Abstract

This study examined the transition of twice-exceptional (2E) individuals from education to employment. Despite a growing focus on inclusive practices, the area of (special) education-to-work transition is still far under-researched, especially on 2E individuals. To identify challenges and success factors in this transition, a scoping review method was used. Our review revealed a paucity of targeted studies on the transition of 2E individuals to work. Four relevant studies, focusing primarily on higher education, emphasized strengths-based approaches and multi-stakeholder support to facilitate transitions. The findings underscore the need for tailored interventions and supportive environments, addressing both individual strengths and (environmental) barriers. Further research is essential in view of effective interventions to bridge the gap between education and employment for 2E individuals.

1. Introduction

The global movement toward inclusiveness caused a surge in research of people with a broad spectrum of challenges, disabilities, and adversities in education and at the workplace since the 1970s (Ashman and Elkins 2012). Despite greater moves toward inclusivity in these fields, research on people with exceptional abilities or gifts on top of their learning and/or developmental disabilities remains limited, especially in places outside of the United States. Scholars in the field of giftedness have advocated for the specialized treatment of gifted individuals for more than 90 years, reflecting a long history of recognizing the unique needs of this population; however, individuals with both high potential for achievement and creative productivity across disciplines and limitations had to wait until 2004 to be recognized in U.S. legislation (Assouline and Whiteman 2011). These individuals are known as twice-exceptionals (2E) (Reis et al. 2014), and their recognition in U.S. legislation aligns with the UNESCO (1994) Salamanca Statement Framework for Action on Special Needs Education, which emphasizes inclusion for gifted and disabled individuals (Rouse 2012). Since the recognition of the 2E, there has been increased awareness of individuals who manifest both giftedness with disability. To date, prevalence rates remain difficult to establish due to the multifaceted nature of twice-exceptionality (Rinn et al. 2020). Research estimates in the USA range from approximately 2% to 9% in schools (Barnard-Brak et al. 2015), with another study suggesting a prevalence of 2% to 5% (Nielsen 2002). In a USA study by Rogers (2011), it was found that 14% of a group of 504 students in gifted programs were twice exceptional. While research continues to contribute to the understanding of the prevalence and challenges of twice-exceptional (2E) individuals, there is a growing need to explore the transitions of these individuals both within the educational system and into the labor market.

Looking back at the recognition of the 2E concept in U.S. law and its alignment with the UNESCO Salamanca Statement, important milestones are visible. However, despite these recognitions, there remains a significant gap in the understanding when it comes to the transition of 2E individuals into the labor market. While the academic literature acknowledges the challenges faced by 2E individuals, it has largely overlooked the dynamics that characterize this stage in their lives. Recognizing the multifaceted nature of the challenges faced by 2E individuals, the literature on twice-exceptional individuals point to the need for tailored interventions and support networks as individuals navigate the complexities of professional environments. This gap in understanding how 2E individuals interact with their professional environments calls for further research. Such research is crucial to inform targeted interventions that bridge the gap between education and employment for 2E individuals, fostering their integration into the workforce. These interventions will enable 2E individuals to leverage their exceptional abilities while addressing their limitations. By expanding the research focus from educational settings to professional areas, scholars, employers and policymakers can contribute to the development of more inclusive and equitable work environments that effectively support the unique needs of the 2E population. This is in line with the research of Minnaert (2022), who concludes that the interaction between parents, teachers, and school counselors is crucial to the development of these practices. By focusing on best practices, scholars, parents, teachers, and school counselors help prevent talented individuals from experiencing frustration, reduce negative emotions and avoid dropping out of schools, the labor market, and society.

1.1. Twice-Exceptionality Presents a Multifaceted Challenge

Challenges in twice-exceptional research often arise from the unique and multifaceted nature of their conditions, which exist on a continuum due to the complex combinations of giftedness and disability (Cline and Hegeman 2001). This complexity, along with the asynchronous development typical of 2E individuals, makes it difficult for evaluators to identify them, as they may not exhibit the same characteristics as their gifted and/or non-disabled peers. Gifted individuals, who demonstrate high cognitive potential through their performance on academic tests or in creative activities, are often labeled as gifted at an early age (Renati et al. 2023). However, 2E individuals, whose development may not follow typical trajectories, are often overlooked, as they may not conform to the expected patterns of giftedness or disability (Renzulli and Gelbar 2020). For example, the developmental asynchrony experienced by 2E individuals (Silverman 2007) may lead to underachievement in education (Reis and Renzulli 2021), further complicating identification, or may lead—among expert diagnosticians—to underidentification of the gift, of the disability, or of both (Burger-Veltmeijer et al. 2015). Neihart (2002) highlights the heterogeneity of 2E individuals, who come from diverse societal backgrounds, including various nationalities, ethnicities, and socioeconomic statuses.

The unique characteristics and developmental profiles of gifted children also point to the paired complexities that come with twice-exceptionality, which is shaped by the interplay of individual and contextual factors. This complexity aligns with the Ecological Model of Bronfenbrenner (1979), which underscores the influence of both individual traits and external environments on 2E development. Vulnerability is a key issue for 2E individuals, especially for gifted students from disadvantaged backgrounds or ethnic minorities (Robbins et al. 2002; Hunter et al. 2024). These vulnerabilities are amplified during the transition to adolescence, where the increased pressures from developmental asynchrony and environmental factors may lead to higher stress levels (Coleman and Gallagher 2015). The intricate combination of these factors complicates the understanding and inclusive support of 2E individuals (Minnaert 2024), particularly during transitions between (special) educational and employment contexts.

1.2. Identifying 2E Individuals

The identification of 2E individuals presents another challenge that finds its roots primarily in the difficulties associated with establishing clear identification criteria. The academic literature often lacks a comprehensive understanding of these criteria, contributing to the broader problem of underidentification (Lovett and Lewandowski 2006; Foley-Nicpon and Teriba 2022). Further looking into the challenges of 2E research reveals the multifaceted nature of twice-exceptionality. This complexity finds its roots from the interplay of giftedness with different disabilities, making it difficult to establish universal methods of identification (Rinn et al. 2020). Among the disabilities that 2E individuals may face are ADHD, ASD, specific learning disorders, social challenges, and sensorimotor disorders (Rizza and Morrison 2007). Understanding the risk factors associated with gifted and talented children, including one or more of the aforementioned disabilities, low self-esteem, perfectionism, anxiety, struggles with stress management, depression, and other behavioral and social difficulties. This adds additional layers to the complex nature of 2E identification, and the issue is further complicated by the lack of generally accepted methods and guidelines for identification. The absence of well-established criteria contributes significantly to the persistent underidentification of 2E individuals. Moreover, the underidentification is not only due to a knowledge gap but also due to the masking effect (Beckmann and Minnaert 2018): the gift masks the disability, the disability masks the gift, or the gift and the disability mask each other. This phenomenon occurs when one aspect of an individual’s abilities or characteristics masks or hides another aspect, complicating the identification process, even among very well trained professionals (Burger-Veltmeijer et al. 2015). The absence of well-established criteria and the presence of the masking effect contribute significantly to the persistent underidentification of 2E individuals, which—as noted in the educational system of the USA—is even more the case for minoritized 2E learners (Hunter et al. 2024). This results in situations where they may be recognized for their high ability without acknowledging their impairment, identified for their impairment while their high ability is overlooked, or go completely unnoticed for both aspects because of the mutual concealment of ability and impairment (Jelly and Cormier 2023). In short, masked potentials and hidden struggles remain underexposed.

1.3. Twice-Exceptional Individuals’ Transition to Employment

With the focus on the professional domain, the transition of 2E individuals into the labor market presents yet another unique set of challenges. Despite the growing body of research on the unique challenges faced by 2E individuals, there appears to be a notable lack of studies specifically focused on the transition from 2E to work. While existing studies focus on identification and support within educational settings (e.g., Reis et al. 2014), the dynamics of transition to the workplace remain insufficiently explored for this population. Given the complex nature of 2E individuals, Renati et al. (2023) highlight the challenges associated with identifying 2E individuals. In this study, the authors state that the need for a more nuanced understanding of their experiences in the transition to work, beyond educational contexts. The authors furthermore mention that the environments must accommodate the specific needs of the 2E population. While it is widely recognized that the workplace is an important environment in which all individuals should be able to express their talents, the academic literature lacks an in-depth understanding of the ways in which 2E individuals interact with their professional employment environments. This gap needs to be filled to create focused interventions and support networks that help 2E individuals’ transition more smoothly, to make the best use of their strengths and to reduce their struggles caused by their limitations.

1.4. Objective and Research Questions

This study aims to examine the up-to-date knowledge and empirical insights on the transition of 2E individuals from (special) education to employment. Moreover, this study aims to provide a better understanding of the challenges and success factors associated with the 2E transition into employment by recognizing their talents while addressing the challenges caused by their unique characteristics. Hence, the two research questions are 1. How does the existing literature address the transition of twice-exceptional individuals from (special) education to the workplace? and 2. What specific challenges and success factors are identified in the transition phase of twice-exceptional individuals to the workplace?

2. Method

This study used a scoping review to examine the available literature on 2E individuals, specifically focusing on their transition from education to employment. This method was chosen for its ability to systematically identify, categorize, and synthesize a wide range of studies, because scoping studies encompassing a broader focus area and covering a larger volume of research, as opposed to systematic literature reviews, that focus on a narrower range of studies addressing specific research questions (Munn et al. 2018). For this study, the decision to employ a scoping review method is justified by the anticipation of encountering a diverse range of studies on 2E individuals and employment. This method is consistent with the open research goal because it allows for a comprehensive exploration of the heterogeneous literature surrounding 2E individuals, particularly with regard to their transition to employment.

2.1. PRISMA-ScR

For this study, the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews” (PRISMA-ScR), as described in detail by Tricco et al. (2018) was used. The 22-point checklist within PRISMA-ScR guided the reporting process. This approach facilitated the identification of key themes, recognition of existing knowledge gaps, and obtaining a better understanding of the current state of the literature on the transition of 2E individuals into employment. The systematic structure of PRISMA-ScR addressed the need for a solid foundation for synthesizing findings and drawing meaningful conclusions from the reviewed literature. This method allowed for the identification of evidence on the topic, exploration of knowledge gaps, and clarification of existing concepts and their characteristics (Peters et al. 2020).

2.2. Search Strategy

The search terms chosen provided comprehensive and focused review of the literature related to 2E individuals and their transition from (special) education to the workplace. The terms “twice exceptional individuals” and its variants (“2E individuals”, “gifted with disabilities” G/LD) were included. The phase of transition to work was addressed by terms such as “transition to work”, “career transition”, and “vocational experiences”, maintaining a focus on the transition from education to the workplace. The chosen terms related to learning disabilities, social challenges, and neurodiversity also acknowledged the multifaceted nature of 2E individuals and capture their diverse experiences. Furthermore, this scoping review intentionally did not have a specific time period for the literature search. This decision was made to include a broader range of relevant studies over a longer period, allowing for a wider open review of existing knowledge on the topic. The first author carried out the search. All decisions on the search term script and the time period were made in mutual agreement between the first and last author. The search term script utilized in this study can be found in Appendix A.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The aim of the inclusion criteria was to provide insight into the identification, educational experiences and transition to the workplace of twice-exceptional people. To ensure a comprehensive review, international databases PubMed, ERIC, and Scopus in English were used for literature search queries.

Three inclusion criteria were used: 1. Studies focusing on twice-exceptional (2E) individuals: Research articles, reviews, case studies, and empirical studies that specifically address the characteristics, experiences, and challenges faced by twice-exceptional individuals; 2. Educational experiences: Literature that provides insight into the identification, educational experiences, and academic performance of 2E individuals within the educational system; and 3. Transition to Workplace: Studies that explore the transition process of 2E individuals from education to work, examining factors that influence their success or challenges in professional settings.

Additionally, four exclusion criteria were applied: 1. Non-relevant topics: Studies that do not specifically address the characteristics, experiences or challenges of twice-exceptional individuals; 2. Non-English language publications: Articles and studies published in languages other than English were excluded to maintain consistency in language and facilitate thorough analysis; 3. Duplicate studies: Multiple publications reporting on the same data were excluded to avoid redundancy in the scoping review. Moreover, duplicate and triplicate studies arising from the different search engines and databases were removed; and 4. Non-peer-reviewed sources: Non-academic sources, such as opinion pieces, blog posts and non-peer-reviewed materials, were excluded to ensure the reliability and validity of the included literature and data.

The first and the last author identified the inclusion and exclusion criteria. There were no disagreements during the selection process, just some minor adjustments to (wording of the) criteria to enhance clarity and replicability.

2.4. Study Selection

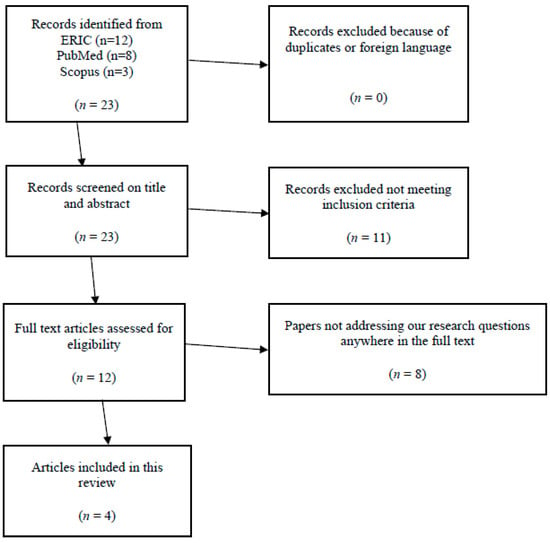

The PRISMA-ScR, as described in detail by Tricco et al. (2018), was utilized for this study. This approach incorporated the 22-point checklist, ensuring a systematic and transparent review process. The method can roughly be divided into the following seven steps: (I) We screened titles and abstracts to identify relevant studies related to 2E individuals and their transition from education to work, applying the search criteria and excluding duplicates. (II) We carefully reviewed the full text of selected studies, ensuring that they explicitly address the unique characteristics, experiences, and challenges of 2E individuals during their transition to work, along with insights into their identification, educational experiences, and work transition. (III) Studies meeting all inclusion criteria and offering insights into the transition of 2E individuals were included in the review, adhering to the PRISMA-ScR guidelines. (IV) Quality control measures were implemented to assess the reliability and relevance of the included literature, applying standard academic criteria for peer-reviewed sources. (V) The search strategy was iteratively refined to identify potential gaps or areas for improvement, ensuring comprehensive coverage of relevant literature through adjustments as needed. (VI) We used international databases such as PubMed, ERIC, and Scopus to broaden the scope of literature related to 2E individuals. (VII) The entire selection process was carefully documented to maintain transparency and reproducibility (Moher et al. 2009). The results of the literature selection process following the PRISMA-ScR guidelines are visualized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Results of literature search based on PRISMA-ScR statement.

3. Results

The transition of twice-exceptional individuals from education to employment remains a significantly under-researched area, as reflected in the limited body of literature available on the topic, most of which is concentrated in the United States. In our review, we identified only four articles that provided relevant insights into the transition of 2E individuals into the workforce, while many other studies did not meet our criteria. For example, some articles retrieved from PubMed focused on the biological basis of co-occurring conditions experienced by 2E individuals, while others from Scopus or ERIC explored topics outside the scope of this paper, such as bullying or parenting styles for caregivers of 2E children in primary school. Moreover, many studies focused on transitions within the educational system, though not explicitly on the education-to-work transition. Therefore, these records or articles were excluded during the selection process. Despite these challenges, the four studies that we did find primarily discussed other aspects of 2E individuals’ experiences, with only brief mentions of their transition into the workplace.

The study of Adreon and Durocher (2007) evaluated the transition needs of students with high-functioning ASD through interviews. Although the primary focus was on the transition to college, the study briefly discussed the importance of career centers and the lack of adequate counseling services, both of which are relevant to the transition to work for 2E individuals. The study of Kershner et al. (1995) presented a case study examining the career success of a gifted adult with a specific learning disorder. Although this study focused on career success rather than specifically on the transition to employment, it highlighted key factors relevant to the transition process, such as self-awareness of limitations, environmental management, expressive ability, and a drive for success. In the study of Madaus et al. (2023), interviews were conducted with university service providers to improve the transition to college for 2E students with ASD. While the primary focus was on the transition to college, the study addressed strengths-based opportunities in high school and noted the lack of policy mandates related to the transition to work for 2E individuals. In the study of Lin and Foley-Nicpon (2019), a literature review was performed on integrating creativity into career interventions for twice-exceptional students. Although this study did not focus directly on the transition to work, it emphasized important factors such as self-efficacy, overcoming barriers faced by underrepresented students, a person-centered approach, and the involvement of multiple stakeholders—elements that are crucial for the transition process and align with the need for tailored interventions and support networks.

Given the findings from these four studies, a targeted analysis was conducted to extract relevant information related to 2E individuals’ transition to work. The targets were the study participants, the research method used, the type of 2E, and both positive and negative factors affecting the education-to-work transition. This analysis led to the creation of Table 1, which summarizes the key findings from each article. Overall, the findings suggest that positive personal characteristics—such as self-awareness, environmental control, expressive ability, drive for success, self-efficacy, and the ability to overcome barriers—are crucial for the transition to work for 2E individuals. However, these individuals also face significant challenges due to negative environmental factors, including the need to mask or compensate for their limitations, the lack of policy mandates, and insufficient counseling services.

Table 1.

Overview of the studies focusing on factors affecting the transition to employment of twice-exceptional individuals.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study underscore significant, often overlooked gaps in the literature on the transition of 2E individuals from education to employment. Despite a growing awareness of the unique challenges this population faces, research remains sparse on the specific experiences of 2E individuals during this critical transition period. This gap is problematic, as it leaves both the strengths and the struggles of 2E individuals largely “masked” in the current research, which limits effective support for this group. The insights gathered here also offer implications for other vulnerable groups who face similarly complex barriers when transitioning to work.

A predominant theme from the literature highlights the need for a strengths-based approach in supporting 2E individuals (e.g., Madaus et al. 2023). This perspective shifts away from traditional deficit-oriented models, which tend to overlook the “masked potentials” within this group. A strengths-based approach actively recognizes and leverages the unique talents and skills of 2E individuals, creating opportunities to overcome barriers and counter the hidden struggles that may impede career success. Kershner et al. (1995), for instance, emphasized how a 2E individual with a learning disability could achieve career success by identifying and utilizing their unique strengths, illustrating how recognizing potential can guide 2E individuals toward meaningful career paths.

Recent work by Park et al. (2024) further supports the importance of both internal strengths and contextual factors. Their study on the career outcomes of adolescents with ADHD and high abilities illustrates how family background and educational aspirations influence career trajectories. This emphasis on external influences—such as family and education—alongside individual strengths reveals a more nuanced picture of 2E career development. For 2E individuals, whose struggles are often hidden within larger structural and environmental constraints, these contextual factors play a pivotal role. Such findings highlight the urgent need for strengths-based approaches that account for both the unique abilities and masked challenges of 2E individuals, aligning more effectively with the complex needs of this group. Moreover, adapting counseling methods to the nuanced profile of 2E individuals is essential to address both their strengths and their specific struggles. Foley-Nicpon (2009) notes that individualized counseling strategies are critical once a 2E individual’s strengths and concerns are identified. However, effective implementation of these tailored methods is hindered by the limited empirical evidence supporting counseling strategies for gifted populations (Wood 2010), and even more so for 2E individuals (Foley-Nicpon et al. 2011). This research gap leaves many 2E individuals without the tailored support needed to navigate the unique challenges of their transition into employment.

To effectively support 2E individuals in their transition from education to the workforce, a coordinated strategy is required—one that goes beyond traditional accommodations to actively recognize and integrate both their unique strengths and specific challenges. Educational institutions, employers, and policymakers must collaborate to establish frameworks that are adaptive to 2E needs, such as flexible hiring practices, tailored support programs, and enhanced accessibility measures (Minnaert 2024). Recognizing that 2E talents can be overshadowed by hidden struggles, interventions should emphasize individualized approaches that allow 2E individuals to express their abilities while addressing barriers unique to their profiles, like sensory or social demands in workplace settings. Studies such as those by Coleman and Gallagher (2015) underscore the importance of involving a network of supporters—including educators, career counselors, and family members—who can champion the nuanced needs of 2E individuals through tailored career guidance and work environment adjustments. Integrating career readiness programs during schooling as well as transition planning (Hunter et al. 2024), particularly those focused on self-efficacy and self-advocacy skills, is crucial for preparing 2E individuals for workplace dynamics. Additionally, family and educational supports, as identified in the findings by Park et al. (2024), significantly contribute to positive employment outcomes.

The limited amount of research explicitly addressing the specific experiences of 2E individuals during the education-to-work transition is a limitation of this scoping review, though strongly highlighting the gap in both research and evidence-based support. The most striking limitation is that the transition itself is underexposed. Another limitation is the restrictedness of the research to the educational system of the USA, strongly hampering the generalizability of findings and solutions given the world-wide differences in educational systems, school support mechanisms, diagnostic proficiencies, teacher professionalization, and national or regional policies.

The above underscores the urgency for evidence-based research aimed at creating and evaluating specific transition strategies that can reduce the barriers 2E individuals face, enabling smoother and more successful transition to sustainable careers. Currently, the education-to-work transition for 2E individuals is still a bridge too far. A step-by-step action plan is called for, in a joint effort between practice and research: transition planning is step one, transitioning from education to work is step two, and embedding the transition in the work context is step three. Only in this way can we truly do justice to the masked potentials and hidden struggles of 2E individuals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.H. and A.M.; methodology, R.H. and A.M.; validation, R.H., J.E. and A.M.; formal analysis, R.H.; investigation, R.H. and A.M.; data curation, R.H.; writing—original draft preparation, R.H.; writing—review and editing, R.H., J.E. and A.M.; visualization, R.H.; supervision, J.E. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Search Terms Deployed in Search Engines (on 27 March 2024)

(“twice-exceptional” OR “twice exceptional” OR “twice-exceptional*” “twice-exceptional individuals” OR “twice exceptional individuals” OR “2E individuals” OR “2E-individuals” “2E” OR “twice exceptional students” OR “twice-exceptional students” OR “twice exceptional adults” OR “twice-exceptional adults” OR “gifted with disabil*” OR “gifted disabil*” OR “gifted and disab*” OR “high abil*” OR “high-abil*”) AND (“learning disab*” OR “attention deficit hyperactivity disorder” OR “autism spectrum disorder” OR “ADHD” OR “ASD” OR “neurodi*” OR “cognitive div*” OR “developmental disab*”) AND (“transition” OR “employ*” OR “school-work transition” OR “transitional program*” OR “workforce” OR “career” OR “job” OR “work).

References

- Adreon, Diane, and Jennifer Stella Durocher. 2007. Evaluating the college transition needs of individuals with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Intervention in School and Clinic 42: 271–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashman, Adrian, and John Elkins. 2012. Education for Inclusion and Diversity, 4th ed. Frenchs Forest: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Assouline, Susan G., and Claire S. Whiteman. 2011. Twice-exceptionality: Implications for school psychologists in the post–IDEA 2004 era. Journal of Applied School Psychology 27: 380–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard-Brak, Lucy, Susan K. Johnsen, Alyssa Pond Hannig, and Tianlan Wei. 2015. The incidence of potentially gifted students within a special education population. Roeper Review 37: 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, Else, and Alexander Minnaert. 2018. Non-cognitive characteristics of gifted students with learning disabilities: An in-depth systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger-Veltmeijer, Agnes, Alexander Minnaert, and Els van den Bosch. 2015. Assessments of intellectually gifted students with(out) characteristic(s) of ASD: An explorative evaluation among diagnosticians in various psycho-educational organisations. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology 13: 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cline, Starr, and Kathryn Hegeman. 2001. Gifted children with disabilities. Gifted Child Today 24: 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, Mary Ruth, and Shelagh Gallagher. 2015. Meeting the needs of students with 2E: It takes a team. Gifted Child Today 38: 252–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley-Nicpon, Megan. 2009. Effective counseling approaches for talented and gifted students. Counseling and Human Development 42: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Foley-Nicpon, Megan, Allison L. Allmon, Barbara Sieck, and Rebecca D. Stinson. 2011. Empirical investigation of twice-exceptionality: Where have we been and where are we going? Gifted Child Quarterly 55: 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley-Nicpon, Megan, and Akorede Teriba. 2022. Policy considerations for twice-exceptional students. Gifted Child Today 45: 212–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, William C., Suman Rath, Keishana Barnes, LaSheba Hilliard, Caarne L. White, and Dominic McGiffert-Sandoval. 2024. “Take me to the bridge”: Transitional support for minoritized twice exceptional learners. TEACHING Exceptional Children. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelly, Kathryn C., and Damien C. Cormier. 2023. Misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis of twice-exceptional students: Examining current psychoeducational assessment practices. Practice Innovations 9: 147–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kershner, John, Terry Kirkpatrick, and Dana McLaren. 1995. The career success of an adult with a learning disability: A psychosocial study of amnesic-semantic aphasia. Journal of Learning Disabilities 28: 121–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Ching-Lan Rosaline, and Megan Foley-Nicpon. 2019. Integrating creativity into career interventions for twice-exceptional students in the United States: A review of recent literature. Gifted and Talented International 34: 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovett, Benjamin J., and Lawrence J. Lewandowski. 2006. Gifted students with learning disabilities: Who are they? Journal of Learning Disabilities 39: 515–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madaus, Joseph, Alexandra Cascio, Julie Delgado, Nicholas Gelbar, Sally Reis, and Emily Tarconish. 2023. Improving the transition to college for Twice-Exceptional students with ASD: Perspectives from college service providers. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals 46: 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnaert, Alexander. 2022. Inclusive support to safeguard the strengths of Twice-Exceptional students. Madridge Journal of Behavioral and Social Sciences 5: 86–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnaert, Alexander. 2024. Twice-exceptional students: Balancing between gift and challenge. In I Linguaggi Della Pedagogia Speciale. La Prospettiva dei Valori e dei Contesti di Vita. Edited by Stefania Pinnelli, Andrea Fiorucci and Catia Giaconi. Lecce: Pensa MultiMedia, pp. 17–21. Available online: https://www.pensamultimedia.it/libro/9791255681526 (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Moher, David, Alessandro Liberati, Jennifer Tetzlaff, and Douglas G. Altman. 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine 6: e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Zachary, Micah D. Peters, Cindy Stern, Catalin Tufanaru, Alexa McArthur, and Edoardo Aromataris. 2018. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology 18: 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neihart, Maureen Frances. 2002. Risk and resilience in gifted children: A conceptual framework. In The Social and Emotional Development of Gifted Children: What Do We Know. Edited by Maureen Neihart. Waco: Prufrock Press, pp. 113–22. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, M. Elizabeth. 2002. Gifted students with learning disabilities: Recommendations for identification and programming. Exceptionality 10: 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Soeun, Megan Foley-Nicpon, and Duhita Mahatmya. 2024. Young adult career outcomes for adolescents with ADHD, high ability, or Twice-Exceptionality. Journal for the Education of the Gifted 47: 237–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, Micah, Christina M. Godfrey, Patricia McInerney, Zachary Munn, Andrea Tricco, and Hanna Khalil. 2020. Scoping reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Edited by Edoardo Aromataris and Zachary Munn. Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual, JBI. (accessed on 20 December 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Reis, Sally M., and Sara J. Renzulli. 2021. Parenting for strengths: Embracing the challenges of raising children identified as twice exceptional. Gifted Education International 37: 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, Sally M., Susan M. Baum, and Edith Burke. 2014. An operational definition of twice-exceptional learners. Gifted Child Quarterly 58: 217–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renati, Roberta, Natale Salvatore Bonfiglio, Martina Dilda, Maria Lidia Mascia, and Maria Pietronilla Penna. 2023. Gifted children through the eyes of their parents: Talents, social-emotional challenges, and educational strategies from preschool through middle school. Children 10: 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzulli, Sara J., and Nicholas Gelbar. 2020. Leadership roles for school counselors in identifying and supporting Twice-Exceptional (2E) students. Professional School Counseling 23: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinn, Anne, Rachel U. Mun, and Jaret Hodges. 2020. 2018–2019 State of the States in Gifted Education. Washington, DC: National Association of Gifted Children and the Council of State Directors of Programs for the Gifted. Available online: https://cdn.ymaws.com/nagc.org/resource/resmgr/state_of_the_states_report/2018-2019_state_of_the_state.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Rizza, Marry G., and William F. Morrison. 2007. Identifying twice exceptional children: A toolkit for success. Teaching Exceptional Children Plus 3: 3. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, Rockey, Stuart Tonemah, and Sharla Robbins. 2002. Project Eagle: Techniques for multi-family psycho-educational group therapy with gifted American Indian adolescents and their parents. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research 10: 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, Karen B. 2011. Thinking smart about twice exceptional learners: Steps for finding them and strategies for catering to them appropriately. In Dual Exceptionality. Edited by Catherine Wormald and Wilma Viall. Casuarina: AAEGT, pp. 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Rouse, Martyn. 2012. Foreword. In Future Directions for Inclusive Teacher Education: An International Perspective. Edited by Chris Forlin. Milton Park: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, Linda K. 2007. What We Have Learned About Gifted Children: 1979–2007. Westminster: Gifted Development Center. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, Andrea C., Erin Lillie, Wasifa Zarin, Kelly K. O’Brien, Heather Colquhoun, Danielle Levac, David Moher, Micah D. Peters, Tanya Horsley, Laura Weeks, and et al. 2018. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine 169: 467–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. 1994. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. Paris: UNESCO. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000098427 (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Wood, Susannah. 2010. Best practices in counseling the gifted in schools: What’s really happening? Gifted Child Quarterly 54: 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).