Staying or Moving: Racial Differences in Single Mothers’ Residential Stability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Theory

2.1. Black Single Mothers and Urban Poverty: A Brief History

2.2. Theories of Racial Residential Stratification

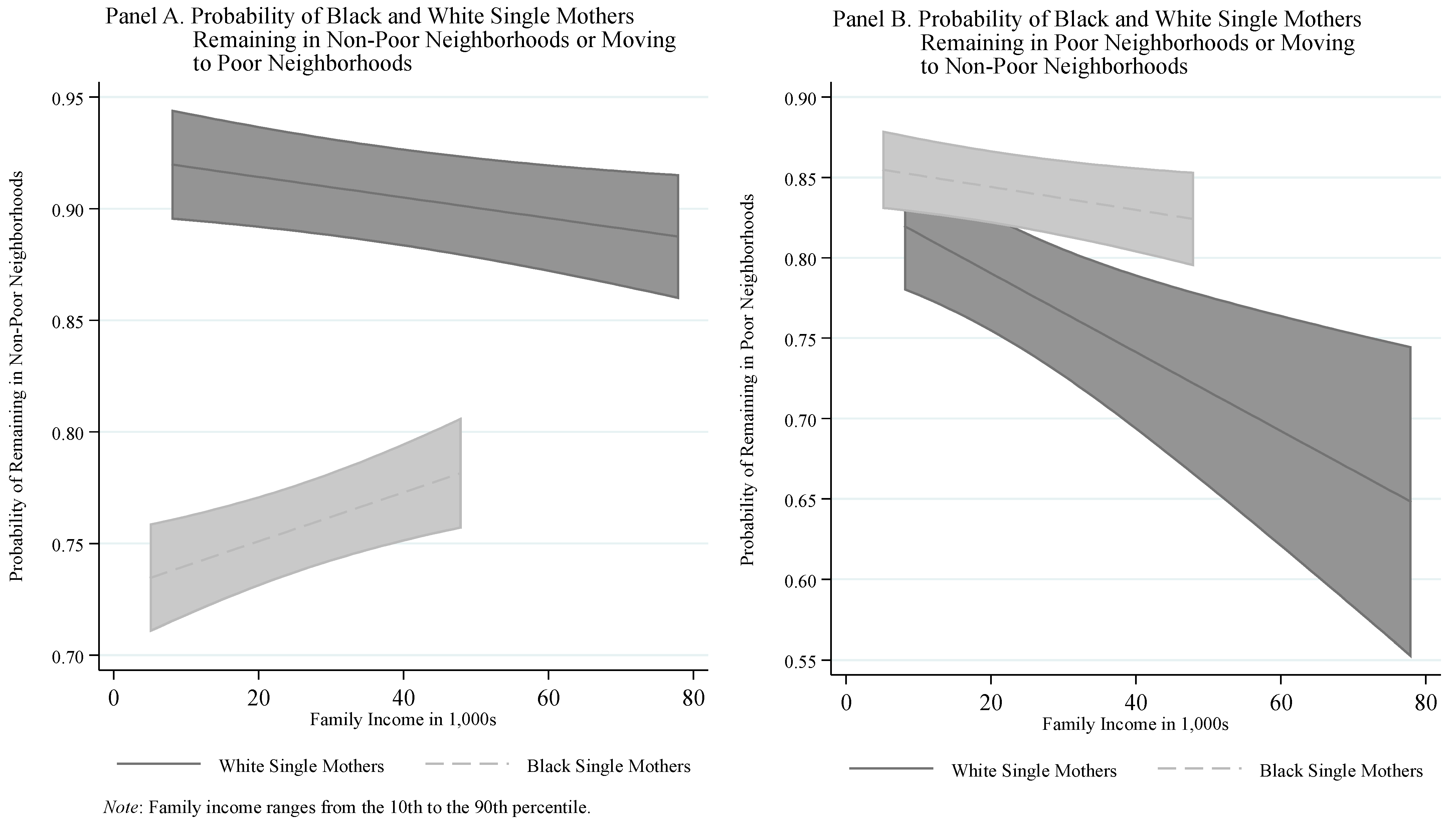

- How do Black single mothers compare to White single mothers in their probability of staying in non-poor neighborhoods rather than moving to poor neighborhoods?

- How do Black single mothers compare to White single mothers in their probability of staying in poor neighborhoods rather than moving to non-poor neighborhoods?

- Does controlling for racial differences in socioeconomic, demographic, and contextual characteristics account for racial differences in who stays in non-poor or poor neighborhoods?

- 4.

- Does the probability of remaining in non-poor or poor neighborhoods for Black and White single mothers vary by economic resources?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dependent Variables

3.2. Independent Variables

3.3. Analytic Strategy

4. Results

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ackert, Elizabeth, Amy Spring, Kyle Crowder, and Scott J. South. 2019. Kin Location and Racial Disparities in Exiting and Entering Poor Neighborhoods. Social Science Research 84: 102346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, Richard D., and John R. Logan. 1991. Variations on Two Themes: Racial and Ethnic Patterns in the Attainment of Suburban Residence. Demography 28: 431–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alba, Richard D., and John R. Logan. 1993. Locational Returns to Human Capital: Minority Access to Suburban Community Resources. Demography 28: 243–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Elijah. 2015. The White Space. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 1: 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. 2019. Feeling Race: Theorizing the Racial Economy of Emotions. American Sociological Review 84: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broussard, C. Anne. 2010. Research Regarding Low-Income Single Mothers’ Mental and Physical Health: A Decade in Review. Journal of Poverty 14: 443–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Lauren, Urbano L. França, and Michael L. McManus. 2023. Neighborhood Poverty and Distance to Pediatric Hospital Care. Academic Pediatrics 23: 1276–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, Camille Zubrinksy. 2006. Won’t You be My Neighbor: Race, Class, and Residence in Los Angeles. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, Camille Zubrinsky. 2003. The Dynamics of Racial Residential Segregation. Annual Review of Sociology 29: 167–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, Raj, Nathaniel Hendren, and Lawrence F. Katz. 2016. The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children: New Evidence from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment. American Economic Review 106: 855–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, Peter, and Christopher Timmins. 2022. Sorting or Steering: The Effects of Housing Discrimination on Neighborhood Choice. Journal of Political Economy 130: 2110–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulton, Claudia, Brett Theodos, and Margery A Turner. 2012. Residential Mobility and Neighborhood Change: Real Neighborhoods Under the Microscope. Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research 14: 55–89. [Google Scholar]

- Crowder, Kyle, and Liam Downey. 2010. Interneighborhood Migration, Race, and Environmental Hazards: Modeling Microlevel Processes of Environmental Inequality. American Journal of Sociology 115: 1110–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damaske, Sarah, Jenifer L. Bratter, and Adrianne Frech. 2017. Single Mother Families and Employment, Race, and Poverty in Changing Economic Times. Social Science Research 62: 120–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmond, Matthew. 2012. Eviction and the Reproduction of Urban Poverty. American Journal of Sociology 118: 88–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmond, Matthew. 2016. Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City. New York: Crown Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Do, D. Phuong, Lu Wang, and Michael R. Elliott. 2013. Investigating the Relationship between Neighborhood Poverty and Mortality Risk: A Marginal Structural Modeling Approach. Social Science and Medicine 91: 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, Rachel. E. 2007. Expanding Homes and Increasing Inequalities: U.S. Housing Development and the Residential Segregation of the Affluent. Social Problems 54: 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emirbayer, Mustafa, and Matthew Desmond. 2015. The Racial Order. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Faber, Jacob William, and Jocelyn Pak Drummond. 2024. Still Victimized in a Thousand Ways: Segregation as a Tool for Exploitation in the Twenty-First Century. Annual Review of Sociology 50: 501–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firebaugh, Glenn, and Chad R. Farrell. 2016. Still Large, but Narrowing: The Sizable Decline in Racial Neighborhood Inequality in Metropolitan America, 1980–2010. Demography 53: 139–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, E. Franklin. 1968. On Race Relations. Edited by G. Franklin Edwards. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Galster, George, and Patrick Sharkey. 2017. Spatial Foundations of Inequality: A Conceptual Model and Empirical Overview. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 3: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GeoLytics. 2013. Neighborhood Change Database [Database]. East Brunswick: GeoLytics, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, Cynthia, Marnie Purciel-Hill, Nirupa R. Ghai, Leslie Kaufman, Regina Graham, and Gretchen Van Wye. 2011. Measuring Food Deserts in New York City’s Low-Income Neighborhoods. Health and Place 17: 696–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, David J. 2010. Living the Drama: Community, Conflict, and Culture Among Inner-City Boys. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hepburn, Peter, Renee Louis, and Matthew Desmond. 2020. Racial and Gender Disparities among Evicted Americans. Sociological Science 7: 649–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Ying, Scott J. South, Amy Spring, and Kyle Crowder. 2021. Life-Course Exposure to Neighborhood Poverty and Migration Between Poor and Non-Poor Neighborhoods. Population Research and Policy Review 40: 401–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, Marcus Anthony, and Zandria F. Robinson. 2016. The Sociology of Urban Black America. Annual Review of Sociology 42: 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jargowsky, Paul A. 1996. Take the Money and Run: Economic Segregation in U.S. Metropolitan Areas. American Sociological Review 61: 984–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jargowsky, Paul A. 1997. Poverty and Place: Ghettos, Barrios, and the American City. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Yeonwoo, Sharon Lee, Hyejin Jung, Jose Jaime, and Catherine Cubbin. 2019. Is Neighborhood Poverty Harmful to Every Child? Neighborhood Poverty, Family Poverty, and Behavioral Problems among Young Children. Journal of Community Psychology 47: 594–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kravitz-Wirtz, Nicole, Samantha Teixeira, Anjum Hajat, Bongki Woo, Kyle Crowder, and David Takeuchi. 2018. Early-Life Air Pollution Exposure, Neighborhood Poverty, and Childhood Asthma in the United States, 1990–2014. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15: 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krivo, Lauren J, Ruth D Peterson, and Danielle C Kuhl. 2009. Segregation, Racial Structure, and Neighborhood Violent Crime. American Journal of Sociology 114: 1765–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladner, Joyce A. 1971. Tomorrow’s Tomorrow: The Black Woman. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, vol. 839. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Kwan Ok, Richard Smith, and George Galster. 2017. Neighborhood Trajectories of Low-Income U.S. Households: An Application of Sequence Analysis. Journal of Urban Affairs 39: 335–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, John R., and Harvey L. Molotch. 1987. Urban Fortunes: The Political Economy of Place. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, Douglas S., and Brendan P. Mullan. 1984. Processes of Hispanic and Black Spatial Assimilation. American Journal of Sociology 89: 836–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, Douglas S., and Garvey Lundy. 2001. Use of Black English and Racial Discrimination in Urban Housing Markets: New Methods and Findings. Urban Affairs Review 36: 452–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, Douglas S., and Nancy A. Denton. 1993. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, Katrina Bell, and Bedelia Nicola Richards. 2008. Downward Residential Mobility in Structural-Cultural Context: The Case of Disadvantaged Black Mothers. Black Women, Gender + Families 2: 25–53. [Google Scholar]

- Mood, Carina. 2010. Logistic Regression: Why We Cannot Do What We Think We Can Do, and What We Can Do About It. European Sociological Review 26: 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, Taryn W., and Katie M. Vinopal. 2018. Neighborhood Poverty and Children’s Academic Skills and Behavior in Early Elementary School. Journal of Marriage and Family 80: 182–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, Daniel P. 1965. The Negro Family: The Case for National Action; Washington, DC: Office of Policy Planning and Research, United States Department of Labor.

- Pais, Jeremy F., Scott J. South, and Kyle Crowder. 2009. White Flight Revisited: A Multiethnic Perspective on Neighborhood Out-Migration. Population Research and Policy Review 28: 321–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais, Jeremy, Scott J South, and Kyle Crowder. 2012. Metropolitan Heterogeneity and Minority Neighborhood Attainment: Spatial Assimilation or Place Stratification? Social Problems 59: 258–81. [Google Scholar]

- Panel Study of Income Dynamics, Restricted Use Data. 2024. Ann Arbor: Produced and Distributed by the Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan.

- Pettit, Becky, and Stephanie Ewert. 2009. Employment Gains and Wage Declines: The Erosion of Black Women’s Relative Wages Since 1980. Demography 46: 469–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radford-Hill, Sheila. 2000. Further to Fly: Black Women and the Politics of Empowerment. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rérat, Patrick. 2020. Residential Mobility. In Handbook of Urban Mobilities, 1st ed. Edited by Ole B. Jensen, Claus Lassen, Vincent Kaufmann, Malene Freudendal-Pedersen and Ida Sofie Gøtzsche Lange. Milton Park: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Roscigno, Vincent J, Diana L Karafin, and Griff Tester. 2009. The Complexities and Processes of Racial Housing Discrimination. Social Problems 56: 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, Peter. 1955. Why Families Move. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, Robert J. 2012. Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, Robert J., Jeffrey D. Morenoff, and Thomas Gannon-Rowley. 2002. Assessing ‘Neighborhood Effects’: Social Processes and New Directions in Research. Annual Review of Sociology 28: 443–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, Patrick. 2008. The Intergenerational Transmission of Context. American Journal of Sociology 113: 931–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, Patrick, and Felix Elwert. 2011. The Legacy of Disadvantage: Multigenerational Neighborhood Effects on Cognitive Ability. American Journal of Sociology 116: 1934–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, Patrick, and Jacob W. Faber. 2014. Where, When, Why, and For Whom Do Residential Contexts Matter? Moving Away from the Dichotomous Understanding of Neighborhood Effects. Annual Review of Sociology 40: 559–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, Patrick, and Robert J. Sampson. 2010. Destination Effects: Residential Mobility and Trajectories of Adolescent Violence in a Stratified Metropolis. Criminology 48: 639–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- South, Scott J., and Kyle D. Crowder. 1997. Escaping Distressed Neighborhoods: Individual, Community, and Metropolitan Influences. American Journal of Sociology 102: 1040–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South, Scott J., and Kyle D. Crowder. 1998. Avenues and Barriers to Residential Mobility among Single Mothers. Source: Journal of Marriage and Family 60: 866–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South, Scott J., Kyle Crowder, and Erick Chavez. 2005. Exiting and Entering High Poverty Neighborhoods: Latinos, Blacks and Anglos Compared. Social Forces 84: 873–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South, Scott J., Ying Huang, Amy Spring, and Kyle Crowder. 2016. Neighborhood Attainment over the Adult Life Course. American Sociological Review 81: 1276–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spring, Amy, Elizabeth Ackert, Kyle Crowder, and Scott J South. 2017. Influence of Proximity to Kin on Residential Mobility and Destination Choice: Examining Local Movers in Metropolitan Areas. Demography 54: 1277–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, Carol B. 1974. All Our Kin: Strategies for Survival in a Black Community, 1st ed. Manhattan: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Tolnay, Stewart E. 2001. The Great Migration Gets Underway: A Comparison of Black Southern Migrants and Nonmigrants in the North, 1920. Social Science Quarterly 82: 235–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, Margery Austin, Rob Santos, Diane K Levy, Doug Wissoker, Claudia Aranda, and Rob Pitingolo. 2013. Housing Discrimination Against Racial and Ethnic Minorities 2012; Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

- US Census Bureau. 2023. Table CH-3. Living Arrangements of Black Children Under 18 Years Old: 1960 to Present. Available online: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/families/children.html (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- VonLockette, Nick Dickerson. 2010. The Impact of Metropolitan Residential Segregation on the Employment Chances of Blacks and Whites in the United States. City & Community 9: 256–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Kyungsoon, and Dan Immergluck. 2019. Housing Vacancy and Urban Growth: Explaining Changes in Long-Term Vacancy after the US Foreclosure Crisis. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 34: 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Michael J. 1987. American Neighborhoods and Residential Differentiation. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, William Julius. 1987. The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wodtke, Geoffrey T., David J. Harding, and Felix Elwert. 2011. Neighborhood Effects in Temporal Perspective: The Impact of Long-Term Exposure to Concentrated Disadvantage on High School Graduation. American Sociological Review 76: 713–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolch, Jennifer, John Wilson, and Jed Fehrenbach. 2005. Parks and Park Funding in Los Angeles: An Equity-Mapping Analysis. Urban Geography 26: 4–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| In a Non-Poor Tract at Time t | In a Poor Tract at Time t | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black Single Mothers | White Single Mothers | Black Single Mothers | White Single Mothers | ||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Dependent Variables | |||||||||

| Percent remaining in a Non-Poor, Time t to t + 1 | 81.44 | 38.87 | 94.25 | 23.26 | |||||

| N | 3139 | 2693 | |||||||

| Percent remaining in a Poor Tract, Time t to t + 1 | 88.91 | 31.39 | 83.05 | 37.53 | |||||

| N | 6877 | 755 | |||||||

| Socioeconomic Characteristics | |||||||||

| Family Income (in $1000s) | 25.08 | 18.43 | 35.79 | 31.95 | 18.09 | 13.91 | 18.66 | 15.16 | |

| Education (in Years) | 12.08 | 2.43 | 12.43 | 2.95 | 11.36 | 2.10 | 10.49 | 3.05 | |

| Employed (1 = Yes) | 0.68 | 0.47 | 0.73 | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.48 | 0.50 | |

| Homeowner (1 = Yes) | 0.27 | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0.20 | 0.40 | |

| Demographic Characteristics | |||||||||

| Age | 34.95 | 8.79 | 37.23 | 8.80 | 33.96 | 8.79 | 35.70 | 9.43 | |

| Average Age of Children | 9.68 | 4.59 | 10.11 | 4.62 | 9.38 | 4.62 | 9.62 | 4.73 | |

| Number of Children | 2.15 | 1.34 | 1.82 | 1.05 | 2.34 | 1.39 | 2.11 | 1.30 | |

| Persons Per Room | 0.79 | 0.48 | 0.67 | 0.45 | 0.87 | 0.55 | 0.86 | 0.49 | |

| Same House 3+ Years (1 = Yes) | 0.38 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.50 | |

| Contextual Characteristics | |||||||||

| Percent Homeowners, Tract | 57.35 | 18.97 | 62.99 | 18.52 | 35.45 | 18.89 | 36.47 | 19.00 | |

| Dissimilarity, Metro | 0.65 | 0.12 | 0.65 | 0.14 | 0.70 | 0.12 | 0.65 | 0.13 | |

| Percent Black Individuals, Metro | 21.55 | 9.75 | 11.87 | 9.12 | 21.74 | 9.57 | 11.23 | 7.36 | |

| Percent Poverty, Metro | 11.84 | 3.32 | 11.49 | 2.86 | 12.36 | 3.33 | 13.42 | 4.74 | |

| Population Size (ln), Metro | 14.40 | 1.10 | 14.23 | 1.39 | 14.57 | 1.08 | 14.48 | 1.45 | |

| Percent Units Built 0–10 Yrs. Ago, Metro | 22.68 | 8.66 | 20.33 | 9.16 | 22.14 | 8.99 | 19.45 | 10.06 | |

| Percent Housing Units Vacant, Metro | 7.53 | 2.57 | 7.24 | 3.96 | 7.17 | 2.40 | 7.74 | 3.82 | |

| Year at End of Observation | 1990.69 | 12.60 | 1988.96 | 11.68 | 1987.44 | 11.65 | 1990.45 | 11.55 | |

| Length of Observation Period | 1.32 | 0.47 | 1.23 | 0.42 | 1.21 | 0.41 | 1.23 | 0.42 | |

| N of Single Parent Observations | 3854 | 2857 | 7734 | 909 | |||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | ||||||||

| Single Parents | |||||||||||||||

| Black Single Mothers | −0.1971 | *** | (0.0151) | −0.1527 | *** | (0.0144) | −0.1427 | *** | (0.0140) | −0.1512 | *** | (0.0149) | |||

| Socioeconomic Characteristics | |||||||||||||||

| Family Income (in $1000s) | 0.0002 | (0.0002) | −0.0000 | (0.0002) | −0.0001 | (0.0002) | |||||||||

| Education (in Years) | 0.0120 | *** | (0.0025) | 0.0126 | *** | (0.0024) | 0.0123 | *** | (0.0024) | ||||||

| Employed (1 = Yes) | 0.0436 | *** | (0.0100) | 0.0398 | *** | (0.0100) | 0.0400 | *** | (0.0100) | ||||||

| Homeowner (1 = Yes) | 0.1424 | *** | (0.0118) | 0.1120 | *** | (0.0122) | 0.1126 | *** | (0.0125) | ||||||

| Demographic Characteristics | |||||||||||||||

| Age | 0.0053 | *** | (0.0010) | 0.0054 | *** | (0.0010) | |||||||||

| Average Age of Children | 0.0045 | (0.0043) | 0.0001 | (0.0016) | |||||||||||

| Number of Children | 0.0003 | (0.0016) | 0.0048 | (0.0043) | |||||||||||

| Persons Per Room | −0.0365 | *** | (0.0097) | −0.0349 | *** | (0.0097) | |||||||||

| Same House 3+ Years (1 = Yes) | −0.0016 | (0.0089) | −0.0020 | (0.0089) | |||||||||||

| Contextual Characteristics | |||||||||||||||

| Percent Homeowners, Tract | −0.0001 | (0.0003) | |||||||||||||

| Dissimilarity, Metro | −0.0185 | * | (0.0079) | ||||||||||||

| Percent Black Individuals, Metro | 0.0025 | ** | (0.0008) | ||||||||||||

| Percent Poverty, Metro | −0.0097 | *** | (0.0025) | ||||||||||||

| Population Size (ln), Metro | 0.0045 | (0.0071) | |||||||||||||

| Percent Units Built 0–10 Yrs. Ago, Metro | −0.0019 | (0.0011) | |||||||||||||

| Percent Housing Units Vacant, Metro | 0.0020 | (0.0024) | |||||||||||||

| Year | −0.0007 | (0.0007) | −0.0018 | ** | (0.0007) | −0.0029 | *** | (0.0007) | −0.0044 | *** | (0.0011) | ||||

| Length of observation | −0.0203 | (0.0165) | −0.0384 | * | (0.0163) | −0.0400 | (0.0163) | −0.0402 | * | (0.0164) | |||||

| Intercept | 2.3784 | (1.3469) | 4.3249 | ** | (1.3332) | 6.2831 | *** | (1.3537) | 9.4509 | *** | (2.0933) | ||||

| Variance Components | |||||||||||||||

| Between MSAs | −2.7792 | *** | (0.1851) | −2.8554 | *** | (0.1789) | −2.9566 | *** | (0.1938) | −3.3725 | *** | (0.3359) | |||

| Between Individuals | −1.3765 | *** | (0.0292) | −1.4835 | *** | (0.0325) | −1.5301 | *** | (0.0346) | −1.5297 | *** | (0.0345) | |||

| Residual | −1.3559 | *** | (0.0113) | −1.3505 | *** | (0.0115) | −1.3471 | *** | (0.0116) | −1.3467 | *** | (0.0116) | |||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | ||||||||

| Single Parents | |||||||||||||||

| Black Single Mothers | 0.0287 | (0.0174) | 0.0452 | ** | (0.0144) | 0.0487 | ** | (0.0164) | 0.0519 | ** | (0.0171) | ||||

| Socioeconomic Characteristics | |||||||||||||||

| Family Income (in $1000s) | −0.0004 | (0.0003) | −0.0010 | ** | (0.0003) | −0.0009 | ** | (0.0003) | |||||||

| Education (in Years) | −0.0099 | *** | (0.0022) | −0.0062 | ** | (0.0022) | −0.0051 | * | (0.0022) | ||||||

| Employed (1 = Yes) | −0.0091 | (0.0084) | −0.0115 | (0.0084) | −0.0123 | (0.0084) | |||||||||

| Homeowner (1 = Yes) | 0.0834 | *** | (0.0121) | 0.0633 | *** | (0.0122) | 0.0643 | *** | (0.0123) | ||||||

| Demographic Characteristics | |||||||||||||||

| Age | 0.0035 | *** | (0.0008) | 0.0035 | *** | (0.0008) | |||||||||

| Average Age of Children | −0.0002 | (0.0014) | −0.0002 | (0.0014) | |||||||||||

| Number of Children | 0.0004 | (0.0032) | −0.0001 | (0.0032) | |||||||||||

| Persons Per Room | −0.0024 | (0.0071) | −0.0032 | (0.0071) | |||||||||||

| Same House 3+ Years (1 = Yes) | 0.0222 | ** | (0.0078) | 0.0219 | ** | (0.0078) | |||||||||

| Contextual Characteristics | |||||||||||||||

| Percent Homeowners, Tract | 0.0002 | (0.0003) | |||||||||||||

| Dissimilarity, Metro | 0.0203 | * | (0.0090) | ||||||||||||

| Percent Black Individuals, Metro | 0.0001 | (0.0009) | |||||||||||||

| Percent Poverty, Metro | 0.0116 | *** | (0.0021) | ||||||||||||

| Population Size (ln), Metro | 0.0195 | * | (0.0089) | ||||||||||||

| Percent Units Built 0–10 Yrs. Ago, Metro | −0.0006 | (0.0012) | |||||||||||||

| Percent Housing Units Vacant, Metro | −0.0026 | (0.0029) | |||||||||||||

| Year | −0.0013 | * | (0.0006) | −0.0007 | (0.0006) | −0.0012 | * | (0.0006) | −0.0011 | (0.0011) | |||||

| Length of observation | −0.0722 | *** | (0.0147) | −0.0751 | *** | (0.0148) | −0.0759 | *** | (0.0147) | −0.0750 | *** | (0.0149) | |||

| Intercept | 3.3637 | ** | (1.1084) | 2.3316 | * | (1.1300) | 3.2328 | ** | (1.1336) | 2.3901 | (2.0933) | ||||

| Variance Components | |||||||||||||||

| Between MSAs | −2.3933 | *** | (0.1554) | −2.4142 | *** | (0.1526) | −2.5332 | *** | (0.1620) | −2.7658 | *** | (0.2234) | |||

| Between Individuals | −1.7818 | *** | (0.0460) | −1.8398 | *** | (0.0496) | −1.9482 | *** | (0.0604) | −1.9413 | *** | (0.0600) | |||

| Residual | −1.2684 | *** | (0.0097) | −1.2655 | *** | (0.0098) | −1.2558 | *** | (0.0102) | −1.2577 | *** | (0.0101) | |||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remain in Non-Poor vs. Move to Poor | Remain in Poor vs. Move to Non-Poor | ||||||

| Black Single Mothers | −0.1944 | *** | (0.0184) | 0.0190 | (0.0231) | ||

| Family Income (in $1000s) | −0.0005 | * | (0.0002) | −0.0025 | ** | (0.0008) | |

| Black Single Mothers X Family Income (in $1000s) | 0.0016 | *** | (0.0004) | 0.0017 | * | (0.0008) | |

| Socioeconomic, Demographic, and Contextual Controls | Y | Y | |||||

| Year | −0.0043 | *** | (0.0010) | −0.0011 | (0.0011) | ||

| Length of observation | −0.0425 | ** | (0.0164) | −0.0748 | *** | (0.0149) | |

| Intercept | 9.3875 | *** | (2.0778) | 2.5644 | (2.1590) | ||

| Variance Components | |||||||

| Between MSAs | −3.4133 | *** | (0.3502) | −2.7734 | *** | (0.2245) | |

| Between Individuals | −1.5435 | *** | (0.0352) | −1.9403 | *** | (0.0600) | |

| Residual | −1.3448 | *** | (0.0117) | −1.2580 | *** | (0.0102) | |

| N | 6711 | 8643 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gabriel, R.; Polhill, P.; Waite, A. Staying or Moving: Racial Differences in Single Mothers’ Residential Stability. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14030149

Gabriel R, Polhill P, Waite A. Staying or Moving: Racial Differences in Single Mothers’ Residential Stability. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(3):149. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14030149

Chicago/Turabian StyleGabriel, Ryan, Peter Polhill, and Adrienne Waite. 2025. "Staying or Moving: Racial Differences in Single Mothers’ Residential Stability" Social Sciences 14, no. 3: 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14030149

APA StyleGabriel, R., Polhill, P., & Waite, A. (2025). Staying or Moving: Racial Differences in Single Mothers’ Residential Stability. Social Sciences, 14(3), 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14030149