1. Introduction

Increasingly, people are living longer and choosing to age independently at home or in a familiar environment—also known as ageing in place (

United Nations 2023). These shifts require innovative and thoughtful approaches to care—a process that acknowledges the integral role digital media play in our social practises. As we grow older, technology increasingly becomes a companion in our daily lives. Informal caregiving practises are now often shaped and supported by mobile media, which mediate and transform the ways we provide care (

Sala-González et al. 2021). From communication tools like WhatsApp to health monitoring apps such as iOS Health, the role of digital technology in informal caregiving for older adults is not yet fully understood. Care in later life is multifaceted, spanning intergenerational and reciprocal dynamics—older adults may care for grandchildren, while adult children might assist ageing parents experiencing a decline in health. Mobile technologies have become a key element in these intergenerational caregiving relationships (

Cabalquinto 2020). Exploring how older adults use these tools can provide valuable insights into media literacies, as well as the opportunities and challenges posed by technology in caregiving practices. People aged over 65 are among the first to enter later life in a world saturated by digital technology and data. Mobile media, including smartphones, tablets, and wearables, are universal in Australia and worldwide (

Thomas et al. 2023). At the same time, older adults—especially those aged over 75—are amongst the most digitally excluded (

Thomas et al. 2023). Organisations that support people in their later life can provide essential tools and resources in both formal and informal settings. In this paper, we draw on data collected with older adults through playful workshops, so-called playshops, connected to the Australian University of the Third Age (U3A) in Victoria, Australia. We argue that understanding and mapping the digital informal care practices from lived experience perspectives can provide insights into how older adults can age well and potentially even live at home for longer.

Informal care takes many forms and taking an expansive view of informal care allows us to explore the ways in which this care is practised in mundane, everyday ways.

Van Groenou and De Boer (

2016) define informal care as “the unpaid care provided to older and dependent persons by a person with whom they have a social relationship, such as a spouse, parent, child, other relative, neighbour, friend or other non-kin” (p. 271). The existing taxonomies of informal care can under-develop the importance of self-care, social activities and support as a form of informal care. For instance,

Li and Song (

2019) specify that informal care consists of four categories: “(1) routine activities of daily living (e.g., bathing, toileting, and eating); (2) instrumental activities of daily living (e.g., housework, transportation, and managing finances); (3) companionship and emotional support; and (4) medical and nursing tasks” (p. 2). In their review of the formal and informal care literature,

Li and Song (

2019) found that the majority of research into informal care investigates “care-related challenges including health outcomes and work conflicts for informal caregivers… support and services for informal caregivers; and… the relationship between formal and informal care and related governmental policies” (p. 3). This study suggests that the complexity of informal caregiving in later life using technology has been overlooked.

Our focus is on how informal care can be practised between older adults in informal settings, such as in community learning environments, and how technology can play a supportive role in caregiving relationships. Taking a playful approach to informal care means we can highlight how quotidian care enables older adults to build relationships, which are important for wellbeing and building community. Our findings further demonstrate that sharing technological knowledge, supporting digital literacy, and addressing barriers such as mistrust are central to fostering informal care through technology.

We begin this article with an introduction to how we approach care—through feminist Science and Technology Studies frameworks that enable us to explore caregiving practises and their technological complexities. We also highlight how interdependence, supported by digital tools, can allow older adults to experience both independence and mutual support. Through informal learning networks, older adults can create community, build relationships, and share knowledge across different life experiences. These networks can then enable people to feel understood and heard.

After this overview of the care and informal learning literature, we outline our playful, creative methods with older adults. We argue that many older adults wish to reclaim play, especially if they have been in the workforce. This reclamation of play enables us to situate playfulness as a mode of critical enquiry with older adults that ensures we can explore everyday concerns and triumphs with digital media and technology. Finally, in our Analysis Section, we examine the key themes that emerged from the playshops, addressing the uses, barriers and possibilities of technology for informal caregiving. Our findings demonstrate how older adults engage with technology to support caregiving relationships and navigate the challenges and opportunities it presents.

2. Informal Care Through Everyday Digital Practises

A principal characteristic of informal care is that it is practised in mundane, everyday settings. We approach care through the lens of feminist Science and Technology Studies, which takes seriously the fundamental human need to care and be cared for. We draw from feminist care theorists such as

Tronto (

1993,

1998),

Mol et al. (

2010), and

Puig de la Bellacasa (

2011) who take up care as a political and ethical phenomenon, one that raises important questions around power and responsibility.

Tronto’s (

1993) theoretical work on care has highlighted that care work is integral to everything we do, thus de-naturalising care work as practices specific to women, while also acknowledging that women continue to perform the vast majority of formal and informal care. In recent years, care has increasingly become a space for further feminist work particularly in relation to technology. Scholars have articulated how care is a

practice, “an affective state, a material vital doing, and an ethico-political obligation” (

Puig de la Bellacasa 2011, p. 90), that “care seeks to lighten what is heavy, and even if it fails it keeps on trying” (

Mol et al. 2010, p. 8) and emphasise that “local solutions to specific problems” (p. 7) are integral to effective caring practices.

Though care, especially informal care, is essential, feminised, and undervalued (

Arber and Ginn 1990), we take caution not to theoretically flatten care because, as

Martin et al. (

2015) argue, “practices of care are always shot through with asymmetrical power relations” (p. 627). In the context of ageing, this is particularly pertinent because as Gallistl and von

Laufenberg (

2023) argue, systems that reduce ageing down to computational data can decontextualise data from the lived experience of older adults in the name of ‘care’ and subject older people to ageist stereotypes. We seek to interrogate the mundanity of everyday power dynamics as much as everyday caring practices in informal settings.

Scholars such as Baldassar and Wilding have argued the importance of kinning to understand translational digital media practices for distant care (

Baldassar and Wilding 2020, p. 319). As they note in the context of migrant older adults, digital media play an important role in care networks—especially “care at a distance” (

Pols 2012). This phenomenon has required an expansion of Jeanette Pols’s notion of “care at a distance”—originally deployed to define the synergy between technology and face-to-face care in palliative settings (2012). We need to take seriously the mundane informal modes of care in and through digital media.

Previous research has suggested that the nexus of ageing and technology is fraught with unequal power relations, unnecessary interventions, and ageism (

Dalmer et al. 2022;

Peine and Neven 2019). As

Dalmer et al. (

2022) argue, gerontology research has remained largely optimistic about the promises of technological innovation in the lives of older adults, which overlooks the importance of ambivalence and uncertainty that characterises many people’s relations with technology, including older adults. Our research centres on taking a care-full approach (

Sinanan and Hjorth 2018;

Hjorth 2022;

Zakharova and Jarke 2024) to how digital media and technology are deployed in the lives of older adults, which allows us to explore the co-constitution of ageing and technology (

Peine and Neven 2019). In the introduction to their Special Issue on care-full data studies,

Zakharova and Jarke (

2024) emphasise the emotional, relational, and affective dimensions of care in datafied societies and contexts, arguing that community responses to datafication “aim to shift power and care relations” (p. 659–60). A care-full approach to data and technology with older adults foregrounds the affective dimensions of knowledge sharing including humour, everyday practice, and local community initiatives. As we explore below in our analysis, informal care practices are created within and through informal learning and community environments.

3. Interdependence and Care in Informal Settings

Older people are often active in informal learning and care networks. Being socially active in later life through learning activities can be beneficial. Informal learning for older adults has been linked to improved wellbeing, especially in the ‘Third Age’ when many people aged over 65 start to transition away from paid work and into retirement (

James 2017;

MacKean and Abbott-Chapman 2011). Such informal learning networks can be social, which has also been strongly associated with maintaining mental and physical health and wellbeing in later life (

Weziak-Bialowolska et al. 2023).

Weziak-Bialowolska et al. (

2023) found that older adults who participated in mind-stimulating social leisure activities increased their happiness and decreased their risk of loneliness and depression. These findings suggest that a range of informal networks can be very important for older adults to maintain both interdependence and independence.

Experiencing a range of social dynamics, including interdependence and independence, can be important for older adults’ holistic quality of life (

Robertson et al. 2022). In Australia and other anglophone societies, there can be a false binary between dependence and independence in later life that fails to acknowledge the importance of interdependence (

White and Groves 1997). Interdependence “emphasises the reciprocity of interrelationships and encompasses the giving and receiving of assistance and resources, and complex interactions involving individual (economic, social-familial, personal and physical) and community resources” (

White and Groves 1997, p. 85). Interdependence fits with a care-full framework in that it is reciprocal and acknowledges the necessity and fulfilment that can come from caring for someone, the relief and gratitude of being cared for, and gestures towards the affective complexity of being dependent on others.

4. Methods

This research draws on data from a larger project that used ethnographic and creative, playful methods to understand how older adults are ageing in place with and through data and technology. In this paper, we are using data from four so-called “playshops” in Australia. In the first workshop, one of our participants said, “I have worked all my life. I am now retired. I don’t want to work, I want to play”.

In response to this feedback, we reframed our methods as

playshops. The idea of playshops has been explored in various contexts—

Wohlwend and Medina (

2013) examined how writing playshops contribute to creating cultural imaginaries, while

Rauch et al. (

2016) demonstrated the value of applied play theory in fostering creativity, social interaction, innovation, and critical thinking (

Huizinga 1950;

Caillois 1961;

Sutton-Smith 1992;

Salen and Zimmerman 2004;

Flanagan 2009;

Sicart 2014). Originally developed in early childhood education, playshops were designed as a curriculum approach that treats play as a form of literacy, producing cultural narratives and offering a means to rethink cultural settings (

Wohlwend and Medina 2013). While play-based methods can be deployed in a range of settings and contexts, they have been relatively underexplored with older adults (

Burr et al. 2019;

Hjorth et al. 2024). Indeed, older adults have reported that play has “physical, cognitive, emotional, and social benefits” (

Burr et al. 2019, p. 360), and play has been framed as essential for digital literacy (

Sicart 2014), meaning play-based methods can be particularly useful for exploring the diversity of older adults’ lived experiences with digital media and technologies. Playshops create opportunities for participants to engage with “spaces and imaginaries” (

Wohlwend and Medina 2013, p. 199) by encouraging dialogue, creativity, and teamwork. In our experience, framing group discussions as playshops allowed participants to imaginatively reflect on technological changes throughout their lives and playfully envision the future. By centring exploration on play, we prioritised curiosity, collaboration, and experimentation, creating a welcoming space for participants to explore the intersections of technology, data, and ageing.

Building on this foundation, participants were invited to take part in a 3 h in-person playshop via a U3A recruitment call to their members. They were informed that the aim of the project is to investigate how older adults use digital and mobile media to understand how we might age better at home. Respondents were asked to sign a detailed participant information and consent form if they wanted to take part. Selection criteria included participants who self-identified as being over 60 years old, confident in speaking English, and a user of digital media (such as smartphones, tablets, or smartwatches). A total of 52 participants aged between 65 and 90 years consented to attend the playshops held across Victoria, Australia, with 10–15 participants in each playshop (see

Table 1) and about two-thirds of participants being female. The aim of the playshops was to playfully codesign data visualisations that address the key challenges and opportunities for ageing futures.

Our playshops were deliberately interactive and loosely structured. At the beginning, the project team gave a brief overview of the research, explaining key definitions like data, datafication, and smart devices. Participants were then invited to introduce themselves with two words that came to mind when thinking of data and dive into two playful, creative activities:

- (a)

Multisensorial data mapping: Draw/sketch/list all your devices (using stickers, colours, and other arts-based tools). How are they used? How do you feel about them?

- (b)

Postcard prompts of possibilities: Write a postcard to your past, present, and/or future self about data and technology in your home. How has technology changed? What hopes and concerns do you have?

Especially for older people, maps and postcards are evocative and familiar objects, representing an earlier form of mobile media before the advent of mobile phones (

Hjorth 2005). They symbolise travel, home, locality, and connection. As U3A is an organisation dedicated to “lifelong learning”, participants were eager to create environments in which they shared ideas and learned from each other, highlighting the importance of interdependence and mutual respect that can create care-full communal spaces. Maps and postcards were discussed with the entire group and collected at the end for data analysis. Analysing the data involved identifying and grouping common themes in participant responses, while also exploring unique examples, which were then drawn together in playshop summaries.

5. Results

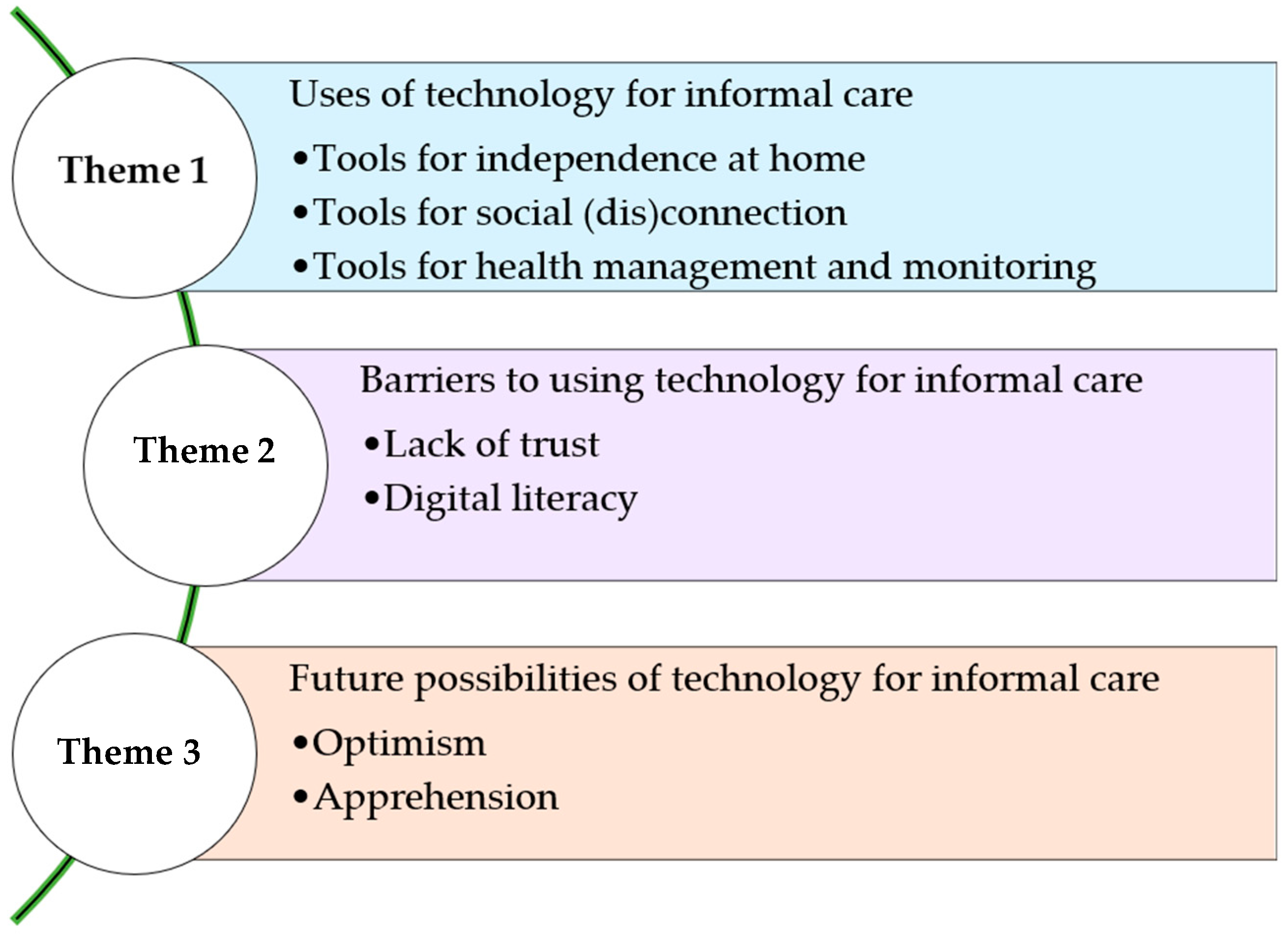

Three themes were identified across the playshops with older adults in regard to informal caregiving and technology, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

5.1. Uses of Technology for Informal Care

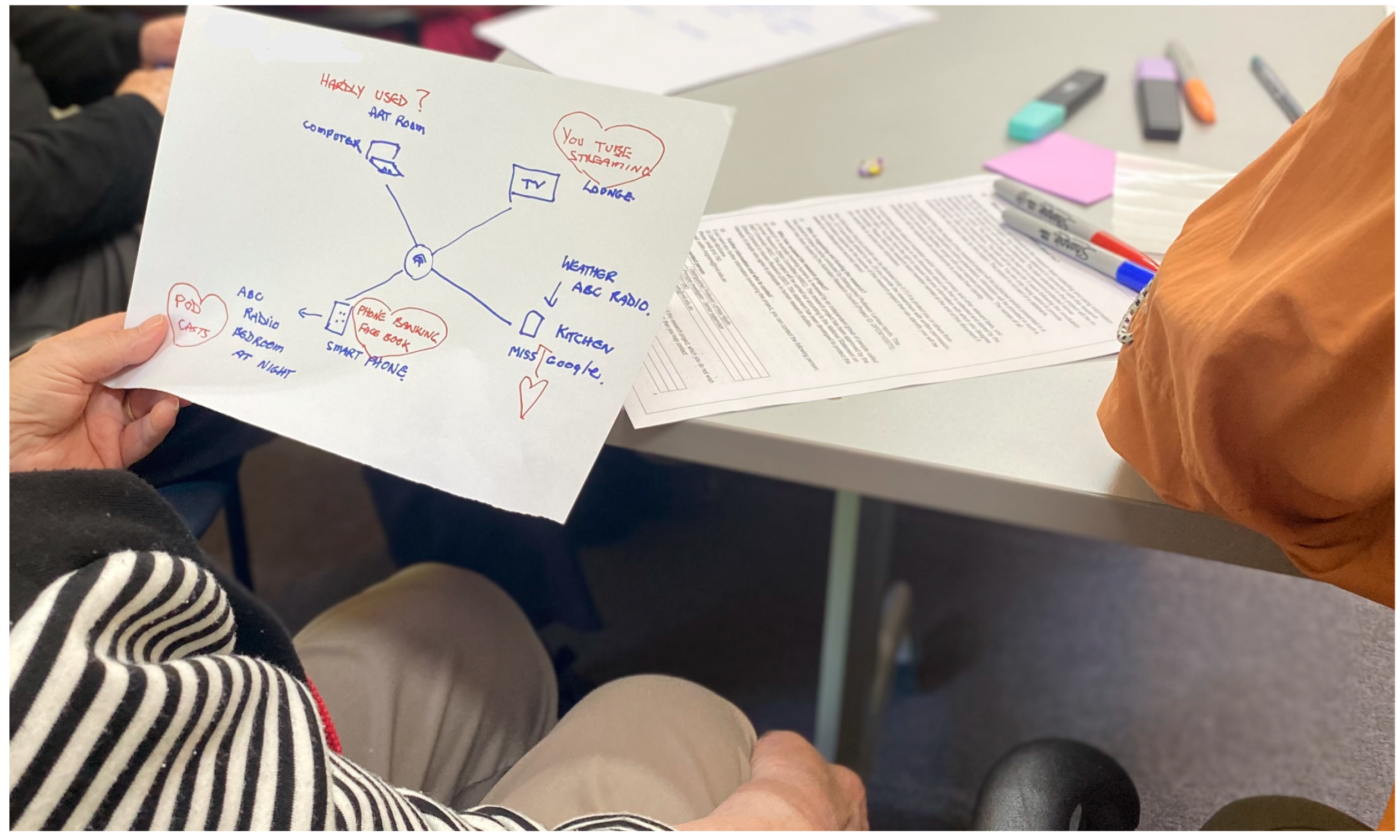

Playshop participants’ maps, postcards, and discussions highlighted the different ways in which older adults used technology to care for themselves and others. Technology was described as a tool for independence at home, for social (dis)connection, and health management/monitoring.

Devices like wearables, smart speakers, and home automation systems were seen as helpful by older adults to maintain independence while living at home. Participants frequently highlighted the potential for technology to reduce the reliance on formal caregiving services. For example, smart home technologies such as voice-activated assistants were appreciated for their role in daily life management, demonstrating how they enable older adults to age in place with minimal external intervention. Silva playfully anthropomorphised her Google smart speaker, saying “

I’ve got Miss Google in the kitchen. She gives me the weather and the ABC Radio. And she also answers me—when I haven’t even asked her a question, she’ll speak”. The love hearts in Silva’s map in

Figure 2 illustrate her positive emotions towards her devices.

Digital tools are seen as a double-edged sword for social interaction. While they enable video calls, social media use, and connection with family, over-reliance on them was perceived as creating risks of social isolation. Balancing technology with meaningful face-to-face interactions was often highlighted in the postcards to participants’ current self. Sandra wrote: “Dear current self, Stay in contact with people, invite them home, go out. Protect your eyes from too much screen time—go into the garden. Enjoy life!” Despite these concerns, using mobile media to speak to family members and stay connected were perceived as some of technology’s most important uses.

Many participants also discussed technology as a tool for health management and monitoring. Medical devices such as wearables, defibrillator implants, and the potential of AI-driven diagnostic tools were recognised as valuable for supporting both self-care and informal caregiving. For instance, one participant mentioned their implant transmitting real-time data to their doctor, reducing the caregiving burden while ensuring that health monitoring remained a priority. These examples demonstrate how technology can play a pivotal role in supporting informal caregiving by enhancing independence at home, facilitating social connections, and enabling effective health management for older adults.

5.2. Barriers to Using Technology for Informal Care

In the playshops, participants also discussed a series of barriers to enjoying and using technology for informal care, including lack of trust and digital literacy.

Participants frequently described a lack of trust in technological systems, corporations, and governments, particularly concerning the handling of personal data and regulation. This mistrust often extended to concerns about scams and fraud, which left participants feeling vulnerable and hesitant to rely on technology for informal care. Fear of being deceived or financially exploited contributed to a reluctance to adopt or engage with digital tools. In the playshops, Helen shared, for example, how she had texted for hours with someone pretending to be her son.

We had a conversation with [someone pretending to be] my son who was in the UK so it was a new phone and [a] new number. We had a conversation for four hours. And then he said, ‘mum, can I have some money?’ so I typed—I smelled a rat—‘What’s the name of your cat?’ and that was the end of it.

Sharing knowledge about how to outsmart scammers constitutes informal caring by allowing older adults to share the affective burden of trying to understand increasingly techno- and datafied societies. By exchanging tips and knowledge, playshop participants not only protected themselves but also contributed to building collective resilience within their communities. Despite these concerns, participants also expressed optimism that trust could be restored through better practices, such as stronger data protections, transparency, and regulations to ensure accountability. Josie summarised this sentiment in her postcard to her future self: “Hopefully all ‘new’ technology is good and we feel we can trust what we will use or be aware of possible danger with some of it”. These discussions underscored the tension between the opportunities that new technologies present and the trust-related barriers that must be addressed to support their adoption in informal caregiving and beyond.

Trust in and use of technology was strongly linked to digital literacy. For many participants, nostalgia for older technologies such as VHS tapes and “dumb” phones was a way to reflect on a perceived loss of simplicity and reliability. Ann fondly described these older devices as “easy to use—once you got it, you got it”. While this nostalgia did not prevent participants from exploring new technologies, it highlighted their frustrations with constant upgrades and rapid changes. Some respondents, like Sandra, even expressed pride in rejecting technology, writing in her postcard to her future self: “You are resisting technology in your home—keep it up!” Perceived intergenerational gaps in technological knowledge made technology adoption difficult for informal care. Many participants discussed challenges with understanding and using new devices. One respondent remarked: “Sometimes it feels like technology is not made for us—it’s too fast, too complex”. This comment illustrates the need for user-friendly interfaces and targeted digital literacy support for older adults so they can use technology to stay connected and care for themselves and others. Peer-led support was essential to acquire this technological knowledge.

The playshops were an ideal setting for intragenerational learning as informal care. Previous research in Australia (e.g.,

Dezuanni et al. 2018,

2019) and around the world (

Ito et al. 2013) has illustrated how informal learning environments with peers can facilitate greater digital knowledge and inclusion. Participants in our playshops demonstrated how knowledge sharing and care are entwined when they discussed how different technologies worked or offered suggestions based on lived experience for how technologies in the home could be better configured for convenience. In one playshop, participant Esther had been given Bluetooth headphones by her son but was confused about how this technology worked. This prompted another participant, Maria, to agree by saying, “

I just don’t understand how Bluetooth actually works [or] where it comes from”. Another participant, Chris, who was identified by other members as the group’s go-to tech person, then provided a brief explanation of the technology. These instances of informal peer teaching are in and of themselves forms of informal caregiving. The Bluetooth example demonstrates what

Martin et al. (

2015) describe as “the ambivalent rhetorics and practices taken up in [care’s] name” (p. 630). While Chris perhaps did not think of himself as providing care, in offering this technological explanation to Esther and Maria he was “animat[ing] and activat[ing] inquiry and analysis” (

Martin et al. 2015, p. 631). Such inquiry and analysis can be important for older adults to make informed decisions about what technologies and digital media they will use, how and why. These decisions can empower older adults in a context where they may be excluded, which can then make it easier for them to live at home for longer with the help of technology.

5.3. Future Possibility of Technology for Informal Care

In the postcards to their future self and the following discussions, playshop participants shared their visions for future caregiving technologies, which ranged from robot caregivers to automated homes, reflecting a mix of optimism and apprehension about technological advancements. A playful suggestion was a riff on the topic of “driverless cars to enable longevity of independence” where another participant quipped “

What about driverless wheelchairs?” for older people in the future. This shows how automation in the future could support independence for older adults as part of informal caregiving. Similarly optimistic, Jessica wrote a postcard to her daughter in the future:

Dear Daughter,

My robot gave me a delightful bath today. She hooked me into my comfortable robotic chair in lovely clean clothes then she heated up my lunch, which I ordered with my voice online. I am having several ‘Facetime’ chats with the grandchildren, I hope you are coping with the changes in your household.

Love, Grandma

This positive outlook on the technological future was often balanced with apprehension about over-automation and loss of control, as shown in this poem-like response by a playshop participant:

Expensive, high maintenance,

Automation of home’s lighting, security, climate, appliances, food preparation, cleaning

Humans will be redundant so why live?

Machines controlling everything.

Who controls the machines?

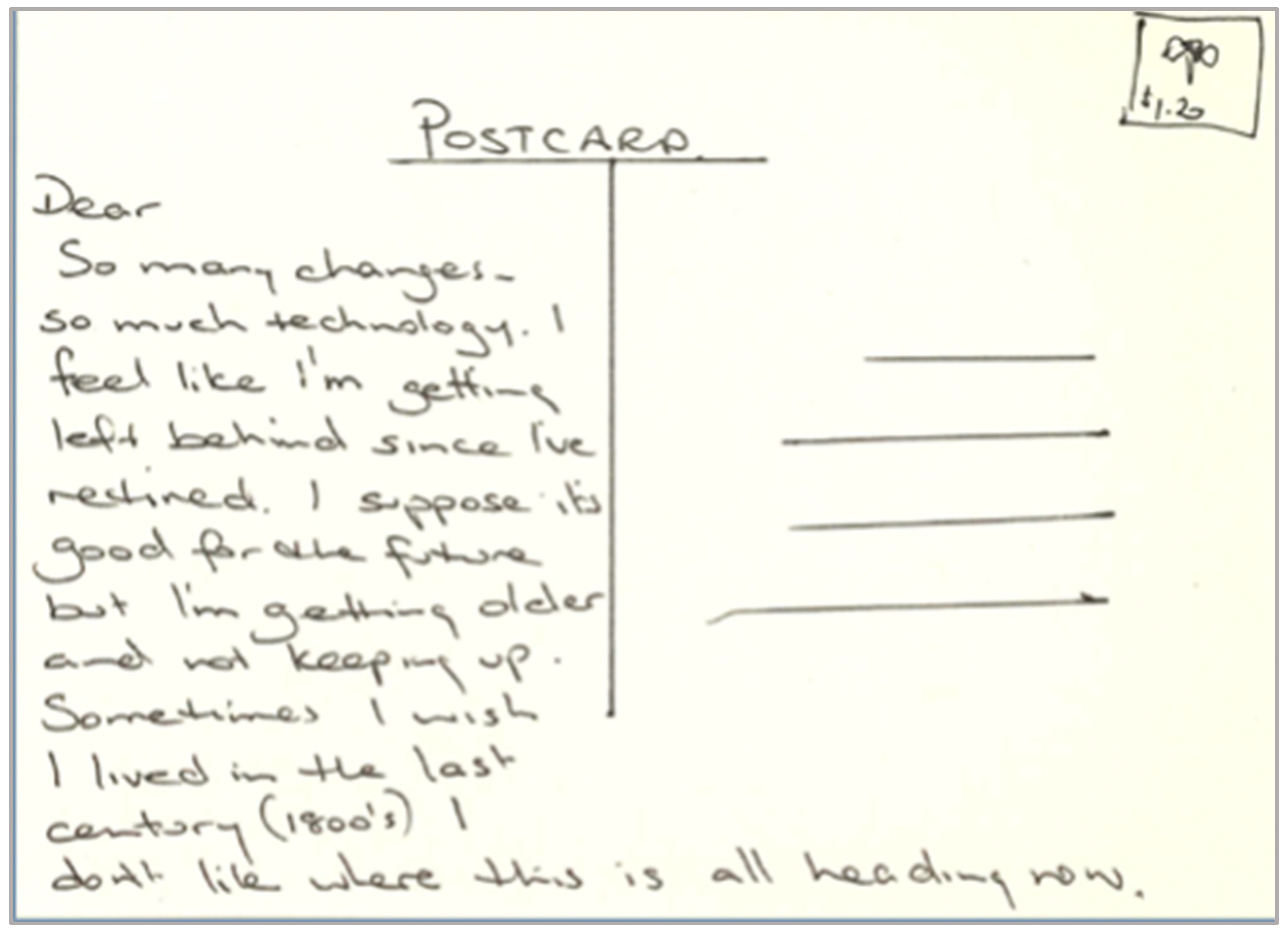

This links to the theme of trust and underscores participants’ broader concerns about the risks of over-reliance on technology in caregiving. Many described the challenges of keeping up with technology as well as uncertainty about future developments, as shown in Ina’s postcard to her present self (

Figure 3).

Participants’ discussions about trust, control, and the need for human involvement suggest that designing technologies that prioritise user needs, transparency, and reliability could help mitigate apprehensions and ensure that automation complements caregiving rather than creating new challenges. These considerations reflect the complexity of integrating technology into informal care while maintaining its human-centric essence.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates how informal digital care intersects with informal learning and play, highlighting the significance of lived experience to ensure informal caregivers are recognised for their important contributions. The findings reveal that technology plays a pivotal role in enabling informal caregiving, from supporting independence at home with smart devices to fostering social connections and facilitating health monitoring. Informal care practices make it possible for older adults to live at home for longer, but these practices are not always recognised or adequately valued. While care requires judgements, navigating power relations and complex processes, “good caring practices” can ensure “people are better able to live in the world” (

Tronto 1998, p. 18). Our findings also highlight the dual nature of technology—while it can enhance caregiving, barriers such as trust and digital literacy must be addressed to ensure its effective use. Our participants have demonstrated caring practices through sharing knowledge, storytelling, and advocacy. The United Nations has argued that “countries should pursue a more equitable, person-centred approach” (

United Nations 2023, p. 113) to the long-term care of older adults, highlighting the need for a better understanding of how informal care is practised in mundane, everyday contexts.

Through our playshops, we have shown how older adults are practising intragenerational and interdependent informal care while digital media and technology is increasingly imbricated into everyday life. Participants shared how digital tools such as wearables, smart speakers, and home automation systems allowed them to age in place, while peer-led support and shared knowledge helped build digital literacy and resilience against challenges like scams. As our findings demonstrate, older adults are creating opportunities to practice informal care by sharing knowledge about how to outsmart scams, informally learning about technology and advocating for carers. These practices are an essential, but often overlooked part of everyday informal care.

In this paper, we have argued that informal digital care practices may have the potential to enable older adults to age in place and live at home for longer. By sharing examples of how participants engaged with technology for independence, social connection, and health monitoring, we have shown how informal caregiving can be enhanced through the thoughtful use of technology. The playful nature of our data collection enabled us to achieve two outcomes: first, to collaboratively facilitate environments where participants could share their experiences and knowledge, and second, to capture older adults’ tacit feelings and practises around informal caring with and through technology. The collaborative nature of our research privileges lived experience while also creating accountability and transparency between us and our participants. This trust-building dynamic is essential in approaching care as a mutual responsibility embedded in everything we do (

Tronto 1993).

Future research into informal digital care with older adults should recognise the importance of trust and mutuality, which can be carefully achieved through creative methods. Addressing barriers such as digital literacy and mistrust of technology should also be a priority for future studies to maximise the potential of digital tools for informal caregiving. Deploying creative methods enabled us to elicit an understanding into lived experience, which can then be applied to different contexts to create better caring infrastructures and systems. As governments and non-governmental organisations continue to look for ways to make later life better, easier, and more accessible, older adults’ expertise around informal learning and community environments is essential to informing policies and practices affecting them.

The generalisability of this study may be confined by the limited cultural diversity in the sample. Future research should therefore investigate how technologies for health management and independence at home can be further tailored to meet the needs of diverse older adults. As we have argued throughout this paper, older adults’ lived experience and everyday practises need to be at the centre of research that may result in decisions being made about the lives of older adults to ensure caring is practised effectively and ethically.