1. Introduction

A seismic shift in the Netherlands’ electoral landscape was observed on 22 November 2023. In the general parliamentary election, Geert Wilders, leader of the far-right Freedom Party (PVV), known for his anti-Islamic incendiary rhetoric and immigration restrictions, secured a significant victory. The PVV won 37 of the 150 seats in the Dutch Tweede Kamer (Parliament), an increase of 20 seats from its previous performance in the 2021 national elections. The clear frontrunner emphasized his electorate’s desire for change in Trumpian style: “

We are going to ensure that the Dutch comes first again”.

1 To fulfil his commitment, he advocated for policies such as the prohibition of mosques, the Quran, and Islamic educational institutions. The PVV’s triumph extended nationwide, with significant implications evident even within the liberal enclave of Amsterdam, where Wilders nearly doubled his electoral gains, capturing 9.9% of the votes (

Onderzoek en Statistiek Gemeente Amsterdam 2023).

Effectively navigating the cultural, ethnic, and religious diversity within the city is one of the primary challenges faced by political leaders in Amsterdam. In recent years, the leadership of policymakers in the city has been insufficient. It has neglected to acknowledge Islam as a growing religion and failed to effectively address the rise of fundamentalist beliefs among young adults (Generation Z, 18–25 years old and Generation Y, 26–35 years old). On 2 November 2004, its foundation was shaken. Amsterdam’s image as a city that embodies an ethos of relaxed tolerance became immersed in a climate marked by tension and anger. The catalyst for this shift was the tragic assassination of filmmaker and atheist Theo van Gogh by a Dutch-born 26-year-old Moroccan Muslim extremist. Van Gogh was well known for his critiques of Islam and multiculturalism. The murder of Van Gogh and the assassination of anti-Islam populist Pim Fortuyn two years prior by a Dutch left-wing extremist precipitated a gradual dismantling of the Dutch tradition of moderation and self-imposed restraint concerning discussions on race and religion (

Eyerman 2011). Persisting tensions between Muslim and Dutch communities have recently intensified, catalyzed by the Hamas-initiated deadly attack on Israel on 7 October 2023, and following the war in Gaza, which claimed the lives of over 30,000 Palestinians. Support for Palestinians and frustration with the Israeli government have been bolstered by protest marches in the city, debates in cultural and educational institutions, and online activism that fosters solidarity with Palestinians.

The target respondents of this study, Gen Y (aged 26–35) and Z (aged 18–25) either experienced their childhood or adolescence during the Van Gogh and Fortuyn assassinations. Currently, in Amsterdam, 123,243 individuals belong to Gen Z and 204,644 belong to Gen Y. Approximately half of these individuals have a non-Western migration background (

Onderzoek en Statistiek Gemeente Amsterdam 2023). Given the increasing influence of far-right PVV in both national and municipal governments, endeavors by far-right extremists to normalize their extremist ideologies and strengthen “white race” normativity, mobilizing effect of the war in Gaza and Quran desecrations in the country (

NCTV 2023), and enhanced broad media endorsement of PVV’s right wing rhetoric (

De Jonge and Gaufman 2022;

Missier 2022a), the demographic composition of Amsterdam remains a crucial factor in understanding the growing potential for multi-ethnic polarization. As a result, extremist ideologies may intensify, increasing the likelihood of unlawful and violent actions directed toward immigrants or marginalized groups (

Van de Bos 2023, p. 125). This may also provoke counterviolence from minority groups among Gen Y and Z, as the tendency to engage in violent offenses appears to be heightened among younger individuals (

Horgan 2024), and even enhanced by online affective content, as the previously mentioned generations seek to find purpose and significance in their lives in digital media ecology (

Missier 2022b).

In general, affective content plays a crucial role in expanding the reach and influence of social media posts by engaging users’ emotions, especially among young adults. (

Duffett 2017). Religious affective content in this inquiry encompasses mediated epistemic sources such as videos, articles, images, and social media posts, designed to inspire, evoke emotions, or cultivate a sense of connection among members of religious communities. Examples are, sacred texts, images of Hindu Gods, Christian saints, Jesus or a cross, the name of Mohammed in Arabic, the crescent moon and star, national flags of Islamic republics, but also provocative content and disinformation (

Al-Zaman 2021). These common examples of objects charged with affective religious and political emotions are intended to inspire, evoke feelings, enthusiasm and cultivate a sense of belonging among members of religious communities, while simultaneously playing a role in shaping both religious and national identities (

Abdel-Fadil 2019).

Social media influence is examined in terms of indirect mechanisms through which social media shapes religious fundamentalist beliefs. The study looks at how social media exerts influence, not in a simple cause-and-effect way, but through intermediate factors, for example, echo chambers, emotional reinforcement, identity formation, or exposure to selective (extreme) content. It also explores how these mechanisms contribute to the strengthening or normalization of fundamentalist worldview. The presented interview data illustrate these indirect influences, showing how participants describe or experience them in practice.

Overall, this study aims to analyze the social media behavior of tech-savvy young adults from Gen Y and Z who belong to Christian, Muslim, and Hindu communities, and to explore the commonalities, imaginaries, and digital

2 versus analog

3 religious epistemic sources in their daily lives in Amsterdam and the environs in which they live, work, and study. The following theoretical segment aims to delve into various themes, which are elaborated upon in the theoretical section, including social imaginaries, epistemic authority, religious authority, and fundamentalist beliefs that will be investigated throughout the fieldwork, guiding the data collection and analysis processes.

Before addressing the research questions, it is essential to first establish the societal significance of this field study. In the Netherlands, recent discourse on extremism has predominantly been oriented toward: The ethics of fundamentalism (

Peels 2023a,

2024), on right-wing extremism (

Sterkenburg 2021;

Valk et al. 2023); populism (

Van den Broeke and Kunter 2021); and Christian nationalism (

Rietveld 2021). In qualitative research scholars often cantered on Muslims (

De Mare et al. 2019) and radical Islam (

De Graaf 2024). International research on digital religion and young adults (

Moberg et al. 2020), provides comprehensive case studies, including from European countries such as Finland and Poland. However, these inquiries do not delve into the topics of epistemic authority and fundamentalist beliefs in digital media, particularly within politically polarized contexts like the Netherlands. Furthermore, the relationship between Hinduism and fundamentalist beliefs remains an underexplored area in the aforementioned studies. Hence, for this inquiry into affective content and digital religion (

Campbell 2013,

2024) and fundamentalist beliefs, I have formulated the subsequent research questions (RQs):

RQ1: How does affective content in digital media influence young adults in Amsterdam (the Netherlands), representing Hindu, Muslim, and Christian faiths, perceive epistemic authority and construct their social imaginaries?

RQ2: How does affective religious content in digital media contribute to the emergence of radical religious beliefs?

This article is structured as follows: After a brief demographical outline of the city, the fieldwork methodology is explained, which is to be perceived as an emergent design, facilitating the extraction of concepts and theories, and accommodating the integration of novel insights and discoveries during fieldwork. Followed by a demographic analysis and fieldwork findings. The paper concludes with an analysis of the findings by incorporating relevant theories and definitions within the specific Amsterdam context in which they were developed.

2. Amsterdam: Demographical Outline

Let us now shift our focus to the key site of this study: The city of Amsterdam and its surrounding areas, which currently serve as one of the country’s key economic hubs, and has been chosen due to its diverse population and its significance as a global metropolitan center. Travelers often label the city as “liberal” and “divers” owing to its reputation for progressive social attitudes toward soft drugs, vice, LGBTQ+ rights, and a general tolerance toward exogenous cultures, religions, and lifestyles (

Dai et al. 2019). In 2022, the capital city had a population of 902,699 individuals from 65 countries across the globe. Among prominent migrant communities, a significant number traced their heritage to Morocco (78,956), Suriname (62,426), Turkey (46,076), and Indonesia (22,698). Projections suggest that by 2050, the city’s population will surge to 1,092,893, as young people are increasingly attracted to urban areas, and when they start families, they tend to remain in cities or relocate to suburban regions (

Onderzoek en Statistiek Gemeente Amsterdam 2025).

Since the 1970s, growth in the population of Moroccan and Turkish ancestry in Amsterdam has led to (Sunni) Islam serving as a marker for the expansion of Muslim demographics (

Kaal 2011;

Uitermark et al. 2014). Similarly, the influx of Christian immigrants, descendants of enslaved Africans, from the former Dutch colony of Suriname during the 1970s, and Christian Africans in the 1980s, has impacted the population of Christians residing in the city (

Van der Meulen 2009, pp. 163–65). In 2018, Muslim demographics were maintained at approximately 13% and Christians accounted for 15% of the population. Additionally, 1% of Amsterdam’s inhabitants are Buddhist, Hindu, or Jewish. Among religious inhabitants, 23% engaged in weekly religious service gatherings. These records support the mainstream secularization theory that in Western societies, religion is decreasing (

Taylor 2007, pp. 767–68). However, individuals of immigration

4 origin, particularly those with a non-European background, are more likely to identify with a religious group than those with a Dutch background (

CBS 2024b).

4. Fieldwork Methodology

Between September 2023 and March 2024, I conducted fieldwork in Amsterdam and its environs regarding digital religion and the influence of social media content on Gen Y and Z. I conducted 31 qualitative, semi-structured in-depth interviews; five were conducted online and 26 face-to-face in Amsterdam. Participant selection is depicted in

Table 1: religious organizations, lecturers, students, religious student organizations, multicultural student organizations, explanatory lectures on research, Instagram story posts, and WhatsApp. A snowball sampling methodology was applied to reach the target audience, as this is recommended for qualitative and descriptive research, particularly in the case of sensitive inquiries, and a high degree of trust is necessary to initiate contact with the target audience (

Baltar and Brunet 2012). The key variables for the selection were Gen Y or Z, preferably residency in Amsterdam and its environs, religious affiliation (Christian, Hindu, Muslim), enrollment or graduation at Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, Inholland University of Applied Sciences, University of Amsterdam, and Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, tech savvy, and frequent users of social media networks.

The participants (

n = 31) consisted of ten Christians (Protestant, Roman-Catholic, and Ethiopian Orthodox), six individuals with non-Western immigration backgrounds (Philippines, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Ghana), and four White Dutch participants. The group also included ten (Sanatan Dharm) Hindus of Surinamese-Indian origin who were migrants, as they were descendants of indentured laborers (

Hoefte 1998) from colonial British-India. Eleven Muslims (nine Sunnis and two Alawites) with immigrant backgrounds were also interviewed, with their origins traced back to Turkey, Morocco, Iraq, Somalia, Indonesia, and Suriname. Some participants also had a bicultural background (e.g., Nigerian-German Christians, Ghanaian-Jewish-Dutch Christians, and Moroccan-Surinamese Muslims). Individual diversity provides a representative palette of the city’s religious demographic and ethnic composition. The number of participants in this urban study was consistent with sample sizes used in similar international academic research on digital media and young adults (

Moberg et al. 2020, p. 4).

The semi-structured interview format allowed comparability across participants and flexibility in exploring individual experiences in depth. Each interview lasted between 60 and 90 min and was conducted either in person or online, depending on the participant’s preference. The semi-structured interview guide consisted of three main sections: (1) general background and everyday media use; (2) online engagement with religious content and communities; and (3) reflections on how digital media shape participants’ understanding and expression of faith. Within these sections, open-ended questions were used to elicit detailed narratives rather than brief factual answers. A notable observation across all groups was the discussion regarding the use of real names versus pseudonyms on social media platforms such as Instagram and TikTok. Owing to privacy concerns and potential negative interference from other users, some individuals prefer to remain anonymous. The choice between using a real name or pseudonym often depends on the sensitivity of the content being shared.

Table 1 is showing the distribution of male and female participants across different genders and religious groups (Christian, Hindu and Muslim).

5. Coding

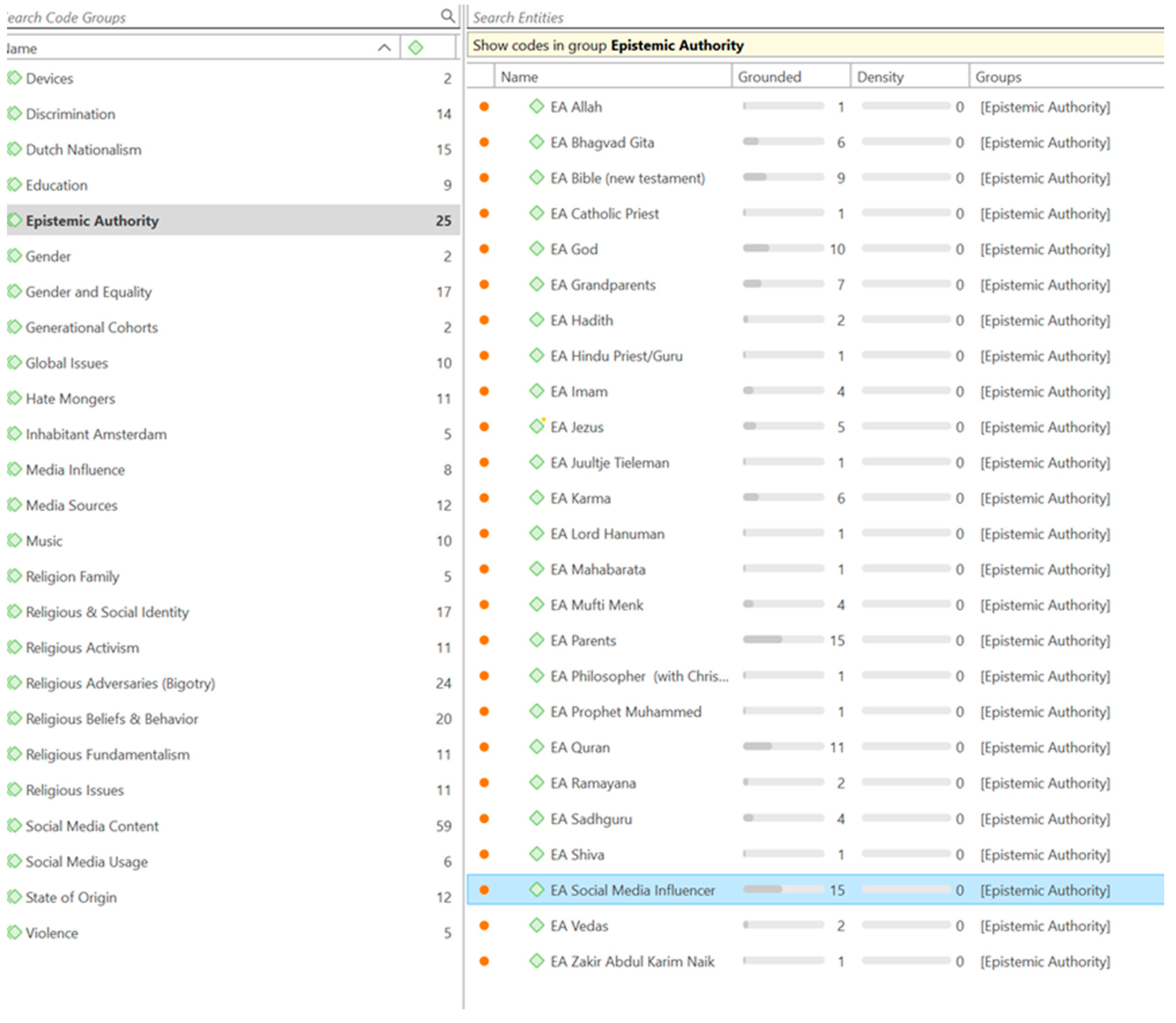

This inquiry is part of a dual project juxtaposing questions, field research, and its methods in Mumbai, India, conducted between November 2022 and January 2023, thereby enabling a comparative analysis of digital religious influence, highlighting perspectives from Gen Y and Z in Mumbai and Amsterdam. The codes (see

Figure 1) used in the Amsterdam study aligned with those from the Mumbai inquiry. However, certain codes were absent in Amsterdam because of cultural or political differences between the two countries. For instance, the involvement of various national influencers and the prohibition of TikTok in India affected the emergence or omission of certain codes. All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and subsequently imported into Atlas.ti software (version 24) for analysis. The coding process began during fieldwork and continued until its completion in March 2024. Atlas.ti was used to facilitate data analysis, enhance the searchability of transcripts and observational reports, streamline code management, and enable the identification of patterns through a combination of code combinations (

Friese 2019, pp. 69–71).

Figure 1 shows a screenshot of qualitative research coding software, displaying different code groups and entities under the category “Epistemic Authority.” On the left panel, various code groups are listed, such as “Devices,” “Discrimination,” “Dutch Nationalism,” and “Epistemic Authority,” with numbers beside them indicating the number of coded references. For example, “Epistemic Authority” has 25 coded references. The right panel focuses on codes within the “Epistemic Authority” group, listing specific entities like “EA Allah,” “EA Bhagvad Gita,” “EA Bible (New Testament),” “EA Catholic Priest,” and more. Each entity has two columns beside it: “Grounded” (the number of times the entity is referenced in the data) and “Density” (a visual bar, though no values are shown in the density column).

Some entities have higher grounded values, such as “EA Parents” and “EA Social Media Influencer,” each with 15 references, while others, like “EA Shiva” and “EA Imam,” have lower values, with 1 or 0 references. All entities are part of the [Epistemic Authority] group.

6. Theoretical Considerations

In this section, I outline several analytical frameworks that will be employed to examine the findings of the field research and to help answer the research questions. We begin by discussing

Pierre Bourdieu’s (

1979) champ du pouvoir (field of power), a renowned sociological theory, to understand how power relations, religious imaginaries, and societal normativity shape respondents’ social lives. Next,

Charles Taylor’s (

2007) framework of social imaginaries was adopted to understand how respondents perceive their roles within social structures and the highly secularized Dutch society. Subsequently,

Linda Zagzebski’s (

2012) argument for epistemic authority was utilized to examine how respondents engage with epistemic and religious authority, as well as epistemic sources, within the context of digital media ecology. Additionally,

Giulia Evolvi’s (

2022,

2024) frameworks of digital religion and hypermediated spaces are incorporated to contextualize how digital environments shape the mediation of faith, belonging, and epistemic legitimacy among minority religious communities. Finally,

Rik Peels’ (

2023a) bicfam definition of fundamentalism was adapted to assess whether respondents exhibit sympathy toward extreme beliefs within their faith.

In his scholarly field theory, Bourdieu suggests that what we consider our “social cosmos” is delineated into a sequence of distinct social microenvironments, referred to as fields. He characterizes fields as social networks with objective structures, sets of beliefs (doxa), and battlegrounds where diverse social actors possessing capital specific to the social field compete for dominance. The hierarchy of the different forms of capital (economic, cultural, social, and symbolic) varies across fields. The specific logic of a given field, including what is at stake and the types of capital required to participate in that field, determines the assets or qualities that shape the relationship between social class and practice. Each class-related asset or quality is valued according to the field’s specific habitus (rules, norms, beliefs, attitudes, and emotions). In this context, Bourdieu refers to symbolic capital, a non-intrinsic value, intangible reputation, or recognition in society that serves as a “meta-capital” to exert influence over other types of power (

Bourdieu 1979, pp. 126–27;

Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992, pp. 66–114).

The analysis demonstrates that the relationship between social classes and practices within a field is shaped by one or a combination of factors that fluctuate depending on the field. Individuals do not move through social spaces merely by coincidence. Their trajectories are influenced by the structural forces inherent to that space, such as objective mechanisms of exclusion and guidance. Individuals resist these forces by asserting their own inertia and utilizing their embodied assets, competencies, objective properties, and titles. However, a certain volume of inherited capital is crucial in the field of power (capital hérité), which must correspond with the set of possible trajectories (faisceau de trajectoires), leading the individual toward certain positions. The transition from one trajectory to another often depends on collective events (war, crises, etc.) or individual events (encounters, connections, protection, etc.), which we tend to describe as coincidences (

Bourdieu 1979, p. 122).

Building on these sociological foundations,

Giulia Evolvi’s (

2022) theory of digital religion introduces the concept of hypermediated religious spaces: The hypermediation theory provides an innovative analytical lens for examining digital religion. In particular, it enables the exploration of religious communities and movements that exist beyond traditional institutional structures and that depend extensively on Internet-based forms of communication. Hypermediation can be conceptualized as both a spatial and relational phenomenon that connects and intertwines online and offline spheres. Rather than merely reproducing physical reality, hypermediated spaces serve to intensify processes of communication and consumption. The “hyper” dimension thus denotes a movement beyond conventional media categories, emphasizing the amplification and multiplication of mediation itself, rendering it increasingly layered, perceptible, and immersive (

Evolvi 2022, p. 74).

Her concept of digital religions illuminates how online platforms serve both as emancipatory spaces of representation and as contested arenas where identity, emotion, and power intersect. By combining Bourdieu’s field theory with Evolvi’s notion of hypermediation, this framework acknowledges that symbolic and digital capital increasingly converge, creating new hierarchies of legitimacy in the digital field of power. Thus, digital media are not neutral arenas of participation; rather, they reproduce and reconfigure symbolic domination, where recognition, visibility, and authority are negotiated through affective engagement and mediated presence. Also, the affective capacity of certain online spaces to evoke strong emotions can give rise to various forms of conflict directed either toward minorities, who are often constructed as the social “other” within Western cultural narratives, or toward secular worldviews. Although expressions of hate may vary in tone and intensity, they frequently involve religious minority communities who perceive themselves as being marginalized. This thereby illustrates

Evolvi’s (

2024, p. 283) argument that the digital media space does not consistently function as safe environment for minority communities.

In recent decades, authors such as

Taylor (

2007) have shifted their focus away from social theory to emphasize how individuals conceptualize their social existence.

5 Taylor refers to the concept of “modern social imaginary,” which describes how ordinary individuals perceive their social existence. This understanding is not framed in theoretical terms but through an imagination anchored in culture and conveyed through images, stories, and legends, reflecting the shared expectations that people have of one another and the collective practices that define what is considered factual and normative in social life (

Taylor 2007, pp. 171–73).

The concept of “modern social imaginaries” also encompasses the ways in which individuals shape and influence the perception and validation of epistemic sources and truths within society, thereby affecting epistemic authority.

Zagzebski (

2012) argues that epistemic authority functions as a framework for understanding the process of knowledge formation through which individuals perceive the epistemic sources that they have received as valid and thus become less dependent on other sources. However, the notion of relying primarily on oneself for knowledge, which is known as epistemic self-reliance, lacks coherence. Therefore, Zagzebski argues that religious authority within a religious community can only be justified if an individual’s conscientious judgement determines that participating in the community and adopting its teachings will support their conscientious self-reflection. When acquiring (religious) knowledge, it is essential to trust an authority or community while exercising careful discernment. This entails evaluating the credibility of those in positions of authority and using conscientious judgements to make assessments (

Zagzebski 2012, p. 203). In the field study, individuals’ conscientious self-reflection on epistemic sources and authority was examined to assess how these evaluative processes are applied to digital media ecology.

In this context, individuals may gravitate online toward epistemic sources with extreme content, hate speech, and fundamentalist versions of beliefs. For this reason, the Rik Peels Bicfam definition of fundamentalism is used in the fieldwork to assess whether the respondents show signs of fundamentalist beliefs:

“A movement is fundamentalist if and only if it is (i) reactionary towards modern developments, (ii) itself modern, and (iii) based on a grand historical narrative. More specifically, a movement is fundamentalist if it exemplifies a large number of the following properties: (i) it is reactionary in its rejection of liberal ethics, science, or technological exploitation; (ii) it is modern in seeking certainty and control, embracing literalism and infallibility about particular scriptures, actively using media and technology, or making universal claims; and (iii) it presents a grand historical narrative in terms of paradise, fall, and redemption, or cosmic dualism”

7. Findings

7.1. Social Media Influence

Across religious traditions, participants described social media as central to their everyday experience of faith, identity, and moral judgment. Digital spaces such as Instagram, TikTok, and WhatsApp emerged as fields of affective power where symbolic capital, digital literacy, and visibility determined one’s influence and authority. In

Bourdieu’s (

1979) terms, these online networks constitute a new “field of power” structured by algorithmic hierarchies rather than traditional forms of economic or cultural capital. As one Muslim female, Gen Z participant, shared, “social media is filled with news and videos that make you angry and sad at the same time; sometimes I scroll and end up crying because of what’s happening to Muslims worldwide.” This affective reaction illustrates the conversion of emotion into symbolic capital, where displays of empathy and moral outrage reinforce social belonging within the digital field.

A Christian male, Gen Y participant, remarked, “the more you like or comment, the more of that kind of content you see. It’s like the app knows what you feel before you do.” This awareness of algorithmic mediation resonates with

Evolvi’s (

2022) notion of “hypermediated religious spaces”, where online and offline realities converge, and

Taylor’s (

2007) idea of social imaginaries shaped by religious and cultural narratives. Within these mediated social media networks, young believers collectively construct social imaginaries that blend religious conviction in the digital media space. For minority communities, such as young Muslims and Hindus in Amsterdam, this aligns with

Evolvi’s (

2024) work on digital minority religions.

Spaces where marginalized believers challenge mainstream narratives through alternative epistemic sources such as

Cestmocro6 on Instagram. Anticipating psychologically distressing social media content regarding the loss of life among co-religionists, Muslim respondents described curating their media consumption by withdrawing from social media and news outlets, a digital environment they widely perceived as hostile. Hindus have reported instances of negative portrayals of their religion in the Netherlands, particularly by the national broadcasting station NOS, as observed during the coverage of the Ram Mandir inauguration in Ayodhya, India. Additionally, they encountered derogatory comments about both Indians and Hinduism on social media platforms such as Instagram, emphasizing the broader issue of misunderstanding and ignorance about Hindu beliefs and practices. Christian respondents emphasized the importance of responsible media reporting and the need for balanced perspectives. This concern reflects a broader call for media outlets to provide nuanced and respectful portrayals of all religious groups to foster mutual understanding and respect. Through digital echo chambers, participants reclaimed symbolic capital and visibility, echoing

Evolvi’s (

2024) claim that online media provide “third spaces” for minority religious agency. In this sense, the findings reveal how digital platforms act as both sites of empowerment and symbolic struggle, echoing Bourdieu’s theory of contested capital within a dynamic social field. Also, data underlines earlier Australian study by

Halafoff et al. (

2021) that young adults actively engage with religious traditions, often outside formal religious settings. This literacy is particularly fostered through social media platforms, which expose youth to a range of religious symbols, rituals, and discourses, frequently tied to mental health, climate activism, and gender identity.

7.2. Epistemic Authority

Participants’ engagement with digital religious figures revealed a reconfiguration of epistemic authority. Influencers such as Mufti Menk,

7 Zakir Naik,

8 Sadhguru,

9 and Juultje Tieleman

10 gained credibility not through institutional standing but through affective resonance and perceived authenticity. As a Muslim female, Gen Z participant, noted, “I love listening to Mufti Menk’s podcasts because he talks about love and marriage in a way that feels real.” Similarly, a Christian female, Gen Z participant, said, “I follow Juultje Tieleman on Instagram; she shows how to live with faith in modern times: “it’s not just about rules but about purpose and meaning in life in our digital age.”

These digital environments expand this epistemic field, producing what

Evolvi (

2022) calls a “hypermediated epistemic ecology”, in which digital capital and emotional affect mediate authority. Participants exercised agency in curating epistemic sources, demonstrating

Taylor’s (

2007) social imaginaries of individualized belief within secular Dutch society. At the same time, this process mirrors Bourdieu’s dynamics of symbolic power: trust and legitimacy are negotiated through reputation, followers, and digital recognition. Consequently, epistemic authority, where individuals trust authorities they perceive as trustworthy and morally reliable (

Zagzebski 2012), becomes more blurry in the interplay between embodied faith and emotional authenticity on social media networks.

While Christianity and Islam share historical roots and a belief in one God, respondents contended with each other over the one true religion. On this matter, Christian and Hindu respondents demonstrated a greater degree of conscientious self-reflection and self-criticism on their sacred texts than Muslims. It is possible that, given the circumstances for some with a migration background, sacred religious texts provide a stronger sense of identity, stability, and support within the Dutch society. Even so, Zagzebski’s notion of conscientious self-reflection becomes essential to prevent dogmatism on individual and communal level, in order to remain open to alternative perspectives within a pluralistic democratic Dutch society.

7.3. Modalities of Fundamentalist Beliefs

Emotionally charged online content occasionally reinforced fundamentalist convictions and polarized worldviews. A Muslim male, Gen Z participant, affirmed, “The Quran already contained the answers before science discovered them; that proves it’s the word of God.” A Christian male, Gen Z participant, argued, “There can only be one true God, it’s irrational to think otherwise.” Meanwhile, a Hindu female, Gen Y participant, stated, “Some Muslim teachings are disturbing to me, like marrying young girls or fighting (Jihad) for redemption in heaven; that’s not peaceful religion, that’s extremism.” These narratives reveal the intersection of affective conviction. The data also indicate that both Christians and Hindus generally view Islam with skepticism, sometimes describing it as a “fanatical religion”. Hindu respondents highlighted difficulties in sustaining friendships with Christians and Muslims, as they perceived a degree of pressure related to religious conversion. Muslim participants exhibited a strong belief in the Quran’s unchangeability and scientific accuracy, viewing it as a source of ultimate truth and unalterable divine law, “long before modern science existed”. This belief system aligns with fundamentalist tenets, emphasizing the superiority of Quranic teachings over other religious scriptures. Participants also expressed concerns about moral and legal issues, advocating stricter punishments in Dutch society.

Drawing on

Peels’ (

2023b) bicfam definition, these tendencies exhibit both modern and reactionary traits, seeking epistemic control through literalism while rejecting liberal pluralism.

Bourdieu’s (

1979) field theory helps explain how religious groups mobilize digital and symbolic capital to defend their epistemic authority within contested spaces.

Evolvi’s (

2024) work on digital minority religions deepens this understanding by showing how online platforms serve as sites of both resistance and radicalization.

Taylor’s (

2007) social imaginaries also illuminate how affective identification with global injustices, such as Gaza cultivates moral solidarity but also entrenches boundaries of belonging. A Christian female, Gen Z participant, reflected, “I feel sadness and anger; I can’t stop thinking about the suffering in Gaza, it makes me question what our leaders stand for.” One Muslim female, Gen Z participant, expressed: “When I see Palestinian children dying, it fills me with pain and anger; I closed my Instagram because it’s too emotional.” In this context, participants’ narratives reveal that their perceptions are profoundly shaped by graphic visual representations of civilian casualties, particularly those featuring women and children.

Among Muslim respondents, the events in Gaza were frequently described as a “genocide”, with many emphasizing that such imagery amplifies affective responses of anger and resentment toward Israelis and, by extension, Jewish communities. Notably, images depicting Israeli soldiers shooting Palestinians appeared to exert a more powerful influence on participants’ social imaginaries than formal historical education about the Holocaust encountered during schooling in Amsterdam. This suggests that the Palestinian–Israeli conflict, as experienced through digital visual culture, is not confined to questions of territory or geopolitics but is also embedded in broader affective, political, and religious frameworks of meaning.

The findings of this study also align with prior research highlighting the intersections between fundamentalist and conspiratorial worldviews (

Van Prooijen and Douglas 2018). Across religious groups, participants expressed varying degrees of receptivity to conspiracy narratives, with Muslim and Hindu respondents appearing somewhat more inclined toward such interpretations. Among Muslim participants in particular, global political events, such as the 9/11 attacks, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the Palestinian–Israeli conflict, were frequently framed within broader narratives of Western and Zionist agendas aimed at undermining Muslim societies. References to powerful financial and media actors, including institutional investor Blackrock and the so-called secret Illuminati organization, further illustrate how these conspiratorial frameworks intertwine perceptions of religion, geopolitics, and injustice. Yet, respondents also acknowledged the social risks of voicing such beliefs, reflecting broader patterns of marginalization and distrust observed in recent scholarship (

Van de Bos 2023). Overall, these findings suggest that conspiracy thinking functions not merely as misinformation, but as a moral and affective response to experiences of perceived inequality in Dutch society and geopolitical power imbalance.

7.4. Discrimination, National Identity, and Media Polarization

Respondents’ narratives about discrimination and national belonging reflected the interplay of power, identity, and mediated representation. A Muslim female, Gen Z participant, stated, “Wilders’s comments make me afraid for our future in this country; it feels like being Muslim is something to hide.” With the exception of the interviewed white Christians, most respondents reported significant experiences of discrimination in Amsterdam and the Netherlands, in the workplace, educational setting, and broader society, primarily based on their ethnic backgrounds or religious affiliations. However, discrimination is not solely attributable to white individuals in Amsterdam. For example, a Christian Gen Z female participant with a migrant background and lesbian identity mentioned experiencing discrimination, particularly from “North African men”, which she attributed more to her sexual orientation than to her religion. This illustrates

Bourdieu’s (

1979) symbolic violence, where dominant discourses impose stigmatizing categories upon minority communities.

White Chistian individuals exhibited a stronger belief in Dutch nationalism, embedded in Christian moral values. They noted profound normative changes in the Dutch cultural landscape as a result of immigration, such as diminishing social cohesion due to increasing religious diversity. They also articulated more skeptical attitudes toward atheists, whom they perceive as dominating public debates. This latter finding echoes recent research suggesting that “stronger individual beliefs in Christian nationalism was tied to more negative views toward atheists” (

Nie 2024, pp. 113–14). In general, data show that respondents attachment to Dutch nationalism can vary, allowing both identification and indifference to exist together.

Respondents also suggested that a significant proportion of online aggression originates from young people seeking sensation and conflict. This behavior is attributed to a variety of factors, including feelings of oppression and the pursuit of a dopamine rush. Online hate highlights the broader issue of online radicalization and the role of digital platforms in facilitating hate speech. In this hypermediated context, as

Evolvi (

2022) emphasizes, online religion transcends mere communication, it becomes a material, affective space in which identity and belonging are continuously negotiated.

8. Conclusions

The findings collectively illustrate how affective digital engagement shapes epistemic authority, social imaginaries, and moral worldviews among young believers in Amsterdam. Synthesizing the frameworks of Bourdieu, Taylor, Zagzebski, Evolvi, and Peels provides a multidimensional lens on this phenomenon. In Bourdieu’s terms, social media represents a digital field of power where symbolic and digital capital define legitimacy. Taylor’s social imaginaries explain how young adults construct moral and religious meaning through shared narratives in the digital media space. Zagzebski’s epistemic authority framework clarifies how individuals navigate trust and autonomy in evaluating religious knowledge both online and offline. Evolvi’s theories of digital religion and hypermediation contextualize these processes as embodied, networked, and emotionally charged practices that blur boundaries between online and offline faith. Also, Hindu and Muslim respondents indicated that the social media networks do not consistently function as a safe environment for religious minorities in the city. Finally, Peels’ bicfam definition of fundamentalism helps identify how the search for epistemic certainty within this mediated field can yield both religious community cohesion and (extreme) exclusionary ideology.

Individuals encounter what

Taylor (

2007, p. 548) describes as “cross-pressured” between their faith and secularists who promote liberal values while perceiving religion as a threat, despite not consistently adhering to those liberal values themselves. This sense of injustice is not a recent phenomenon among immigrant communities: In The Vertigo of Late Modernity,

Jock Young (

2007, p. 167) noted that second-generation Muslim immigrants (from Bangladesh and Pakistan) in the UK are in “a process of being alienated” as a result of experiencing that the white majority is continually undermining its own propagated liberal values in daily life in schools, interactions with a biased police force and a hostile white working environment. However, findings of this inquiry also suggest that researched religious groups do not consistently share identical dimensions of religious habitus, making juxtaposing one against the other complex in the larger Dutch cultural and social contexts.

Subsequently, as individuals’ religions are only marked as a threat, the risk of radicalization may emerge, as some become more susceptible to adopting fundamentalist beliefs. Thus, the findings of this inquiry challenge Amsterdam’s perception of being a tolerant city for ethnic and religious minorities. Apparently, the present governmental policies do not inherently ensure tolerance or authentic respect for diversity and pluralism. In parallel, this research suggests that religion holds greater significance for the youth of this generation compared to previous generations of the Amsterdam citizens. In the recent past, religion played a less prominent role for residents, given the secularization, deconfessionalization and depillarization (

Dekker and Ester 1994, pp. 325–41) in the sixties and seventies in the Netherlands. The expressed attitudes toward other religions and grievances by the young adults in Amsterdam in this study never happens in a vacuum and though Amsterdam has historically been a haven for secularists, free spirits and religious minorities, it raises the question of whether this remains true today, as well as how this may evolve in the future.

Findings also reveal that affective media engagement democratizes access to religious expression while simultaneously reinforcing hierarchies of visibility, authority, and belonging. Digital religion thus emerges not as an abstract or disembodied construct but as a lived, symbolic power, epistemic trust, and social imaginary, a space where religion and media practices intersect to reshape everyday belief and belonging in contemporary Amsterdam, often acting as a catalyst for both social cohesion and polarization.

That being said, allow me to close with a positive conclusion of this study. Despite the beforementioned sense of mistrust or suspicion among respondents there are informal epistemic exchanges on religious beliefs between various faiths. Previous studies (

Ellefsen and Sandberg 2024;

Keijsers et al. 2012) show that young people tend to identify more closely with friends than with family, and having friends from different religious backgrounds can enhance social connections with peers. Such connections are positively correlated with resilience and successful social (re)integration.