‘Low-Level’ Social Care Needs of Adults in Prison (LOSCIP): A Scoping Review of the UK Literature

Abstract

1. Background

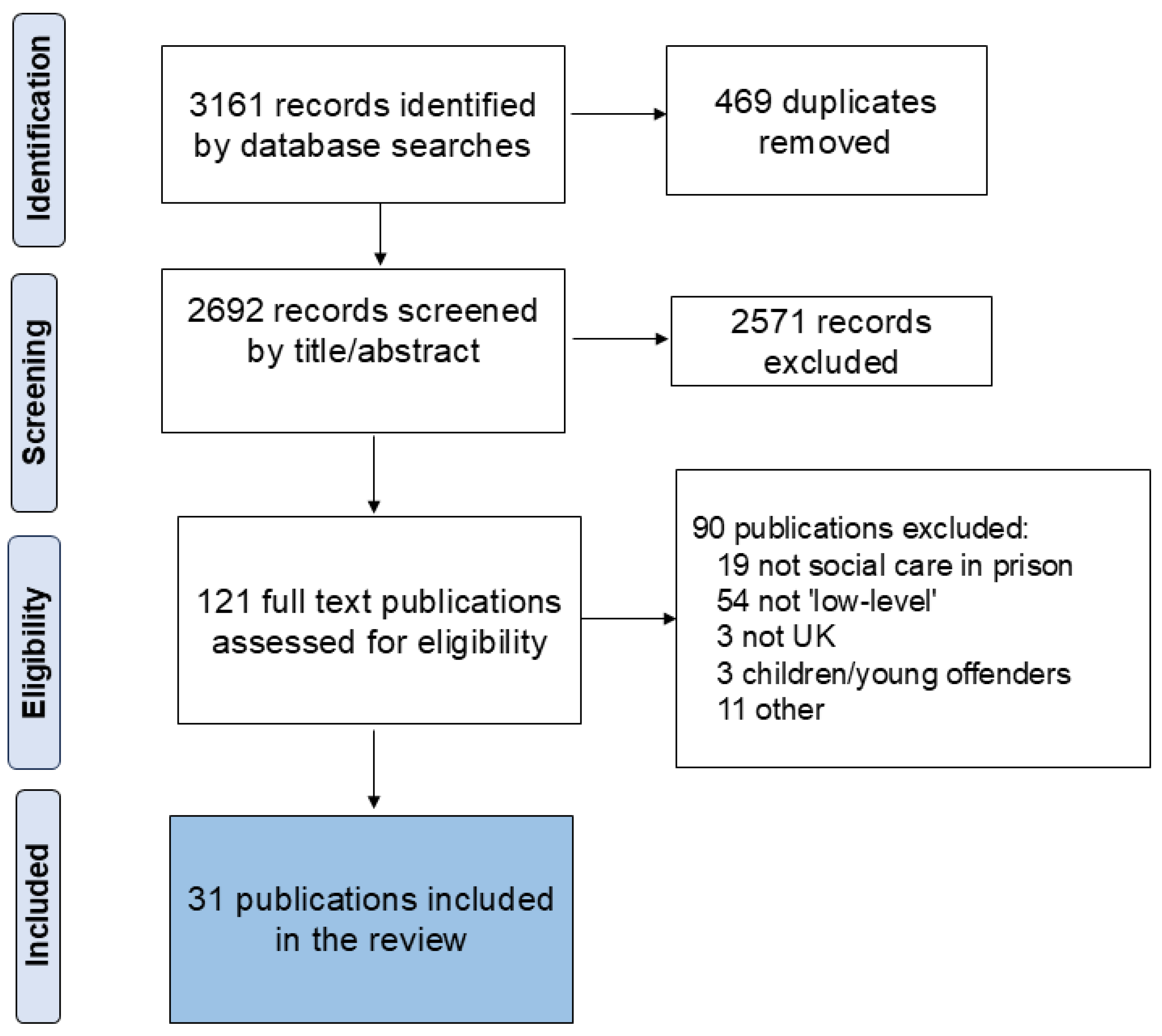

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol

2.2. Scoping Reviews

2.3. Development of Search Strategy

2.4. Screening/Selection Criteria

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Collating, Summarising, and Reporting the Findings

2.7. Stakeholder Consultation

3. Findings

3.1. Conceptualisations of Social Care and ‘Low-Level’ Social Care in Prison

- ‘Low-level’ social care may encompass support for people who have social care needs but who do not meet the threshold for social care packages under current legislation, such as the Care Act (Department of Health 2014) for England and Wales.

- This could include needing support with any of the ten domains of the Care Act 2014:

- ∘

- (nutrition, personal hygiene, toilet needs, being appropriately clothed, making use of home/cell safely, maintaining a habitable home/cell environment, developing and maintaining relationships, accessing and engaging in education or training and work/purposeful activity, making use of necessary services/facilities including technology, and carrying out caring responsibilities for one’s child)

- This could also apply to finance, housing, and personal safety needs and the preservation of human rights and dignity.

- In prison settings, support with ‘low-level’ social care needs may involve help with fetching meals or items from the canteen, getting around the prison, accessing and taking part in out-of-cell activities and social interaction, help with administrative activities including writing letters, and help with remembering appointments.

- Support may cover activities of daily living/prison activities of daily living and coping with the prison regime. It may also relate to receiving visits, advocacy, and befriending.

- Preventing or delaying the development of social care needs, and promotion of independence, are integral to the promotion of wellbeing of people living in prison. Contact with family will be pivotal to this in many cases.

- It is imperative to recognise that referring to these needs as ‘low-level’ does not necessarily mean that they are insignificant to the individual, especially given the Care Act’s high eligibility threshold, which is also open to interpretation.

- ∘

- There are people who have multiple, complex needs but are nevertheless deemed ‘subthreshold’ and therefore will not qualify for formal support packages. In some cases, these needs may be inadequately met, or go unmet, thereby placing people at risk of ‘care poverty’ in which care is a vital, non-material resource necessary for well-being (Zarkou and Brunner 2023; Kröger 2022).

- It should be recognised that some individuals living in prison will be reticent to seek support and may be unaware of their rights or that they have social care needs.

- People involved in providing ‘low-level’ social care/support could include suitably trained and supervised peer supporters, prison officers, education and healthcare staff, voluntary organisations, or family members depending on the nature of the need and with consent from the individual with social care needs.

- It is imperative to ensure that vulnerable people are protected from abuse and neglect, as specified in the Care Act.

3.2. The Nature and Extent of ‘Low-Level’ Social Care Needs in Prison

3.2.1. Types of ‘Low-Level’ Social Care Discussed

3.2.2. Preventing or Delaying Social Care Needs

3.2.3. Promoting Independence

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

4.2. Comparison with Current Literature

4.3. Strengths and Limitations of This Scoping Review

4.4. Implications for Research, Policy and Practice

4.5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alvey, Jan. 2013. Ageing Prisoners in Ireland: Issues for Probation and Social Work. Irish Probation Journal 10: 203–15. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, Hilary, and Lisa O’Malley. 2005. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2019. The Health of Australia’s Prisoners 2018; Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

- Barnes, Deb, Billy Boland, Kathryn Linhart, and Katherine Wilson. 2017. Personalisation and social care assessment—The Care Act 2014. Bjpsych Bulletin 41: 176–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnoux, Magali, and Jane Wood. 2013. The specific needs of foreign national prisoners and the threat to their mental health from being imprisoned in a foreign country. Aggression and Violent Behavior 18: 240–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavidge, Alison. 2020. Integrated Health and Social Care in Prisons: Tests of Change: Workstream Findings and Recommendations. Edinburgh: Social Work Scotland. [Google Scholar]

- Buck, Deborah, Lee D. Mulligan, Charlotte Lennox, Jana Bowden, Matilda Minchin, Lowenna Kemp, Lucy Devine, Joshua Southworth, Falaq Ghafur, Catherine Robinson, and et al. 2024. Developing an initial programme theory for a model of social care in prisons and on release (empowered together): A realist synthesis approach. Medicine, Science and the Law. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinks. 2018. RR3 Special Interest Group on Accommodation: Ensuring the Accommodation Needs of People in Contact with the Criminal Justice System Are Met. Available online: https://www.clinks.org/sites/default/files/2018-09/clinks_rr3_sig-accommodation_v10-ic_0.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Cunha, Olga, Andreia de Castro Rodrigues, Sónia Caridade, Ana Rita Dias, Telma Catarina Almeida, Ana Rita Cruz, and Maria Manuela Peixoto. 2023. The impact of imprisonment on individuals’ mental health and society reintegration: Study protocol. BMC Psychology 11: 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health. 2014. Care Act 2014; London: Department of Health. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/23/contents/enacted (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Department of Health. 2022. People at the Heart of Care: Adult Social Care Reform. Policy Paper. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/people-at-the-heart-of-care-adult-social-care-reform-white-paper/people-at-the-heart-of-care-adult-social-care-reform (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Department of Health and Social Care. 2024. Care and Support Statutory Guidance. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/care-act-statutory-guidance/care-and-support-statutory-guidance (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Durcan, Graham. 2008. From the Inside. Experiences of Prison Mental Health Care. London: Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- Edgemon, Timothy G., and Jody Clay-Warner. 2019. Inmate Mental Health and the Pains of Imprisonment. Society and Mental Health 9: 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enggist, Stefan, Lars Møller, Gauden Galea, and Caroline Udesen. 2014. Prisons and Health. World Health Organization: Regional Office for Europe. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/128603 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion. 2021. Long-Term Care Report—Trends, Challenges and Opportunities in an Ageing Society. Volume II, Country Profiles, Publications Office. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2767/183997 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Farmer, Lord. 2017. The Importance of Strengthening Prisoners’ Family Ties to Prevent Reoffending and Reduce Intergenerational Crime; London: Ministry of Justice.

- Fernandez, Jose-Luis, Juliette Malley, Joanna Marczak, Tom Snell, Raphael Wittenberg, Derek King, and Gerald Wistow. 2020. Unmet Social Care Needs in England. A Scoping Study for Evaluating Support Models for Older People with Low and Moderate Needs. London: London School of Economics: Care Policy and Evaluation Centre. Available online: https://www.lse.ac.uk/cpec/assets/documents/cpec-working-paper-6.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Forsyth, Katrina, Nicola Swinson, Laura Archer-Power, Jane Senior, and Jenny Shaw. 2022. Audit of fidelity of implementation of the older prisoner health and social care assessment and plan (OHSCAP). The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology 33: 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, Katrina, Roger T. Webb, Laura Archer Power, Richard Emsley, Jane Senior, Alistair Burns, David Challis, Adrian Hayes, Rachel Meacock, Elizabeth Walsh, and et al. 2021. The older prisoner health and social care assessment and plan (OHSCAP) versus treatment as usual: A randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health 21: 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Adrian J., Alistair Burns, Pauline Turnbull, and Jenny J. Shaw. 2013. Social and custodial needs of older adults in prison. Age and Ageing 42: 589–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heathcote, Leanne, Alice Dawson, Jane Senior, Jenny Shaw, and Katrina Forsyth. 2024. Service provision for older adults living in prison with dementia/mild cognitive impairment in England and Wales: A national survey. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology 35: 278–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons for Scotland. 2017. Who Cares? The Lived Experience of Older Prisoners in Scotland’s Prisons. Available online: https://prisonsinspectoratescotland.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publication_files/SCT03172875161.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Probation. 2021. A Joint Thematic Inspection of the Criminal Justice Journey for Individuals with Mental Health Needs and Disorders; Manchester: Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Probation.

- Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Probation. 2022. Effective Practice Guide: OMiC; Manchester: Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Probation.

- Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Probation. 2023. Effective Practice Guide. Working with People Subject to Custodial Sentences; Manchester: Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Probation.

- House of Commons Justice Committee. 2020. Ageing Prison Population. Fifth Report of Session 2019–2021; London: House of Commons.

- Howard League for Penal Reform. 2016. Preventing Prison Suicide. Available online: https://howardleague.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Preventing-prison-suicide-report.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Hughes, Sarah E., Olalekan Lee Aiyegbusi, Daniel S. Lasserson, Philip Collis, Samantha Cruz Rivera, Christel McMullan, Grace M. Turner, Jon Glasby, and Melanie Calvert. 2021. Protocol for a scoping review exploring the use of patient-reported outcomes in adult social care. BMJ Open 11: e045206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, Marie. 2016. Visiting time: A tale of two prisons. Probation Journal 63: 347–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, Rose. 2022. Understanding the Lived Experience of Older Men in Prison. Ph.D. thesis, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK. Available online: https://ueaeprints.uea.ac.uk/id/eprint/89960/1/RHutton_thesis_finalversion.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Kröger, Teppo. 2022. Care Poverty: When Older People’s Needs Remain Unmet. Sustainable Development Goals Series. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Caroline, Samantha Treacy, Anna Haggith, Nuwan Darshana Wickramasinghe, Frances Cater, Isla Kuhn, and Tine Van Bortel. 2019. A systematic integrative review of programmes addressing the social care needs of older prisoners. Health Justice 7: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, Susan, Fiona Kumari Campbell, Lynn Kelly, and Fernandes Fernandes. 2018. A New Vision for Social Care in Prison. Dundee: School of Education and Social Work, University of Dundee. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, Helen, Annabel Collins, and Jo Stapleton. 2023. Outreaching to find and engage older people “no-one knows”: A necessary element of work to address social isolation and loneliness. Working with Older People 27: 237–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczak, Joanna, Gerald Wistow, and Jose Luis Fernandez. 2019. Evaluating social care prevention in England: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Long-Term Care 2019: 206–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczak, Joanna, Gerald Wistow, and Jose Luis Fernandez. 2024. Ready, Willing and Able? Local Perspectives on Implementing Prevention in Social Care in England. The British Journal of Social Work 54: 1297–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, Abraham Harold. 1943. A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review 50: 370–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mencap. n.d. Challenging Decisions on Social Care. Available online: https://www.mencap.org.uk/advice-and-support/social-care/challenging-decisions-social-care (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Ministry of Justice. 2013. Government Response to the Justice Committee’s Fifth Report of Session 2013–2014: Older Prisoners (Cm 8739); London: Ministry of Justice.

- Ministry of Justice. 2014. Transforming Rehabilitation: A Summary of Evidence on Reducing Reoffending, 2nd ed.; London: Ministry of Justice.

- Morgan, Theresa A. 2020. Learned Helplessness. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine, 2nd ed. Edited by Marc D. Gellman. Cham: Springer Nature, pp. 1277–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muirhead, Aimee, Michelle Butler, and Gavin Davidson. 2023a. Behind closed doors: An exploration of cell-sharing and its relationship with wellbeing. European Journal of Criminology 20: 335–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muirhead, Aimee, Michelle Butler, and Gavin Davidson. 2023b. Surviving cell-sharing: Resistance, cooperation and collaboration. Punishment & Society 25: 500–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Zachary, Micah D. J. Peters, Cindy Stern, Catalin Tufanaru, Alexa McArthur, and Edoardo Aromataris. 2018. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology 18: 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Offender Management Service. 2016. Adult Social Care; London: National Offender Management Service. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/909378/psi-03-2016-adult-social-care.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- National Probation Service. 2019. Health and Social Care Strategy 2019–2022; London: National Probation Service.

- Netten, Ann. 2011. Overview of Outcome Measurement for Adults Using Social Care Services and Support. London: NIHR School for Social Care Research. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara, Kate, Katrina Forsyth, Jane Senior, Caroline Stevenson, Adrian Hayes, David Challis, and Jenny Shaw. 2015. ‘Social Services will not touch us with a barge pole’: Social care provision for older prisoners. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology 26: 275–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- O’Hara, Kate, Katrina Forsyth, Roger Webb, Jane Senior, Adrian Jonathan Hayes, David Challis, Seena Fazel, and Jenny Shaw. 2016. Links between depressive symptoms and unmet health and social care needs among older prisoners. Age Ageing 45: 158–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Peters, Micah D. J., Casey Marnie, Andrea C. Tricco, Danielle Pollock, Zachary Munn, Lyndsay Alexander, Patricia McInerney, Christina M. Godfrey, and Hanan Khalil. 2020. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis 18: 2119–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, Micah D. J., Christina Godfrey, Patricia McInerney, Hanan Khalil, Palle Larsen, Casey Marnie, Danielle Pollock, Andrea C. Tricco, and Zachary Munn. 2022. Best practice guidance and reporting items for the development of scoping review protocols. JBI Evidence Synthesis 20: 953–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, Danielle, Ellen L. Davies, Micah D. J. Peters, Andrea C. Tricco, Lyndsay Alexander, Patricia McInerney, Christina M. Godfrey, Hanan Khalil, and Zachary Munn. 2021. Undertaking a scoping review: A practical guide for nursing and midwifery students, clinicians, researchers, and academics. Journal of Advanced Nursing 77: 2102–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, Danielle, Micah D.J. Peters, Hanan Khalil, Patricia McInerney, Lyndsay Alexander, Andrea C. Tricco, Catrin Evans, Érica Brandão de Moraes, Christina M. Godfrey, Dawid Pieper, and et al. 2023. Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis 21: 520–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prison Reform Trust. 2014. Human Rights Information Booklet for Prisoners. London: Prison Reform Trust. Available online: https://prisonreformtrust.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/human-rights-bookletdigital.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Prison Reform Trust. 2022. Prison: The Facts. Bromley Briefings Summer 2022. London: Prison Reform Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Prisoners’ Education Trust. 2016. What Is Prison Education for? A Theory of Change Exploring the Value of Learning in Prison. London: Prisoners’ Education Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Psick, Zachary, Jonathan Simon, Rebecca Brown, and Cyrus Ahalt. 2017. Older and incarcerated: Policy implications of aging prison populations. International Journal of Prisoner Health 13: 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilter-Pinner, Harry. 2019. Ethical Care: A Bold Reform Agenda for Adult Social Care. London: Institute for Public Policy Research. [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardelli, Rosemary, Katharina Maier, and Kelly Hannah-Moffat. 2015. Strategic masculinities: Vulnerabilities, risk and the production of prison masculinities. Theor Criminol 19: 491–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, Simone, Leanne Dowse, Danielle Newton, Jane McGillivray, and Eileen Baldry. 2020. Addressing Education, Training, and Employment Supports for Prisoners with Cognitive Disability: Insights from an Australian Programme. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 17: 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, Bethany E. 2013. User Voice and the Prison Council Model: A Summary of Key Findings from an Ethnographic Exploration of Participatory Governance in Three English Prisons. Prison Service Journal 209: 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Government. 2021. Understanding the Social Care Support Needs of Scotland’s Prison Population; Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- Scottish Government. n.d. Social Care. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/policies/social-care/ (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Scottish Parliament. 2018. An Inquiry into the Use of Remand in Scotland; Scotland: Scottish Parliament. Available online: https://bprcdn.parliament.scot/published/J/2018/6/24/An-Inquiry-into-the-Use-of-Remand-in-Scotland/JS052018R07.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Scottish Parliament Justice Committee. 2013. Inquiry into Purposeful Activity in Prisons: Fifth Report 2013 (SP Paper 299); Scotland: Scottish Parliament. Available online: https://archive2021.parliament.scot/S4_JusticeCommittee/Reports/jur-13-05w.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Senior, Jane, Katrina Forsyth, Elizabeth Walsh, Kate O’Hara, Caroline Stevenson, Adrian Hayes, Vicky Short, Roger Webb, David Challis, Seena Fazel, and et al. 2013. Health and social care services for older male adults in prison: The identification of current service provision and piloting of an assessment and care planning model. Health and Social Care Delivery Research 1: 1–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, Glenn, Lucy Mutindi Kaluvu, Jonathan Stokes, Paul Roderick, Adriane Chapman, Ralph Kwame Akyea, Francesco Zaccardi, Miriam Santer, Andrew Farmer, and Hajira Dambha-Miller. 2022. Understanding social care need through primary care big data: A rapid scoping review. BJGP Open 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Lauren Rebecca, Steve Sharman, and Amanda Roberts. 2022. Gambling and Crime: An exploration of gambling availability and culture in an English prison. Criminal Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health 32: 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Social Care Institute for Excellence. n.d. Key Care Act Duties for Assessment and Determination of Eligibility. Available online: https://www.scie.org.uk/assessment-and-eligibility/key-duties/ (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Stewart, Warren. 2018. What Does the Implementation of Peer Care Training in a U.K. Prison Reveal About Prisoner Engagement in Peer Caregiving? Journal of Forensic Nursing 14: 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, Warren, and Rachel Lovely. 2017. Peer social support training in UK prisons. Nursing Standard 32: 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storry, Madeleine. 2022. ‘There’s Lots of Suffering in Here, but Some People Are Suffering More’: Age, Gender and the Pains of Imprisonment. Ph.D. thesis, University of Kent, Canterbury, UK. [Google Scholar]

- The King’s Fund. 2024. Key Facts and Figures About Adult Social Care. Available online: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/audio-video/key-facts-figures-adult-social-care (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Tricco, Andrea C., Erin Lillie, Wasifa Zarin, Kelly K. O’Brien, Heather Colquhoun, Danielle Levac, David Moher, Micah D. J. Peters, Tanya Horsley, Laura Weeks, and et al. 2018. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. The PRISMA-ScR statement. Annals of Internal Medicine 169: 467–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, Andrea C., Erin Lillie, Wasifa Zarin, Kelly K. O’brien, Heather Colquhoun, Monika Kastner, Danielle Levac, Carmen Ng, Jane Pearson Sharpe, Katherine Wilson, and et al. 2016. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology 16: 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, Sue, Claire Hargreaves, Mark Cattermull, Amy Roberts, Tammi Walker, Jennifer Shaw, and David Challis. 2021. The nature and extent of prisoners’ social care needs: Do older prisoners require a different service response? Journal of Social Work 21: 310–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, Sue, Deborah Buck, Amy Roberts, and Claire Hargreaves. 2024. Supporting people with social care needs on release from prison: A scoping review. Journal of Long-term Care, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, Mary, and Marian Peacock. 2017. Palliative Care in UK Prisons: Practical and emotional challenges for custodial staff, healthcare professionals and fellow prisoners. Journal of Correctional Health Care 23: 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, Mary, Marian Peacock, Sheila Payne, Andrew Fletcher, and Katherine Froggatt. 2018. Ageing and dying in the contemporary neoliberal prison system: Exploring the ‘double burden’ for older prisoners. Social Science & Medicine 212: 161–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, Gabriela, Ferdinand Mukumbang, Corey Moore, Tabitha Jones, Susan Woolfenden, Katarina Ostojic, Paul Haber, John Eastwood, James Gillespie, and Carmen Huckel Schneider. 2023. How can we define social care and what are the levels of true integration in integrated care? A narrative review. Journal of Integrated Care 31: 43–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verity, Fiona, Jonathan Richards, Simon Read, and Sarah Wallace. 2022. Towards a contemporary social care ‘prevention narrative’ of principled complexity: An integrative literature review. Health and Social Care in the Community 30: e51–e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, Holly, Amelia Harshfield, Sonila M. Tomini, Pei Li Ng, Katherine Cowan, Jon Sussex, and Naomi J. Fulop. 2019. Innovations in Adult Social Care and Social Work Report. Nuffield Trust. Available online: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-11/adult-social-care-innovations-horizon-scanning-report-final-13112019.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Wavehill Social and Economic Research and Skills for Care. 2019. Prevention in Social Care: Where Are We Now? Leeds: Skills for Care. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, John. 2013. Social care and older prisoners. Journal of Social Work 13: 471–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Kim, Vea Papadopoulou, and Natalie Booth. 2012. Prisoners’ Childhood and Family Backgrounds. Results from the Surveying Prisoner Crime Reduction (SPCR) Longitudinal Cohort Study of Prisoners; London: Ministry of Justice.

- World Health Organization. 2020. Organizational Models of Prison Health. Considerations for Better Governance; Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

- Zarkou, Nafsika, and Richard Brunner. 2023. How Should We Think About “Unmet Need” in Social Care? A Critical Exploratory Literature Review. Scotland: University of Glasgow. [Google Scholar]

| Focus Must include one or more of the following:

|

| Location England, Wales, Scotland, N. Ireland, UK/GB. |

| Population Adults (18+) |

| Setting Male prisons |

| Author, Year | Country | Method | Sample | Refers to Prevention or Delay of Social Care Needs? | Refers to Promoting Independence Regarding Social Care Needs? | Type of ‘Low-Level’ Social Care Needs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forsyth et al. (2021) | England | Mixed methods Questionnaires (Older prisoner Health and Social Care Assessment and Plan; standard health assessment; Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale; CANFOR-S). | 404 older men living in prison | n | n | ‘Low-level’ generally |

| Forsyth et al. (2022) | England | Quantitative. Audit questionnaire. | 497 people living in prison | Y | n | Finances |

| O’Hara et al. (2016) | England | Quantitative. Structured questionnaire | 100 people recently entering prison | n | n | Finances (benefits) |

| Senior et al. (2013) | England and Wales | Mixed methods. National survey; structured and semi-structured interviews. | 127 older men entering prison; 110 staff | n | Y | Finances, benefits, accommodation, dignity, safety to self |

| Barnoux and Wood (2013) | England and Wales | n/a—discussion/opinion piece. | n/a—discussion/opinion piece | n | n | Finances |

| Bavidge (2020) | Scotland | Mixed methods. Evaluation reports from test sites; questionnaires; meetings; workshops; emails. | 24 staff responded to questionnaire | Y | Y | ‘Low-level’ generally |

| Clinks (2018) | England | Qualitative. Consultation and feedback sessions. | Experts by experience (numbers not reported); special interest group members | n | n | Housing; finances |

| Hayes et al. (2013) | England | Mixed methods. Interviews (using CANFOR-S, Lubben Scale (social networks); Quality of Prison Life Assessment; open-ended questions). | 165 people living in prison | n | n | Worry or confusion on reception into custody; safety to self |

| Heathcote et al. (2024) | England and Wales | Quantitative. Survey questionnaire. | 77 heads of prison healthcare; 85 prison governors | n | n | Suitability (size and accessibility) of cells; incontinence aids; “social care aids”; low-level’ generally |

| Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons for Scotland (2017) | Scotland | Mixed methods. Questionnaire survey; interviews; focus groups. | 164 people living in prison; staff views were also considered | n | n | Sleeping; fear of isolation; lack of decent and humane treatment |

| Howard League for Penal Reform (2016) | England | n/a—discussion/opinion piece. | n/a—discussion/opinion piece | Y | n | Finances; safety; dignity |

| Hutton (2022) | England | Qualitative. In-depth, semi-structured interviews. | 17 older men who had experience of prison in later life, either in prison or recently released; 7 prison officers | n | n | Feelings of safety; dignity; privacy; appropriate accommodation |

| Hutton (2016) | England and Wales | Qualitative. Semi-structured interviews; observation; informal and ad hoc interviews with visits staff. | 61 people living in prison and their adult visitors; staff (number not reported) | n | n | Human rights; privacy |

| Levy et al. (2018) | Scotland | Mixed methods. Thematic literature review; qualitative data from interviews, online survey. | Interviews: 3 prison governors, 8 people living in prison; Online survey: 11 Chief Officers of IJB (Integration Joint Boards) | Y | Y | ‘Low-level’ generally |

| Ministry of Justice (2013) | England and Wales | n/a—discussion/opinion piece | n/a—discussion/opinion piece | n | n | Suitable accommodation |

| Muirhead et al. (2023a) | Northern Ireland | Quantitative. Random stratified survey. | 569 men living in prison | Y | n | Perceptions of safety (n terms of shared cells) |

| Muirhead et al. (2023b) | Northern Ireland | Qualitative. In-depth semi-structured interviews. | 37 men living in prison | n | n | Fear for personal safety; invasion of personal space in cell; privacy; dignity |

| Schmidt (2013) | England | Qualitative. Participant observation; interviews; small group discussions. | People living in prison, staff, and User Voice employees (numbers not reported but over 100 h spent in the prisons by the researchers) | n | Y | Feelings of security |

| Scottish Government (2021) | Scotland | Mixed methods. Qualitative interviews; routine data including the Scottish Household Survey, screening results from a Test of Change site, SPS prisoner survey results. | 10 staff (qualitative interviews) | Y | Y | ‘Low-level’ generally; housing; preservation of human rights and dignity |

| Scottish Parliament (2018) | Scotland | n/a—discussion/opinion piece. | n/a—discussion/opinion piece | n | n | Housing benefits/ welfare |

| Smith et al. (2022) | England | Quantitative. Self-completion questionnaire. | 282 people living in prison | n | n | Finances (gambling-related debt) |

| Stewart and Lovely (2017) | England | Qualitative. Unstructured interviews. | 9 people living in prison who had undertaken peer social support training; 2 members of staff | n | n | ‘Low-level’ generally |

| Storry (2022) | England | Qualitative. Non-participant observation; in-depth semi-structured interviews. | 38 older men and women living in prison; 19 staff including governors and wing staff | Y | n | Personal safety; privacy; dignity |

| Tucker et al. (2021) | England | Quantitative. Face-to-face questionnaires including Revolving Doors Prisoner Social Care Screen; modified version of FACE Social Care Screen Assessment. | 482 people living in prison | Y | Y | ‘Low-level’ generally |

| Williams (2013) | England and Wales | n/a—discussion/opinion piece. | n/a—discussion/opinion piece | n | n | Appropriate location of cell; beds; seating |

| Author, Year | Summary/Themes |

|---|---|

| (A) Social care (generally) | |

| Alvey (2013) | Needs in relation to adjustment/coping with prison environment; age-appropriate education programmes or work schemes; maintaining family/social supports; resettlement planning. Achievement of positive personal development. |

| O’Hara et al. (2015) | Much variation between interview respondents (social care and voluntary organisation workers) re: definitions of social care: routine ADLs only (e.g., getting washed or dressed); housing; employment; finances/pensions/benefits. |

| Bavidge (2020) | ‘Support to help people live full lives. Encompasses, daily living tasks, housing support, support to work and take part in leisure activities, relationship and connections to community.’ |

| Lee et al. (2019) | ‘Needing regular help looking after oneself because of illness, disability or old age, … alleviation of social isolation and maintenance of independence…’. Specific to older people in prison: bullying; ‘prison poverty’ (less access to employment or family help); appropriate activities. |

| Levy et al. (2018) | Supporting the ‘daily living of prisoners’; personal care; functional activities of daily living; physical access; provision of adapted cells. Broad and holistic definitions from people living in prison and prison governors, emphasising wellbeing and social dimensions of social care. Connectivity with ‘home’ (prison), family, friends, community; social life. |

| Scottish Government (2021) | Too much focus on physical care needs; not enough attention paid to invisible disabilities. Need to reduce stigma associated with receiving support; improve accommodation; take a holistic approach. ‘Helping people live independently, be active members of the community in which they are part of, and preserve their dignity and human rights.’ Should be more than personal care: focus on ‘wellbeing, the need to support the exercise of agency, citizenship, and opportunities for participation.’ |

| Scottish Parliament (2018) | People on remand in prison: less access to services than convicted people living in prison, specifically in terms of access to/engagement in work/productive activity; courses/programmes; social isolation; access to medical services. |

| Scottish Parliament Justice Committee (2013) | Recommend that definition of purposeful activity (in 2011 Prison Rules (Scotland)) is revised to consider the importance of contact with family. |

| Stewart (2018) | In defining peer support: direct practical help and support but also providing care at social and emotional as well as at the physical level. |

| Walton et al. (2019) | NIHR’s School for Social Care Research definitions: ‘The term “adult social care” refers to provision of personal and practical care and support that people may need because of their age, illness, cognition, disability or other circumstances.’ |

| (B) ‘Low-level’ social care | |

| Bavidge (2020) | Needs which ‘appear low level but are about everyday routine’: taking part in activities; moving around independently; getting to dining room independently; receiving visits; help with remembering appointments/taking medication. Refers to high threshold of eligibility; criteria designed to be applied in the community—heavily weighted towards physical need—meaning those with invisible disabilities/needs may be unable to access support with work, education, or maintaining relationships. |

| Forsyth et al. (2021) | OHSCAP: designed to assess social care needs of older people in prison who do not meet the high threshold for social care packages set by LAs. |

| Heathcote et al. (2024) | No definition but refer to subthreshold needs: ‘it is clear that there is great variation and inconsistency between prisons in their provision of social care services or support for prisoners who do not meet the threshold for social care from the Local Authority’. |

| Levy et al. (2018) | Refer to ‘low level care activities’ in defining peer support, including befriending; fetching meals; help tidy cells; out-of-cell activities; social interaction; administrative activities; buying items from canteen; advocacy. |

| Scottish Government (2021) | Preventative social care: work with people in prison with ‘lower levels of support needs’ by reducing eligibility criteria; could include providing ‘small amounts of support’ such as structured group activities. |

| Stewart and Lovely (2017) | ‘Low-level help and support’ in context of peer support (befriending; fetching meals; help tidy cells.) |

| Storry (2022) | People with significant social care needs who are deemed ineligible for support. |

| Tucker et al. (2021) | Refer to people in prison in England who do not meet Care Act eligibility criteria for social care and support. The Act stipulates that LAs are charged with looking at how people’s general wellbeing could be improved to prevent, delay, or reduce deterioration by (at a minimum) providing advice and information at an individual level. Promotion of wellbeing. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buck, D.; Ali, A.; Butt, N.; Chadwick, H.; Mulligan, L.D.; O’Neill, A.; Robinson, C.; Shaw, J.J.; Shepherd, A.; Southworth, J.; et al. ‘Low-Level’ Social Care Needs of Adults in Prison (LOSCIP): A Scoping Review of the UK Literature. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14020112

Buck D, Ali A, Butt N, Chadwick H, Mulligan LD, O’Neill A, Robinson C, Shaw JJ, Shepherd A, Southworth J, et al. ‘Low-Level’ Social Care Needs of Adults in Prison (LOSCIP): A Scoping Review of the UK Literature. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(2):112. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14020112

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuck, Deborah, Akash Ali, Noor Butt, Helen Chadwick, Lee D. Mulligan, Adam O’Neill, Catherine Robinson, Jenny J. Shaw, Andrew Shepherd, Josh Southworth, and et al. 2025. "‘Low-Level’ Social Care Needs of Adults in Prison (LOSCIP): A Scoping Review of the UK Literature" Social Sciences 14, no. 2: 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14020112

APA StyleBuck, D., Ali, A., Butt, N., Chadwick, H., Mulligan, L. D., O’Neill, A., Robinson, C., Shaw, J. J., Shepherd, A., Southworth, J., Stalker, K., & Forsyth, K. (2025). ‘Low-Level’ Social Care Needs of Adults in Prison (LOSCIP): A Scoping Review of the UK Literature. Social Sciences, 14(2), 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14020112