The Impact of Virtual Exchange on College Students in the US and China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Career-Readiness Competencies

2.2. Intercultural Communication Competence (ICC)

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Context

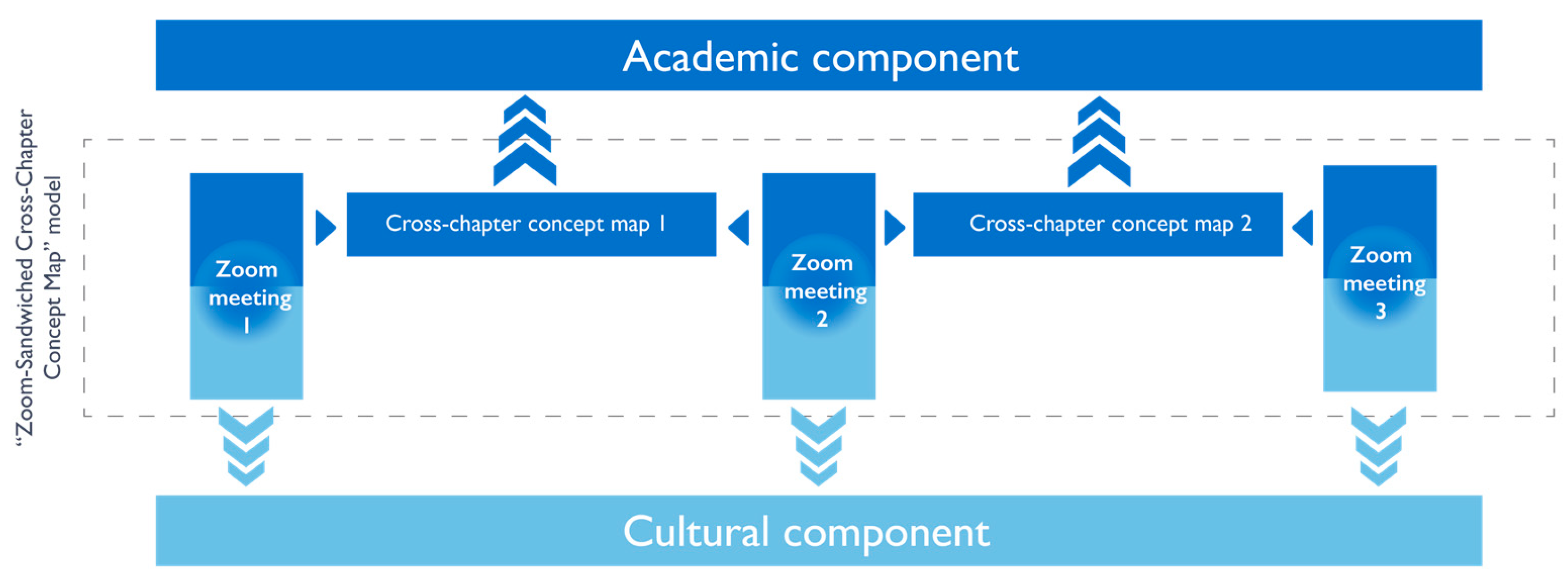

3.2. Program Design

3.3. Evaluation

4. Results

4.1. Impact of VE on Student’s ICC

4.2. Impact of VE on Students’ Confidence, Career-Readiness Competencies, and Future Plan

4.3. The Effectiveness of Zoom Meetings and the Overall VE Design Evaluation

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams-Webber, Jack R. 2001. Cognitive complexity and role relationships. Journal of Constructivist Psychology 14: 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, Dorit, and Lior Naamati-Schneider. 2021. Health management students’ self-regulation and digital concept mapping in online learning environments. BMC Medical Education 21: 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arasaratnam, Lily A. 2006. Further testing of a new model of intercultural communication competence. Communication Research Reports 23: 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasaratnam, Lily A. 2009. The Development of a New Instrument of Intercultural Communication Competence. Journal of Intercultural Communication 9: 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasaratnam, Lily A., and Marya L. Doerfel. 2005. Intercultural communication competence: Identifying key components from multicultural perspectives. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 29: 137–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryanti, Cornelia, and Desi Adhariani. 2020. Students’ perceptions and expectation gap on the skills and knowledge of accounting graduates. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business 7: 649–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azih, Nonye, and Charles A Ejeka. 2015. A critical analysis of National Board for Technical Education old and new curriculum in office technology and management for sustainable development. British Journal of Education 3: 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Baitz, Ian. 2009. Concept Mapping in the Online Learning Environment: A Proven Learning Tool is Transformed in a New Environment. International Journal of Learning 16: 285–91. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, Martyn. 2013. Intercultural competence: A distinctive hallmark of interculturalism. In Interculturalism and Multiculturalism: Similarities and Differences. Edited by Martyn Barrett. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing Strasbourg, pp. 147–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bassani, Patricia Scherer, and Ilona Buchem. 2019. Virtual exchanges in higher education: Developing intercultural skills of students across borders through online collaboration. Revista Interuniversitaria de Investigación en Tecnología Educativa 6: 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byram, Michael. 1997. Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Communicative Competence. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Guo-Ming, and William J. Starosta. 1996. Intercultural communication competence: A synthesis. In Communication Yearbook 19. Edited by Brant R. Burleson. London: Routledge, pp. 353–84. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Ling. 1996. Cognitive complexity, situational influences, and topic selection in intracultural and intercultural dyadic interactions. Communication Reports 9: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commander, Nannette Evans, Wolfgang F. Schloer, and Sara T. Cushing. 2022. Virtual exchange: A promising high-impact practice for developing intercultural effectiveness across disciplines. Journal of Virtual Exchange 5: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confederation of British Industry CBI. 2011. Building for Growth: Business Priorities for Education and Skills–Education and Skills Survey 2011. London: Confederation of British Industry. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Geng, and Sjef Van Den Berg. 1991. Testing the construct validity of intercultural effectiveness. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 15: 227–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Accordo, Cristen M. 2024. Exploring Undergraduate Student Perceptions of Career Readiness: A Survey Methodology Approach. Doctoral dissertation, Molloy University, Rockville Centre, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff, Darla K. 2004. The Identification and Assessment of Intercultural Competence as a Student Outcome of International Education at Institutions of Higher Education in the United States. Doctoral dissertation, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff, Darla K. 2006. Identification and Assessment of Intercultural Competence as a Student Outcome of Internationalization. Journal of Studies in International Education 10: 241–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deardorff, Darla K. 2009. The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- EVOLVE Project Team. 2020. The Impact of Virtual Exchange on Student Learning in Higher Education: EVOLVE Project Report. Chicago: EVOLVE Project Team. [Google Scholar]

- Fantini, Alvino, and Aqeel Tirmizi. 2006. Exploring and Assessing Intercultural Competence. Brattleboro: World Learning Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Fukkink, Ruben, Rochelle Helms, Odette Spee, Arantza Mongelos, Kari Bratland, and Rikke Pedersen. 2024. Pedagogical Dimensions and Intercultural Learning Outcomes of COIL: A Review of Studies Published Between 2013–2022. Journal of Studies in International Education 28: 761–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés, Pilar, and Robert O’Dowd. 2021. Upscaling virtual exchange in university education: Moving from innovative classroom practice to regional governmental policy. Journal of Studies in International Education 25: 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, Mohsen. 2023. Implementing NACE competencies in LEED Lab to prepare a career-ready workforce. Paper presented at the 2023 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Baltimore, MD, USA, June 25. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, Richard L., Leah Wolfeld, Brigitte K. Armon, Joseph Rios, and Ou Lydia Liu. 2016. Assessing intercultural competence in higher education: Existing research and future directions. ETS Research Report Series 2016: 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, Francesca, and Sarah Guth. 2012. Open intercultural dialogue: Educator perspectives. Journal of E-learning and Knowledge Society 8: 129–39. [Google Scholar]

- Inganah, Siti, Nopia Rizki, Choirudin Choirudin, Syed Muhammad Yousaf Farooq, and Novi Susanti. 2023. Integration of Islamic values, mathematics, and career readiness com-petencies of prospective teachers in Islamic universities. Delta-Phi: Jurnal Pendidikan Matematika 1: 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, Susan L., Cathy L. Hennen-Floyd, and Kathleen M. Farrell. 1990. Cognitive complexity and verbal response mode use in discussion. Communication Quarterly 38: 350–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Yulong. 2013. Cultivating student global competence: A pilot experimental study. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education 11: 125–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Wei, David Sulz, and Gavin Palmer. 2022. The Smell, the Emotion, and the Lebowski Shock: What Virtual Education Abroad Cannot Do? Journal of Comparative and International Higher Education 14: 112–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lörz, Markus, Nicolai Netz, and Heiko Quast. 2016. Why do students from underprivileged families less often intend to study abroad? Higher Education 72: 153–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Jiali, and David Jamieson-Drake. 2015. Predictors of study abroad intent, participation, and college outcomes. Research in Higher Education 56: 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Association of Colleges and Employers NACE. 2021. Available online: https://www.naceweb.org/career-readiness/competencies/career-readiness-defined (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Newell, MiKayla J., and Paul N. Ulrich. 2022. Competent and employed: STEM alumni perspectives on undergraduate research and NACE career-readiness competencies. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability 13: 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nodine, Thad R. 2016. How did we get here? A brief history of competency-based higher education in the United States. The Journal of Competency-Based Education 1: 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dowd, Robert. 2020. A transnational model of virtual exchange for global citizenship education. Language Teaching 53: 477–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dowd, Robert. 2021. What do students learn in virtual exchange? A qualitative content analysis of learning outcomes across multiple exchanges. International Journal of Educational Research 109: 101804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dowd, Robert, and Tim Lewis, eds. 2016. Online Intercultural Exchange: Policy, Pedagogy, Practice. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Portalla, Tamra, and Guo-Ming Chen. 2010. The development and validation of the intercultural effectiveness scale. Intercultural Communication Studies 19: 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Prikshat, Verma, Sanjeev Kumar, and Alan Nankervis. 2019. Work-readiness integrated competence model: Conceptualisation and scale development. Education+ Training 61: 568–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinsley, Roslyn T., and Krisztian Baranyai. 2015. STEM Skills in the Workforce: What Do Employers Want? Brisbane: Office of the Chief Scientist. [Google Scholar]

- Rachmawati, Dian, Sheerad Sahid, Mohd Izwan Mahmud, and Nor Aishah Buang. 2024. Enhancing student career readiness: A two-decade systematic. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education 13: 1301–10. [Google Scholar]

- Redmond, Mark V. 1985. The relationship between perceived communication competence and perceived empathy. Communications Monographs 52: 377–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sercu, Lies. 2004. Assessing intercultural competence: A framework for systematic test development in foreign language education and beyond. Intercultural Education 15: 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens Initiative. 2020. Virtual Exchange Impact and Learning Report. Aspen: Aspen Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens Initiative. 2023. Virtual Exchange Impact and Learning Report. Aspen: Aspen Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Martyn. 2012. Joined up thinking? Evaluating the use of concept-mapping to develop complex system learning. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 37: 349–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trends in U.S. Study Abroad. 2020. NAFSA: Association of International Educators. September 15. Available online: https://www.nafsa.org/policy-and-advocacy/policy-resources/trends-us-study-abroad (accessed on 2 December 2023).

- Tubaundule, G., N. Sisinyize, N. Sihela, M. Katijere, and B. Hilarious. 2024. Integrating Career Readiness Competencies into Vocational Curriculum for Enhanced Graduate Employability: A Case Study of Selected Trade Areas in Namibia. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management (IJSRM) 12: 5783–93. [Google Scholar]

- Vásquez, Heydi Tananta. 2022. Higher Education in Pandemic Times. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice 22: 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zak, Anna. 2021. An integrative review of literature: Virtual exchange models, learning outcomes, and programmatic insights. Journal of Virtual Exchange 4: 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Hongmei, Chad Marchong, and Yanju Li. 2024. Tab-Meta Key: A Model for Exam Review. Journal of College Science Teaching 53: 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Hongmei, Yanju Li, and Martha Fulk. 2023. Zoom-sandwiched cross-chapter concept map: A novel model to optimize a concept map project in online STEM courses. Advances in Physiology Education 47: 326–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Yali, Hongmei Zhang, and N. Commander. 2023. Promoting Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Global Education Through Virtual Exchange. Global Inclusion, 20–22. [Google Scholar]

| ICC Dimensions | ICC Items | ICC Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Affective | 1 | I feel that people from other cultures have many valuable things to teach me. |

| 2 | I feel more comfortable with people from my own culture than with people from other cultures. | |

| 3 | I usually feel closer to people who are from my own culture because I can relate to them better. | |

| 4 | I feel more comfortable with people who are open to people from other cultures than people who are not. | |

| Behavioral | 5 | Most of my close friends are from other cultures. |

| 6 | Most of my friends are from my own culture. | |

| 7 | I usually look for opportunities to interact with people from other cultures. | |

| Cognitive | 8 | I often find it difficult to differentiate between similar cultures (Ex: Asians, Europeans, Africans, etc.) |

| 9 | I find it easier to categorize people based on their cultural identity than their personality. | |

| 10 | I often notice similarities in personality between people who belong to completely different cultures. |

| Questions No. | Questions |

|---|---|

| 1 | Before taking the BIOL 2107 course, did you have any international study experience (e.g., participating in study abroad program)? |

| 2 | Before taking the BIOL 2107 course, did you have any experience with interacting with people from different cultures? |

| 3 | What was your confidence level when interacting with culturally different people before this VE experience? |

| 4 | What is your confidence level when interacting with culturally different people after this VE experience? |

| 5 | To what extent did the VE improve your overall career-readiness competencies? (https://www.naceweb.org/career-readiness/competencies/career-readiness-defined/; accessed on 20 August 2021)? |

| 6 | Did the VE impact any of your specific career-readiness competencies? Please comment on which ones and how (https://www.naceweb.org/career-readiness/competencies/career-readiness-defined/; accessed on 20 August 2021; also see the NACE document uploaded) |

| 7 | To what extent does the VE experience influence your future study plan. |

| 8 | Overall, to what extent do you think the Zoom meetings helped you exchange culture with your partners? |

| 9 | What have you discussed most during the 1st Zoom meetings (spend most time on)? |

| 10 | What do you discuss most during the 2nd Zoom meetings? |

| 11 | What do you discuss most during the 3rd Zoom meetings? |

| 12 | Overall, to what extent are you satisfied with the incorporation of the VE program in the BIOL 2107 course? |

| 13 | Would you recommend the professor continue incorporating the VE program in future classes? |

| Dimension | US (n = 48) | Chinese (n = 61) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Survey M (SD) | Post-Survey M (SD) | p Value | Pre-Survey M (SD) | Post-Survey M (SD) | p Value | |

| Affect | 3.75 (0.53) | 3.66 (0.54) | 0.24 | 3.56 (0.53) | 3.48 (0.62) | 0.35 |

| Behavior | 3.69 (0.79) | 3.60 (0.85) | 0.24 | 2.56 (0.74) | 2.94 (0.66) | <0.001 |

| Cognition | 4.01 (0.56) | 3.91 (0.58) | 0.33 | 3.87 (0.63) | 3.83 (0.77) | 0.72 |

| Overall | 3.81 (0.44) | 3.72 (0.50) | 0.09 | 3.35 (0.48) | 3.42 (0.54) | 0.33 |

| Question No. | Scale | GSU Students Sample Size n (Percentage) Total n = 50 | SWJTU Students Sample Size n (Percentage) Total n = 61 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Yes | 9 (18.0%) | 15 (24.6%) |

| No | 41 (82.0%) | 46 (75.4%) | |

| Q2 | Yes | 47 (94.0%) | 54 (88.5%) |

| No | 3 (6.0%) | 7 (11.5%) | |

| Q3 | Not confident at all | 3 (6.0%) | 7 (11.5%) |

| Slightly confident | 7 (14.0%) | 29 (47.5%) | |

| Moderately confident | 29 (58.0%) | 17 (27.9%) | |

| Very confident | 7 (14.0%) | 5 (8.2%) | |

| Extremely confident | 4 (8.0%) | 3 (4.9%) | |

| Q4 | Not confident at all | 2 (4.0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Slightly confident | 3 (6.0%) | 3 (4.9%) | |

| Moderately confident | 14 (28.0%) | 32 (52.5%) | |

| Very confident | 19 (38.0%) | 21 (34.4%) | |

| Extremely confident | 11 (22.0%) | 5 (8.2%) | |

| Q5 | None at all | 3 (6.0%) | 0 (0%) |

| A little | 13 (26.0%) | 2 (3.3%) | |

| A moderate amount | 18 (36.0%) | 26 (42.6%) | |

| A lot | 11 (22.0%) | 27 (44.3%) | |

| A great deal | 5 (10.0%) | 6 (9.8%) | |

| Q7 | None at all | 8 (16.0%) | 1 (1.6%) |

| A little | 15 (30.0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| A moderate amount | 15 (30.0%) | 26 (42.6%) | |

| A lot | 7 (14.0%) | 26 (42.6%) | |

| A great deal | 5 (10.0%) | 8 (13.1%) | |

| Q8 | None at all | 2 (4.0%) | 0 (0%) |

| A little | 7 (14.0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| A moderate amount | 19 (38.0%) | 10 (16.4%) | |

| A lot | 15 (30.0%) | 37 (60.7%) | |

| A great deal | 7 (14.0%) | 14 (23.0%) | |

| Q9 | Introduction | 35 (70.0%) | 45 (73.8%) |

| Social media | 6 (12.0%) | 8 (13.1%) | |

| Concept map project | 8 (16.0%) | 8 (13.1%) | |

| I did not attend | 1 (2.0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Q10 | Career-readiness competencies | 0 (0%) | 3 (4.9%) |

| Festivals | 27 (54.0%) | 32 (52.5%) | |

| Concept map project | 22 (44.0%) | 26 (42.6%) | |

| I did not attend | 1 (2.0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Q11 | Future plan | 20 (40.0%) | 31 (50.8%) |

| Food | 20 (40.0%) | 20 (32.8%) | |

| Concept map project | 9 (18.0%) | 10 (16.4%) | |

| I did not attend | 1 (2.0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Q12 | Extremely dissatisfied | 4 (8.0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 6 (12.0%) | 1 (1.6%) | |

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 10 (20.0%) | 10 (16.4%) | |

| Somewhat satisfied | 22 (44.0%) | 29 (47.5%) | |

| Extremely satisfied | 8 (16.0%) | 21 (34.4%) | |

| Q13 | Yes | 35 (70.0%) | 58 (95.1%) |

| No | 15 (30.0%) | 3 (4.9%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, H.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Marchong, C.; Cotter, D.; Zhou, X.; Huang, X. The Impact of Virtual Exchange on College Students in the US and China. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050281

Zhang H, Wu J, Li Y, Marchong C, Cotter D, Zhou X, Huang X. The Impact of Virtual Exchange on College Students in the US and China. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(5):281. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050281

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Hongmei, Jian Wu, Yanju Li, Chad Marchong, David Cotter, Xianli Zhou, and Xinhe Huang. 2025. "The Impact of Virtual Exchange on College Students in the US and China" Social Sciences 14, no. 5: 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050281

APA StyleZhang, H., Wu, J., Li, Y., Marchong, C., Cotter, D., Zhou, X., & Huang, X. (2025). The Impact of Virtual Exchange on College Students in the US and China. Social Sciences, 14(5), 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050281