Aging Population, Board on Health Care Services, Institute of Medicine. In Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Edited by Laura A. Levit, Erin Balogh, Sharyl J. Nass and Patricia Ganz. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, Maureen, Tracy Long-Sutehall, Anne-Sophie Darlington, and Alison Richardson. 2015. Doctors’ and nurses’ views and experience of transferring patients from critical care home to die: A qualitative exploratory study. Palliative Medicine 29: 354–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlan, Michael, and Patricia Cronin. 2021. Doing a Literature Review in Nursing, Health and Social Care. New York: Sage Publication Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, Patricia, Frances Ryan, and Michael Coughlan. 2008. Undertaking a literature review: A step-by-step approach. British Journal of Nursing 17: 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon-Woods, Mary, Shona Agarwal, David Jones, Bridget Young, and Alex Sutton. 2005. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: A review of possible methods. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 10: 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Dose, Ann Marie, Lori M. Rhudy, Diane E. Holland, and Marianne E. Olson. 2011. The Experience of Transition from Hospital to Home Hospice: Unexpected Disruption. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing 13: 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggleby, Wendy D., Kelly L. Penz, Donna M. Goodridge, Donna M. Wilson, Beverly D. Leipert, Patricia H. Berry, Sylvia R. Keall, and Christopher J. Justice. 2010. The transition experience of rural older persons with advanced cancer and their families: A grounded theory study. BMC Palliative Care 9: 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flierman, Isabelle, Rosanne van Seben, Marjon van Rijn, Marjolein Poels, Bianca M. Buurman, and Dick L. Willems. 2020. Health Care Providers’ Views on the Transition Between Hospital and Primary Care in Patients in the Palliative Phase: A Qualitative Description Study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 60: 372–80.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasparyan, Armen Yuri, Lilit Ayvazyan, Heather Blackmore, and George D. Kitas. 2011. Writing a narrative biomedical review: Considerations for authors, peer reviewers, and editors. Rheumatology International 31: 1409–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, Barbara, and Irene J. Higginson. 2006. Factors influencing death at home in terminally ill patients with cancer: A systematic review. BMJ 332: 515–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Bart N., Claire D. Johnson, and Alan Adams. 2006. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: Secrets of the trade. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine 5: 101–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, Trisha, Sally Thorne, and Kirsti Malterud. 2018. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? European Journal of Clinical Investigation 48: e12931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Ping, Cathryn Pinto, Beth Edwards, Sophie Pask, Alice Firth, Suzanne O’Brien, and Fliss E. M. Murtagh. 2022. Experiences of transitioning between settings of care from the perspectives of patients with advanced illness receiving specialist palliative care and their family caregivers: A qualitative interview study. Palliative Medicine 36: 124–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanratty, Barbara, Louise Holmes, Elizabeth Lowson, Gunn Grande, Julia Addington-Hall, Sheila Payne, and Jane Seymour. 2012. Older Adults’ Experiences of Transitions Between Care Settings at the End of Life in England: A Qualitative Interview Study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 44: 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higginson, Irene J., and G. J. A. Sen-Gupta. 2000. Place of Care in Advanced Cancer: A Qualitative Systematic Literature Review of Patient Preferences. Journal of Palliative Medicine 3: 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higginson, Irene J., Barbara A. Daveson, R. Sean Morrison, Deokhee Yi, Diane Meier, Melinda Smith, Karen Ryan, Regina McQuillan, Bridget M. Johnston, and Charles Normand. 2017. Social and Clinical Determinants of Preferences and Their Achievement at the End of Life: Prospective Cohort Study of Older Adults Receiving Palliative Care in Three Countries. BMC Geriatrics 17: 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Anita, Kim Jameson, and Carol Pavlish. 2016. An exploratory study of interprofessional collaboration in end-of-life decision-making beyond palliative care settings. Journal of Interprofessional Care 30: 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohmann, Natalie S., Cassidi C. McDaniel, S. Walker Mason, Winson Y. Cheung, Michelle S. Williams, Carolina Salvador, Edith K. Graves, Christina N. Camp, and Chiahung Chou. 2020. Healthcare providers’ perspectives on care coordination for adults with cancer and multiple chronic conditions: A systematic review. Journal of Pharmacy and Health Services Research 11: 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Cancerología E.S.E., M. Arias Rojas, C. García-Vivar, and Universidad de Navarra. 2015. The transition of palliative care from the hospital to the home: A narrative review of experiences of patients and family caretakers. Investigación y Educación en Enfermería 33: 482–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenberg, Sarina R., Tieghan Killackey, Stephanie Saunders, Mary Scott, Natalie C. Ernecoff, Shirley H. Bush, Jaymie Varenbut, Emily Lovrics, Maya A. Stern, and Amy T. Hsu. 2021. Going Home [Is] Just a Feel-Good Idea with No Structure: A Qualitative Exploration of Patient and Family Caregiver Needs When Transitioning from Hospital to Home in Palliative Care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 62: e9–e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffs, Lianne, Simon Kitto, Jane Merkley, Renee F. Lyons, and Chaim M. Bell. 2012. Safety threats and opportunities to improve interfacility care transitions: Insights from patients and family members. Patient Preference and Adherence 2012: 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasdorf, Alina, Gloria Dust, Vera Vennedey, Christian Rietz, Maria C. Polidori, Raymond Voltz, and Julia Strupp. 2021. What Are the Risk Factors for Avoidable Transitions in the Last Year of Life? A Qualitative Exploration of Professionals’ Perspectives for Improving Care in Germany. BMC Health Services Research 21: 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killackey, Tieghan, Emily Lovrics, Stephanie Saunders, and Sarina R. Isenberg. 2020. Palliative care transitions from acute care to community-based care: A qualitative systematic review of the experiences and perspectives of health care providers. Palliative Medicine 34: 1316–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kripalani, Sunil, Frank LeFevre, Christopher O. Phillips, Mark V. Williams, Preetha Basaviah, and David W. Baker. 2007. Deficits in Communication and Information Transfer Between Hospital-Based and Primary Care Physicians: Implications for Patient Safety and Continuity of Care. JAMA 297: 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundeby, Tonje, Torunn Elin Wester, Jon Håvard Loge, Stein Kaasa, Nina Kathrine Aass, Kjersti Støen Grotmol, and Arnstein Finset. 2020. Challenges and Learning Needs for Providers of Advanced Cancer Care: Focus Group Interviews with Physicians and Nurses. Palliative Medicine Reports 1: 208–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlfatrick, Sonja. 2007. Assessing palliative care needs: Views of patients, informal carers and healthcare professionals. Journal of Advanced Nursing 57: 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, Fien, Marij Sercu, Aurélie Derycke, Lien Naert, Luc Deliens, Myriam Deveugele, and Peter Pype. 2022. Patients’ experiences of transfers between care settings in palliative care: An interview study. Annals of Palliative Medicine 11: 2830–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moback, Berit, Ruth Gerrard, Janet Campbell, Lucie Taylor, Ollie Minton, and Patrick Charles Stone. 2011. Evaluating a fast-track discharge service for patients wishing to die at home. International Journal of Palliative Nursing 17: 501–06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Gaye, Anna Collins, Caroline Brand, Michelle Gold, Carrie Lethborg, Michael Murphy, Vijaya Sundararajan, and Jennifer Philip. 2013. Palliative and supportive care needs of patients with high-grade glioma and their carers: A systematic review of qualitative literature. Patient Education and Counseling 91: 141–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morey, Trevor, Mary Scott, Stephanie Saunders, Jaymie Varenbut, Michelle Howard, Peter Tanuseputro, Colleen Webber, Tieghan Killackey, Kirsten Wentlandt, Camilla Zimmermann, and et al. 2021. Transitioning from Hospital to Palliative Care at Home: Patient and Caregiver Perceptions of Continuity of Care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 62: 233–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, Scott A. 2002. Dying of lung cancer or cardiac failure: Prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers in the community. BMJ 325: 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naylor, Mary D., Linda H. Aiken, Ellen T. Kurtzman, Danielle M. Olds, and Karen B. Hirschman. 2011. The care span: The importance of transitional care in achieving health reform. Health Affairs (Millwood) 30: 746–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, Jonas, Carl Blomberg, Georg Holgersson, Tobias Carlsson, Michael Bergqvist, and Stefan Bergström. 2017. End-of-life care: Where do cancer patients want to die? A systematic review. Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology 13: 356–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, Ai, and Fliss E. M. Murtagh. 2014. The challenges of uncertainty and interprofessional collaboration in palliative care for non-cancer patients in the community: A systematic review of views from patients, carers and health-care professionals. Palliative Medicine 28: 1081–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterveld-Vlug, M. G., B. Custers, J. Hofstede, G. A. Donker, P. M. Rijken, J. C. Korevaar, and A. L. Francke. 2019. What are essential elements of high-quality palliative care at home? an interview study among patients and relatives faced with advanced cancer. BMC Palliative Care 18: 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, Mourad, Hossam Hammady, Zbys Fedorowicz, and Ahmed Elmagarmid. 2016. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews 5: 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, Sheila A., and Jeroen Hasselaar. 2023. Exploring the Concept of Transitions in Advanced Cancer Care: The European Pal_Cycles Project. Journal of Palliative Medicine 26: 744–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabow, Michael W., Joshua M. Hauser, and Jocelia Adams. 2004. Supporting Family Caregivers at the End of Life: They Don’t Know What They Don’t Know. JAMA 291: 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocío, López, Edier Arias Rojas, Mabel Carrillo González, Sonia Carreño, Cárdenas Diana, and Olga Gómez. 2017. Experiences of patient-family caregiver dyads in palliative care during hospital-to-home transition process. International Journal of Palliative Nursing 23: 332–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, Stephanie, Marianne E. Weiss, Chris Meaney, Tieghan Killackey, Jaymie Varenbut, Emily Lovrics, Natalie Ernecoff, Amy T. Hsu, Maya Stern, Ramona Mahtani, and et al. 2021. Examining the course of transitions from hospital to home-based palliative care: A mixed methods study. Palliative Medicine 35: 1590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, Stephanie, Tieghan Killackey, Allison Kurahashi, Chris Walsh, Kirsten Wentlandt, Emily Lovrics, Mary Scott, Ramona Mahtani, Mark Bernstein, Michelle Howard, and et al. 2019. Palliative Care Transitions from Acute Care to Community-Based Care—A Systematic Review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 58: 721–34.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Clare, Nick Bosanquet, Julia Riley, and Jonathan Koffman. 2019. Loss, transition and trust: Perspectives of terminally ill patients and their oncologists when transferring care from the hospital into the community at the end of life. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 9: 346–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stajduhar, Kelli I. 2003. Examining the perspectives of family members involved in the delivery of palliative care at home. Journal of Palliative Care 19: 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stajduhar, Kelli I., Laura Funk, and Linda Outcalt. 2013. Family caregiver learning—How family caregivers learn to provide care at the end of life: A qualitative secondary analysis of four datasets. Palliative Medicine 27: 657–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhera, Javeed. 2022. Narrative reviews: Flexible, rigorous, and practical. Journal of Graduate Medical Education 14: 414–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrén, Susanne M., Britt-Inger Saveman, and Eva G. Benzein. 2006. Being a family in the midst of living and dying. Journal of Palliative Care 22: 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, Dominique, Catherine Prady, Karine Bilodeau, Nassera Touati, Maud-Christine Chouinard, Martin Fortin, Isabelle Gaboury, Jean Rodrigue, and Marie-France L’Italien. 2017. Optimizing clinical and organizational practice in cancer survivor transitions between specialized oncology and primary care teams: A realist evaluation of multiple case studies. BMC Health Services Research 17: 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Block, Lieve, Winne Ko, Guido Miccinesi, Sarah Moreels, Ge A. Donker, Bregje Onwuteaka-Philipsen, Tomas V. Alonso, Luc Deliens, and IMPACT EURO. 2016. Final transitions to place of death: Patients and families’ wishes. Journal of Public Health 39: e302–e311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatasalu, Munikumar Ramasamy, Amanda Clarke, and Joanne Atkinson. 2015. ‘Being a conduit’ between hospital and home: Stakeholders’ views and perceptions of a nurse-led palliative care discharge facilitator service in an acute hospital setting. Journal of Clinical Nursing 24: 1676–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadhwa, Deepa, Debika Burman, Nadia Swami, Gary Rodin, Christopher Lo, and Camilla Zimmermann. 2013. Quality of life and mental health in caregivers of outpatients with advanced cancer. Psycho-Oncology 22: 403–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldrop, Deborah P., Betty J. Kramer, Judith A. Skretny, Robert A. Milch, and William Finn. 2005. Final transitions: Family caregiving at the end of life. Journal of Palliative Medicine 8: 623–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, Victoria J., and J. Idris Baker. 2007. Please, I want to go home: Ethical issues raised when considering choice of place of care in palliative care. Postgraduate Medical Journal 83: 643–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Donna M., and Stephen Birch. 2018. Moving from place to place in the last year of life: A qualitative study identifying care setting transition issues and solutions in Ontario. Health & Social Care in the Community 26: 232–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabroff, K. Robin, and Youngmee Kim. 2009. Time costs associated with informal caregiving for cancer survivors. Cancer 115: 4362–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Concepts | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Transition | Community | Palliative Care | |

| PubMed | Transition Article title | Community Title/abstract | Palliative Title/abstract |

| Science Direct | Transition | Community | Palliative Care |

| Scopus | Transition Title | Community Title, abstract, key word | Palliative Title, abstract, key word |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Contain a qualitative or mixed-method study Approach the experiences and the perspectives of patients, families and healthcare professionals on the transition between care settings Provides information on barriers and facilitators to transition between care settings Full-text article Published in English Published between January 2010–January 2023 | Approach transitions in goals of care or care management Approach transitions from other care settings than from hospital to community care Non-original articles, literature reviews |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hurducas, F.; Csesznek, C.; Mosoiu, D. The Experience of Transition from Hospital to Community Care of Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Qualitative Narrative Review of Patients’, Families’ and Healthcare Professionals’ Perspectives. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050287

Hurducas F, Csesznek C, Mosoiu D. The Experience of Transition from Hospital to Community Care of Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Qualitative Narrative Review of Patients’, Families’ and Healthcare Professionals’ Perspectives. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(5):287. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050287

Chicago/Turabian StyleHurducas, Flavia, Codrina Csesznek, and Daniela Mosoiu. 2025. "The Experience of Transition from Hospital to Community Care of Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Qualitative Narrative Review of Patients’, Families’ and Healthcare Professionals’ Perspectives" Social Sciences 14, no. 5: 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050287

APA StyleHurducas, F., Csesznek, C., & Mosoiu, D. (2025). The Experience of Transition from Hospital to Community Care of Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Qualitative Narrative Review of Patients’, Families’ and Healthcare Professionals’ Perspectives. Social Sciences, 14(5), 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050287