Abstract

Obstetric violence (OV) is a form of gender-based violence (GBV) that arises from the medicalisation of childbirth and the systematic devaluation of women’s bodies during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period. Recognised as a violation of sexual and reproductive rights, OV reflects historically constructed power relations and highlights the need for public authorities to provide guarantees. In Portugal, OV has historical roots and continues to be an obstacle to the realisation of constitutional principles such as human dignity. Based in an intersectional feminist epistemology and the social constructionist approach, this study was conducted using an exploratory qualitative approach. Ten r7495/2006 acialised Brazilian women were interviewed to examine their experiences of OV during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period in the Portuguese NHS, through the lens of reproductive and sexual rights. The interviews revealed dehumanising and discriminatory treatment, highlighting the lack of respect for these women’s autonomy, dignity, and rights. These experiences of OV during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period affected the participants, leading to trauma and significant negative impacts on their mental, sexual, and reproductive health. This research on OV is crucial to advancing global reproductive justice, as it challenges structural inequalities and places racialised Brazilian women at the heart of the struggle for universal human rights and equality in sexual and reproductive healthcare.

1. Introduction

From the late 19th century onwards, pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period ceased to be predominantly feminine events and became medical practices. This shift was due to the modernisation of approaches and the emergence of gynaecology and obstetrics, which began to medicalise and hospitalise these moments, removing them from women’s control (). Scientific advances in obstetric medicine favoured birth in hospital settings, characterised by the adoption of various technologies and procedures aimed at making it safer. Although hospitalisation for childbirth aims to protect the health of both the pregnant woman and the baby, it often becomes an environment where violence occurs, marked by disrespect for women’s fundamental rights ().

This contributed to a transformation in cultural perceptions of pregnancy, childbirth, and birth. As a result, a model of care was established that often prevents women from taking an active role in childbirth, devalues popular knowledge, and disregards individuals’ needs with respect to scientific knowledge. This exposes women to high rates of interventions that should only be used when necessary (). Consequently, there is a loss of autonomy over women’s bodies and sexuality, negatively impacting their quality of life ().

These harmful practices are commonly referred to as obstetric violence (OV), encompassing various forms, including omission, neglect, physical and psychological violence, sexual abuse, interventions and medications not based on evidence, deprivation of basic needs such as water and food, and other situations that cause suffering to women (). Additionally, intersectional disparities of race, nationality, and gender shape divergent outcomes in maternal health, as well as unequal access to essential healthcare services (; ). As these authors state, current reproductive injustices are contextualised by numerous factors, including the little-recognised history of OV. OV refers to harm inflicted during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period. This violence can be both interpersonal and structural, resulting from the actions of healthcare professionals and broader political and economic arrangements that disproportionately harm this population ().

As a result, pregnant women and those giving birth are vulnerable to situations of violence that materialise through practices present in healthcare institutions. These practices are multifaceted and manifest in power relations, the manipulation of women’s bodies, communication, forms of care, or as violations of rights (). Therefore, intersectionality emerges as an analytical tool, a way of thinking about identity and its relationship to power, which operates as a social practice in institutional and state relations (; ).

Furthermore, (, ) argues that it is essential to recognise that intersectional issues of gender, nationality, and race can help to understand that these women face unique challenges, often leading to an underestimation of the autonomy of racialised Brazilian women and the practices of violence. Investigating how intersectional relations influence social relations in a society marked by diversity is a means to understand and explain the complexity of this context (). Everyone has the right to a respectful pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum period; to control over their body and their biological, sexual, and psychological rights; and to the power to make decisions about what is best for themselves and their child ().

1.1. OV as a Form of Gender-Based Violence (GBV), Institutional Violence, and a Reflection on the Challenges Surrounding Women’s Rights in Portugal

OV is a form of GBV that is closely tied to the medicalisation of childbirth and is shaped by societal attitudes that devalue the female reproductive body during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period (). Women subjected to OV are often in vulnerable conditions, which can amplify the impact and severity of this violence (). This infringes on human, sexual, and reproductive rights, as it constitutes a violation of women’s bodies, dignity, and autonomy at crucial moments in their reproductive lives.

OV is a type of GBV as described in Article 3(d) of the Istanbul Convention, as it defines gender-based violence as that which is directed against women because of their condition, or which otherwise affects them disproportionately (). This is a phenomenon that expresses inequality in the relationship between men and women, occurring in power relations, sexuality, self-identity, and social institutions (). This phenomenon is the result of inequalities expressed through domination, oppression, and cruelty, i.e., actions that result in physical or emotional harm, perpetrated with the abuse of power, based on asymmetries between genders and roles (). Therefore, OV as gender violence affects women because they are one of the genders that give birth, a gender that is subject to medically assisted procreation techniques; in other words, it is violence inherent to the condition of being a woman and a parent.

The term OV was defined by the Venezuelan Law (2007), ‘Organic Law on the Right of Women to a Life Free from Violence’, was the first Latin American legislation to establish and incorporate OV as a form of aggression against women. Since then, the importance of using the term “OV” has symbolised the feminist movement’s struggles to eradicate and punish violent practices during pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum care. This form of violence encompasses all acts performed on a woman’s body without her consent, as well as procedures that are outdated in medicine but still common, especially in care provided by the Portuguese National Health Service (NHS). Examples include episiotomy, the Kristeller manoeuvre (in which the belly is pushed), enemas, the use of synthetic oxytocin, anaesthesia, forceps, fasting from food and water, frequent touch examinations, artificial rupture of the sac, and the imposition of the horizontal position on the woman (; ).

1.1.1. OV in Portugal and Its Obstacles

This practice affects many women around the world. In Portugal, existing studies point to institutionalised violence (; , ; ; ; ; , ). In this case, OV “is a practice in its institutional context which violates women’s basic human rights, disrespect and abuse, with reproductive and sexual rights being neglected” (). The institutional violence that occurs in health centres, hospitals, and maternity wards is called OV, a term used for all varieties of violence and harm that occur during obstetric care. Many professionals involved in healthcare during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period can be responsible for OV ().

The result of these practices is inadequate care for women, contributing significantly to the morbidity and mortality of women and children. It is estimated that 287,000 women die every year as a result of complications related to motherhood (). Some studies show that the feeling of not being informed and not being able to participate in decisions is related to dissatisfaction with the experience of pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period (; ; ; ; ).

In Portugal, OV is still seen as inherent to childbirth. According to the Portuguese Association of Women Lawyers (), it is what is practised against the gender that “… gives birth, the gender that is subjected to medically assisted procreation techniques, in other words it is violence inherent to the condition of a woman, of parenthood” (p. 6). For the Portuguese Association for Women’s Rights in Pregnancy and Childbirth (, ), OV is a form of violence against women in the context of pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum care. It could include refusal of treatment, neglect of women’s needs and pain, verbal humiliation, physical violence, invasive practices, unnecessary use of medication, forced and non-consensual medical interventions, dehumanisation, or rough treatment (, ).

The () explains that the concept of violence, while viewed from different perspectives, must consider its form and origin, the experiences of the victim, and the roles of both the aggressor and society. In the document that covers interpersonal violence, it mentions that the World Health Organisation () emphasises that women, children, and the elderly suffer the most physical, psychological, and sexual abuse. It also emphasises that violence is a phenomenon that is tolerated in parts, i.e., many situations are “accepted” by society as common practice. However, there are still no DGH documents that specifically address OV.

On 9 September 2019, Law 110/2019 () was approved, granting rights to women in the context of sexual and reproductive health as users, which applies to public and private entities and the social sector. This law represents a Second Amendment to Law 15/2014, of 21 March (), signalling a clearer recognition of the problem. It strengthens women’s rights as healthcare users and increases civil medical liability in situations of OV. Notably, it introduces specific rights for women related to their role as parents or potential parents that were previously absent from the legal framework. These rights include, for example, the right of the birthing woman to minimal medical interference during childbirth.

This led to Resolution 181/2021 (), of 28 June, with recommendations to the government to eradicate practices of OV, representing the first legislative instrument in Portugal to explicitly use the term “Obstetric Violence”—a term absent from Law 110/2019 of 9 September. Although women already had support, prior to these aforementioned documents, regarding their rights in the context of obstetric care, the lack of legal recognition of the phenomenon, its conceptualisation, and the normalisation of violence against women have contributed to the invisibility of OV in the courts, which has been absent from the Portuguese jurisprudential debate.

In medicine, this term still meets with resistance, as was evident in 2021, when the () issued an opinion on a proposal for Bill 9i12/XIV/2ª, the result of two surveys launched on social media by the Portuguese Association for Women’s Rights in Pregnancy and Childbirth (APDMGP), stating that the term OV is inappropriate in countries where excellent maternal and child healthcare is provided, as is the case in Portugal. For them, the term does not fit the reality of these countries ().

A year later, this same collegiate body issued an opinion in a letter on 11 September 2022, in which it questioned the editor of the journal The Lancet, who was responsible for publishing an article with a study that placed Portugal as the third-worst country in terms of OV (). The letter also states that, in Portugal and most European countries, OV, whether by action or omission, does not exist as an established practice, unlike the situation of most of the world’s pregnant women, who are exposed to disturbing maternal and perinatal mortality rates, as well as a lack of respect for human rights, particularly in terms of access to health and justice.

1.1.2. Obstetric Racism in Portugal

Unfortunately, in Portugal, this remains a public health problem, which has significantly contributed to the ongoing invisibility of women’s sexual and reproductive rights. Portugal ranks as the third-worst country in Europe for OV (), with some of the highest rates of medicalisation and intervention among European nations (; ). The practice of obstetric racism has also been documented in Portugal (), as well as in other countries in Europe (; ; ; ).

Obstetric racism (OR) manifests at the intersection of OV and medical racism, posing a direct threat to positive outcomes for obstetric patients (). According to the author and creator of the term, OR occurs when a patient’s race influences medical perceptions, treatments, and decisions, compromising care and endangering the patient’s health. Research by the Association for the Health of Black and Racialised Mothers in Portugal () also indicates that more than 20% of Black and racialised women experience OV in Portugal. The same survey reveals that 33.5% of Black and racialised women reported humiliation during pregnancy, 23.4% experienced neglect during childbirth, and 30% underwent non-consensual interventions. These disparities persist regardless of factors such as age, income, or education. Black and racialised women face a higher risk of severe maternal morbidity and potentially fatal complications, many of which are caused or worsened by pregnancy (). It is common for these women to experience daily racialised stigma related to pregnancy, encountering stereotypes that marginalise their motherhood and result in negative consequences for both them and their children ().

To reinforce this theme, the results of studies with racialised women in Portugal reveal that these debates are mostly centred on White European women who have the same profile as their most prevalent audience (, ). The findings of two online surveys on women’s experiences of childbirth illustrate a highly interventionist context, where women often feel objectified, and their preferences and demands are frequently disregarded (, ).

1.1.3. Abandonment, Refusal of Care, and New State Measures

In addition to the neglect of women’s care during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period, Portugal has been grappling with challenges such as the closure of maternity hospitals, as well as birthing blocks and obstetric and gynaecological emergencies. This type of embarrassment is yet another type of OV and/or institutional violence, according to () classification: “abandonment and refusal of care”, one of the situations that, according to the WHO, amounts to a violation of women’s fundamental human rights. All women have the right to the highest attainable standard of health, including the right to dignified and respectful care throughout pregnancy and childbirth, as well as the right to be free from violence and discrimination (). If a pregnant woman requires emergency care, a helpline for pregnant women in the NHS 24 was established at the end of 2024. However, this compromises the clinical safety of these women, in addition to limiting their freedom to choose the hospital where they wish to receive care, which violates the current law on free access and circulation within the NHS: Despacho nº 7495/2006 (), (2nd series), dated 4 April, reinforced by the Constitution of the Portuguese Republic (CRP, Article 64).

Unfortunately, Portugal is also implementing new policies that increase barriers to healthcare access for the immigrant population. In December 2024, right-wing extremist parties, which have recently propagated hate speech against immigrants, approved Draft Law No. 364/XVI/1st () in the Assembly of the Republic, which restricts access to the NHS for non-resident citizens. The justification for this legislation is “health tourism”, a practice whereby foreign nationals come to Portugal solely to benefit from free healthcare (). According to one of these parties, although this practice may seem beneficial at first glance, it has serious consequences for the structure and capacity of the NHS.

Data from the General Inspectorate of Health Activities () indicate that, between 2021 and September 2024, more than 140,000 non-resident citizens sought care from NHS emergency services without international insurance or agreements to cover the costs. This number has increased by more than 26% in the last two years, rising from approximately 36,000 cases in 2022 to over 45,000 in 2024. However, this situation is not the result of the current regulations, such as the Basic Health Laws 2 and 21 () or the NHS Statute (), which guarantee access to the NHS for immigrants in irregular situations. One of the main issues is the difficulty of scheduling appointments at the Agency for Integration, Migration, and Asylum (). In 2024, there were at least 400,000 pending cases at the AIMA, harming many families with limited access to essential services like healthcare and education (). This crisis reflects the AIMA’s disregard for immigrants, contributing to their growing vulnerability.

These issues directly affect maternal care. Immigrant women, struggling to regularise their status and requiring prenatal care, often face discrimination and violence. Their irregular situation is often disparagingly labelled as “birth tourism” by right-wing extremist parties, which claim that many public hospitals are receiving large numbers of pregnant women without prior registration in the NHS ().

Women find themselves in a sensitive and highly vulnerable moment, requiring appropriate, specialised care and well-trained professionals for this phase. This is due not only to the pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum care but also to the immigration process, which involves loneliness, lack of support networks, cultural barriers, and difficulties accessing information. For these women, these challenges are amplified, making the implementation of appropriate public policies even more urgent. The quality of maternal healthcare is an essential indicator of a country’s development. Therefore, it is urgent to combat discriminatory policies that hinder women’s access to medical care and their sexual and reproductive rights, as well as dismantling the stereotypes that fuel discrimination against marginalised women during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period. Specific and reinforced measures are needed to ensure that all women, regardless of their situation, have access to high-quality maternal healthcare, including family planning services, prenatal care, safe childbirth, and postpartum follow-up ().

Taking the above into consideration, beyond the normative and abstract levels of international legislation and regulations, it is essential to analyse how Portugal has approached reproductive rights and new reproductive technologies in practice, with a focus on protecting these rights (). Public policies, the ultimate expression of the executive branch’s actions, play a key role in consolidating equality in its territory through its institutions, norms, and models that guide its decisions, elaborations, implementations, evaluations, and verification of results. In terms of policies to meet the demands of sexual and reproductive health in Portugal, the internal pressure is largely due to the important women’s movements, which, as () states, have been fundamental in demanding and driving change in all of these areas.

1.2. Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH): A Fundamental Human Right and the State’s Responsibility to Uphold Human Dignity

OV in Portugal has historical roots and is still present in society, representing an obstacle to the fulfilment of constitutional principles, especially that of human dignity. According to the (), this form of violence occurs when health professionals take ownership of women’s bodies and reproductive processes, imposing dehumanised treatment. In practice, it manifests itself through excessive medication or the pathologisation of natural processes, limiting the ability of the pregnant, parturient, or puerperal woman to make autonomous decisions about their body and sexuality. This type of aggression, whether moral or verbal, has a negative impact on women’s quality of life, profoundly affecting their physical, psychological, and emotional integrity ().

All women have the right to the highest attainable standard of health, including the right to dignified and respectful care throughout pregnancy and childbirth, as well as the right to be free from violence and discrimination. Abuse, mistreatment, neglect and disrespect during childbirth amount to a violation of women’s fundamental human rights, as described in internationally adopted human rights standards and principles. Pregnant women have the right to be equal in dignity, to be free to seek, receive and impart information, not to suffer discrimination and to enjoy the highest standard of physical and mental health, including sexual and reproductive health.()

“Dehumanised treatment”, a core aspect of OV, is understood from the perspective of the demeaning of women’s dignity, both morally and physically. Violence against women requires analysis within the context of gender, which encompasses the social, political, and cultural construction of masculinities and femininities. Historically, the differences between male and female created a disparity of opportunities and roles in the family and social spheres. Over time, feminist movements have been essential in winning equal rights, allowing women to occupy new social spaces. In this way, women’s roles ceased to be tied exclusively to the home, reaching new spheres of activity.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted and proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly (Resolution 217 A III) on 10 December 1948 (), was fundamental, as it marked the beginning of a global system for the protection of human rights. It states that all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights, and that they may invoke the rights and freedoms proclaimed without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth, or other status. The Declaration affirms that everyone is equal before the law and entitled, without distinction, to the same legal protections. It also guarantees protection against any discrimination that violates the principles of the Declaration, as well as against any incitement to discrimination.

The Declaration guarantees a series of fundamental rights, including the right to health and well-being for oneself and one’s family. The right to health is a fundamental social right, collectively owned, and has a positive character, as it requires state intervention for its full realisation. As it is a collective right, the Constitution guarantees it to everyone, without distinction. However, when a universal right is denied to certain social groups, this is a clear violation of what is established in the Constitution, becoming a violation of the dignity of the human person.

With this in mind, it is important to emphasise that sexual and reproductive rights are fundamental components of human rights. These rights contribute to equality, dignity, and freedom, as well as to integrity, tolerance, and acceptance. They are essential for fostering a positive and healthy experience of sexuality (). In this case, OV consists of the violation of women’s rights during maternal healthcare (). This includes all verbal or physical aggression, or even negligent acts, omissions, and delays in the provision of obstetric services, i.e., inadequate assistance to pregnant and parturient women during the performance of any related procedure.

The Organic Law on Women’s Right to a Life Free from Violence treats OV as a political, public, and social problem (). This law uses the term “obstetric violence” in a specific way, becoming an international regulatory model for the conceptualisation of violence against women. It is understood as a violation of human rights and a manifestation of historically constructed power relations, as well as a demand for the guarantee of rights by public authorities ().

In Portugal, OV is a routine practice during pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum experiences among women, causing serious consequences such as physical, psychological, and social problems, making it a public health issue (, ; ). In this context, the legal instruments produced internationally and nationally aim to ensure that women’s reproductive and fundamental rights are guaranteed (). However, OV is far from being eliminated, mainly due to the silence of victims, their lack of knowledge of their rights, the omission of state assistance, and other deficiencies that are not prioritised ().

All of these factors are magnified when it comes to immigration. Depending on the conditions in which it occurs, it can increase or decrease people’s vulnerability, posing a threat to health. Factors such as cultural differences, gender stereotypes, social traditions, language barriers, and communication patterns intensify these vulnerabilities, since they vary between cultures and often affect the reception of migrants in destination countries (). This situation is exacerbated when immigrants face ongoing social exclusion, which creates barriers to accessing health services (; ). Furthermore, even when they do manage to access health services, they often face stereotypes and are treated unequally (; ; ).

Although health is a fundamental aspect to consider in the immigration process, many studies on population displacement focus only on labour and economic issues, neglecting health aspects and the complexity of immigrants’ lives (; ; ). When it comes to immigrant women and sexual/reproductive health issues, the picture becomes even more worrying. This is because, in addition to the impact of immigrant status, gender stereotypes and cultural morality influence the ways these patients are cared for in health services. Research indicates that immigrant women have higher rates of maternal morbidity and mortality, lower adherence to preventive guidelines, and lower use of health services compared to Portuguese women (; ).

Due to Brazil’s historical context, the intersection with gender and nationality categories also raises issues related to race. These intersect to create a landscape of inequality, confirming the existence of symbolic violence produced by a type of discourse around the notions of race, sexuality, aesthetics, and morality that is perpetuated as a form of racism in the way of looking at and disqualifying the racialised body (; ). These discourses are internalised through a process of naturalisation, reinforcing racial hierarchies that have become accepted as defining historical characteristics of Portuguese society (). Thus, unequal power relations intersected by structural racism make it possible to attempt to regulate bodies, substantially affecting racialised women as a means of adapting their sexual and reproductive functions.

In this regard, () emphasise that, when analysing situations of inequality, it is essential to consider the intersections of various power relations, such as racism, patriarchy, sexism, machismo, heteronormativity, and other forms of oppression. The dynamics of power associated with intersecting identities—such as race, nationality, and gender—shape social interactions and influence individual experiences of discrimination. In this context, (), when addressing intersectionality, highlights the necessity for human rights institutions to take responsibility for addressing the causes and consequences of racial discrimination.

Although the aim of the social and health policies proposed based on human rights is to redress social injustices and inequalities in relation to women, especially racialised women, it is known that the state is racial and class-based, i.e., structurally determined by racial classification and formed by social hierarchies constituted by race and gender relations (). The state proposes policies with the aim of reducing social inequalities, but it is these same inequalities that sustain it through structural racism that ratifies social hierarchies. Racialised women experience a higher incidence of OV, as they receive less information about their pregnancy, childbirth, and prenatal care. There is a clear disparity in the quality of care provided by health services based on race and ethnicity, and racialised women also face higher rates of unplanned pregnancies (; ). Therefore, as () state, intersectionality is multifaceted.

It is therefore essential to think about the interconnections of human rights reflected in all of the elements that make up the rights to SRH, as well as the policies and funding needed to guarantee universal access to it. SRH concepts are relatively recent and have undergone significant transformations over time, influenced by various socio-cultural, political, and medical–scientific factors. These changes have made it possible to recognise that everyone has the right to experience their sexuality in a free, safe, and informed way ().

The Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development, Cairo, 1948, () explains that the concept of SRH implies that people can have a satisfying and safe sex life and decide whether, when, and how often to have children. This last condition presupposes the right of every individual to be informed and to have access to family planning methods of their choice that are safe, effective, and acceptable, as well as to adequate health services that enable women to have a safe pregnancy and childbirth, offering couples the best opportunities to have a safe pregnancy and childbirth and to have healthy children. It also encompasses the right to sexual health, understood as an enhancer of life and interpersonal relationships.

In 2019, it was estimated that 6.6% of women of reproductive age in Portugal had unmet contraceptive needs. According to the charter of sexual and reproductive rights of the (), everyone has the right to receive information, free from discrimination, to make free and informed decisions about their health. However, according to the (), there are still difficulties in accessing this information faced by the Portuguese population itself, suggesting that if this is the case for the natives, it will be worse for the immigrant population.

In recent years, the non-national population in Portugal has been steadily increasing. According to the AIMA Migration and Asylum Report (), Brazilian nationals represent the largest group, accounting for 35.3% of the non-national population. Studies carried out in Portugal have highlighted a high prevalence of unplanned pregnancies among immigrants (; ). Additionally, data from the DGH in 2022 revealed that 28.9% of voluntary terminations of pregnancy that year involved non-national women, with Brazilian women being one of the most represented in this group. These data suggest that many immigrant women in Portugal may have unmet family planning needs.

Based on this information, we seek to reflect that the issue of SRH is currently one of the main public health concerns, because of the practice of OV among this population. When certain social groups—such as sexual minorities, including racialised Brazilian women—are denied their rights to sexual and reproductive health, they are suffering a violation of their sexual and reproductive rights, which consequently implies a clear affront to the dignity of this population. Thus, by denying these women the right to health, unjustifiable restrictions are imposed on their well-being and quality of life—both essential elements of the concept of health. As a result, these women live in conditions of inequality and face constant violations of their dignity.

In this case, all of these factors should be guaranteed by the state as a way of promoting SRH as a fundamental principle of human dignity, but they are harmed because the way in which health institutions and practices are organised in society reproduces this context, in most cases offering fragmented care with low resolution and shrouded in discrimination and prejudice (). In the case of racialised Brazilian women, this fact materialises in the daily need to face the limitations imposed by social invisibility, prejudice, and discrimination, which are present in different contexts of their lives, including the NHS () It is therefore important to seek to analyse the fundamental social right to health from its constitutional perspective, with an emphasis on promoting SRH for this population, considering this right as one of the factors capable of promoting the guarantee of human dignity.

1.3. The Current Research

As the most significant population in Portugal, racialised Brazilian women also make a notable contribution to national birth rates. However, research into their experiences is still underdeveloped and unsatisfactory. This exploratory qualitative study aims to fill this gap. The aim is to explore a specific unit in depth to gain insights that would not have been achievable through other approaches ().

Grounded in an intersectional feminist epistemology and the social constructionist approach, this research examines the experiences of OV during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period among racialised Brazilian women in the Portuguese NHS, through the lens of reproductive and sexual rights. As a form of GBV, OV raises questions about the violation of human rights and its consequences. This issue has gained increasing attention in the health sector worldwide, as it contributes to severe physical, psychological, and social problems. This study aims to address OV as both a public health problem and a human rights issue, and to analyse its impact and consequences on affected racialised Brazilian women in the NHS. Therefore, the following research question was developed to guide the entire study: How do racialised Brazilian women experience and perceive OV within the healthcare context in Portugal?

It is important to emphasise that this methodology is highly individualised and focuses on a specific segment of the population. Therefore, the findings cannot be generalised to the broader population.

2. Materials and Methods

This study used an exploratory qualitative approach, with semi-structured individual interviews as the data collection tool. The aim of this case study was to explore a specific unit in depth to gain insights that would not have been achievable through other approaches (), as well as to explore and gain a comprehensive understanding of the experiences and realities of the interviewees, collecting fundamental data for a detailed analysis of their beliefs, attitudes, values, and motivations concerning specific social actors and contexts. This approach was selected because it provides a more thorough understanding of the experiences, attitudes, interactions, and behaviours of racialised Brazilian women in maternal health settings, thus more effectively meeting the purposes of this study.

A structured instrument validation framework was followed to ensure that the instrument accurately reflected its intended purpose, drawing on the Validation for Qualitative Research Instruments (Vali-Quali) methodology developed by (). This is a qualitative data validation instrument applied to semi-structured interview guides. An initial scientific review of the subject matter was conducted to establish content validity. This proposal encompassed two key dimensions: content and semantics. To validate the content of the instrument, a comprehensive scientific review of the topic was undertaken, with the aim of evaluating the extent to which the instrument accurately represented the specific content domain being measured. The validation process was structured into six integrated phases: drafting the initial script, review by experts, analysis of results, conducting a pre-test, refining and validating the script, and finalising a theoretical–empirical version of the instrument.

In this context, the validity of the instrument was assessed based on four core attributes: alignment with research objectives, adherence to theoretical constructs, clarity of language, and qualitative expectations. Experts were invited to review the semi-structured interview questions and provide feedback on the following aspects: (a) clarity of content: ensuring that the questions are formulated clearly and precisely, making them easily understandable for participants with diverse experiences; (b) clarity of wording: confirming that the language and terminology used are appropriate for the intended audience; (c) logical organisation: evaluating whether the content of each question is aligned with its assigned category, and whether the questions are presented in a logical and coherent order; (d) relevance of information: assessing whether the questions are pertinent and capable of providing the necessary data to meet the research objectives; and (e) appropriate question count: reviewing the number of questions to ensure that the interview is concise enough to maintain participant engagement without compromising the breadth of information collected.

Additionally, the reviewers were given space to offer recommendations, suggest alternative wording for unclear or inappropriate questions, and propose other refinements. After thorough analysis, feedback, and pre-testing, the instrument was deemed valid, as it effectively addressed all elements related to the conceptual framework of the construct. The development of the items was grounded in a clear conceptual definition of the variable being measured, ensuring that the semantic meaning was accurately captured. The items were assessed as relevant, aligned with the construct, and representative of the dimensions outlined in the semantic definition.

Quantifying the degree of content validity using appropriate indicators was essential to ensure the robustness of the instrument. This process also emphasised transparency, refinement of the tool, and methodological rigor, reflecting the maturity and reliability of the research. As a result, the validation reinforced the trustworthiness of the qualitative research approach.

These processes were reviewed by two reviewers with expertise in qualitative research: a full professor with a PhD in Social Psychology and an academic career since 1988, and an assistant professor with a PhD in Social Psychology and an academic career since 2011. The interview consisted of two parts—the first collecting sociodemographic data, and the second made up of seven sections: (1) migratory journey (e.g., What changes have taken place since immigrating?), exploring questions of identity, family, personal, social, and cultural aspects; (2) being a pregnant migrant in Portugal (e.g., What has it meant for you to be a pregnant woman in Portugal?); (3) pregnancy (e.g., Could you tell me about your pregnancy, especially your prenatal care? What was it like for you?); (4) childbirth (e.g., Did you feel that your fundamental rights were guaranteed during labour?); (5) postpartum (e.g., Could you tell me a little about what changed in your life before and after giving birth?); (6) OV (e.g., Do you think you have been the target of obstetric violence? If so, what elements facilitate these situations?); and (7) final considerations (e.g., How satisfied are you with maternal care (perinatal, childbirth, puerperium), taking the conditions of being a racialised Brazilian woman in Portugal into account?)

This study was then approved by the ethics committee (anonymised for peer review) (Ref.ª 2023-09-07c), as it adhered to all of the ethical principles of research, including informed consent and the protection of personal data. The voluntary nature of participation, anonymity, data processing and storage, and confidentiality were guaranteed.

The form of recruitment to take part in this study was the convenience sampling method, with ads being shared on social media platforms (e.g., Instagram and Facebook). In order to take part, the respondents had to meet the following criteria: be Brazilian women living in Portugal, be aged 18 or over, identify themselves as racialised, have given birth in the country in the last three years, and realise that they had experienced OV in the Portuguese NHS. Another way of recruiting participants was also used: the snowball sampling technique, in which the participants were encouraged to refer other women who met the inclusion criteria, enabling wider access to potential interviewees. As a result, there was no control over variables such as the age, marital status, or sexual orientation of the participants.

The interviews were scheduled through direct contact, telephone, or email after obtaining the informed consent of those involved. Before beginning each interview, the objectives were explained, and the participants were assured of their anonymity and confidentiality. Explicit permission was obtained to record and transcribe the interviews. All interviews were conducted online via the ZOOM platform to suit the convenience of the participants. Participation was completely voluntary, and data collection took place between February and April 2024, with each interview lasting an average of 60 minutes.

The principle of saturation was achieved during the twelfth interview, at which point the data collection process was considered complete, and the sample was finalised due to reaching theoretical saturation. This indicates that the theoretical sampling was established, data were gathered, and a systematic analysis of the information was conducted (). According to the authors, no new insights or information surfaced, and all of the concepts central to the theory were thoroughly developed. The relationships and connections between the concepts that underpin the theory were confirmed, leaving no need for further data collection (). Every aspect of the theory was fully substantiated, eliminating any hypothetical elements. This demonstrates that the sample of twelve participants was sufficient, as the data collected were of high quality, and no new categories emerged. The boundaries of the concepts were clearly defined, and the related concepts were identified and clarified, ensuring that the understanding of the studied phenomenon remained consistent and complete.

This study involved 12 racialised Brazilian women aged between 31 and 44 (M = 35.52; SD = 3.94). They were all cisgender women, eleven of whom identified as heterosexual and one as bisexual. They had between one and three children (M = 1.4; SD = 0.67). In terms of education, eight participants had a bachelor’s degree, three had a master’s degree, and one had a doctorate. They had lived in Portugal for between two and seven years (M = 3.5; SD = 1.61). All of the participants reported having suffered OV in the Portuguese NHS (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants.

Twelve women took part in the interview because it was realised that the principle of saturation had been reached, as no new information or themes emerged, and the data collection was considered complete. Theoretical saturation was reached, meaning that the concepts and their relationships had been fully developed and verified, and no new data were needed to advance the theory. With all of the conceptual boundaries well defined and the links between them clearly established, a sample size of ten participants was considered sufficient to capture the quality and depth of the phenomenon under study.

The interviews were analysed using thematic analysis (TA), as outlined by (, ). The case study sought to delve deeper into a specific unit, providing a more complete understanding than would be possible with other methods (). This qualitative approach is a valuable tool for identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns in the data, offering a detailed interpretation of the narratives (, , ).

The analysis went through Braun and Clarke’s six stages (, , ). First, there was familiarisation with the data, with careful readings of the transcripts to identify codes and gain an in-depth view of each participant. In the second stage, initial codes were generated from the transcribed narratives, organising the main characteristics into themes and sub-themes. In the third stage, “searching for themes”, a central theme was identified that encompassed the relevant data and gave rise to thematic insights. The fourth stage involved “reviewing the themes”, refining them to ensure that the coded data were consistent with each theme, resulting in a thematic map. The fifth stage, “defining and naming themes”, consisted of clearly defining each theme. Finally, in the sixth stage, “producing the report”, we organised the findings into a coherent narrative ().

3. Results

The results presented in this study confirm that unnecessary obstetric interventions are frequently carried out in various hospitals and health centres in Portugal, alongside physical, sexual, psychological, and institutional violence, lack of autonomy and rights, unequal power relationships, discrimination, barriers, and stereotyping (; , ; ; ; ; , ). Combating the countless violent and traumatic acts that affect the majority of women is a driving force behind this research, and an aggravating factor is the issue of immigration—a situation for which the scientific literature is still scarce and women’s issues more invisible, particularly racialised Brazilian women living in Portugal, who are faced with a lack of respect for their autonomy, dignity, and rights during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period.

Unfortunately, these women’s experiences during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period were not positive. OV is a term that is gaining familiarity among women who seek access to information from the moment that they choose to reproduce. As a result, the women in this study realised that OV was present at all stages (pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum) according to a set of definitions that describe various practices of invisibility, subjectivation, and polyphony. Knowing women’s perceptions of this reality and exploring their views and opinions, as well as the levels of information that women have about OV, is a first step towards change so that it is not seen as “acceptable” in the future.

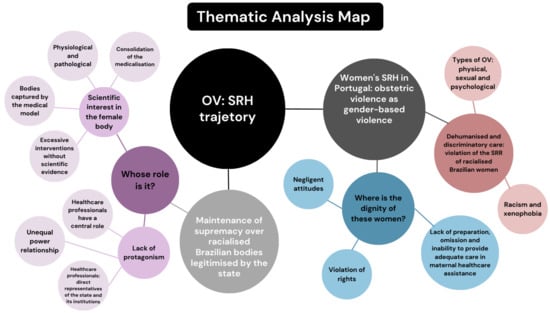

Based on the theoretical support, in this case study, a data collection instrument was developed that yielded significant results, thus providing answers to the questions that will be presented (). In accordance with this reality, the TA allowed us to identify a set of themes and sub-themes in the discourses of the 12 interviewees, which we entitled and set out as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Thematic analysis map.

3.1. Maintenance of Supremacy over Racialised Brazilian Bodies Legitimised by the State

Gender-based violence (physical, sexual, and psychological), in this case against racialised Brazilian women, is manifested through historically and culturally unequal power relations between men and women. The findings of this study reveal how this power relationship is exercised in the Portuguese NHS. The health professionals who make up the maternal healthcare context—direct representatives of the state and its institutions—play a central and determining role during this phase of life, showing that they are often the only protagonists. This power relationship turns the process of monitoring pregnancy and childbirth into something that is simply physiological and pathological, taking away women’s protagonism and enabling the exercise of multiple forms of OV.

What was found was that racialised Brazilian women became victims of OV, characterised by inertia, passivity, and silence—in other words, by annulment. This has had physical, sexual, psychological, and social consequences. These women see their plans, dreams, and expectations for each phase of this event captured by the medical model. This makes them believe that they are incapable of facing this phase of their lives with health and joy, and they start handing over the work to others, reinforcing a false idea that this is an honourable and socially acceptable way out.

Whose Role Is It?

The events that take place through these women’s bodies during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period demand that the centrality and focus be on them. This requires a direct and effective dialogue between health professionals, where questions, doubts, and plans regarding their needs during these phases can be developed. However, during contact with the NHS, the results were the opposite of what might have been expected. One form of violence highlighted by the participants was communication with the professionals present during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period, marked by a lack of information before procedures being carried out, verbal aggression, and a rude tone of voice, revealing indifference and inattention, as the discourse shows:

“This birth plan thing, it was more something I did on my own with the help of the internet because my doctor, she didn’t encourage much”.(P1)

“Everything was summarily disregarded; it was as if you were exaggerating”.(P6)

“She came in telling me she was going to do the test. I said no and she still did it. She was violent”.(P10)

It is clear from the participants’ discourse that the principle of autonomy and self-determination—that the individual can decide on their personal choices and should be treated with respect for their ability to make decisions—was ignored by health professionals. Women should have the right to decide on matters relating to their bodies and their lives. Any medical procedure should be authorised by the patient.

As a result, scientific interest in understanding the female body is growing, mainly due to the fundamental component of the consolidation of the medicalisation of women. The accounts confirm the absence of the woman, who was previously seen as the central element, dominant over her body and empowered by others, but now being excluded from this process because she has been judged as lacking sufficient scientific knowledge to master the practice.

“And then they gave me oxytocin, they gave me a pill now, intravaginally”.(P6)

“I heard the doctor telling the nurses at various times that I was weak”.(P7)

“A person full of pain, trapped in wires, full of drugs. I couldn’t give birth on my own, pushing without contractions, in a position I didn’t want…”(P10)

“The doctor can’t do everything, but in the public sphere we are more susceptible to medical power”.(P10)

These statements demonstrate how racialised Brazilian women are also treated within the Portuguese NHS, and that this is not an exclusive phenomenon for national women. The idea that these women need interventions, orders, and impositions promotes a clear exclusion of these women during an event that takes place through their bodies, which are captured so that they no longer belong to the sphere of the feminine but are understood as a medical practice.

Aware of their situation, these women understand the violations that they have suffered and suffer from the silencing of their desires and expectations. Throughout the event, these women knew that they were capable of being protagonists from pregnancy to postpartum because, as inhabitants of these bodies, they know and recognise them as the owners of this system that makes them who they are. The event is theirs, in them, and for them. This is why they announce their ability to take the lead, as can be seen below:

“(…) to be received with affection, to be the protagonist of my labour, to have control, right? Control but being able to decide what was best for us. To really be the protagonist”.(P6)

Unfortunately, the lack of protagonism of racialised Brazilian women in the NHS, from pregnancy to the postpartum period, has promoted OV, which influences the processes of this event, generating trauma and suffering. Annulling this protagonism is a way of infringing on sexual and reproductive rights, as can be seen in the testimonies. This weakens women’s autonomy and their leading role in the decision-making process. It also leads to poor quality and humanisation of maternal care.

3.2. Women’s SRH in Portugal: OV as GBV

OV is an integral part of a society that violates women because of their gender identity and female status. It is the result of male domination that gives rise to machismo, both institutional and individual, and which affects women’s various relationships with their bodies, their position in society, and their dignity. SRH is a state of physical, mental, and social well-being, but unfortunately, in the findings of this study, gender-based violence based on inhumane treatment and discrimination was unanimous among the interviewees, revealing violations in SRH care that ended up injuring the dignity of these women.

3.2.1. Dehumanised and Discriminatory Care: Violation of the Sexual and Reproductive Rights of Racialised Brazilian Women

Dehumanised care starts with disrespect, which was found to be common in this study. The OV suffered by these women proves a constant violation of the dignity of the human person. These women were victims of disrespect and abuse—inhuman acts that end up generating physical, sexual, and psychological consequences. This hurts their integrity, as a result of the state’s neglect of women’s health. As can be seen, these women have undergone procedures that affected their physical bodies.

“(…) Take touch. So I said: no, I don’t want you to touch me anymore. But you have to”.(P4)

“The doctor came to do a touch test and I said: no, no, I’m in pain, you’re mistreating me”.(P5)

“(…) they did the episiotomy, at no point did they ask me if I authorised it or not… I had my scar, the three cuts I had suffered (…)”.(P6)

“He said: I’m sorry, but I’m going to have to do one more nasty thing, I’m going to have to remove your placenta. He stuck his hand inside my vagina, inside my uterus, to pull out my placenta. And in the process, I said: it’s hurting, it’s hurting and he said: but it has to be like this”.(P9)

The results also reveal sexual violence generated by the constraints imposed by the health professionals who accompanied these women during maternal healthcare. Touch examinations, episiotomies, and interventions could cause injuries and trauma. Physical injuries end up affecting these women’s sex lives. This situation exposes the deep fragility of these women.

“I was feeling my body locking up, you know? Locking up because it’s a strange person touching me (…)”.(P4)

“(…) to this day I feel the consequences of my sex life not returning to normal, because I no longer have the same lubrication”.(P6)

This violation, characterised by frequent touching, episiotomy, and exposure of the body, among other situations, is sexual OV. The data reveal that these women experienced such violence, which is defined as any action imposed on a woman that violates her intimacy and undermines her sense of sexual and reproductive integrity, regardless of whether it directly affects/involves her sexual organs or other intimate parts of her body.

In addition, these women also reported experiencing the impacts of this violence, including psychological damage, which can be long-lasting. The psychological aspect of the abuse is explained in cases of lies, humiliation, rudeness, blackmail, offences, omission of information, language that is not very accessible, disrespect, or disregard for their cultural standards.

“Because the whole time the guy was threatening me with a caesarean section (…)”.(P4)

“I started screaming, a nurse came to restrain me and held my arm”.(P5)

“If you can’t handle a touch, do you think you can handle a normal birth?”.(P8)

“She bombarded me into doing an induction”.(P10)

Yet another form of violation of sexual and reproductive rights emerges in this study, and the existence of xenophobia and racism in these women’s statements is undeniable, promoting exclusion and violence. In a historical continuum, the prejudice and stereotypes exposed only reinforce the ideas that the NHS, through its professionals, has about the bodies of racialised Brazilian women. With negative and disapproving comments about their customs and ways of leading their lives, these women were inappropriately named, causing them to face yet another discriminatory action against them.

“The treatment and access were very different between Portuguese and non-Portuguese women”.(P2)

“There are a lot of obese pregnant Brazilians because they eat a lot of carbohydrates, you eat rice with potatoes mixed in (…)”.(P3)

”Here comes Dr X with another Brazilian here (…)”.(P7)

The same happened with the racism revealed in the testimonies, which ended up being reflected in the development of this event, referring to the eugenicist idea, with the defence that racialised bodies are structurally different. As can be seen, these actions ended up promoting greater vulnerability, making their access to health more precarious. It is possible to perceive the representation of passivity that leads to the neglect that dehumanises these women.

Skin colour, social class, a peripheral place of residence, years of schooling, and access to healthcare all contribute directly to the occurrence of OV, with women living on the periphery, who are black, who have low levels of schooling, and who are going through a process of abortion being the most vulnerable to the occurrence of OV. There is also evidence of women’s lack of preparation and information about OV.

“It’s impossible to deal with these savage people”.(P11)

“You know you’re not going to have your daughter, Brazilians, mixed race, all the women there have bad uteruses, because your’ mixed race”.(P11)

This proves that these women have their bodies disciplined by the state differently than White European women. They receive different treatment based on nationality and race. Although equality is guaranteed by the Constitution, the rupture through intersectional action between medical racism and institutional violence interferes in the health and illness processes of this population. It promotes a change through the omission of institutional powers, such as those of the state, in the face of comments and attitudes like these during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period.

With this practice, it is possible to infer that the effects of the construction of the social imaginary created around the racialised population are reproduced in the health services. This only reinforces the erasure of rights, where the absence of the promotion of person-centred healthcare free from gender, race, and nationality bias is evident and naturalised, anchored in sexist, racist, and xenophobic evidence.

3.2.2. Where Is the Dignity of These Women?

Many extremely important rights are affected by the OV suffered by these women. The abuses suffered by the women interviewed show that they were deprived of their rights. As can be seen from the accounts, they were not informed about their rights with the NHS and were faced with reckless attitudes where doctors insisted on using procedures that were not recommended, along with disregard for their wishes and the traumas that injured these women’s dignity.

“I didn’t realise that pregnant women are entitled to a fee waiver. I’ve always paid, a letter has always arrived at my house, and I’ve always paid for everyone”.(P1)

“I have 11 women to give birth to, right? Unfortunately, we can’t wait for each one’s time (…) It’s going to take a while. If you don’t take this induction, you’ll be here all day”.(P3)

“The assistant started reading my birth plan with irony (…)”.(P4)

“I told my obstetrician everything that happened, but she just brushed it off”.(P8)

“I didn’t have the right to choose the maternity hospital”.(P9)

Violence through the violation of rights was also present in the reports, in relation to the ban on the participation of a companion during labour. The right to have a companion of one’s choice has been guaranteed by Law No. 11.108 since 2005 and requires hospitals and maternity hospitals, whether public or private, to allow a companion of the pregnant woman’s choice to support her during labour, delivery, and the immediate postpartum period. The following accounts reflect the institutions’ disregard for this right:

“When we arrived at the hospital, the father was barred at the door”.(P2)

“My husband wasn’t with me the whole time”.(P8)

“I only learnt that my husband could stay with me hours later through another pregnant woman, I wasn’t told anything”.(P12)

Dignity is a spiritual and moral value inherent to the person; it is manifested uniquely in the conscious and responsible self-determination of one’s own life; and it brings with it a claim to respect from other people. But unfortunately, the care offered to these women during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period in the Portuguese NHS has not been able to fulfil the minimum of what is fundamental and necessary to promote the dignity of this population. As can be seen from the accounts, the racialised Brazilian women in this study were faced with limitations on the exercise of their fundamental rights, affecting the esteem that all people deserve as human beings.

There was a clear absence of the right to information, which must be based on informed consent; the right to an appropriate and adequate cure; and the right not to suffer needlessly, in the proportionality of the means to be used, in the differentiation between ineffective and futile therapy—in other words, in the use of rational and advantageous therapy, which does not lead to violent and undignified therapy. Faced with this question, these women expressed their feelings as follows:

“(…) I felt violated from start to finish”.(P6)

“It was difficult, I couldn’t talk about it, because I’d burst into tears. It was terrible”.(P8)

“I was a piece of meat”.(P10)

These women’s rights were not guaranteed, showing that they were treated unequally through discrimination, social injustice, and structural inequalities, and that their dignity was compromised. All of this prevented the full development of these women, limited their opportunities, and violated their fundamental rights, as the study participants realised:

“(…) I don’t think so because, for me, my right is to be treated well”.(P1)

“My rights were completely violated there, I was clearly violated”.(P6)

“My rights weren’t guaranteed. They violated me”.(P10)

“My rights have not been guaranteed. To be guaranteed, we need to be informed about the procedures”.(P12)

This shows the configuration of lack of training, omission of or inability to provide appropriate treatment in the medical service, or even a lack of ability to make decisions to ensure the health and well-being of these women. When these rights are denied and/or limited, women’s dignity is violated.

4. Discussion

This research demonstrates significant relevance for studies on the intersectionality of gender, race, and nationality in relation to OV as a form of GBV and its impact on SRH for the immigrant population, not only in Portugal but across Europe. As reported in the Case Studies on Obstetric Violence: Experience, Analysis, and Responses by the (), there is growing public awareness and concern about this issue, with an established imperative for quality care during pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum care, along with the understanding of OV as a violation of human rights, a form of GBV, and institutional violence.

To understand how women become victims of OV, it is essential to regain control over the biological event of pregnancy and childbirth, which, since the late 19th century, has been medicalised and subordinated to male-dominated practices (). In this process, pregnancy came to be seen as a risk and pathology, normalising medical interventions (; ). The technocratic model mechanises the female body, turning it into an object of control and social surveillance, reaffirming its historical objectification (; ).

In this context, medical knowledge is imposed as the absolute truth, disregarding women’s wishes and autonomy during childbirth. Institutional violence obscures behaviours that constitute OV, allowing professionals to adopt practices that are not based on evidence, causing suffering (; ; ). Racialised Brazilian women, within a society marked by inequalities in gender, race, and nationality, are even more vulnerable to medical supremacy and technocracy (). The discourse of control over their bodies reinforces the idea that they are incapable of giving birth naturally, without medical intervention (; ). In the hospital environment, these women lose their autonomy and self-determination and are encouraged to believe that they are fragile ().

Furthermore, violence manifests through power relations, manipulation of the female body, inadequate communication, and rights violations within healthcare institutions (). Thus, the care provided during maternity reveals how the symbolic construction of the female body is used to justify interventions, perpetuating inequalities and denying women a positive and respectful experience ().

OV reflects the dehumanisation of care for women during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period, disqualifying their knowledge and ignoring their individual needs. This phenomenon mainly affects racialised Brazilian women, who experience traumatic and painful experiences with significant impacts on their mental, sexual, and reproductive health, violating their human rights (; ). The lack of respect for women’s autonomy and dignity is evident, with practices that limit their protagonism in this process. Healthcare professionals, instead of prioritising their needs and rights, perpetuate power relations and neglect (). Thus, maternal care must be more than technical, incorporating social, cultural, and power-related elements in relationships, as demonstrated by ().

For racialised Brazilian women, OV is a form of GBV that is intersected by social markers such as racism, xenophobia, and sexism (; ). These women frequently report neglect, mistreatment, and the expectation of disrespect before receiving care (; ). The naturalisation of violence and the lack of agency among women reflect the persistence of a system that combines human rights abuses and structural inequalities ().

Intersectional discrimination disproportionately affects racialised women, as can be observed in contexts where economic, social, and cultural forces structure systems of subordination. According to (, ), understanding this discrimination requires attention to the dimensions of race, gender, and nationality, which play central roles in perpetuating these inequalities. Authors such as () argue that intersectionality is crucial for analysing issues of reproductive justice and health, highlighting how these markers influence access to information and healthcare services.

OV thus becomes a broad term encompassing inhumane and scientifically unfounded practices carried out during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period. These include denial of care, lack of clear information, and violation of fundamental rights, such as the right to have a companion (). Such practices are manifestations of institutionalised violence that reflect inequalities in gender, race, and nationality, placing racialised women in situations of greater vulnerability (; ).

Racialised Brazilian women have historically been animalised and dehumanised by colonial practices that position them outside the ideals of femininity associated with White European women (). The modern colonial gender system racialises and hierarchies these women, contributing to their devaluation and disqualification. This logic, as described by (), perpetuates abuse and dehumanisation of their bodies, revealing a system that excludes complex subjectivities.

In addition to explicit violence, there is the impact of the social stigma associated with these women, which hinders access to healthcare and amplifies inequalities (; ). This context fuels OR, which, according to (), arises when the patient’s race influences diagnoses, treatments, and medical decisions, resulting in harm. The author describes racism as a practice sanctioned by institutions and the state, making certain groups vulnerable to premature deaths.

OR is a serious threat to the reproductive and obstetric health of Black and racialised women. Discriminatory comments made by healthcare professionals reveal the dehumanisation of “other” bodies and perpetuate violent practices. The intersectional perspective, as outlined by (), is essential for deconstructing these practices and creating effective interventions that ensure the sexual and reproductive rights of racialised women.

Despite advances in the consolidation of reproductive rights in international legal instruments, gender inequality remains deeply ingrained in society (; ). While these instruments have contributed to female emancipation, many challenges persist, including the need for adequate protection of reproductive rights in the context of technological advances, such as assisted reproductive technologies, which still reflect gender and racial inequalities ().

In this context, analysing OV and OR from an intersectional perspective is fundamental. This approach allows for an understanding of how gender, race, and nationality intertwine to perpetuate inequalities and develop mechanisms that promote structural change (, ). Building an inclusive and equitable healthcare system requires the paradigms that sustain discriminatory practices to be deconstructed, allowing all women access to dignified and respectful care, regardless of their origins or social markers (). It would be crucial to propose strategies to combat racism and xenophobia during obstetric care, which require a multifaceted approach involving public policies, changes in the healthcare system, and sensitisation of both healthcare professionals and society at large (; ; ).

Thus, the feminist movement, advocating for the integrity of human rights, has contributed to the understanding of sexual and reproductive rights as encompassing not only a political and civil perspective but also social and economic perspectives that affect the holders of these rights differently, particularly considering the economic, cultural, and social disparities among different groups of women worldwide (). This should also be reinforced with respect to the associations and entities in Portugal. Through their persistent efforts, in both advocating for the recognition of the term OV in the country and engaging in dialogues, studies, and awareness-raising among the population to combat these practices, they demonstrate a discursive coalition in search of consistent and coherent guarantees on the issue (, ; , ; ; , ).

This reflects and confirms the lack of knowledge about SRH, cultural beliefs, and socio-economic status, along with inadequate access to services in this area—factors that put women at greater risk of vulnerability (; ). These factors often distance them from healthcare, sometimes linked to illegal situations, depriving them of their autonomy in making informed decisions about their bodies (). The () further observes that undocumented migrants are particularly vulnerable, as their rights to access sexual health services are often violated and, due to fear of deportation or existing language barriers, they often do not access healthcare services. The WHO also asserts that human rights, including the right to health, must be universal and not limited to the citizens of a country, covering all those who live in it, regardless of their legal status.

Considering all of these issues, it remains crucial in Portugal to deconstruct each of the narratives that continuously and persistently define racialised Brazilian women as occupying inferior and exclusionary roles in contemporary society (; ). This analysis should clarify the meaning of each of these discourses within the political and social context and facilitate a gender analysis that allows for the development of other conceptions based on more equitable relationships ().

To address these challenges, it is crucial to implement public policies that ensure access to essential services, enact laws protecting minority rights, and establish support programmes for vulnerable groups (; ). This should include developing targeted maternal health programmes for immigrants, eliminating legal and administrative barriers that restrict access to care, and allocating adequate resources to provide high-quality services (; ; ).

However, the ongoing crisis in the Portuguese NHS and the recent passing of Bill No. 364/XVI/1ª, influenced by right-wing extremist parties, represent a significant regression in healthcare access for migrants. Under the guise of combating "health tourism”, this measure overlooks evidence indicating that the NHS crisis stems from poor management and systemic deficiencies rather than demand from non-residents. According to (), the rise in the number of healthcare users does not justify claims of overburdening by migrants, instead highlighting administrative inefficiencies.

These restrictions disproportionately affect pregnant immigrant women, who face systemic barriers, discrimination, and stereotyping (; ). The lack of resources in obstetric care, coupled with staff shortages and emergency unit closures, violates the fundamental right to universal healthcare enshrined in the Portuguese Constitution (CRP, Article 64). To address these structural inequalities, inclusive policies must be implemented to ensure equitable access to healthcare, combat discrimination, and uphold sexual and reproductive rights ().

To achieve this goal, the () states that the effective planning and implementation necessary to achieve universal access to sexual and reproductive health services depend on a well-structured healthcare system. This includes establishing robust governance processes and partnerships, especially involving civil society, including women’s groups and other vulnerable and marginalised groups. The creation of political and legislative frameworks can thus be enabled, with multisectoral engagement and coordinated action in other constructive elements, such as integrated healthcare service delivery ().

Although the prioritisation of actions to strengthen health systems for universal health coverage may vary according to the contexts and needs of each country, it should be supported by a commitment to a rights-based approach and the principle of non-discrimination (; ). This commitment to a rights-based approach is particularly relevant for the implementation of sexual and reproductive health services, where unmet needs may persist even in well-structured healthcare systems.

Therefore, discussing SRH for racialised Brazilian women highlights its significant global relevance because it is aligned with the fight for reproductive justice, addressing the multiple forms of oppression that affect women from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds in various countries. Through this study, we can understand the intersections of race, gender, and nationality, and how these layers of discrimination impact the reproductive health and autonomy of these women.

5. Conclusions

Despite progress, the fight for SRH in Portugal still faces significant challenges. Despite being a fundamental part of human rights and based on principles such as freedom, equality, privacy, autonomy, integrity and dignity, the taboo surrounding these rights persists. To ensure that all people develop healthy and safe sexuality and reproduction, these rights must be recognised, respected, promoted, and defended by society. This struggle cannot be dissociated from an intersectional perspective, especially in the context of racialised Brazilian women, guaranteeing safe, consensual, and informed exploration of sexuality and reproductive desire, if present.

Thus, this study has significant global relevance, as it addresses issues of gender-, race-, and nationality-based inequalities in maternal care and sexual and reproductive rights, which transcend borders and affect women in various social and geographical contexts. The implications for reproductive justice are broad and involve the recognition that reproductive rights are fundamental to women’s autonomy and dignity. OR, which has historically affected racialised women, contributes to global disparities in maternal and infant mortality rates, and it is also an obstacle to equal access to quality healthcare.

It is essential to develop viable policy recommendations to combat OV and discrimination in maternal care, with (1) implementation of anti-discrimination legislation; (2) establishment of specific laws; (3) development of culturally sensitive care protocols—e.g., ongoing and specific training, inclusion of diversity in care practices; (4) ensuring universal access to quality obstetric care; (5) support and expansion of humanised and autonomous birth practices; (6) creation of mechanisms for reporting and follow-up; (7) psychosocial and legal support; and (8) encouraging immigrant community participation in the formulation of health policies, as well as anti-racist training and education for healthcare professionals.

Society is moving towards improvements, but there is still a need for significant changes regarding the humanisation of maternal care during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period. Women’s protagonism over their bodies, rights, and the unique moment of childbirth needs to be embraced more effectively by health professionals, with genuine welcome. Women’s active participation in decision-making processes is crucial, as a lack of autonomy can exacerbate suffering, emphasising the importance of respectful care that is centred on women’s needs.