Abstract

Background: Ableism obstructs employment equity for disabled individuals. However, research lacks a comprehensive understanding of how ableism multidimensionally manifests across job types, disability types, stages of employment, and intersecting identities. Objectives: This scoping review examines how ableism affects disabled workers and jobseekers, as well as its impacts on employment outcomes, variations across disabilities and identities, and the best practices for addressing these. Eligibility Criteria: The included articles were 109 peer-reviewed empirical studies conducted in the US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the UK, Ireland, Denmark, Sweden, Iceland, Norway, and Finland between 2018 and 2023. Sources of Evidence: Using terms related to disability, ableism, and employment, the databases searched included Sociology Collection, CINAHL, PsycInfo, Web of Science, SCOPUS, Education Source, Academic Search Complete, and ERIC. Charting Methods: Data were extracted in tabular form and analyzed through thematic narrative synthesis to identify study characteristics, ableist barriers within employment, intersectional factors, and best practices. Results: Ableism negatively impacts employment outcomes through barriers within the work environment, challenges in disclosing disabilities, insufficient accommodations, and workplace discrimination. Intersectional factors intensify inequities, particularly for BIPOC, women, and those with invisible disabilities. Conclusions: Systemic, intersectional strategies are needed to address ableism, improve policies, and foster inclusive workplace practices.

1. Introduction

Worldwide, people with disabilities have long experienced exclusion, marginalization and discrimination across sectors (Harpur et al. 2019; Lindsay et al. 2019a; Ontario Human Rights Commission 2016; Schur et al. 2020). This pervasive inequity, often referred to as ableism, can be understood as a hierarchical system of discrimination and exclusion that privileges those without disabilities while systematically disadvantaging and devaluing people with disabilities, often reinforcing layers of oppression based on different identity markers (Campbell 2009). Globally, ableism has been widely documented across various settings, including the workplace; indeed, despite the rise in protective legislation surrounding diversity in the workplace, people with disabilities still do not experience equitable access to work opportunities compared to their counterparts without a disability (Bonaccio et al. 2020). Studies show that disability-based discrimination persists in hiring, retention, and promotion practices, reflecting the systemic undervaluation of disabled workers, as many employers continue to enact prejudiced and discriminatory views regarding the work-related abilities of people with disabilities (Bonaccio et al. 2020; Harpur et al. 2019; Lindsay et al. 2019a; Schur et al. 2020). This ableism disrupts the employment cycle for disabled jobseekers and employees, contributing to widespread exclusion and correlating with inequitable occupational and psychosocial outcomes, such as higher unemployment rates, lower income levels, and reduced access to adequate and affordable housing when compared to individuals without disabilities (Østerud 2022a; Statistics Canada 2017; Santuzzi et al. 2022).

In this review, we follow the United Nations’ description of disability as “long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others” (United Nations n.d.). Relatedly, it is imperative to note that disabled employees and jobseekers represent a multifaceted and heterogenous population, defying a unidimensional understanding of “disability”. In addition to the type of disability, i.e., physical disabilities (e.g., cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis), intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDDs) (e.g., Down’s syndrome, Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)), neurological and learning disorders (e.g., Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), dyslexia), chronic illnesses (e.g., lupus, Parkinson’s disease), and mental illnesses (e.g., schizophrenia, Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder (OCD)), a variety of social determinants such as geographic location, race and ethnicity, culture, socioeconomic status, gender and sexuality, interpersonal relationships, and support needs, among others, differentiate the experiences of working-age disability populations (Hedley et al. 2021; Hoque and Bacon 2022; Lindsay et al. 2019a; Østerud 2022a; Sprong et al. 2020). For example, individuals with invisible disabilities, such as mental health conditions or chronic illnesses, often face heightened skepticism about their capabilities, resulting in fewer accommodations and increased stigma compared to those with visible physical disabilities (Bonaccio et al. 2020). In defining workplace ableism, it is, therefore, essential to underscore its hierarchical nature and multiple social dimensions, illustrating how workplace interactions can reinforce discriminatory practices and produce varying levels of oppression across different subpopulations. Similarly, it is crucial to identify and analyze specific components of ableism in employment, including barriers across disability types and employment stages, forms of ableist and intersectional discrimination, and employer practices to address these challenges.

Despite the growing recognition of workplace ableism, gaps remain in research to comprehensively address the multifaceted impacts ableism has on disabled workers and jobseekers. Existing research often fails to fully examine the specifics of how ableism manifests across job types, as well as how it evolves across stages of the employment cycle (i.e., recruitment, hiring, integration, and performance management). Existing studies also tend to focus narrowly on specific disability groups or single dimensions of identity, neglecting the intersectional realities of how factors like disability type, race, gender, and socioeconomic status amplify discrimination (Hedley et al. 2021; Lindsay et al. 2019a; Østerud 2022b). These limitations highlight the need for a broader, more integrated understanding of how ableism operates across diverse contexts and populations. A scoping review was deemed appropriate for addressing these gaps, as it allows for a comprehensive exploration of diverse evidence and captures the complexity of ableism’s impacts across employment stages, disability types, and intersecting identities (Arksey and O’Malley 2005; Levac et al. 2010). This methodology is particularly suited to mapping the breadth of existing research, identifying patterns and gaps, and highlighting underexplored areas in ways that more narrowly focused approaches do not (Munn et al. 2018).

The purpose of this review, therefore, was to examine the peer-reviewed research on ableism and employment equity, focusing on how ableism manifests, influences employment outcomes, and intersects with other forms of discrimination while incorporating an intersectional lens to capture the multidimensional relationships between identity, social location, and the lived experiences of disabled employees and jobseekers. The overarching research question guiding this review was the following: “How does ableism affect the experiences of employment for disabled workers and job-seekers?” Sub-questions included the following:

- How does ableism manifest itself in employment contexts (e.g., barriers to employment across the employment cycle, discrimination, workplace culture, and disclosure)?

- How does ableism affect employment outcomes for disabled workers and jobseekers (e.g., pay, rates of employment, workload)?

- What differences exist across various types of disabilities, and how do intersectional factors (e.g., race, gender) influence these experiences?

- What best practices identified in the literature, such as workplace interventions, standards, policies, and legal frameworks, can effectively address ableism in employment and promote inclusion?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

A scoping review of the literature was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMAs) guidelines (Tricco et al. 2018), as well as the framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005). This included systematically searching peer-reviewed databases, applying pre-determined inclusion and exclusion criteria, extracting relevant data, and synthesizing findings thematically to map key concepts, gaps, and areas for future research. This scoping review did not involve a formal review protocol or registration, as its exploratory nature was designed to comprehensively map the breadth of the existing literature without the constraints of a predefined framework.

A literature search strategy was co-developed by all authors and a UBC librarian with feedback from all other authors. Terms such as disab*, disorder, and impairment* were combined with terms such as ableism, discrimination, and barrier*, as well as workplace*, employment, and job* to capture the three main facets of this inquiry: disability, ableism, and employment. Supplementary File S1 provides an example of an electronic search strategy.

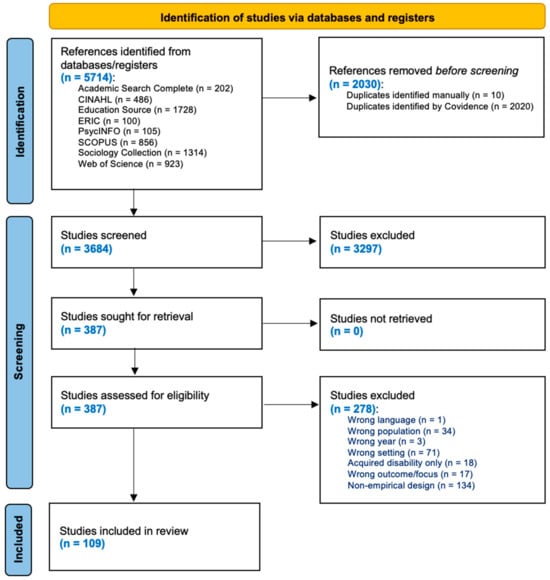

Authors RS and RA conducted searches of articles published from 2018 to 2023 in the following databases: Sociology Collection, CINAHL, PsycInfo, Web of Science, SCOPUS, Education Source, Academic Search Complete, and ERIC. These databases were selected for their relevance to social sciences, interdisciplinary research, and studies examining employment, disability, and workplace equity (Beaudry and Miller 2016; Hughes and Sharp 2021), and articles from before 2018 were not considered to ensure the inclusion of recent and relevant findings reflecting contemporary workplace policies and practices (Bramer et al. 2017). A total of 5714 articles were retrieved. After exporting to an online data management system (Covidence), 2030 duplicate articles were removed, yielding 3684 articles for title and abstract screening.

2.2. Study Selection

The authors RS and RA screened the titles and abstracts of all articles according to pre-determined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies were included if they were peer-reviewed, empirical (i.e., discussed the employment experiences of people with disabilities), conducted in Canada, the United States of America (USA), Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom (UK), Sweden, Norway, Finland, Denmark, or Iceland, and written in English, French, Spanish, or Portuguese (languages spoken fluently by research team members). These specific countries were chosen because their workplace policies and disability inclusion models share similar frameworks, facilitating a cohesive analysis; many of these countries have implemented comparable employment-oriented disability policies (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2022). Non-empirical studies or studies not yet published (e.g., dissertations, literature reviews, preprints), studies that did not focus on employment settings, studies that did not center working-age disability populations, interventional (non-naturalistic) studies, as well as studies not in the abovementioned languages or conducted outside of the above countries were excluded. Complete article inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found below in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for scoping review articles.

Upon completion, 3297 studies were deemed irrelevant, and 387 studies were included in the full-text review. The authors RS and RA then conducted the full-text review process with bi-weekly follow-up from all remaining authors, with 109 articles included for data extraction. All authors remained unblinded to the study and journal characteristics throughout the selection process. Figure 1 illustrates the study selection process, presented as a flow diagram developed in accordance with PRISMA guidelines (Tricco et al. 2018).

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram of study selection process.

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

The authors RS and RA extracted, synthesized, and analyzed data independently using Google Sheets and Adobe Acrobat, with bi-weekly discussions with the rest of the research team throughout the analytic process. Data were extracted in tabulated form and included the following: author/organization, year, research question/aim, country of study, study design, definition of disability, participant characteristics (e.g., age, gender, disability type, sample size, race, recruitment format), data collection details (if applicable), outcome measures, key findings, types of barriers, stages of employment affected, effects on employment outcomes, best practices, impacts of COVID-19 (if applicable), and study limitations. To ensure consistency, only data from the findings and results sections of the studies were included, avoiding the duplication of authors’ interpretations.

Thematic narrative analysis was employed to summarize overarching messages as well as themes categorized by variables such as disability type, stage of employment, gender, race, and other intersectional factors (Levac et al. 2010; Arksey and O’Malley 2005); this method was selected for its ability to amalgamate diverse findings while addressing the complex and multidimensional nature of ableism, which intersects across various employment stages and identities (Levac et al. 2010). The authors RS and RA examined tabulated findings in duplicate to identify relationships and trends, classifying them thematically according to the review’s objectives and synthesizing them narratively to finalize themes and subthemes. Articles were considered to endorse a theme only if they explicitly provided direct evidence of it; when numbers were cited (e.g., “36 articles said X”), they reflected studies explicitly addressing the theme or subtheme, though most demonstrated connections to multiple themes, underscoring the systemic nature of ableism. In addition, due to the scoping nature of this review, study quality was not assessed, as the objective was to identify all relevant studies rather than focus exclusively on high-quality ones (Arksey and O’Malley 2005).

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

The 109 peer-reviewed publications included in this review involved research conducted in a number of countries: eleven in Australia; eight in Canada; one in Denmark; one in Iceland; one in New Zealand; five in Norway; four in Sweden; thirteen in the United Kingdom; sixty-two in the United States; and three in multiple of the above countries. Of these, 8 were mixed methods; 55 were qualitative; and 46 were quantitative. The sample sizes of the qualitative studies ranged from 5 to 137; the sample size of the mixed methods studies ranged from 12 to 1230; and the sample size of the quantitative studies ranged from 60 to 13.8 million.

Regarding the definition of disability type(s) within the following study samples: 16 studies focused on people with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD); 12 looked at Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDDs); 9 focused on mental illnesses or a “psychiatric disability (e.g., depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, etc.); 7 focused on impaired hearing and/or deaf populations; 7 focused on blindness and/or visual impairments; 7 looked at populations with multiple sclerosis (MS); 5 focused on populations with spinal cord injuries; 2 studies looked at samples with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD); 2 specified invisible/non-apparent disabilities; two looked at learning disabilities (LD); and 2 identified mobility impairments (unspecified). Nine studies did not specify the type of disability, fifteen studies specified a “physical disability”, and thirty-eight studies included a sample with multiple disabilities, i.e., more than one of the above-mentioned categories.

Tabulated findings per article are provided in Supplementary File S2, with thematic findings discussed in the narrative format below.

3.2. Impact on Employment Outcomes

Broadly, our search found ableism to significantly and negatively affect employment outcomes, leading to reduced wages, fewer hours, limited opportunities for advancement, and lower employment rates among disabled workers (Ameri et al. 2018; Bendick 2018; Cmar and Steverson 2021; Dolce and Bates 2019; Henly and Brucker 2020; Kim et al. 2020; McDonnall and Crudden 2018), while 12 highlighted reduced wages and hours (Adams et al. 2019; Ballan and Freyer 2020; Booth et al. 2018; Filia et al. 2021; Gupta et al. 2021; Hardonk and Halldórsdóttir 2021; Hedley et al. 2021; Hoque and Bacon 2022; Ostrow et al. 2019; Schur et al. 2020; Sprong et al. 2020; Sundar et al. 2018). Fifteen studies reported how disabled workers are often employed below their qualifications with limited chances for promotion (Carr and Namkung 2021; Dong et al. 2021b; Hampson et al. 2020; Hedley et al. 2021; Heron et al. 2020; Hoque and Bacon 2022; Kim et al. 2020; Kiesel et al. 2019; Madera et al. 2020; McBee-Black and Ha-Brookshire 2018; Meltzer et al. 2019; Plexico et al. 2019; Rumrill et al. 2019; Rustad and Kassah 2020; Silverman et al. 2019). These negative outcomes tend to manifest as a result of four key thematic areas of negative workplace experiences: namely, (1) barriers within or in relation to the work environment; (2) experiences of workplace discrimination; (3) difficulty obtaining appropriate accommodations; and (4) difficulty disclosing one’s disability. Subthemes and examples of the impacts of the above on employment outcomes, as well as nuances across the stages of employment, emergent intersectional factors, and the best-identified practices for fostering equity and inclusion, are discussed below.

3.3. Barriers in Relation to the Work Environment

Clear mentions of employees with disabilities experiencing barriers directly within or in relation to the work environment were provided within 82 articles (Adams et al. 2019; Ameri and Kurtzberg 2022; Ameri et al. 2018; Awsumb et al. 2022; Bend and Priola 2018; Bendick 2018; Black et al. 2019, 2020; Booth et al. 2018; Bosua and Gloet 2021; Bross et al. 2021; Bruyère et al. 2020; Caldwell et al. 2020; Carr and Namkung 2021; Cavanagh et al. 2021; Chordiya 2022; Chowdhury et al. 2022; Cmar and Steverson 2021; Delman and Adams 2022; Devine et al. 2021; Djela 2021; Dolce and Bates 2019; Dong and Mamboleo 2022; Dong et al. 2021b; Durand et al. 2021; Fyhn et al. 2021; Giri et al. 2022; Gobelet and Franchignoni 2006; Graham et al. 2018; Grenawalt et al. 2021; Gupta et al. 2021; Hampson et al. 2020; Hanlon and Taylor 2022; Hardonk and Halldórsdóttir 2021; Hedley et al. 2021; Henly and Brucker 2020; Heron et al. 2020; Holmlund et al. 2020; Hoque and Bacon 2022; Hughes et al. 2021; Inge et al. 2018; Jetha et al. 2019; Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al. 2020; Kiesel et al. 2019; Kim et al. 2020; Krause et al. 2021; Kuznetsova and Bento 2018; Lee et al. 2019; Lemos et al. 2022; Lindsay et al. 2019a; Madera et al. 2020; Mangerini et al. 2020; McBee-Black and Ha-Brookshire 2018; McDonnall and Crudden 2018; McKnight-Lizotte 2018; McMahon et al. 2021; Meltzer et al. 2019; Moloney et al. 2019; Nagib and Wilton 2020; Narenthiran et al. 2022; Östlund and Johansson 2018; Ostrow et al. 2019; Phillips et al. 2019; Plexico et al. 2019; Raymaker et al. 2022; Robertson 2018; Rumrill et al. 2019; Rustad and Kassah 2020; Santuzzi et al. 2019, 2022; Schutz et al. 2021; Schwartz et al. 2022; Shamshiri-Petersen and Krogh 2020; Silverman et al. 2019; Sprong et al. 2020; Stokar and Orwat 2018; Sundar et al. 2018; Svinndal et al. 2020; Teindl et al. 2018; Thompson et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2018; Whelpley et al. 2020). The specific barriers discussed included the following: isolation, exclusion, and differential treatment; negative employer attitudes; challenges with vocational rehabilitation (VR) and career guidance mentorship; employer and colleague lack of awareness about disabilities; communication barriers; transportation barriers; and physical barriers within the workplace.

Isolation, exclusion, and differential treatment were identified as barriers in 36 studies (Awsumb et al. 2022; Bend and Priola 2018; Caldwell et al. 2020; Carr and Namkung 2021; Cavanagh et al. 2021; Chordiya 2022; Chowdhury et al. 2022; Djela 2021; Dong et al. 2021b; Dong and Mamboleo 2022; Giri et al. 2022; Hampson et al. 2020; Hanlon and Taylor 2022; Henly and Brucker 2020; Heron et al. 2020; Hoque and Bacon 2022; Kiesel et al. 2019; Kim et al. 2020; Lee et al. 2019; Madera et al. 2020; Mangerini et al. 2020; McBee-Black and Ha-Brookshire 2018; Meltzer et al. 2019; Moloney et al. 2019; Östlund and Johansson 2018; Ostrow et al. 2019; Plexico et al. 2019; Rumrill et al. 2019; Rustad and Kassah 2020; Santuzzi et al. 2022; Schur et al. 2020; Silverman et al. 2019; Sprong et al. 2020; Sundar et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2018; Whelpley et al. 2020). Participants reported a range of experiences, from difficulty socializing or developing meaningful workplace relationships to complete isolation caused by avoidance from colleagues and supervisors. Disabled employees often felt excluded from workplace activities and decision-making processes (Caldwell et al. 2020; Cavanagh et al. 2021) and were less likely to be considered for promotions or leadership roles (Carr and Namkung 2021; Henly and Brucker 2020). These barriers hindered disabled workers’ ability to engage fully in their roles and advance professionally. Additionally, systemic issues such as limited access to accommodations and support (Awsumb et al. 2022; Dong and Mamboleo 2022; Heron et al. 2020), coordination failures between employers and benefits agencies (Östlund and Johansson 2018; Meltzer et al. 2019), and gender-based expectations—such as women being assigned lower-paid or unpaid tasks—exacerbated inequities for disabled employees (Bend and Priola 2018; Mangerini et al. 2020).

Negative employer attitudes were discussed in 29 articles (Ameri and Kurtzberg 2022; Ameri et al. 2018; Bendick 2018; Black et al. 2020; Bosua and Gloet 2021; Caldwell et al. 2020; Carr and Namkung 2021; Durand et al. 2021; Fyhn et al. 2021; Grenawalt et al. 2021; Gupta et al. 2021; Hardonk and Halldórsdóttir 2021; Heron et al. 2020; Hughes et al. 2021; Jetha et al. 2019; Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al. 2020; Kiesel et al. 2019; Mangerini et al. 2020; McDonnall and Crudden 2018; McMahon et al. 2021; Meltzer et al. 2019; Moloney et al. 2019; Ostrow et al. 2019; Santuzzi et al. 2019; Santuzzi et al. 2022; Schwartz et al. 2022; Sundar et al. 2018; Thompson et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2018). Employer attitudes were defined as conscious or unconscious evaluations by employers based on the actions, feelings, or thoughts that influence subsequent behavior and arise in employment situations (Hardonk and Halldórsdóttir 2021; McDonnall and Crudden 2018); as such, negative employer attitudes are those that adversely impact job applicants and employees (McDonnall and Crudden 2018). These negative attitudes resulted in disabled employees experiencing “othering”, low “belongingness”, or exclusion from work circles; hindered access to and uptake of flexible working arrangements; frequent employer misunderstandings; heightened employer focus on the disability rather than the person; hindered personal relationships and not being “of interest” to the employer compared to relationships with non-disabled employees; difficulty participating in employer–employee meetings, such as performance management and evaluation opportunities, due to lack of interest or communication from the employer and/or employee goals not being prioritized; and limited support and help with day-to-day tasks.

Challenges with vocational rehabilitation (VR) and career guidance mentorship, such as lack of support and poor employment options, were discussed in 29 articles (Caldwell et al. 2020; Chowdhury et al. 2022; Delman and Adams 2022; Devine et al. 2021; Grenawalt et al. 2021; Gobelet and Franchignoni 2006; Gupta et al. 2021; Giri et al. 2022; Hardonk and Halldórsdóttir 2021; Hedley et al. 2021; Heron et al. 2020; Holmlund et al. 2020; Inge et al. 2018; Krause et al. 2021; Kuznetsova and Bento 2018; Lemos et al. 2022; McKnight-Lizotte 2018; Meltzer et al. 2019; Nagib and Wilton 2020; Östlund and Johansson 2018; Phillips et al. 2019; Raymaker et al. 2022; Robertson 2018; Santuzzi et al. 2019; Schutz et al. 2021; Silverman et al. 2019; Sundar et al. 2018; Svinndal et al. 2020; Whelpley et al. 2020). Vocational rehabilitation and career guidance mentorship were found to vary greatly between countries but were generally considered to be government-funded services that help individuals with disabilities overcome barriers to accessing, maintaining, or returning to employment (Gobelet and Franchignoni 2006). A lack of support from VR and career guidance mentors and organizations (Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al. 2020; Meltzer et al. 2019; Nagib and Wilton 2020; Raymaker et al. 2022; Robertson 2018; Schutz et al. 2021; Silverman et al. 2019; Sundar et al. 2018), geographically and socially inaccessible employment options with inadequate mobility and transportation support (Inge et al. 2018; Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al. 2020; Nagib and Wilton 2020; Östlund and Johansson 2018; Sundar et al. 2018; Silverman et al. 2019), and communication challenges within the workplace—stemming from stigma-induced anxiety, unclear instructions, difficulty navigating social norms like break interactions, and workplace bullying—were identified as significant barriers for disabled workers across various disabilities and demographics (Heron et al. 2020; Lemos et al. 2022; McKnight-Lizotte 2018; Östlund and Johansson 2018; Santuzzi et al. 2019; Schutz et al. 2021; Stokar and Orwat 2018; Svinndal et al. 2020; Whelpley et al. 2020).

Employer and colleague lack of awareness about disability was highlighted by 24 articles to be a frequent barrier in the workplace (Awsumb et al. 2022; Black et al. 2020; Booth et al. 2018; Bosua and Gloet 2021; Djela 2021; Dolce and Bates 2019; Dong and Mamboleo 2022; Dong et al. 2021a; Grenawalt et al. 2021; Heron et al. 2020; Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al. 2020; Lee et al. 2019; Lemos et al. 2022; Lindsay et al. 2019a; McDonnall and Crudden 2018; McMahon et al. 2021; Phillips et al. 2019; Santuzzi et al. 2019; Shamshiri-Petersen and Krogh 2020; Stokar 2020; Stokar and Orwat 2018; Teindl et al. 2018; Thompson et al. 2019; Whelpley et al. 2020). Examples of this included employers endorsing stereotypical assumptions about the abilities of disabled workers, such as associating disabilities with lower productivity and higher costs (Fyhn et al. 2021; Shamshiri-Petersen and Krogh 2020); a lack of employer willingness to modify job structures or provide necessary supports (Hardonk and Halldórsdóttir 2021; Svinndal et al. 2020); limited understanding of accommodations and processes to access them (Dong et al. 2021b; Inge et al. 2018); and the systemic undervaluation of disabled workers’ capabilities, particularly for those with invisible disabilities (Grenawalt et al. 2021; Santuzzi et al. 2019).

Communication barriers were cited as being a significant barrier within 14 articles (Black et al. 2019; Black et al. 2020; Bross et al. 2021; Bruyère et al. 2020; Hampson et al. 2020; Hedley et al. 2021; Holmlund et al. 2020; McKnight-Lizotte 2018; Nagib and Wilton 2020; Östlund and Johansson 2018; Schutz et al. 2021; Stokar and Orwat 2018; Svinndal et al. 2020; Whelpley et al. 2020) reported. These communication challenges, including difficulties navigating workplace social norms and empathic misunderstandings, overwhelmingly contributed to the feelings of exclusion and isolation described previously (Dong and Mamboleo 2022; Moloney et al. 2019). As an example, autistic employees face difficulties with social interactions and adapting to communication norms, often leading to misunderstandings with coworkers and supervisors (Black et al. 2019; Black et al. 2020). Anxiety and stress stemming from unclear instructions, limited feedback, and inadequate communication tools hinder workplace performance (McKnight-Lizotte 2018; Östlund and Johansson 2018). Poorly designed interview processes and insufficient systems for disclosing an individual’s communication needs create additional obstacles, particularly during recruitment stages (Bruyère et al. 2020). A lack of employer awareness about accessible communication practices further isolates employees with disabilities, reducing their ability to collaborate effectively (Schutz et al. 2021; Stokar and Orwat 2018).

Transportation barriers were also described as a major barrier within 11 articles (Adams et al. 2019; Awsumb et al. 2022; Cmar and Steverson 2021; Devine et al. 2021; Giri et al. 2022; Graham et al. 2018; Inge et al. 2018; Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al. 2020; Nagib and Wilton 2020; Silverman et al. 2019; Sundar et al. 2018). Inaccessible or unreliable transportation options limit participation in job-related activities (Adams et al. 2019; Giri et al. 2022). A lack of specialized transportation prevents individuals with physical disabilities from attending job interviews or maintaining consistent employment (Graham et al. 2018; Inge et al. 2018). High transportation costs and poor coordination between transit services disproportionately impact rural and lower-income workers as well (Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al. 2020; Sundar et al. 2018).

Physical barriers within the workplace were reported in nine articles (Bend and Priola 2018; Black et al. 2019; Bosua and Gloet 2021; Dong and Mamboleo 2022; Hughes et al. 2021; Krause et al. 2021; Kuznetsova and Bento 2018; Narenthiran et al. 2022; Östlund and Johansson 2018). Inaccessible building layouts, such as narrow hallways and non-automated doors, and insufficient accommodations hinder career progression, particularly for physically disabled women (Bend and Priola 2018). Poor lighting, unsuitable furniture, and limited control over the workspace negatively impact employees, with some preferring to work from home due to these challenges (Narenthiran et al. 2022). Barriers also included inaccessible restroom facilities and restricted access to higher-level floors in multi-story buildings due to outdated elevators or a lack of them (Black et al. 2019). Outdated workplace policies and insufficient training among employers further restrict access to adaptive equipment and accommodations, such as ergonomic furniture and assistive devices (Dong and Mamboleo 2022; Hughes et al. 2021). Additionally, inadequate planning for physical accessibility in telework setups, such as insufficiently adapted home-office equipment, was also found to limit opportunities for remote working and affect productivity (Bosua and Gloet 2021; Kuznetsova and Bento 2018).

3.4. Experiences of Workplace Discrimination

In total, 59 articles found that employees and jobseekers with disabilities experience outright discrimination in the workplace (Ameri et al. 2018; Ballan and Freyer 2020; Bend and Priola 2018; Bendick 2018; Booth et al. 2018; Button 2018; Caldwell et al. 2020; Carolan et al. 2020; Carr and Namkung 2021; Cavanagh et al. 2021; Chowdhury et al. 2022; Cmar and Steverson 2021; Delman and Adams 2022; Djela 2021; Dong et al. 2021b; Dong and Mamboleo 2022; Filia et al. 2021; Friedman and Rizzolo 2020; Giri et al. 2022; Graham et al. 2018, 2019; Grenawalt et al. 2021; Gupta et al. 2021; Hampson et al. 2020; Hayward et al. 2018; Hedlund et al. 2021; Henly and Brucker 2020; Hoque and Bacon 2022; Hughes et al. 2021; Inge et al. 2018; Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al. 2020; Kiesel et al. 2019; Kim et al. 2020; Lee et al. 2019; Leslie et al. 2020; Madera et al. 2020; McDonnall and Crudden 2018; McDonnall and Tatch 2021; McKnight-Lizotte 2018; McMahon et al. 2021; Meltzer et al. 2019; Moloney et al. 2019; Moreland et al. 2022; Østerud 2022b; Ostrow et al. 2019; Phillips et al. 2019; Plexico et al. 2019; Raymaker et al. 2022; Robertson 2018; Romualdez et al. 2021a, 2021b; Rumrill et al. 2019; Rustad and Kassah 2020; Santuzzi et al. 2019; Schutz et al. 2021; Shamshiri-Petersen and Krogh 2020; Silverman et al. 2019; Teindl et al. 2018; Thompson et al. 2019; Whelpley et al. 2020).

Though discriminatory experiences took place in all parts of the job cycle, they appeared to occur most frequently during the hiring process when compared to other categories of the job cycle, as found in 20 articles (Ameri et al. 2018; Ballan and Freyer 2020; Bendick 2018; Grenawalt et al. 2021; Hampson et al. 2020; Hayward et al. 2018; Henly and Brucker 2020; Kiesel et al. 2019; McDonnall and Crudden 2018; McDonnall and Tatch 2021; McKnight-Lizotte 2018; McMahon et al. 2021; Moloney et al. 2019; Moreland et al. 2022; Robertson 2018; Romualdez et al. 2021b; Schutz et al. 2021; Shamshiri-Petersen and Krogh 2020; Teindl et al. 2018; Whelpley et al. 2020). In these studies, employers frequently preferred non-disabled candidates, citing concerns about productivity and accommodation costs, and participants across studies described challenges such as inaccessible recruitment processes, employer biases, and lack of accommodations during interviews. Individuals with disabilities faced a lower likelihood of being hired compared to non-disabled applicants, compounded by intersectional barriers such as exclusion from interviews for those with visible developmental disabilities, difficulties navigating hiring and workplace environments for individuals with high autistic traits, and challenges maintaining employment for those with invisible disabilities (Ameri et al. 2018; Hayward et al. 2018; Henly and Brucker 2020; Schutz et al. 2021; Teindl et al. 2018).

Bullying and microaggressions were described in 16 studies (Chowdhury et al. 2022; Delman and Adams 2022; Djela 2021; Dong et al. 2021b; Giri et al. 2022; Hampson et al. 2020; Hedlund et al. 2021; Inge et al. 2018; Lee et al. 2019; Leslie et al. 2020; Madera et al. 2020; Meltzer et al. 2019; Raymaker et al. 2022; Romualdez et al. 2021b; Rumrill et al. 2019; Santuzzi et al. 2019), contributing to feelings of inadequacy, exclusion, heightened stress, social isolation, and reduced job satisfaction (Chowdhury et al. 2022; Djela 2021). Microaggressions were categorized as microassaults, microinsults, or microinvalidations in these studies: microassaults included overt hostility, such as mocking assistive device use (Raymaker et al. 2022); microinsults involved subtle, dismissive remarks about accommodations (Hampson et al. 2020); and microinvalidations downplayed disabilities, e.g., “You don’t seem disabled” (Romualdez et al. 2021b). Customer discrimination also emerged as a barrier, with employees with disabilities receiving lower competence ratings and being unfairly blamed for service failures (Madera et al. 2020).

Job loss due to employer discrimination was discussed in 16 studies (Bendick 2018; Booth et al. 2018; Carolan et al. 2020; Carr and Namkung 2021; Djela 2021; Filia et al. 2021; Graham et al. 2019; Gupta et al. 2021; Hampson et al. 2020; Kiesel et al. 2019; Leslie et al. 2020; Raymaker et al. 2022; Robertson 2018; Rumrill et al. 2019; Santuzzi et al. 2019; Schutz et al. 2021), often resulting from employer biases, inadequate accommodations, or stereotypes about worker abilities. Even without explicit discrimination, job loss frequently stemmed from ableism, with individuals citing dismissal, resignation, or medical retirement due to illness management challenges (Booth et al. 2018) or stigma surrounding mental health-related absenteeism (Filia et al. 2021). For example, individuals with systemic lupus erythematosus frequently cited medical dismissal or resignation due to illness management (Booth et al. 2018), while those with bipolar disorder reported stigma-related job loss tied to absenteeism (Filia et al. 2021). Workers with visible and invisible developmental disabilities struggled to maintain employment due to insufficient workplace support (Robertson 2018; Teindl et al. 2018). Beyond financial instability, job loss contributed to stress, reduced self-esteem, exclusion, and barriers to re-employment, exacerbating its impact on mental health and future job prospects (Rumrill et al. 2019; Raymaker et al. 2022).

Diminished workplace advancement due to biases about abilities was described in nine studies (Booth et al. 2018; Cavanagh et al. 2021; Delman and Adams 2022; Gupta et al. 2021; Hoque and Bacon 2022; Phillips et al. 2019; Plexico et al. 2019; Rumrill et al. 2019; Rustad and Kassah 2020). For example, in these studies, employees with physical disabilities were often perceived as less capable, limiting their opportunities for recognition (Cavanagh et al. 2021), while those with developmental disabilities were confined to low-skill roles despite demonstrating competency (Booth et al. 2018). Discrimination in performance evaluations, exclusion from mentorship, and a lack of accommodations further restricted advancement, such as workers with speech disabilities being excluded from incentives (Plexico et al. 2019).

3.5. Difficulty Obtaining Workplace Accommodations

Difficulty obtaining workplace accommodations was a key theme found in 27 studies (Ameri and Kurtzberg 2022; Bend and Priola 2018; Bosua and Gloet 2021; Caldwell et al. 2020; Carolan et al. 2020; Chandola and Rouxel 2021; Chowdhury et al. 2022; Djela 2021; Dong et al. 2021a, 2021b; Dong and Mamboleo 2022; Durand et al. 2021; Fyhn et al. 2021; Graham et al. 2018; Gupta et al. 2021; Hanlon and Taylor 2022; Heron et al. 2020; Hughes et al. 2021; Inge et al. 2018; Jetha et al. 2019; Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al. 2020; Kuznetsova and Bento 2018; Leslie et al. 2020; Lindsay et al. 2019a; McBee-Black and Ha-Brookshire 2018; Moreland et al. 2022; Sundar et al. 2018). Challenges span the process of requesting accommodations, receiving them once requested, and navigating bureaucratic obstacles.

Challenges upon successfully receiving accommodations once requested were detailed in 19 studies (Chandola and Rouxel 2021; Chowdhury et al. 2022; Djela 2021; Durand et al. 2021; Gupta et al. 2021; Holmlund et al. 2020; Hughes et al. 2021; Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al. 2020; Kuznetsova and Bento 2018; Leslie et al. 2020; Lindsay et al. 2019a; McBee-Black and Ha-Brookshire 2018; Robertson 2018; Rumrill et al. 2019; Schwartz et al. 2022; Stokar and Orwat 2018; Sundar et al. 2018; Teindl et al. 2018; Whelpley et al. 2020). Participants described delays, partial fulfillment, or the outright denial of accommodations. For instance, employees requiring assistive technology often face month-long delays due to insufficient internal processes (Durand et al. 2021). In other cases, workers were provided accommodation that did not meet their specific needs, leaving them unsupported (Leslie et al. 2020; Robertson 2018).

However, many individuals never even received the accommodations outlined above. Indeed, challenges requesting accommodations were highlighted in 11 studies (Ameri and Kurtzberg 2022; Carolan et al. 2020; Dong et al. 2021a, 2021b; Dong and Mamboleo 2022; Graham et al. 2018; Hanlon and Taylor 2022; Inge et al. 2018; Mangerini et al. 2020; Moloney et al. 2019; Stokar 2020). Negative reactions from employers and coworkers created significant barriers to initiating accommodation requests. Participants frequently reported dismissive or skeptical responses when seeking accommodations, such as modified work schedules or ergonomic adjustments (Dong et al. 2021b). Fear of stigma and discrimination, particularly for those with invisible disabilities, compounded these challenges, leading many to avoid asking for support altogether (Hanlon and Taylor 2022). Workers described anxiety and guilt about burdening their employers, with some perceiving that requests for accommodations might jeopardize their jobs; these fears were exacerbated by employers’ lack of understanding or compassion regarding disability needs (Graham et al. 2018).

The above challenges were frequently related to bureaucratic barriers to receiving accommodations, as reported in eight studies (Bosua and Gloet 2021; Dong and Mamboleo 2022; Heron et al. 2020; Jetha et al. 2019; Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al. 2020; Kuznetsova and Bento 2018; Moreland et al. 2022; Phillips et al. 2019). These included a lack of clear policies, limited managerial knowledge of disability support, and insufficient corporate resources. For example, some noted that their employers lacked a formal process for requesting accommodation, which led to confusion and delays (Phillips et al. 2019). Others identified structural issues, such as inadequate funding or training for HR staff to handle accommodations effectively (Kuznetsova and Bento 2018).

3.6. Difficulty with Disability Disclosure

A total of 45 articles addressed challenges with disability disclosure, highlighting its association with negative outcomes, such as wage gaps, reduced hiring potential, and the increased likelihood of dismissal (Ameri and Kurtzberg 2022; Bend and Priola 2018; Black et al. 2020; Booth et al. 2018; Bross et al. 2021; Bruyère et al. 2020; Button 2018; Chordiya 2022; Djela 2021; Dolce and Bates 2019; Dong and Mamboleo 2022; Friedman 2019; Graham et al. 2018; Grenawalt et al. 2021; Gupta et al. 2021; Hampson et al. 2020; Hedley et al. 2021; Henly and Brucker 2020; Hoque and Bacon 2022; Hughes et al. 2021; Jarus et al. 2019; Jetha et al. 2019; Kiesel et al. 2019; Kim et al. 2020; Kuznetsova and Bento 2018; Lee et al. 2019; Lindsay et al. 2019a; McDonnall and Tatch 2021; McMahon et al. 2021; Moloney et al. 2019; Østerud 2022b; Ostrow et al. 2019; Phillips et al. 2019; Raymaker et al. 2022; Robertson 2018; Romualdez et al. 2021a, 2021b; Rustad and Kassah 2020; Santuzzi et al. 2019; Schwartz et al. 2022; Sprong et al. 2020; Sundar et al. 2018; Teindl et al. 2018; Thompson et al. 2019; Whelpley et al. 2020). Many studies did not specify the types of disabilities in their samples, making it challenging to draw nuanced conclusions about disclosure experiences (Button 2018; Chordiya 2022; Friedman 2019; Hoque and Bacon 2022; Kim et al. 2020; Kuznetsova and Bento 2018; Sprong et al. 2020).

Workers with invisible disabilities, such as ADHD, ASD, and mental illnesses, face compounded barriers both when disclosing and when choosing not to disclose their disability, often fearing being seen as “failing” if they do not disclose their disability (Moloney et al. 2019; Lindsay et al. 2019a). Mental illnesses like schizophrenia and psychosis are particularly stigmatized, with workers often perceived as “unprofessional” when disclosing their disability too early or encouraged to attribute their conditions to external causes (Østerud 2022b). Similarly, autistic workers in North America were less likely to prioritize disclosure compared to their counterparts in Europe or Australia, reflecting cultural differences (Black et al. 2020). Jobseekers with ASD often face criticism during interviews for incomplete answers or difficulty interpreting social cues, which employers misinterpret as performance deficits (Bruyère et al. 2020). In general, coworkers and employers frequently dismiss invisible disabilities as exaggerated or unimportant, further isolating workers (Ameri and Kurtzberg 2022; Hughes et al. 2021; Thompson et al. 2019).

In contrast, visible disabilities were more frequently disclosed in these studies, as workers often sought accommodations for mobility or sensory impairments, though stigma and inadequate employer knowledge still posed significant barriers (Dong and Mamboleo 2022; Lindsay et al. 2019a). Workers with musculoskeletal disorders or visual impairments disclosed their disability to gain necessary adjustments but faced a limited understanding of their needs (Lindsay et al. 2019a). Visual impairments and ADHD were specifically and notably associated with hiring exclusions upon disclosure (McMahon et al. 2021; McDonnall and Tatch 2021). Despite these challenges, many workers disclosed their disabilities to foster understanding among colleagues and gain accommodations, though these intentions were often undermined by workplace stigma and insufficient policies (Hampson et al. 2020; Schwartz et al. 2022).

3.7. Nuances Across Various Stages of Employment

How ableism manifests in practice was found to differ across the various stages of employment. Within the recruitment stage of employment, disabled jobseekers were found to face barriers such as perceived discrimination, feeling unemployable, transportation challenges, a lack of inclusive opportunities, insufficient qualifications, and difficulty securing interviews (Cmar and Steverson 2021; Giri et al. 2022; Hanlon and Taylor 2022; Hedley et al. 2021; Nagib and Wilton 2020; Robertson 2018). For instance, inaccessible transportation often prevents individuals with physical disabilities from attending interviews, while hiring practices for those with IDDs emphasize limitations over strengths (Nagib and Wilton 2020; Robertson 2018).

During hiring, disabled jobseekers face lower hiring rates in these studies due to employer biases, including perceptions of lower productivity or higher costs (McMahon et al. 2021; Shamshiri-Petersen and Krogh 2020) or viewing late disability disclosure as deceptive and early disclosure as unprofessional (Østerud 2022b). Employers’ unawareness about disabilities and disabled workers’ contributions further exacerbates these barriers (Grenawalt et al. 2021).

At the employee integration stage, accommodation challenges dominated, with managers often unprepared to provide flexible arrangements like accessible offices or IT support (Bosua and Gloet 2021). Disability-related needs, such as fatigue or mobility issues, are frequently trivialized as excuses for underperformance (Hedlund et al. 2021). Disabled employees also reported exclusion from social events alongside invalidating remarks from coworkers and employer mistrust, especially in remote roles (Djela 2021; Lee et al. 2019; Santuzzi et al. 2022).

Finally, during performance management, barriers mirror those in integration and include inadequate accommodations, stigma, and limited opportunities for advancement. Disabled workers in these studies reported lower satisfaction and pay compared to non-disabled peers (Friedman and Rizzolo 2020; Hoque and Bacon 2022; Narenthiran et al. 2022). Workers described reduced task control, greater employer interference, and difficulties balancing work and home life (Narenthiran et al. 2022). The absence of clear organizational policies addressing accommodations, wages, and benefits, combined with poor communication between VR mentors, insurers, and other supports, exacerbate these challenges (Östlund and Johansson 2018).

Many disabled jobseekers never advance to any stage of employment, as highlighted in 11 articles (Adams et al. 2019; Awsumb et al. 2022; Bross et al. 2021; Cmar and Steverson 2021; Hardonk and Halldórsdóttir 2021; Kim et al. 2020; McBee-Black and Ha-Brookshire 2018; Meltzer et al. 2019; Nagib and Wilton 2020; Sevak et al. 2018; Schutz et al. 2021). Those with IDDs face particularly high unemployment and limited opportunities (Adams et al. 2019; Awsumb et al. 2022). Disabled youth struggle to secure competitive roles due to inadequate qualifications and training (Cmar and Steverson 2021). Prolonged unemployment, the undervaluation of disabled workers, systemic biases, and resistance to accommodations further restrict access to meaningful employment (Meltzer et al. 2019; Schutz et al. 2021), with intersectional factors like gender and disability compounding barriers to higher-paying roles or promotions (Kim et al. 2020).

3.8. Intersectional Findings

Only 22 studies explicitly defined the term disability, and the same number addressed intersectionality by discussing identity markers like gender, race/ethnicity, or sexuality alongside ability and disability. Most studies lacked participant race/ethnicity data, and among those that reported it, participants were predominantly White. Similarly, gender was typically reported as binary, with most studies split evenly between male and female participants; only seven studies included nonbinary, trans, or non-disclosing participants (Ameri and Kurtzberg 2022; Black et al. 2020; Booth et al. 2018; Krause et al. 2021; Ostrow et al. 2019; Romualdez et al. 2021a; Silverman et al. 2019). Separately, a specific barrier that female workers face is being forced to conform to gender roles, e.g., not being taken seriously when seeking support or advocacy, having poor mental health or mental illness trivialized or attributed to personality, receiving less education and benefits when compared to male workers, and being forced to uptake unpaid labor unrelated to their job positions without appropriate compensation, such as childcare, cleaning, irrelevant administrative duties, making coffee, and others’ roles and responsibilities (Ballan and Freyer 2020; Hedlund et al. 2021; Mangerini et al. 2020).

Generally, we found that disabled minority workers marginalized by race, ethnicity, sex, gender, or age faced heightened discrimination, lower employment rates, and fewer opportunities for advancement compared to the general disabled population, as highlighted by 15 studies (Bend and Priola 2018; Carolan et al. 2020; Carr and Namkung 2021; Chordiya 2022; Chowdhury et al. 2022; Delman and Adams 2022; Durand et al. 2021; Gupta et al. 2021; Henly and Brucker 2020; Kiesel et al. 2019; Kim et al. 2020; Nagib and Wilton 2020; Raymaker et al. 2022; Rumrill et al. 2019; Schur et al. 2020). For instance, female workers experience poorer occupational outcomes than male workers, including limited opportunities for higher-paying roles and promotions (Kim et al. 2020). We also noted that visible disabilities, such as IDDs, often led to difficulties in securing employment, whereas invisible disabilities, like ADHD, were associated with challenges in maintaining jobs, disclosing disabilities, and receiving adequate workplace support (Teindl et al. 2018; Kiesel et al. 2019; Bend and Priola 2018; Hughes et al. 2021). The severity of disability also impacts employment, with less severe disabilities doubling the likelihood of employment compared to more severe disabilities, as evidenced by persistently low employment rates among individuals with developmental disabilities (Nagib and Wilton 2020).

3.9. Best Practices

Three key areas of best practice were endorsed across the studies. First, the importance of increased education and training to improve knowledge of various disabilities was endorsed by 34 studies (Adams et al. 2019; Ameri and Kurtzberg 2022; Bend and Priola 2018; Bendick 2018; Black et al. 2020; Bosua and Gloet 2021; Bruyère et al. 2020; Djela 2021; Dolce and Bates 2019; Dong and Mamboleo 2022; Friedman 2019; Fyhn et al. 2021; Graham et al. 2018; Grenawalt et al. 2021; Gupta et al. 2021; Hampson et al. 2020; Hanlon and Taylor 2022; Hardonk and Halldórsdóttir 2021; Hedley et al. 2021; Heron et al. 2020; Iwanaga et al. 2018; Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al. 2020; Kiesel et al. 2019; Lee et al. 2019; Lemos et al. 2022; Lindsay et al. 2019b; McMahon et al. 2021; Phillips et al. 2019; Plexico et al. 2019; Robertson 2018; Romualdez et al. 2021a, 2021b; Teindl et al. 2018; Whelpley et al. 2020). Specifically, education efforts targeted at employers, coworkers, and the general public were emphasized as crucial for reducing stigma and addressing employer concerns about hiring individuals with disabilities. Examples of workplace-sponsored programs included disability-awareness training, psychoeducation on the traits and needs of specific disabilities, and strength-based training to challenge misconceptions (Hampson et al. 2020; Hanlon and Taylor 2022; Teindl et al. 2018). Public education initiatives, such as inclusive school programs to counter stereotypes early, were also recommended (Hampson et al. 2020). Articles further highlighted community-based support, including mentorship programs, partnerships with schools and youth centers, employer outreach programs, collaboration with disability organizations, and inclusion campaigns. For instance, hosting disability conferences or having representatives from mental health organizations train employees were cited as effective strategies for fostering understanding and inclusivity (Lindsay et al. 2019b).

Second, the need for individualized training and accommodations to improve the work environment and simplify procedures for requesting accommodations was endorsed by 37 studies (Bend and Priola 2018; Black et al. 2019; Booth et al. 2018; Bross et al. 2021; Bruyère et al. 2020; Caldwell et al. 2020; Carolan et al. 2020; Dong and Mamboleo 2022; Durand et al. 2021; Filia et al. 2021; Graham et al. 2019; Hanlon and Taylor 2022; Hayward et al. 2018; Hernández González 2021; Hughes et al. 2021; Inge et al. 2018; Jetha et al. 2019; Kiesel et al. 2019; Kuznetsova and Bento 2018; Lemos et al. 2022; Lindsay et al. 2019a, 2019b; Moreland et al. 2022; Nagib and Wilton 2020; Narenthiran et al. 2022; Østerud 2022b; Phillips et al. 2019; Robertson 2018; Romualdez et al. 2021a, 2021b; Rustad and Kassah 2020; Santuzzi et al. 2019; Schwartz et al. 2022; Stokar and Orwat 2018; Sundar et al. 2018; Svinndal et al. 2020; Whelpley et al. 2020). Flexible and open communication between employers and disabled employees was emphasized as key to successful accommodations. Supportive accommodations identified in the literature include “soft” accommodations like flexible schedules, shorter shifts, frequent breaks, remote working options, and tailored training such as buddy systems or neurodiverse-trained staff. Adaptations to interview processes, such as reducing the number of interviewers, were also highlighted (Jetha et al. 2019; Lindsay et al. 2019b). Additionally, “hard” accommodations like accessible software, ergonomic furniture, visual aids, and lighting or noise adjustments were found to enhance workplace inclusivity (Jetha et al. 2019; Lindsay et al. 2019b). Across the studies, workplace accommodations, employer knowledge about disabilities, and employer support were consistently identified as the most critical facilitators for positive employment outcomes (Holmlund et al. 2020; Iwanaga et al. 2018; Kuznetsova and Bento 2018; Kwon 2021; Mangerini et al. 2020; McKnight-Lizotte 2018; McMahon et al. 2021; Phillips et al. 2019; Robertson 2018; Rustad and Kassah 2020; Schwartz et al. 2022; Silverman et al. 2019; Stokar and Orwat 2018; Sundar et al. 2018; Westoby and Shevellar 2019; Whelpley et al. 2020). Moreover, organizations that demonstrated inclusive practices towards people with disabilities experienced a positive increase in their stock price, while discrimination had a negative impact (Hernández González 2021).

Finally, improving government-funded vocational rehabilitation (VR) and mentorship services was discussed in 33 studies, emphasizing the importance of individualized, disability-specific guidance and training tailored to interests, goals, and skills (Adams et al. 2019; Awsumb et al. 2022; Ballan and Freyer 2020; Bishop and Rumrill 2021; Black et al. 2020; Caldwell et al. 2020; Dong and Mamboleo 2022; Ethridge et al. 2020; Friedman and Rizzolo 2020; Fyhn et al. 2021; Graham et al. 2018; Grenawalt et al. 2021; Hampson et al. 2020; Hardonk and Halldórsdóttir 2021; Hayward et al. 2018; Heron et al. 2020; Henly and Brucker 2020; Hughes et al. 2021; Inge et al. 2018; Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al. 2020; Kiesel et al. 2019; Lee et al. 2019; Lindsay et al. 2019b; McDonnall and Crudden 2018; McKnight-Lizotte 2018; Meltzer et al. 2019; Moreland et al. 2022; Nagib and Wilton 2020; Phillips et al. 2019; Plexico et al. 2019; Schutz et al. 2021; Silverman et al. 2019; Svinndal et al. 2020). Key recommendations included training initiatives such as social skill-based interview coaching for jobseekers with ASD, raising awareness about financial aid and pre-employment transition services through schools and community centers, and providing tailored career advice for disabled high school students based on disability and geographic needs. Additionally, establishing intermediaries between employers and jobseekers was proposed to address knowledge gaps surrounding the accommodations, policies, procedures, and external resources (Fyhn et al. 2021). These approaches aim to enhance the accessibility and efficacy of VR services and mentorship programs, fostering a smoother transition into meaningful employment for disabled individuals.

4. Discussion

The current review highlights persistent ableism within employment contexts, emphasizing the significant barriers and inequities faced by disabled workers and jobseekers. Across all stages of the employment cycle, disabled individuals experience systemic discrimination, exclusion, and inadequate accommodations. During recruitment, jobseekers face obstacles such as perceived discrimination, inaccessible processes, geographic and transportation barriers, and a lack of inclusive hiring practices that emphasize strengths rather than limitations. Employers frequently hold prejudiced views about the capabilities of disabled workers, particularly those with developmental or severe disabilities, further limiting employment opportunities. In the hiring stage, the disclosure of disabilities, whether early or late, commonly results in negative perceptions, reduced opportunities, and employer hesitancy, compounded by insufficient awareness of disability-related needs and inclusive practices.

During employee integration and performance management, the inability to obtain necessary accommodations remains a critical issue, driven by bureaucratic challenges, limited employer knowledge, unprepared managers, and fears of stigma or retaliation. Disabled employees also report exclusion from workplace activities, invalidating comments from colleagues, and reduced trust from supervisors, particularly in remote or hybrid working environments. These barriers contribute to lower job satisfaction, reduced workplace inclusion, and inequitable outcomes, such as wage gaps, diminished advancement opportunities, and a higher likelihood of job loss. Transportation challenges, poor coordination among support services, and organizational resistance to accommodations further restrict access to meaningful employment.

Our findings also reveal nuanced experiences shaped by intersecting identities and disability types. Workers with invisible disabilities, such as mental illnesses or neurodevelopmental conditions, such as ADHD, often face unique barriers due to skepticism, stigma, trivialization, or misunderstandings, making disclosure and access to support particularly fraught. In contrast, visible disabilities may be more readily acknowledged but are still subject to systemic barriers, such as inaccessible infrastructure and inadequate workplace policies, highlighting how these hierarchies of perception translate into workplace inequities (Bonaccio et al. 2020). Intersectional factors, such as gender, race, ethnicity, and the severity of disability, compound these barriers, with women, BIPOC, and older workers facing disproportionately poorer outcomes. The pervasiveness of ableism underscores the urgent need for targeted inclusive practices, comprehensive policy reform, and an intersectional approach to addressing employment inequities for disabled individuals.

4.1. Significance and Implications of Findings

The inequities highlighted in this review have profound societal implications. Ableism and the stigmatization of disabilities, particularly invisible ones, reflect deep cultural and institutional biases that obstruct workplace equity (Clair et al. 2021). The systemic undervaluation of disabled workers limits these individual’s economic independence and career progression, deprives organizations of the unique skills and perspectives they bring, and perpetuates cycles of poverty and exclusion through higher unemployment rates, wage gaps, and restricted mobility (Chan and Hutchings 2023; Chis 2024). These ideological hierarchies, rooted in able-bodied norms, privilege certain disabilities over others, often devaluing those disabilities that are less visible, less “understood”, or socially stigmatized. For instance, while physical disabilities appear more likely to elicit tangible accommodations, individuals with cognitive or psychosocial disabilities are often met with dismissal, skepticism, or accusations of exaggeration (Clair et al. 2021). Such dynamics create stratified levels of access, inclusion, and respect, reinforcing oppression based on perceptions of “deservingness” and “legitimacy”. This stratification extends to intersecting identities: BIPOC disabled workers often experience compounded discrimination where ableism intersects with systemic racism, leading to unique barriers in hiring, retention, and workplace culture (Hedley et al. 2021). For example, disabled women may face heightened scrutiny in traditionally male-dominated fields, where both sexism and ableism converge to challenge their credibility and opportunities for advancement (Chan and Hutchings 2023); similarly, transgender individuals with disabilities often encounter layers of marginalization, as both their gender identity and disability status intersect to amplify discrimination and exclusion, particularly in rigid, binary work environments (Harrison et al. 2012). In summary, social practices within the workplace, such as the process of requesting accommodations, the framing of disability disclosure as a “burden”, or the unequal distribution of flexibility, both reflect and reproduce these hierarchies of oppression.

Without accounting for how these overlapping identities are embedded within workplace dynamics and broader societal ideologies, workplace policies and practices risk perpetuating exclusion, leaving the most marginalized individuals behind. Indeed, frameworks of intersectionality, initially conceptualized by Kimberlé Crenshaw to describe how systems of oppression overlap and create unique experiences of discrimination, are rarely applied beyond demographic categorizations in the literature (Crenshaw 1989). As a result, issues like the employment barriers faced by nonbinary or transgender workers with disabilities remain underexplored, and race is frequently reduced to a binary of minority versus non-minority, erasing the complexities of cultural and geographic nuances. This reductionist approach limits the applicability of existing research and reinforces systemic exclusions within employment contexts. Addressing these issues requires a shift in organizational and societal attitudes, the adoption of intersectional, equity-focused frameworks, and the active dismantling of structural barriers to create inclusive and equitable work environments.

4.2. Recommendations for Practice

These findings reveal a pressing need for multi-level interventions to create equitable employment conditions for disabled individuals. At the micro and mezzo levels, organizations and employers must adopt inclusive and proactive practices to address ableism and improve workplace accessibility. Such practices include increasing recruitment efforts for disabled workers, providing structured and culturally sensitive disability training for all occupational levels, and ensuring that workplace accommodations, e.g., flexible schedules and remote work options, are accessible and consistently implemented (Dong et al. 2021b; Phillips et al. 2019). Disabled workers thrive in environments with fixed processes for disclosure and accommodation requests, job shadowing and coaching opportunities, and strong mentorship networks. Collaboration with disability advocacy organizations and the integration of disabled workers into policy development processes are crucial in addressing systemic barriers and fostering inclusion (Bend and Priola 2018; Ethridge et al. 2020). Organizations should also prioritize creating an inclusive culture by actively disrupting biases through ongoing training, transparent communication, and adherence to disability-related policies and laws (Hanlon and Taylor 2022). Disabled workers report greater confidence and acceptance in workplaces that promote accessibility and accommodate intersectional needs. Therefore, organizations must embed intersectional practices into their operations. This can include addressing how race, gender, and other identities interact with disability in shaping workplace experiences. Practices such as accessible mentoring programs and structured feedback mechanisms can enhance employee support networks while reducing workplace biases (Hampson et al. 2020). Employers must recognize that fostering an inclusive workplace culture requires not only compliance with laws but active measures to exceed these standards, promoting equal opportunities and representation for disabled workers (Phillips et al. 2019).

At the macro level, regional, national, and international policies must address structural inequities. Early education systems must challenge negative stereotypes surrounding disability, race, and gender, fostering more inclusive societal attitudes from a young age (Hampson et al. 2020). Mandatory government-sponsored education programs for employers, alongside vocational mentoring and training networks, should emphasize the benefits of diversity and inclusion while highlighting the skills and contributions of disabled workers (Hanlon and Taylor 2022). Policies must also account for the unique barriers faced by intersectional groups, e.g., BIPOC women with disabilities, by integrating their needs into organizational, regional, and national frameworks for recruitment, performance management, and accessibility (Ethridge et al. 2020; Hanlon and Taylor 2022).

4.3. Future Research

Future research must adopt more inclusive and critical methodologies to better outline the intersectional experiences of disabled workers and jobseekers. This requires integrating diversity across dimensions such as gender identity, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, class, disability type, and geographic location. Embracing an intersectional lens could deepen our understanding of how different identities interact to shape unique challenges and opportunities in employment contexts. For instance, examining the compounded barriers faced by BIPOC women with disabilities versus white men with physical disabilities could enable more targeted interventions in policy and practice. Second, this review also highlights a significant gap in understanding differential experiences across disabilities. Many studies default to generalizing “disability” without explicitly defining the scope, often prioritizing physical disabilities. Future research must address this bias by exploring the distinct barriers and opportunities associated with disability visibility. For example, disclosure experiences may differ vastly between individuals with visible disabilities, such as mobility impairments, and those with invisible conditions like ADHD. Indeed, ADHD, despite being a more common disability (National Institute of Mental Health 2022), remains surprisingly underexplored in workplace research, particularly regarding its impact on job retention and accommodations; investigating why ADHD and similar disorders are underrepresented in employment research and addressing this gap could offer valuable opportunities to support neurodivergent workers. Third, the role of external crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, in exacerbating employment inequities for disabled workers warrants urgent investigation. While the pandemic disproportionately impacted disabled individuals, including increased job losses and diminished access to remote working accommodations (Ne’eman and Maestas 2022), these dynamics remain underexplored. Future studies should specifically analyze how workplace adjustments during crises, such as transitions to hybrid or remote working, influence long-term employment outcomes for disabled populations and whether these changes address or reinforce systemic ableism. Fourth, longitudinal research is crucial to understanding the evolving experiences of disabled workers over time. Studies tracking employment trajectories, the sustainability of accommodations, and the long-term impacts of disclosure decisions could reveal how systemic barriers persist or change across different career stages. Next, comparative research across countries could also provide valuable insights, particularly by examining how policy frameworks, cultural attitudes, and economic structures influence employment outcomes for disabled workers in different regions. For instance, contrasting the experiences of disabled employees in countries with robust social support systems, like Sweden, versus those with more market-driven economies, like the United States, could illuminate the best practices and areas for improvement. Finally, researchers should adopt precise, inclusive, and culturally sensitive language within their study design and dissemination to reduce stereotypes and enhance clarity. Addressing these gaps will advance the field toward a more comprehensive understanding of disability in the workplace and inform more equitable policy and practice.

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

This review’s primary strength lies in its comprehensive scope, encompassing a wide range of recent studies on ableism. The scoping review methodology allowed for diverse findings across various methodologies, capturing a broad spectrum of experiences and barriers faced by disabled workers. Analyzing studies from multiple countries with similar policy frameworks provided a degree of generalizability, enhancing relevance for international applications. The inclusion of a broad research question, supported by sub-questions, enabled an expansive exploration of themes and established a robust knowledge base on workplace ableism. Finally, the identification of nuances across different disability types and intersecting identities is a key strength.

However, this review also has limitations. The interrelated nature of themes and the vast number of articles reviewed necessitated a high-level reporting of findings, potentially overlooking specific nuances within individual studies. The purpose of the review was to establish a foundational understanding rather than systematically evaluate each article in depth, meaning that a systematic review would be required to provide more granular insights. The exclusion of gray literature may have omitted valuable insights from non-peer-reviewed sources, such as policy briefs or community-based reports. This review did not address the unique impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on disabled workers despite including studies from this period—a notable gap given the pandemic’s significant disruption to employment and accommodations for disabled populations (Ne’eman and Maestas 2022). Additionally, focusing solely on peer-reviewed academic literature may have excluded the perspectives of disabled individuals as captured through participatory or community-driven research, potentially overlooking valuable insights from those directly affected (Stack and McDonald 2014). Future work should address these gaps to build on this review’s findings and foster a more inclusive understanding of ableism in employment.

5. Conclusions

The current scoping review highlights the systemic barriers faced by disabled individuals in employment, including discrimination, inadequate accommodations, stigmatization, and exclusion across recruitment, hiring, integration, and advancement. These challenges, compounded by intersectional factors such as gender, race, and disability type, perpetuate inequities, restrict economic opportunities, and reinforce workplace marginalization. Given this, research and practice must employ an intersectional critical disability lens when exploring and creating inclusive policies, practices, and forms of education to alleviate the impacts of ableism.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/socsci14020067/s1. Supplementary File S1 contains Table S1: Example of a literature search strategy from PsycInfo. Supplementary File S2 contains Table S2: Literature review article characteristics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.H.S., R.A., R.H. and T.S.; methodology, R.H.S., R.A., R.H. and T.S.; software, R.H. and T.S.; validation, R.H.S. and R.A.; formal analysis, R.H.S. and R.A.; investigation, R.H.S. and R.A.; resources, R.H. and T.S.; data curation, R.H.S. and R.A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.H.S.; writing—review and editing, R.H.S., R.A., R.H. and T.S.; visualization, R.H.S.; supervision, R.H. and T.S.; project administration, R.H. and T.S.; funding acquisition, R.H. and T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the British Columbia Office of the Human Rights Commissioner (BCOHRC)—no specific grant number.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Review board approval was not applicable to this study as it did not involve humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent is not applicable to this study, which did not involve humans.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study (article characteristics) are included in the article/Supplementary Materials (Supplementary File S2). Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We respectfully acknowledge that this research was conducted on the traditional, ancestral, unceded lands of the Syilx (Okanagan) peoples (Kelowna), and the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waituth peoples (Vancouver).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adams, Chithra, Amanda Corbin, Luke O’Hara, Mirang Park, Laura Butler, Veronica Umeasiegbu, Bradley Mcdaniels, and Malachy L. Bishop. 2019. A qualitative analysis of the employment needs and barriers of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities in rural areas. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling 50: 227–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameri, Mason, and Terri R. Kurtzberg. 2022. The disclosure dilemma: Requesting accommodations for chronic pain in job interviews. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 16: 152–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameri, Mason, Lisa Schur, Meera Adya, F. Scott Bentley, Patrick McKay, and Douglas Kruse. 2018. The disability employment puzzle: A field experiment on employer hiring behavior. ILR Review 71: 329–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, Hilary, and Lisa O’Malley. 2005. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awsumb, Jessica, Michele Schutz, Erik Carter, Ben Schwartzman, Leah Burgess, and Julie Lounds Taylor. 2022. Pursuing paid employment for youth with severe disabilities: Multiple perspectives on pressing challenges. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 47: 22–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ballan, Michelle S., and Molly Freyer. 2020. Occupational deprivation among female survivors of intimate partner violence who have physical disabilities. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 74: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudry, J. S., and L. E. Miller. 2016. Research Design in the Social Sciences: Interdisciplinary Approaches. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bend, Gemma L., and Vincenza Priola. 2018. What About a Career? The Intersection of Gender and Disability. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendick, Marc, Jr. 2018. Employment discrimination against persons with disabilities: Evidence from matched pair testing. International Journal of Diversity in Organisations, Communities and Nations 17: 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, Malachy, and Stuart P. Rumrill. 2021. The employment impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on americans with MS: Preliminary analysis. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 54: 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, Melissa H., Soheil Mahdi, Benjamin Milbourn, Craig Thompson, Axel D’Angelo, Eva Ström, Marita Falkmer, Torbjörn Falkmer, Matthew Lerner, Alycia Halladay, and et al. 2019. Perspectives of key stakeholders on employment of autistic adults across the united states, australia, and sweden. Autism Research 12: 1648–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, Melissa H., Soheil Mahdi, Benjamin Milbourn, Melissa Scott, Alan Gerber, Christopher Esposito, Marita Falkmer, Matthew D. Lerner, Alycia Halladay, Eva Ström, and et al. 2020. Multi-informant international perspectives on the facilitators and barriers to employment for autistic adults. Autism Research 13: 1195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccio, Silvia, Catherine E. Connelly, Ian R. Gellatly, Arif Jetha, and Kathleen A. Martin Ginis. 2020. The participation of people with disabilities in the workplace across the employment cycle: Employer concerns and research evidence. Journal of Business and Psychology 35: 135–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, S., E. Price, and E. Walker. 2018. Fluctuation, invisibility, fatigue—The barriers to maintaining employment with systemic lupus erythematosus: Results of an online survey. Lupus 27: 2284–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosua, Rachelle, and Marianne Gloet. 2021. Access to Flexible Work Arrangements for People with Disabilities: An Australian Study. Hershey: Business Science Reference/IGI Global, pp. 134–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramer, Wichor M., Melissa L. Rethlefsen, Jos Kleijnen, and Oscar H. Franco. 2017. Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: A prospective exploratory study. Systematic Reviews 6: 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bross, Leslie Ann, Melinda Leko, Mary Beth Patry, and Jason C. Travers. 2021. Barriers to competitive integrated employment of young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Education & Training in Autism & Developmental Disabilities 56: 394–408. [Google Scholar]

- Bruyère, Susanne M., Hsiao-Ying Chang, and Matthew C. Saleh. 2020. Preliminary Report Summarizing the Results of Interviews and Focus Groups with Employers, Autistic Individuals, Service Providers, and Higher Education Career Counselors on Perceptions of Barriers and Facilitators for Neurodiverse Individuals in the Job Interview and Customer Interface Processes. K. Lisa Yang and Hock E. Tan Institute on Employment and Disability. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=eric&AN=ED608278&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194 (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Button, Patrick. 2018. Expanding employment discrimination protections for individuals with disabilities: Evidence from california. ILR Review 71: 365–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]