6.1. Educators’ Growing Breadth of Responsibilities

6.1.1. Provisioning Basic Needs: “I’m a Cook…and Counselor… the Teacher Aspect Is at the Very End of What I Do”

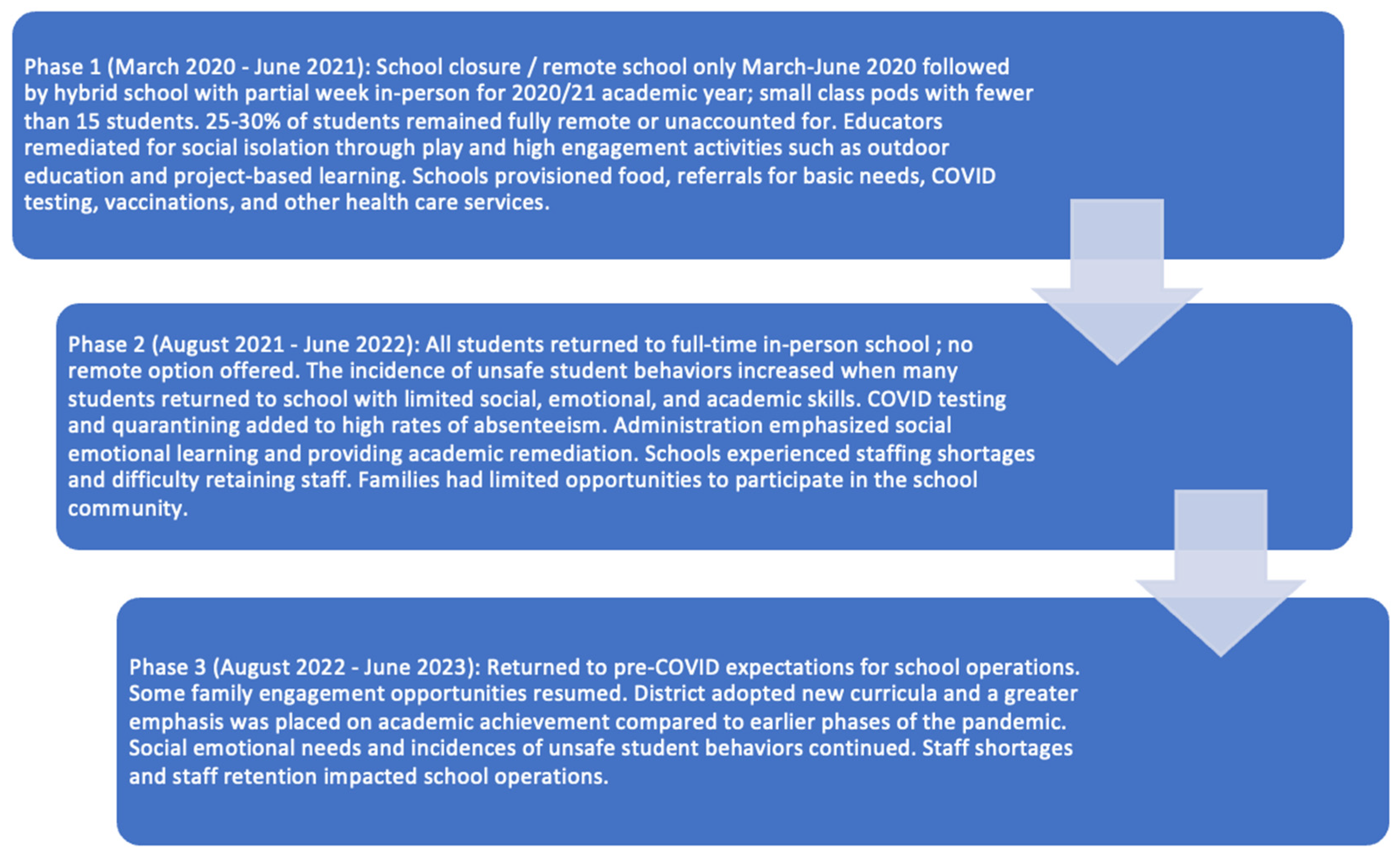

The role of schools as a gateway for families to have their basic needs met grew throughout the pandemic. This created a problematic dynamic for educators who were taking on responsibilities that would have previously fallen outside their roles. All teachers in this study shared feelings of frustration, inadequacy, or guilt for not having the skills, resources, and connections to ensure that their students were safe, sheltered, clothed, fed, and able to access physical and mental health care services. Despite the limited capacity of schools to fill these needs, 14 participants felt unable to retreat from this role and expressed their despondency when their students and families could not access the necessary support. For example, Kai, an upper elementary teacher, explained,

Asking school staff to step into the gaps that we’re not qualified for [social worker, mental health worker, etc.] takes us away from teaching and requires brain power that could be put to other things, and that can get really dangerous—to be that far from what you feel qualified to do.

Devin, who served in a leadership role, emphasized that school staff were now responsible for, “feeding kids, getting them appropriate clothing or footwear, making sure they have housing, supporting their parents or guardians or their grandparents in daily life tasks and also in supporting their children… so they [students] can access their learning”. The period of school closure and partial reopening during Phase One set the stage for what became an often untenable situation for educators.

Wendy, an early elementary teacher, shared, “school became a place where families got everything… we’re providing meals, COVID tests, driving things [supplies] to you… an endless list of things that were the job of school and the teacher with no limits whatsoever”. Twelve participants felt that schools had assumed too much responsibility, and a plan needed to be put in place to step back from this role. Gail, a third-grade teacher explained, “we took on and kept on doing all these things and now there’s an expectation”. By extension, Winny added, “the more you give, the more that is expected”. Fourteen participants called for a reevaluation of the school’s role within the larger community.

6.1.2. Remediating Following School Closure: “Priority Was for the Kids to Feel Connected and Safe”

At the start of Phase Two, when all students returned to full-time in-person school in August 2021, there was a disconnect between resuming school as it functioned prior to the pandemic and the needs of many students. All 16 participants reported that due to social isolation and remote learning, many students were unable to access academic content designed for their grade level. Consequently, focusing on academic instruction no longer responded to many students’ needs. Instead, emotional and physical safety had to be ensured before students could engage in academic learning. While social–emotional learning had always been integral to the elementary school experience, it became central as students returned to school with more limited social skills, often exacerbated by deteriorated physical and mental health.

Educators were thrust into a situation where their previous role teaching academic content had to yield to the students’ stunted ability to engage in academic learning. There was a mismatch between students’ readiness for school and the schools’ readiness for students. Twenty-five to 30 percent of students had not attended in-person school for up to 17 months, with limited opportunities for in-person social interaction during the first phase of the pandemic. While some families were able to establish conditions for their children to continue to learn through remote platforms, half of the participants reported that many students minimally participated in remote schooling. Twelve educators participating in this study remembered Phase One as a time when boundaries between their personal and professional lives dissolved and norms around family–teacher interactions shifted. While some students became unreachable, other families interacted with their children’s teachers more frequently. Sam recalled,

There were very few boundaries. Parents were texting and emailing at all hours and expecting a timely response. Many parents were actually attending classes in the background, as kids were often in common spaces during class. It was challenging, but also seemed necessary. The kids that were the most successful were the ones who had parents that were paying attention.

At that point, no one knew the duration of school closures, and in retrospect, half of the participants lamented their decisions to remove barriers between their professional and personal lives. Nine participants shared that frequent contact with families outside of school hours led to increased work-related stress, impacting their personal lives. However, a greater level of engagement between home and school also had positive results for families who were involved in their children’s education during Phase One.

6.1.3. Renegotiating Relationships Between Home and School: “A Foot in Both Worlds”

The blurring of roles between home and school changed the nature of both institutions. For example, Wendy, an early elementary teacher, explained the experience of teaching during the pandemic as having “a foot in both worlds” while she also managed her own daughter’s schooling from home. Both worlds can be understood as the dissonance created when the roles between home and school were obscured during the pandemic.

Half of the participants remembered a time, during Phase One, when deeper relationships with students translated to closer family communications. With fewer students in each class, educators could better communicate with individual households, and the need for more support from school-based staff for families to facilitate remote instruction translated to a higher level of family engagement. While some educators felt that, in hindsight, this level of engagement with families became expected and unsustainable, the strengthening of ties between home and school mostly benefited students, educators, and families. Sam, an upper elementary teacher, had hoped to maintain this level of connection with families in Phase Two when returning to full-time in-person school with larger class sizes, but he has not been able to sustain this level of engagement. He attributed this to the time-consuming nature of reaching out to individual households and the end of remote learning. Families no longer needed the frequent contact with educators to access school, but with fewer interactions, the connection between home and school deteriorated.

Participants also shared their experiences with the shifting of roles between home and school. Ollie, a fourth-grade teacher, reflected on the growing number of families who no longer fulfilled parental responsibilities commonly accepted before the pandemic. According to Ollie, the relationship with families has significantly changed, and “I think the parents just expect us to do everything in a way that when I started teaching, they didn’t as much”. Ten participants shared stories of having to track down paperwork or call families when signed permission forms were never returned to school. A kindergarten teacher shared that she had multiple students whose parents never opened and checked their backpacks. A first-grade teacher reported that she had never met or spoken with some of the parents of her students despite multiple attempts at communication. These accounts demonstrate how the connection between home and school fluctuated throughout the pandemic.

Communication between home and school varied depending on family circumstances and the phase of the pandemic. The gap widened between those students who engaged in school and those who were absent. Sam shared,

The learning gap was increased by the pandemic. Some parents were able to create time, space, and prioritize learning, [and they] worked to hold their kids accountable, [but] many kids were left to manage the situation on their own. Very few elementary kids are self-motivated and organized enough to pull off online learning independently. The gap between the haves and the have-nots was laid bare.

Kai shared how the role of technology made plain this inequity, “During the remote time, I would have kids do 700 math problems [using an online platform]… and kids who did 20, and so the gap grew”. This gap continued to grow while in-person school remained optional, and the extent to which some students returned lacking foundational academic skills contributed to an unstable transition for many. When remote schooling was no longer available, students who had minimally accessed their education returned to in-person schooling with limited academic and social skills. Wendy, an early elementary teacher, explained, “School is what you do, not what you hear”, but when students first returned to school, they were expected to listen to or read instructions, with limited options for play and interaction due to social distancing guidelines. As a result, the incidence of unsafe and disruptive behavior, characterized by physical and verbal outbursts, increased when full-time in-person schooling resumed.

6.1.4. Reacting to Students’ Social and Emotional Needs: “Big Things That Feel Urgent or Intense or Scary Happen Weekly”

All teachers interviewed adjusted their practice in response to students’ changing needs. For example, more time was allocated to community building and social skill development when compared to pre-pandemic times. However, all participants reported a lag in developing a systems-level approach to managing student behaviors. During Phase One, for students who opted for part-time in-person learning, the focus was on ensuring students felt safe and happy to be at school. In Phase Two, schools became overwhelmed by the number of students who had profound academic and social needs. Pre-pandemic systems for addressing harmful behaviors were no longer sufficient, resulting in frustration for educators. Wendy explained that because “we don’t have systems [for behavior], we are reacting differently every time”. This lack of consistency created school atmospheres where expectations and consequences for student behavior were unclear.

In response to students exhibiting dysregulated emotions, educators expended more of their time and energy creating clear behavior support systems within their classrooms. Gail designated an area for students to reset when they were feeling overwhelmed. This was a space within the classroom where students could retreat from the group and quietly process their emotions by drawing, playing with fidgets, or engaging in other relaxation techniques. While prior to the pandemic, this type of space might have been needed by a few students in the class, Gail shared that the reset space was used by the majority of students. In reaction to students’ social and emotional needs, Sam devoted more energy to creating a self-contained classroom environment of predictable routines and explicitly stated and reinforced behavior expectations. He explained, “I don’t think we do kids any favors when we are too soft. Kids need clear boundaries”. Sam further described his students as “now needing more help with social skills and self-regulation tools… kids are emotionally in rough shape”. Gail agreed and described her role as “helping students regulate their emotions and help them understand how to work better together”. Overall, nine teachers described redesigning their classrooms or adjusting their pedagogical approach to better respond to students’ social–emotional needs.

Without clarity on how to prioritize the range of student needs, teachers experienced tension between their role to provide educational opportunities for all learners and the urgent attention demanded by unsafe student behaviors. Feeling less like a teacher and more like a behavior manager was a major shift in roles for many educators during the second and current phases of the pandemic. Kai shared, “There has been a lot of burnout. There has been a lot of turnover because nobody knew what to do about behaviors, everybody is scrambling, nobody felt supported, and this is hard”. This struggle was recognized by all participants.

6.2. Challenges with Staffing

6.2.1. Educator Shortages and Training: “This No Longer Feels Like a Desirable Job to Have”

Staffing shortages have plagued public schools since the onset of the pandemic. The number of qualified applicants to fill positions dropped off precipitously since schools fully reopened in Phase Two. Devin, who is responsible for hiring, reflected, “We used to get 100 applicants for a classroom job. And now I’ve had a job open since April [five months] with no applicants”. This stark reality of the job market was exacerbated by deteriorating work conditions for school-based personnel. Wendy continued, “This no longer feels like a desirable job to have. Paras [support staff] don’t get paid enough. Teachers are leaving this profession because of the [student] behaviors”.

In addition to unfilled positions, during Phases Two and Three, there was also a lack of training or expertise among existing staff to meet the new demands of their positions. Feeling unqualified, unsupported, or unequipped to successfully fulfill the duties of one’s job had led to the deterioration of morale.

During Phase Three, educational leaders focused professional development efforts on meeting the emergent training needs of staff. Outside experts on teaching executive functioning, or the skills students need to plan and meet goals, were brought in, and behavior interventionists were hired to help educators become more successful in their jobs. Half of the participants welcomed these efforts and felt that their concerns had been heard. However, others relayed that training was not enough given the day-to-day reality. Experts and behavior consultants came in, but according to Bess,

Being told how to do something and actually doing it are two different things… I’m already doing all the things they are telling me. I’m not a first-year teacher. I feel insulted. Their goal is to help me … but the things I’ve been given, I already know how to do. It’s not their fault, but it’s not enough… I’m being given support, but it’s not enough support.

The lack of qualified staff to fill essential roles within the school impacted the existing personnel’s relationship with their work. Half of the participants, who formerly intended to be career educators, shared reservations about staying in their jobs due to staffing shortages or lacking the skills to feel successful in their roles.

6.2.2. Teacher Retention and Commitment: “If We Sold Our House, Could I Stop Working?”

The lack of adequately trained staff and the rise in unsafe student behaviors were mutually reinforcing. All participants in this study shared experiences of colleagues leaving the profession. Without ample staff to meet students’ social, emotional, and academic needs, individuals were more likely to react in frustration. This was compounded by the hiring of new teachers who attended teacher training programs during remote instruction, creating a mismatch between their practicum experiences and the realities in their classrooms. Devin shared, “Student teachers that have become teachers never got real-life practice managing a classroom”. Subsequently, the need for mentoring and behavioral staff to support teachers had increased while the availability of professionals with expertise in these areas had become more limited. This cycle impacted staff retention and commitment to persevering in their jobs.

Coming to work every day in the face of feeling unprepared or unqualified to perform one’s job well eroded confidence and job satisfaction for many participants. Keeley, a school leader, reported that nearly half the school-based staff turned over in the past four years. Charlie, who is still early in their career, explained that teachers who have been here through the pandemic, “They’re exhausted. They are burned out by behavior issues. They’re doing all they can, and some kids are not getting what they need and it’s exhausting… they can’t give anything else, so people step away and do something different”. Wendy described Phase Two as a time when she considered leaving her teaching job because of work-related stress. She recounted conversations she had with her spouse,

If we sold our house, could I stop working? I’ve used every sick day, my bank account is empty… we’ve given grace to the community at large, we’re gentle and careful with families, but that grace has not been extended to staff.

Three-quarters of the participants shared this sense of despair and resignation. Thomas echoed this sentiment by explaining, “I really have to leave in order to be in a situation where I’m feeling heard… the longer it [lack of staff and support] goes on, the more I think that’s probably what has to happen”. Gail also lamented that “being here in a public school system is really, really hard right now because I feel like I’m taking a lot of grief, and I don’t have any wins”. The other quarter of the participants did not feel that leaving their positions was a viable option and developed systems of support that kept them engaged in their work.

6.2.3. Lack of Staff Management: “Why Don’t We Have Equity Among the Staff?”

With staff shortages came an increased workload for those who remained in school. In Phase Three, teachers were assigned recess and lunch duties, whereas there had formerly been sufficient support staff to provide coverage during these times. Administrators responded to the increasing incidence of unsafe student behavior by requiring certified teachers to supervise students during non-academic time. During these duties, teachers were stationed in the lunchroom or playground to oversee students, help ensure safe environments, and mediate disputes. Thirteen participants shared feelings that workloads were not shared equitably.

In addition to the perception of inequitable workloads, half of the participants also noted a lack of accountability among staff. Some showed up for work every day, coming early, often staying late. Half of the participants relayed stories of working on weekends and after hours. Three educators expressed resentment towards colleagues who do not devote as much time to their work, and felt administrators were not holding employees accountable to their contractual obligations. One teacher expressed frustration by sharing, “I watch staff stroll in at 8:10 a.m. and stroll out at 2:50 p.m. It creates a lot of bad feelings”. Seeing colleagues who are working significantly fewer hours and who are not being held accountable for their contractual commitments impacted staff morale. From an administrative standpoint, one principal shared her frustration with her staff’s perception of her role,

A lot of folks think that I’m hiding in my office with the door shut… a lot of people don’t know what I’m doing… I’m in more meetings than ever, and it makes me less visible to staff, which has been a problem.

The lack of equity and management of staff had impacted the school culture. School administrators were required to participate in more closed-door meetings and had fewer opportunities to experience firsthand how their staff members’ roles had changed and grown. Subsequently, directives were often perceived as out of touch with the day-to-day realities of the educators who were working most closely with students.

6.2.4. Educator Allocation and Morale: “It’s Not Enough Support”

Educator morale was impacted by how the available staff were allocated in the school. Participants explained that classrooms with the greatest behavior challenges received the most support. By allocating support staff to students and classrooms with the most behavioral needs, teachers were left alone to provide a range of instruction for students with various levels of academic ability and background knowledge. Of the 16 participants, 9 shared stories of mental or physical illness that they attributed to exhaustion from workplace demands. For example, Wendy shared her experience of deliberately dehydrating herself because, for six consecutive weeks, she had no other adult support in her classroom, so she could not leave to go to the restroom. Another classroom teacher shared the physical toll placed on her by the demands of her job when she was sick for over three weeks, missed two weeks of school, and was unable to get out of bed or eat for twelve days.

Some educators took positions at other schools in hopes of finding more functional educational settings. Wendy explained that several of her colleagues had taken positions at schools with strong leadership and explicit expectations for students, families, and staff alike. Casey also dreamed of working in that type of environment and said, “It would be incredible if we had a mission and vision statement for our work together”. Sam, a veteran classroom teacher who had weathered the pandemic relatively well, felt “there are a lot of disgruntled staff members. People don’t feel inspired, share a vision at a school or district level”. While Sam received the support he needed, he recognized the struggles of his colleagues and the overall deterioration of school culture. Despite this, Sam explained his decision to stay because “I love the kids, and I love the team, so I’m not sure how much leadership matters”. Marin felt differently and expressed her wish for “our administrators to have the wherewithal to identify a priority and articulate that”. In addition to impacting the retention, recruitment, and allocation of adequately trained staff, the lack of a clear academic vision and educational priorities has impacted educators’ morale.

6.3. Competing and Conflicting Demands: “When Everything Is a Priority, Nothing Is a Priority”

6.3.1. Adopting New Curricula

The schools in this study are part of a district that adopted three new curricula in the areas of language arts, math, and social–emotional learning (SEL) since Phase Two. The district’s decision to adopt a new language arts curriculum was made after dropping a previous literacy curriculum that had only been in use for a few years. With pandemic relief funds and feelings of dissatisfaction with the previous (but still new) literacy curriculum, administrators made a centralized decision to purchase yet another literacy curriculum. Nearly simultaneously, a new math curriculum was also purchased by the district. Recognizing the strain that two new core curricula would place on teachers, staff were given a choice about which curriculum to pilot and which one to fully implement during Phases Two and Three. At the start of the 2023–2024 school year, it was expected that both the new math and language arts curricula would be in use. Also, in response to the increase in unsafe student behavior, an SEL curriculum was introduced in Phase Three. Reflecting on the number of changes to curricula over the past few years, Winny shared, “I feel like as a district, we change things too quickly. We don’t even have enough time to see if what we are doing is working, and then we change it again”. This idea was reinforced by Carol, who explained, “With new curriculums… let’s not bring in something new, let’s do with what we know and let’s just take a breath and take two steps back”.

Despite resistance to the new academic curricula, two-thirds of the participants in this study were encouraged to see SEL receiving the focus that they felt was needed. Bess, an early elementary teacher, shared, “SEL is a passion of mine. I like reading about brain science. I feel like I have invested my own time into learning about those things”, and having an SEL curriculum legitimized the independent work Bess had done throughout her career. Kai, who teaches older students, felt the SEL curriculum was helpful for giving students a common language to talk about emotions across grade levels. However, the main critique centered on the idea that SEL can be handled as a separate content area. All participants felt that good teachers integrate SEL throughout the day, and according to Bess, SEL should be “built into every lesson. SEL is not its own entity; it is across everything you teach”.

Out of all the participants, none of the classroom teachers felt sufficiently supported and successful in adopting the new curricula. Carol, who is a special educator, explained that the teachers who were best adapting to the new curricular demands were the ones who, “have been able to take a step back—we’re just going to do this part or we’re just going to do this piece and that’s okay”. Without accountability and oversight in place by administrators to ensure that the curricula are being taught with fidelity, many educators relied on this approach to manage the volume of new material and programs. Winny confided that “there’s not a lot of oversight, nobody comes in really and checks on you to see what you are doing. That works to my advantage”. Educators were trying to do what was being asked and expected within the reality of their students’ needs and limited time.

6.3.2. Feeling Unable to Meet Diverse Student Needs: “Growing… Getting What You Need… Should Be for Everyone”

The range of students’ needs required an overhaul of schedules and staff allocations during Phases Two and Three, with unanticipated consequences. When students and staff returned to full-time in-person schooling in Phase Two, building administrators worked with staff to determine how academic and behavior support services would fit into student schedules. This was also complicated by the staffing shortage and larger caseloads for interventionists (professional staff who intervene to provide specialized instruction, academic or behavior supports within or outside the general classroom setting). The lack of cohesion throughout the day and the need for more specialists to work with students were stark contrasts to Phase One. In contrast to Phase One, when alternative educational approaches such as student-led and project-based learning, as well as outdoor and place-based education, were widely practiced, in Phase Three, this became less feasible due to curricular demands and fewer uninterrupted blocks of time. Sam further explained,

With so many kids in need of specialized services, there is a lot of coming and going. Last year [Phase Three], I had a single 40-minute block in my entire week in which I had my full class. It’s a challenge to schedule things because at every point, you’re deciding who can afford to miss what. The momentum required for true project-based learning and following students’ lead is missing.

Nine participants felt that more enrichment opportunities should be provided for their students because teachers could not assume additional responsibilities. Thomas, who teaches upper elementary, explained, “We don’t have an enrichment teacher… those kids, I’m told, oh, they’re fine. I said, ‘Would that be fair to you?’” Five teachers felt that all students benefit from enrichment opportunities, but unsafe behavior was the main obstacle to offering students learning opportunities beyond the classroom setting.

Despite the challenges, educators found creative ways to extend student learning while holding onto teaching practices that reflected their own passions, strengths, and priorities. Kai shared their experience of “trying a new math [practice] this year that is more collaborative and kids hanging out with other people while doing a pretty focused push on academics- finding that balance”. Sam remembered one of the most joyous times of this current school year when a group of teachers played an impromptu soccer game with their students to model good sportsmanship. He laughed, “It felt authentic and real, and it was true modeling”. Sam surmised that the value came from where the idea originated—from the teachers who gave up their recess time to provide a meaningful and fun learning experience for their students rather than a top-down mandate.

6.3.3. Frustration with Data Management, Standards, and Reporting: “You’re Just Doing These Monotonous Tasks for No Reason”

Systems for managing data, changing standards, and misaligned reporting expectations were areas of frustration shared by half of the educators. Eight participants spoke of the lack of cohesive systems for collecting, storing, utilizing, and reporting data. Since Phase Two, students had been assessed using standardized measures multiple times throughout the school year, but the data did not necessarily reflect what was being taught in the curricula, nor were they consistently aligned with grade-level standards and reporting requirements. One-quarter of the participants discussed this disconnect in relation to the prioritized standards developed during Phase One. Through a collective process, educators met with administrators to determine where to focus academic instruction with more limited contact hours with students. Marin described this process as unifying while creating a cohesive outcome. Since Phase Two, priority standards had given way to a confusing and conflicting array of initiatives that often did not align with districtwide reporting practices. The importance placed on data measuring academic progress also conflicted with messages from leadership to prioritize social–emotional learning and alternative educational approaches. Marin shared that the “importance of play [in early elementary] is completely contradicted when we go to the data meetings”. Marin further lamented that this contradiction is rarely discussed head-on because “everyone is so polite”. The process for collecting, storing, and utilizing student data was an area of frustration for half of the participants.

Another common response to the new curricula was in reaction to the academic standards. Since the curricula are designed for a specific grade level, there is an expectation that the students have the skills and background knowledge to access the content at that level. Coming out of the pandemic, fewer than half of the students were considered proficient at grade-level standards for reading and math, which meant they were unable to access grade-level curricula without significant support. Bess, who teaches second graders, shared,

I think we need to shift our thinking academically as far as these kids that missed these chunks of time and learning, but no one is giving us a pause. Everyone is saying show up and keep going and… we are [but] there are still big gaps in kids’ learning and it’s not reflected in the curricula and assessments… They need to shift because if not, I’m referring half my class for an IEP [individual education plan].

Other teachers agreed that the expectations of academic progress should reflect the breadth of skills within a grade level.

Gail, who teaches a younger grade, appreciated the flexibility available to students to “show what they know in different ways”. This allowed Gail to be more creative with student assessments, including the use of more hands-on and less text-based learning for students with limited reading and writing skills. Interestingly, these alternative assessments, while an acceptable measure of students’ learning earlier in the pandemic, no longer necessarily aligned with the assessments in the newly adopted curricula, thus requiring more work on the part of the teacher to create such alternatives. Overall, half of the participants in teaching roles shared frustration with the data management, standards, and reporting systems that complicated rather than streamlined their work.

6.3.4. Navigating Socio-Political Forces: “I Have a BLM and Pride Flag. I Don’t Know If I Could Teach Anywhere Else”

The public perception of educators’ work fluctuated over the course of the pandemic. During Phase One, teachers were regarded as heroes as the public recognized the importance of schools and the services they provided. Sam claimed that one of the main takeaways from the pandemic was that “school really, really matters”. Nonetheless, political divisiveness stoked by pandemic restrictions created deep divisions in the community about when and how to reopen schools and resume operations. The role of schools in anti-racism work and promoting LGBTQ+ rights also became part of the public debate. Kai explained, “We are lucky in Vermont, but other places—not so lucky. I think Vermont teachers are aware of this, like I’m teaching this, and I couldn’t say that in Florida”. Even though educators may feel fortunate to work in a state that supports social justice ideals, one participant still conceded that the national political climate caused them to hedge somewhat and not be as direct when teaching subjects that have become hot-button issues, including issues of race, gender, sexuality, and identity.

Families had gotten a more intimate look at what and how teachers teach, which sometimes led to praise and other times to criticism. Devin, a school principal, explained, “For better or worse, there is more family awareness of what’s going on in school, and so that plays into families saying, ‘I don’t want this to be taught…” Winny spoke passionately about the debate on the school’s role in the development of students’ gender identity:

My job is not to teach…what pronoun to use. They don’t even know what a pronoun is. That is not my job. I am not going to help you decide if you are male or female. I don’t feel like I should be a part of that. No, I probably won’t. I mean, I won’t.

While Winny was the only participant who expressed this specific concern, four other educators shared experiences of how the divided political climate had impacted their teaching. Bess remembered the spring of 2020 as a period of social upheaval following the murder of George Floyd. She described this period as a time when,

From a political standpoint, [the pandemic] really divided people, and we are seeing the ripple effects. With BLM [Black Lives Matter] and all the things that were happening at the same time, how could we manage them? We were so divided… so many struggles and trauma from that.

Sam, an upper elementary teacher, agreed that some of his students had developed a stronger sense of empathy and recognition of their power in liberating others, “I think kids are kinder and more understanding and flexible [now]”.

Despite some pushback from families, nine participants shared that the community’s commitment to social justice was a strength during the pandemic. While most Vermonters are socially progressive, political divisions impact the local community. With a growing population of refugee and immigrant students from religiously conservative backgrounds, school boards, school leaders, and educators were considering how to be inclusive and non-divisive. One teacher speculated that adopting an SEL curriculum was a response to the political climate to control how teachers talk about sensitive issues. Winny speculated that,

I think the administration and teachers are afraid of being sued. It’s a sue happy community and country right now. You can say something that you don’t even realize is offensive, and somebody’s going to sue you or file a complaint… It’s more like a safeguard to say, well, we told our teachers they should be teaching this.

Overall, eight of the participants in this study expressed appreciation for working in a district that promoted social justice. Five participants identified this feature of their jobs as central to their commitment to stay in public education. Within the context of the growing demands placed on teachers, the district’s adoption of social justice standards could have been poorly received by educators. However, most participants in this study felt this was a positive development during pandemic times.