Pandemic Prevention Information Disclosure on Social Media During a Public Health Crisis: Meaning, Information Quality, and Posting Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Government Information Disclosure on Social Media

2.2. Public Information Needs Expressed via Social Media During a Public Health Crisis

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Data Cleaning

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Distributions of the Types of Meaning

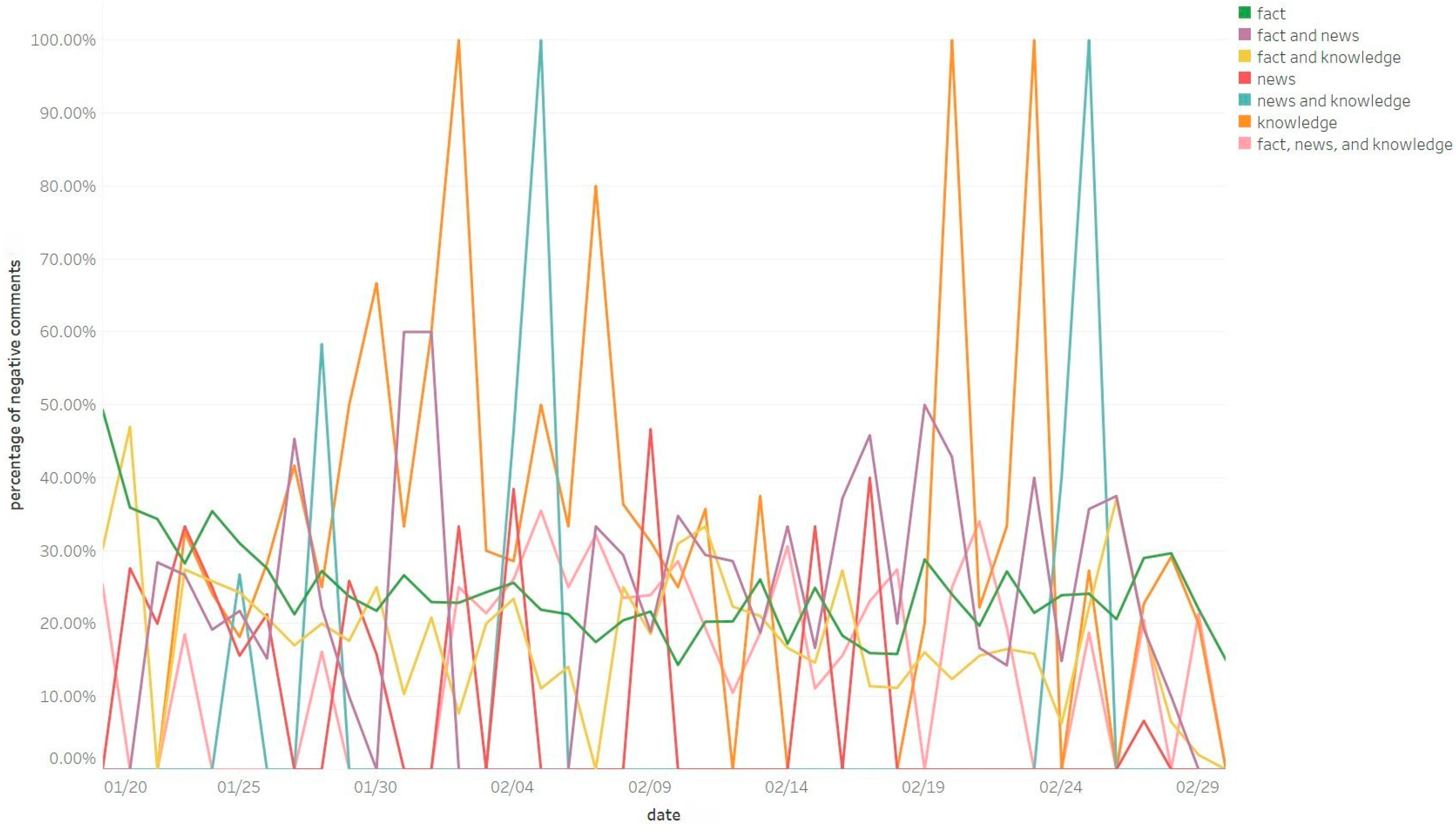

4.2. Distributions of the Topics and Emotions in User Comments

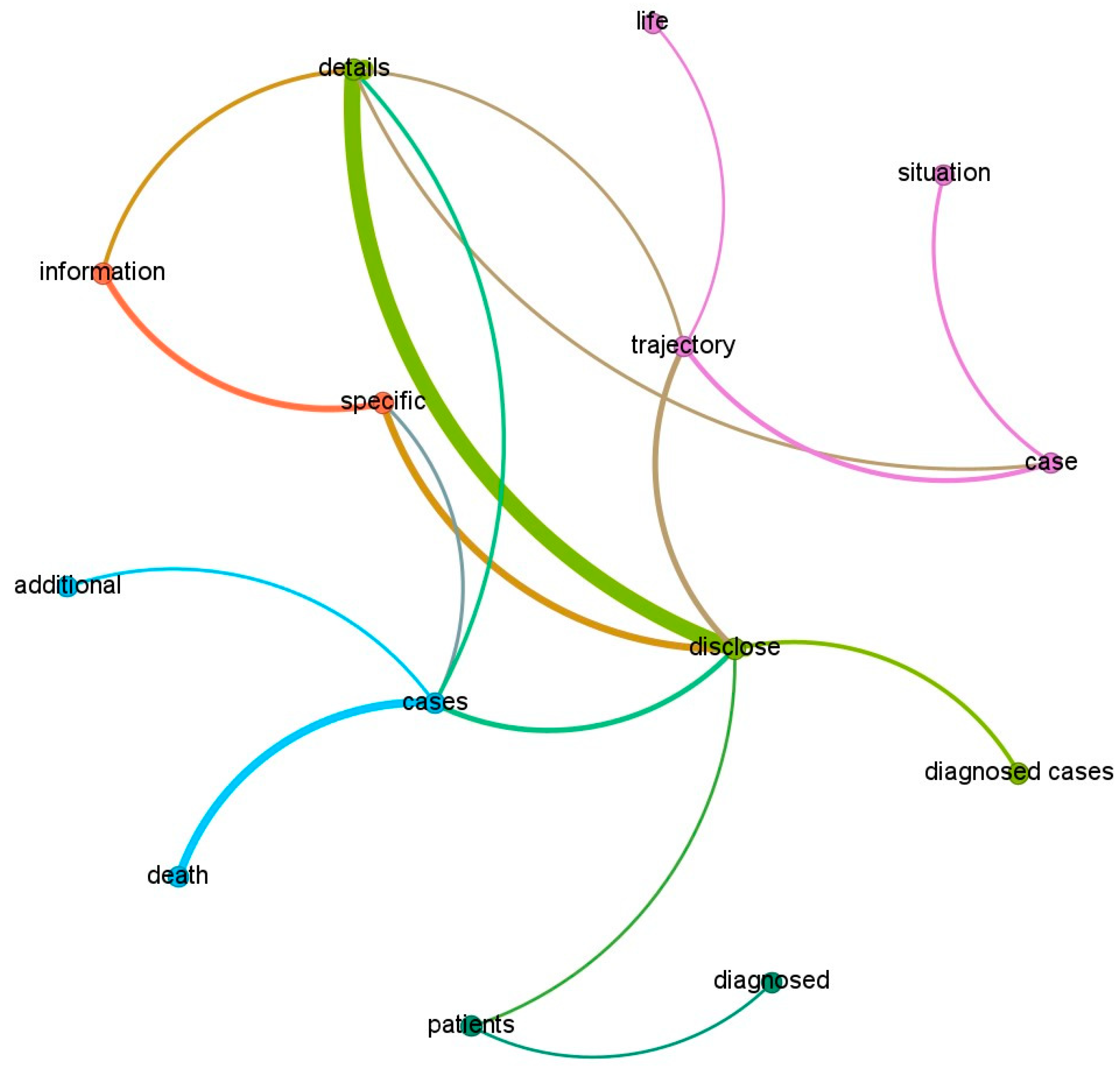

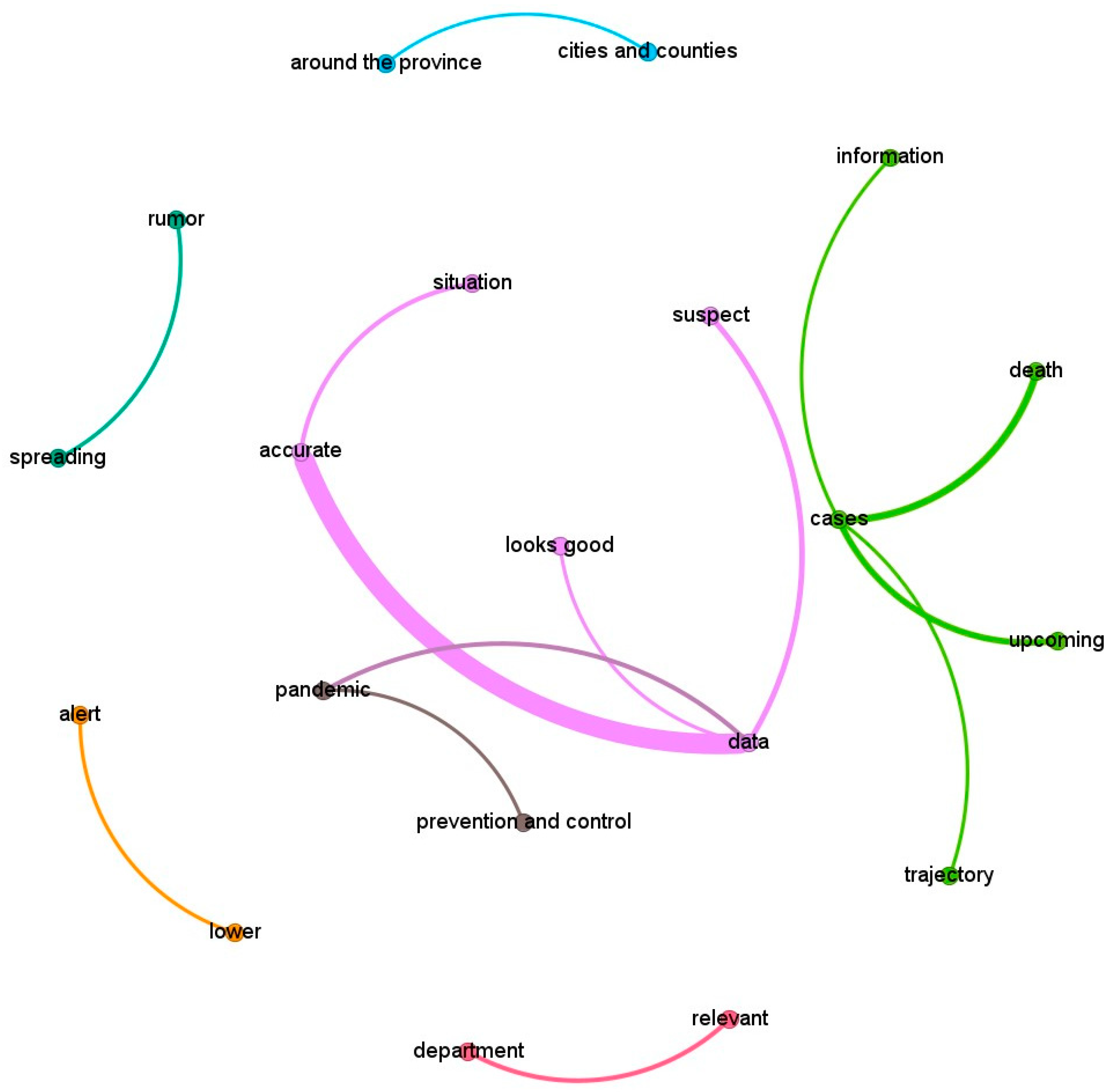

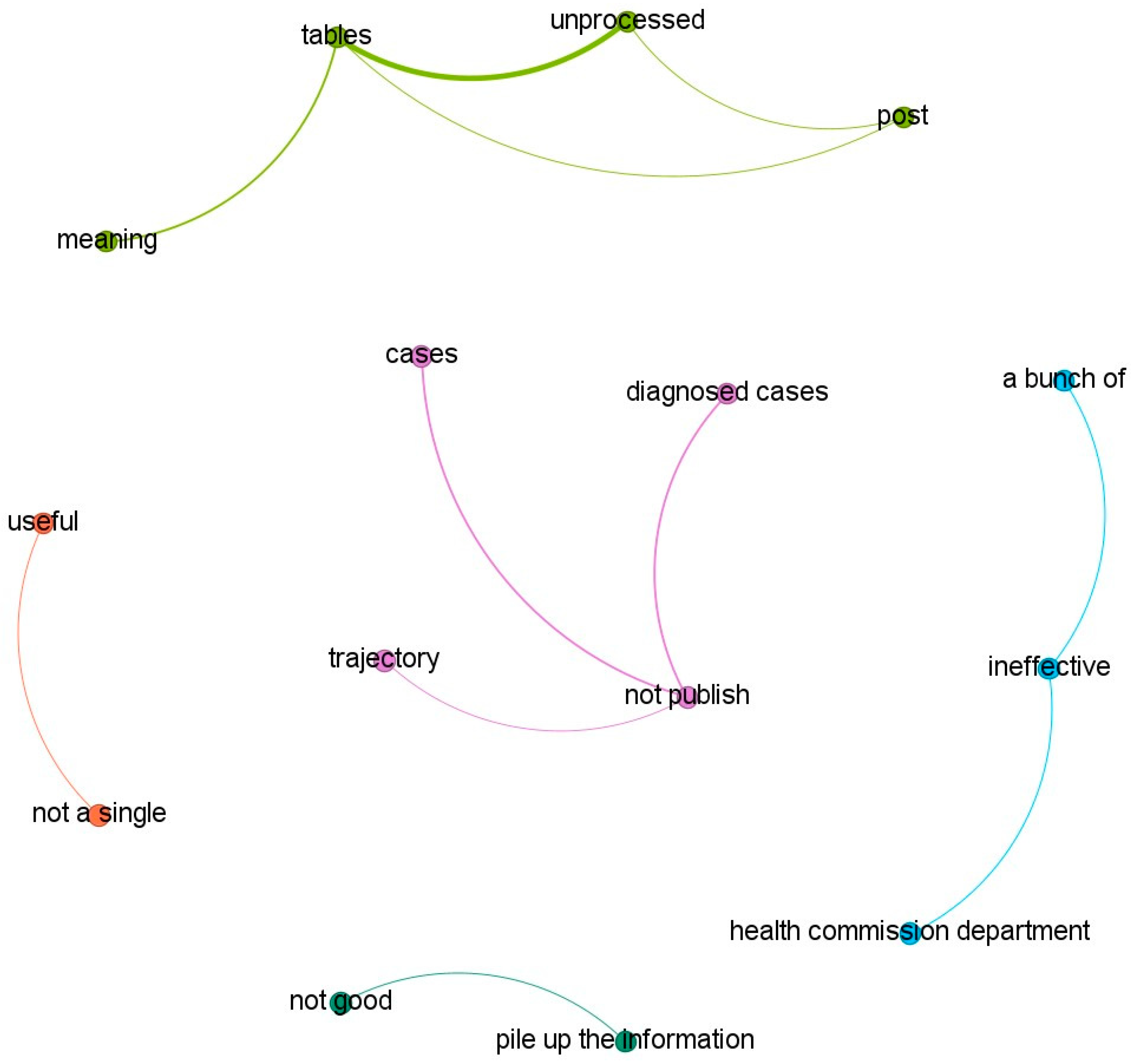

4.3. Public Concerns About Information Quality

5. Discussion

6. Limitations and Future Studies

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| HCDA | Health Commission Department Accounts |

References

- Bakker, Marten H., Cees M. P. van Riel, and Wim van der Weiden. 2019. The interplay between governmental communications and fellow citizens’ reactions via twitter: Experimental results of a theoretical crisis in the Netherlands. Journal of Contingencies Crisis Management 27: 265–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawden, David. 2007. Organised complexity, meaning and understanding: An approach to a unified view of information for information science. Aslib Proceedings 59: 307–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Guangzhong, Ying Zhang, and Qiaofeng Wang. 2021. Analysis of social media data for public emotion on the Wuhan lockdown event during the COVID-19 pandemic. Computer Methods Programs in Biomedicine 212: 106468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, Caleb T., and Rebecca A. Hayes. 2015. Social media: Defining, developing, and divining. Atlantic Journal of Communication 23: 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Qiaofeng, Bing He, and Yong Hu. 2020. Unpacking the black box: How to promote citizen engagement through government social media during the COVID-19 crisis. Computers in Human Behavior 110: 106380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Qiaofeng, Bing He, and Yong Hu. 2021. Why do citizens share COVID-19 fact-checks posted by Chinese government social media accounts? The elaboration likelihood model. International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health 18: 10058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Qiaofeng, Jiaqing Shao, and Huimin Hu. 2023. Dialogic communication on local government social media during the first wave of COVID-19: Evidence from the health commissions of prefecture-level cities in China. Computers in Human Behavior 143: 107715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corinti, Francesca, Daniela Pontillo, and Daniele Giansanti. 2022. COVID-19 and the infodemic: An overview of the role and impact of social media, the evolution of medical knowledge, and emerging problems. Healthcare 10: 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Mingli, Jianchao Cui, and Xudong Guan. 2022. Social media user behavior and emotions during crisis events. International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health 19: 5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, Xinning, Yubo Kou, Kathleen H. Pine, and Yunan Chen. 2017. Managing uncertainty: Using social media for risk assessment during a public health crisis. Paper presented at the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, May 6–11; pp. 4520–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidry, Jeanine P., Yan Jin, Caroline A. Orr, Marcus Messner, and Shana Meganck. 2017. Ebola on Instagram and Twitter: How health organizations address the health crisis in their social media engagement. Public Relations Review 43: 477–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, Loni, Ryan Scharf, Stephen Neely, and Thomas Keller. 2018. Government social media communications during Zika Health Crisis. In 19th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research. Edited by Anneke. Zuiderwijk and Charles. C. Hinnant. New York: Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Xuehua, Juanle Wang, Min Zhang, and Xiaojie Wang. 2020. Using social media to mine and analyze public opinion related to COVID-19 in China. International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health 17: 2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasselström, Anna Elisabeth, and Anders Olof Larsson. 2025. Crisis? What crisis? Assessing over-time public engagement with crisis communication on social media during COVID-19 in Scandinavia. Information, Communication & Society, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Kyoung, and Young Min Baek. 2019. When information from public health officials is untrustworthy: The use of online news, interpersonal networks, and social media during the MERS outbreak in South Korea. Health Communication 34: 991–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, Vikas. 2019. Is it the message or the medium? Relational management during crisis through blogs, Facebook and corporate websites. Global Business Review 20: 743–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Brooke Fisher, and Seon-Ho Kim. 2011. How organizations framed the 2009 H1N1 pandemic via social and traditional media: Implications for US health communicators. Public Relations Review 37: 233–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Haoran, Wei Wang, and Jingyu Zhang. 2023. Better interaction performance attracts more chronic patients? Evidence from an online health platform. Information Processing & Management 60: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Liming, Siqi Duan, Shanshan Shang, and Wenfei Lyu. 2021. Understanding citizen engagement and concerns about the COVID-19 pandemic in China: A thematic analysis of government social media. Aslib Journal of Information Management 73: 865–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, Maggie, Taylor Colangeli, Daniel Gillis, Jennifer McWhirter, and Andrew Papadopoulos. 2021. Examining social media crisis communication during early COVID-19 from public health and news media for quality, content, and corresponding public sentiment. International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health 18: 7986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medaglia, Rony, and Demi Zhu. 2017. Public deliberation on government-managed social media: A study on Weibo users in China. Government Information Quarterly 34: 533–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngai, Cindy Sing Bik, Rita Gill Singh, Wenze Lu, and Alex Chun Koon. 2020. Grappling with the COVID-19 health crisis: Content analysis of communication strategies and their effects on public engagement on social media. Journal of Medical Internet Research 22: e21360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padeiro, Miguel, Beatriz Bueno-Larraz, and Ângela Freitas. 2021. Local governments’ use of social media during the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of Portugal. Government Information Quarterly 38: 101620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, Shilpi, and Sanjukta Das. 2023. Investigating information dissemination and citizen engagement through government social media during the COVID-19 crisis. Online Information Review 47: 316–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, Richard E., and Pablo Briñol. 2011. The elaboration likelihood model. Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology 1: 224–45. [Google Scholar]

- Raamkumar, Aravind Sesagiri, Soon Guan Tan, and Hwee Lin Wee. 2020. Measuring the outreach efforts of public health authorities and the public response on Facebook during the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020: Cross-country comparison. Journal of Medical Internet Research 22: e19334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Tao, Qingkai Kong, Sara K. McBride, Amatullah Sethjiwala, and Qin Lv. 2022. Cross-platform analysis of public responses to the 2019 Ridgecrest earthquake sequence on Twitter and Reddit. Scientific Reports 12: 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savolainen, Reijo. 2011. Judging the quality and credibility of information in Internet discussion forums. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 62: 1243–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Ting, Ping Yu, Brian Yecies, Jiang Ke, and Haiyan Yu. 2025. Social media crisis communication and public engagement during COVID-19 analyzing public health and news media organizations’ tweeting strategies. Scientific Reports 15: 18082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soroya, Saira Hanif, Ali Farooq, Khalid Mahmood, Jouni Isoaho, and Shan-e Zara. 2021. From information seeking to information avoidance: Understanding the health information behavior during a global health crisis. Information Processing & Management 58: 102440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stemler, Steven. 2000. An overview of content analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, Evaluation 7: 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stvilia, Besiki, Michael B. Twidale, and Linda C. Smith. 2007. A framework for information quality assessment. Journal of the American Society for Information Science Technology 58: 1720–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stvilia, Besiki, Michael B. Twidale, and Linda C. Smith. 2008. Information quality work organization in Wikipedia. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 59: 983–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Yixin, Yan Zhang, Jacek Gwizdka, and Ciaran B. Trace. 2019. Consumer evaluation of the quality of online health information: Systematic literature review of relevant criteria and indicators. Journal of Medical Internet Research 21: e12522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syn, Sue Yeon. 2021. Health information communication during a pandemic crisis: Analysis of CDC Facebook Page during COVID-19. Online Information Review 45: 672–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Lei, Wenlin Liu, Benjamin Thomas, Hong Thoai Nga Tran, Wenxue Zou, Xueying Zhang, and Degui Zhi. 2021. Texas public agencies’ tweets and public engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic: Natural language processing approach. JMIR Public Health Surveillance 7: e26720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Linyu, Yujun Yan, and Qinfeng Zhang. 2018. Social media and outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases: A systematic review of literature. American Journal of Infection Control 46: 962–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, Kirsty, Fei Yang, Qiang Yao, and Chaojie Liu. 2023. The role of social media in public health crises caused by infectious disease: A scoping review. BMJ Global Health 8: e013515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China. 2020. Fighting COVID-19 China in Action. Available online: http://english.scio.gov.cn/whitepapers/2020-06/07/content_76135269_5.htm (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Tsao, Shiau-Feng, Helen Chen, Therese Tisseverasinghe, Yang Yang, Lianghua Li, and Zahid A. Butt. 2021. What social media told us in the time of COVID-19: A scoping review. The Lancet Digital Health 3: e175–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Sluis, Frans, Julien Faure, and Sofie Phutachard Homnual. 2024. An empirical exploration of the subjectivity problem of information qualities. Journal of the Association for Information Science Technology 75: 829–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vemprala, Naga, Paras Bhatt, Rohit Valecha, and H. Raghav Rao. 2021. Emotions during the COVID-19 crisis: A health versus economy analysis of public responses. American Behavioral Scientist 65: 1972–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Alice, Rozita Dara, Samira Yousefinaghani, Emily Maier, and Shayan Sharif. 2023. A review of social media data utilization for the prediction of disease outbreaks and understanding public perception. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 7: 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Richard Y., and Diane M. Strong. 1996. Beyond accuracy: What data quality means to data consumers. Journal of Management Information Systems 12: 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yuan, and Chuqing Dong. 2017. Applying social media in crisis communication: A quantitative review of social media-related crisis communication research from 2009 to 2017. International Journal of Crisis Communication 1: 29–37. Available online: https://repository.eduhk.hk/en/publications/applying-social-media-in-crisis-communication-a-quantitative-revi/ (accessed on 30 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Weibo. 2023. The 2023 Annual Report on Government Weibo Influence. Available online: https://n1.sinaimg.cn/finance/a0479a1f/20240131/2023NianDuZhengWuWeiBoYingXiangLiBaoGao.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- White, Marilyn Domas, Sharon L. Smith, and Philip L. Smith. 2006. Content analysis: A flexible methodology. Library Trends 55: 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2020. Managing Epidemics: Key Facts About Major Deadly Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/managing-epidemics-key-facts-about-major-deadly-diseases (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Xu, Jing. 2020. Does the medium matter? A meta-analysis on using social media vs. traditional media in crisis communication. Public Relations Review 46: 101947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Lihong. 2015. Back to the fundamentals again: A redefinition of information and associated LIS concepts following a deductive approach. Journal of Documentation 71: 795–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Lixuan, and Iryna Pentina. 2012. Motivations and usage patterns of Weibo. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 15: 312–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Ting, and Li Yu. 2021. The relationship between government information supply and public information demand in the early stage of COVID-19 in China—An empirical analysis. Healthcare 10: 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Wei, Hui Yuan, Chengyan Zhu, Qiang Chen, and Richard Evans. 2022. Does citizen engagement with government social media accounts differ during the different stages of public health crises? An empirical examination of the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Public Health 10: 807459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yujun, and Sangwon Song. 2020. Older adults’ evaluation of the credibility of online health information. In CHIIR ‘20: Conference on Human Information Interaction and Retrieval. Edited by Heather O’Brien and Luanne Freund. New York: Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 358–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Yong, Sixiang Cheng, Xiaoyan Yu, and Huilan Xu. 2020. Chinese public’s attention to the COVID-19 epidemic on social media: Observational descriptive study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 22: e18825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Ruoxi, and Xiaohua Hu. 2023. The public needs more: The informational and emotional support of public communication amidst the COVID-19 in China. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 84: 103469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Health Commission Microblog | Posts n (%) | Comments n (%) | Average Number of Comments per Post |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Shanghai | 191 (26.68) | 6168 (13.67) | 32 |

| Healthy Tianjin | 105 (14.66) | 1146 (2.54) | 11 |

| Healthy Shandong | 79 (11.03) | 5820 (12.89) | 74 |

| Healthy Beijing | 65 (9.08) | 14,911 (33.04) | 260 |

| Healthy Shanxi | 62 (8.66) | 2691 (5.96) | 43 |

| Healthy Guangdong | 51 (7.13) | 2188 (4.85) | 43 |

| Healthy Sichuan | 50 (6.98) | 3514 (7.79) | 70 |

| The Health Commission of Henan | 40 (5.59) | 4750 (10.52) | 119 |

| The Health Commission of Jilin | 37 (5.17) | 903 (2.00) | 24 |

| Healthy Jiangsu | 36 (5.03) | 3044 (6.74) | 85 |

| Total | 716 | 45,135 | 63 |

| Types of Meaning | Themes | Definitions | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fact | Data collection methods | Data collection time point and frame as well as criteria, and data disclosure time point | From 18:00 to 24:00 on 23 January… |

| Case statistics | Data of new, current, and historical cases that have been confirmed, suspected, or cured, or are deceased | Ten new cases have been reported. | |

| Case profiles | Demographic background, travel history, and disease progression of cases | A 32-year-old female patient was admitted to the hospital for treatment on 21 January. | |

| News | Preventive measures | Preventive regulations and actions | The government has implemented a screening procedure. |

| Medical measures | Medical procedures and actions to diagnose, treat, and follow up confirmed cases | The government has organized an expert panel for consultation and medical care. | |

| Knowledge | Disease control directives | Instructions or suggestions regarding individual activities | We encourage residents to minimize outings and reduce family gatherings. |

| Instructions or suggestions regarding public activities | Enterprises and institutions should minimize group activities and enhance indoor ventilation. |

| Comment Type | Themes | Example Comments |

|---|---|---|

| On meaning | Response to meaning | Take precautions and stay safe during the epidemic. |

| On information quality | Completeness | Which district is it? What’s their travel history? |

| Accuracy | Patient numbers are up, but close contacts haven’t changed. The numbers may be incorrect. | |

| Timeliness | Please update the number. | |

| Usefulness | Information on travel history is more informative than disclosing the number of the cases. | |

| Ease of use | I don’t understand. Does it mean recovered patients have antibodies? | |

| On posting method | Responsiveness | Could you respond to my questions? |

| Regularity | Information is not released on a regular schedule. | |

| Format | Can you post information in the same format every day? |

| Type of Government Posts | Total (%) | Number of Comments | Average Comments Received per Post |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facts | 434 (60.61) | 34,392 | 79 |

| Facts and news | 105 (14.66) | 2336 | 22 |

| Facts and knowledge | 60 (8.38) | 4354 | 73 |

| News | 30 (4.19) | 670 | 22 |

| News and knowledge | 5 (0.70) | 201 | 40 |

| Knowledge | 51 (7.12) | 1024 | 20 |

| Facts, news and knowledge | 31 (4.33) | 2158 | 70 |

| Total | 716 (100) | 45,135 | 63 |

| Types of Comments (%) | Comment Topics | Total n (%) | Positive n (%) | Neutral n (%) | Negative n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| On meaning (74.1) | Response to meaning | 33,451 (74.1) | 4627 (93.3) | 20,335 (70.0) | 8489 (76.9) |

| On information quality (25.5) | Completeness | 6226 (13.8) | 92 (1.9) | 4418 (15.2) | 1716 (15.5) |

| Timeliness | 1316 (2.9) | 43 (0.9) | 945 (3.2) | 328 (3.0) | |

| Accuracy | 1134 (2.5) | 83 (1.7) | 849 (2.9) | 202 (1.8) | |

| Usefulness | 218 (0.5) | 6 (0.1) | 124 (0.4) | 88 (0.8) | |

| Ease of use | 2608 (5.8) | 96 (1.9) | 2348 (8.1) | 164 (1.5) | |

| On posting method (0.4) | Responsiveness | 106 (0.2) | 11 (0.2) | 58 (0.2) | 37 (0.3) |

| Regularity | 45 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | 37 (0.1) | 5 (0.1) | |

| Formats | 31 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) | 13 (0.0) | 17 (0.2) | |

| Total | 45,135 (100) | 4962 (100) | 29,127 (100) | 11,046 (100) | |

| Topic of Government Post | Positive n (%) | Neutral n (%) | Negative n (%) | Total n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facts | 3427 (13.7) | 15,074 (60.3) | 6496 (26.0) | 24,997 (100) |

| Facts and news | 312 (16.5) | 1112 (58.8) | 468 (24.7) | 1892 (100) |

| Facts and knowledge | 613 (17.9) | 2088 (61.0) | 721 (21.1) | 3422 (100) |

| News | 95 (16.4) | 336 (58.2) | 147 (25.4) | 578 (100) |

| News and knowledge | 4 (2.7) | 91 (61.5) | 53 (35.8) | 148 (100) |

| Knowledge | 44 (5.3) | 542 (65.4) | 243 (29.3) | 829 (100) |

| Facts, news and knowledge | 132 (8.3) | 1092 (68.9) | 361 (22.8) | 1585 (100) |

| χ2 | 193.53a | 58.73a | 61.18a | |

| df | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Topics of Comments on Quality | Positive n (%) | Neutral n (%) | Negative n (%) | Total n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completeness | 92 (1.5) | 4418 (70.9) | 1716 (27.6) | 6226 (100) |

| Timeliness | 43 (3.3) | 945 (71.8) | 328 (24.9) | 1316 (100) |

| Accuracy | 83 (7.3) | 849 (74.9) | 202 (17.8) | 1134 (100) |

| Usefulness | 6 (2.8) | 124 (56.8) | 88 (40.4) | 218 (100) |

| Ease of use | 96 (3.7) | 2348 (90.0) | 164 (6.3) | 2608 (100) |

| Topic of Comments on Posting Method | Positive n (%) | Neutral n (%) | Negative n (%) | Total n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responsiveness | 11 (10.4) | 58 (54.7) | 37 (34.9) | 106 (100) |

| Regularity | 3 (6.7) | 37 (82.2) | 5 (11.1) | 45 (100) |

| Format | 1 (3.2) | 13 (41.9) | 17 (54.8) | 31 (100) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Fan, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, T.; Gu, Y. Pandemic Prevention Information Disclosure on Social Media During a Public Health Crisis: Meaning, Information Quality, and Posting Method. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14120681

Zhang Y, Fan S, Li Y, Zhang T, Gu Y. Pandemic Prevention Information Disclosure on Social Media During a Public Health Crisis: Meaning, Information Quality, and Posting Method. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(12):681. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14120681

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yao, Sinuo Fan, Yuelin Li, Tairui Zhang, and Yanan Gu. 2025. "Pandemic Prevention Information Disclosure on Social Media During a Public Health Crisis: Meaning, Information Quality, and Posting Method" Social Sciences 14, no. 12: 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14120681

APA StyleZhang, Y., Fan, S., Li, Y., Zhang, T., & Gu, Y. (2025). Pandemic Prevention Information Disclosure on Social Media During a Public Health Crisis: Meaning, Information Quality, and Posting Method. Social Sciences, 14(12), 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14120681